Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

Relationships Among Normative Beliefs About Aggression, Moral Disengagement, Self-Control and Bullying in Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Model

Authors Jiang H, Liang H, Zhou H, Zhang B

Received 12 November 2021

Accepted for publication 4 January 2022

Published 25 January 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 183—192

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S346658

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Huaibin Jiang,1 Hanyu Liang,1 Huiling Zhou,1 Bin Zhang2

1Department of Education, Fujian Normal University of Technology, Fuqing, Fujian, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Applied Psychology, Hunan University of Chinese Medicine, Changsha, Hunan, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Bin Zhang, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Adolescent bullying has varying degrees of negative impact on both bullies and victims. Bullying in adolescents is complex, and the influence of individual factors and social factors should not be underestimated. Normative beliefs about aggression play an important role in adolescents’ bullying. However, the mediating and moderating mechanisms underlying this association remain largely unknown. The current study investigated the mediating role of moral disengagement between normative beliefs about aggression and bullying, as well as the moderating role of self-control in this relationship from the perspective of individual cognition.

Methods: A sample of 491 Chinese adolescents (female = 38.9%; mean age = 13.05 years) were study participants. They completed questionnaires about normative beliefs about aggression, bullying, moral disengagement and self-control. SPSS21.0 statistical software was used to collate the obtained data, analyze descriptive statistics, and carry out reliability analysis and correlation analysis.

Results: Moral disengagement mediated the relationship between normative beliefs about aggression and bullying (ab=0.13, 95% CI=[0.07, 0.21]). The association between normative beliefs about aggression and moral disengagement was moderated by self-control (β=− 0.08, t=− 2.25, p< 0.05). The association between moral disengagement and bullying was moderated by self-control (β=− 0.09, t=− 2.42, p< 0.05).

Conclusion: Results revealed that moral disengagement mediates the link between normative beliefs about aggression and bullying. Self-control moderated the relationship between normative beliefs about aggression and moral disengagement, and between moral disengagement and bullying.

Keywords: normative beliefs about aggression, moral disengagement, self-control, bullying

Introduction

Bullying among teenagers is a common problem in the school environment in recent years. A survey of junior high school students by Chinese researchers found that 25.11% had been bullied.1 School bullying has become a major public health issue worldwide.2–4 Bullying, as a particular type of aggressive behavior, is a deliberate act by the bully to hurt the victim, and the victim tries to avoid it.5 As a serious adverse life event, bullying may cause short-term or long-term adverse effects on the academic development and mental health (depression, anxiety, suicide, etc.) of middle school students.6–9 Chinese researchers have proposed that the influencing factors of bullying can be divided into internal and external systems. The internal system refers to individual factors, including cognitive, emotional, personality and physiological factors.10 The external system refers to environmental factors, including family, peers, school and social norms.10–12 Therefore, the influence of social norms is considered in this study.

Normative beliefs about aggression are a kind of social norm acquired by individuals. It refers to the extent to which individuals believe that an aggressive response is an appropriate social behavior.13,14 In China’s traditional culture, some concepts affect people’s views on child violence, such as “spare the rod, spoil the child”, which may increase people’s tolerance towards violence.15 Consequently, it seems reasonable to assume that culture-driven positive appraisals of aggressive behavior might also be one factor influencing adolescents' bullying behavior. Relevant empirical studies also show that normative beliefs about aggression are positively correlated with bullying.16–18 Therefore, we consider the role of normative beliefs about aggressive behavior as a factor that could be relevant for the Chinese society. However, the mediating and moderating mechanisms underlying this association remain largely unknown.19,20

