Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 13

Reliability and validity of the Maltese version of the Perception of Anticoagulant Treatment Questionnaire (PACT-Q)

Authors Riva N , Borg Xuereb C, Makris M , Ageno W, Gatt A

Received 4 March 2019

Accepted for publication 12 April 2019

Published 19 June 2019 Volume 2019:13 Pages 969—979

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S207498

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Video abstract presented by Christian Borg Xuereb, Nicoletta Riva and Alex Gatt.

Views: 238

Nicoletta Riva,1 Christian Borg Xuereb,2 Michael Makris,3 Walter Ageno,4 Alex Gatt1

1Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, University of Malta, Msida, Malta; 2Department of Gerontology and Dementia Studies, Faculty for Social Wellbeing, University of Malta, Msida, Malta; 3Sheffield Haemophilia and Thrombosis Centre, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK; 4Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Insubria, Varese, Italy

Purpose: Anticoagulant therapy has an impact on the health-related quality of life, as it is a chronic treatment for most clinical indications and also requires some lifestyle changes. Since there was no validated questionnaire available in the Maltese language, the aim of our study was to translate and validate the Perception of Anticoagulant Treatment Questionnaire (PACT-Q2).

Patients and methods: The PACT-Q2 explores two dimensions (convenience and anticoagulant treatment satisfaction). Forward and backward translations were performed. The Maltese version of the PACT-Q2 was administered to 174 patients on warfarin treatment enrolled from different anticoagulation clinics in Malta. Reliability was assessed through internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) and test-retest (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC]). Validity was assessed through floor/ceiling effect, factor analysis (root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA], standardized root mean squared residual [SRMR], goodness-of-fit index [GFI], adjusted goodness-of-fit index [AGFI], comparative fit index [CFI]), subscales correlation and known-group validity.

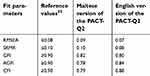

Results: Reliability was very good for the convenience subscale (Cronbach’s alpha 0.86, ICC 0.87), but less good for the satisfaction subscale (Cronbach’s alpha 0.62, ICC 0.40). Floor effect was 0%; ceiling effect was low (6.3% convenience, 1.2% satisfaction). Fit parameters were close to acceptable cut-offs (RMSEA =0.09, SRMR =0.10, GFI =0.82, AGFI =0.78, CFI =0.79). There was no correlation between the two subscales (r=0.01, p=0.83). Patients with history of bleeding showed lower convenience (r=−0.16, p=0.08) and lower satisfaction (r=−0.21, p=0.01).

Conclusions: Our results support the finding that the Maltese translation of the PACT-Q2 is a valid and reliable instrument.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, psychometrics, quality of life, surveys and questionnaires, venous thromboembolism, warfarin

Introduction

Anticoagulant therapy is the mainstay treatment for the primary and secondary prevention of thromboembolic complications in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), venous thromboembolism (VTE) and mechanical heart valve replacement.1 However, since it is a chronic treatment for most clinical indications, it can affect the health-related quality of life.2,3 For instance, vitamin K antagonists (VKA), such as warfarin, have several food and drug interactions and require dose adjustment, therefore mandating periodic blood testing of the international normalized ratio (INR).1

Since patients’ negative beliefs related to medications can result in non-adherence to chronic treatment and therefore reduced effectiveness,4,5 specific questionnaires have been developed to assess the satisfaction associated with the anticoagulant treatment. These include the Perception of Anticoagulant Treatment Questionnaire (PACT-Q),6 the Duke Anticoagulation Satisfaction Scale (DASS),7 the Anti-Clot Treatment Scale (ACTS),8 the Deep Venous Thrombosis Quality of Life questionnaire (DVTQOL)9 and the Pulmonary Embolism Quality of Life Questionnaire (PEmb-QoL).10 However, there was no validated questionnaire available in the Maltese language.

