Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 14

REAC neuromodulation treatments in subjects with severe socioeconomic and cultural hardship in the Brazilian state of Pará: a family observational pilot study

Authors Coelho Pereira JA , Rinaldi A , Fontani V , Rinaldi S

Received 5 January 2018

Accepted for publication 9 March 2018

Published 16 April 2018 Volume 2018:14 Pages 1047—1054

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S161646

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Video abstract presented by José Alfredo Coelho Pereira.

Views: 506

José Alfredo Coelho Pereira,1 Arianna Rinaldi,1,2 Vania Fontani,1,2 Salvatore Rinaldi1,2

1Research Department, Rinaldi Fontani Foundation, Florence, Italy; 2Department of Neuro Psycho Physio Pathology and Neuro Psycho Physical Optimization, Rinaldi Fontani Institute, Florence, Italy

Purpose: The purpose of this preliminary observational study was to evaluate the usefulness of a humanitarian initiative, aimed at improving the neuropsychological and behavioral attitude of children with severe socioeconomic and cultural hardship, in the Brazilian state of Pará. This humanitarian initiative was realized through the administration of two neuromodulation protocols, with radioelectric asymmetric conveyor (REAC) technology. During several years of clinical use, the REAC neuromodulation protocols have already proved to be effective in countering the effects of environmental stress on neuropsycho-physical functions.

Patients and methods: After the preliminary medical examination, all subjects were investigated with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), including the impact supplement with teacher’s report. After the SDQ, they received the neuromodulation treatment with REAC technology named neuro postural optimization (NPO), to evaluate their responsiveness. Subsequently, every 3 months all subjects underwent a treatment cycle of neuropsycho-physical optimization (NPPO) with REAC technology, for a total of three cycles. At the end of the last REAC-NPPO treatment cycle, all subjects were investigated once again with the SDQ. For the adequacy of the data, the Wilcoxon and the Signs tests were used. For the subdivision into clusters, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied for the adequacy of the procedure. For all the applied tests, a statistical significance of p<0.5 was found.

Results: The results showed that the REAC-NPO and REAC-NPPO neuromodulation protocols are able to improve the quality of life, the scholastic and socialization skills, and the overall state of physical and mental health in children of a family with severe socioeconomic and cultural hardship.

Conclusion: The REAC-NPO and REAC-NPPO neuromodulation protocols, due to their non-invasive characteristics, painlessness, and speed of administration, can be hypothesized as a treatment to improve the overall state of physical and mental health in a large number of people with socioeconomic and cultural discomfort.

Keywords: socioeconomic hardship, socioeconomic disparities, neuromodulation, radioelectric asymmetric conveyor, neuro postural optimization, neuropsycho-physical optimization

Introduction

Socioeconomic inequalities have strong influences on health,1–4 education, and school careers.5,6 As interventions to face this situation are often complex and expensive, socioeconomic and cultural disparities are becoming progressively larger, with serious repercussions affecting all aspects of social life.

This preliminary phase of investigation was carried out to evaluate the usefulness of a humanitarian initiative, aimed at improving the quality of life of families with severe socioeconomic and cultural distress, residing in the Brazilian state of Pará.

The aim of this study was to test if a sequence of two different neuromodulation protocols with radioelectric asymmetric conveyor (REAC) technology can improve the psychophysical state of subjects in severe socioeconomic and cultural hardship. In order to have a sample as homogeneous as possible, we chose to treat the members of a family group.

The two REAC neuromodulation protocols used were the neuro postural optimization (NPO) and the neuropsycho- physical optimization (NPPO). The REAC-NPO protocol has proved to be effective in optimizing encephalic electrometabolic functions, by inducing long-lasting changes in brain activation7–9 also in subjects with Alzheimer’s10,11 and other neurological diseases.12

The REAC-NPPO protocol has proven to be effective in treating stress-related symptoms,13–18 such as anxiety,19–21 pain,16 depression,19,20,22 and other psychiatric disorders23–25 also related to adaptation disorder.13,26–28 These two REAC neuromodulation protocols are absolutely non-invasive, painless and very fast and easy to be administered. Due to these characteristics, they could be ideal to treat a large number of subjects, in policies aimed to promote health and quality of life.