Moral Disengagement as a Mediator

Moral disengagement (MD) is a cognitive tendency of individuals to minimize their harm on others from immoral behaviours.21,22 Moral disengagement can help individuals reduce the tension they feel when they do not live up to their own moral standards and norms, such as bullying others. MD allows them to justify, rationalize, or reconstruct bullying. According to the general aggressive model (GAM), normative beliefs about aggression play a leading role in the causes of bullying.23 Normative beliefs about aggression will interfere with individuals’ moral cognition and lead to negative changes in individuals’ moral cognition and moral alienation, thus affecting the occurrence of bullying. Previous studies have shown that there is a significant correlation between normative beliefs about aggression and moral disengagement.24 Normative beliefs about aggression can weaken individual moral mechanisms and promote the rise of moral disengagement.25–27 Studies based on junior high school students in China also found that moral disengagement has a significant positive impact on aggressive behavior.28,29 Therefore, this study hypothesizes that moral disengagement is linked to normative beliefs about aggression and bullying.

Self-Control as a Moderator

Although normative beliefs about aggression may be linked with bullying through the mediating role of MD, not all individuals who are exposed to a high level of normative beliefs about aggression experience increased levels of bullying and show more MD. Therefore, it is important to explore those factors that may moderate the strength of the association among normative beliefs about aggression, MD and bullying. According to the self-control resource model, individuals who lack sufficient cognitive resources are more likely to choose aggressive behavior when facing unsatisfactory results.30,31 Inspired by this theory, we explored whether the link between normative beliefs about aggression and MD as well as between MD and bullying would be moderated by self-control.

Self-control refers to the ability of an individual conform to ideals, values, morals and social expectations.32 People with greater levels of self-control are more fair and trustworthy and tend to experience more guilt than other people.33 As a result, high self-control individuals should be less likely to experience increased levels of MD and activate bullying, and inhibit the promoting effect of normative beliefs about aggression on MD as well as MD on bullying. Empirical studies have supported that middle school students with low self-control levels are prone to cognitive impulse and are more likely to choose some socially unacceptable behaviors when trying to vent negative emotions.34 Since moral disengagement involves undesirable strategies that allow individuals to deviate from preferred social and moral standards, self-control can buffer moral disengagement.35 Studies have shown that the interaction term of moral disengagement and self-control may influence individual aggressive behavior.36,37

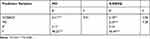

This study aimed to examine if normative beliefs about aggression influence bullying, taking into account moral disengagement and self-control. To address this problem, we hypothesized the following relationship with junior high school students: Hypothesis 1 stated that normative beliefs about aggression predicted bullying of junior high school students. Hypothesis 2 was that moral disengagement mediates the relationship between normative beliefs about aggression and bullying. Hypothesis 3 stated that the association between normative beliefs about aggression and moral disengagement is moderated by self-control. Hypothesis 4 was that the association between moral disengagement and bullying is moderated by self-control. Figure 1 presents the proposed the moderated mediation model.

|

Figure 1 Diagram of moderated mediation effect analysis. |

Methods

Participants and Procedure

This study was reviewed and approved by the Fujian Normal University of Technology Ethics Committee, and all methods were performed in accordance with government regulations, laboratory policies and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study as well as their custodians. In this study, 491 students from seven classes of grade 1st to grade 3rd in two middle schools in Fujian provinces were surveyed by a simple sampling method. The mean age of the subjects is 13.05 years (SD=0.85, range=12–15). Of these 491 students, 191 (38.9%) are female and 300 (61.1%) are male. Among them, 164 students (33.4%) are in the 1st grade, 162 students (33.0%) are in the 2nd grade, and 165 students (33.6%) are in the 3rd grade.

Measures

Normative Beliefs About Aggression Scale

The Chinese version of the NOBAGS was validated by Shao.38 NOBAGS is a 20-item measure of adolescents’ beliefs about the appropriateness of behaving aggressively. There were two dimensions: revenge attack belief (12 items) and general attack belief (8 items). This study used the belief subscale of general attack belief. Two sample items include “In general, it makes sense to use physical violence to take your anger out on someone else”, “When you are angry, it is not right to take it out on others”. The scale uses a 4-point score (1 corresponds to “completely disagrees”, and 4 corresponds to “completely agrees”). The higher the score is, the higher the participants’ belief level of the attack norm is, and the more they agree with the attack. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for scores for the NOBAGS was 0.73.

