Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 11

Quality of life of patients with schizophrenia treated in foster home care and in outpatient treatment

Authors Mihanović M, Restek-Petrović B, Bogović A, Ivezić E, Bodor D, Požgain I

Received 1 September 2014

Accepted for publication 9 December 2014

Published 5 March 2015 Volume 2015:11 Pages 585—595

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S73582

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Roger Pinder

Mate Mihanović,1,2 Branka Restek-Petrović,1,2 Anamarija Bogović,1 Ena Ivezić,1 Davor Bodor,1 Ivan Požgain3

1Psychiatric Hospital “Sveti Ivan”, Zagreb, 2Faculty of Medicine Osijek, Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, 3Department of Psychiatry, University Hospital Center Osijek, Osijek, Croatia

Background: The Sveti Ivan Psychiatric Hospital in Zagreb, Croatia, offers foster home care treatment that includes pharmacotherapy, group psychodynamic psychotherapy, family therapy, and work and occupational therapy. The aim of this study is to compare the health-related quality of life of patients with schizophrenia treated in foster home care with that of patients in standard outpatient treatment.

Methods: The sample consisted of 44 patients with schizophrenia who, upon discharge from the hospital, were included in foster home care treatment and a comparative group of 50 patients who returned to their families and continued receiving outpatient treatment. All patients completed the Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire on the day they completed hospital treatment, 6 months later, and 1 year after they participated in the study. The research also included data on the number of hospitalizations for both groups of patients.

Results: Though directly upon discharge from the hospital, patients who entered foster home care treatment assessed their health-related quality of life as poorer than patients who returned to their families, their assessments significantly improved over time. After 6 months of treatment, these patients even achieved better results in several dimensions than did patients in the outpatient program, and they also had fewer hospitalizations. These effects remained the same at the follow-up 1 year after the inclusion in the study.

Conclusion: Notwithstanding the limitations of this study, it can be concluded that treatment in foster home care is associated with an improvement in the quality of life of patients with schizophrenia, but the same was not observed for the patients in standard outpatient treatment. We hope that these findings will contribute to an improved understanding of the influence of psychosocial factors on the functioning of patients and the development of more effective therapeutic methods aimed at improving the patients’ quality of life.

Keywords: psychosocial treatment, SF-36

Introduction

Although the evaluation of psychiatric treatments in the past was primarily focused on reducing the psychopathological symptoms, in recent years, the significance of the quality of life has become more prominent, as patients’ recovery also includes their reintegration into their family, work environment, and social life.1–3 The specific construct applied as a standard in the evaluation of treatments is health-related quality of life; it assesses the aspects of quality of life for which it is assumed that the treatment has a direct effect. This is an assessment of the individuals’ functionality, specifically with respect to their mental health (eg, their limitations in professional and social functioning that can be attributed to mental difficulties, as opposed to limitations that are the result of restricted bodily and social abilities).1,4

Quality of life, as a criterion of therapeutic effect, is particularly important for patients with schizophrenia because this is a disorder that negatively reflects on all aspects of life, demands long-term pharmacological and psychosocial treatment and rehabilitation, and leads to high health care costs. Indeed, research has shown that therapy directed only at psychopathological symptoms, primarily pharmacotherapy, is insufficient for success in the work place and in interpersonal relations, and for social functioning in general.5 In particular, therapy with antipsychotics can reduce positive symptoms and prevent relapses; however, it is less successful in addressing negative symptoms and cognitive impairments,6 and it is not significantly associated with improvements in patients’ social situation3 or with the subjective assessment of one’s own well-being.7 However, subjective experiences of quality of life influence motivation for treatment participation, pharmacotherapy adherence, and participation in psychosocial rehabilitation, thereby also influencing the outcome of treatment.1,8 Additionally, research has shown that the subjective assessment of health-related quality of life is a significant predictor of relapse in patients with schizophrenia9 and of suicide risk.10 Therefore, the recent practice guidelines and standards have recommended the use of multifaceted illness management programs consisting of different combinations of physical, psychological, and social interventions, with the goal of reducing patients’ symptoms and improving their functioning and quality of life in the longer term.6 It is suggested that psychosocial interventions can not only directly address a wide range of patients’ health needs but also provide a more cost-effective intervention than the standard treatment for schizophrenia.11

