Back to Journals » Journal of Pain Research » Volume 12

Qualitative evaluation of an interdisciplinary chronic pain intervention: outcomes and barriers and facilitators to ongoing pain management

Received 29 August 2018

Accepted for publication 23 January 2019

Published 1 March 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 865—878

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S185652

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Katherine Hanlon

Lauren S Penney,1,2 Elizabeth Haro1,2

1South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA; 2Department of Medicine, The University of Texas Health at San Antonio, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA

Background: Many leaders in the field of chronic pain treatment consider interdisciplinary pain management programs to be the most effective treatments available for chronic pain. As programs are instituted and expanded to address demands for nonpharmacological chronic pain interventions, we need to better understand how patients experience program impacts, as well as the challenges and supports patients encounter in trying to maintain and build on intervention gains.

Methods: We conducted a qualitative evaluation of an interdisciplinary chronic pain coaching program at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs. A purposive sample of Veterans were engaged in interviews (n=41) and focus groups (n=20) to elicit patient outcomes and barriers and facilitators to sustainment of improvements. Transcripts were analyzed using matrix and thematic analyses.

Results: Veterans reported various outcomes. Most frequently they described adopting new self-care or lifestyle practices for pain management and health. They also often described accepting pain, being better able to adjust and set boundaries, feeling more in control, participating in life, and changing their medication use. A small portion of the sample reported no improvement in their conditions. When outcomes were examined as a whole, individuals described impacts that could be placed along a spectrum from whole life change to no change. Facilitators to maintenance of improvements included having building blocks (eg, carrying forward practices learned), support (eg, access to resources), and energy (eg, motivation), and improving incrementally. Challenges were not having building blocks (eg, life disruptions), support (eg, unknown follow-up options), and energy (eg, competing demands) and having an unbalanced rate of improvement.

Conclusion: Most Veterans identified experiencing multiple areas of improvement, especially learning about and taking up new pain and general health management skills. Ensuring participants can build on and find support for these outcomes when applying what they have learned in their dynamic social and physical worlds remains a challenge for this program and other relatively short-term interdisciplinary chronic pain interventions.

Keywords: chronic pain, multimodal treatment, interviews, quality improvement

Background

There is broad recognition that the predominant mode of treating chronic pain with pharmaceuticals has not been effective as hoped and had unintended consequences.1–3 As our health care systems shift from promoting biomedical models of chronic pain to biopsychosocial models, interdisciplinary and multidimensional treatment interventions for chronic pain are being encouraged.4,5 These interventions focus less on bringing patient’s pain levels to zero and more on patient’s active self-management to reduce and cope with pain.

Interdisciplinary pain programs that incorporate multimodal approaches have been shown to be effective for improving chronic pain management.6–10 Although components and delivery of interdisciplinary pain management programs vary, making it challenging to compare effectiveness,11 they often include staff from disciplines that can address complementary aspects of the biopsychosocial model of pain. These staff include physicians, clinical psychologists, physical therapists, and other healthcare professionals as needed.5 Treatments mostly include medicine, psychotherapy, physiotherapy, and/or relaxation techniques.12

Studies demonstrate that such programs generally yield positive physical and psychosocial outcomes in patients.6,7,12–18 Physical improvements have been observed in disability, functional status, self-care, and fitness.6,15,17,19 Positive psychosocial outcomes include improvements in depressive symptoms, pain anxiety, and readiness to change.14,15,17 Some studies have also observed decreases in use of pain medications, including opioids.13,20

However, authors have highlighted inconsistencies in outcomes across studies,21 chronic pain subgroups,12 participants’ age and gender,22 and patients within studies.15–17 Within studies, not all participants in programs experience the same degree or direction of change15,16 and some may experience losses of gains over time.19 Day et al15 found that across most of their psychosocial, social, and physical outcome measures, about half of the participants in their group interdisciplinary pain intervention experienced clinically significant positive change, around 40% experienced no significant change, and in less than 10% the condition deteriorated. Donath et al identified that 58% of their multimodal program participants experienced at least a half SD improvement in four of the five constructs (pain severity, disability due to pain, depressiveness, and physical- and mental health-related quality of life).23

The few qualitative studies conducted on these programs have found that participants may perceive changes in the ways they engage in life and personal growth, but experience varying challenges to sustaining change. In the study by Bremander et al,24 participants described their partially inpatient intervention as a process of “changing one’s life plan”, but varied in terms of the degree to which their lives were changed. Six months after the intervention, those who made life adjustments rather than whole life changes were more likely than others to stagnate in their life management. In the mixed-methods study by Wideman et al,25 participants described personal growth (ie, acceptance, resilience, and capacity; motivation to engage in meaningful activity; and self-worth), factors that impacted personal growth, and ongoing challenges (eg, to pain acceptance, maintaining skills and strategies). Importantly, participants’ perceptions of improvements were not captured in quantitative measures.

