Back to Journals » Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity » Volume 7

Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its components based on a harmonious definition among adults in Morocco

Authors El Brini O, Akhouayri O, Gamal A, Mesfioui A, Benazzouz B

Received 28 January 2014

Accepted for publication 19 March 2014

Published 31 July 2014 Volume 2014:7 Pages 341—346

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S61245

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 5

Video abstract presented by Omar Akhouayri.

Views: 489

Otmane El Brini,1 Omar Akhouayri,1 Allal Gamal,2 Abdelhalem Mesfioui,1 Bouchra Benazzouz1

1Laboratory of Genetic, Neuroendocrinology and Biotechnology, University Ibn Tofail, Faculty of Sciences, Kenitra, Morocco; 2Diagnostic center, Rabat, Morocco

Purpose: Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular diseases that includes central obesity, hypertension, glucose intolerance, high triglyceride, and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Its prevalence is rapidly increasing worldwide. This study aimed to estimate the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and associated risk factors in a representative sample of Morocco adults using the 2009 joint interim statement definition.

Patients and methods: We analyzed data of 820 patients aged 19 years and older. For metabolic syndrome diagnosis, we used the criteria of the recently published joint interim statement (2009).

Results: The prevalence of metabolic syndrome is 35.73% among all adults, 18.56% among men, and 40.12% among women. Prevalence increased with age, peaking among those aged 50–59 years. The most common abnormality highlights abdominal obesity (49.15%). Also, half of patients have one or two risk factors for developing this syndrome.

Conclusion: The prevalence of metabolic syndrome and associated risk factors is high among adults in Morocco, especially in women. The most prevalent component of metabolic syndrome in our population was abdominal obesity.

Keywords: central obesity, hypertension, glucose intolerance, triglyceride, cholesterol

Introduction

The rapid Moroccan economic growth in recent decades has created drastic changes in the lifestyle of the Moroccan population.1 Excess energy intake and sedentary lifestyle is becoming widespread in the population, and is raising metabolic risk factors such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension to the epidemic level.2,3

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a group of interrelated risk factors of metabolic origin that appear to directly promote the development of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and also type 2 diabetes mellitus.4,5 It combines central obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, hypertension, and impaired glucose tolerance.6 In some studies, MetS is associated with a threefold increased risk of coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, and stroke,7 and a three- to fivefold increased risk of cardiovascular death,8,9 even after adjustment for conventional risk factors.10 Thus, it constitutes a full-fledged epidemic.11,12

MetS is present in 38.5% of US adults,13 21.1% of the French population,14 and 27.8% of the Spanish population15 (by the joint interim statement definition).16 Among Arab populations, the prevalence estimates are 30.0% in Tunisia,17 21% in Saudi Arabia,18 and 36.3% in Jordan19 (by the third adult treatment panel of the National Cholesterol Education Program definition).20 In Morocco, studies on the distribution of individual components of MetS were performed, and their results showed a high prevalence of these risk factors for cardiovascular disease in the Moroccan population.21,22 However, studies on the distribution and prevalence of MetS as an emergent entity that includes these risk factors are very limited.

This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of MetS and its individual components in an adult Moroccan population using the harmonious definition issued from the guidelines of the 2009 Joint Scientific Statement.16

Materials and methods

Patients and methods

This was a retrospective study based on the analysis of the files of 820 adult patients (653 women and 167 men) consultants at the center of diagnosis of Rabat during a period of 20 months (October 2010 to May 2012).

The file analyses consisted on exploitation of: 1) anthropometric parameters (the age and the waist circumference, which allows the evaluation of the abdominal obesity of the patient); and 2) the results of the measurement of blood pressure and the dosage of biochemical parameters (glycemia, triglyceridemia, total cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol).

Definition of MetS

We used the recently published joint interim statement endorsed by the International Diabetes Federation Task Force and several other international and national organizations to define MetS.16 This definition allows harmonization and comparison between international research laboratories.

The consensus criteria define MetS as the presence of three or more of the following metabolic risk factors:

- Elevated waist circumference (population- and country-specific cut-offs: ≥94 cm for men and ≥80 cm for women).

- Elevated triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL (1.69 mmol/L).

- Reduced HDL cholesterol (<40 mg/dL [1.04 mmol/L] in men, and <50 mg/dL [1.29 mmol/L] in women).

- Elevated blood pressure (systolic ≥130 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥85 mmHg).

- Elevated fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL (5.56 mmol/L).

Individuals who report using drug treatments for any of the above medical conditions are considered to meet the criteria for the specific component.

Statistical analysis

For the purpose of statistical analysis, age was categorized into five intervals (19–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, and ≥60 years) to estimate age-adjusted prevalence rates by direct method23 using the World Standard Population.24 The chi-square test was performed to compare the crude prevalence rate between men and women. The analyses reported in this study were performed using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

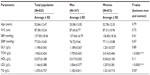

The files for a total of 820 patients (653 women and 167 men) aged 19 years and older were examined. The anthropometric and metabolic characteristics of the studied population are summarized in Table 1. The average age of the population was 52.84±12.47 years. Total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), and triglyceridemia were significantly higher among women compared to men (P<0.05).

