Back to Journals » HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care » Volume 13

Rate of Viral Re-Suppression and Retention to Care Among PLHIV on Second-Line Antiretroviral Therapy at Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northeast Ethiopia: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Authors Wedajo S , Degu G, Deribew A , Ambaw F

Received 4 June 2021

Accepted for publication 21 August 2021

Published 7 September 2021 Volume 2021:13 Pages 877—887

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S323445

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Bassel Sawaya

Shambel Wedajo,1 Getu Degu,2 Amare Deribew,3 Fentie Ambaw2

1School of Public Health, CMHS, Wollo University, Dessie, Ethiopia; 2School of Public Health, CMHS, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia; 3Nutrition International (NI) in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Shambel Wedajo Tel +251 913893606

Email [email protected]

Background: In Ethiopia, first-line antiretroviral therapy failure is growing rapidly. However, unlike first-line therapy, to date, very little is known about the outcomes of second-line therapy. Thus, this study assessed the rate of viral re-suppression and attrition to care and their predictors among people living with HIV on second-line therapy.

Methods: A retrospective cohort study was conducted on 642 people living with HIV at Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital from October 2016 to November 2019. A proportional Cox regression model was computed to explore predictors of viral re-suppression (viral load less than 1000 copies/mL) and attrition to care.

Results: Out of 642 subjects, 19 (3%), 44 (6.9%), 70 (10.9%), and 509 (79.3%) patients were lost to follow up, died, transferred out, and alive on care, respectively. Similarly, 82.39% (95% CI: 79.24– 85.16%) of patients had achieved viral re-suppression, with 96 per 100 person-year rate of re-suppression. Patients who switched timely to second-line therapy were at a higher rate of viral re-suppression than delayed patients [adjusted hazard rate, AHR = 1.43 (95% CI: 1.17– 1.74)]. Not having drug substitution history [AHR = 1.25 (95% CI: 1.02– 1.52)] was positively associated with viral re-suppression. In contrast, being on anti-TB treatment [AHR = 0.67 (95% CI: 0.49– 0.91)] had lower likelihood with viral re-suppression. In the current study, attrition to care was 11% (95% CI: 8.7– 13.9%). Ambulatory or bedridden patients were more at risk of attrition to care as compared with workable patients [AHR = 2.61 (95% CI: 1.40– 4.87)]. Similarly, being not virally re-suppressed [AHR = 6.87 (95% CI: 3.86– 12.23)] and CD4 count ≤ 450 cells/mm3 [AHR = 2.61 (95% CI: 1.40– 4.87)] were also positively associated with attrition to care.

Conclusion: A significant number of patients failed to achieve viral re-suppression and attrition from care. Most identified factors related to patient monitoring. Hence, patient-centered intervention should be strengthened, besides treatment switch.

Keywords: second-line therapy, re-suppression, retention to care, attrition

Introduction

Globally, more than 26 million people living with HIV (PLHIV) have accessed antiretroviral therapy (ART) by the end of 2020,1 which has resulted in significant reduction in HIV-related morbidity and mortality. However, the proportion of first-line regimen failure and the demand for second-line antiretroviral therapy is growing rapidly. A mathematical model done in sub-Saharan Africa to estimate the need of second-line antiretroviral therapy showed that in 2020 and 2030, 2.9–15.6% and 6.6–19.6% PLHIV will receive second-line ART, respectively.2 A systematic review done in Ethiopia also showed that 15.9% (11.6–20.1%) of PLHIV had experienced first-line regimen failure and required to switch to second-line therapy.3

After exposure of second-line antiretroviral therapy, patients are expected to achieve viral re-suppression (ie, viral load measurement below 1000 copies/mL), improve clinical condition, and retention to care (ie, not lost to follow up or died).4 However, this is may not be true for all patients. Failure to achieve viral re-suppression and attrition from care have multi-dimension clinical and public health consequences. It has also an implication on implementation of current strategies and policies in local context.

