Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 16

Relationship Between Mental Health Education Competency and Interpersonal Trust Among College Counselors: The Mediating Role of Neuroticism

Received 1 November 2022

Accepted for publication 30 December 2022

Published 19 January 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 169—177

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S389504

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Dan Li,1 Xiting Ma,2 Liang Chen3

1School of Humanities and Social Science, Beihang University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; 2Positive Psychology Experience Center, Beihang University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; 3School of Marxism, University of Science and Technology Liaoning, Anshan, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Liang Chen, Email [email protected]

Objective: Based on the motivated cognition account, this study aimed to explore the relationship between mental health education competency and interpersonal trust among college counselors, as well as the mediating effect of neuroticism.

Materials and Methods: A total of 483 college counselors were selected, including 155 men and 328 women. The youngest college counselor was 22 years old and the oldest was 56 years old (M = 31.69, SD = 6.12). The college counselors were asked to fill out the Mental Health Education Competency Scale for College Counselors, a 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory, and an Interpersonal Trust Scale.

Results: (1) This study found a significantly positive correlation between mental health education competency and interpersonal trust. (2) Mental health education competency and interpersonal trust were negatively correlated with neuroticism. (3) The mediating role of neuroticism in the association between mental health education competency and interpersonal trust was significant.

Conclusion: Mental health education competency partly affected interpersonal trust via the mediating effect of neuroticism.

Keywords: college counselors, interpersonal trust, mental health education competency, mediating effect, neuroticism

Introduction

In recent years, college students experience psychological issues frequently, which adversely affect their health and well-being. Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, college students experience different degrees of anxiety and depression. According to the National Mental Health Development Report of China (2019–2020), a survey of 8447 college students across the country found that although the overall mental health status of college students was good, a certain proportion of depression, anxiety, and other related issues should not be ignored. The results showed that 18.5% of college students were prone to depression, 4.2% were at high risk of depression, and 8.4% had an anxiety tendency.1 Zhu et al surveyed 15,936 college students about their psychological status in April 2020. They found depression and anxiety symptoms in 30.7% and 23.9% of students, respectively.2 Mental health education is an effective way to improve the mental health level of college students and promote their overall physical and mental health. It is also an important task for counselors.

The counselor system is a feature of Chinese higher education. As an important team engaged in education in college, counselors not only undertake ideological and political education but also provide psychological health education for college students. Moreover, counselors also deal with almost all types of affairs in students’ growth in colleges. The interpersonal trust of counselors with college students can promote the interaction between them and enhance the initiative and enthusiasm of counselors’ work. On the contrary, the lack of interpersonal trust will destroy the interpersonal relationship, and even cause loss and injury to both parties.3 Therefore, improving the level of interpersonal trust is conducive to further enriching the professional connotation of counselors’ work and enhancing the social identity of counselors’ profession. It is also an inevitable requirement to implement the fundamental task of college students’ mental health education and an objective need to promote the all-round development of students. Due to the importance of interpersonal trust, the mechanism of interpersonal trust and its influencing factors have attracted extensive attention from researchers across disciplines.4–6

A recent line of theoretical and empirical research has shown that a range of factors can influence interpersonal trust such as social class,7 social identity complexity,8 peer relationships,9 and emotion.10 However, although interpersonal trust is influenced by various correlates, research is yet to explore the relationship between competency and personality traits for interpersonal trust. To bridge this knowledge gap about interpersonal trust, the current study assesses whether neuroticism mediates the association between mental health education competency and interpersonal trust among college counselors.

Relationship Between Mental Health Education Competency and Interpersonal Trust

The mental health education competency of counselors is an important indicator of their competence in this work. Mental health education competency refers to the individual professional knowledge, professional skills, professional attitudes, or values in carrying out effective mental health education, including psychological problem identification, in-depth counseling intervention, caring for students, and self-efficacy.11 Psychological problem identification refers to the ability of counselors to observe and judge the nature and severity of students’ psychological problems, including three factors: theoretical basis, practical knowledge, and judgment. In-depth counseling intervention refers to counselors’ effective expression, communication, and resource integration to help students cope with psychological problems such as expression communication and resource collaboration. Caring for students refers to guidance from counselors who have a professional identity and sense of accomplishment, and who actively provide humanistic care and psychological counseling for students, including listening, responsibility identification, tolerance. Self-efficacy refers to a counselor’s subjective speculation and judgment about whether they will succeed in mental health education.11