We chose to translate the PACT-Q and the DASS because they have already been translated into several languages and applied to patients with a broad range of clinical indications to the anticoagulant treatment.7,11–15 The aim of this study was to assess the psychometric properties (reliability and validity) of the Maltese version of the PACT-Q. The psychometric properties of the Maltese version of the DASS have been reported in a separate paper.

Materials and methods

The perception of anticoagulant treatment questionnaire (PACT-Q)

The PACT-Q is divided into two parts: the PACT-Q1 measures the expectations associated with the anticoagulant treatment and is administered prior to treatment initiation, while the PACT-Q2 measures the convenience and the satisfaction and is administered during anticoagulant treatment.6,11 In the PACT-Q2, the “Convenience” dimension comprises 13 items (from the combination of the original sections B “Convenience” and C “Burden of Disease and Treatment”), while the “Anticoagulant Treatment Satisfaction” dimension comprises 7 items (section D).11 All items can be answered according to a 5-point Likert scale (not at all, a little, moderate, a lot, extremely). During the analysis, the items of “Convenience” are reversed, summed and rescaled on a 0–100 scale; the items of “Anticoagulant Treatment Satisfaction” are summed and rescaled on a 0–100 scale. Therefore, higher total scores correspond to higher convenience/satisfaction.11

Permission to translate and use the PACT-Q was obtained from Sanofi Aventis/Mapi Research Trust. The linguistic validation process followed published guidelines,16,17 with two forward translations from English to Maltese and a backward translation from Maltese to English, performed by different people (a professional translator, a health psychologist, and a speech and language pathologist), all bilingual in English and Maltese. A pilot testing was initially performed by completing and discussing the questionnaire with 5 patients on long-term oral anticoagulant treatment (not included in the analysis).

Study population

We administered the Maltese version of the PACT-Q2 to 174 patients receiving warfarin treatment. They were enrolled from the Anticoagulation Clinics at Mater Dei Hospital (Msida) and at 5 Health Centers (Cospicua, Floriana, Mosta, Qormi, Rabat) in Malta. Blood samples for INR testing at Mater Dei Hospital are collected using traditional venepuncture and INR is performed using laboratory coagulometers, whilst at the Health Centres INR is tested using point-of-care devices. Patients with cognitive impairment, dementia or major psychiatric disorders (such as schizophrenia) were excluded.

Two authors (NR, CBX) distributed the questionnaires between July 2017 and February 2018. Since we considered patients already receiving the anticoagulant treatment, only the PACT-Q2 was administered. Patients were also asked to complete a form on sociodemographic data. To ensure anonymity, questionnaires were identified using a code. In case of missing answers, the researchers associated the code with the provided demographic details and patients were contacted by phone.

During the same period, 157 patients on warfarin enrolled from the same Anticoagulation Clinics completed the original English version of the PACT-Q2.

A random sample of 40 patients underwent the following test-retest after 1–2 weeks (10 patients for each type): Maltese–Maltese; English–English; Maltese–English; English–Maltese.

This study was approved by the University of Malta Research and Ethics Committee (Ref No 07/2016) and all patients signed a written informed consent form before inclusion.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean±standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were reported as counts and percentages. Continuous variables were compared using the Student’s independent samples t-test, while categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square or the Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate.

We evaluated the reliability of the Maltese version of the PACT-Q2 through internal consistency and test–retest.18 The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to assess the internal consistency, with a value ≥0.70 indicating high internal consistency.19

A test–retest was performed to assess reproducibility, and we calculated the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for the intra-language correlation (Maltese-Maltese and English–English test–retest). Values between 0.60 and 0.74 are considered acceptable.20 For the cross-language correlation (Maltese–English and English–Maltese test-retest pooled together), we calculated the raw and the adjusted cross-language correlation (dividing the raw cross-language correlation by the square-root of the product of the intra-language correlations, to adjust for score unreliability).21,22

We evaluated the validity of the Maltese translation of the PACT-Q2 through floor and ceiling effect, factor analysis, construct validity and known-group validity. Floor and ceiling effect occur when more than 15% of the respondents achieve the lowest or the highest possible score, respectively.23