As a result of reforms in the psychiatric health care system and measures to improve mental health, in most developed countries, the focus has shifted from hospitals to the protection and improvement of mental health in the community.3 A process has been launched to reduce the number of hospital beds, to transform these wards into mental health centers, and to include patients in the community.12 Therefore, the noninstitutional health care of psychiatric patients has become increasingly popular in the past few decades,13 and clinical research has indicated that community-based psychosocial interventions can improve the long-term outcomes of patients with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses.11 With the deinstitutionalization of psychiatric health care, the concept of quality of life has become a relevant construct in studies on patients with schizophrenia, and there have been an increasing number of papers published on the subject.14–17 A literature review found a number of studies that addressed the quality of life of patients with schizophrenia receiving various types of health care (Table 1). The majority of findings suggest that the less restrictive is the environment, the more pronounced is the feeling of general well-being.18–23 This finding was also supported by Barry and Crosby24 and Barry and Zissi,25 who indicated an increased subjective quality of life with the transition from the hospital into the community. However, several studies did not find any differences in the quality of life between patients with schizophrenia, depending on the type of accommodation,26–29 whereas in two studies, patients treated in more restrictive settings expressed greater subjective satisfaction with their lives than did those living alone or with families.30,31

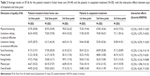

| Table 1 Summary of studies on the quality of life of patients with schizophrenia depending on their type of accommodation and treatment |

Therefore, the study results on the quality of life of patients with schizophrenia based on their type of living situation are inconsistent, and no definite conclusions on the advantages of individual types of living could be drawn. This might be due to the heterogeneity of the methods applied in different studies; that is, these studies examined the potential effects of different types of treatment or accommodation, the patients differed in the intensity of their symptoms, various aspects of quality of life were measured, and different ranges of scales were applied, which hinders the comparison of results. Moreover, the quality of life of patients largely relies on the social context, such as the national employment rate, the general standard of living, and the development of general and psychiatric health care.32 To provide a better understanding of the influence of different psychosocial factors on the functioning of psychiatric patients, it would be beneficial for future studies to focus more on specific types of accommodation/treatment and on more homogeneous patient groups while taking into account the broader sociocultural context.

With regard to the treatment of patients in foster home care, this type of outpatient psychiatric care is not often applied in the global psychiatric practice.12 The Sveti Ivan Psychiatric Hospital is the only psychiatric hospital in Croatia to enable the housing, treatment, and rehabilitation of psychiatric patients in foster home care as part of the sociotherapy program, based on the Belgian model applied in the city of Gheel.33 Housing in foster care is a specific and unique form of treatment. It is a continuation of treatment and psychosocial rehabilitation in the outpatient facility, though in a suitably protected environment. Thus, it represents a combination of inpatient and outpatient treatment, with organized programs of activities and continuous monitoring by the medical team, while staying in a family environment and participating in the local community. Moreover, this type of treatment makes it possible for patients who do not have their own families to experience family life and to experience all the psychosocial benefits that this type of environment affords in the context of reintegration, resocialization, and destigmatization.

The reasons for housing patients outside their own families are usually unfavorable financial and housing situations, an insufficiently supportive social environment, prejudice and negativist attitudes toward patients, disturbed family relationships, cohabitation with family members who also have mental illness, and difficulties with independent living.12,34,35 These are primarily for patients with a diagnosis of psychotic disorders or depressive disorders. Foster families aim to make it possible for patients to experience family life and a higher quality of life and care, depending on their needs.12,35 The objectives of this treatment and rehabilitation model are to prevent relapses and ensure a faster return to the family and the social community, to improve the social functioning and quality of life of the patient, to unburden hospital capacities, and to stimulate the development of noninstitutional health care for psychiatric patients by reducing the discrimination against patients and their families.34,35

Few evaluation studies conducted so far have yielded positive results on patients’ well-being and rehabilitation. Patients were actively engaged in occupational and recreational activities, their motivation for work increased, and they had richer social relationships.34 Additionally, treatment in foster home care had a positive effect on reducing the symptoms of schizophrenia,36 and the remissions lasted longer than for patients dismissed from the hospital.35 Concerning self-perceived quality of life, preliminary findings on 22 patients with schizophrenia showed a trend of improvement 6 months after being included in foster home care program.36 The only other study found on the treatment outcome of patients treated in foster home care was that of Linn et al.33 However, this study did not test the quality of life of patients, only their social functioning. Patients housed and treated in foster home care showed better social adaptations within the observed 4-month period than hospitalized patients.

The aim of this study is to compare the quality of life of patients with schizophrenia housed and treated in foster home care with patients who, after hospitalization, were included in an outpatient treatment while living with their primary or secondary families. The findings could enable a better understanding of the influence of psychosocial factors on the functioning of patients and the development of more effective outpatient therapeutic and rehabilitation methods aimed at improving patients’ quality of life and reducing stigmatization. Based on the findings of a few studies conducted so far, we predicted that patients in foster home care would report a higher quality of life than the group of outpatients.

