Back to Journals » Biologics: Targets and Therapy » Volume 13

Recurrent ruptured abdominal aneurysms in polyarteritis nodosa successfully treated with infliximab

Authors Lerkvaleekul B , Treepongkaruna S , Ruangwattanapaisarn N , Treesit T , Vilaiyuk S

Received 10 February 2019

Accepted for publication 9 May 2019

Published 14 June 2019 Volume 2019:13 Pages 111—116

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/BTT.S204726

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Doris Benbrook

Butsabong Lerkvaleekul,1 Suporn Treepongkaruna,2 Nichanan Ruangwattanapaisarn,3 Tharintorn Treesit,3 Soamarat Vilaiyuk1

1Division of Rheumatology, Department of Paediatrics, Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; 2Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Paediatrics, Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; 3Department of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Radiology, Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand

Abstract: Systemic polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a rare form of necrotizing vasculitis in children. Recurrent episodes of abdominal aneurysm ruptures are uncommon and life-threatening condition in children. Failures of response to immunosuppressive medications and radiological intervention also lead to high mortality. Some reports suggested that tumor necrosis factor (TNF) might have role in the inflammation of this disease. After an English-language literature review, this is the first case report in children of recurrent abdominal-ruptured aneurysms with a failure of conventional therapy but successfully treated with anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody. We herein describe a 9-year-old girl who presented with chronic abdominal pain, hypertension, and massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding. The disease was refractory to conventional treatment, including administration of a corticosteroid, cyclophosphamide, and intravenous immunoglobulin, and recurrent-ruptured aneurysms developed in the gastrointestinal tract. Arterial embolization during angiography resulted in temporary improvement of the gastrointestinal bleeding. Infliximab, a chimeric anti-tumor necrosis factor-α monoclonal antibody, was initiated and resulted in disease remission with resolution of the gastrointestinal bleeding and abdominal pain. Anti-TNF therapy might be another treatment option for refractory disease to prevent ongoing inflammation that could lead to aneurysmal dilatation or even rupture. However, early recognition of refractory disease and aggressive treatment in the early course of the disease are crucial to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: vasculitis, gastrointestinal bleeding, tumor necrosis factor, infliximab, biologic therapy

Introduction

Systemic polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a rare primary vasculitis syndrome affecting medium-sized arteries in various organs. Approximately 50% of the patients have gastrointestinal (GI) involvement with various pathologies including ischemia, infarction, and hemorrhage.1 Severe GI hemorrhage from multiple ruptures of aneurysms of arteries that supply the GI tract is rarely described. Although the pathophysiology remains unclear, some evidence suggests that tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α might play a role in the development of vasculitis.2 TNF-α, which is produced primarily by macrophage, can induce leukoendothelial adhesion and mediate neutrophil migration by its chemoattractant effect. In addition, TNF-α also synthesizes proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines and activates T and B lymphocyte cells.3,4 Histopathology showed that polymorphonuclear cells and lymphocyte cells infiltrate around vessel walls, leading to arterial wall inflammation, disruption, and fibrinoid necrosis, which is a typical feature of PAN. The inflammation may take place in the tunica intima, then progress to entire arterial wall, including internal and external elastic lamina.5 At that time, the inflammation of the vessels can weaken the arterial wall, resulting in aneurysmal dilatation and eventual rupture.6 Previous report also demonstrated the increased TNF-α gene expression in mononuclear cells from patients with PAN,2 leading to hypothesis that TNF-α may involve in the pathogenesis of PAN. Treatment of patient with PAN is usually based on corticosteroids and steroid-sparing drugs such as cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, and methotrexate. Infliximab, a chimeric anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody, has rarely been reported for treatment of childhood PAN. We herein describe a 9-year-old girl who developed recurrent severe lower GI bleeding from ruptured aneurysms of the GI tract requiring blood transfusion and selective arterial embolization. Her condition was unresponsive to a conventional treatment regimen but finally showed a clinical response to infliximab treatment.