Patients and methods

Ethics

This observational study was conducted in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects and according to a study protocol approved by Comité de ética indipendente IRB – IEC, Governo do Estado do Pará, Secretaria de Estado de Edução, Escola Estadual de Ensino Fundamental e Médio “Rodrigues Pinagé,” with protocol number 0108/16 dated August 4, 2016. The father of the selected family provided written informed consent for the therapeutic treatment and for the case details to be published.

Aim, design, and setting of the study

This preliminary feasibility phase focused on one family group, in order to have a sample of subjects as homogeneous as possible and to minimize the influence of environmental variables.

The recruitment was done in a school attended by students with families in severe socioeconomic and cultural distress. The local school director invited students’ families to join the study on a voluntary basis and without any remuneration. Among the families that had joined, the school director selected a family consisting of the parents and five children, with particularly severe socioeconomic hardship.

Characteristics of participants

Upon initial medical examination, all the family members showed various types of wounds and injuries, edema, and bruises on the body.

Subject 1: male, 13 years old, during the first medical examination showed a general delayed physical and mental development, with short stature and cognitive impairment, difficulty in pronouncing intelligible words, aggressive attitudes and rapid behavioral changes, disobedience to rules or commands, difficulty in socialization with his classmates, poor school performance, and extreme difficulty in falling asleep. The boy also showed the triad: inattention, hyperactivity, impulsiveness, typical of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Subject 2: female, 11 years old, during the first medical examination showed difficulty in the organization of language, difficulty in pronouncing intelligible words, difficulty in socialization with her classmates, poor school performance, an extreme difficulty in falling asleep, and spending the night watching television.

Subject 3: female, 8 years old, during the first medical examination showed difficulty in verbal communication, with use of few words but in a clear and consistent way, difficulty in learning and in memory. She was not able to perform simple activities like associating numbers with colors and remembering the information provided by the evaluator. Moreover, she showed disobedience to rules or commands, poor school performance, and forefoot gait. She had easy crying crises during interpersonal interaction.

Subject 4: female, 6 years old, during the first medical examination showed a state of psychic agitation, aggressive attitude, crying crises, disobedience to rules or commands, difficulty in speaking and expressing sounds in an organized way, difficulty of fine motor control, and forefoot gait.

Subject 5: male, 5 years old, during the first medical examination showed cleft palate with previous surgical correction of cleft lip only. Moreover, he showed a state of psychic agitation, aggressive and jealous attitude, and difficulty in pronouncing intelligible words, difficulty in concentrating, memory problems and slow thinking, disobedience to rules or commands, and fear of sharp objects.

Interventions and comparisons

During the first medical examination, all subjects were investigated for the presence of fluctuating asymmetries (FAs). FA refers to small random deviations from perfect symmetry in bilaterally paired structures.29 FA reflects the organism’s ability to cope with genetic and environmental stress during development.29 FA can also indicate developmental stability and suggest the genetic fitness of an individual30 as an epigenetic measure of environmental stress31–33 and ADHD.34 The analysis of the FA can be performed by observing the morphological differences between the two hemisomes, in particular at face level.35,36 The analysis of FA can be performed also at functional level by observing the asymmetric activation of symmetrical muscle groups, such as the quadriceps femoris during the transition from the supine to the sitting position, during a motor task.8–11 The phenomenon thus observed takes the name of functional dysmetria.8,9 All subjects showed facial asymmetry and functional dysmetria.