In the factor analysis, convergent and discriminant validity were evaluated. The convergent validity criterion was considered met when the correlation between each item and its dimension was ≥0.40, while the discriminant validity criterion was considered met when each item showed higher correlation with its dimension than the other.24 We conducted an exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation to examine the structure of the PACT-Q2. A subsequent confirmatory factor analysis provided the following fit parameters: root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA ≤0.05 good fit, ≤0.08 acceptable fit); standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR ≤0.05 good fit, ≤0.10 acceptable fit); goodness-of-fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) and comparative fit index (CFI), with values ≥0.90 considered acceptable.25

To examine construct validity, the Pearson’s correlation between different subscales was assessed.26 Known-group validity was assessed through Pearson’s correlation between the score of each PACT-Q2 subscale and the following variables: increasing age; male sex; living alone; primary school education only; paid employment; atrial fibrillation; anticoagulant treatment duration (>5 years); INR in the therapeutic range at enrolment; time-within-therapeutic-range (TTR, calculated according to the Rosendaal method)27 ≥70% in the previous year; hospitalization in the previous year; history of any bleeding during anticoagulant treatment (self-reported).

A sample size of at least 150 patients was planned, since recommendations suggest at least 50 patients23 and previous validation studies enrolled around 100 patients.28,29

The statistical software STATA SE v.12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and SAS v. 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA) were used for statistical analysis, with two-tailed p-values<0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

Baseline characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. The comparison between patients who completed the Maltese and the English version of the questionnaires has been already reported.

| Table 1 Characteristics of patients who completed the Maltese version of the PACT-Q2 |

There was no difference in the mean convenience score between the two cohorts (mean±SD 82.2±16.1 for the Maltese version vs 84.0±13.7 for the English version, p=0.28), while patients who completed the Maltese version showed a trend toward lower satisfaction score (65.2±11.5 vs 67.6±14.6, respectively, p=0.09), corresponding to lower anticoagulant treatment satisfaction.

Internal consistency

The internal consistency of the Maltese translation of the PACT-Q2 was good for the convenience subscale with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.86. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.62 for the satisfaction subscale, which is slightly below the standard acceptable cut-off of 0.70. However, the satisfaction subscale has only 7 items and one item (D2) showed poor correlation with the overall satisfaction subscale, showing both a low item-total correlation of ~0.3 and an increase of Cronbach’s alpha when deleted. However, D2 corresponds to the question “Do you feel that your anticoagulant treatment has decreased your symptoms?”, which might have a negative answer also in satisfied patients, if anticoagulation is used for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation or mechanical heart valves, and therefore does not have any impact on patients’ symptoms.

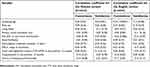

The English version of the PACT-Q2 also showed good internal consistency in our cohort with the following Cronbach’s alpha coefficients: 0.86 for the convenience subscale and 0.75 for the satisfaction subscale (Table 2).

| Table 2 Internal consistency of the Maltese and English versions of the PACT-Q2 |

Reproducibility

In the Maltese–Maltese test–retest, the ICC for the intra-language correlation was very good for the convenience subscale (0.87), but low (0.40) for the satisfaction subscale. In the English–English test–retest, ICC was 0.87 for the convenience subscale and 0.60 for the satisfaction subscale (Table S1).

For the cross-language correlation, the corresponding ICC was 0.51 and 0.52 and the adjusted ICC was 0.59 and 1.06 for the convenience and satisfaction subscales, respectively. When analyzed separately, ICC for the English–Maltese test–retest was 0.76 and 0.68 for the convenience and satisfaction subscales, while ICC for the Maltese–English test–retest was 0.43 and 0.41, respectively.