Currently, a significant number of PLHIV had started second-line antiretroviral therapy. This therapy requires more than double the cost of the first-line therapy.5,6 Nevertheless, unlike first-line therapy, to date, very little is known locally about the outcomes of patients on second-line antiretroviral therapy.

Previous studies revealed that viral re-suppression and retention to care among patients on second-line therapy was heterogeneous, which range from 41%7 to 83.1%8 and 64.7%9 to 92.5%,10 respectively. Further, even if a few studies were done previously, the viral cutoff point (40011–15 or 5007,8 copies/mL) to define viral re-suppression was not in agreement with WHO-2016 consolidated guidelines (<1000 copies/mL)4,16 or patient treatment outcomes evaluated using immunological and clinical failure criteria.17 Both methods did not show the amount of virus in the blood directly and low sensitive and positive predictive value.4,16 These inconsistencies limit the application of those evidences in low income countries. Hence, local evidence is needed for context based decision making. Besides, factors which lead to poor treatment outcomes may relate to clinical and non-clinical determinants as well as vary from place to place and failed to consider in previous studies.18

A better understanding of the outcomes of second-line therapy and its determinants in local context allows policy makers and implementers to craft more appropriate interventions, prevent drug resistance, and reduce the risk of further treatment failure that limit the switch to more expensive third-line regimen. Therefore, this study was conducted to determine the rate of viral re-suppression and attrition to care and their predictors among PLHIV on second-line antiretroviral therapy.

Materials and Methods

Setting

This study was conducted at Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (DCSH) from October 2016 to November 2019. Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital is located in the Amhara region, northeast Ethiopia, which serves the top HIV burden area in the nation.19 Currently, 5557 and 1076 PLHIV are taking first-line antiretroviral therapy and ever enrolled to second-line therapy, respectively.

In Ethiopia, current standard second-line antiretroviral therapy consists of a combination of a combination of three ARV drugs (at least two of which are new to the patient); two Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs) as a backbone; Lamivudine (3TC) and Abacavir (ABC), or Zidovudine (ZDV) or Tenofovir (TDF) and one Protease Inhibitor (PI); Lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) or Atazanavir/ritonavir (ATV/r).4,16

Similarly, in Ethiopia, PLHIV data are handled by SMART care, ART registration/log book, and chronic ART follow up form/patient chart. Patient chart is the main source of data which is filled with a trained health professional, and includes detail data elements. The SMART care electronic database is another source of data for patients on ART. It is filled by trained non-health professional/data clerks by reviewing patient charts. SMART care has only few key data elements like CD4, TB screen, and viral load. ART registration/log book is similar to SMART care, except it is filled manually.

Antiretroviral treatment success is monitored using viral load (VL) measurement in which viral load measurement is done after initiation of ART at six months, 12 months, and every 12 months. If two consecutive VL results more than 1000 copies/mL with enhanced adherence support confirm failure of the current treatment regimen, patients will switch to second-line regimen. In Ethiopia, viral load measurement was started in 2016 on top 20 burden areas including Dessie Comprehensive Specialized hospital.20,21

Study Design

A retrospective cohort study was conducted among PLHIV who started second-line antiretroviral therapy from October 2016 to November 2019.

Study Population

Adult PLHIV who have received second-line antiretroviral therapy at Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital were considered as the target population. Patients who were not taken second-line antiretroviral therapy for at least six months or had no viral load measurement after the commencement of second-line therapy were excluded.

Sample Size

The minimum representative sample size was calculated using EPI-Info statCalk by taking AHR: 1.83 for switched to second-line for reasons not related to noncompliance with first-line, 11.33% of outcome in the unexposed group from a study done in South Africa.12 As well as by considering 95% confidence level, 80% power, and one to one unexposed to exposed ratio, which gave 522 samples.

Dependent Variables

The primary outcome variable in this study was viral re-suppression (event) which is defined as having viral load measurement below 1000 copies/mL after at least six-month exposure of second antiretroviral therapy.4,16 In contrast, patients who were lost to follow up, withdrew, or failed to viral suppression during the study period were considered as censored.

