Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 14

Repairing Charity Trust in Times of Accidental Crisis: The Role of Crisis History and Crisis Response Strategy

Authors Yuan X, Ren Z, Liu Z, Li W, Sun B

Received 28 September 2021

Accepted for publication 3 December 2021

Published 20 December 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 2147—2156

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S341650

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Xuhui Yuan, Zirong Ren, Zhengjie Liu, Weijian Li, Binghai Sun

School of Teacher Education, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, 321004, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Weijian Li; Binghai Sun

College of Teacher Education, Zhejiang Normal University, 688 Yingbin Avenue, Jinhua, 321004, People’s Republic of China

Email [email protected]; [email protected]

Purpose: Since it is practically significant to explore how to repair the public’s trust in charities during accidental crisis, this study explored the crisis response strategies that charitable organizations with and without crisis histories could adopt when facing a current accidental crisis.

Participants and Methods: Study 1 (N = 177) used a 2 × 2 between-subjects design to examine the effects of crisis history (no crisis history vs. crisis history) and crisis response strategies (diminish vs. rebuild) on charity trust repair during an accidental crisis. Study 2 adopting a 3 × 2 between-subjects design examined the effects of crisis history (victim crisis history vs. accidental crisis history vs. preventable crisis history) and crisis response strategies (diminish vs. rebuild) on charity trust repair during an accidental crisis.

Results: The results of Study 1 showed that the diminish strategy adopted by charities in an accidental crisis can enhance public trust. However, if the charity has a crisis history, the rebuild strategy will enhance public trust. The results of Study 2 showed that, under the victim crisis history condition, participants’ charity trust was borderline significantly higher than their pre-test charity trust when the diminish strategy was used. However, rebuild strategies did not significantly increase trust. Under the accidental crisis history condition, diminish strategies improved trust after the accidental crisis, while rebuild strategies did not. Under the preventable crisis history condition, diminish strategies did not improve trust after an accidental crisis, while rebuild strategies did.

Conclusion: Charities should adopt a diminish strategy when experiencing their first accidental crisis. Charities with a victim or accidental crisis history should adopt a diminish strategy when facing a current accidental crisis. However, if a charity has a preventable crisis history, rebuild strategies are the most appropriate response to a current accidental crisis.

Keywords: situational crisis communication theory, SCCT, crisis history, crisis response strategy, trust repair, charity

Introduction

Trust is defined as “a willingness to rely on an exchange partner in whom one has confidence”.1 As an important aspect of the social capital of a charity organization, trust does not only reduce donors’ perceptual risk and uncertainty of donating, but is also key to establishing long-term relationships with donors.2,3 However, crisis events have caused the public to have a negative perception of charity organizations—damaging the trust in organizations, reducing individual donations, and even threatening the survival of such organizations.4–6 After summarizing and expanding the crisis classification used in the literature, Coombs7 obtained a list of 13 crisis classification items and then measured the public’s attribution of responsibility for these crises through experiments. According to the experimental results, these crises were further classified into three categories: victim, accidental, and preventable.7,8 First, victim crisis refers to a crisis wherein both the organization and its stakeholders are victims. As such, organizations are considered to be minimally responsible for victim crisis situations. For example, some netizens fabricated fake news that a charity embezzled charity money, which led to the organization being strongly denounced by netizens. Second, an accidental crisis stems from the unintentional actions of the organization. Thus, persons attribute moderate responsibility to organizations in accidental crises. For example, an organization made an unintentional mistake in transferring money to a patient’s family, who received only part of the money. Third, a preventable crisis is labeled “preventable” because persons believed that the crisis could have been avoided or that the organization intentionally engaged in inappropriate action. For example, a charity illegally purchased inferior materials and donated them to disaster areas. Accidental crises are the most frequent type of crisis, and strategies to respond to such a crisis are the least effective.9,10 Therefore, it is of great practical significance to study how to repair the public’s trust in charity organizations in times of accidental crisis.