Floor and ceiling effect

When we analyzed the response distribution for each item of the PACT-Q2, reversing the items of the convenience subscale, a significant ceiling effect was observed for most of the questions. A significant floor effect was found only for question D2. The Maltese and the English version of the PACT-Q2 showed similar results in our study (Table S2).

We subsequently analyzed the results of each PACT-Q2 subscale: for the Maltese version, ceiling effect was 6.3% for convenience and 1.2% for satisfaction; for the English version, ceiling effect was 9.6% for convenience and 1.3% for satisfaction. Floor effect was 0% for all subscales in both languages.

Factor analysis

Results of the confirmatory factor analysis were acceptable. For the Maltese version of the PACT-Q2, SRMR=0.10 was within the acceptable limits; RMSEA=0.09 was slightly above the reference, while GFI=0.82, AGFI=0.78 and CFI=0.79 were slightly below the reference values (Table 3).

| Table 3 Results of the confirmatory factor analysis |

The rotated factor pattern is reported in Table S3. The convergent validity criterion was met by all items of the Maltese PACT-Q2, except B10, B11, C2 (for the convenience subscale) and D2, D3 (for the satisfaction subscale). All items met the discriminant validity criterion.

Correlation scale-subscales

There was no correlation between the convenience and the satisfaction subscales in the Maltese version of the PACT-Q2 (r=0.01, p=0.83), while a weak positive correlation was found in the English version (r=0.33, p<0.001).

Known-group validity

The Maltese version of the PACT-Q2 showed a negative correlation with previous bleeding. The correlation was statistically significant for the satisfaction subscale and borderline for the convenience subscale (Table 4).

| Table 4 Correlation between the PACT-Q2 and sociodemographic or clinical characteristics |

In the English version of the PACT-Q2, the convenience subscale showed a significant positive correlation with increasing age and male sex, and a significant negative correlation with full- or part-time paid employment, hospitalization and history of bleeding. The subscale satisfaction gave similar results, which were statistically significant only for male sex.

These findings suggest that advanced age and male sex are associated with greater satisfaction/convenience, while paid employment, hospitalization and previous bleeding are associated with lower satisfaction/convenience.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that the PACT-Q2 has been translated and validated in the Maltese language. The results of our study suggest that the Maltese version of the PACT-Q2 is a valid and reliable instrument. The psychometric properties were very good for the convenience subscale, whereas they were slightly lower for the satisfaction subscale.

The PACT-Q is a specific questionnaire that evaluates the quality of life of anticoagulated patients through simple questions. It was rigorously developed, translated in several languages and used in a number of studies enrolling patients with different clinical indications.14,30–32 While the PACT-Q1 assesses the expectations of the anticoagulant treatment, the PACT-Q2 evaluates the satisfaction and is used for patients already receiving the anticoagulant treatment. Patient-reported outcomes should always be considered, because of the relationship between low satisfaction, poor adherence and treatment failure.33–35 In our study, we translated the PACT-Q2 in Maltese and administered it to 174 patients on warfarin for different clinical indications, including atrial fibrillation, heart valve replacement and venous thromboembolism. A peculiarity of our study is the fact that during the same time-frame, the original English version of the PACT-Q2 was administered to 157 patients at the same centers, therefore allowing a comparison of the psychometric properties. This study design was possible because Malta is a bilingual country where both Maltese and English are official languages.36

We found that the reliability of the Maltese translation of the PACT-Q2 was very good for the convenience subscale (Cronbach’s alpha 0.86, ICC 0.87), while it was less so for the satisfaction subscale (Cronbach’s alpha 0.62, ICC 0.40). However, the satisfaction subscale showed lower reliability also in the English version of the PACT-Q2 (Cronbach’s alpha 0.75, ICC 0.60 in our study; Cronbach alpha 0.76 in the study by Prins et al).11 This finding can be partly explained by the lower number of items (13 questions in the convenience subscale vs 7 questions in the satisfaction subscale) and partly by a response bias. Response bias is common in patient-reported outcomes and occurs when participants’ responses are influenced by their belief of which answers are socially acceptable or which answers are expected by the researchers.37 The satisfaction subscale might have been particularly susceptible to response bias, due to the fact that several questions (D4-D7) ask directly the level of satisfaction with different aspects of the anticoagulant treatment (the level of independence, the appointments, the anticoagulant drug and the overall satisfaction). Participants might have felt more obliged to show that they were satisfied with the service, appointments, anticoagulant drug rather than risk reprisal on their treatment, even though the informed consent specified anonymity of data. Furthermore, although the retest was performed within two weeks, changes in the level of satisfaction might have occurred due to intercurrent clinical complications or differences of experience of service provision during following appointments for INR testing.

