Back to Journals » Journal of Blood Medicine » Volume 11

Prevalence of Anemia and Its Associated Factors Among Female Adolescents in Ambo Town, West Shewa, Ethiopia

Authors Tura MR , Egata G, Fage SG , Roba KT

Received 19 May 2020

Accepted for publication 11 August 2020

Published 7 September 2020 Volume 2020:11 Pages 279—287

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JBM.S263327

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Martin H Bluth

Meseret Robi Tura,1 Gudina Egata,2 Sagni Girma Fage,3 Kedir Teji Roba3

1Department of Nursing, College of Medicine & Health Sciences, Ambo University, Ambo, Ethiopia; 2School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 3School of Nursing & Midwifery, College of Health & Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Sagni Girma Fage Email [email protected]

Objective: This study assessed the prevalence of anemia among female adolescents and factors associated with it in Ambo town, West Shewa, Ethiopia.

Materials and Methods: A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 523 randomly selected female adolescents living in Ambo town, Ethiopia from August 5– 29, 2018. Data were collected through structured interview using a structured questionnaire. Anthropometric measurements were done and the hemoglobin value was measured on the field and adjusted for the altitude. Logistic regression analysis was done to identify predictors of anemia. Level of statistical significance was declared at P< 0.05.

Results: In this study, 39% (95% CI= 34.8– 43%) participants were anemic, of which 63 (30.9%) and 46 (22.5%) female adolescents were stunted and wasted, respectively. Anemia was considerably high among female adolescents with high dietary diversity score. Adolescents born to mothers who were unable to read and write (AOR= 3.27; 95% CI=1.79– 5.97), who always take tea and/or coffee within 30 minutes after meal (AOR= 6.19; 95% CI=3.32– 11.48), who were wasted (AOR=1.67; 95% CI=1.11– 2.52), and who had already attained their menses (AOR=1.93; 95% CI=1.19– 3.13) were more likely to be anemic compared to their counterparts.

Conclusion: Nearly four in ten female adolescents in the study setting were anemic. Anemia among female adolescents was a moderate public health problem. Adolescents born to mothers who were unable to read and write, who consumed tea/coffee within 30 minutes after a meal, who were wasted, and who had already attained menses should be prioritized for interventions aiming at addressing iron-deficiency anemia in female adolescents.

Keywords: anemia, female adolescents, West Shewa, Ambo, Ethiopia

Introduction

Anemia is among the major global public health problems with significant adverse health, social, and economic impacts.1 In 2011, it affected 24.8% of the world population with the burden varying across age, sex, altitude, and pregnancy states. Anemia may occur due to a number of causes, and the most significant contributor is iron deficiency.1,2

Anemia is the reduction of red blood cells and/or hemoglobin (Hb) concentration.1,3 Iron-deficiency anemia (IDA) is the most common type of anemia that increases at the start of adolescence. In females, this is caused by increased requirements of nutrition for growth and is exacerbated a few years later by the onset of menstruation.2 Female adolescents are at higher risk for anemia than male adolescents.4 The World Health Organization (WHO) defined adolescence as the period of life spanning the ages between 10–19 years where extra nutrients are needed to support the growth spurt.5,6 In Ethiopia, adolescents constitute about 48% of the population, of which about 25% are female.7

Adolescents are at high risk of iron deficiency and anemia due to the physical and physiological changes that put a higher demand on their nutritional requirements. The rapid pubertal growth with sharp increase in lean body mass, blood volume, and red cell mass, increases iron requirements for myoglobin in muscles and hemoglobin in the blood.2,8 There was highest prevalence of anemia in African region in the presence of factors affecting anemia- such as malaria and sickle cell. Though the global prevalence of anemia has been estimated for other population groups, adolescents are often ignored.1,3