The secondary outcome variable of this study was attrition to care, which is defined as patients who died or were lost to care (missed contact with the health facility for three consecutive months) considered as event after initiation of second-line therapy. In contrast, patients who are alive and in care on a second-line regimen at the time of data collection were considered as censored (retained on care) and coded as zero. Transferred out patients were excluded from the analysis of attrition. After transferred out, the status of those patients was unknown. If we considered transferred out cases as alive in care, it will undermine the attrition, and the reverse is also true. Hence, in this study transferred out cases were not considered in determining attrition to care.

Independent Variables

Socio-demographic profiles: age, sex, marital status, educational status, and disclosure status.

Clinical profile at therapy switch includes: year on ART, body mass index, functional status, WHO clinical stage, TB treatment status, TB preventive therapy (INH), CD4 cell/mm3, viral load, first-line ART regimen before switch, drug substitution history during first-line therapy, second-line ARV regimen, medication adherence, and time between first virological failure and initiation of second-line therapy. Timely switch was defined based on first virological failure (VL≥1000 copies/mL) in which high viral load patients enrolled to three-month enhanced adherence support (EAS). After completing the EAS session, the second viral load will be done and patients having viral load measurement ≥1000 copies/mL considered as treatment failure, and switched to next level therapy. Patients who switch based on the above standard were considered as timely switch, and if not considered as delayed to switch.4,16 Medication adherence was assessed by reviewing the patient follow up form, which was collected via self-report and filled by health professional. Patients who take ≥95% of the prescribed medication were considered as good adherence. Similarly, patients who take 85–94% and less than 85% of the prescribed medication were considered as fair and poor respectively. This cutoff point was according to national and WHO consolidated antiretroviral guidelines.16,22

Data Collection

The data were collected by trained health professional using a structured data extraction checklist for one month duration. The extraction was made by reviewing chronic HIV follow up form (patient chart or card), ART registration book, and SMART care electronic database for patients who started second-line antiretroviral therapy from October 2016 to November 2019. The extraction sheet was prepared in accordance with the national consolidated antiretroviral guideline.16 Patient chart or card was retrieved using patient Medical Record Number (MRN) and unique ART registration number. The qualities of data were secured by triangulation of the above data sources; minimize data incompleteness and inconsistency, using a pre-tested extraction checklist, employing trained data collectors, and conducting on-site supervision.

Data Analysis

Data were entered into EpiData Version 3.1 software, and then, exported to Stata version 14 for further analysis. Proportion for categorical variables and median with interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables were computed after considering distributional assumption tests. Incidence rate of viral re-suppression and attrition to care was calculated using person time of observations. Person-time is the sum of the number of years contributed by study participants in the follow-up period. A proportional Cox regression model was computed to identify significant predictor variables after proportional hazard ratio assumption checked using a global goodness of fit test (Schoenfeld residuals). First bi-variable Cox regression was done, and variables having P-value less than 0.25 imported to a multivariable model. In the multivariable proportional Cox model, variables having P-value less than 0.05 was decided statistically significant.

Results

Study Participants

During the three-year follow-up period, 686 adult PLHIV started second-line antiretroviral therapy, of which, 642 patients had taken second-line antiretroviral therapy for more than six months and had viral load measurement, and were included in the study. Out of 642 study participants, 19 (3%), 44 (6.9%), 70 (10.9%), and 509 (79.30%) patients were lost to follow up, died, transferred out, and alive on care, respectively. Regarding treatment success, 529 (82.39%) of 642 patients had achieved viral re-suppression (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Viral re-suppression and attrition to care among PLHIV on second-line therapy at Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (DCSH), northeast Ethiopia, from October 2016 to November 2019. |

Characteristic of Study Participants

Concerning sociodemographic profiles, 359 (55.9%) were female and nearly fifty percent were married out of 642 study participants. One third of participants had not attended formal education, and 181 (28.2%) were unemployed. Concerning disclosure of HIV status, 538 (83.8%) patients disclosed their status for at least one of the family members (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Profile of PLHIV on Second-Line Antiretroviral Therapy at Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northeast Ethiopia, October 2016–November 2019 (n=642) |