Case report

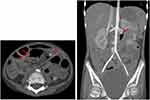

A 9-year-old girl was referred to our hospital with 3-month history of severe intermittent abdominal pain, hypertension, and renal infarction from computed tomography scan. She had a history of untreated left hemiparesis 2 years previously, and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed multiple old lacunar infarctions in the basal ganglion, left thalamus, midbrain, and pons. Magnetic resonance angiography of the brain showed no significant stenosis or aneurysm. On admission (day1 [D1]), she was fully conscious and mildly pale with a blood pressure of 160/100 mmHg, pulse rate of 99/min, body weight of 15 kg, and height of 123 cm. Abdominal examination revealed no distension, tenderness, or organomegaly. Neurological examination revealed left hemiparesis with a muscle strength of grade 4/5, positive clonus, and the Babinski sign on the left side; the findings were otherwise unremarkable. Laboratory examination revealed a hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL, white blood cell count of 7,600 cells/mm3 (neutrophils, 65%; lymphocytes, 25%; monocytes, 8%; eosinophils, 2%), platelet count of 290,000 cells/mm3, erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 79 mm/hr, C-reactive protein level of 77.6 mg/L, antistreptolysin O titre of 488.6 IU/mL, and normal urinalysis findings and liver and renal function. No evidence of hepatitis B infection was found. Antinuclear antibodies, cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), and perinuclear ANCA were negative. C3 and C4 were normal. Computed tomography angiography of the whole aorta showed multiple intra-abdominal aneurysms and intraparenchymal renal aneurysms (Figure 1). Systemic PAN was diagnosed based on the involvement of multiple medium-sized arteries. Three doses of pulse methylprednisolone followed by intravenous cyclophosphamide 500 mg/body surface area were given.

Antihypertensive medications were also prescribed, including atenolol, amlodipine, hydralazine, and nifedipine. The patient’s blood pressure was difficult to control because of her severe intermittent abdominal pain. She subsequently developed massive lower GI bleeding and hemorrhagic shock on D24 and was transferred to the intensive care unit. Blood components and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) 1 g/kg/dose for 2 days were given, but the GI bleeding continued. Emergency angiography showed ruptured jejunal arterial aneurysms, and selective arterial embolization was successfully performed (Figure 2). Three weeks later (D43), after a third dose of cyclophosphamide, she developed three recurrent episodes of severe lower GI bleeding; however, angiographic examination failed to demonstrate active contrast extravasation, and the bleeding was probably due to vasospasm.

Therefore, infliximab (a chimeric anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody) 100 mg (6.7 mg/kg/dose) was commenced at 0 (D99), 2, and 4 weeks, then every 4 weeks for 6 months along with the other supportive treatments shown in Figure 3. She responded well to the infliximab therapy without any side effects and was discharged from hospital on D166. At the 5-month follow-up visit, her symptoms were markedly improved. Her abdominal pain and hematochezia were resolved. Her blood pressure was controlled by atenolol and amlodipine. Her neurological signs and symptoms remained stable. Computed tomography angiography of the whole aorta revealed that some of the aneurysms had decreased in size (Figure 4). She was able to return to school and was satisfied with this treatment. After discontinuation of infliximab, azathioprine was started for long-term maintenance therapy. At the one-year follow-up visit, her disease was controllable with azathioprine and a low dose of a corticosteroid. She had no abdominal pain or GI blood loss, and her blood pressure was controlled with amlodipine and atenolol.

| Figure 3 Summary of hospital course in the present case.Abbreviations: Hb, hemoglobin; CRP, C-reactive protein; IVCY, intravenous cyclophosphamide; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; IFX, infliximab. |

This report was approved by the Ramathibodi Hospital Institutional Review Board, and the legal guardian of the patient provided written informed consent to have the case details published.

