Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 13

Quetiapine monotherapy versus placebo in the treatment of children and adolescents with bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Authors Maneeton B , Putthisri S, Maneeton N , Woottiluk P, Suttajit S, Charnsil C, Srisurapanont M

Received 4 September 2016

Accepted for publication 24 January 2017

Published 4 April 2017 Volume 2017:13 Pages 1023—1032

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S121517

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Wai Kwong Tang

Benchalak Maneeton,1 Suwannee Putthisri,2 Narong Maneeton,1 Pakapan Woottiluk,3 Sirijit Suttajit,1 Chawanun Charnsil,1 Manit Srisurapanont1

1Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, 2Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, 3Psychiatric Nursing Division, Faculty of Nursing, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand

Background: Some studies have indicated the efficacy of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar depression in adult patients. However, its efficacy has been not shown in child and adolescent patients.

Objective: This systematic review purposefully determined the efficacy and acceptability of quetiapine in the treatment of children and adolescents with bipolar depression.

Data sources: A database search of EMBASE, PubMed, CINAHL, and Cochrane Controlled Trials Register was carried out in March 2016. All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of bipolar depression in children and adolescents were considered for inclusion in this review.

Study eligibility criteria, participants, and interventions: RCTs of quetiapine in the treatment of child and adolescent patients with bipolar depression with end point outcomes were included in this study. Languages were not limited.

Study appraisal and synthesis methods: The full-text versions of relevant clinical studies were thoroughly examined and extracted. The primary efficacy of outcome was measured by using the pooled mean-changed scores of the rating scales for bipolar depression. However, the response and remission rates were also measured.

Results: A total of 251 randomized patients in the three RCTs of quetiapine versus placebo in the treatment of bipolar depression for children and adolescents were eligible in this review. The pooled mean-changed score of the quetiapine-treated group was not greater than that of the placebo-treated group. Similarly, the pooled response and remission rates were not different between the two groups. The pooled overall discontinuation rate and the discontinuation rate due to adverse events were not different between the two groups.

Limitations: Limited studies were eligible in this review.

Conclusion: According to the findings in this review, quetiapine may not be efficacious in the treatment of bipolar depression in children and adolescents. Its acceptability, however, was comparable to a placebo. Therefore, the use of quetiapine in children and adolescents with bipolar depression is not recommended. Further well-defined clinical studies should be performed to confirm these outcomes.

Keywords: monotherapy, depressive episodes, pharmacological treatment, Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised, CDRS-R

Introduction

Bipolar depression is considered as a major depressive episode of bipolar I or II disorders. Patients with bipolar I or II disorders often experience depressive symptoms, including time to clinical remission longer than either hypomanic or manic episodes.1–3 Depressive episodes in bipolar disorders are associated with significant impairment of various occupational, academic, and social functioning, negative effects on the quality of life, and mortality of children and adolescents.4,5 However, a limited number of clinically controlled studies indicated the efficacy of pharmacological treatment for children and adolescents diagnosed with bipolar disorder.6–8

Quetiapine antagonizing to serotonergic (5-HT1A and 5-HT2A), dopaminergic (D1 and D2), and histamine (H1) receptors and adrenergic (α1 and α2) receptors has efficacy in the treatment of schizophrenia,9 major depressive disorder (MDD),10 generalized anxiety disorder,11 and bipolar disorder, including its depressive episode.12 A previous study suggests that an adjunctive quetiapine treatment can alter the sleep architecture in patients with MDD or bipolar depression.13 In addition, it also has an active metabolite, norquetiapine (N-desalkyl quetiapine), which has a high affinity for norepinephrine transporters and partially agonizes to serotonin 5-HT1A receptors.14 Hence, the efficacy of quetiapine in ameliorating depressive symptoms in adults with unipolar and bipolar depression may be associated with antagonizing at 5-HT2A, α2b adrenergic, and D2 receptors and agonizing at a 5-HT1A receptor and its effect on sleep architecture.13,15

Although some randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have shown the efficacy of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar depression in children and adolescents,6–8 each study had limited sample sizes. A previous review of quetiapine in bipolar depression was performed without separate synthesis of outcomes of the child and adolescent population, and one of the three RCTs of quetiapine versus placebo in the treatment of bipolar depression for children and adolescents was not included in such a review.12 Consequently, a statistical method for possibly determining the true effect size, meta-analysis, may examine quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar depression in children and adolescents in terms of efficacy and acceptability.

