Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 16

Prevalence, Reasons and Determinants of Patients’ Nondisclosure to Their Doctors in Saudi Arabia: A Community-Based Study

Authors Alrasheed AA, Alharbi AH, Alotaibi AF, Alqarni AH , Alshahrani AM, Almigbal TH , Batais MA

Received 4 November 2021

Accepted for publication 15 January 2022

Published 29 January 2022 Volume 2022:16 Pages 245—253

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S347796

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Abdullah A Alrasheed,1,2 Abdulrahman H Alharbi,3 Abdulrahman F Alotaibi,3 Abdulaziz H Alqarni,3 Abdullah M Alshahrani,4 Turky H Almigbal,1– 3 Mohammed A Batais1,2

1Department of Family and Community Medicine, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 2Department of Family Medicine, King Saud University Medical City, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 3Vision College of Medicine, Vision Colleges in Riyadh, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 4Department of Family Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Bisha, Bisha, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence: Abdullah A Alrasheed

Department of Family and Community Medicine, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

, Tel +966 55 644 0445

, Email [email protected]

Introduction: Patient–doctor communication is a fundamental component of patients’ care. Withholding important information to the doctor can negatively affect the patients’ health and patient–doctor communication.

Aim: This study aimed to explore the fundamental types of information that patients hide from doctors, eg, the use of medication, health-related lifestyle, or disagreement with the doctor’s plan. In addition, this study examines the prevalence and reasons for this nondisclosure and factors associated with it.

Methodology: An online survey was conducted using a self-designed questionnaire, which was distributed to social media, targeting the residents of Saudi Arabia from February 1, 2021 to February 28, 2021. Respondents under 18 years of age and those who provided incomplete/incorrect data were excluded from the study. Types of nondisclosed information and their reasons were evaluated.

Results: A total of 2725 participants completed the questionnaire, and 1392 (51.1%) were males. About 43.2% of the participants were 18– 29 years. Most (82%) responded “yes” to the question “Have you ever withheld any information from your doctor?” Nondisclosed information commonly involved disagreements with the recommendation (44.7%), not taking prescription medication as instructed (40.6%), and not understanding the instructions (37.4%). The most frequent reasons (68.7%) for nondisclosure were that the participants wanted to undergo further tests, did not like the doctor’s attitude (48.7%) and felt it did not matter to the doctor (43.2%). Those under 40 were more apt to withhold information (70.4%) than older participants (29.6%) p value = 0.0034. Other factors like gender, education level, and marital status were not associated with nondisclosure.

Conclusion: The prevalence of nondisclosure to doctors is high. Effective communication skills and sound doctor–patient relationships may reduce this risk and improve the care delivered to the patients.

Keywords: nondisclosure, patient–doctor relationship, patient doctor communication, shared decision

Introduction

The doctor–patient relationship is an important clinical and psychosocial interaction, which involves vulnerability and trust, and directly impacts the quality of care.1 This relation has been defined as “a consensual relationship in which the patient knowingly seeks the physician’s assistance, and the physician knowingly accepts the person as a patient”.2 The doctor–patient relationship involves a complex interplay whereby a patient trusts a doctor to provide an accepted standard of health care. There are four important elements: trust, knowledge, loyalty, and regard, which build the basis for doctor–patient relationships.3 In medical ethics, the obligations of doctors include beneficence, nonmaleficence, autonomy and justice.4 In this context, the doctor takes informed consent, states the truth about the patient’s condition, and maintains confidentiality. Effective communication skills of doctors play an important role in building a positive doctor–patient relationship, resulting in improved clinical outcomes.5

Sometimes, patients may hide information from doctors to avoid punishment, maintain autonomy, and avoid stigmatization.6,7 Another factor associated with patient nondisclosure is that they feel embarrassed being lectured or judged in their file. Therefore, they do not disclose parts of the information important to reach a final diagnosis and treatment strategy. The patients may hide information related to their prior treatments, overdosing of drugs, or use of illicit drugs.8 Unfortunately, such nondisclosure may mislead the doctors, resulting in a poor clinical outcome and loss of the patient’s trust. Therefore, effective communication between the patient and the doctor is vital to the development of a value-based and trustworthy relationship between the two parties. Effective communication builds and maintains mutual trust between the patient and the doctor, decreases medical errors and medical negligence, improves the patient’s compliance to the treatment, and allows for a better clinical outcome.2

Only a limited number of international studies have broadly investigated the prevalence and reasons of patients’ nondisclosure.9 In addition, there is lack of such research in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, the present study was conducted to explore the fundamental types of information that patients hide from doctors, eg, the use of medication, health-related lifestyle, or disagreement with the doctor’s plan. This study examines the prevalence and reasons for this nondisclosure and factors associated with it.