Materials and methods

Participants

A total of 102 patients diagnosed with chronic paranoid schizophrenia participated in the study. The psychiatric diagnosis of the patients was determined by the attending psychiatrists by applying the semi-structured clinical interview according to the criteria of International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, tenth edition (ICD-10).37 All patients were in remission at the time of their inclusion in the study and received the appropriate low-to-medium dose maintenance antipsychotic therapy (risperidone, haloperidol, clozapine, olanzapine, fluphenazine; 300–600 mg chlorpromazine equivalents per day) that was regularly adjusted by the expert team that monitored their mental state. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Sveti Ivan Psychiatric Hospital, and all patients signed an informed consent form for participation. One group of participants consisted of 49 patients who, on the date of completing hospital treatment, were included in the program of housing, treatment, and psychosocial rehabilitation in foster home care. The second group comprised 53 patients who, after completing hospital treatment, returned to their primary or secondary families and continued receiving outpatient treatment with pharmacological therapy and occasional check-up exams by a psychiatrist. The patients in the second group, in terms of their sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, were similar to the patients treated in foster home care and served as the comparable group. In the first group, five patients did not complete the study because they left the housing and treatment in foster home care, and in the second group, three subjects did not remain in outpatient treatment until the end of the observed 1-year study period. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients who completed the study are shown in Table 2.

| Table 2 Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients treated in foster home care (n=44) and in outpatient treatment (n=50) |

Foster home care treatment

The treatment includes pharmacotherapy, group psychodynamic psychotherapy, family therapy, and work and occupational therapy. Patients are placed individually or in small groups in families primarily residing in rural areas, though in relatively close proximity to the hospital. The capacity of accommodation is 40 patients in ten homes. Members of the foster families are trained on mental disorders and ways to handle psychiatric patients, and a guidebook has also been written and published for them. The treatment is organized and implemented by a multidisciplinary team that includes a psychiatrist, senior nurse, occupational therapist, and social worker. Once a week, and more often if needed, a field team visits the patients.

Measure and procedure

To assess the quality of life of patients, the Croatian version of the Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36)38 was used. The SF-36 is a questionnaire of the self-assessment of health status; it examines a patient’s perception of his physical and mental health in the context of day-to-day functioning. Though the self-assessment of patients with schizophrenia is often deemed to be unrealistic due to their reduced insight and criticism, it has been proven that the self-assessment of the measure of quality of life is more valid and reliable than the clinician’s assessment, particularly in non-acute phases of the disorder.39 The SF-36 questionnaire consists of 36 multiple choice questions that describe eight dimensions of the quality of life relating to health: physical functioning (ten questions), limitations relating to physical difficulties (four questions), limitations relating to emotional difficulties (three questions), social functioning (two questions), mental health (five questions), vitality and energy (four questions), physical pain (two questions), and perceptions of general health (five questions). The majority of questions pertain to the assessment of the patient’s condition over the past 4 weeks, to avoid the influence of the patient’s current mood. The final question in the questionnaire relates to the perceived change in health in comparison to the previous year. The answers to this question were not included in the statistical analysis. The possible range of results for each dimension is from 0 to 100. A lower result indicates reduced functioning or loss of function, reflecting that the patient’s health has declined. The validation of the questionnaire on various populations indicated the satisfactory psychometric characteristics.40–45 The Croatian version of the questionnaire was standardized and validated in 2006, and the instrument proved to be a valid and reliable measure of quality of life relating to health in the Croatian population.46 The initial testing in both groups of patients was conducted on the day of completion of the hospital treatment for each individual patient. This was repeated 6 months after the inclusion in the study and 6 months after the second testing, that is, 1 year after inclusion in the study. As an indicator of the level of patient functioning, data on the number of relapses and recidives were also collected, that is, the number of hospitalizations within and after 6 months from being housed in foster home care, or for the second group of patients, from their release from hospital treatment and return to the primary or secondary family.

The research was conducted as part of the project “Quality of life of psychiatric patients” that was conducted at the Sveti Ivan Psychiatric Hospital over a 5-year period.

Statistical methods

A statistical analysis of the data was conducted using the statistical program Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 11. To compare the groups on the individual dimensions of quality of life for the first, second, and third testing points, a t-test and analysis of variance were used. To determine whether there was a significant difference between the groups in certain dimensions of quality of life depending on the period of testing, that is, whether there was an interaction between the included types of treatment (foster home care and outpatient treatment) and the time points, a factorial analysis of variance was used (2×3 factorial design).