In Ethiopia, anemia among women aged 15–19 years was 13.4% in the 2011 national survey.9 But, the prevalence of anemia among female adolescents reported by different pocket studies varies from place to place and ranges from 11.1–38.3%8,10-13 indicating that there is a gap to be addressed. Improving adolescents’ nutrition is an earlier intervention that helps to break the vicious cycle of malnutrition.2 The interventions and studies on anemia commonly target other population groups, and the needs of adolescents might remain unmet.1,8,10,14,15 Nevertheless, there is limited evidence on the prevalence of anemia and associated factors among female adolescents in low income countries including Ethiopia to design appropriate interventions. Thus, this study aimed at determining the prevalence of anemia and factors associated with it among female adolescents in Ambo town, West Shewa, Ethiopia.

Materials and Methods

Study Setting and Period

The study was conducted in Ambo town, the capital of West Shewa zone of Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. The town is located about 114 km west of the capital, Addis Ababa, on the way to Wollega. Its average altitude is 2101 meters above sea level. According to Ambo town’s administration office report, the town had six kebeles (the smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia). This study was conducted during summer season (August 5–29, 2018) to assure that in-school adolescents were included.

Study Design and Population

We used a community-based cross-sectional study design. All female adolescents (aged 10–19 years) in Ambo town were the source population while randomly selected female adolescents in the randomly selected kebeles of the town were the study population.

Sample Size and Sampling Procedure

The sample size for this study was calculated by using single population proportion formula with the assumptions of: 95% confidence level, 5% margin of error, and the proportion of anemia in female adolescents (32%) taken from a previous study.16 Finally, by considering the design effect of 1.5 and by adding 10% for possible non-response, the final sample size was 551 female adolescents.

To select study participants, first three out of the six kebeles were selected randomly by lottery method. Then, households with at least one female adolescent were identified from family folders obtained from the respective health extension workers (HEWs) of each selected kebele. Next, the sample size was allocated to the selected kebeles proportional to their total households with at least one female adolescent. By considering the list of the households with at least one female adolescent as a sampling frame, a simple random sampling technique was employed to select the households. Where there was more than one female adolescent in the same household, one was selected randomly by lottery method.

Data Collection Tool and Procedure

The data on socio-demographic variables, food frequency, dietary diversity, menstruation history, and deworming were collected by using an interviewer administered pre-tested structured questionnaire developed through a relevant literature review. The data were collected by three medical laboratory technicians through home to home visit and supervised by one Bachelor health officer.

Measurements

To determine nutritional status of adolescents by Body Mass Index for age Z-score (BAZ) and Height for Age Z-score (HFA), weight and height were measured. Weight of adolescents was measured by using a portable digital weight scale with a capacity of 120 kg and recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg, and height was measured by using a portable wooden height board and recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm. Each subject was weighed with light clothing and no footwear. Both anthropometric measurements were collected twice and the average values were used for analysis.17,18

For Hemoglobin (Hb) level determination, 10 µL capillary blood samples were taken by pricking the tip of the finger with a sterile disposable lancet. The first drop of blood was wiped away and the second drop was used for Hb determination. Hemoglobin analysis was carried out using a Hemocue hemoglobin spectrophotometer (Hemocue HB 301 analyzer). A drop of blood was allowed to enter the optical window of the micro cuvette through capillary action.

Dietary diversity practice of participants was assessed using the qualitative tool of Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) for 24 hour dietary recall. The individual dietary diversity score (DDS) of female adolescents was then calculated by summing up the food items into nine food groups and classified as low (1–3 food groups), medium (4–6 food groups) and high (>6 food groups).19

Data Quality Control

The questionnaire was prepared in English, translated to the local languages (Afaan Oromoo and Amharic), and re-translated back into English to check for its consistency. Pre-test was conducted among 26 (5% of the sample size) female adolescents who lived in a nearby town, Ginchi, and modifications were considered accordingly. Training on survey methods, tools, and measurements was given for the data collectors and the field supervisor.