As we expand the reach of interdisciplinary chronic pain programs, understanding differences in outcomes, patients’ perceptions of program outcomes, and the challenges and supports that the patients experience in trying to sustain and build on positive outcomes will be important to take efforts to implement more effective pain programming. While published research on the impacts of interdisciplinary pain programs is established using various standardized measures, there is little information about the barriers and facilitators to self-management after leaving such programs (for exceptions, see Ref. 26). The primary objective of this project was to describe Veterans’ perceived impacts of participation in an interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation program. The second aim was to identify after-program pain management barriers and facilitators experienced by program participants. By sharing the experiences of Veterans who use the program, we illustrate participants’ perceptions of their successes and challenges following program participation to directly inform ongoing quality improvement efforts and apprise others who may be engaged in similar chronic pain programmatic efforts.

Methods

Setting

Data described in this manuscript were collected for an evaluation that we conducted of the Empower Veterans Program (EVP) at the Atlanta Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System as part of ongoing quality improvement work. The site is one of the more than 1,700 facilities that comprise the Veterans Health Administration, the largest integrated health care system in the United States. The organization provides primary, specialized, and institutional-based care and supportive services to more than nine million military veterans.27 To qualify for health benefits, veterans must have served in active duty and not been dishonorably separated from military service.

EVP is a 10-week, 30+ hour whole health group training program for self-care for chronic pain. Any Veteran within the Atlanta VA system with chronic pain can self-refer or be referred to enroll in EVP. There is no limit on the number of times Veterans can participate. Veterans attend weekly 3-hour classes with a cohort of 8–12 peers and engage in one-on-one coaching with interdisciplinary team members. All classes take place in a large conference room in a community-based outpatient clinic in a suburban community outside of Atlanta. Individual coaching takes place by phone as well as in person as deemed appropriate. The interdisciplinary team includes chaplains, clinical psychologists, physical therapists, social workers, clerks, and medical doctor/director. EVP curriculum is composed of three parts as follows: whole health (mindfulness activities and exploration of issues that might impact pain, such as nutrition and relationships); Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; discussion of personal values and how thoughts, feelings, and behaviors relate to pain); and mindful movement (development of body awareness and safety in movement).

Our evaluation utilized qualitative methods to understand program processes and impacts from the perspective of EVP participants. Veterans were engaged in interviews and focus groups between October 2016 and August 2017. Data collection was completed by the authors, a PhD medical anthropologist (LP) and an experienced research assistant with an MPH (EH). Neither had prior relationships with any of the study participants.

Participants

We employed slightly different sampling strategies for interviews and focus groups. Sampling targets were guided by a desire to collect a diverse range of experiences, resources available to the Quality Improvement (QI) team, and research related to non-probabilistic sampling to thematic saturation.28,29 Potential Veteran participants for interviews were identified using EVP referral and enrollment lists (for May 2015–December 2016), EVP staff recommendations, and volunteers from pilot focus groups. From this cohort (760 Veterans, 488 who had enrolled in EVP and 272 who were referred to but never enrolled in EVP), to ensure sample diversity, we created a stratified purposeful sample by categorizing all potential participants into nonoverlapping groups by program status (graduate, noncompleter [defined as attending fewer than 8 of 10 group classes], and never attended [defined as referred to the program but never attended a class]). Graduates were further stratified into men, women, and people with previous EVP noncompletion. Noncompleters were further stratified by persons having multiple noncompletions, attendance in all women’s group, or attendance in mixed-gender groups. Purposeful random selection of participants within each stratum was then carried out; we aimed to recruit 24 graduates, 8 noncompleters, and 8 who never attended.

Eligible participants were recruited via telephone by LP or EH to participate in semi-structured interviews about their experience with EVP. Persons who declined to participate or who were unsuccessfully contacted after three attempts were removed and replaced with a new potential participant. Because of difficulties encountered recruiting Veterans who had never attended EVP (mostly because we could not reach them), we over recruited for the other two groups.