Methodology

Study Design and Setting

A cross-sectional quantitative study targeting the residents of Saudi Arabia was conducted to determine the prevalence of patients withholding information to their doctors. The study protocol was finalized after receiving approval from the Institutional Review Board at the College of Medicine, King Saud University (Project No. E-20-5508). This study was performed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

A specific questionnaire was designed and distributed to social media (using personal contact and social media platforms such as Twitter, WhatsApp, Instagram, and LinkedIn) (February 1, 2021 - February 28, 2021), targeting the residents of Saudi Arabia. Informed consent and the aim of the study were included in the questionnaire. Participation in the study was voluntary, and the identity of the participants was kept confidential. There is no conflict of interest to disclose. Inclusion criteria included the voluntary participation of those who were over 18 years old and live in Saudi Arabia. Respondents under 18 or those who provided incomplete or incorrect data were excluded from the study.

Survey Instrument

A specific questionnaire was designed in-house. The initial draft was created after an extensive review of the literature on nondisclosure of information by patients.9–11 The questionnaire assessed several common contexts in which a patient might fail to disclose relevant information to a doctor. It was reviewed by three family consultants who were expert researchers. A pilot study was conducted to identify any omissions or lack of clarity, and subsequently, several additions and amendments were made. An additional online pilot study of 35 participants was done to ensure the relevance and effectiveness of the questions. The questionnaire was divided into three parts:

- The first part contained questions about patients’ demographic data, such as age, gender, level of education, and marital status.

- The second part consisted of ten Yes/No questions to evaluate the types of information that remained nondisclosed. Specifically, it asked whether participants had “ever avoided telling a doctor…” This part continued with the reasons (i) Disagreed with the recommendation of the doctor, (ii) Did not understand the instructions of the doctor, (iii) Did not take prescription medication as instructed, (iv) Took someone else’s prescription medication, (v) Had unhealthy diet, (vi) Did not exercise regularly, (vii) Had unhealthy sleep, (viii) Using complementary and alternative medicine, (ix) Following up with same complaint at a different hospital, and (x) had a previous diagnosis or related symptoms. All participants answered each of the ten questions.

- The third part consisted of 18 questions to assess the reason for withholding the information. The participants were asked to choose the most appropriate reason for not telling the doctors across types of information by patients who reported withhold of information from the doctor. The participants were able to choose more than one answer. The questions covered most of the literature reported reasons for not telling doctors across types of information, such as – but not limited to - the desire to do more tests, not feeling comfortable for the doctor’s attitudes, being embarrassed to tell the doctor, the desire not to feel weak, fear of being asked to do difficult changes to behavior and many other reasons as shown in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Selected Reasons for Not Telling the Doctors Across Types of Information by Patients Who Reported Withhold of Information from the Doctor |

Statistical Analysis

We exported the collected data into the Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) (v. 26.0 IBM Corp.). We used the descriptive statistics (mean, frequencies, and percentages) for both the demographic data and each question to describe quantitative and categorical variables. We used the descriptive statistics to identify the percentage of participants who revealed nondisclosure to doctor for each of the ten types of medically relevant information (second part of the questionnaire) and their reason for doing so. We used the Chi-square test of independence to identify statistical differences between patients who disclosed at least one piece of given information with patients who never did. Finally, we used a significance level of (α≤0.05) as the statistical threshold in this study.

Results

The Study Population

A total of 2725 participants completed the questionnaire of which 1392 (51.1%) were males. The majority of participants were 18–29 years old (43.2%) followed by the age group of 30–39 years (25.9%). A total of 1557 (57.13%) were married; 1057 (38.7%) were single; 86 (3.1%) were divorced; and 25 (0.9%) were widowed. The majority of participants had bachelor’s degrees or diplomas (62.1%), followed by high school level (24.6%), higher education level (10.2%), and middle school or below (2.6%) level of education as shown in Table 2.

|

Table 2 Participants’ Demographics (n=2725) |

The Prevalence of Nondisclosure to the Doctor

A majority of the participants (82.6%) responded “yes” to the question regarding “ever avoid telling any information to the doctor?” The most common type of information withheld from the doctor was disagreement with recommendation of the doctor (44.7%). More than one-third of the participants responded “yes” to the statement, “Did not take prescription medication as instructed” (40.6%) and “did not understand instructions of the doctor” (37.4%). [Table 3]. Participants hid information related to an unhealthy diet (31%), while 29% withheld information about not exercising regularly, and 27% did not admit their unhealthy sleep patterns. Similarly, about one-fourth of the patients (26%, 24%, 22%, and 24%) did not disclose information about having a previous diagnosis or related symptoms, using complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), taking someone else’s prescription, and following-up with the same complaint but at different hospital, respectively [Table 3].

|

Table 3 Types of Information Not Disclosed to the Doctor |

Reasons Behind Nondisclosure to the Doctor

The most frequent reason (68.7%) given for withholding information to doctors was that the participants wanted to undergo more tests first [Table 1]. The second most common reason for nondisclosure was not liking the doctor’s attitude (48.7%). In addition, 43% participants did not disclose their information to the doctor as they did not want their companion to know about their health issue or they thought that the information would not matter to the doctor. Other reasons for withholding or avoiding telling the doctor about the information have been provided in Table 1.