Results

The χ2 test and t-test showed no statistically significant differences between the groups of patients in terms of their sociodemographic characteristics: χ2 (sex) =0.002, P=0.965; t (age) =2.682, P=0.996; χ2 (educational level) =0.513, P=0.774; χ2 (marital status) =2.141, P=0.343.

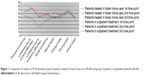

The average results on each dimension of quality of life of the SF-36 health questionnaire for both groups of patients at all three time points are shown in Table 3 and in Figure 1.

The factorial analysis of variance revealed statistically significant interactions between exposure to a certain type of treatment and the time point for the dimensions of physical functioning (F(2,276) =18.92, P<0.001), limitations due to emotional difficulties (F(2,276) =8.293, P<0.001), mental health (F(2,276) =6.733, P=0.001), and general health (F(2,276) =8.367, P<0.001). In the 1-year survey period, the patients treated in foster home care achieved significantly higher progress in these dimensions of quality of life than did the outpatients. There was also a significant main effect of time points for the dimensions of physical functioning (F(2,276) =5.321, P=0.005), limitations due to physical difficulties (F(2,276) =4.229, P=0.016), limitations due to emotional difficulties (F(2,276) =5.688, P<0.001), social functioning (F(2,276) =10.17, P<0.001), and energy/vitality (F(2,276) =4.159, P=0.017). Independent of the type of treatment, patients achieved better results at the second and third time points than at the first. The main effect of inclusion in a certain type of treatment, that is, foster home care or outpatient treatment, was not statistically significant for any dimension of quality of life except for mental health (F(1,276) =9.747, P=0.002): The patients in foster home care achieved better results on this dimension than the outpatients, regardless of the measurement time point.

Concerning the differences in the quality of life between the groups determined in each of the time points, Table 3 shows that at the first time point, patients treated in foster home care gave the poorest assessments of limitations due to emotional difficulties, whereas they had the fewest difficulties in physical pain. At the same time point, outpatients gave the poorest assessment to their energy/vitality and social functioning, though these results were not lower than 50, which is an average result on the scale. Meanwhile, they reported having the fewest difficulties in physical pain and physical functioning. Figure 1 shows that the outpatients had better results in all dimensions of quality of life at the first time point in comparison to patients in foster home care, with statistically significant differences observed in physical functioning (t=4.155, df =92, P<0.001), limitations due to physical difficulties (t=3.012, df =92, P=0.003), limitations due to emotional difficulties (t=3.581, df =92, P<0.001), physical pain (t=2.029, df =92, P=0.045), and overall health (t=2.453, df =92, P=0.016): Patients in foster home care achieved statistically significantly poorer results in these dimensions.

After 6 months, and a year after the inclusion of the patients in the study, the results of patients in foster home care showed a trend of improved functioning in all dimensions, with statistically significant changes observed in physical functioning (F(2,86) =14.845, P<0.001), limitations due to physical difficulties (F(2,86) =6.688, P=0.002), limitations due to emotional difficulties (F(2,86) =13.06, P<0.001), social functioning (F(2,86) =7.930, P=0.001), mental health (F(2,86) =3.542, P=0.030), and overall health (F(2,86) =4.588, P=0.012). A t-test showed significant differences between the first and the second measurement point in physical functioning (t=5.029, df =43, P<0.001), limitations due to physical difficulties (t=3.267, df =43, P=0.002), limitations due to emotional difficulties (t=4.143, df =43, P<0.001), social functioning (t=2.944, df =43, P=0.004), mental health (t=2.553, df =43, P=0.012), and overall health (t=2.751, df =43, P=0.007). The poorest functioning was in the area of energy/vitality, whereas the best functioning was in physical functioning. The trends of the results obtained at the second time point remained the same at the third time point, that is, 1 year after the initial inclusion of the patients in the study. No statistically significant differences were found in the results between these two measurement points. At the same time, a trend of poorer functioning was observed for the outpatients in the dimensions of physical functioning (F(2,98) =4.259, P=0.016), mental health (F(2,98) =3.676, P=0.028), physical pain (F(2,98) =4.518, P=0.013), and general health (F(2,98) =4.041, P=0.020), although no statistically significant differences were observed between the measurement points (t-test). The poorest result was in the dimension of mental and general health, whereas the best results were in limitations due to physical difficulties.