Interpersonal trust refers to a willingness to accept risks assuming that others’ intentions and behavior are positive.12 Interpersonal trust is an important aspect of human life,13 which plays an important role in building harmonious interpersonal relationships.14 The motivated cognition account holds that individuals tend to perceive their expected facts as facts when making trust decisions to alleviate their own cognitive dissonance.15 For example, the truster’s motivation to expect others to be trustworthy will promote the truster’s perception of the others to be trustworthy, and then make the decision to trust the others more easily. Mutual trust is a prerequisite for the good effect of mental health education. In mental health education, counselors tend to choose emotion-centered education, pay attention to long-term emotional communication, and pay more attention to the effect of education rather than profit return. In essence, the trust relationship is also a social exchange relationship; therefore, the social exchange motivation of the truster may affect his trust cognition and then affect his interpersonal trust level. We hypothesized that counselors with a high level of mental health education competency were more likely to trust college students than counselors with a low level of mental health education competency because of their strong motivation for social–emotional exchange to improve the educational effect. Moreover, it was found that the entrepreneurial competency and management competency of entrepreneurs could help to improve the cognitive trust of the other entrepreneurial team members, while the social competency of entrepreneurs, including social perception and social adaptability, could promote the development of emotional trust to the other entrepreneurial team members.16 Therefore, this study hypothesized that the mental health education competency of counselors has a positive predictive effect on interpersonal trust.

Mediating Effect of Neuroticism

Many factors predict interpersonal trust, among which personality traits are an important factor.17 First, personality traits can predict trust responses.18 For example, people with low trait forgiveness tendency have lower trust in defaulters who are forced to make compensatory behaviors.19 Personality traits such as agreeableness and honesty–humility can predict trust behaviors in trust games.18 Second, personality traits can predict interpersonal trust tendency. For example, extraversion and agreeableness, responsibility, and openness can positively predict interpersonal trust tendency.19,20 Neuroticism,19–21 machiavellianism, and psychopathy dimensions of dark personality have a direct negative predictive effect on interpersonal trust.22 Relatively few studies exist on the relationship between personality traits and individual competency. A previous study found that perceived competency with social skills involved in initiating relationships and providing emotional support was negatively correlated with neuroticism.23 But neuroticism was not identified as an information competency among college students.24 These inconsistent results might be due to the type of competence, that is, neuroticism is negatively correlated with competence about interpersonal contexts. When engaging in mental health education, college counselors with a high level of neuroticism are often manifested with emotional instability, emotional impulsiveness, anxiety, and so on. It is difficult to experience students’ situations without being in their own shoes and without empathizing with the emotions of others. Neuroticism will also affect counselors’ use of relevant psychological counseling techniques to carry out mental health education. Therefore, this study hypothesized that neuroticism plays a mediating role in the association between mental health education competency and interpersonal trust.

Present Study

Although previous studies have found that individual competency is positively correlated with interpersonal trust, the relationship between specific competency and interpersonal trust and their psychological mechanisms is rarely discussed. Based on the intervention practice of mental health education for college students, the present study aimed to investigate the mediating role of negative personality traits in the relationship between mental health education competency and interpersonal trust of counselors so as to provide theoretical support and empirical basis for formulating effective training programs for mental health education competency of counselors.

Materials and Methods

Participants

A stratified cluster random sampling method was used to select seven universities in Beijing, including three national key universities and four general universities. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic’s prevention and control policies, the informed consent and questionnaire were published on the professional questionnaire survey platform named “Wenjuanxing” (www.wjx.cn). In January 2022, researchers posted the online link of the website to the counselor network groups. Then, college counselors were invited to participate in the survey to collect data. Finally, 496 questionnaires were recovered. Because the options filled in the questionnaire were the same or regular, 13 invalid questionnaires were removed, and 483 valid samples were finally obtained. The number of counselors in the 7 colleges was about 2100, and the participation rate was 18.4%. Out of the 483 questionnaires, 155 were of men (32.1%) and 328 were of women (67.9%). Further, 7 counselors had a bachelor’s degree, 468 had a master’s degree, and 8 had a doctor’s degree. The age of the subjects ranged from 22 to 56 years, with an average age of 31.69 years and a standard deviation of 6.12.

This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines, and the study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Beihang University. All participants provided online informed consent before they participated in the study.