The situational crisis communication theory (SCCT) prescribes crisis response strategies for organizations to use post-crisis based on the type of crisis that occurs.11 According to the SCCT, the most appropriate crisis response strategy in an accidental crisis is diminish followed by rebuild strategies. Diminish strategies aim to reduce the negative effects generated by a crisis using excuses (eg, the organization lacked control over the crisis) and rationalization (eg, the crisis was not as detrimental as people were led to believe). Meanwhile, positive rebuild strategies include offering compensation, whether material or symbolic, and offering a full apology.12 The diminish crisis response strategies involve arguing that a crisis is not as bad as the public think or that the organization lacked control over the crisis. An accidental crisis represents an organization’s unintentional behavior. The responsibility assumed by the organization in the diminish strategy matches the responsibility in the accidental crisis, and the negative cognition of stakeholders is minimized.13 Moreover, a full apology (rebuild) in an accidental crisis provides no greater benefit than an excuse strategy (diminish).11 Using overly accommodating strategies when unnecessary actually can worsen the situation, as stakeholders begin to think the crisis must be worse than they thought if the organization is responding so aggressively.14 Sisco10 was the first to experimentally manipulate crisis types and response strategies of charity organizations and provide empirical evidence regarding the SCCT. The results showed that there was no significant difference between the diminish strategy and the rebuild strategy in repairing the organizational image in times of an accidental crisis. The participants in the study attributed the significantly different crisis responsibility scores to the three types of crises. However, crisis responsibility was measured after the participants read about the crisis and the crisis response strategy, and their judgment of crisis responsibility was influenced by the crisis response strategies. Moreover, no checks on the manipulation validity of crisis response strategies were performed in the study. Only with a comprehensive examination of the independent variable can we draw conclusions with higher ecological validity. Therefore, our study involved manipulation checks on crisis types and response strategies in order to explore the most appropriate crisis response strategy for charity organizations in times of an accidental crisis. We first hypothesized the following.

H1: In an accidental crisis, the most appropriate crisis response strategy for charity organizations will be the diminish strategy.

Crisis history refers to a crisis that an organization experienced in the past.7 Under the SCCT, crisis history increases the responsibility attribution and reputational threat of a current crisis.11 An accidental crisis is originally considered a moderate reputational threat that becomes a severe threat when the organization has a history of crises.11 At this time, if charities continue to adopt the diminish strategy, it will cause more doubts and dissatisfaction among the public and further damage their trust. Thus, crises in the accidental cluster should be treated like those in the intentional cluster when there is a crisis history, and an organization should use a rebuild strategy to repair trust.11,15 Roberts9 showed that enterprises with a crisis history can achieve better results by using a rebuild strategy rather than a diminish strategy in times of accidental crisis. However, previous studies have not explored how charitable organizations with a crisis history choose crisis response strategies in accidental crises. Moreover, charities often lack the accountability structures and mechanisms that are usually in place in other enterprises; thus, when an issue emerges, public trust is even more negatively impacted.5 Given the findings of previous studies, the present study sought to determine what the most appropriate crisis response strategy is for a charity with a crisis history in the midst of an accidental crisis. We thus hypothesized the following.

H2: If a charity has a crisis history, the most appropriate crisis response strategy in an accidental crisis will be the rebuild strategy.

Another related area of research concerns whether charities with different types of crisis history need to use rebuild strategies when accidental crises occur. Using the types of crisis events, crisis history can be divided into three categories: victim crisis history, accidental crisis history, and preventable crisis history. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, since a crisis history will increase the attribution of responsibility and trust threat of the current crisis, the diminish strategy cannot effectively repair trust, so the rebuild strategy should be adopted. However, previous research has shown that different types of crisis history have different effects on trust repair in a current crisis. Wei16 found that the public’s knowledge of a victim crisis history, which was caused by external factors, did not affect their willingness to forgive or the reparation of trust in a current crisis; however, an accidental or preventable crisis history, which are caused by internal factors, had a negative influence on public forgiveness. This shows that rebuild is not necessarily the most appropriate crisis response strategy for charities with different types of crisis history. Based on the above evidence, we concluded that a victim crisis history as an external-cause crisis history has no impact on a current accidental crisis; therefore, charitable organizations with a victim crisis history can adopt the same diminish strategy as in the first crisis. A history of preventable and accidental crises as internal-causes crisis history will increase the attribution of responsibility and trust threat in a current accidental crisis. Therefore, charities with a history of preventable and accidental crises should adopt rebuild strategies in accidental crises. According to all of the above, we proposed the following hypotheses.

H3: If a charity has a victim crisis history, the most appropriate crisis response strategy in the face of an accidental crisis is diminish. H4: If a charity has an accidental crisis history, the most appropriate crisis response strategy in the face of an accidental crisis is rebuild. H5: If a charity has a preventable crisis history, the most appropriate crisis response strategy in the face of an accidental crisis is rebuild.