Clinical Characteristics of PLHIV at Therapy Switch

Out of 642 subjects, 466 (72.8%) and 140 (21.8%) participants had BMI ≥18.5 kg/m2 and CD4 count greater than 450 cells/mm3 at the start of second-line therapy. Similarly, 85 (13.2%) and 19 (3%) participants had advanced clinical stage and bedridden at therapy switch. Fifteen percent of participants were on anti-TB treatment during the first six months of second-line therapy and 350 (54.51%) had not taken TB preventive therapy (INH). TDF-3TC-EFV (219 (34.1%)) and TDF-3TC-ATV/r (283 (44.1%)) were the most prescribed first and second-line antiretroviral regimens.

Regarding medication adherence and drug substitution, 574 (89.4%) patients had good adherence while on second-line antiretroviral therapy and 448 (69.8%) patients had no drug substitution history while on first-line therapy. The median (IQR) time between the first virological failure and the start of second-line therapy was 5 (3–8) months and 431 (67.13%) participants delayed to switch timely after first virological failure (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Clinical Profiles of PLHIV at the Start of Second-Line Therapy, Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northeast Ethiopia, October 2016–November 2019 (n=642) |

Rate of Viral Re-Suppression and Predictors

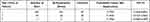

In general, 82.39% (95% CI: 79.24–85.16%) of 642 PLHIV on second-line therapy had achieved viral re-suppression, with 96 per 100 person-year rate of re-suppression in 550.16 year follow up. Out of 642 study participants, 77.03% (95% CI: 73.58–80.31%) patients had achieved viral re-suppression during the first year following exposure of second-line therapy (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Life Table on Viral Re-Suppression Among PLHIV on Second-Line Therapy, Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, October 2016–November 2019 (n=642) |

After at least six month exposure of second-line therapy, 209 patients showed high viral load measurement (≥1000 copies/mL), and enrolled to enhanced adherence support (EAS). After EAS intervention, 96 (46%) patients had achieved viral re-suppression, and 39 (18.66%) patients not achieved viral re-suppression. The remaining 74 (35.4%) were still on EAS and second viral load not yet done.

Patients who switched timely to second-line antiretroviral therapy were 1.43 times more likely to have viral re-suppression at any time as compared to delayed patients, while holding all other variables in the model constant [AHR=1.43 (95% CI: 1.17–1.74)]. Similarly, patients who had not drug substitution history were 1.25 times more likely to have viral re-suppression at any time as compared with drug substituted patients [AHR=1.25 (95% CI: 1.02–1.52)].

Patients who had viral load measurement 1000–4140 copies/mL and 4141–13,195 copies/mL at therapy switch were 1.60 and 1.38 times more likely to have viral re-suppression at any time as compared with the reference category (VL ≥52,753 copies/mL), respectively. Patients who were on anti-TB treatment during the first six months of second-line therapy were on average 33% decrease on the likely of viral re-suppression as compared with the counterparts [AHR =0.67 (95% CI: 0.49–0.91)], while holding all other variables in the model constant (Table 4).

Attrition to Care and Predictors

By excluding seventy transferred out cases, 63 (11%, 95% CI: 8.7–13.9%) out of 572 patients were failed to retain on care with 7.1 per 100 person-year rate of attrition in 887.25 year observation. From attrition patients, 19 (3.3%) and 44 (7.7%) were lost to follow up and died, respectively. The cumulative proportions of attrition to care at year 1, 2, 3 were 7.16% (95% CI: 5.2–9.8%), 13.36% (95% CI: 10.31–17.23%), 21.62% (95% CI: 16.30–28.35%), respectively.