After this first evaluation, all the subjects were investigated with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ).37–42 We have used the SDQ and Impact Supplement for the teachers specifically for 4–17 year olds. The SDQ Impact Supplement allows us to sum up the items on overall distress and impairment of the subject and generate an impact score. In fact, the teacher assesses whether the subject has difficulties in emotions, concentration, behavior, or being able to get on with other people and whether these difficulties upset or distress the subject and interfere with his or her everyday life. The teacher also assesses whether the difficulties of the subject constitute a burden for the teacher him- or herself or for the class as a whole.

A psychopedagogue assessed the subjects involved with the SDQ before the administration of the REAC-NPO protocol (T0) and immediately after the end of the third cycle of REAC-NPPO (T1).

Description of REAC technology

REAC for therapeutic use is a technology platform for biomodulation28,43–61 and neuromodulation,7,8,10,11,13–27,62 which has been shown to be effective even in neurodegenerative diseases.57,60 The scientific background of the REAC technology platform is based on a fundamental phenomenon for life: the cell polarity. Cell polarity is the asymmetric organization of several cellular components, including the plasma membrane, cytoskeleton, and organelles.63 This asymmetry can be used for specialized functions, such as maintaining a barrier within an epithelium or transmitting signals in neurons.64,65 The purpose of REAC technology is to recover and optimize the correct cell polarity.

The REAC-NPO neuromodulation protocol has been shown to be able to optimize neurotransmission in the whole encephalic mass, determining a more functional and economic response,7–9 also in neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.10–12 The REAC-NPO protocol consists of a single-administration treatment, which lasts for around 1 second. The REAC-NPPO neuromodulation protocol has been shown to optimize and improve the coping capacity toward environmental stressors13–19 and to be effective in various psychiatric disorders.20–26 The REAC-NPPO neuromodulation protocol consists of a treatment cycle of 18 sessions. Each session lasts for around 3 seconds. Every 3 months, the children underwent REAC-NPPO treatment cycles, for a total of three cycles. At the end of the last REAC- NPPO treatment cycle, they were investigated once again with the SDQ. None of the participants was subjected to any type of parallel treatment during the REAC-NPPO neuromodulation treatment cycles and the observation phase.

The REAC device used was a BENE model (ASMED, Florence, Italy).

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, we used IBM Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) 22.

The data collected with the SDQ have been analyzed with statistical tests and performed to check the adequacy of the data and procedure. For the adequacy of the data, Wilcoxon tests were used (Asymp, Sig two-tailed 0.013–0.196) and the Signs (Exact, Sig two-tailed 0.012–0.454). Regarding the subdivision into clusters (emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer problems, and prosocial), the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied for the adequacy of the procedure. For all the applied tests, a statistical significance of p<0.5 was found.

Results

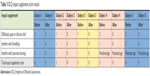

Subject 1: his Total Difficulties Score, generated by summing scores from all the scales except the prosocial scale, has improved from 32 at T0 (before REAC-NPPO), which corresponds to the Abnormal categorization, to 14 at T1 (after the end of the third REAC treatment cycle), which corresponds to the Borderline categorization. After the third REAC-NPPO neuromodulation treatment cycle, his score has moved to the threshold of Normality on all scales. In particular: emotional problems scale: total score from 5 = borderline to 3 = normal; conduct problems scale: total score from 9 = abnormal to 4 = normal; hyperactivity scale: total score from 9 = abnormal to 4 = normal; peer problems scale: total score from 9 = abnormal to 3 = normal (Tables 1 and 2). Moreover, during the REAC neuromodulation treatment cycles, he showed improvement in sleep quality and school performance.

| Table 1 SDQ teacher questionnaire results |

| Table 2 SDQ score table |

Subject 2: her Total Difficulties Score, generated by summing scores from all the scales except the prosocial scale, has improved from 24 at T0 (before REAC-NPPO), which corresponds to the abnormal categorization, to 10 at T1 (after the end of the third REAC-NPPO treatment cycle), which corresponds to the normal categorization. In particular: emotional problems scale: total score from 8 = abnormal to 3 = normal; conduct problems scale: total score from 4 = abnormal to 1 = normal; hyperactivity scale: total score from 4 = normal to 2 = normal; peer problems scale: total score from 8 = abnormal to 4 = borderline (Tables 1 and 2). Moreover, during the REAC neuromodulation treatment cycles, she showed improvement in sleep quality and school performance.