Distribution of MetS and its components

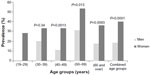

Table 2 shows the variation in the prevalence of MetS by sex and age in the study population. The prevalence of MetS was 35.73% with a highly significant female predominance (40.12% for women and 18.56% for men; P<0.0001). The data show an increase of MetS prevalence with age. A decline in this prevalence was observed in patients aged 60 years and over (Figure 1). The highest prevalence of MetS was found in patients aged 50–59 years for both sexes.

| Table 2 Variation in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome by sex and age group in the entire population |

| Figure 1 Variation in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome by sex and age group in the total population. |

We then examined the distribution of the different risk factors associated with MetS in our population by sex and age group (Table 3). According to these results, in the entire population and in the women’s group, the most common abnormality was abdominal obesity, which affected around half of the population (49.15% and 56.81%, respectively). The same conclusion was found by using the logistic regression (data not shown). The model suggests that abdominal obesity is the strongest predictor of MetS in our study population.

| Table 3 Variation in the frequency (%) of risk factors associated with metabolic syndrome by sex and age group in the population |

In men, low HDL cholesterol had the highest frequency. In addition, the majority of abnormalities associated with MetS were expressed in their highest frequencies in patients of the 50–59 years age group.

Distribution of the number of risk factors of metabolic syndrome

In order to assess the risk linked to the presence of metabolic abnormalities associated with MetS in our study population, we examined the distribution of the number of risk factors according to sex and age group (Table 4). In our population, 85.5% had at least one metabolic abnormality; those with one or two risk factors represent 49.76% of the population and are at risk of developing MetS. The population aged 50–59 years accumulated more risk factors compared to the other age groups. Severe MetS (four or more associated anomalies) was represented by 14.70% and 4.79% of women and men, respectively.

| Table 4 Distribution (%) of the number of risk factors associated with metabolic syndrome by sex and age group in the population |

Discussion

MetS has become a public health problem, the prevalence of which is increasing worldwide.12,25 To our knowledge, this is the first Moroccan study that focuses on the estimation of the prevalence of MetS in the general population by using the 2009 joint interim statement definition.16 The prevalence found in our population was 35.73%. This result is consistent with results from other studies, where the prevalence of MetS was 38.5% among Americans13 and of 33.5% in the population of India.26 However, it is high compared to prevalence in the South African population27 (25.5%) and lower than that of the Greek population28 (45.7%) and the population of Nepal29 (61.7%). These differences in the prevalence of MetS can be explained by the interaction of genetic and environmental factors,19 which have long been known to play a key role in the pathophysiology of MetS.30 Furthermore, analysis of the variation in prevalence of MetS according to sex showed a significantly higher prevalence in females (40.12%) compared to males (18.56%). This result is consistent with many studies;4,17,26 however, it differs from others where the prevalence is similar between both sexes.31 The use of more stringent thresholds of abdominal obesity imposed by the definition,16 as well as metabolic changes that occur with menopause,32 may partly explain the high prevalence of MetS in women. This is evidenced by an abdominal obesity affecting 56.81% of our female population. This risk factor was present in 70.41% of women aged 50–59 years, where the prevalence of MetS was 53.57%. In addition, we observed a variation in the prevalence of MetS according to age with a maximum at the sixth decade among men and women (respectively, 31.6% and 53.6%). This can be explained by the changes in certain anthropometric and metabolic parameters occurring with age, such as body measurements of fat distribution and insulin sensitivity.33 A decline is observed in the prevalence of MetS in patients aged over 60 years. This may be related to mortality of syndromic people of the 50–59 years age group. Indeed, the association between premature mortality and the presence of MetS has been described in many studies.5,7 In terms of risk, Sattar suggested that the global risk associated with MetS depends on the number of risk factors used to define this syndrome.34 Our study population appears to be at high risk of developing MetS as half of the patients (49.76%) have one or two risk factors. In addition, if the severity of MetS can be described by the number of components, then 12.68% of our patients have severe MetS, which impact is an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. There are several points that should be considered when examining the results of this study:

- The female predominance in our study population related to social factors manifesting in the tendency for women to seek consultation more than men.

- The unbalanced distribution of patients between certain age classes, particularly in the group of men aged 19–29 years that contained only six patients who were not syndromic.

Conclusion

The results of this study, using the criteria of the new harmonized definition, allowed an estimation of the prevalence of MetS in a Moroccan adult population. MetS and its components were common, especially abdominal obesity, which appears to be the central abnormality in the genesis of MetS. This finding will contribute to mapping MetS in the world and describing its prevalence in various populations.