This study purposefully and systematically reviewed the efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of quetiapine monotherapy for acute depressive episodes in children and adolescents with bipolar I and II disorders based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). In this review, efficacy was measured by using the pooled mean-changed scores of standardized rating scale for depressive symptoms, response rate, and remission rate. In addition, acceptability and tolerability were determined by the overall discontinuation rate and the discontinuation rate due to adverse events, respectively. Only such RCTs were eligible in this review.

Methods

Types of included trials

Any relevant RCTs that met the inclusion criteria were eligible.

Types of participants

All children and adolescents, up to18 years of age and diagnosed with bipolar I or II disorder with depressive episodes utilizing either the ICD or DSM criteria, were included.

Types of interventions

Quetiapine as monotherapy was compared with a placebo. The doses, forms, and frequency of therapy were not limited.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the mean-changed score of a standardized depressive rating scale (Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised, CDRS-R).16,17

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures included:

- Response and remission rate defined by each trial

- Clinical Global Impression–Bipolar Version Severity (CGI-BP-S)

- Discontinuation rates

- Overall discontinuation rate

- Discontinuation rate due to adverse events

Information sources

The databases, including EMBASE, PubMed, CINAHL, and Cochrane Controlled Trials Register databases, were searched in March 2016. As the first publication of quetiapine administration commenced in 1991 in the PubMed, searching the publications was planned to start from January 1991 to March 2016. All searches were restricted to trials conducted in humans. In addition, the databases of ClinicalTrials.gov, EU Clinical Trials Register (EU-CTR), and AstraZeneca Clinical Trials were also searched. The relevant references of any article provided by any method were assessed. All relevant RCTs were considered. However, languages in each study were not limited.

Searches

To sensitize the optimal identification of the RCTs, the searching method for PubMed was limited to the following words and phrases: ([quetiapine] OR [seroquel]) AND ([Bipolar depression] OR [BD]). This similar searching strategy was used in the rest of the databases.

Study selection

To decide whether each study conformed to the eligibility criteria described earlier, inspection of all abstracts derived from those electronic databases was individually conducted by two reviewers (NM and BM). Then, the full-text versions of the relevant articles were collected and individually examined by the reviewers. If disputes occurred between the two reviewers, a conclusion was achieved by consensus.

Data collection process

Initially, data of the full-version articles were extracted and entered into the extraction form developed by the first reviewer (NM). Subsequently, the second reviewer (BM) meticulously rechecked the extracted data. Again, all disputes between two reviewers were also resolved by consensus. If those disagreements between two reviewers were still unresolved, the third reviewer (MS) would make the decision.

Data items

The extraction data gathered from the clinical studies comprised the following: 1) important information used for evaluating the study quality; 2) basic characteristic data including population, diagnostic criteria, study designs, and eligible/ineligible criteria; 3) forms, doses, and treatment duration of quetiapine vs placebo; 4) interesting outcomes; and 5) intention-to-treat outcomes.

Risk of bias in individual studies

The internal validity (quality) assessments of the included clinical trials were carried out by two reviewers (NM and BM). According to the quality assessment of Cochrane Collaboration, the risk of bias was examined, including 1) sequence generation (randomization); 2) allocation concealment; 3) blinding of participants, personnel, and outcomes; 4) incomplete outcome data; 5) selective outcome reporting; and 6) other biases. In addition, outcome quality was evaluated by using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.18

Summary measures

The interesting outcomes were efficacious, acceptable, and tolerable. The end point or the mean-changed scores rated on the standardized depressive scale and the response rate defined by any set of criteria were considered as a treatment efficacy. Although acceptability and tolerability have been interchangeably applied, each term has its specific definition. Like the previous meta-analysis, the overall discontinuation rate, including rate of adverse events,19 and the discontinuation rate due to adverse events, related to only side effects of the medications,20 were considered as an acceptability and tolerability, respectively.