To collect data from Veterans who had more recently gone through EVP, we identified a purposive random sample of Veterans who were enrolled in EVP between December 2016 and August 2017 (138 Veterans) to participate in focus groups. They were identified using an internally kept EVP attendance log provided by EVP staff. We excluded any Veteran on this list who participated in an interview. Veterans were invited to participate in one of six focus groups. Focus groups were stratified by gender (male, female). We aimed for six participants per focus group. Eligible veterans were recruited by EH by phone. Recruitment included a detailed description of the goals of the study and focus groups. Persons who declined or who had unsuccessfully contacted after three attempts were removed and replaced from our potential sample list with a new participant.

The Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) Research Office determined that EVP’s quality improvement work was not research. All potential participants were informed of the purpose and intended use of the data collected, assured confidentiality, and informed that they could decline to answer any question they were asked or cease participation at any point without penalty. Participants were asked to give oral rather than written consent before engaging in interviews or focus groups so as to limit the risk of breach of confidentiality.

Data collection

Veteran interviews were conducted over the phone by the authors from January 2017 to July 2017. We developed and iteratively refined a semi-structured interview guide (Supplementary material 1). Veteran focus groups were conducted in-person in August 2017. Focus groups were carried out by the authors using a semi-structured focus group guide (Supplementary material 2) adapted from a mind-mapping exercise used by Burgess-Allen and Owen-Smith.30 Although interviews were designed to collect detailed information about individual Veteran’s experiences inside and outside the program, focus groups were targeted to highlight diversity in perspectives and to allow group members to provide affirmations and checks on each other’s responses.31 Both interview and focus group guides contained open-ended questions concerning program outcomes and prompts to elicit information about postprogram barriers and facilitators to pain management.

Detailed interview and focus group notes were taken during data collection. When participants consented to audio recording, interviews and focus groups were also recorded and later professionally transcribed.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using deductive (predefined domains) and inductive (patterns within domains) approaches. Transcripts were analyzed using a matrix approach in Excel spreadsheets.32 Data were inputted into the matrices by domains of interest (eg, Veteran outcomes, facilitators post-EVP, and challenges post-EVP) by both authors. Domains stemmed from evaluation objectives and the interview and focus group guide questions. For example, the Veteran outcomes domain was created based on the aim to describe participants’ perceptions of program impacts and corresponded with the interview question: “Since enrolling in EVP, what if anything are you doing differently to manage your pain?” and focus group questions: “Thinking about your time since you’ve gotten out of EVP, what do you think has gone really well in terms of your pain management? What has been challenging?” Participants’ responses to questions did not always map entirely onto the domain(s) associated with those questions. For example, when discussing changes in pain management practices, interviewees might also discuss challenges in maintaining new practices that would fit under the challenges post-EVP domain. Thus, the authors had to interpret and sort responses into their proper domains. Reliability was assured by the pair independently summarizing the domain material for 15% of the participants and reaching a shared understanding of the material to be included in each domain. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by agreeing upon content for each matrix domain summary. Focus group data were coded in NVivo qualitative analysis software33 by LP after interview analysis was completed. Focus group transcripts were also initially coded broadly by domains of interest (eg, outcomes, post-EVP gone well, and post-EVP challenges).29

The authors inductively identified patterns or themes within each broad domain. Themes were developed to express latent meanings and participants’ lived experiences.34 Themes were constructed by cutting and sorting similar responses into clusters and then developing the theme based on abstraction of meaning in each cluster.35 Themes were compared through triangulation between conceptually related domains for interviews and focus groups.

Results

We recruited 41 Veterans to participate in interviews. Of the 98 Veterans invited to participate in interviews, 36 (37%) could not be reached, 14 (14%) declined participation, and 7 (7%) agreed but could not be reached on the day of the interview. Of those who participated in interviews, 31 (76%) had completed EVP, 7 (17%) did not complete EVP, and 3 (7%) never attended the program.

Twenty Veterans participated in focus groups. Of the 97 veterans contacted to participate in focus groups, 25 (26%) could not be reached, 38 (39%) declined participation, and 14 (14%) agreed but did not attend the focus group. Focus group size ranged from 1 to 5 Veterans, with an average size of three participants. Thirteen (65%) focus group participants were female. Of those who participated, 18 (90%) had completed the program and 2 (10%) had not.

Demographics of participants in comparison to demographics of all EVP enrollees are presented in Table 1. Mean age of the participants in our sample was 53 years and 51% were female. Seventy percentage of the participants were identified as Black/African American, 15% White, 2% bi/multiracial, and 13% were of unknown racial background. Interviews lasted an average of 26 minutes and ranged from 6 to 81 minutes in length. Focus groups were an average of 59 minutes and ranged from 24 to 86 minutes.