Measures

Mental Health Education Competency

The Mental Health Education Competency Scale for College Counselors was compiled by Li and Ma.11 The scale includes psychological problem identification, in-depth counseling intervention, caring for students, and self-efficacy. A total of 30 items were included in the 5-point Likert-type method, from “no” to “always.” The higher the total score, the stronger the participants’ mental health education competency. In this study, the internal consistency reliability coefficient of the total scale was 0.975, and the internal consistency reliability coefficients of the four subscales of psychological problem identification, in-depth counseling intervention, caring for students, and self-efficacy were 0.959, 0.926, 0.953, and 0.954, respectively. The confirmatory factor analysis showed that the questionnaire structure was acceptable (χ²/df = 8.203***comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.970, TLI = 0.909, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.025, RSMER = 0.206).

Neuroticism

Rammstedt and John developed a 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory.25 The scale contains neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness. Each subscale contains two items. All items adopt a Likert 5-point type (1 means “strongly disagree” and 5 means “strongly agree”). The goodness-of-fit indices (χ²/df = 45.94***CFI = 0.981, TLI = 0.963, SRMR = 0.024, RSMER = 0.059) were good, indicating that the questionnaire has good structural validity. The neuroticism subscale was used in this study, and the internal consistency reliability coefficient of the questionnaire was 0.513.

Interpersonal Trust

The Interpersonal Trust Scale was developed by Rotter to predict estimates of the reliability of behavioral commitments or statements made by others.26 A total of 25 items are included in this Interpersonal Trust Scale in a variety of situations involving different social roles including parents, salesmen, general population, politicians, and the media. The scale contains two factors: one is trust in peers or other family members, and the other is trust in strangers, with Likert 5-point scoring (1 means “strongly disagree” and 5 means “strongly agree”). This study mainly examined the interpersonal trust of counselors with students. According to the revision procedure of the questionnaire,27 questions 5, 6, 18, 22, and 25 were selected, and the parents in item 6 and the people in item 25 were replaced by college students. A psychology professor and 10 college counselors were invited to assess the clarity of the questionnaire. Finally, the counselor–student Interpersonal Trust Scale was formed. The internal consistency reliability coefficient of the scale was 0.896. The confirmatory factor analysis supported the one-factor model (χ²/ df = 8.203***CFI = 0.975, TLI = 0.949, SRMR = 0.030, RSMER = 0.132).

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 23.0 and Mplus 8.3 were used for data management and analysis, including correlation analysis, reliability analysis, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and structural equation model (SEM). First, reliability analysis and CFA were used to examine the reliability and validity of scales, respectively. Next, frequency and descriptive statistics were applied to examine the mean scores, standard deviations, and skewness–kurtosis values of the variables. Then, Pearson’s correlation was used to calculate the correlation coefficients among variables. Finally, SEM was used with the nonparametric percentile bootstrap method and 95% confidence intervals to test the hypothesized mediation model. Several goodness-of-fit indices were selected: the chi-squared goodness-of-fit statistic, the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), the CFI, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the SRMR. TLI and CFI values higher than 0.90 indicated an acceptable fit. A value of less than 0.08 or lower for RMSEA and SRMR implied a moderate fit.28

Results

Descriptive Characteristics and Correlation Analysis Among Variables

The demographic characteristics of the study’s participants are depicted in Table 1. The results of correlation analysis showed the counselors’ mental health education competency and its four dimensions, and neuroticism and interpersonal trust were significantly correlated (see Table 2). Among these, counselors’ mental health education competency and its four dimensions were negatively correlated with neuroticism (r = –0.242 to –0.382, p < 0.01) and positively correlated with interpersonal trust (r = 0.383 to 0.466, p < 0.01). Neuroticism was negatively correlated with interpersonal trust (r = −0.28, p < 0.01).

|

Table 1 Descriptive Characteristics of the Sample |

|

Table 2 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Variables (N = 483) |

Mediating Effect Analysis

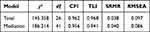

Since counselors’ mental health education competency, neuroticism, and interpersonal trust are all latent variables, an SEM should be established. In this study, nonparametric percentile bootstrap estimation with bias correction was used to test the mediating effect of neuroticism in the relationship between mental health education competency and interpersonal trust of counselors, and all variables were standardized (STDYX Standardization). First, the total effect model of mental health education competency of counselors on interpersonal trust was established, and the total effect and its significance were tested. The results showed that the total effect of the mental health education competency of counselors on interpersonal trust was 0.483, and the total effect coefficient was significant (p < 0.001). Except for RMSEA, all the fitting indicators were generally good (see Table 3).

|

Table 3 Total Effect Model and Mediation Model Fit Index |

Second, the significance of the path coefficients was tested sequentially. In this study, a mediation model was established with counselors’ mental health education competency as the independent variable, interpersonal trust as the dependent variable, and neuroticism as the mediating variable (see Figure 1). The SEM analysis showed that all the fit indices except RMSEA were good (see Table 3), indicating that the model was acceptable.