Statistical analysis and synthesis of results

Basically, a weighted mean difference (WMD) or a standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence interval (CI) is estimated by the mean difference between the comparison groups divided by an estimate of the within-group standard deviation (SD). Mean difference, with 95% CI, was applied for synthesis of the continuous outcomes. When the same outcomes are measured by various rating scales across studies, the direct comparison or combination of such study results was implausible. Hence an SMD, a statistic summary method that can be used when the same outcome is measured in a variety of ways, is a reasonable measurement of comparison or combination for those findings. When a similar rating scale was used, a WMD, directly comparing, or combining the study results, was applied. Since all included clinical trials used a similar rating scale to assess the same outcomes, the WMD was applied for estimating the efficacy of quetiapine by using all of the continuous data. If the SD of the changed mean scores was not available, it was estimated by using any of the statistical analyses or by direct substitution.21 The statistical method for combining the results of multiple studies by an inverse variance for the estimated measure effect, which weighed the influence of each study, was used to calculate the pooled mean-changed scores with 95% CIs.18

Synthesis of dichotomous outcomes used the relative risk (RR), with the 95% CI. If the RR was exactly 1, it indicated that the differences in the outcomes did not take place between the intervention and control groups. When the RR was > or <1, it suggested that the intervention, respectively, increased or decreased the risk of the outcomes. In this review, the RRs were applied to compare the response rates, the remission rates, the overall discontinuation rates, and the discontinuation rates due to adverse events between the two groups. The Mantel–Haenszel technique was applied to calculate all pooled RRs of dichotomous data with 95% CIs.18

In a systematic review, the outcomes are synthesized by using either the fixed- or random-effects model. When relying on the fixed-effects model, all of the eligible studies expected that the true effect size was the same in all trials, and the summary effect was the estimation of the common effect size. Hence, after the individual study was weighted, the outcomes of smaller studies could be ignored due to the better outcomes regarding the same effect size in the larger studies provided. In this event, a fixed-effects model may be used. In fact, the assumption of one true effect size is hardly plausible. Even if all the included studies were relatively homogenous, it was not possible to conclude that they were absolutely identical. By this reason, a random-effects model, assuming that the true effect size varies across the studies, was applied to synthesize all the outcomes in this review. The RevMan 5.1 was applied through synthesis to all of the results in this systematic review.

Risk of bias across studies

If possible, a funnel plot is used for evaluating the reporting bias. A funnel plot is a simple scatter plot of the treatment effect estimated from each study against a measure of each study’s size. If bias does not occur, the plot should resemble a symmetrical inverted funnel.22

Test of heterogeneity

A test of heterogeneity can examine the similarities of clinical outcomes. When the test was performed in this systematic review, we hypothesized that the effect size had differences because of the differences in the quality of the methodology in each study. The findings of all studies were determined to whether they were higher and different from the anticipated outcomes by chance alone. To evaluate those findings, we reviewed them by showing them as graphs and also used the test of heterogeneity. In the case of an I2 of 50% or more, those findings were noted as having significance of heterogeneity.

Results

Study selection

According to searching such databases, there was a total of 160 citations (EMBASE =35, PubMed =34, CINAHL =15, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register =68, ClinicalTrials.gov =5, and EU-CTR =3; Figure 1). After the duplicates were removed, 129 citations persisted. When their titles and abstracts were assessed, seven citations still met the eligibility criteria. Therefore, full articles of seven citations were examined. Of the seven citations, four were excluded from this review since they were studied in an adult population.23–26 Consequently, three clinical trials were included in this meta-analysis.27–36 However, a relevant or unpublished study fitting the included criteria was not detected.

| Figure 1 Flow diagram of the study. |

Study characteristics

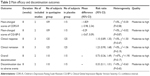

All eligible studies included patients with bipolar I or II associated with depressive episode with a CDRS-R score of ≥40–45. The duration of included clinical trials was 8 weeks. Each randomized patient was assigned to receive either quetiapine or placebo treatment. The response criterion was similar in each of the eligible studies. The dose of quetiapine was 150–600 mg/day (Table 1). The demographic and basic characteristics of the quetiapine-treated group vs the placebo-treated group were generally well matched across the three studies.6–8

A total of 251 randomized participants were enrolled in this review. All the included patients met a depressive episode of either bipolar I or II disorder based on the criteria of the DSM, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). The mean (SD) ages of the quetiapine-treated group and the placebo-treated group were 14.5 (2.3) years and 14.2 (2.1) years, respectively. The basic characteristics of three eligible trials have been presented in Table 1.

Since all eligible studies reported the scores of the CDRS-R as a measure of depressive severity, the WMDs of the mean-changed scores could be applied to estimate and synthesize the outcome. In addition, these studies also reported the remission, response, and discontinuation rates.