In the present research, we conducted two studies to investigate how to best repair the public’s trust in a charity during an accidental crisis. In Study 1, we adopted a 2×2 between-subjects design to confirm the most appropriate crisis response strategy for a charity (no crisis history vs. crisis history) in an accidental crisis. In Study 2, we adopted a 3×2 between-subjects design to investigate the most appropriate crisis response strategy for a charity (victim crisis history vs. accidental crisis history vs. preventable crisis history) in an accidental crisis. Both studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Human Experiment Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Normal University. All participants provided written informed consent. The participants were informed about the study purpose and were informed that they could withdraw their participation in the research at any time and without any consequences.

Participants and Methods

Study 1

Study 1 explored the crisis response strategies that charities with and without a crisis history could adopt in a current accidental crisis. It was hypothesized that in an accidental crisis, the most appropriate crisis response strategy for a charity without a crisis history is a diminish strategy, and the most appropriate crisis response strategy for a charity with a crisis history is a rebuild strategy.

Participants and Design

After advertising the study, 177 university students (89 women, M = 20.82 years, SD = 2.82) were recruited from a university in Zhejiang. Study 1 used a 2 (crisis history: no crisis history vs. crisis history) × 2 (crisis response: diminish vs rebuild) between-subjects factorial experimental design. The dependent variable was the public trust level in charity A.

Procedure and Stimuli

A six-step procedure was employed for Study 1. First, the participants were asked to fill in the scales measuring the control variables. They then read brief background information on charity A (see Supplementary Material 1), and the participants in the crisis history condition were asked to read a crisis history material (see Supplementary Material 2). The participants then read a scenario describing the accidental crisis faced by charity A (see Supplementary Material 3) and reported their trust levels (T1). Thereafter, a scenario description of the diminish and rebuild strategies (see Supplementary Material 4) was given to the participants, and they were asked to report their trust levels again (T2). The procedure for Study 1 is shown schematically in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 Study 1 experimental procedure. Abbreviations: TFS, Trait Forgiveness Scale; ITS, Interpersonal Trust Scale. |

The background information on charity A was adapted from the charitable organization materials of Hou12 (see Supplementary Material 1). To avoid the influence of previous reputation and type of charity, we adopted a virtual charity A for our study and delete the description of the type of charity. The crisis history material described a large catering invoice from charity A that once circulated on the Internet (see Supplementary Material 2). Two strategies were selected from each cluster to manipulate the crisis response strategy. From the diminish cluster, we combined the “excuse” and “justification” strategies into one.7 From the rebuild cluster, we chose the “apology” strategy. The descriptions for crisis response strategy are shown in Supplementary Material 4.

Measures

Interpersonal Trust

Based on the work of Ding,17 we measured interpersonal trust using a 10-item questionnaire, which is a Chinese version of Rotter’s18 Interpersonal Trust Scale (ITS). Answers were scored on a 5-point Likert scale (ɑ = 0.69), with scores ranging from 0 (very inconsistent) to 5 (very consistent). A sample question is “There is more and more hypocrisy in our society.”

Trait Forgiveness

Based on the work of Zhang,19 we measured trait forgiveness using a 10-item questionnaire, which is the Chinese version of Berry’s20 Trait Forgiveness Scale (TFS). Answers were scored on a 5-point Likert scale (ɑ = 0.83), with scores ranging from 0 (very inconsistent) to 5 (very consistent). A sample question is “I always forgive those who have hurt me.”

Charity Trust

A 4-item trust scale by Hou12 was used to assess charity trust in the different stages of the study. Answers were scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale, with scores ranging from 0 (very inconsistent) to 7 (very consistent). Sample questions include “Charity A always acts in the best interest of their cause,” “Charity A conducts its operations ethically,” “Charity A keeps its promises,” and “Overall, I trust charity A.” In the present study, the internal consistency at T1 was ɑ = 0.877, and the internal consistency at T2 was ɑ = 0.861.

Pre-Tests

Pre-Test 1

For the main study, 30 respondents participated in a task to check the validity of an accidental crisis scenario. We used a within-subjects design, and all respondents read pre-written material for the three types of crises (victim, accidental, and preventable), which are shown in Supplementary Material 3. To remove order effects, the order of the crisis materials was randomly assigned. According to the SCCT,7,8 crisis types can be manipulated through the assessment of locus of causality and controllability. Moreover, familiarity may influence the respondents’ judgments. Therefore, in Pre-test 1, the dependent variables were familiarity, locus of causality, and controllability.