Data Processing and Analysis

The collected data were checked for completeness, cleaned, coded, entered into Epi-data version 3.02, and exported to SPSS for windows version 21 for analysis. Frequency was run to check for any missing values and re-checked from the hard copy where needed. Hemoglobin levels were adjusted for altitude by using the formula: Hb=− 0.32×(altitude in meters×0.0033)+0.22×(altitude in meters×0.0033)2. Anemia and its severity were defined based on the cut-off Hb levels≥11.5 g/dL and 11–11.4 g/dL as no anemia and mild anemia, respectively, for females aged 10–11 years whereas Hb levels of ≥12 g/dL and 11–11.9 g/dL as no anemia and mild anemia, respectively, for those above 12 years of age. In both age groups, we defined moderate and severe anemia as Hb levels 8–10.9 g/dL and <8 g/dL, respectively.3

The outcome variable was recoded into binary as anemia=1 and no anemia=0. WHO AnthroPlus software version 3.1 was used to calculate nutritional status. Based on the global anthropometric classification, female adolescents with BAZ and HAZ score of ≤−2 SD) were considered to be thin (wasted) and stunted (short for age), respectively.

Logistic regression analysis was done to check the association between independent variables and anemia. All variables with a P-value<0.25 in bivariate analysis were candidates for multivariate analysis to control for confounders and to identify independent predictors of anemia. Multi-collinearity was checked by using the standard error and there was no multi-collinearity, thus no variable was dropped from analysis. Odds Ratio along with 95% confidence interval was estimated to measure the strength of association between covariates and anemia. The model fitness was tested by Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test. The level of statistical significance was declared at P<0.05.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Participants

Five hundred and twenty-three female adolescents participated in the study, yielding a 95% response rate. While the remaining 3% declined to give blood for hemoglobin determination, 0.9% of participants were not found after repeated visits and 1.1% refused participation completely. More than half of the study participants, 320 (61.2%), were in the age group of 15–19 years. The mean±SD age of participants was 15.01±2.533 years. Three hundred and eighty-four (73.4%) adolescents reported that they live in a family with a family size of ≤5 members, while the remaining 139 (26.6%) were from a family size of >5. Regarding the family’s average monthly income, 408 (78%), 60 (11.5%), and 55 (10.5%) adolescents reported <500 birr (<18.18 USD), 500–1000 birr (18.18–36.36 USD) and >1000 birr (>36.36 USD), respectively. The majority, 273 (52.2%) were protestant in their religion, while 389 (74.4%) participants were Oromo in their ethnicity. The marital status of 485 (92.7%) participants was single and, as to their educational status, 388 (74.2%) female adolescents attended only primary school (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Female Adolescents and Their Parents in Ambo Town, West Shewa, Ethiopia, 2018 (n=523) |

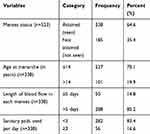

Menstruation Related Characteristics of Female Adolescents

The majority, 338 (64.6%) of the participants had already attained menses, of which 237 (70.1%) attained their menarche at the age of ≤14 years. About 288 (85.2%) females had a history of more than 5 days length of blood flow in each menses period and 282 (83.4%) female adolescents reported they use less than three sanitary pads per day (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Menstruation Related Characteristics of Female Adolescents in Ambo Town, West Shewa, Ethiopia, 2018 |

Nutritional Status of Participants

We found that thinness (BAZ score ≤−2) was 28.5% (95% CI= 24.1–32.7%) and stunting (HAZ score ≤−2) was 29.4% (95% CI=25.6–33.7%) among the study participants. Moreover, 63 (30.9%) and 46 (22.5%) of the anemic female adolescents were stunted (short for their age) and wasted (thin for their age), respectively (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Factors Associated with Anemia Among Female Adolescents in Ambo Town, West Shewa, Ethiopia, 2018 (n=523) |