Veteran-reported outcomes

Veterans described various outcomes, from adoption of concrete coping skills to feelings of empowerment and positivity (see Table 2 for a full list of major categories of change and illustrative quotes). There were no identified differences in outcomes reported by different subsamples. The most frequently described changes were new self-care or lifestyle practices to help manage pain and health. These practices included exercise, meditation, eating healthier, and general coping skills (eg, resting when needed).

| Table 2 Veteran-reported outcomes (based on interview and focus group data) Note: Data in parenthesis represents the participant identifier. Abbreviation: EVP, Empower Veterans Program. |

Veterans also often described learning to accept their pain. With that understanding came a commitment to adjusting their lifestyle (eg, using a wheelchair when needed) and practices (eg, splitting tasks down into incremental stages) to accomplish things that mattered to them. A handful of Veterans expressed awareness that this required finding boundaries and a balance between 1) pushing too hard which might exacerbate pain and 2) resting or avoiding pain too much which risked disengagement. As Veterans described these changes, about a quarter specifically mentioned feeling more in control since leaving EVP. For some, this sense of empowerment went beyond their relationship with chronic pain, to the ways they interacted with their providers, family, and friends, and to their life more generally. Some of those describing such shifts also described major whole life changes and a different, more engaged way of being in the world.

Some Veterans also said that since leaving EVP they had altered and reduced the way they used pain medication to manage their pain. Examples of changed usage included being more mindful of and deliberative about when they took their medications, rather than taking them whenever they felt pain or at their usual time.

Finally, a small group of Veterans described no improvement since participating in EVP. They described being stuck in the same place and of thinking about pain in the same way. With this came a sense of resignation and/or frustration.

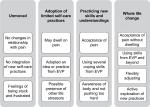

Because we had richer, individual data from Veterans who participated in interviews, in addition to looking at individual changes Veterans described and how those fit into broader categories, we looked at the total changes each Veteran experienced. We noticed an apparent continuum of change (Figure 1).

| Figure 1 Continuum of change as told by Veterans in interviews. Abbreviation: EVP, Empower Veterans Program. |

On one end were a minority of Veterans who experienced no change. These Veterans described feelings of frustration since leaving EVP. In the middle were most Veterans, who described adopting some of the practices and skills they learned in EVP and, to some degree, accepting pain. Veterans in those categories described implementing a single or limited idea or practice from the program (eg, do morning stretches learning EVP, accept pain), whereas others talked about drawing on multiple components or understandings from EVP (eg, eat healthier, employ coping skills when in pain, and make time to connect with friends). These Veterans varied in terms of the challenges they described to adopting more life changes (eg, family stressors and continued ill health) and their general understandings of the program (eg, limited demonstrated understanding of EVP components to broader grasp of the three major pieces of curricula). On the other end of the spectrum were a minority of Veterans who left EVP eager to learn more, who took comprehensive understandings of the EVP components and applied them to many aspects of their lives to experience whole life changes. Illustrative quotes and discussions are presented in Table 3.

| Table 3 Examples of Veteran-reported outcomes by continuum category Abbreviations: EVP, Empower Veterans Program; VA, Veterans Affairs. |

Post-EVP facilitators and barriers

Interviewees and focus group participants described facilitators and barriers that mirrored each other. We separated them into four broad themes as follows: building blocks, support, energy, and trajectory (Table 4).

Veterans frequently described how the presence or absence of essential building blocks either supported or challenged their pain management after EVP. Veterans talked about using strategies and approaches they had started practicing in EVP (eg, doing stretches from EVP every morning), drawing on course handouts and materials (eg, mindfulness CDs), and creating their own daily routines that buttressed their self-care. At the same time, some discussed that life disruptions to their routines, forgetting EVP teachings, and leaving EVP without a firm understanding of coping skills made self-management difficult.

The existence or lack of support also reportedly impacted Veterans’ success. Positive supports included having access to resources such as EVP’s weekly movement class for graduates, discounted gym memberships and recreation classes, and Buprenorphine; opportunities for reinforcement, such as through formal standalone ACT programs or continued physical therapy; and additional social support, such as through an activity partner or supportive and understanding partner. Similarly, Veterans discussed how lacking access to continued services (eg, because of distance or cost involved), not knowing what services are available, and lacking social support made trying to implement what they had learned in EVP more challenging.