Discussion

This patient was diagnosed with PAN and developed recurrent abdominal aneurysm rupture due to active disease despite corticosteroid, IVIG, and cyclophosphamide therapy. PAN with ruptured aneurysms is a rare but life-threatening condition in children. Several studies have revealed high mortality rates of PAN in children who presented with acute abdomen despite the administration of combined medical and surgical treatment.7,8 Approximately 50% of the patients with systemic PAN have GI involvement ranging from mild to severe manifestations.1 The most common symptom is abdominal pain; others include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and GI bleeding. Approximately 30% of the patients with systemic PAN require surgery for acute abdomen caused by peritonitis, bowel perforation, bowel ischemia/infarction, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, or appendicitis. Severe GI bleeding from ruptured aneurysms of the GI tract is a rare presentation with a poor prognosis.1,9 Aneurysms are caused by weakening of the vessel walls secondary to an ongoing inflammatory process in which polymorphonuclear leucocytes and antigen–antibody complexes are deposited in the vessel walls. Timely diagnosis and aggressive treatment are keys to a successful outcome. Previous studies have revealed aneurysm regression and even complete resolution in patients who respond to treatment.10 In the present study, we reviewed the English-language literature of pediatric patients with PAN characterized by bleeding from ruptured aneurysms of arteries supplying the GI tract (Table 1). The most common site of a ruptured aneurysm in such patients is the superior mesenteric artery, mainly the jejunal branch. The most common symptoms are abdominal pain and GI bleeding. Appropriate timing of embolization or surgical intervention is crucial in cases of severe bleeding.

| Table 1 Cases of pediatric PAN with bleeding from ruptured aneurysms of arteries supplying the GI tract |

Induction therapy of PAN is usually based on a combination of a corticosteroid and cyclophosphamide followed by maintenance therapy with either azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil.11 Other treatments for refractory PAN include IVIG, plasma exchange, infliximab, and rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody). A few reports have described pediatric patients with PAN and GI involvement who were successfully treated with infliximab at 3 to 6 mg/kg/dose.12 The indications for infliximab in these reports were PAN refractory to conventional therapy or PAN with life-threatening organ involvement such as cerebral vasculitis, interstitial lung disease, or pulmonary hypertension. GI involvement in these case reports was characterized by abdominal pain, intestinal inflammation, or vasculitis.12,13 Failed conventional therapies included azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, IVIG, cyclosporine A, and methotrexate. Along with infliximab, some patients also received concomitant immunosuppressive drugs such as azathioprine, methotrexate, or cyclophosphamide. One case report described a patient who developed cerebral abscesses following two doses of infliximab and one dose of cyclophosphamide. Other reports described infectious complications including urinary tract infection, shingles, and sepsis.12

Studies on infliximab therapy for pediatric patients with PAN and multiple aneurysms are limited. Our patient was refractory to treatment with a corticosteroid, intravenous cyclophosphamide, and IVIG but had a dramatic clinical response to infliximab treatment, resulting in resolution of the GI bleeding and abdominal pain. Moreover, imaging showed that the aneurysms decreased in size. Our findings suggest that infliximab can be used to achieve remission and prevent complications from abdominal aneurysm ruptures in childhood PAN. Additionally, the findings in this case indicate that TNF-α may have an important role in the pathogenesis of PAN. However, we cannot conclude that infliximab is effective in other organs such as the nervous system from this case report. At the time of seeing this patient, her neurological involvement was not active. There was no evidence of vasculitis or aneurysm in MRI of the brain, only old infarctions persisted. Therefore, her neurological signs and symptoms remained the same after infliximab treatment. Other supportive treatments are also important, particularly hypertensive control, because hypertension may increase the risk of aneurysm rupture6 as shown by the development of GI bleeding during uncontrolled hypertension. In patients with massive bleeding suspected to be caused by aneurysmal rupture, angiography is the best modality for both confirmations of diagnosis and therapeutic intervention. In the first episode of GI bleeding in our patient, angiography demonstrated the bleeding site and allowed for successful embolization. However, angiography could not demonstrate the bleeding site in the subsequent bleeding episodes. This might have been due to differences in the severity of bleeding in each episode. The patient had severe GI bleeding with shock in the first bleeding episode despite receiving a blood transfusion, whereas she had hemodynamically stable bleeding during the other episodes. Fortunately, after initiation of infliximab concomitant with other supportive treatments, the bleeding decreased and subsided. Therefore, early recognition and appropriate management of refractory disease are important to improve the outcome.