Patients who were ambulatory or bedridden at the time of therapy switch were 2.61 times more at risk of attrition to care at any time due to death or loss to follow up as compared with workable patients [AHR=2.61 (95% CI: 1.40–4.87)]. Similarly, patients whose CD4 cell count less than 450 copies/mm3 were 3.81 times more at risk of attrition to care at any time as compared with the counterparts [AHR=3.81 (95% CI: 1.17–12.39)]. Patients who failed to achieve viral re-suppression were 6.87 times more at risk of attrition to care as compared with viral re-suppressed patients [AHR= 6.87 (95% CI: 3.86–12.23)] (Table 5).

Discussion

The present study shows that nearly one in five PLHIV on second-line therapy failed to achieve viral re-suppression. This finding was in agreement with studies conducted in resource limited settings8–10,23–25 and higher than a study conducted in South Africa.12 This variation is due to a difference in viral load measurement classification. Viral load measurement below 400 copies/mL and 1000 copies/mL was taken as cutoff point to define viral re-suppression in the study conducted in South Africa and current study, respectively. In general, viral re-suppression in this study is still not in agreement with national and WHO/UNAIDS settled targets on viral suppression in 2030, which says 95% of people on treatment will have suppressed viral load in 2030.26 Not achieving viral re-suppression has both clinical and public health implications. Clinically, it increases the risk of drug resistance, second-line treatment failure, and demand of high cost third-line antiretroviral therapy. Besides, at the public level, it also increases the chance of HIV transmission, even resistant strain.

Eleven percent of patients on second-line therapy had experienced attrition to care. This finding was in line with a study done in Rwanda10 and higher than the result of other studies.8,9,12,27,28 This variation is due to a difference in computing attrition, that is transferred out cases were included in previous studies as denominator but not in this study. Nonretained patients have a greater risk of morbidity, mortality as well as increase the rate of HIV transmission and health care costs. Nonretained HIV patients had an estimated rate of 6.6 transmissions per 100 person-years, compared with individuals engaged in the care.29

Drug substitution history is negatively associated with viral re-suppression. Frequent first-line antiretroviral drug substitution leads to reduction of subsequent treatment options and enforces reuse of previously substituted drugs. Consequently, there will be an increase in the chance of drug resistant and fail to re-suppress the viral load, especially in area where drug resistance test not yet implemented while drug substation. In second-line antiretroviral therapy, NRTI backbone drug substituted in the same class drug, which may be previously used.4,16 Hence, appropriate drug selection at the commencement of first-line antiretroviral therapy had a vital role on the effectiveness of subsequent therapy.

Similarly, anti-TB treatment and viral re-suppression were also inversely associated, which is consistent with a study conducted in South Africa.30 This association may be explained by the occurrence of infection (tuberculosis) which will flare-up the viral replication. Furthermore, there may be an interaction of anti-TB treatment drugs and second-line antiretroviral therapy; rifampicin is a potent cytochrome P450 3A4 liver enzyme inducer, which significantly reduces the serum levels of the PI drugs and consequently it reduces the rate of viral re-suppression. According to WHO- 2016 and national consolidate ART guidelines, for TB–HIV co-infected patients the dose of lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) should be adjusted; doubling the daily dose (ie LPV/r 800 mg/200 mg twice daily) or a super-boosted dose of RTV (ie LPV/r 400 mg/400 mg twice daily).4,16 However, this may also lead to drug intolerance and poor medication adherence. In line with this, a cohort study done in South Africa on adverse drug (ADR) reaction revealed that patients with poor health at the time of switch were at a high risk of ADR when receiving second-line therapy.31

Having high viral load at the commencement of second-line antiretroviral therapy is inversely related to viral re-suppression. This finding is also supported by many studies.7,9,10,13,25,32,33 Hence, switching to second-line therapy may not be a warranty for viral re-suppression for patients with high viral set point. It requires further close monitoring and strengthening of the implementation of enhanced adherence counseling for such type clients.