Having a motive force in the form of aims or positive perspective was described as facilitating adoption of coping skills and self-care practices. Veterans noted how momentum from EVP graduation and having specific goals (eg, traveling to see a grandchild) and responsibilities (eg, caring for a dog) helped keep them motivated to continue practices learned in EVP. Some also mentioned how optimism could help them not get stuck on the experience of pain. However, competing responsibilities (eg, work), life stressors (eg, death of a spouse, homelessness), and depression were all described as hampering self-care efforts.

Finally, Veterans who described incremental progress seemed to have more successful post-EVP experiences. These Veterans talked about working to balance challenging themselves with taking care of their needs, in a way that kept moving them forward. However, Veterans who characterized their experiences as less balanced, either swinging from highs and lows or feeling stuck in one place, seemed to find pain management more challenging.

Discussion

Our evaluation found that most Veterans described positive outcomes from their participation in EVP. Degree and type of outcome varied, but included adopting new self-care practices, acquiring coping skills, accepting pain, feeling more in control, participating in life, adjusting to pain and finding more balance, and changing medication use. However, some said that they did not perceive improvement. Participants described multiple conditions and factors that either supported or challenged their ability to maintain positive gains after leaving EVP.

Veterans who participated in interviews could be categorized into qualitatively different subgroups based on their perceived outcomes. On one end of the spectrum were a group of people who described EVP as instigating whole life change. On the other end, were Veterans who told of no change. These were similar to Bremander et al’s24 categories of “overall life changes” and “stagnation”. In this project, we were unable to identify a priori, demographic factors that might help to explain this heterogeneity. Several studies of interdisciplinary pain interventions have examined patient predictors for standardized outcomes. Day et al15 found that higher baseline depression scores, having nociceptive pain, and being older were predictive of increased improvement, whereas Donath et al23 found that pain severity, disability due to pain, and number of pain-related physician visits in the past 6 months were predictive of classification as program success (notably, depressiveness was not predictive in the study by Donath et al). Additional work is needed to understand when and what patient-level factors might interact with intervention characteristics to impact outcomes. Such patient-level factors might include comorbidities, type and severity of chronic pain, readiness for change, previous treatment experiences, pain-related treatment usage, and/or the degree to which interventions align with patient understandings of their conditions and goals. Intervention-level characteristics should also be investigated, these might include documentation setting, structure, curriculum, patient centeredness, disciplines involved, degree of interdisciplinarity, and coordination with outside pain providers. By understanding such factors, we might better support individuals for program success by, for example, preparing them for treatment (eg, motivational interviewing, expectation setting) or better matching patients and interventions.

Notably, most Veterans acknowledged that the pain continued in their life. Few spontaneously mentioned any improvement in pain since participating in EVP. Especially if their pain medications had been tapered, some described increased pain. However, most endorsed that they were at least aware that pain would be chronic and had skills and tools to help them manage pain in a way that fit their lives and helped them feel more in control. In addition, the sense of empowerment and engagement in life that participants reported suggest that Veterans derived benefits from the program beyond pain management. This is similar to the findings of the mixed-methods study by Wideman et al,25 which found that patients reported limited improvement in standardized, clinical measures, but did report meaningful and enduring personal growth. Future studies may want to incorporate a broader array of mixed methods for assessing impacts.

The challenges and supports participants experienced post-EVP are similar to those identified in Bair et al’s study of barriers and facilitators to pain management strategies after an interdisciplinary intervention26 and in studies of barriers and facilitators to nonpharmacological pain treatment.36–40 Veterans in our study echoed many of the same barriers that Veterans reported to Bair et al almost a decade ago. These included lack of social support, resource barriers to accessing or doing different strategies, depression, and other life stressors or priorities.26 Also in the VA, Becker et al’ participants described access to care, patient and provider awareness or knowledge and treatment beliefs, patient–provider interaction, and patient social support and provider health care system support as top facilitators and barriers to nonpharmacological therapy.37,38 Veterans we talked to reflected similar experiences in terms of support (eg, having or not having access to resources, not knowing about other pain management options, having or not having social support) and energy (eg, motivation, positive outlooks) for chronic pain management post-EVP. Patient and provider beliefs about nonpharmacological treatments probably also played a role in the participants in our study, with Veterans and providers more open to such therapies more likely to, respectively, participate in or to refer patients to EVP. While addressing patient and provider preferences and beliefs about multimodal pain therapies, and distrust that might hamper patient and provider conversations about pain management, are prominent issues facing efforts to improve pain management, assuring systems are appropriately resourced (eg, standing up new nonpharmacological pain management services, ensuring programs have adequate capacity) and have policies in place to facilitate access (eg, having travel vouchers to help patients access resources, using nonrestrictive eligibility criteria to lessen burdens on patients and providers, and ensuring services with availability in the evenings or weekends) are challenges for health care systems moving forward. The VA as a system has made some gains in increasing utilization of non-opioid pain treatment and continues to work to improve uptake of and Veteran access to these therapies and services.41