Third, the 95% confidence intervals of the path coefficients were estimated, and the sampling was repeated 1000 times. The results showed that the confidence interval of the standardized indirect effect from counselors’ mental health education competency to neuroticism to interpersonal trust was 0.006 and 0.134, excluding 0, and the indirect effect was 0.107, accounting for 22.245% of the total effect.

Discussion

A Direct Effect of Counselors’ Mental Health Education Competency on Interpersonal Trust

It was found that the competency of counselors in mental health education had a significant positive effect on the interpersonal trust between counselors and college students, that is, the higher the competency level, the stronger the counselors’ trust in college students. Interpersonal trust—individuals’ confidence that they will not take advantage of each other’s weaknesses and their positive expectations for each other’s behavior in the process of communication—will be affected by interpersonal relationships and play a role in individual behavior activities.29 Interpersonal relationship—the connection formed by communication between individuals and others—can be divided into two subtypes based on its establishment: affective relationship for the purpose of emotional exchange and instrumental relationship for the purpose of economic interest exchange.30 Affective relationship is an emotional connection established based on an emotional expectation of others, which can effectively increase the trust of both parties.31 On the contrary, an instrumental relationship focuses on the benefit-based relationship with others, and compared with utilitarianism, it will reduce the individual’s trust in others.28 In mental health education, counselors tend to choose emotion-centered education, pay attention to long-term emotional communication, and pay more attention to the effect of education rather than to profit. Therefore, the relationship between counselors and students is a kind of affective relationship. Counselors with a higher level of mental health education competence can make in-depth observations and accurate judgments about the nature and severity of psychological problems of students via effective expression and communication and resource integration to help college students cope with psychological perplexity.

According to the motivated cognition account,15 individuals tend to perceive their expected facts as facts when making trust decisions to alleviate their own cognitive dissonance. When counselors make trust decisions for college students, counselors with higher competence have stronger motivation and self-efficacy to care for students and tend to expect more effective mental health education; therefore, the interpersonal trust degree is stronger. Other research shows that trustworthiness factors such as competence, integrity, and kindness are related to the establishment of interpersonal trust between counselors and clients, while the lack of competency-related trustworthiness cannot be compensated by others.32 At the beginning of building a counseling relationship,33 counselors would judge the contents of college students’ confessions. Influenced by the defense mechanism,34 college students’ statements are not comprehensive or in-depth. Counselors with higher mental health education competency levels will make a correct judgment on the confessions of college students by using years of consulting experience and psychological counseling techniques so as to make positive responses and promote the healthy development of consulting relationships. On the contrary, counselors with lower mental health education competency levels may doubt the content or misunderstand the intention of college students, thus making a negative response and reducing interpersonal trust. Therefore, counselors with higher levels of mental health education competence have better interactive relationships with students, stronger emotional relationships, and higher trust levels.

Mediating Effect of Neuroticism

This study found that neuroticism played a mediating role in the relationship between mental health education competency and interpersonal trust among college counselors. This result was consistent with Ye’s study, which found that people who were higher in agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness, but lower in extraversion and neuroticism, preferred to work as psychological counselors.35 An excellent mental health educator needs to have some stable psychological traits, such as positive personality traits, cognitive flexibility, and emotional regulation ability.36 Neuroticism is a dimensional measure of emotional stability and sensitivity to negative information in personality structure. Individuals with higher levels of neuroticism may not respond well to stressors, are more emotional than others, have difficulty controlling impulses and delaying gratification, and are likely to interpret ordinary situations as threatening or difficult, as compared to norm groups.37 Therefore, counselors with high neurotic levels often feel anxious in the process of objectively analyzing and understanding students’ psychological and realistic conditions and are prone to emotional instability, emotional impulse, and other problems. It is difficult to properly deal with their own psychological conflicts, and they cannot carry out good self-psychological adjustment, thus affecting the effect of mental health education.