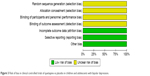

Risk of bias within studies

The random consequence generation, allocation concealment, binding of participants, and personnel and binding of outcome assessment were not clearly explained in all eligible trials (Figures 2 and 3). Two studies used the intention-to-treat analysis,6,7 and one used the modified intention-to-treat analysis.8 Based on the GRADE assessment, all outcome qualities were moderate to high (Table 2).

| Figure 3 Risk of bias in clinical controlled trials of quetiapine vs placebo in children and adolescents with bipolar depression. |

Synthesis of results

Efficacy

The significance of heterogeneity was not found in the WMDs for the pooled mean-changed scores of the CDRS-R and the CGI-BP-S and response and remission rates. The pooled WMD for the mean-changed score of the CDRS-R total and the CGI-BP-S scores in the quetiapine- and placebo-treated groups had no significant differences with WMD (95% CI) of −1.82 (−5.98, 2.34), I2=0% and −0.29 (−0.67, 0.09), I2=0%, respectively (Figures 4 and 5). Similarly, the overall pooled response and remission rate between the two groups were not also significantly different with RRs (95% CI) of 1.10 (0.89, 1.35), I2=0% and 1.23 (0.90, 1.68), I2=0%, respectively (Figures 6 and 7).

Overall discontinuation rate (acceptability)

A significance of heterogeneity was not noted in the overall discontinuation rate. Since the pooled overall discontinuation rate was not significantly different between the two groups with RRs (95% CI) of 0.73 (0.36, 1.49), I2=47%, it indicated that acceptability of quetiapine was not better than that of placebo in the treatment of children and adolescents with bipolar depression.

Discontinuation rate due to adverse events (tolerability)

The significance of heterogeneity was not found in the discontinuation rate due to adverse events between the two groups. The pooled discontinuation rate due to adverse events of the quetiapine- and placebo-treated groups having no significant difference (RR [95% CI] of 0.33 [0.11, 1.01], I2=0%) indicated that the tolerability of quetiapine was comparable with placebo in the treatment of children and adolescents with bipolar depression.

Risk of bias across studies

If a systematic review includes the RCTs of <10 studies, a funnel plot examining the publication bias may not have enough power to identify the chances of real asymmetry occurring.22 Hence, the test of funnel plot was not carried out in this review since this review included only three studies.

Discussion

The findings from this systematic review suggested that quetiapine monotherapy as measured by the mean-changed score and response rate was not effective in the acute treatment of bipolar depression in children and adolescents. Similarly, its remission rate was not higher than that of placebo. Quetiapine monotherapy could not reduce the severity of depressive symptoms measured by clinical global impression. In addition, its acceptability and tolerability were also not better than those of placebo.

The previous systematic review found that quetiapine monotherapy was an effective treatment in adult patients with bipolar depression,12 while our findings did not support those results. The different outcomes between adults and child and adolescent populations may be caused by either high comorbid psychopathology, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder,37 in children and adolescents with bipolar I or II disorder associated with poor response treatment or methodological limitations of the included studies.6–8

Based on the previous evidence, antidepressant effect is associated with the norquetiapine/quetiapine ratio,38 quetiapine extended release may have a different antidepressant profile compared with quetiapine immediate release. In this review, two of three included studies administered immediate-release quetiapine which may be associated with the negative outcomes. Further studies should be carried out to confirm those results.

Recent evidence suggested that the acceptability and tolerability of quetiapine was not higher than placebo and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors,11 which was compatible with our findings. The patients have experienced some adverse events such as headache, sedation, dizziness, somnolence, diarrhea, fatigue, and nausea.6,8 In addition, previous studies have supported that the development of obesity and metabolic syndrome is possibly associated with the use of second-generation antipsychotics, including quetiapine,39,40 while obesity is one of the risk factors for the development of rapid cycling in patients with bipolar disorder.41 For this reason, use of quetiapine should be not recommended in those patients.