Moral Disengagement Questionnaire

The Chinese version of the MD was validated by Yang.21 MD is a 26-item scale measuring adolescents’ moral disengagement. The scale uses a 5-point score (1 corresponds to “completely disagrees”, and 5 corresponds to “completely agrees”). The scale includes 8 dimensions, including moral defense (eg, “There’s nothing wrong with fighting to protect a friend”), euphemistic labeling (eg, ”Talking about others behind their backs is just a joke”), favorable comparison (eg, ”Compared to people who cheat on exams, not studying hard is not a big deal”), responsibility shifting (eg, “If someone is forced to do something bad by a friend, he should not be blamed”), responsibility decentralization (eg, “A team collectively decided to do something bad, then it is not fair to blame any single member of them”), distorted results (eg, “Insults don’t hurt anyone”), blame attribution (eg, “People who are abused must have done something sorry to others”) and dehumanization (eg, “Some people should be treated inhumanly”). The higher the total score, the higher the moral disengagement level of the subjects. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for scores for the MD was 0.82.

Self-Control Scale

The Chinese version of the SCS was created by June.39 SCS is a 13-item measure of adolescents’ degree of self-control. The scale contains two dimensions: impulse control (nine items; eg, “I often act before I think it through”) and self-discipline control (four items; eg, “I can control my temper”). The scale uses a 4-point score (1 corresponds to “completely disagrees” and 4 corresponds to “completely agrees”). Responses to all items were lower scores indicating higher levels of self-control. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for scores from the SCS is 0.76.

Bully/Victim Questionnaire

The Chinese version of the R-OBVQ was validated by Zhang.40 R-OBVQ is a 6-item scale measuring adolescents’ bullying perpetration. A sample item was “I have kicked, hit, pushed, or bumped classmates”. The scale uses a 4-point score (1 corresponds to “completely disagrees” and 4 corresponds to “completely agrees”). The scale contains two sub-questionnaires, namely bullying and being bullied, which measure bullying status within 3 months. The higher the score, the more bullying. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for scores for the R-OBVQ was 0.74.

Procedure

After strict training by the psychology major graduate students as the experimenter, the questionnaires were conducted on a class-based basis. During the conducting process, the questionnaire requirements are disclosed to the subjects, and the questionnaire is collected and administered according to voluntary answers. A total of 491 valid questionnaires were collected with a recovery rate of 98.20%.

Data Analysis

SPSS21.0 statistical software was used to collate the obtained data and analyze descriptive statistics, as well as for reliability analysis and correlation analysis. Firstly, we computed descriptive statistics and conducted Pearson correlations to examine the relationships among normative beliefs about aggression, moral disengagement, self-control and bullying. Second, we examined whether moral disengagement mediated the relationship between normative beliefs about aggression and bullying using structural equation modeling (SEM). Specially, fit indices include R2 and F. Finally, we explored whether the mediation process was moderated by self-control using Hayes’s (2013) PROCESS macro (Model 59). Harman’s single factor test was used to investigate the common method bias. The result of single-factor test showed that the variation of the first-factor explanation was 15.32% (which was less than 40%).41 Therefore, the standard method bias effect was not significant in this study.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics and correlations were computed for all variables and are reported in Table 1. Normative beliefs about aggression were positively associated with bullying and moral disengagement (p<0.01), and negatively associated with self-control (p<0.01). Moral disengagement was positively correlated with bullying (p<0.01), and negatively correlated with self-control (p<0.01). There is a significantly negative correlation between self-control and bullying (p<0.01).