Validity of the Maltese translation of the PACT-Q2 was good. We observed a significant ceiling effect for most of the PACT-Q2 items when analyzed individually. However, when we considered the two subscales, floor effect was 0% and ceiling effect did not exceed 10% (being 6.3% for convenience and 1.2% for satisfaction). These results were even better than the original study of the PACT-Q2 which reported a ceiling effect of 22.1% for convenience and 3.3% for satisfaction.11 Results of the factor analysis were good, with fit parameters close to the acceptable cut-offs. Furthermore, all items met the discriminant validity criterion, while the convergent validity was met by all items except B10, B11, C2 (convenience subscale) and D2, D3 (anticoagulant treatment satisfaction subscale). Although previous studies did not report the fit parameters (RMSEA, SRMR, GFI, AGFI and CFI), items B10-B11 and D2-D3 did not meet the convergent validity criterion also in the original study by Prins et al.11 Correlation between the two PACT-Q2 subscales was weak, as previously reported,11 confirming that they cover different dimensions. The results of the known-group validity analysis showed that patients with history of bleeding had lower satisfaction. Although previous validation studies of the PACT-Q did not evaluate this group,11,12 lower scores on the convenience dimension of the PACT-Q2 were reported after bleeding events in a prospective study enrolling 807 atrial fibrillation patients on warfarin.31 Furthermore, lower satisfaction in anticoagulated patients with history of bleeding was already reported in validation studies of other specific questionnaires.7,38

Our study population shows some differences when compared to previous PACT-Q validation studies. Mean age was older (70 years), compared to 65 years in the study by Prins et al11 and 58 years in the study by Mohamed et al.12 We enrolled patients on oral anticoagulant treatment with VKA, while Prins et al11 considered also patients on treatment with idraparinux, which is a parenteral drug injected subcutaneously once weekly. Finally, we had a higher proportion of patients with primary school level of education (62%), compared to the study by Mohamed et al12 where only 28% had only primary school education or no education at all.

Our study has also some limitations which need to be acknowledged. First, we enrolled patients who were already on anticoagulant treatment; therefore, we could validate only the PACT-Q2. Second, although the PACT-Q has been developed for patients receiving different types of anticoagulants (oral or parenteral),6 we enrolled only patients on warfarin which was the main oral anticoagulant treatment in Malta at the time of patients enrolment. Nonetheless, the strengths of our study include the completeness of data, without any missing answers, and the rigorous process of translation and analysis.

Conclusion

Our results support the finding that the Maltese translation of the PACT-Q2 is a valid and reliable instrument, which can be used by health-care professionals when assessing Maltese-speaking anticoagulated patients.

Copyright

PACT-Q © 2007 Sanofi-Aventis, France. All rights reserved.

PACT-Q contact information and permission to use: Mapi Research Trust, Lyon, France. E-mail: [email protected] – Internet: www.proqolid.org

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the patients who completed the questionnaires and the staff of the Anticoagulation Clinics at Cospicua, Floriana, Mosta, Qormi, Rabat Health Centres and at Mater Dei Hospital for their help in patient recruitment. We would also like to thank Dr. Elayne Azzopardi (Speech and Language Pathologist, College of Medicine, Swansea University, Swansea, UK) and Dr. George Farrugia (Senior Lecturer, Department of Maltese, Faculty of Arts, University of Malta, Msida, Malta) for their contribution to the Maltese translation of the DASS, and Dr. Lorenza Bertù (Biostatistician, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Insubria, Varese, Italy) for her assistance in statistical analysis. This study was supported by a research grant from the University of Malta.