Figure 1 shows that the results of the patients in foster home care at the second and third time points were more similar to the results of outpatients than at the first time point, whereas some results were even higher for several dimensions. Statistically significant differences between the groups were obtained for the dimension of physical functioning (t=3.452, df =92, P<0.001), mental health (t=3.673, df =92, P<0.001), and overall health (t=2.487, df =92, P=0.015), with patients in foster home care achieving better results in these dimensions than outpatients.

With regard to the number of hospitalizations within the observed 1-year period, patients in foster home care had a total of five relapses and recidives, whereas outpatients had a total of eleven relapses and recidives.

Discussion

This study compared the self-assessments of patients treated in foster home care and patients in outpatient treatment on the different dimensions of health-related quality of life. Consistent with our expectations, the findings of this study showed that although, directly upon discharge from hospital, patients with schizophrenia who entered into housing and treatment in foster home care assessed their quality of life as poorer than did patients who returned to their families and entered into outpatient treatment, their assessed quality of life significantly improved over time. After 6 months of treatment out of the hospital, these patients even achieved better results in the dimensions of physical functioning, mental health, and overall health compared to patients in the outpatient program and also had fewer hospitalizations. These effects remained the same at the follow-up 1 year after the inclusion in the study.

These data are not in accordance with the assumption of a negative association of a restrictive environment and experiences of quality of life47 or with studies that showed no significant differences in the quality of life depending on the type of patient housing.26–29 However, the findings correspond to those of Leiße and Kallert,30 who found that patients in various nonhospital institutions expressed significantly higher satisfaction with their life than patients who lived alone or with their families. Therefore, in the observed year, patients treated in foster home care showed significantly higher progress in the context of their quality of life, as observed in the statistically significant interaction between the type of treatment and the time points of testing on the dimensions of physical functioning, limitations due to emotional difficulties, mental health, and general health. However, caution is necessary when comparing the findings with other studies. In particular, the heterogeneity of the methods applied in different studies limits the generalization and comparability of the findings.

The changes obtained could possibly be attributed to the characteristics of the housing and treatment in foster home care. Due to the nature of this study, it is difficult to determine which specific aspect of the services offered to the patients (group psychodynamic psychotherapy, family therapy, work and occupational therapy) contributed the most to these findings. We presume that this is the effect of sociotherapy as a whole, that is, as a result of socialization in the local community and in the families where there are no conflicts and maladaptive models of communication. A new environment, in addition to objectively better living conditions, offers a wider social network, and a wider social network and social support are significantly associated with a positive subjective assessment of quality of life.48 Furthermore, patients in foster home care are surrounded by individuals with similar difficulties, and they have the opportunity to participate in various socio-recreational activities. Educated foster families, with the assistance of the expert hospital team, are able to provide patients with continuous care, compassion, support, and supervision. Patients’ self-worth and self-esteem increase, and the prejudices between the patients and the society gradually disappear.35

On the contrary, patients who return to their own families often return to an environment that does not accept them and considers them as less valuable, dangerous, and useless.35 In addition, schizophrenia can cause disabling experiences and distress to both people with schizophrenia and their families, and caring for patients is often described as burdensome, which can have a negative effect on a patient’s illness.11

As stated before, on the day of completing the hospital treatment, outpatients gave higher assessments of their quality of life than did patients in foster home care treatment. Statistically significant differences were found between the groups in the dimensions of physical functioning, limitations due to physical difficulties, limitations due to emotional difficulties, physical pain, and overall health. Independent of the similarities of the observed groups in terms of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, there were differences between them that could not be controlled, and therefore, it is likely that the patients selected for treatment in foster home care assessed their quality of life as poorer. In particular, patients who are placed in foster home care do not have the ability to live independently, and they have poor life opportunities and insufficient social support, all of which significantly affect their quality of life. On the contrary, patients treated in outpatient conditions have better living conditions and the support and understanding of their families, which might also be reflected in the greater care for their own health and account for the somatic differences obtained between the groups.

After 6 months and 1 year after being included in the study, the patients treated in foster home care assessed their quality of life as better in all dimensions in comparison with the results of the first survey time point, with statistically significant differences obtained in the area of physical functioning, limitations due to physical difficulties, limitations due to emotional difficulties, social functioning, mental health, and overall health. In that way, their results approached the results of the outpatient group at the first survey time, whereas the results of the outpatient group did not change significantly in comparison to the first survey time point. In many dimensions, there was even a trend that the quality of life was assessed as poorer. There were no statistically significant differences between the second and the third measurement points indicating the stability of the results for at least 1 year upon the inclusion of the patients in the study. The results obtained for patients in foster home care are in line with the findings of earlier studies on the improvement of quality of life after discharge from hospital.24,25 However, the results obtained for the outpatient group did not corroborate these findings. It is possible that they did not achieve an improvement in the quality of life due to their return to their old environment and the need to again face old problems. Furthermore, the quality of life of primary and secondary families of patients with schizophrenia is often significantly disturbed, and these families are very often dysfunctional.35