This systematic review had some limitations. First, since there were a small number of included studies in this review, the pooled sample size may be affected. Further reviews including augmentation trials with quetiapine in such patients may be useful. Second, the eligible trials were funded by a patent-holding company for quetiapine. Interpretation of those results should be viewed with caution. Third, this review did not include patients with bipolar depression and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder diagnosed by using the DSM, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Fourth, this review used narrow search terms as a previous review;12 therefore, the sensitivity of searching possibly decreased. Finally, selection, detection, and reporting biases of all the included studies were performed and the test of funnel plot to assess an asymmetry was unable to be carried out because of a limited number of eligible clinical studies.22 Hence, in this review, publication bias was impossible to be excluded.

Conclusion

According to the evidence from this review, quetiapine as monotherapy is inefficacious in the acute treatment of children and adolescents with bipolar depression. In addition, its acceptability and tolerability were not better than those of placebo. Hence, the use of quetiapine in such patients should be avoided. Further well-defined studies should be performed to validate these findings.

Acknowledgments

This review received financial support from Chiang Mai University, Thailand. The authors intend to acknowledge that, in their opinion, the first two authors should be regarded as joint first authors.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

BM has received honoraria and/or travel reimbursement from Lundbeck and Pfizer. NM has received travel reimbursement from Lundbeck and Pfizer. SS has received honoraria and/or research grants from Janssen-Cilag, Thai-Otsuka, Lundbeck, and AstraZeneca. CC received honoraria and/or travel reimbursement from Janssen-Cilag, GlaxoSmithKline, and Thai-Otsuka. MS has received honoraria, consultancy fees, research grants, and/or travel reimbursement from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Janssen-Cilag, Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck, Thai-Otsuka, Sanofi-Aventis, and Servier. SP and PW report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Hlastala SA, Frank E, Mallinger AG, Thase ME, Ritenour AM, Kupfer DJ. Bipolar depression: an underestimated treatment challenge. Depress Anxiety. 1997;5(2):73–83. | ||

Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(6):530–537. | ||

Post RM, Denicoff KD, Leverich GS, et al. Morbidity in 258 bipolar outpatients followed for 1 year with daily prospective ratings on the NIMH life chart method. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(6):680–690. quiz 738-9. | ||

Goldstein TR, Birmaher B, Axelson D, et al. History of suicide attempts in pediatric bipolar disorder: factors associated with increased risk. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(6):525–535. | ||

Gomes BC, Kleinman A, Carvalho AF, et al. Quality of life in youth with bipolar disorder and unaffected offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2016;202:53–57. | ||

DelBello MP, Chang K, Welge JA, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of quetiapine for depressed adolescents with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(5):483–493. | ||

Chang K, Delbello M, Chu WJ, et al. Neurometabolite effects of response to quetiapine and placebo in adolescents with bipolar depression. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(4):261–268. | ||

Findling RL, Pathak S, Earley WR, Liu S, DelBello MP. Efficacy and safety of extended-release quetiapine fumarate in youth with bipolar depression: an 8 week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24(6):325–335. | ||

Srisurapanont M, Maneeton B, Maneeton N. Quetiapine for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2:CD000967. | ||

Maneeton N, Maneeton B, Srisurapanont M, Martin SD. Quetiapine monotherapy in acute phase for major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:160. | ||

Maneeton N, Maneeton B, Woottiluk P, et al. Quetiapine monotherapy in acute treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:259–276. | ||

Suttajit S, Srisurapanont M, Maneeton N, Maneeton B. Quetiapine for acute bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:827–838. | ||

Gedge L, Lazowski L, Murray D, Jokic R, Milev R. Effects of quetiapine on sleep architecture in patients with unipolar or bipolar depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6:501–508. | ||

Jensen NH, Rodriguiz RM, Caron MG, Wetsel WC, Rothman RB, Roth BL. N-desalkylquetiapine, a potent norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and partial 5-HT1A agonist, as a putative mediator of quetiapine’s antidepressant activity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(10):2303–2312. | ||

Yatham LN, Goldstein JM, Vieta E, et al. Atypical antipsychotics in bipolar depression: potential mechanisms of action. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(suppl 5):40–48. | ||

Poznanski EO, Cook SC, Carroll BJ. A depression rating scale for children. Pediatrics. 1979;64(4):442–450. | ||

Poznanski EO, Cook SC, Carroll BJ, Corzo H. Use of the Children’s Depression Rating Scale in an inpatient psychiatric population. J Clin Psychiatry. 1983;44(6):200–203. | ||

Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2009. Available from http://training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed January 25, 2017. | ||