Disclosure

Nicoletta Riva reports grants from the University of Malta, during the conduct of the study. Walter Ageno reports grants and personal fees from Bayer, and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS Pfizer and Daiichi Sankyo, outside the submitted work. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Ageno W, Gallus AS, Wittkowsky A, et al. Oral anticoagulant therapy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2Suppl):e44S–88S. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2292

2. Borg Xuereb C, Shaw RL, Lane DA. Patients’ and physicians’ experiences of atrial fibrillation consultations and anticoagulation decision-making: A multi-perspective IPA design. Psychol Health. 2016;31(4):436–455. doi:10.1080/08870446.2015.1116534

3. Casais P, Meschengieser SS, Sanchez-Luceros A, Lazzari MA. Patients‘ perceptions regarding oral anticoagulation therapy and its effect on quality of life. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(7):1085–1090. doi:10.1185/030079905X50624

4. Phatak HM, Thomas J

5. Waterman AD, Milligan PE, Bayer L, Banet GA, Gatchel SK, Gage BF. Effect of warfarin nonadherence on control of the International normalized ratio. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(12):1258–1264. doi:10.1093/ajhp/61.12.1258

6. Prins MH, Marrel A, Carita P, et al. Multinational development of a questionnaire assessing patient satisfaction with anticoagulant treatment: the ‘Perception of anticoagulant treatment questionnaire‘ (PACT-Q). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:9. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-7-9

7. Samsa G, Matchar DB, Dolor RJ, et al. A new instrument for measuring anticoagulation-related quality of life: development and preliminary validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:22. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-2-22

8. Cano SJ, Lamping DL, Bamber L, Smith S. The anti-clot treatment scale (ACTS) in clinical trials: cross-cultural validation in venous thromboembolism patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:120. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-10-120

9. Hedner E, Carlsson J, Kulich KR, Stigendal L, Ingelgård A, Wiklund I. An instrument for measuring health-related quality of life in patients with deep venous thrombosis (DVT): development and validation of deep venous thrombosis quality of life (DVTQOL) questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:30. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-2-30

10. Cohn DM, Nelis EA, Busweiler LA, Kaptein AA, Middeldorp S. Quality of life after pulmonary embolism: the development of the PEmb-QoL questionnaire. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(6):1044–1046. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03341.x

11. Prins MH, Guillemin I, Gilet H, et al. Scoring and psychometric validation of the perception of anticoagulant treatment questionnaire (PACT-Q). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:30. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-7-30

12. Mohamed S, Razak TA, Hashim R. Translation, validation and psychometric properties of Bahasa Malaysia version of the perception of anticoagulant therapy questionnaire (PACTQ). Asian J Biomed Pharm Sci. 2015;5(48):18–22. doi:10.15272/ajbps.v5i48.730

13. Agnelli G, Gitt AK, Bauersachs R, et al. The management of acute venous thromboembolism in clinical practice - study rationale and protocol of the European PREFER in VTE registry. Thromb J. 2015;13:41. doi:10.1186/s12959-015-0071-z

14. De Caterina R, Brüggenjürgen B, Darius H, et al. Quality of life and patient satisfaction in patients with atrial fibrillation on stable vitamin K antagonist treatment or switched to a non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant during a 1-year follow-up: a PREFER in AF registry substudy. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2018;111(2):74–84. doi:10.1016/j.acvd.2017.04.007

15. Pelegrino FM, Dantas RA, Corbi IS, Da Silva Carvalho AR, Schmidt A, Pazin Filho A. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric properties of the Brazilian-Portuguese version of the Duke anticoagulation satisfaction scale. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(17–18):2509–2517. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03869.x

16. Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(2):268–274. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01434.x

17. Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186–3191.