As an additional indicator of health and quality of life of patients, the number of hospitalizations for the groups during the study period was compared. In this 1-year period, there were twice as many hospitalizations for the outpatient group than for the group in foster home care. One possible reason for this is the fact that patients in foster home care are regularly visited by the expert team, who, along with the trained foster families, closely monitor their mental state, intervene where necessary, and modify pharmacotherapy as needed.

It is necessary to stress several important limitations of the study. The sample of patients was relatively small, which is a possible reason for the high variability of the obtained results. Furthermore, the sample is specific in its sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, as are the foster families and the primary or secondary families of patients treated in the outpatient program. Patients were not randomized into groups because the assessment was conducted in real conditions. Furthermore, the group of patients treated in the outpatient program was selected so that they corresponded in terms of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics to the group of patients treated in foster home care to control the influence of those characteristics on the results. In that way, this group was, in fact, highly selected and therefore does not represent the general population of outpatients with schizophrenia. These factors combined make it difficult to generalize the results, and therefore, further research is necessary to more reliably conclude on any possible effects of this type of housing, treatment, and rehabilitation on the wide population of psychiatric patients.

Furthermore, the obtained significant progress in certain dimensions of quality of life cannot exclusively be attributed to the type of treatment, that is, the environment in which the patient is placed after hospitalization. Other factors that could not have been controlled might also have had significant effects, such as possible differences between groups in emotional conditions, personality characteristics, level of work and social functioning, and insight and criticism of the patients. Different studies have shown positive associations between quality of life and self-esteem,49,50 premorbid social adaptation,36 social support,50–53 personality traits such as extraversion and agreeableness,54 low levels of harm avoidance, novelty seeking, and self-directedness.50 Moreover, no research-based instrument was used to measure the type and/or intensity of psychopathological symptoms, although it is known that quality of life is significantly associated with the quantity and intensity of the expression of the psychopathological symptoms.55–57 It is also possible that the patients housed in foster home care have lower expectations and more realistic goals than the outpatient group, and the individuals with which they compare themselves are also patients, that is, persons with similar mental disturbances and similar living situations, which ultimately could influence the higher satisfaction of quality of life in comparison with those in outpatient treatment.30 The expectations of patients with schizophrenia have indeed proven to be significant predictors of their quality of life.58

Additionally, self-assessment is always prone to subjectivity and is poorly associated with the objective indicators of quality of life, and it is significantly associated with the current mood.3 Therefore, it would be beneficial to also use other sources of information, such as assessments on the patient’s quality of life by a family member. Future research should consider these shortcomings, and it would be interesting to study which aspects of housing and treatment in foster home care are significantly associated with patients’ experiences of quality of life, for example, staying with the family, the quality of interpersonal relations, social support, the fact that other psychiatric patients are also housed within the foster family, the education of family members on the patient disorders, and the certain types of activities implemented within the housing, treatment, and rehabilitation of patients. Additionally, in this study, a relatively narrow construct was tested, that is, health-related quality of life. It would be interesting to test the quality of life in a broader sense, including the social, environmental, and material factors, considering that satisfaction in one aspect of life does not automatically imply satisfaction in all other areas of life.

Acknowledgment

This study has been conducted as a part of the scientific project “Quality of life of psychiatric patients”, Ministry of Science, Education and Sport, Republic of Croatia (project number: 278-0000000-071, project coordinator: Mate Mihanović, PhD).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interests in this work.

References

Lambert M, Naber D. Current issues in schizophrenia: overview of patient acceptability, functioning capacity and quality of life. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(suppl 2):5–17. | ||

Sartorius N. The meanings of health and its promotion. Croat Med J. 2006;47(4):662–664. | ||

Priebe S. Social outcomes in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;191(50):15–20. | ||

Lehman AF. Instruments for measuring quality of life in mental illnesses. In: Katschnig H, Freeman H, Sartorius N, editors. Quality of Life in Mental Disorders. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1997:79–94. | ||

Burns T. Evolution of outcome measures in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;191(suppl 50):1–6. | ||

Chien WT, Yip AL. Current approaches to treatments for schizophrenia spectrum disorders, part I: an overview and medical treatments. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:1311–1332. | ||