Familiarity with the crisis was measured by a single item: “How familiar are you with crisis events?” This item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with answers ranging from 1 (not at all familiar) to 5 (very familiar). One-factor repeated-measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) showed no significant difference in the familiarity scores between the three types of crises, F(1, 29)=0.563, p> 0.05, ηp2=0.019.

We measured the locus of causality for a crisis using a 2-item questionnaire from the work of Hou.12 The questions were “The cause of this transgression is external to charity A” and “The cause of this transgression reflects an aspect of charity A”. Answers were scored on a 7-point Likert scale. The results showed that in the victim crisis condition (M = 5.03, SD = 1.52), respondents perceived charity A as significantly less responsible than in the accidental crisis (M = 10.57, SD = 2.62, p < 0.001) and preventable crisis conditions (M = 11.667, SD = 2.56, p < 0.001). There were no significant differences between the accidental crisis (M = 10.57, SD = 2.62) and preventable crisis conditions (M = 11.67, SD = 2.56, p > 0.05).

We measured controllability for a crisis using a 2-item questionnaire by Hou.12 The questions were “The transgression of charity A is manageable” and “The transgression of charity A is something over which it has power”. Answers were scored on a 7-point Likert scale. The results showed that in the victim crisis condition (M = 6.3, SD = 1.84), respondents perceived charity A to be significantly less responsible than in the accidental crisis (M = 9.6, SD = 0.81, p < 0.001) and preventable crisis conditions (M = 12.23, SD = 1.73, p < 0.001). Moreover, there were significant differences between the accidental crisis (M = 9.6, SD = 0.81) and preventable crisis conditions (M = 12.23, SD = 1.73, p < 0.001). The controllability of the accidental crisis (M=9.6, SD=0.81) was significantly lower than that of the preventable crisis (M = 12.23, SD = 1.73, p < 0.001).

Therefore, we adopted the accidental crisis material for the main study based on these results.

Pre-Test 2

Forty respondents participated in an order task to check for the manipulation of crisis response strategy. We used a within-subjects design, and the respondents were instructed to read two crisis response scenarios and then order them to answer two single items after reading each scenario: “Charity offers an excuse or a rationalization explanation for the incident” and “Charity apologized for the incident”.” Answers were scored on a 7-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 1 (do not at all agree) to 7 (very much agree). When using the score of “Charity offers an excuse or a rationalization explanation for the incident” as the dependent variable, the results showed that the diminish strategy score (M = 5.65, SD = 1.001) was significantly higher than the rebuild strategy score (M = 4.73, SD = 1.58, t(39)=3.32, p < 0.05). When using the score of “Charity apologized for the incident” as the dependent variable, the results showed that the diminish strategy score (M = 4.15, SD = 1.85) was significantly lower than the rebuild strategy score (M = 6.18, SD = 1.03, t(39)=−5.84, p < 0.001). Based on these results, we adopted the two crisis response strategies for the main study.

Results

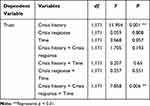

A 2 (crisis history) × 2 (crisis response) × 2 (time) three-factor repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to examine the effects on charity trust. We accounted for interpersonal trust, trait forgiveness, and gender as additional variables that may influence the experimental results and were thus considered as covariates. The ANOVA results showed that the main effect of crisis history on charity trust was significant F(1,171)=11.954, p=0.001, ηp2= 0.065 (see Table 1). The least significant difference (LSD) procedure revealed that the trust of the participants in the crisis history condition (M =16.3, SD = 4.38) was significantly lower than that in the no crisis history condition (M = 18.646, SD = 4.23).The ANOVA results also showed a significant triple interaction, ie, crisis history × crisis response × time (F(1, 171) = 7.858, p < 0.05, ηp2= 0.044; see Table 1). The post hoc tests indicated that in the no crisis history condition after participants read the diminish strategy, T2 (M=20.044, SD =3.51) was significantly higher than T1 (M=18.556, SD =5.922), p < 0.05. After participants read the rebuild strategy, there were no significant differences between T2 (M=17.636, SD =4.254) and T1 (M=18.318, SD =4.954), p > 0.05. In the crisis history condition, after participants read the diminish strategy, there were no significant differences between T2 (M=15.818, SD =4.364) and T1 (M=15.796, SD =4.365), p > 0.05. After participants read the rebuild strategy, T2 (M=17.523, SD =5.227) was significantly higher than T1 (M=16.068, SD =5.3), p < 0.05 (see Figure 2).