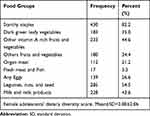

Dietary Diversity Score of Female Adolescents

The minimum and maximum dietary diversity score of the study participants were 1 and 9 respectively with a mean (±SD) score of 3.80±2.06. About 256 (49%) female adolescents had a dietary diversity score of greater than or equal to 4. The most commonly consumed food group in the past 24-hours by female adolescents in the study area was starchy staple (82.2%) and the least consumed food group was flesh meat and fish (3.3%) (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Proportion of Female Adolescents Who Consumed Different Food Groups in the Last 24 Hours Preceding the Date of Survey in Ambo Town, West Shewa, 2018 (n=523) |

Food Frequency Patterns of Female Adolescents

Of all participants, 425 (81.3%) reported that they had a habit of consuming tea and/or coffee within 30 minutes after a meal, while only 18.7% did not. Milk and milk product was the most frequently consumed food group, as 47.2% of the female adolescents consumed it ≥3 times per week. Vegetables and Eggs were consumed ≥3 times per week by 43% and 28% of female adolescents, respectively. Fish was the least frequently consumed food item, since 97.8% of the study participants reported that they never consumed it, and only 0.2% of females consumed it ≥3 times per week. Fruits, cereals, and meat were consumed by 92.2%, 91.6%, and 86.9% of the study participants 1–2 times per week, respectively (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Food frequency patterns in the last 1 week prior to the date of survey among female adolescents in Ambo town, west Shewa, Ethiopia, 2018 (n=523). |

Prevalence of Anemia

The prevalence of anemia was 39% (95% CI=34.8–43%), of which 61 (11.7%), 128 (24.5%), and 15 (2.9%) were mild, moderate, and severe anemia, respectively (Figure 2). Anemia was higher among female adolescents in the age group of 15–19 years, 139 (43%) than in those aged 10–14 years, 65 (32.5%). It was also higher among female adolescents whose menses had already started, 151 (44.7%) than who had not, 53(28.6%).

|

Figure 2 Prevalence and severity of anemia among female adolescents in Ambo town, west Shewa, Ethiopia, 2018 (n=523). |

Factors Associated with Anemia

In bivariate logistic regression, female adolescent’s age, family size, menses status, mother’s educational status, tea/coffee consumption within 30 minutes after meal, and wasting/thinness were significantly associated with anemia.

After adjusting for potential confounders, in the multivariate logistic regression, mother’s educational status, menses status of female adolescents, wasting in female adolescents, and tea/coffee consumption within 30 minutes after meal were factors that remained significantly associated with anemia.

Female adolescents who already attained menses (AOR=1.93; 95% CI=1.19– 3.13), female adolescents born to mothers who were unable to read and write (AOR=3.27; 95% CI=1.79–5.97), who always consumed tea/coffee within 30 minutes after meal (AOR=6.19; 95% CI=3.32–11.48) and who were wasted (thin) (AOR=1.67; 95% CI=1.11– 2.52) were more likely to be anemic compared to their counterparts (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study we assessed the prevalence of anemia among female adolescents in Ambo town, West Shewa, Ethiopia. We found that nearly four in ten female adolescents were anemic. Adolescents born to mothers who were unable to read and write, who always consumed tea/coffee within 30 minutes after a meal, who had already attained menses, and who were wasted (thin) were more likely to be anemic than their counterparts.

The prevalence of anemia in this study was higher than a national survey9 and other Ethiopian studies.10–12,20,21 This might be attributed to differences in the study settings, geography, and wider participants’ age group as we included adolescents of 10–19 years. The current study was community based, included both in school and out of school adolescents, and was done in an urban area. Variations in the sample size and the study period might have also contributed to producing a different estimate. The prevalence of anemia is relatively lower than similar studies from India6,22–25 which might be due to differences in socio-demographic characteristics, culture, and adolescents’ behavioral and feeding habits or practices.