Juckel G. Postpsychotische depression. Psychoneuro. 2005;31:426–432. | ||

Becker M, Diamond R. New developments in quality of life measurement in schizophrenia. In: Katschnig H, Freeman H, Sartorius N, editors. Quality of Life in Mental Disorders. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1997:119–133. | ||

Boyer L, Millier A, Perthame E, Aballea S, Auquier P, Toumi M. Quality of life is predictive of relapse in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:15. | ||

Kao Y, Liu Y, Cheng T, Chou M. Subjective quality of life and suicidal behavior among Taiwanese schizophrenia patients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:523–532. | ||

Chien WT, Leung SF, Yeung FK, Wong WK. Current approaches to treatments for schizophrenia spectrum disorders, part II: psychosocial interventions and patient-focused perspectives in psychiatric care. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:1463–1481. | ||

Laklija M, Barišec A. Iskustvo udomiteljstva odraslih osoba s duševnim smetnjama iz perspektive udomitelja (Experience of foster care for adults with mental disabilities from the perspective of foster family members). Soc psihijat. 2014;42:50–61. | ||

Mubarak AR, Baba I, Chin LH, Hoe SQ. Quality of life of community-based chronic schizophrenia patients in Pengang, Malaysia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2003;37:577–585. | ||

Gaite L, Vazquez-Barquero JL, Borra C, et al; EPSILON Study Group. Quality of life in patients with schizophrenia in five European countries: the EPSILON study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;105:283–392. | ||

Bechdolf A, Klosterkötter J, Hambrecht M, et al. Determinants of subjective quality of life in post acute patients with schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;253:228–235. | ||

de Souza LA, Coutinho ES. The quality of life of people with schizophrenia living in community in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(5):347–356. | ||

Evans S, Banerjee S, Leese M, Huxley P. The impact of mental illness on quality of life: a comparison of severe mental illness, common mental disorder and healthy population samples. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:17–29. | ||

Simpson CJ, Hyce CE, Faragher EB. The chronically mentally ill in community facilities: a study of quality of life. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:77–82. | ||

Warner R, Huxley P. Psychopathology and quality of life among mentally ill patients in the community British and US samples compared. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;163:505–509. | ||

Browne S, Roe M, Lane A, et al. Quality of life in schizophrenia: relationship to sociodemographic factors, symptomatology and tardive dyskinesia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;94:118–124. | ||

Sellwood W, Thomas CS, Tarrier N, et al. A randomised controlled trial of home-based rehabilitation versus outpatient-based rehabilitation for patients suffering from chronic schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:250–253. | ||

Anderson RL, Lewis DA. Quality of life of persons with severe mental illness living in an intermediate care facility. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56(4):575–581. | ||

Kasckow JW, Twamley E, Mulchahey JJ, et al. Health-related quality of well-being in chronically hospitalized patients with schizophrenia: comparison with matched outpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2001;103(1):69–78. | ||

Barry MM, Crosby C. Assessing the impact of community placement on quality of life. In: Crosby C, Barry MM, editors. Community Care: Evaluation of the Provision of Mental Health Services. Aldershot Hants: Averbury; 1995:137–168. | ||

Barry MM, Zissi A. Quality of life as outcome in evaluating mental health services: a review of the empirical evidence. Soc Psychiat Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1997;32:38–47. | ||

Nilsson L, Levander S. Quality of life and schizophrenia: no subjective differences among four living conditions. Nord J Psychiatry. 1998;52(4):277–283. | ||

Jarema M, Bury L, Konieczyńska Z, et al. Comparison of quality of life of schizophrenic patients in different forms of psychiatric care. Psychiatria Pol. 1998;32:107–115. | ||

Grawe RW, Lovaas AL. Quality of life among schizophrenic in- and out-patients. Nord J Psychiatry. 1994;48(3):147–151. | ||

Yeung FK, Chan SH. Clinical characteristics and objective living conditions in relation to quality of life among community-based individuals of schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Qual Life Res. 2006;15(9):1459–1469. | ||

Leiße M, Kallert TW. Social integration and the quality of life of schizophrenic patients in different types of complementary care. Eur Psychiatry. 2000;15:450–460. | ||

Chan GW, Ungvari GS, Shek DT, Leung JJ. Hospital and community-based care for patients with chronic schizophrenia in Hong Kong – quality of life and its correlates. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38:196–203. | ||

Vuletić G. Generacijski i transgeneracijski čimbenici kvalitete života vezane za zdravlje studentske populacije (Generational and trans-generational factors of quality of life related to the health of the student population), PhD Thesis, University of Zagreb School of Medicine, Zagreb, 2004. | ||