Which Patients Tend to Hide Information from the Doctor?

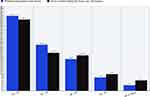

Younger participants (< 40 years) tend to avoid telling the doctor their medically relevant information (70.4%) more than older participants (≥ 40 years) (63.6%), and this difference was statistically significant (p=0.0034). However, the study findings revealed that there was no significant association between patients’ sex, marital status, and level of education and their nondisclosure of information to their doctors as shown in Table 4. More details about the participants’ age and not providing information is shown in Figure 1.

|

Table 4 Comparison Between Patients Who Disclose at Least One Bit of Information with Patients Who Never Did |

|

Figure 1 The percentages of participants who avoided telling the doctor and those who never withheld information according to age group. |

Discussion

The present study was conducted to determine the prevalence and the types of information the participants may hide from doctors and the reasons for this nondisclosure. The study revealed that a majority of participants had hidden information from their doctors at some point in their life. The most common types of nondisclosed information related to disagreements with the recommendations of the doctor, not taking the medications as prescribed, and not understanding the instructions of the doctor. The most common reason for withholding information was that the participants wanted to undergo more tests first.

Studies revealed that patients may hide information related to their condition, affecting both their clinical outcome and doctor–patient relationship. Therefore, it is obligatory for the patients to be forthcoming about their illness or disease to reach an accurate diagnosis and proper management. Many times, patients did not disclose information when they misunderstood or disagreed with the doctor’s instructions. However, patients might not disclose information for their doctors to avoid being vulnerable through sharing their personal life, health, worries, uncertainties, etc. Making Care Fit Manifesto requires patients or their significant loved ones to collaborate with the doctor. For care to be fit, the doctor should respond at a maximum to the patient’s situation, support his/her priorities, ensure minimum disruption of patient’s life or patient’s social network.

Levy et al9 conducted two national online surveys in the USA to determine the prevalence and associated factors with patient nondisclosure of illness-related information to their doctors. They reported that participants mostly hid the information when they disagreed with the doctor’s recommendations and did not disclose information, because they misunderstood the doctor’s instructions. Similarly, in the present study, a similar percentage of participants avoided telling their doctors when they disagreed with their recommendations, and a similar percentage did so when they did not understand the doctor’s instructions. However, the main reason for withholding information in the USA was related to not wanting to be judged or lectured by the doctor (64.1% to 81.8%). However, our study showed lower percentage withheld information for this reason.

In the same surveys, conducted by Levy et al, 60–80% of respondents admitted that they avoided disclosing information related to their health conditions. This is in a line with the results describes in the present study in which a majority of patients admitted that they withheld information to their doctors. In the American surveys, more than one-third of the respondents did not disclose that they disagreed with the doctor’s advice or could not understand the doctor’s instructions. Similarly, more than one fifth of respondents hid the fact that they ate an unhealthy diet or did not regularly exercise. Therefore, the doctors need to earn their patients’ confidence in order to capture complete information from their patients. The patients’ confidence can be gained via developing good doctor–patient relationships in which the doctor and the patient mutually share their concerns about the health care. The patients should disclose complete information to their doctors, and the doctors should explain all aspects of the illness to their patients. Nondisclosure from either side compromises the quality of care.6,9

Several reasons why patients withhold information to their doctors have been identified. The most frequent reasons for this nondisclosure include fear of punishment, rejection, humiliation, not wanting to be judged or lectured, preservation of autonomy, repression of conflict, and perception of not being important.6,7,9 On the contrary, in the present study, the most common reason for nondisclosure by the respondents was that they wanted to have more blood tests. One possible explanation for seeking additional testing is the assumption that such tests provide a large amount of information and can detect serious diseases at an early stage with no errors.12 Moreover, minimal awareness about the importance of clinical history and examinations in reaching a diagnosis might be an additional explanation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the patient’s need to test as reason for nondisclosure. This highlights the need for further investigation of this issue in future studies.