In our study, one of the key facilitators to patients’ positive self-management was continuing and building on the self-management strategies learned during EVP. Craner et al42 found that patients value gaining practical skills that they can apply in their lives. Some veterans noted that a barrier to sustaining those self-management practices was not feeling like they had enough experience with them by the time the intervention ended. It seemed important that EVP offered many in class opportunities to engage in hands-on, memorable activities to introduce ideas and practices and that patients had reinforcement practicing those skills while still in the program in order to carry them on once the program was over.

Gilliam et al noted that,19 after leaving programs such as EVP, patients are challenged to apply what they have learned to their life worlds and to use self-management techniques amid different stressors. Participants in our evaluation described these challenges and argued that there was a need for more follow-up support. Gilliam et al suggested plans for follow-up care, and identification of supports and barriers be built in components of multidisciplinary pain programs. Several follow-up options (eg, weekly mindful movement class, ACT for sleep course) have been added to EVP; however, these have experienced low utilization rates. EVP staff are challenged by how best to offer follow-up support in ways that will not overstretch limited resources and that will reach Veterans. Leveraging existing resources and making efforts into ensuring better handoffs and coordination of care with longer term VA providers in primary care and mental health might offer a solution. However, that necessitates ensuring that other VA providers have the knowledge, skills, time, and willingness to offer such support. These challenges are not unique to EVP and require more study as interdisciplinary pain management programs are implemented to address gaps in health system effective pain management resources.

Bremander et al24 found that social support was an important component to Veterans’ experience in EVP. After graduating, participants missed the social support they received from other Veterans while in the program. It is possible in the future that peers might be used to provide after program support and reinforcement. Matthias et al43 found that Veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain benefited from a peer-supported pain management program. Veterans who participated identified several key areas that impressed the most impact: establishing interpersonal connections, receiving or giving encouragement and support, and providing a venue for using self-management strategies.44 These elements overlap with themes noted in our data, suggesting that these may be important program components for pain programming involving peers.

This work is limited by a number of factors. As a quality improvement project, our intention was to not generate generalizable knowledge, but to collect particular knowledge to inform this intervention. Our findings should not be interpreted as representative of other interdisciplinary pain management program outcomes; however, we believe that insights and concerned raised here, especially as related to facilitators and barriers to pain management after leaving EVP, may be of interest and value to those considering or implementing similar programs. As yet there are very little published qualitative data on these topics and we hope our contribution will help spark further discussion and research, we were unable to gage the clinical or functional significance of the outcomes Veterans reported. As a qualitative evaluation, we took the outcomes that participants described to be meaningful to them and thus important. Veterans in our sample may not be representative of all Veterans who have participated in EVP. We anticipate that Veterans with negative experiences with the program would have been less likely to participate in interviews and focus groups. In addition, by design but amplified due to sampling difficulties, we oversampled for Veterans who completed the program. This may have also inflated the degree of reported positive program impacts. We had a hard time recruiting and eventually abandoned efforts to recruit Veterans who had been referred to EVP but had opted not to enroll. Veterans who self-select into EVP might be different than Veterans who did not receive the intervention. We were also unable to detect differences between the outcomes and postprogram experiences of our subsamples. A closer examination of the data using methods such as from grounded theory or examining heterogeneity across other factors (eg, type or intensity of chronic pain, pain-related health care utilization, age, and depression) might have allowed us to tease out important group differences. Understanding the different experiences and challenge Veterans perceive after their program participation is important for continuing QI to adapt EVP to optimize program reach, engagement, and impact of the diverse pool of Veterans it seeks to help.