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Variables in the Whole Sample (N=491) |

Mediation Analysis: Moral Disengagement on Normative Beliefs About Aggression and Bullying

We examined moral disengagement as a mediator of the association between normative beliefs about aggression and bullying (H2). As Table 2 illustrates, multiple regression analysis indicated that normative beliefs about aggression significantly positively predicted bullying (β=0.18, p<0.01). Normative beliefs about aggression significantly positively predicted moral disengagement (β=0.41, p<0.01). Controlling for normative beliefs about aggression, moral disengagement significantly positively predicted bullying (β=0.33, p<0.001). The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method indicated that moral disengagement mediated the relationship between normative beliefs about aggression and bullying, ab=0.13, 95% CI=[0.07, 0.21]. The mediation effect accounted for 42.17% of the total effect. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 (moral disengagement mediates the relationship between normative beliefs about aggression and bullying) was supported.

|

Table 2 Summary Table of Mediation Effect Analysis (N=491) |

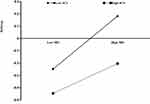

A Moderated Mediation Model: Normative Beliefs About Aggression, Moral Disengagement, Self-Control and Bullying

We examined self-control as a moderator on the associations between normative beliefs about aggression and bullying (Hypothesis 3), and between moral disengagement and bullying after controlling for normative beliefs about aggression (Hypothesis 4).41 Table 3 presents the evidence on the moderating role of self-control on the relationship between normative beliefs about aggression, moral disengagement and bullying.42 As Table 3 illustrates, the association between normative beliefs about aggression and moral disengagement was moderated by self-control (β=−0.08, t=−2.25, p<0.05). For descriptive purposes, this study plotted predicted moral disengagement against normative beliefs about aggression separately for low and high levels of self-control (1 SD below the mean and 1 SD above the mean, respectively) (Figure 2). Simple slope tests indicated that for individuals with low self-control (at 1 standard deviation), normative beliefs about aggression was strongly associated with moral disengagement. However, this association was weaker for individuals with high self-control (at −1 standard deviation). The relationship between moral disengagement and bullying was moderated by self-control (β=−0.09, t=−2.42, p<0.05). For descriptive purposes, this study plotted predicted moral disengagement against bullying separately for low and high levels of self-control (1 SD below the mean and 1 SD above the mean, respectively) (Figure 3). Simple slope tests indicated that for individuals with low self-control (at 1 standard deviation), moral disengagement was strongly associated with bullying. However, this association was weaker for individuals with high self-control (at −1 standard deviation).

|

Table 3 Summary of Moderated Mediation Effect Analysis (N=491) |

|

Figure 3 Moderation effect of self-control between moral disengagement and bullying. Abbreviations: NOBAGS, normative beliefs about aggression; MD, moral disengagement; SCS, self-control. |

Discussion

This study found that normative beliefs about aggression significantly predicted bullying by junior high school students. That is to say, normative beliefs about aggression could promote bullying by junior high school students. Junior high school students with firmer normative beliefs about aggression were more likely to have bullying. Consistent with the results, previous studies focusing on college students’ cyber-bullying also found that firm normative beliefs about aggression of college students will lead to more cyber-bullying, and firm normative beliefs about aggression will significantly positively influence adolescent bullying.18,43 Although more research is needed to investigate whether this link might be more pronounced in a Chinese population because of its parenting culture, the results suggest that studying these beliefs might prove important to understand the factors that underlie the development of aggressive behavior in Chinese adolescents.

This study found that moral disengagement played a partial mediating role in the influence of normative beliefs about aggression on junior high school students’ bullying. This is consistent with previous research results.19 This result also conforms to the general aggressive model theory,23 which provides a new theoretical perspective for explaining the internal influence mechanism of normative beliefs about aggression on junior high school students’ bullying. According to the GAM, when an individual produces aggressive behavior or bullying, the individual factor (the belief in the norms of aggressive behavior) will activate the individual’s internal information processing mode, and produce a hostile interpretation. This then interferes with the individual’s moral cognition level, leading to the deviation of the individual’s moral cognition. Adolescents with high normative beliefs about aggression will show a higher level of moral disengagement.23–27 Therefore, normative beliefs about aggression not only directly affect the bullying of junior high school students, but also indirectly affect the bullying through moral disengagement.