Delayed regimen switch after the first virological failure is associated with poor treatment outcomes. This finding was consistent with a prospective study conducted in South Africa.12 According to WHO-2016 and national consolidated ART guidelines, a patient should be switched to next level therapy when having two consecutive viral load measurements greater than 1000 copies/mL three months apart, with enhanced adherence support following the first viral load test.4,16 Failure to switch timely (ie, at three months after EAS) will give sufficient time for viral replication, development of resistance strain, which result in poor treatment outcomes. Studies done in Africa showed that delay between first virological failure and commencement of second-line therapy significantly related to poor immunological and virological outcomes as well as increased opportunity infection and mortality.34–36 Delay in therapy switch may be related to an individual, health professional, or health facility factors, which may require further investigation.

Being ambulatory, bedridden, and lower CD4 cell count at therapy switch had an increased risk of loss to follow up and death. This finding was consistent with the studies done in Ethiopia on patients on first-line therapy.8,10,25,32,37 Hence, accessing routine viral load monitoring for early diagnosis of treatment failure will increase the probability of patient retention on care, instead of waiting until immunological failure or clinical advancement. This association may be explained by poor immunological and clinical condition can easily lead to drug intolerance as well as poor drug compliance and this may further contribute poor treatment outcomes and failed to retained on care.

Similarly, patients with virological failure while on second-line treatment were also at increased risk of attrition, which is supported by a retrospective cohort study done in South Africa.8 Virally suppressed patients would have a stable clinical condition, feel self-control, and had better perceived quality of life that prolongs the chance of staying on care. This result implies that conducting routine viral load monitoring had a key role in program evaluation besides showing the success of treatment. Hence, striving to achieve the third 95 is one means of reducing patient attrition.

Strengths of the Study

First, the study is the first of its kind in Ethiopia to provide first-hand information to improve the outcomes of patients on second-line therapy. Second, it was conducted on a large sample size as well as used different data sources (chronic HIV follow up form, ART registration book, and SMART care electronic database) that increases consistency as well as minimizes incompleteness.

External validity: the finding of this research can be also extrapolated in other low income countries' setting where they implement similar WHO treatment modality, outcome ascertainment.38

Limitation of the Study

It failed to collect and analyze data on behavioral, social, and psychological factors as well as facility level determinants of viral re-suppression and attrition from care. Further, this study was unable to get and consider other clinical profiles like comorbidities, organ function results, and drug resistance test at time of therapy switch. All the above limitations were due to the nature of study design. Therefore, confounding through the unmeasured covariates need to be considered while interpreting the reported associations.

Conclusion

A significant number of patients had failed to achieve viral re-suppression and to retain on care after enrollment to second-line antiretroviral program. Most identified factors related to patient monitoring and clinical profiles. Hence, patient center interventions should be crafted and implanted on the identified predictors.

Abbreviations

ART, antiretroviral therapy; PLHIV, people living with HIV; VL, viral load; NRTIs, Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors; NNRTIs, Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors; INSTIs, Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors; PIs, Protease Inhibitors; DTG, Dolutegravir; 3TC, Lamivudine; ABC, Abacavir; AZT, Zidovudine; TDF, Tenofovir; EFV, Efavirenz; NVP, Nevirapine; LPV/r, Lopinavir/ritonavir; ATV/r, Atazanavir/ritonavir; BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; ADR, adverse drug reaction; INH, Isoniazid preventive therapy; MRI, Medical Record Number; DHIS2, District health information system; AHR, adjusted hazard ratio.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was secured from Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Bahir Dar University, College of Medicine and Health Science with reference number 00224/2020. Further, authorization was obtained from Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital in order to use of anonymized data. Besides, the confidentiality of obtained information assurance made by using code numbers rather than personal identifiers and by keeping the checklist locked. Since we used secondary sources, informed consent was waived that approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Bahir Dar University, College of Medicine and Health Science.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Bahir Dar University, College of Medicine and Health Science, School of Public Health, Institutional Review Board (IRB) for giving a timely ethical permission and unconditional support. We also acknowledge Dessie Comprehensive Specialized Hospital administrators and staffs for providing us permission to conduct the study as well as data collectors who collected the data in the era of COVID 19. Fentie Ambaw received support from AMARI (African Mental Health Research Initiative), which is funded through the DELTAS Africa Initiative (DEL-15-01).