Conclusion

Veterans described many positive benefits to participating in EVP, including adopting new pain self-management skills, pain acceptance, and a sense of empowerment. Multiple factors could either challenge or support maintenance of outcomes. They identified hands-on experience and reinforcement of practices, access to resources, motivation, and engagement in incremental change as important for experiencing enduring benefits. By contrast, life stressors, lack of proficiency with self-management practices, and inaccessibly or unknown follow-up resources were some barriers to sustaining change. Determining mechanisms for continuing to help patients manage chronic pain for the long term, especially when conditions surrounding their pain shift, remains a challenge for short-term interventions such as this one.

Abbreviations

ACT, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; EVP, Empower Veterans Program; VA, Veterans Affairs

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project was part of ongoing quality improvement work conducted for Empower Veterans Program that was deemed nonresearch and exempt from review by the Veterans Affairs-Emory Institutional Review Board. The project was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. During our recruitment and consent process, all participants were notified of the objectives of the project and how the information they provided would be used and assured confidentiality. Participants provided verbal consent to participate and to audio recording. Written consent was not deemed necessary by the research team as this was not research, there was minimal risk, and not recording participants’ names lessened the risk of participants being identified.

Availability of data and material

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because of the need to preserve the anonymity of the participants. Anonymity would potentially be at risk because of the personal nature of material elicited during interviews.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the Veterans and Veterans Affairs providers who contributed data for the evaluation, as well as the Empower Veterans Program team and interns who helped provide logistical and informational support during the course of the evaluation. The Veterans Affairs Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation provided funding to cover the lead evaluator’s (LP) time on the project and travel, professional transcription, and recording equipment.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

von Korff M, Kolodny A, Deyo RA, Chou R. Long-term opioid therapy reconsidered. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(5):325. | ||

Manchikanti L, Helm S, Fellows B, et al. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3 Suppl):ES9–ES38. | ||

Deshazo RD, Johnson M, Eriator I, Rodenmeyer K. Backstories on the US opioid epidemic. good intentions gone bad, an industry gone rogue, and watch dogs gone to sleep. Am J Med. 2018;131(6):595–601. | ||

Stanos SP. Stemming the tide of the pain and opioid crisis: AAPM reaffirms its commitment to multidisciplinary biopsychosocial care and training. Pain Med. 2017;18(6):1005–1006. | ||

Gatchel RJ, Mcgeary DD, Mcgeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: past, present, and future. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):119–130. | ||

Gatchel RJ, Mcgeary DD, Peterson A, et al. Preliminary findings of a randomized controlled trial of an interdisciplinary military pain program. Mil Med. 2009;174(3):270–277. | ||

Huffman KL, Rush TE, Fan Y, et al. Sustained improvements in pain, mood, function and opioid use post interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation in patients weaned from high and low dose chronic opioid therapy. Pain. 2017;158(7):1380–1394. | ||

Jeffery MM, Butler M, Stark A, Kane RL. Multidisciplinary Pain Programs for Chronic Noncancer Pain. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2011. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK82511/. Accessed December 8, 2017. | ||

Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:h444. | ||

Stanos S. Focused review of interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation programs for chronic pain management. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16(2):147–152. | ||

Kaiser U, Treede RD, Sabatowski R. Multimodal pain therapy in chronic noncancer pain-gold standard or need for further clarification? Pain. 2017;158(10):1853–1859. | ||

Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, Sprott H. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology. 2008;47(5):670–678. | ||

Mccormick ZL, Gagnon CM, Caldwell M, et al. Short-term functional, emotional, and pain outcomes of patients with complex regional pain syndrome treated in a comprehensive interdisciplinary pain management program. Pain Med. 2015;16(12):2357–2367. | ||

Vowles KE, Witkiewitz K, Sowden G, Ashworth J. Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: evidence of mediation and clinically significant change following an abbreviated interdisciplinary program of rehabilitation. J Pain. 2014;15(1):101–113. | ||

Day MA, Brinums M, Craig N, et al. Predictors of responsivity to interdisciplinary pain management. Pain Med. 2017;19(9):1848–1861. | ||

Fedoroff IC, Blackwell E, Speed B. Evaluation of group and individual change in a multidisciplinary pain management program. Clin J Pain. 2013;30(5):399–408. | ||

Dysvik E, Kvaløy JT, Stokkeland R, Natvig GK. The effectiveness of a multidisciplinary pain management programme managing chronic pain on pain perceptions, health-related quality of life and stages of change: a non-randomized controlled study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(7):826–835. | ||

Guzmán J, Esmail R, Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, Irvin E, Bombardier C. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: systematic review. BMJ. 2001;322(7301):1511–1516. | ||