This study found that self-control played a moderating role in the relationship between normative beliefs about aggression and moral disengagement. Among low self-control adolescents, normative beliefs about aggression had a more significant effect on moral disengagement. A low self-control level strengthens the effect of normative beliefs about aggression on moral disengagement. Individuals with low self-control have a weak ability to resist temptation and regulate themselves. No matter whether the individual’s behavior is in line with their moral standards or whether the individual uses moral disengagement mechanism to rationalize immoral behavior, the individual’s self-control system is difficult to be activated. So the possibility of deviant behavior is very high.44 Adolescents with low self-control are prone to cognitive impulse, and, when trying to vent negative emotions, they are more likely to choose some socially unacceptable behaviors. Adolescents with high self-control are more likely to understand the harmful consequences of activating MD, so they may be unlikely to experience high MD.45

This study found that self-control played a moderating role in the relationship between moral disengagement and bullying. According to the theory of self-control resource model, individuals with strong self-control ability will make full use of cognitive resources to evaluate the suitability of possible aggression. Their behavior is more likely to be affected by personal values and social norms. Individuals with low self-control may lack in sense of personal agency and are prone to impulsive behavior and to engage in socially unacceptable behaviors. They are also at higher risk for ego-depletion or to experience energy decay. They are more susceptible to the influence of automatic attitude, which makes it difficult to invoke sufficient cognitive resources and timely cognitive monitoring of the aggressive behavior to be triggered. And this easily leads to the failure of the self-control process, and they may then attack others.46,47

Implications for Theory and Practice

Our findings have theoretical and practical contributions. In theory, this study explores the moderating role of self-control in normative beliefs about aggression and bullying, which has not been involved in previous studies and expands the overall research on aggression. In practice, it suggests that we should cultivate students’ self-control ability and reduce bullying behavior from the perspective of enhancing their own psychological quality.

Limitations and Prospects

There are also some shortcomings in this study, which provide directions for further research. First, this study is a cross-sectional study, so it is difficult to infer causality. Follow-up studies can use longitudinal design to investigate the relationship between normative beliefs about aggression, moral disengagement and bullying. Then they can look at the relationship between variables from a dynamic perspective (such as collecting data in three waves for testing mediation mode). Secondly, the self-report survey data are suspected of social desirability bias to the findings. Future studies should utilize both self-report and observational data for more definitive findings. Therefore, various ways (such as parent evaluation and peer evaluation, etc.) can be considered to obtain data in subsequent studies. Finally, although this study regards moral disengagement as a cognitive mechanism, previous studies have pointed out that moral disengagement can also be considered as a trait. Its regulatory agency can be studied by using moral disengagement as a moderating variable.25,48 Subsequent studies can investigate the moderating effect of moral disengagement on normative beliefs about aggression and bullying.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that normative beliefs about aggression not only directly increase the incidence of bullying, but also indirectly increase the risk of bullying through moral disengagement. Self-control moderated the relationship between normative beliefs about aggression and moral disengagement, as well as between moral disengagement and bullying.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in “figshare” at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.17427311.v1.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their useful comments on earlier drafts. We also want to thank Yongzhi Jiang, who gave us a lot of help in the revision of the article.

Funding

This research was supported by the Fujian Province Social Science Fund Project (Project number FJ2020B053) and the Research Foundation of Education Bureau of Hunan Province (Project number 21A0252).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Wang RN, Li R, Wang ZY, Liu QG. Campus bullying victimization and its influencing factors among middle school students in Dalian. Chin J Sch Health. 2021;42(10):1512–1515.

2. Arseneault L. The long-term impact of bullying victimization on mental health. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):27–28. doi:10.1002/wps.20399

3. Harris HK, Jong SC. Bullying victimization, school environment, and suicide ideation and plan: focusing on youth in low- and middle-income countries. J Adolesc Health. 2020;66(1). doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.07.006

4. Cash SJ, Bridge JA. Epidemiology of youth suicide and suicidal behavior. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21(5):613. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833063e1

5. Olweus D. Bullying at school. In: Aggressive Behavior: Current Perspectives. New York: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 1994:1171–1190.