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):746–758. | ||

Papakostas GI. Tolerability of modern antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(suppl E1):8–13. | ||

Wiebe N, Vandermeer B, Platt RW, Klassen TP, Moher D, Barrowman NJ. A systematic review identifies a lack of standardization in methods for handling missing variance data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(4):342–353. | ||

Sterne JAC, Egger M, Moher D [homepage on the Internet]. Addressing reporting biases. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2009. (Updated March 2011). Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. Accessed January 25, 2017. | ||

Calabrese JR, Keck PE Jr, Macfadden W, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I or II depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(7):1351–1360. | ||

Endicott J, Rajagopalan K, Minkwitz M, Macfadden W, Group BS. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar I and II depression: improvements in quality of life. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;22(1):29–37. | ||

Endicott J, Paulsson B, Gustafsson U, Schioler H, Hassan M. Quetiapine monotherapy in the treatment of depressive episodes of bipolar I and II disorder: improvements in quality of life and quality of sleep. J Affect Disord. 2008;111(2–3):306–319. | ||

Thase ME, Macfadden W, Weisler RH, et al. Efficacy of quetiapine monotherapy in bipolar I and II depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study (the BOLDER II study). J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(6):600–609. | ||

A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of sustained-release quetiapine fumarate (SEROQUEL®) compared with placebo in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder; 2006. Available from: www.clinicaltrials.gov. NLM identifier: NCT00329264. Accessed April 21, 2015. | ||

Khan A, Joyce M, Atkinson S, Eggens I, Baldytcheva I, Eriksson H. A randomized, double-blind study of once-daily extended release quetiapine fumarate (quetiapine XR) monotherapy in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(4):418–428. | ||

Merideth C, Cutler AJ, She F, Eriksson H. Efficacy and tolerability of extended release quetiapine fumarate monotherapy in the acute treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized, placebo controlled and active-controlled study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(1):40–54. | ||

Bandelow B, Chouinard G, Bobes J, et al. Extended-release quetiapine fumarate (quetiapine XR): a once-daily monotherapy effective in generalized anxiety disorder. Data from a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;13(3):305–320. | ||

An international, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, active-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of sustained-release quetiapine fumarate (Seroquel SR™) in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder (SILVER); 2006. Available from: www.clinicaltrials.gov. NLM identifier: NCT00322595. Accessed April 21, 2015. | ||

A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, active-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of sustained-release quetiapine fumarate (SEROQUEL®) compared with placebo in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder; 2006. Available from: www.clinicaltrials.gov. NLM identifier: NCT00329446. Accessed April 21, 2015. | ||

Merideth C, Cutler A, Neijber A, She F, Eriksson H. Extended release quetiapine fumarate monotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder (gad): a randomized, placebo and escitalopram-controlled study. World Psychiatry. 2009;8(suppl 1):215. | ||

Brawman-Mintzer O, Nietert PJ, Rynn M, Rickels K. Quetiapine monotherapy in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Paper presented at: 46th Annual NCDEU (New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit) Meeting 2006; Boca Raton, FL. | ||

Endicott J, Svedsater H, Locklear JC. Effects of once-daily extended release quetiapine fumarate on patient-reported outcomes in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2012; 8:301–311. | ||

Sheehan DV, Svedsater H, Locklear J, Eriksson H. Effects of extended release quetiapine fumarate on long-term functioning and sleep quality in patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) [conference abstract]. Paper presented at: 163rd Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association 2010; New Orleans, LA; 2010. | ||

Geller B, Luby J. Child and adolescent bipolar disorder: a review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(9):1168–1176. | ||

Altamura AC, Moliterno D, Paletta S, et al. Effect of quetiapine and norquetiapine on anxiety and depression in major psychoses using a pharmacokinetic approach: a prospective observational study. Clin Drug Investig. 2012;32(3):213–219. | ||

Jalota R, Bond C, Jose RJ. Quetiapine and the development of the metabolic syndrome. QJM. 2015;108(3):245–247. | ||

Rojo LE, Gaspar PA, Silva H, et al. Metabolic syndrome and obesity among users of second generation antipsychotics: a global challenge for modern psychopharmacology. Pharmacol Res. 2015;101:74–85. | ||

Buoli M, Dell’Osso B, Caldiroli A, et al. Obesity and obstetric complications are associated with rapid-cycling in Italian patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2016;208:278–283. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.