|

Table 1 Results of the 3-Factorial Repeated-Measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) in Study 1 |

|

Figure 2 Trust level under different crisis history context in Study 1. |

Discussion

The results of Study 1 showed that the most appropriate crisis response strategy for a charity in an accidental crisis is to utilize a diminish strategy. These results support H1 and are consistent with the SCCT Crisis Response Strategy Guidelines. However, if a charity has a crisis history, the most appropriate crisis response strategy in an accidental crisis would be to utilize a rebuild strategy. These results support H2 and the theoretical hypothesis of Coombs11 that given the background of a crisis history, rebuild strategies should be adopted in accidental crises to repair trust. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that different types of crisis histories have different effects on trust repair in current crisis events.16 The crisis history materials in Study 1 did not specify the type of crisis history. Therefore, we designed Study 2 to explore the most appropriate crisis response strategies for charities with crises histories of different types in the face of an accidental crisis.

Study 2

In Study 2, we explored the strategies that charities with three different crisis histories should adopt in times of accidental crisis. We hypothesized that in an accidental crisis, charities with a victim crisis history should adopt a diminish strategy, while charities with an accidental or preventable crisis history should adopt a rebuild strategy.

Participants and Design

After advertising the study, 236 university students (117 women, M = 21.08 years, SD = 3.26) were recruited from a university in Zhejiang. Study 2 used a 3 (crisis history: victim vs. accidental vs. preventable) × 2 (crisis response: diminish vs. rebuild) between-subjects design. The dependent variable was the public’s trust level in charity A. To manipulate the crisis history, we compiled three crisis history scenarios based on the SCCT and performed the same manipulation check as in Study 1. The accidental crisis scenario and the two crisis response strategies were the same as in Study 1.

Procedure and Stimuli

The procedure for Study 2, which was the same as that of Study 1, consisted of six steps. The only change was that participants were asked to read different types of crisis histories when reading brief background information on charity A. The procedure for Study 2 is shown schematically in Figure 3.

|

Figure 3 Study 2 experimental procedure. Abbreviations: TFS, Trait Forgiveness Scale; ITS, Interpersonal Trust Scale. |

The victim crisis history material described a rumor regarding charity A; the accidental crisis history material described an uncontrollable work error within charity A; and the preventive crisis history material described the illegal behavior of charity A. The crisis response strategy materials were the same as in Study 1. The three crisis history scenarios are shown in Supplementary Material 5.

Measures

The measures of charity trust and control variables were the same as those in Study 1.

Pre-Tests

For the main study, 30 respondents participated in a task to check the validity of the crisis history. We used a within-subjects design, and all respondents read the three crisis histories (victim, accident, and preventable). To remove order effects, the order of the crisis history materials was randomly assigned. Similar to Pre-test 1 in Study 1, the dependent variables were familiarity, locus of causality, and controllability.

The one-factor repeated-measures ANOVA results showed no significant difference in the familiarity scores between the three types of crises, F(1, 29) = 0.858, p > 0.05, ηp2 = 0.029.

When the locus of causality was the dependent variable, the results showed that in the victim crisis history condition (M = 3.53, SD = 2.09), respondents perceived charity A to be less responsible than in the accidental crisis (M = 12.26, SD = 2.03, p < 0.001) and preventable crisis history conditions (M = 13.27, SD = 1.17, p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between the accidental crisis (M = 12.26, SD = 2.03) and preventable crisis history conditions (M = 13.27, SD = 1.17, p > 0.05).

When controllability was the dependent variable, the results showed that in the victim crisis history condition (M = 5.17, SD = 2.73), respondents perceived charity A to be less responsible than in the accidental crisis (M = 11.5, SD = 2.36, p < 0.001) and preventable crisis history conditions (M = 13.3, SD = 1.02, p < 0.001). Moreover, the controllability score in the accidental crisis history condition (M = 11.5, SD = 2.36) was significantly lower than in the preventable crisis history condition (M = 13.3, SD = 1.02, p < 0.001). Based on these results, we adopted the three crisis scenarios for the main study.