In the present study, younger patients withhold information from their doctors more than older patients. This is in a line with the results of the two surveys conducted in USA.9 One study investigated the differences related to the age in doctor–patient interaction, and determined that older patients were more satisfied with the patient-centered care in comparison to their younger counterparts. In addition, doctors are more likely to practice patient-centered encounters with the elderly population.13 This association between age and doctor–patient interaction might affect the patient nondisclosure. This is supported by “not liking the doctor’s attitude” as the second most common reason for nondisclosure reported in this study.

Nondisclosure of important information from the patients to doctors greatly affects the communication skills. There is a complex interplay between doctors and patients, which leads to vulnerability and trust.14 Effective communication further facilitates the patient’s comprehension, and enhances the understanding of a patient’s emotions, needs, and expectations.15 Likewise, poor communication skills may result in serious misunderstandings, compromising patient’s trust, expectations, safety and quality of care.16

One advantage of the present study is that it opens researchers’ eyes to the most common reasons of nondisclosure on the part of patients which can be improved via certain strategies, such as effective communication skills and a sound doctor–patient relationship. However, the present study limitations include an online questionnaire-based survey, which may lead to respondents’ bias. Furthermore, an online survey will not represent the entire population, and we believe patients who withhold information from their doctor might have avoided participation in the study. As a result, our results could be less than the actual prevalence. In addition, more details about nondisclosure, such as frequency and the medical specialty, were not included in our study and might be considered in future research.

A significant implication of the present study is the research implications as the results of the present study might provide baseline data for future researchers to perform a systematic examination of the effect of patient’s characteristics on nondisclosure of information to doctors. These characteristics might include the probable severity of consequences of non-disclosing information to doctors or the levels of stigmatizing a specific health behavior. With regard to practical implications, this work might attract the attention of doctors to adopt Making Care Fit manifesto when retrieving information from patients.

Conclusion

The present study reveals that a high prevalence of patients in Saudi Arabia tend to hide clinical information from their doctors based on several reasons. Effective communication skills and good doctor–patient relationship can build patients’ trust in doctor, reducing the risk of nondisclosure and improving clinical outcomes.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Razzaghi MR, Afshar L. A conceptual model of physician-patient relationships: a qualitative study. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2016;9:14.

2. Honavar SG. Patient–physician relationship – communication is the key. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66(11):1527–1528. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_1760_18

3. Chipidza FE, Wallwork RS, Stern TA. Impact of the doctor-patient relationship. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(5). doi:10.4088/PCC.15f01840

4. Varkey B. Principles of clinical ethics and their application to practice. Med Princ Pract. 2021;30(1):17–28. doi:10.1159/000509119

5. Ranjan P, Kumari A, Chakrawarty A. How can doctors improve their communication skills? J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2015;9(3):JE01. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2015/12072.5712

6. Palmieri JJ, Stern TA. Lies in the doctor-patient relationship. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(4):163–168. doi:10.4088/PCC.09r00780

7. Levy AG, Scherer AM, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Larkin K, Barnes GD, Fagerlin A. Assessment of patient nondisclosures to clinicians of experiencing imminent threats. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e199277. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.9277

8. Fainzang S. Lying, secrecy and power within the doctor-patient relationship. Anthropol Med. 2002;9(2):117–133. doi:10.1080/1364847022000034574

9. Levy AG, Scherer AM, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Larkin K, Barnes GD, Fagerlin A. Prevalence of and factors associated with patient nondisclosure of medically relevant information to clinicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e185293. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5293

10. Ismail WI, Hassali MA, Farooqui M, Saleem F, Roslan MN. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) disclosure to health care providers: a qualitative insight from Malaysian thalassemia patients. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;33:71–76. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.06.004

11. Meyer WJ, Morrison P, Lombardero A, Swingle K, Campbell DG. College students’ reasons for depression nondisclosure in primary care. J Coll Stud Psychother. 2016;30(3):197–205. doi:10.1080/87568225.2016.1177435

12. Van Bokhoven MA, Pleunis-van Empel MC, Koch H, Grol RP, Dinant GJ, van der Weijden T. Why do patients want to have their blood tested? A qualitative study of patient expectations in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-7-75

13. Peck BM. Age-related differences in doctor-patient interaction and patient satisfaction. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2011;2011:1–10. doi:10.1155/2011/137492

14. Ha JF, Longnecker N. Doctor-patient communication: a review. Ochsner J. 2010;10(1):38–43.

15. Arora N. Interacting with cancer patients: the significance of physicians’ communication behavior. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(5):791–806. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00449-5

16. Vermeir P, Vandijck D, Degroote S, et al. Communication in healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(11):1257–1267. doi:10.1111/ijcp.12686

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.