Linn MW, Klett CJ, Caffey EM. Foster home characteristics and psychiatric patient outcome. The wisdom of Gheel confirmed. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37(2):129–132. | ||

Milošak A. Liječenje u tuđim obiteljima kao jedna od metoda resocijaliziranja psihijatrijskih bolesnika (Treatment in foster families as one of the methods of resocialization of the psychiatric patients). Soc psihijat. 1973;2–3:205–218. | ||

Milošak A, Bašić M. Prolonged hospital treatment of patients in families other than their own. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1981;27(2):129–133. | ||

Milošak A, Ljubin N. Utjecaj smještavanja shizofrenih bolesnika u tuđe obitelji na simptomatologiju shizofrene psihoze (The impact of foster home care treatment on psychopathological symptoms of patients with schizophrenia). Soc psihijat. 1975;3:235. | ||

World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. Geneva: WHO; 1992. [Tenth Revision]. | ||

Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36® Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA: New England Medical Center, The Health Institute; 1993. | ||

Becchi A, Rucci P, Placentino A, Neri G, de Girolamo G. Quality of life in patients with schizophrenia – comparison of self report and proxy assessments. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:397–401. | ||

McHorney CA, Ware JE, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36 item short form health survey (SF 36): tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40–66. | ||

Ware JE Jr, Gandek B, Kosinski M, et al. The equivalence of SF-36 summary health scores estimated using standard and country-specific algorithms in 10 countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1167–1170. | ||

Sanson-Fisher RW, Perkins JJ. Adaptation and validation of the SF-36 health survey for use in Australia. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:961–967. | ||

Kagee A. Review of the SF-36 health survey. In: Plake BS, Impara JC, editors. The Fourteenth Mental Measurements Yearbook. Lincoln, NE: Buros Institute of Mental Measurements; 2001:183–190. | ||

Pukrop R, Schlaak V, Möller-Leimkühler AM, et al. Reliability and validity of quality of life assessed by the short form 36 and the modular system for quality of life in patients with schizophrenia and patients with depression. Psychiatry Res. 2003;119:63–79. | ||

Zhang Y, Qu B, Lun S, Guo Y, Liu J. The 36-item short form health survey: reliability and validity in Chinese medical students. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9:521–526. | ||

Maslić Seršić D, Vuletić G. Psychometric evaluation and establishing norms of Croatian SF-36 health survey: framework for subjective health research. Croat Med J. 2006;47:95–102. | ||

Bobes J, Gonzalez MP. Quality of life in schizophrenia. In: Katschnig H, Freeman H, Sartorius N, editors. Quality of Life in Mental Disorders. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1997:165–178. | ||

Cechnicki A, Wojciechowska A, Valdez M. The social network and the quality of life of people suffering from schizophrenia seven years after the first hospitalisation. Arch Psychiatr Psychother. 2008;2:31–38. | ||

Hansson L, Middelboe T, Merinder L, et al. Predictors of subjective quality of life in schizophrenic patients living in the community. A Nordic multicentre study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1999;45:247–258. | ||

Ritsner M. Predicting changes in domain-specific quality of life of schizophrenia patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191:287–294. | ||

Fitzgerald PB, Williams CL, Corteling N. Subject and observer-rated quality of life in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103:387–392. | ||

Eklund M, Backstrom M, Hansson L. Personality and self-variables: important detenninants of subjective quality of life in schizophrenia out-patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;108:134–143. | ||

Eack S, Newhill CE, Anderson CM, Rotondi AJ. Quality of life for persons living with schizophrenia: more than just symptoms. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2007;30(3):219–222. | ||

Kentros MK, Terkelsen K, Hull J, Smith TE, Goodman M. The relationship between personality and quality of life in persons with schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia. Qual Life Res. 1997;6:118–122. | ||

Addington J, Young J, Addington D. Social outcome in early psychosis. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1119–1124. | ||

Hofer A, Rettenbacher M, Widschwendter C, Kemmler G, Hummer M, Fleischhacker WW. Correlates of subjective and functional outcomes in outpatient clinic attendees with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:246–255. | ||

Gorna K, Jaracz K, Rybakowski F, Rybakowski J. Determinants of objective and subjective quality of life in first-time-admission schizophrenic patients in Poland: a longitudinal study. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:237–247. | ||

Wilson-d’Almeida K, Karrow A, Bralet MC, Bazin N, Hardy-Bayle MC, Falissard B. In patients with schizophrenia, symptoms improvement can be uncorrelated with quality of life improvement. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28(3):185–189. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.