Results

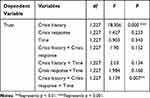

A three-factor repeated-measures ANOVA 3 (crisis history) × 2 (crisis response) × 2 (time) was conducted to examine the effects on charity trust. Interpersonal trust traits, forgiveness, and gender were used as covariates. The ANOVA results showed the main effect of crisis history on trust was significant: F(1, 227) = 18.306, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.139 (Table 2). The LSD procedure revealed that participants perceived lower trust in the preventable crisis history condition (M = 14.9, SD = 4.97) than in the victim (M = 19.15, SD = 4.31, p < 0.001) and accidental crisis history conditions (M = 17.24, SD = 4.29, p < 0.05). The findings also confirmed a significant triple interaction, ie, crisis history × crisis response × time (F(1, 227) = 5.139, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.043; see Table 2). Post hoc tests indicated that in the victim crisis history condition, after participants read the diminish strategy, T2 (M = 20.53, SD = 3.6) was borderline significantly higher than T1 (M = 19.7, SD = 3.45), p = 0.075. After participants read the rebuild strategy, no significant differences were found between T2 (M = 17.97, SD = 5.44) and T1 (M = 18.36, SD = 4.76), p = 0.378. In the accidental crisis history condition, after participants read the diminish strategy, T2 (M = 18.43, SD = 4.63) was significantly higher than T1 (M = 16.88, SD = 4.43), p < 0.001; after participants read the rebuild strategy, no significant differences were found between T2 (M = 16.85, SD = 4.61) and T1 (M = 16.79, SD = 4.47), p > 0.05. In the preventable crisis history condition, after participants read the diminish strategy, no significant differences were found between T2 (M = 14.79, SD = 5.76) and T1 (M = 14.28, SD = 4.899), p > 0.05; after participants read the rebuild strategy, T2 (M = 16.08, SD = 4.959) was significantly higher than T1 (M = 14.46, SD = 5.23), p < 0.001 (see Figure 4).

|

Table 2 Results of the 3-Factorial Repeated-Measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) in Study 2 |

|

Figure 4 Trust repair level under different crisis history context in Study 2. |

Discussion

The results of Study 2 showed that under the victim crisis history condition, the difference between T2 and T1 when using the diminish strategy was only marginally significant. However, there was no significant difference between T2 and T1 when using the rebuild strategy. Therefore, H3 was partially supported. If a charity has a victim crisis history, the most appropriate crisis response strategy in an accidental crisis would be diminish. Under the accidental crisis history condition, diminish strategies improved trust after an accidental crisis, but rebuild strategies did not. These results did not support H4. If a charity has an accidental crisis history, the most appropriate crisis response strategy in an accidental crisis would be diminish. Finally, under the preventable crisis history condition, diminish strategies did not improve trust after an accidental crisis, but rebuild strategies did. These results support H5. If a charity has a preventable crisis history, the most appropriate crisis response strategy in an accidental crisis would be rebuild.

General Discussion

The results of the present research showed that individuals were more likely to trust charities during an accidental crisis when the charity responded by using a diminish strategy. These results support H1, which is consistent with Coombs’ theoretical hypothesis and many research results. A diminish strategy matched with an accidental crisis of medium responsibility can effectively repair trust,13 the public’s trust in the organization decreases when they see that the organization actively adopts rebuild strategy.14 However, the aforementioned results are inconsistent with the findings of Sisco’s study,10 which showed no differences between the diminish strategy and the more active rebuild strategy in such times of crisis.10 However, the accident scenario used in Sisco’s study was an uncontrollable food recall that greatly involved another organization. Therefore, the participants may not have attributed even a moderate level of responsibility to the nonprofit food bank, and instead placed all blame on the external organization that caused the problem. In contrast, the accident scenario used in our study was an unintentional mistake. Thus, the participants attributed a moderate level of responsibility to charity A. This may be a reason for the discrepancy between our findings and those of Sisco. Another reason for the inconsistent results of may be related to inconsistent statistical methods. To avoid the influence of inter-group differences, repeated-measures ANOVA was used to compare the level of trust before and after the crisis response. In Sisco’s study, ANOVA was used to compare the organizational image of participants after they read about the crisis response. These reasons may lead to our findings being different from those of Sisco’s study.