Subject 3: her Total Difficulties Score, generated by summing scores from all the scales except the prosocial scale, has improved from 17 at T0 (before REAC-NPPO), which corresponds to the abnormal categorization, to 7 at T1 (after the end of the third REAC-NPPO treatment cycle), which corresponds to the normal categorization. In particular: emotional problems scale: total score from 4 = normal to 2 = normal; conduct problems scale: total score from 2 = normal to 0 = normal; hyperactivity scale: total score from 6 = borderline to 2 = normal; peer problems scale: total score from 5 = abnormal to 3 = normal (Tables 1 and 2). Moreover, during the REAC neuromodulation treatment cycles, she started to walk correctly and improved her school performance.

Subject 4: her Total Difficulties Score, generated by summing scores from all the scales except the prosocial scale, has improved from 26 at T0 (before REAC-NPPO), which corresponds to the abnormal categorization, to 14 at T1 (after the end of the third REAC-NPPO treatment cycle), which corresponds to the borderline categorization. In particular: emotional problems scale: total score from 3 = normal to 2 = normal; conduct problems scale: total score from 7 = abnormal to 3 = borderline; hyperactivity scale: total score from 9 = abnormal to 5 = normal; peer problems scale: total score from 7 = abnormal to 4 = borderline (Tables 1 and 2). Moreover, she improved her ability to pronounce intelligible words.

Subject 5: his Total Difficulties Score, generated by summing scores from all the scales except the prosocial scale, has improved from 23 at T0 (before REAC-NPPO), which corresponds to the abnormal categorization, to 15 at T1 (after the end of the third REAC-NPPO treatment cycle), which corresponds to the borderline categorization. In particular: emotional problems scale: total score from 4 = normal to 3 = normal; conduct problems scale: total score from 4 = abnormal to 3 = borderline; hyperactivity scale: total score from 8 = abnormal to 7 = abnormal; peer problems scale: total score from 7 = abnormal to 2 = normal (Tables 1 and 2). Moreover, he improved his motor control and gait and his communication ability, starting to pronounce short words.

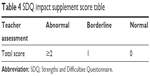

All the subjects involved showed a marked improvement compared to their initial state, as shown by the passage of category of their scores, according to the SDQ Impact Supplement score table for 4–17 year olds (Tables 3 and 4).

| Table 3 SDQ impact supplement score results |

| Table 4 SDQ impact supplement score table |

Discussion

The growing socioeconomic and cultural disparities represent a serious social problem,66 which has been exacerbating in recent years. An attempt to reduce this social gap is the activation of sustainable initiatives to improve the mental and physical health of the disadvantaged population,67–69 in order to allow a positive socioeconomic and cultural evolution of this population. For this purpose, it may be useful to choose approaches that do not require understanding and social interaction, since subjects belonging to disadvantaged populations often have severe limitations in these abilities.70 Furthermore, the natural distrust of these populations71,72 requires simple approaches, easy to be administered, and non-invasive both at the physical and mental level. The REAC-NPO and REAC-NPPO neuromodulation protocols have been specifically designed to be administered to large numbers of people, in a simple and effective way, avoiding interpersonal conditioning.

The experience carried out in this preliminary phase of this humanitarian initiative confirms that the REAC-NPO and REAC-NPPO neuromodulation protocols are effective in improving the neuropsycho-physical pictures,10–27,62 even in subjects who do not have clear cultural skills to understand the usefulness of the treatment they receive.