Studies have shown that individuals with negative personality traits not only have lower emotional and higher instrumental relationships with others but also have difficulty in establishing a good sense of trust with et al.38 Individuals with a high level of negative traits generally adopt a fast-life strategy, do not consider long-term interests and do not invest too much emotion, and establish a less emotional connection and more utilitarian interpersonal relationships with others.38 However, individuals with low emotional connections are less likely to have trust in others.31 Moreover, the mood-congruence hypothesis holds that when encoding and extracting current information, individuals will be more sensitive to the part that is consistent with the current emotional information.39 Negative emotions lead individuals to make more negative judgments about others and social events, thus reducing their trust in others. For example, negative emotions such as anger and sadness will reduce interpersonal trust.10 Individuals with high levels of neuroticism are more likely to experience negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, guilt, and depression. Therefore, counselors with high levels of neuroticism have low interpersonal trust in college students.

Limitations and Implications

This study had several shortcomings. First, a self-assessment questionnaire was used in this study. The validity of the research conclusions can be improved by combining other evaluation questionnaires and experimental methods in the future. Second, the study samples were mainly from undergraduate students. Counselors can be selected from graduate and doctoral levels in future studies to further expand the representation of the sample. Third, the internal consistency of neuroticism was lower in this study. Future studies can use other scales to measure neuroticism, such as Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. Finally, a cross-sectional study was conducted. Future studies can be combined with longitudinal follow-up studies to further validate the findings.

Conclusions

The present study used a mediating model to examine the relationship between mental health education competency and interpersonal trust among college counselors. It was found that neuroticism served a mediating role in the relationship between mental health education competency and interpersonal trust among college counselors.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by Ideological Department of Ministry of Education and Higher Education Press through an Entrusted Project “Cultivating Courses for College Counselor Mental Education Competencies”, and also provided by Beijing Municipal Commission of Education through a Research Project “Research and Practice in Ma Xiting Mental Assistance Studio”(31700002021111002).

Disclosure

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Fu XL, Zhang K. China National Health Development Report (2019–2020). Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press; 2021:98–100.

2. Zhu ZY, Zhang Y, Gan H, Tao SM, Tao FB, Wu XY. The association between depressive and anxiety symptoms and COVID-19 risk perception among college students. Chin Health Edu. 2022;2:145–149.

3. Ben-Ner A, Halldorsson F. Trusting and trustworthiness: what are they, how to measure them, and what affects them. J Eco Psychol. 2010;31(1):64–79. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2009.10.001

4. McEvily B, Tortoriello M. Measuring trust in organizational research: review and recommendations. J Trust Res. 2011;1:23–63. doi:10.1080/21515581.2011.552424

5. Schoorman FD, Mayer RC, Davis JH. An integrative model of organizational trust: past, present, and future. Acad Manage Rev. 2007;32:344–354. doi:10.5465/amr.2007.24348410

6. Wang P, Liang Y, Li Y, Liu YH. The effects of characteristic perception and relationship perception on interpersonal trust. Advances Psychol Sci. 2016;24:815–823. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2016.00815

7. Samson K, Zaleskiewicz T. Social class and interpersonal trust: partner’s warmth, external threats and interpretations of trust betrayal. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2020;50:634–645. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2648

8. Xin S, Xin Z, Lin C. Effects of trustors’ social identity complexity on interpersonal and intergroup trust. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2016;46:428–440. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2156

9. Wang G, Hu W. Peer relationships and college students’ cooperative tendencies: roles of interpersonal trust and social value orientation. Front Psychol. 2021;12:656412.

10. Dunn JR, Schweitzer ME. Feeling and believing: the influence of emotion on trust. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;88:736–748. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.5.736

11. Li D, Ma XT. Research on mental health Education competency of college counselors. School Party Build Ideol Edu. 2022;669:6–9.

12. Rousseau DM, Sitkin SB, Burt RS, Camerer C. Not so different after all: a cross-discipline view of trust. Acad Manage Rev. 1998;23:393–404. doi:10.5465/amr.1998.926617

13. Hooghe M, Marien S, de Vroome T. The cognitive basis of trust. The relation between education, cognitive ability, and generalized and political trust. Intelligence. 2022;40:604–613. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2012.08.006

14. Rghett F, Finkenaue C. If you are able to control yourself, I will trust you: the role of perceived self-control in interpersonal trust. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;100:874–886. doi:10.1037/a0021827

15. Weber JM, Malhotra D, Murnighan JK. Normal acts of irrational trust: motivated attributions and the trust development process. Res Organ Behav. 2004;26:75–101.