In conclusion, we have herein described a pediatric patient with PAN who presented with massive lower GI bleeding due to ruptured aneurysms, which is a rare but life-threatening presentation. Treatment with effective medications to control active disease in combination with radiological intervention for hemostasis is crucial. Infliximab should be considered to control refractory PAN with multiple aneurysms.

Acknowledgments

We thank our patient and her parents for allowing us to write this manuscript. We thank Angela Morben, DVM, ELS, from Edanz Group for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. The abstract of this paper was presented at the 13th Congress of Asian Society for Pediatric Research as a poster presentation with interim findings.

References

1. de Carpi JM, Castejón E, Masiques L, et al. Gastrointestinal involvement in pediatric polyarteritis nodosa. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44(2):274–278. doi:10.1097/01.mpg.0000235753.37358.72

2. Deguchi Y, Shibata N, Kishimoto S. Enhanced expression of the tumour necrosis factor/cachectin gene in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with systemic vasculitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;81(2):311–314. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb03336.x

3. Jarrot PA, Kaplanski G. Anti-TNF-alpha therapy and systemic vasculitis. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:1–9. doi:10.1155/2014/493593

4. Capuozzo M, Ottaiano A, Nava E, et al. Etanercept induces remission of polyarteritis nodosa: a case report. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:122. doi:10.3389/fphar.2014.00122

5. Stone JH. Polyarteritis nodosa. Jama. 2002;288(13):1632–1639.

6. Ebert EC, Hagspiel KD, Nagar M, et al. Gastrointestinal involvement in polyarteritis nodosa. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(9):960–966. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2008.04.004

7. Mocan H, Mocan M, Şen Y, et al. Fatal polyarteritis nodosa with massive mesenteric necrosis in a child. Clin Rheumatol. 1999;18(1):88–90.

8. Beckum KM, Kim DJ, Kelly DR, et al. Polyarteritis nodosa in childhood: recognition of early dermatologic signs may prevent morbidity. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31(1):e6–9. doi:10.1111/pde.12207

9. Pagnoux C, Mahr A, Cohen P, et al. Presentation and outcome of gastrointestinal involvement in systemic necrotizing vasculitides: analysis of 62 patients with polyarteritisnodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, Wegener granulomatosis, churg-strauss syndrome, or rheumatoid arthritis-associated vasculitis. Medicine. 2005;84(2):115–128.

10. Harada M, Yoshida H, Ikeda H, et al. Polyarteritisnodosa with mesenteric aneurysms demonstrated by angiography: report of a case and successful treatment of the patient with prednisolone and cyclophosphamide. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34(6):702–705.

11. Eleftheriou D, Dillon MJ, Tullus K, et al. Systemic polyarteritisnodosa in the young: a single‐center experience over thirty‐two years. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(9):2476–2485. doi:10.1002/art.38024

12. Eleftheriou D, Melo M, Marks SD, et al. Biologic therapy in primary systemic vasculitis of the young. Rheumatology. 2009;48(8):978–986. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kep148

13. de Kort SW, van Rossum MA, Ten Cate R. Infliximab in a child with therapy-resistant systemic vasculitis. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25(5):769–771. doi:10.1007/s10067-005-0071-7

14. Kendirli T, Yüksel S, Oral M, et al. Fatal polyarteritis nodosa with gastrointestinal involvement in a child. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22(12):810–812. doi:10.1097/01.pec.0000245172.38967.d0

15. Bas A, Samanci C, Numan F. Percutaneous transcatheter embolization of gastrointestinal bleeding in a child with polyarteritisnodosa. Pol J Radiol. 2014;79:465–466. doi:10.12659/PJR.892038

16. Yazici Z, Savci G, Parlak M, et al. Polyarteritisnodosa presenting with hemobilia and intestinal hemorrhage. Eur Radiol. 1997;7:1059–1061. doi:10.1007/s003300050252

17. Almgren B, Eriksson I, Foucard T, et al. Multiple aneurysms of visceral arteries in a child with polyarteritisnodosa. J Pediatr Surg. 1980;15(3):347–348.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.