Although the efficacy of REAC neuromodulation protocols in improving the neuropsycho-physical response to environmental interaction has already been demonstrated,13–17,19 it is the first time that these treatments have been used for the same intended use, but in a population defined with severe socioeconomic and cultural hardship. For this reason, it will be appropriate to proceed with a larger sample, to better understand the impact of these REAC neuromodulation protocols in improving neuropsychological and behavioral attitude of these populations.

Conclusion

The experience and results achieved in the preliminary phase of this humanitarian initiative seem to prove that REAC-NPO and REAC-NPPO neuromodulation protocols, due to their non-invasive characteristics, painlessness, and speed of administration, can be hypothesized as a treatment to improve the overall state of physical and mental health in a large number of people with socioeconomic and cultural hardship.73

Acknowledgment

We thank Professor Maria das Graças de Souza Lima, Universidade Estadual do Pará, Dr Alessandra Cappelli, and Dr Matteo Lotti Margotti, Rinaldi Fontani Institute, for their precious cooperation.

Author contributions

JACP conceived and designed the experimental plan, wrote the manuscript, and performed the experiments. AR conceived and designed the experimental plan, performed the statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript. SR and VF invented REAC technology, collaborated in conceiving the experimental design, wrote the manuscript, and supervised the project. All authors contributed towards data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

There is a potential competing interest as SR and VF are the inventors of the REAC technology. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Schrecker T, Milne E. Looking upstream for influences on socioeconomic inequalities in health. J Public Health. 2014;36(3):353–354. | ||

van Lenthe FJ, Kamphuis CB, Beenackers MA, et al. Cohort profile: understanding socioeconomic inequalities in health and health behaviours: the GLOBE study. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(3):721–730. | ||

Ortiz-Hernández L, Pérez-Salgado D, Tamez-González S. Desigualdad socioeconómica y salud en México. [Socioeconomic inequality and health in Mexico]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2015;53(3):336–347. Spanish. | ||

Mújica OJ, Vázquez E, Duarte EC, Cortez-Escalante JJ, Molina J, Barbosa da Silva Junior J. Socioeconomic inequalities and mortality trends in BRICS, 1990–2010. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(6):405–412. | ||

Marks GN, Cresswell J, Ainley J. Explaining socioeconomic inequalities in student achievement: the role of home and school factors. Educat Res Eval. 2006;12(2):105–128. | ||

Monteiro CA, Benicio MH, Conde WL, et al. Narrowing socioeconomic inequality in child stunting: the Brazilian experience, 1974–2007. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(4):305–311. | ||

Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Castagna A. Brain activity modification produced by a single radioelectric asymmetric brain stimulation pulse: a new tool for neuropsychiatric treatments. Preliminary fMRI study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:649–654. | ||

Mura M, Castagna A, Fontani V, Rinaldi S. Preliminary pilot fMRI study of neuropostural optimization with a noninvasive asymmetric radioelectric brain stimulation protocol in functional dysmetria. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2012;8:149–154. | ||

Rinaldi S, Mura M, Castagna A, Fontani V. Long-lasting changes in brain activation induced by a single REAC technology pulse in Wi-Fi bands. Randomized double-blind fMRI qualitative study. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5668. | ||

Olazarán J, González B, López-Álvarez J, et al. Motor effects of REAC in advanced Alzheimer’s disease: results from a pilot trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;36(2):297–302. | ||

Olazarán J, González B, Osa-Ruiz E, et al. Motor effects of radio electric asymmetric conveyer in Alzheimer’s disease: results from a cross-over trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(1):325–332. | ||

Fontani V, Rinaldi S, Castagna A, Margotti ML. Noninvasive radioelectric asymmetric conveyor brain stimulation treatment improves balance in individuals over 65 suffering from neurological diseases: pilot study. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2012;8:73–78. | ||

Collodel G, Moretti E, Fontani V, et al. Effect of emotional stress on sperm quality. Indian J Med Res. 2008;128(3):254–261. | ||

Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Aravagli L, Lotti Margotti M. Psychological and symptomatic stress-related disorders with radio-electric treatment: psychometric evaluation. Stress Health. 2010;26(5):350–358. | ||

Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Aravagli L, Mannu P. Psychometric evaluation of a radio electric auricular treatment for stress related disorders: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled controlled pilot study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:31. | ||

Fontani V, Rinaldi S, Aravagli L, Mannu P, Castagna A, Margotti ML. Noninvasive radioelectric asymmetric brain stimulation in the treatment of stress-related pain and physical problems: psychometric evaluation in a randomized, single-blind placebo-controlled, naturalistic study. Int J Gen Med. 2011;4:681–686. | ||

Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Aravagli L, et al. Stress-related psycho-physiological disorders: randomized single blind placebo controlled naturalistic study of psychometric evaluation using a radio electric asymmetric treatment. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:54. | ||

Fontani V, Aravagli L, Margotti ML, Castagna A, Mannu P, Rinaldi S. Neuropsychophysical optimization by REAC technology in the treatment of: sense of stress and confusion. Psychometric evaluation in a randomized, single blind, sham-controlled naturalistic study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:195–199. | ||

Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Moretti E, et al. A new approach on stress-related depression & anxiety: neuro-psycho- physical-optimization with radio electric asymmetric-conveyer. Indian J Med Res. 2010;132:189–194. | ||

Olivieri EB, Vecchiato C, Ignaccolo N, et al. Radioelectric brain stimulation in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder with comorbid major depression in a psychiatric hospital: a pilot study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:449–455. | ||

Fontani V, Mannu P, Castagna A, Rinaldi S. Social anxiety disorder: radio electric asymmetric conveyor brain stimulation versus sertraline. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:581–586. | ||

Mannu P, Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Castagna A, Margotti ML. Radio electric treatment vs. Es-Citalopram in the treatment of panic disorders associated with major depression: an open-label, naturalistic study. Acupunct Electrother Res. 2009;34(3–4):135–149. | ||

Mannu P, Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Castagna A. Long-term treatment of bipolar disorder with a radioelectric asymmetric conveyor. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:373–379. | ||

Mannu P, Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Castagna A. Radio electric asymmetric brain stimulation in the treatment of behavioral and psychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer disease. Clin Interv Aging. 2011;6:207–211. | ||

Mannu P, Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Castagna A, Margotti ML. Noninvasive brain stimulation by radioelectric asymmetric conveyor in the treatment of agoraphobia: open-label, naturalistic study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:575–580. | ||

Castagna A, Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Aravagli L, Mannu P, Margotti ML. Does osteoarthritis of the knee also have a psychogenic component? Psycho-emotional treatment with a radio-electric device vs. intra-articular injection of sodium hyaluronate: an open-label, naturalistic study. Acupuncture Electro-Ther Res. 2010;35(1–2):1–16. | ||

Castagna A, Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Mannu P. Radioelectric asymmetric brain stimulation and lingual apex repositioning in patients with atypical deglutition. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2011;4:209–213. | ||

Castagna A, Fontani V, Rinaldi S, Mannu P. Radio electric tissue optimization in the treatment of surgical wounds. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2011;4:133–137. | ||

Tomkins JL, Kotiaho JS. Fluctuating asymmetry. In: Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2001. | ||

Dongen SV. Fluctuating asymmetry and developmental instability in evolutionary biology: past, present and future. J Evol Biol. 2006;19(6):1727–1743. | ||

Parsons PA. Fluctuating asymmetry: an epigenetic measure of stress. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 1990;65(2):131–145. | ||

Fink B, Weege B, Manning JT, Trivers R. Body symmetry and physical strength in human males. Am J Hum Biol. 2014;26(5):697–700. | ||

Lalumiere ML, Harris GT, Rice ME. Psychopathy and developmental instability. Evol Hum Behav. 2001;22(2):75–92. | ||

Burton C, Stevenson JC, Williams DC, Everson PM, Mahoney ER, Trimble JE. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (AD/HD) and fluctuating asymmetry (FA) in a college sample: an exploratory study. Am J Hum Biol. 2003;15(5):601–619. | ||