Gilliam WP, Craner JR, Cunningham JL, et al. Longitudinal treatment outcomes for an interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation program: comparisons of subjective and objective outcomes on the basis of opioid use status. J Pain. 2018;19(6):678–689. | ||

Guildford BJ, A D-E, Hill B, Sanderson K, Mccracken LM. Analgesic reduction during an interdisciplinary pain management programme: treatment effects and processes of change. Br J Pain. 2017;204946371773401. | ||

Ravenek MJ, Hughes ID, Ivanovich N, et al. A systematic review of multidisciplinary outcomes in the management of chronic low back pain. Work. 2010;3:349–367. | ||

Spinord L, Kassberg AC, Stenberg G, Lundqvist R, Stålnacke BM. Comparison of two multimodal pain rehabilitation programmes, in relation to sex and age. J Rehabil Med. 2018;50(7):619–628. | ||

Donath C, Dorscht L, Graessel E, Sittl R, Schoen C. Searching for success: Development of a combined patient-reported-outcome (“PRO”) criterion for operationalizing success in multi-modal pain therapy. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):272. | ||

Bremander A, Bergman S, Arvidsson B. Perception of multimodal cognitive treatment for people with chronic widespread pain-changing one’s life plan. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31(24):1996–2004. | ||

Wideman TH, Boom A, dell’elce J, et al. Change narratives that elude quantification: a mixed-methods analysis of how people with chronic pain perceive pain rehabilitation. Pain Res Manag. 2016;2016:9570581. | ||

Bair MJ, Matthias MS, Nyland KA, et al. Barriers and facilitators to chronic pain self-management: a qualitative study of primary care patients with comorbid musculoskeletal pain and depression. Pain Med. 2009;10(7):1280–1290. | ||

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. FY 2019/FY 2017 Annual Performance Plan and Report (APP&R); 2018. Available from: https://www.va.gov/oei/docs/VA2019appr.PDF. Accessed October 19, 2018. | ||

Guest G, Bunce a, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. | ||

Guest G, Namey E, Mckenna K. How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for Nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods. 2016;29(1):3–22. | ||

Burgess-Allen J, Owen-Smith V. Using mind mapping techniques for rapid qualitative data analysis in public participation processes: using mind mapping in analysis of qualitative data. Health Expect. 2010;13(4):406–415. | ||

Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2015. | ||

Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(6):855–866. | ||

QSR International. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software. QSR International Pty Ltd; 2016. | ||

Saldaña J. Coding and analysis strategies. In: Leavy P, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014:581–605. | ||

Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods. 2003;15(1):85–109. | ||

Giannitrapani KF, Ahluwalia SC, Mccaa M, Pisciotta M, Dobscha S, Lorenz KA. Barriers to using nonpharmacologic approaches and reducing opioid use in primary care. Pain Med. 2017 20 Oct 2017. | ||

Becker WC, Dorflinger L, Edmond SN, Islam L, Heapy AA, Fraenkel L. Barriers and facilitators to use of non-pharmacological treatments in chronic pain. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):41. | ||

Becker WC, Mattocks KM, Frank JW, et al. Mixed methods formative evaluation of a collaborative care program to decrease risky opioid prescribing and increase non-pharmacologic approaches to pain management. Addict Behav. 2018;86:138–145. | ||

Giannitrapani K, Mccaa M, Haverfield M, et al. Veteran experiences seeking non-pharmacologic approaches for pain. Mil Med. 2018;183(11–12):e628–e634. | ||

Kennedy LC, Binswanger IA, Mueller SR, et al. “Those conversations in my experience don’t go well”: a qualitative study of primary care provider experiences tapering long-term opioid medications. Pain Med. 2018;19(11):2201–2211. | ||

Frank JW, Carey E, Nolan C, et al. Increased nonopioid chronic pain treatment in the Veterans Health administration, 2010–2016. Pain Med. 2018;18(3). | ||

Craner JR, Skipper RR, Gilliam WP, Morrison EJ, Sperry JA. Patients’ perceptions of a chronic pain rehabilitation program: changing the conversation. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(5):879–883. | ||

Matthias MS, Mcguire AB, Kukla M, Daggy J, Myers LJ, Bair MJ. A brief peer support intervention for veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a pilot study of feasibility and effectiveness. Pain Med. 2015;16(1):81–87. | ||

Matthias MS, Kukla M, Mcguire AB, Bair MJ. How do patients with chronic pain benefit from a peer-supported pain self-management intervention? A qualitative investigation. Pain Med. 2016;17(12):2247–2255. |

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.