6. Zhang Q. The performance analysis and future prospect of Chinese anti-bullying policy and practice: evidence from PISA 2015 and PISA 2018. Res Edu Dev. 2020;22:49–58. doi:10.14121/j.cnki.1008-3855.2020.22.008

7. Liu XQ, Yang MS, Peng C, Xie QH, Liu QW, Wu F. Anxiety emotion and depressive mood of middle school students with different roles in school bullying. Chin Ment Health J. 2021;35(6):475–481.

8. He WJ, Cai Y. Depressive symptoms and school bullying among middle school students in Bijie City. J Prev Med Info. 2021;37(4):539–552.

9. Li SY, Guo HB. Effects of discrimination and bullying on health risk behaviors of AIDS orphans: the mediating role of self- esteem. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2021;29(3):506–509.

10. Cao XL, Wen SY, Ke XY, Lu JP. Campus bullying in Shenzhen middle school students and its associations with quality of life. Chin J Sch Health. 2019;40(11):1679–1685. doi:10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2019.11.022

11. Hyun-Soo KH, Jongserl C. Bullying victimization, school environment, and suicide ideation and plan: focusing on youth in low- and middle-income countries. J Adolesc Health. 2021;66(1):115–122. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.07.006

12. Ye BJ, Yang Q. Temperament and parenting styles on adolescent aggression in adolescence: a test of interaction effects. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2012;20(5):484–687. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2012.05.017

13. Huesmann LR, Guerra NG. Children’s normative beliefs about aggression and aggressive behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;72(2):408–419. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.2.408

14. Van RL, Fischer TC, Zwirs BW. Social information processing mechanisms and victimization: a literature review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2016;17(1). doi:10.1177/1524838014557286

15. Wang XC, Yang JP, Wang PC, Lei L. Childhood maltreatment, moral disengagement, and adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration: fathers’ and mothers’ moral disengagement as moderators. Comput Human Behav. 2019;95:48–57. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.031

16. Krahé B, Busching R. Interplay of normative beliefs and behavior in developmental patterns of physical and relational aggression in adolescence: a four-wave longitudinal study. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1146. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01146

17. Padmanabhanunni A, Gerhardt M. Normative beliefs as predictors of physical, non-physical and relational aggression among South African adolescents. J Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2019;31:1–11. doi:10.2989/17280583.2019.1579096

18. Li JB, Nie YG, Boardley ID, Dou K, Situ QM. When do normative beliefs about aggression predict aggressive behavior? An application of 13 theory. Aggress Behav. 2015;41(6):544. doi:10.1002/ab.21594

19. Zheng Q, Bao YE, Yao YM, Chen JW, Hao FU, Lei BX. Normative beliefs about aggression on cyber-bullying: a chain mediating model. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2017;25(004):727–730. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2017.04.029

20. Lv SP, Shao R, Guo BY, Wang YQ. The impact of the family environment on adolescents’ aggression: the chain mediating effect of violent video games and normative beliefs about aggression. Chin J Special Educ. 2019;225(03):85–91.

21. Yang JP, Wang XC, Gao L. Concept, measurement and related variables of moral disengagement. Adv Psychol Sci. 2010;18(4):671–678. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1142.2010.40521

22. Bandura A. Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 1999;3(3):193–209. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3

23. Dewall CN, Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. The general aggression model: theoretical extensions to violence. Psychol Violence. 2011;1(3):245–258. doi:10.1037/a0023842

24. Paciello M, Fida R, Tramontano C, Lupinetti C, Caprara GV. Stability and change of moral disengagement and its impact on aggression and violence in late adolescence. Child Dev. 2008;79(5):1288–1309. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01189.x