The results of Study 1 also indicate that individuals are more likely to trust charitable organizations in an accidental crisis when organizations with a crisis history use rebuild strategies. The results also support H2, which is consistent with Coombs’ theoretical hypothesis, namely that charities with a crisis history should adopt a rebuild strategy during an accidental crisis.11 Previous research has also shown that when an organization has a crisis history, accident crises that were originally thought to pose a moderate reputational threat can pose a serious threat.11 This is because the charity has a crisis history. The public, generally thinking that accident crises are stable, makes a higher attribution of crisis responsibility to the charity and thinks that its persistent internal problems are the reason for the crisis happening again. Therefore, if the charity continues to adopt a diminish strategy, it will cause greater public doubt and dissatisfaction and further damage to the public’s trust. Hence, organizations with a crisis history need to treat accidental crises as preventable crises, ie, they should adopt rebuild strategies.11 The sense of responsibility and repentance of a charity—as reflected in its rebuild strategy—will lessen public dissatisfaction, dilute the negative impression of the organization, and repair public trust.

As shown by Study 2, a charity with a crisis history does not necessarily need to adopt rebuild strategies in times of accident crisis. The results of Study 2 indicated that under the victim crisis history condition, a charity can adopt a diminish strategy when faced with an accidental crisis. This result is consistent with the study by Wei,16 which found that a victim crisis history, as an externally caused crisis history, will not increase the attribution of responsibility and trust threat in a current crisis.

The results of Study 2 also showed that under the accidental crisis history condition, the diminish strategy of a charity facing an accidental crisis can effectively repair trust. This result suggests that an accidental crisis history may not influence the attribution of responsibility and reputation threat in a current accident crisis. This is not consistent with H4 or Wei’s results.16 Previous studies16 have suggested that an accidental crisis history may lead to a higher attribution of responsibility and lower trust evaluation by the public in a current crisis, and that diminish strategies cannot effectively repair the damaged organizational trust. The likely reason is that there is a bigger difference between our accidental crisis history material and the accidental crisis material, so the public may think that the causes of the current accidental crisis are not long-term. The public believes that the current accidental crisis is simply an uncontrollable accident, and a diminish strategy can effectively repair trust.

Moreover, the results of Study 2 showed that under the preventable crisis history condition, charities need to adopt rebuild strategies to repair trust when faced with an accidental crisis. This result is consistent with that of Wei’s study16 as well as H5. As the most serious, an internally caused crisis, a preventable crisis history will significantly increase the attribution of responsibility and reputation threat in a current accidental crisis, and the public may think that the current accidental crisis was deliberately caused by the charitable organization. Therefore, a rebuild strategy must be adopted to gain public forgiveness and repair damaged trust.

Limitations and Future Research

This research had several limitations. First, even though an experimental situation is more rigorous, the perception formed by reading written materials remains different from a real-life situation in reality in terms of authenticity and experience.21 Therefore, in future research, real materials and qualitative interviews could be used to study crisis events faced by real charitable organizations. Second, in the present experiment, the time interval between providing charity crisis materials and charity crisis response strategy materials to the participants was almost negligible, which could be regarded as simultaneous provision. In reality, however, the emergence of crises and the response of charitable organizations often do not coincide. Future studies could use longitudinal data collection to examine the impact of different types of crises on the extent of trust damage and repair, as time plays an important role in the process of trust violation and repair. Third, although the college student population is one of the most active participant groups in the charitable sector12 and constituted a salient population in this study, this work should be replicated with groups with different demographics and cultures. Fourth, the charitable organization in our study was generic, but many factors involved in the trust of charitable organizations will vary somewhat across charity types.22 Thus, these results can be verified using different types of charities. Finally, we must acknowledge that while there were statistically significant findings in the study, the effect sizes were small. Nonetheless, it should be noted that effect sizes in social science research are typically small.23 Regardless, this speaks to the need to conduct replication studies examining this phenomenon further.