18. Webb NM, Shavelson RJ, Haertel EH. Reliability coefficients and generalizability theory. In: Rao CR, Sinharay S, editors. Handbook of Statistics: Vol 26 Psychometrics. Holland: Elsevier; 2006:81–124.

19. Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;22(3):297–334. doi:10.1007/BF02310555

20. Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess. 1994;6(4):284–290. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284

21. Wood D, Qiu L, Lu J, Lin H, Tov W. Adjusting Bilingual ratings by retest reliability improves estimation of translation quality. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2018;49(9):1325–1339. doi:10.1177/0022022118789773

22. McCrae RR, Yik MS, Trapnell PD, Bond MH, Paulhus DL. Interpreting personality profiles across cultures: bilingual, acculturation, and peer rating studies of Chinese undergraduates. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(4):1041–1055.

23. Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):34–42. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012

24. Campbell DT, Fiske DW. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol Bull. 1959;56(2):81–105.

25. McDonald RP, Ho MH. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):64–82.

26. Streiner DL, Norman GR, Cairney J. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

27. Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJ, Briët E. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost. 1993;69:236–239.

28. Frey PM, Méan M, Limacher A, et al. Quality of life after pulmonary embolism: prospective validation of the German version of the PEmb-QoL questionnaire. Thromb Res. 2015;135(6):1087–1092. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2015.03.031

29. Rochat M, Méan M, Limacher A, et al. Quality of life after pulmonary embolism: validation of the French version of the PEmb-QoL questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:174. doi:10.1186/s12955-014-0174-4

30. Goette A, Kwong WJ, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Edoxaban therapy increases treatment satisfaction and reduces utilization of healthcare resources: an analysis from the EdoxabaN vs. warfarin in subjectS UndeRgoing cardiovErsion of atrial fibrillation (ENSURE-AF) study. EP Europace. 2018;20:1936–1943. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 29947751. doi:10.1093/europace/euy141

31. Kooistra HA, Piersma-Wichers M, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Veeger NJ, Meijer K. Impact of vitamin K antagonists on quality of life in a prospective cohort of 807 atrial fibrillation patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9(4):388–394. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002612

32. Obamiro KO, Chalmers L, Lee K, Bereznicki BJ, Bereznicki LRE. Anticoagulation knowledge in patients with atrial fibrillation: an Australian survey. Int J Clin Pract. 2018;72(3):e13072. doi:10.1111/ijcp.13072

33. Davis NJ, Billett HH, Cohen HW, Arnsten JH. Impact of adherence, knowledge, and quality of life on anticoagulation control. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(4):632–636. doi:10.1345/aph.1E464

34. Thomson Mangnall LJ, Sibbritt DW, Al-Sheyab N, Gallagher RD. Predictors of warfarin non-adherence in younger adults after valve replacement surgery in the South Pacific. Heart Asia. 2016;8(2):18–23. doi:10.1136/heartasia-2016-010751

35. Weernink MGM, Vaanholt MCW, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM, von Birgelen C, IJzerman MJ, van Til JA. Patients‘ priorities for oral anticoagulation therapy in non-valvular atrial fibrillation: a multi-criteria decision analysis. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2018;18(6):493–502. doi:10.1007/s40256-018-0293-0

36. Vella A. Languages and language varieties in Malta. Int J Biling Educ Biling. 2013;16(5):532–552. doi:10.1080/13670050.2012.716812

37. Mazor KM, Clauser BE, Field T, Yood RA, Gurwitz JH. A demonstration of the impact of response bias on the results of patient satisfaction surveys. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(5):1403–1417.

38. Radaideh KM, Matalqah LM. Health-related quality of life among atrial fibrillation patients using warfarin therapy. Epidemiol Biostatistics Public Health. 2018;15(1):

Supplementary material

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.