Zadzińska E, Kozieł S, Kurek M, Spinek A. Mother’s trauma during pregnancy affects fluctuating asymmetry in offspring’s face. Anthropol Anz. 2013;70(4):427–437. | ||

Quinto-Sánchez M, Adhikari K, Acuña-Alonzo V, et al. Facial asymmetry and genetic ancestry in Latin American admixed populations. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2015;157(1):58–70. | ||

Rothenberger A, Woerner W. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) – evaluations and applications. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;13 Suppl 2:II1–2. | ||

Hoofs H, Jansen NW, Mohren DC, Jansen MW, Kant IJ. The context dependency of the self-report version of the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): a cross-sectional study between two administration settings. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0120930. | ||

Caro-Cañizares I, Serrano-Drozdowskyj E, Pfang B, Baca-Garcia E, Carballo JJ. SDQ dysregulation profile and its relation to the severity of psychopathology and psychosocial functioning in a sample of children and adolescents with ADHD. J Atten Disord. Epub 2017, Feb 1. | ||

Cheng S, Keyes KM, Bitfoi A, et al. Understanding parent-teacher agreement of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): comparison across seven European countries. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. Epub 2017, Oct 12. | ||

Kunze B, Wang B, Isensee C, et al. Gender associated developmental trajectories of SDQ-dysregulation profile and its predictors in children. Psychol Med. 2018;48(3):404–415. | ||

Ortuño-Sierra J, Aritio-Solana R, Fonseca-Pedrero E. Mental health difficulties in children and adolescents: the study of the SDQ in the Spanish National Health Survey 2011–2012. Psychiatry Res. 2018;259:236–242. | ||

Fontani V, Castagna A, Mannu P, Rinaldi S. Radioelectric asymmetric stimulation of tissues as treatment for post-traumatic injury symptoms. Int J Gen Med. 2011;4:627–634. | ||

Collodel G, Rinaldi S, Moretti E, et al. The effect of radio electric asymmetric conveyer treatment on sperm parameters of subfertile stallions: a pilot study. Reprod Biol. 2012;12(3):277–284. | ||

Maioli M, Rinaldi S, Santaniello S, et al. Radiofrequency energy loop primes cardiac, neuronal, and skeletal muscle differentiation in mouse embryonic stem cells: a new tool for improving tissue regeneration. Cell Transplant. 2012;21(6):1225–1233. | ||

Rinaldi S, Maioli M, Santaniello S, et al. Regenerative treatment using a radioelectric asymmetric conveyor as a novel tool in antiaging medicine: an in vitro beta-galactosidase study. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:191–194. | ||

Collodel G, Fioravanti A, Pascarelli NA, et al. Effects of regenerative radioelectric asymmetric conveyer treatment on human normal and osteoarthritic chondrocytes exposed to IL-1beta. A biochemical and morphological study. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:309–316. | ||

Maioli M, Rinaldi S, Santaniello S, et al. Anti-senescence efficacy of radio-electric asymmetric conveyer technology. Age (Dordr). 2014;36(1):9–20. | ||

Maioli M, Rinaldi S, Santaniello S, et al. Radio electric conveyed fields directly reprogram human dermal skin fibroblasts toward cardiac, neuronal, and skeletal muscle-like lineages. Cell Transplant. 2013;22(7):1227–1235. | ||

Rinaldi S, Iannaccone M, Magi GE, et al. Physical reparative treatment in reptiles. BMC Vet Res. 2013;9(1):39. | ||

Maioli M, Rinaldi S, Santaniello S, et al. Radioelectric asymmetric conveyed fields and human adipose-derived stem cells obtained with a nonenzymatic method and device: a novel approach to multipotency. Cell Transplant. 2014;23(12):1489–1500. | ||