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, agreed to the submitted journal, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research supported by Bahir Dar University College of Medicine and Health Science, School of Public Health. The funding body had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. UNAIDS/WHO. Global- HIB/AIDS Statistics, Fact Sheet. Vol. 3. UNAIDS; 2020.

2. Estill J, Ford N, Salazar-vizcaya L, et al. The need for second-line antiretroviral therapy in adults in sub-Saharan Africa up to 2030: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet HIV. 2016;3018(16):1–8. doi:10.1016/S2352-3018(16)00016-3

3. Elvstam O, Medstrand P, Yilmaz A, Isberg PE, Gisslen M, Bjorkman P. Virological failure and all-cause mortality in HIV-positive adults with low-level viremia during antiretroviral treatment. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):1–15. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0180761

4. WHO. The use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection; 2016: 99–152, 402. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/208825/9789241549684_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

5. WHO. Ethiopia HIV Country Profile: 2016 WHO/HIV/2017. WHO; 2017.

6. Long L, Fox M, Sanne I, Rosen S. The high cost of second-line antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS in South Africa. AIDS. 2010;24(6):915–919. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283360976

7. Mocroft A, Phillips AN, Miller V, et al. The use of and response to second-line protease inhibitor regimens: results from the EuroSIDA study. AIDS. 2001;15(2):201–209. doi:10.1097/00002030-200101260-00009

8. Gumede SB, Fischer A, Venter WDF, Lalla-Edward ST. Descriptive analysis of World Health Organization-recommended second-line antiretroviral treatment: a retrospective cohort data analysis. South African Med J. 2019;109(12):919–926. doi:10.7196/SAMJ.2019.v109i12.013895

9. Chakravarty J, Sundar S, Chourasia A, et al. Outcome of patients on second line antiretroviral therapy under programmatic condition in India. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):1. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-1270-8.

10. Nsanzimana S, Semakula M, Ndahindwa V, et al. Retention in care and virological failure among adult HIV+ patients on second-line ART in Rwanda: a national representative study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-3934-2

11. Stockdale AJ, Saunders MJ, Boyd MA, et al. Effectiveness of protease inhibitor/nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based second-line antiretroviral therapy for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(12):1846–1857. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1108

12. Fox MP, Ive P, Long L, Maskew M, Sanne I. High rates of survival, immune reconstitution, and virologic suppression on second-line antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. Epidemilog Soc Sci. 2010;53(4):500–506.

13. Desai M, Dikshit R, Patel D, Shah A. Early outcome of second line antiretroviral therapy in treatment-experienced human immunodeficiency virus positive patients. Perspect Clin Res. 2013;4(4):215. doi:10.4103/2229-3485.120170

14. Johnston V, Cohen K, Wiesner L, et al. Viral suppression following switch to second-line antiretroviral therapy: associations with nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor resistance and subtherapeutic drug concentrations prior to switch. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(5):711–720. doi:10.1093/infdis/jit411

15. Ferradini L, Ouk V, Segeral O, et al. High efficacy of lopinavir/r-based second-line antiretroviral treatment after 24 months of follow up at ESTHER/Calmette Hospital in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14(1):1–7. doi:10.1186/1758-2652-14-14

16. Ethiopia Federal Ministry of Health. National consolidated guidelines for comprehensive HIV prevention, care and treatment. 2018: 1–238.