Significant heterogeneity exists between men and women because of the abdominal obesity and metabolic changes that occur with menopause. The emphasis for all studies and programs related to MetS should be focused on prevention, early detection of metabolic risk factors, and interventions that will have a significant impact on future adult health.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Benjelloun S. Nutrition transition in Morocco. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:135–140. | |

El ayachi M, Mziwira M, Vincent S, et al. Lipoprotein profile and prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in urban Moroccan women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:1379–1386. | |

Essiarab F, Taki H, El Malki A, Hassar M, Saile R, Ghalim N. Cardiovascular risk factors prevalence in a Moroccan population. Eur J Sci Res. 2011;49(4):581–589. | |

Jesmin S, Islam MR, Islam AM, et al. Comprehensive assessment of metabolic syndrome among Rural Bangladeshi Women. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:49. | |

Katzmarzyk PT, Church TS, Blair SN. Cardiorespiratory fitness attenuates the effects of the metabolic syndrome on all cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1092–1097. | |

Reaven GM. Banting lecture 1988: role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37:1595–1607. | |

Isomaa B, Almgren P, Tuomi T, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:683–689. | |

Haffner SM, Valdez RA, Hazuda HP, Mitchell BD, Morales PA, Stern MP. Prospective analysis of the insulin resistance syndrome (syndrome X). Diabetes. 1992;41:715–722. | |

Mykkänen L, Kuusisto J, Pyörälä K, Laakso M. Cardiovascular disease risk factors as predictors of type 2 (non-insulindependent) diabetes mellitus in elderly subjects. Diabetologia. 1993;36:553–559. | |

Lakka HM, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA, et al. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA. 2002;288:2709–2716. | |

Kereiakes DJ, Willerson JT. Metabolic syndrome epidemic. Circulation. 2003;108:1552–1553. | |

Grundy SM. Metabolic syndrome pandemic. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:629–636. | |

Ford ES, Li C, Zhao G. Prevalence and correlates of metabolic syndrome based on a harmonious definition among adults in the US. J Diabetes. 2010;2:180–193. | |

Vernay M, Salanave B, de Peretti C, et al. Metabolic syndrome and socioeconomic status in France: The French Nutrition and Health Survey (ENNS, 2006–2007). Int J Public Health. 2013;58:855–864. | |

Corbatón-Anchuelo A, Martínez-Larrad MT, Fernández-Pérez C, et al. Metabolic syndrome, adiponectin, and cardiovascular risk in Spain (the Segovia study): impact of consensus societies criteria. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2013;11(5):309–318. | |

Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–1645. | |

Belfki H, Ben Ali S, Aounallah-Skhiri H, et al. Prevalence and determinants of the metabolic syndrome among Tunisian adults: results of the Transition and Health Impact in North Africa (TAHINA) project. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16:582–590. | |

Alzahrani AM, Karawagh AM, Alshahrani FM, Naser TA, Ahmed AA, Alsharef EH. Prevalence and predictors of metabolic syndrome among healthy Saudi Adults. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis. 2012;12:78–80. | |

Khader Y, Bateiha A, El-Khateeb M, Al-Shaikh A, Ajlouni K. High prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among Northern Jordanians. J Diabetes Complications. 2007;21:214–219. | |

National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143–3421. | |

Tazi MA, Abir-Khalil S, Chaouki N, et al. Prevalence of the main cardiovascular risk factors in Morocco: results of a National Survey, 2000. J Hypertens. 2003;21:897–903. | |

Aparicio VA, Ortega FB, Carbonell Baeza A, et al. Fitness, fatness and cardiovascular profile in South Spanish and North Moroccan women. Nutr Hosp. 2011;26:1188–1192. | |

King H, Rewers M. Global estimates of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in adults. WHO Ad Hoc Diabetes Reporting Group. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:157–177. | |

Segi M. Cancer Mortality for Selected Sites in 24 Countries (1950–57). Sendai: Department of public health, Tohoku University school of Medicine; 1960. | |

Duncan GE, Li SM, Zhou XH. Prevalence and trends of a metabolic syndrome phenotype among us Adolescents, 1999–2000. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2438–2443. | |

Prasad DS, Kabir Z, Dash AK, Das BC. Prevalence and risk factors for metabolic syndrome in Asian Indians: A community study from urban Eastern India. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2012;3:204–211. | |

Motala AA, Esterhuizen T, Pirie FJ, Omar MA. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and determination of the optimal waist circumference cutoff points in a rural South african community. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1032–1037. | |

Anagnostis P. Metabolic syndrome in the Mediterranean region: Current status. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:72–80. | |

Maharjan BR, Bhandary S, Shrestha I, Sunuwar L, Shrestha S. Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in Local Population of Patan. Medical Journal of Shree Birendra Hospital. 2012;11:27–31. | |

Poulsen P, Vaag A, Kyvik K, Beck-Nielsen H. Genetic versus environmental aetiology of the metabolic syndrome among male and female twins. Diabetologia. 2001;44:537–543. | |

Santos AC, Severo M, Barros H. Incidence and risk factors for the metabolic syndrome in an urban South European population. Prev Med. 2010;50:99–105. | |

Fujimoto WY, Bergstrom RW, Boyko EJ, et al. Type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome in Japanese Americans. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;50:S73–S76. | |

Carr DB, Utzschneider KM, Hull RL, et al. Intra-abdominal fat is a major determinant of the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria for the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2004;53:2087–2094. | |

Sattar N, Gaw A, Scherbakova O. Metabolic syndrome with and without C-reactive protein as a predictor of coronary heart disease and diabetes in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. Circulation. 2003;108:414–419. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.