Rinaldi S, Maioli M, Pigliaru G, et al. Stem cell senescence. Effects of REAC technology on telomerase-independent and telomerase-dependent pathways. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6373. | ||

Maioli M, Rinaldi S, Migheli R, et al. Neurological morphofunctional differentiation induced by REAC technology in PC12. A neuro protective model for Parkinson’s disease. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10439. | ||

Panaro MA, Carofiglio V, Calvello R, et al. Modulation of pro-inflammatory response in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease by non-invasive physical approach. Paper presented at: Microwave Symposium (MMS), 2015 IEEE 15th Mediterranean; November 30, 2015–December 2, 2015. | ||

Rinaldi S, Calzá L, Giardino L, Biella GE, Zippo AG, Fontani V. Radio electric asymmetric conveyer: a novel neuromodulation technology in Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:22. | ||

Zippo AG, Rinaldi S, Pellegata G, et al. Electrophysiological effects of non-invasive radio electric asymmetric conveyor (REAC) on thalamocortical neural activities and perturbed experimental conditions. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18200. | ||

Lorenzini L, Giuliani A, Sivilia S, et al. REAC technology modifies pathological neuroinflammation and motor behaviour in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35719. | ||

Maioli M, Rinaldi S, Pigliaru G, et al. REAC technology and hyaluron synthase 2, an interesting network to slow down stem cell senescence. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28682. | ||

Berlinguer F, Pasciu V, Succu S, et al. REAC technology as optimizer of stallion spermatozoa liquid storage. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2017;15(1):11. | ||

Panaro MA, Aloisi A, Nicolardi G, et al. Radio electric asymmetric conveyer technology modulates neuroinflammation in a mouse model of neurodegeneration. Neurosci Bull. 2018;34(2):270–282. | ||

Sanna Passino E, Rocca S, Caggiu S, et al. REAC regenerative treatment efficacy in experimental chondral lesions: a pilot study on ovine animal model. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:1471–1479. | ||

Castagna A, Rinaldi S, Fontani V, Mannu P, Margotti ML. Comparison of two treatments for coxarthrosis: local hyperthermia versus radio electric asymmetrical brain stimulation. Clin Interv Aging. 2011;6:201–206. | ||

Orlando K, Guo W. Membrane organization and dynamics in cell polarity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1(5):a001321. | ||

Urban NN, Castro JB. Functional polarity in neurons: what can we learn from studying an exception? Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20(5):538–542. | ||

Horton AC, Ehlers MD. Neuronal polarity and trafficking. Neuron. 2003;40(2):277–295. | ||

Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186:69–101. | ||

Andrade LH, Benseñor IM, Viana MC, Andreoni S, Wang YP. Clustering of psychiatric and somatic illnesses in the general population: multimorbidity and socioeconomic correlates. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2010;43(5):483–491. | ||

Carvalho PD, Barros MV, Lima RA, Santos CM, Mélo EN. Comportamentos de risco à saúde e indicadores de sofrimento psicossocial em estudantes do ensino médio. [Health risk behaviors and psychosocial distress indicators in high school students]. Cad Saude Publica. 2011;27(11):2095–2105. Portuguese. | ||

Coelho CLS, Laranjeira RR, Santos JLF, et al. Depressive symptoms and alcohol correlates among Brazilians aged 14 years and older: a cross-sectional study. Subst Abuse Treat Prevent Policy. 2014;9(1):29. | ||

Waisel DB. Vulnerable populations in healthcare. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2013;26(2):186–192. | ||

Yang TC, Chen IC, Noah AJ. Examining the complexity and variation of health care system distrust across neighborhoods: implications for preventive health care. Res Sociol Health Care. 2015;33:43–66. | ||

Armstrong K, Ravenell KL, McMurphy S, Putt M. Racial/ethnic differences in physician distrust in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1283–1289. | ||

Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson N. Understanding associations between race, socioeconomic status and health: patterns and prospects. Health Psychol. 2016;35(4):407–411. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.