17. Tsegaye AT, Wubshet M, Awoke T, Addis Alene K. Predictors of treatment failure on second-line antiretroviral therapy among adults in northwest Ethiopia: a multicentre retrospective follow-up study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e012537. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012537

18. Seid A, Niguss Cherie KA, Ahmed K. Determinants of virologic failure among adults on second line antiretroviral therapy in Wollo, Amhara Regional State, Northeast Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS Res Palliat Care. 2020;12:697–706. doi:10.2147/HIV.S278603

19. Worku ED, Asemahagn MA, Endalifer ML. Epidemiology of HIV infection in the Amhara region of Ethiopia, 2015 to 2018 surveillance data analysis. HIV/AIDS Res Palliat Care. 2020;12:307–314. doi:10.2147/HIV.S253194

20. EPHI. Ethiopian Public Health Institution National HIV Reference Laboratory. EPHI; 2016.

21. Medicne A societ laboratory. National review on HIV viral load testing and early infant diagnosis in Ethiopia; 2020. Available from: https://aslm.org/news-article/national-review-meeting-hiv-viral-load-testing-early-infant-diagnosis-ethiopia/.

22. WHO. The Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection. WHO; 2016.

23. Onoya D, Nattey C, Budgell E, et al. Predicting the need for third-line antiretroviral therapy by identifying patients at high risk for failing. Clin Epidemiol Res. 2017;31(5):205–212.

24. Collier D, Iwuji C, Derache A, et al. Virological outcomes of second-line protease inhibitor – based treatment for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in a high-prevalence rural South African setting: a competing-risks prospective cohort analysis. Clin Infect Dis MAJOR Artic Virol. 2017;64(8):1–11.

25. Shearer K, Evans D, Moyo F, et al. Treatment outcomes of over 1000 patients on second-line, protease inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy from four public-sector HIV treatment facilities across Johannesburg, South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22(2):221–231. doi:10.1111/tmi.12804

26. UNAIDS. 90-90-90An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic; 2014: 40. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en.pdf.

27. Mwasakifwa GE, Moore C, Carey D, et al. Relationship between untimed plasma lopinavir concentrations and virological outcome on second-line antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2018;32(3):357–361. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000001688

28. Thu N, Kyaw T, Kumar AMV, et al. Long-term outcomes of second-line antiretroviral treatment in an adult and adolescent cohort in Myanmar. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1290916. doi:10.1080/16549716.2017.1290916

29. Li Z, Purcell DW, Sansom SL, Hayes D, Hall HI. Vital signs: HIV transmission along the continuum of care — United States, 2016. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(11):267–272.

30. Collier D, Iwuji C, Derache A, et al. Virological outcomes of second-line protease inhibitor-based treatment for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in a high-prevalence Rural South African setting: a competing-risks prospective cohort analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(8):1006–1016. doi:10.1093/cid/cix015

31. Onoya D, Hirasen K, Berg L, Van Den MJ, Long LC, Fox MP. Adverse drug reactions among patients initiating second ‑ line antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. Drug Saf. 2018;41(12):1343–1353. doi:10.1007/s40264-018-0698-3

32. Häggblom A, Santacatterina M, Neogi U, et al. Effect of therapy switch on time to second-line antiretroviral treatment failure in HIV-infected patients. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):1–14. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0180140

33. Thao VP, Quang VM, Wolbers M, et al. Second-line HIV therapy outcomes and determinants of mortality at the largest HIV referral center in Southern Vietnam. Med obs study. 2015;94(43)1–8, doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000001715.

34. Ssempijja V, Nakigozi G, Chang L, et al. Rates of switching to second-line antiretroviral therapy and impact of delayed switching on immunologic, virologic, and mortality outcomes among HIV-infected adults with virologic failure in Rakai, Uganda. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:1–10.

35. Murphy RA, Court R, Maartens G, Sunpath H. Second-line antiretroviral therapy in Sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Res Human Retroviruses. 2017;33(12):1181–1184. doi:10.1089/aid.2017.0134

36. Petersena ML, Linh Trana EH, Gengb SJ. Delayed switch of antiretroviral therapy after virologic failure associated with elevated mortality among HIV-infected adults in Africa. NIH Public Access. 2015;28(14):2097–2107.

37. Moges NA, Olubukola A, Micheal O, Berhane Y. HIV patients retention and attrition in care and their determinants in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(439):1–24.

38. Findley MG, Denly M. External validity. Ann Rev Polit Sci. 2020;24:365–393.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.