Conclusion

Charities should adopt a diminish strategy after experiencing a first accidental crisis. Charities with a victim or accidental crisis history should adopt a diminish strategy when faced with a current accidental crisis. However, if the charity has a preventable crisis history, the rebuild strategy is the most appropriate response to a current accidental crisis. These results suggest that charities should first consider whether there is a crisis history and its type, and then adopt an appropriate crisis response strategy to restore trust.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Major Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China (Award no. 18ZDA165) and the Open research Fund of Zhejiang Key Laboratory of Intelligent Education Technology and Application (Award no. jykf21022).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Moorman C, Zaltman G, Deshpande R. Relationships between providers and users of market research: the dynamics of trust within and between organizations. J Mark Res. 1992;29(3):314–328. doi:10.1177/002224379202900303

2. Hou J, Zhang C, King R. Understanding the dynamics of the individual donor’s trust damage in the philanthropic sector. Voluntas. 2017;28(2):1–24. doi:10.1007/s11266-016-9681-8

3. Wymer W, Becker A, Boenigk S. The antecedents of charity trust and its influence on charity supportive behavior. J Philanthr Mark. 2021;26(2):e1690.

4. Hou J, Xiao R, Huang Z, et al. A social computing approach to the cause diffusion for individual donor’s trust damage. Inter J Comput Sci Math. 2015;6(2):152–165. doi:10.1504/IJCSM.2015.069462

5. Haupt B, Azevedo L. Crisis communication planning and nonprofit organizations. Disaster Prev Manage Inter J. 2021;30(2):163–178. doi:10.1108/DPM-06-2020-0197

6. Meng W, Youxin W. Trust crisis and charity donation: an empirical study based on the provincial data in 2002—2016. Manage Rev. 2020;32(8):244.

7. Coombs WT. Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: the development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corp Repu Rev. 2007;10(3):163–176. doi:10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550049

8. Coombs WT, Holladay SJ. Helping crisis managers protect reputational assets: initial tests of the situational crisis communication theory. Manag Commun Q. 2002;16(2):165–186. doi:10.1177/089331802237233

9. Roberts C . An experimental investigation into the impact of crisis response strategies and relationship history on relationship quality and corporatecredibility [dissertation]. Tampa: University of South Florida; 2009.

10. Sisco HF. Nonprofit in crisis: an examination of the applicability of situational crisis communication theory. J Public Relat Res. 2012;24(1):1–17. doi:10.1080/1062726X.2011.582207

11. Coombs WT. Impact of past crises on current crisis communication: insights from situational crisis communication theory. J Bus Commun. 2004;41(3):265–289. doi:10.1177/0021943604265607

12. Hou J, Zhang C, Guo H. How nonprofits can recover from crisis events? The trust recovery from the perspective of causal attributions. Voluntas. 2020;31(1):71–93. doi:10.1007/s11266-019-00176-7

13. Bundy J, Pfarrer MD. A burden of responsibility: the role of social approval at the onset of a crisis. Acad Manage Rev. 2015;40(3):345–369. doi:10.5465/amr.2013.0027

14. Siomkos GJ, Kurzbard G. The hidden crisis in product-harm crisis management. Eur J Mark. 1994;28(2):30–41. doi:10.1108/03090569410055265

15. Eaddy L, Yan J. Crisis history tellers matter: the effects of crisis history and crisis information source on publics’ cognitive and affective responses to organizational crisis. Corp Commun Inter J. 2018;23(2):226–241. doi:10.1108/CCIJ-04-2017-0039

16. Wei HY, Wei W. The effects of past crises on consumer forgiveness of current product-harm crisis. Econ Manage J. 2011;33(08):101–108.

17. Ding WY, Peng KP. Correction and revision of Chinese-translated interpersonal trust scale. Mon J Psychol. 2020;15(06):4–7.

18. Rotter JB. A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust. J Personal. 2010;35(4):651–665. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1967.tb01454.x

19. Zhang DH, Luo Q. Relationship between personality traits and forgiveness. Chin J Nutr Psychol. 2011;19(1):100–102.

20. Berry JW, Worthington JEL. Forgivingness, relationship quality, stress while imagining relationship events, and physical and mental health. J Couns Psychol. 2001;48(4):447. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.48.4.447

21. Coombs WT, Tachkova ER. Scansis as a unique crisis type: theoretical and practical implications. J Commun Manage. 2019;23(1):72–88. doi:10.1108/JCOM-08-2018-0078

22. Keating VC, Thrandardottir E. NGOs, trust, and the accountability agenda. Brit J Polit Inter Relat. 2017;19(1):134–151. doi:10.1177/1369148116682655

23. Holland D, Seltzer T, Kochigina A. Practicing transparency in a crisis: examining the combined effects of crisis type, response, and message transparency on organizational perceptions. Public Relat Rev. 2021;47(2):102–117. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2021.102017

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.