25. Fang J, Wang X. Association between callous-unemotional traits and cyber-bullying in college students: the moderating effect of moral disengagement. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2020;28(2):281–284. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2020.02.013

26. Liu HP, Liu CS. Influence of college students’ network social support on network bullying: the mediating effect of moral evasion. China J Health Psychol. 2020;28(8):1263–1268. doi:10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2020.08.032

27. Wu P, Wang Y, Chun Z, Liu HS. Suppression-induced forgetting: the effects of suppression parameters, valence and arousal of experimental materials, anticipatory effect and individual differences. J Psychol Sci. 2019;42(5):1098–1105.

28. Desen MA, Jiao Z. Effect of moral disengagement on bullying of adolescents in campus PE: the moderated mediation model. J Tianjin Univ Sport. 2019;34(1):80–85. doi:10.13297/j.cnki.issn1005-0000.2019.01.012

29. Zhao WG, Wang YD, Jiang WN, Li XH. Deviant peer affiliation and male juvenile offenders aggressive behavior: a moderated mediation model. Chin J Special Educ. 2020;11:62–69.

30. Carver CS, Scheier MF. Origins and functions of positive and negative affect: a control-process view. Psychol Rev. 1990;97(1):19–35. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.97.1.19

31. Denson TF, DeWall CN, Finkel EJ. Self-control and aggression. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2012;21(1):20–25. doi:10.1177/0963721411429451

32. Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Tice DM. The strength model of self-control. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16:351–355. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00534.x

33. Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL. High self‐control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J Pers. 2004;72(2):271–324. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x

34. Liu XS, Mo L, Li D, Fu R. Extroversion and aggressive behavior in early childhood: moderating effects of self-control and maternal warmth. Psychol Dev Educ. 2020;36(5):538–544.

35. Valerie A. The role of social worldviews and self-control in moral disengagement. Pers Individ Dif. 2019;143. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2019.02.012

36. Shao R, Wang YQ. Reliability and validity of normative beliefs about aggression scale among middle school students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2017;25(6):1035–1038.

37. Li JB, Nie YG, Boardley ID, Situ QM, Dou K. Moral disengagement moderates the predicted effect of trait self-control on self-reported aggression. Asian J Soc Psychol. 2014;17(4):312–318. doi:10.1111/ajsp.12072

38. Osgood JM, Muraven M. Does counting to ten increase or decrease aggression? The role of state self-control (ego-depletion) and consequences. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2016;46(2):105–113. doi:10.1111/jasp.12334

39. Zhang WX, Wu JF, Kevin J. Revised version of the Olweus child bullying questionnaire. Psychol Dev Educ. 1999;02:7–12. doi:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.1999.02.002

40. Podsakoff PM, Mackenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

41. Muller D, Judd CM, Yzerbyt VY. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;89(6):852–863. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852

42. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2013.

43. Lim SH, Ang RP. Relationship between boys’ normative beliefs about aggression and their physical, verbal, and indirect aggressive behaviors. Adolescence. 2009;44:175.

44. Zhang SS, Zhang Y, Shen T. Daily violence exposure and its impact on campus bullying among middle school students in Xinxiang. Chin J Sch Health. 2020;41(5):709–712. doi:10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2020.05.020

45. Zhang XC, Chu XW, Fan CY. Peer victimization and cyber-bullying: a mediating moderation model. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2019;27:148–152.

46. Ke G. The strength model of self-control: evidence, controversies and prospect. Psychol Explor. 2012;2:45.

47. Geng YG, Sun QB, Huang JY, Zhu YZ, Han XH, et al. Effect of cyber victimization on deviant behavior in adolescents: the moderating effect of self-control. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2015;23(5):896–900. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2015.05.032

48. Jin TL, Lu GZ, Zhang L, Jin XZ, Wang XY. The effect of trait anger on online aggressive behavior of college students: the role of moral disengagement. Psychol Dev Educ. 2017;33(05):605–613. doi:10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2017.05.11

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.