16. Pan QQ, Wei HM. The relationship between founder competency and entrepreneurial team members’ trust under different stages of new venture. Sci Tech Prog Pol. 2016;33:7.

17. Thielmann I, Hilbig BE. Trust in me, trust in you: a social projection account of the link between personality, cooperativeness, and trustworthiness expectations. J Res Pers. 2014;50:61–65. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2014.03.006

18. Zhao K, Smillie LD. The role of interpersonal traits in social decision making: exploring sources of behavioral heterogeneity in economic games. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2015;19:277–302. doi:10.1177/1088868314553709

19. Desmet PTM, De Cremer D, van Dijk E. Trust recovery following voluntary or forced financial compensations in the trust game: the role of trait forgiveness. Pes Indiv Differ. 2011;51:267–273. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.027

20. Xu F, Li H, Ma F. The relationship between trust tendency and personality traits of college students. J Appl Psychol. 2011;17:202–211.

21. Evans AM, Revelle W. Survey and behavioral measurements of interpersonal trust. J Res Pers. 2008;42:1585–1593. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2008.07.011

22. Dong Y, Wang HF, He YX, Zhang DH. Dark triad and adolescents’ interpersonal trust: the mediating role of ostracism. Psychol Tech Appl. 2020;8:7.

23. Jenkins-Guarnieri MA, Wright SL, Hudiburgh LM. The relationships among attachment style, personality traits, interpersonal competency, and Facebook use. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2012;33:294–301.

24. Kwon N, Song H. Personality traits, gender, and information competency among college students. Malays J Libr Inf Sc. 2011;16:87–107.

25. Rammstedt B, John OP. Measuring personality in one minute or less: a 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. J Res Pers. 2007;41:203–212. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001

26. Rotter JB. A new scale for measurement of interpersonal trust. J Res Pers. 1967;35:651. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1967.tb01454.x

27. Hambleton RK, Kanjee A. Increasing the validity of cross-cultural assessments: use of improved methods for test adaptations. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2001;17(3):147–157.

28. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to under parameterized model misspecification. Psychol Methods. 1998;3:424–453. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

29. García-Sánchez P, Díaz-Díaz NL, De Saá-pérez P. Social capital and knowledge sharing in academic research teams. Int Rev Adm Sci. 2019;85:191–207. doi:10.1177/0020852316689140

30. Chua RYJ, Morris MW, Ingram P. Guanxi vs networking: distinctive configurations of affect- and cognition-based trust in the networks of Chinese vs American managers. J Int Bus Stud. 2009;40:490–508. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400422

31. Li XC, Liu L. Embedded guanxi networks, market guanxi networks and entrepreneurial growth in the Chinese context. Front Bus Res China. 2021;4:341–359. doi:10.1007/s11782-010-0101-4

32. Mauerer C. The Development of interpersonal trust between the consultant and client in the course of the consulting process. In: Nissen V, editor. Advances in Consulting Research. Contributions to Management Science. Springer, Cham; 2019.

33. Sexton TL, Whiston SC. The status of the counseling relationship: an empirical review, theoretical implications, and research directions. Coun Psychol. 1994;22:6–78. doi:10.1177/0011000094221002

34. Cramer P. Coping and defense mechanisms: what’s the difference? J Pers. 2002;2002(66):919–946.

35. Ye L, Wu M, Wang X, Li Z, Wu MS. Psychological counselors’ self: an ecological recognition of big five personality traits based on column blogs in China. Hum Behav Emerg Technol. 2019;1:223–228. doi:10.1002/hbe2.164

36. Ferah Ç. The relationships between the big five personality traits and attitudes towards seeking professional psychological help in mental health counselor candidates: mediating effect of cognitive flexibility. Educ Res Rev. 2019;2019(14):501–511. doi:10.5897/ERR2019.3706

37. Scandell DJ, Wlazelek BG, Scandell RS. Personality of the therapist and theoretical orientation. Irish J Psychol. 1997;18:413–418. doi:10.1080/03033910.1997.1010558161

38. O’Boyle E, Forsyth DR, Banks GC, McDaniel MA. A meta-analysis of the Dark Triad and work behavior: a social exchange perspective. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2021;97:557–579. doi:10.1037/a0025679

39. Winkielman P, Knutson B, Paulus M, Trujillo JL. Affective influence on judgments and decisions: moving towards core mechanisms. Rev Gen Psychol. 2007;11:179–192. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.11.2.179

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.