We found that female adolescents who already attained menses were more likely to be anemic, which is also similar to another study.12 This might be supported by the fact that physical and physiological changes put a higher demand on female adolescents.4,26 In addition, the risk of anemia was higher among female adolescents whose mothers were not able to read and write as compared to their counterparts, which is also similar to another study.4 This could be because a mother who is educated is more likely to practice appropriate feeding to her family, since mostly a family’s foods are prepared or managed by the mothers in Ethiopia.

Female adolescents who always consumed tea/coffee within 30 minutes after a meal were more likely to be anemic. The possible justification is that post-meal consumption of tea and coffee interferes with iron absorption and inhibits the bioavailability of iron.27–30 But, it has not shown a significant association with anemia among female adolescents in other studies.8,11 Furthermore, female adolescents who were wasted (thin) were more likely to be anemic than those who were not. Literature has also witnessed that wasting is associated with anemia in female adolescents.8,11 Although some literature indicated that dietary diversity is an important contributing factor to anemia in adolescents,21,31 it was not significantly associated in this study. But, we found anemia was high among female adolescents with high DDS. Similar to the current study finding, DDS has not shown a significant association with female adolescent anemia in some other studies.11–13

The strengths of this study are; its being community-based for ease of generalizability and the use of standard procedures for anthropometry and hemoglobin measurements. But, since data were collected through recall of the past one week and 24 hours history for dietary diversity, feeding habit, and menses, this might have introduced recall bias. Another limitation is that, although malaria and sickle-cell disease are important contributors to anemia, these were not collected in our study. Given that sickle-cell disease is a rare event, and the study area is not malaria endemic, we believe that not screening these will not introduce bias in the study. Additionally, the study could not establish a temporal relationship between anemia and the independent variables since it was cross-sectional.

Conclusion

Nearly four in ten female adolescents in the study setting were anemic. Thus, anemia among female adolescents was a moderate public health problem. Adolescents born to mothers who have no formal education, who consumed tea/coffee within 30 minutes after a meal, who were wasted, and who had already attained menses should be prioritized for interventions aiming at addressing iron-deficiency anemia in female adolescents.

Data Sharing Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed for this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical Approval

An ethical approval was obtained from Institutional Health Research Ethics Review Committee (IHRERC) of Haramaya University, College of Health and Medical Sciences (Ref. No. IHRERC/197/2018). An official letter of support was sent to Ambo town health office and to other concerned bodies. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent

For females aged 10–17 years, their parents/guardians gave their informed, voluntary, written, and signed consent allowing their daughter to be part of the study, and for those ≥18 years old, the female adolescents themselves signed written, informed, voluntary consent forms. Confidentiality of the collected data was ensured through anonymity. In addition, they were informed that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

Acknowledgments

Our appreciation goes to Ambo town health office, health extension workers, and selected kebele administrators for facilitating the process of data collection. We are also thankful to the study participants, data collectors, and supervisors.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

1. WHO. The Global Prevalence of Anaemia in 2011. 2015.

2. Aguayo VM, Paintal K, Singh G. The adolescent girls’ anaemia control programme: a decade of programming experience to break the inter-generational cycle of malnutrition in India. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(9):1667–1676. doi:10.1017/S1368980012005587

3. WHO. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity.vitamin and mineral nutrition information system. Geneva, Switzerland: NMH/NHD/MNM/11.1; 2011. Available from: http://www. who.int/entity/vmnis/indicators/haemoglobin. Date accessed: 21 March, 2018.

4. Pattnaik S, Patnaik L, Kumar A, Sahu T. Prevalence of anemia among adolescent girls in a rural area of Odisha and its epidemiological correlates. Indian J Matern Child Health. 2013;15(1):5.

5. WHO. Nutrition in Adolescence: Issues and Challenges for the Health Sector: Issues in Adolescent Health and Development. 2005.

6. Mallikarjuna M, Geetha H. Prevalence and factors influencing anemia among adolescent girls: a community based study. Int J Sci Res. 2015;4(5):1032–1034.

7. CSA-Ethiopia. The 2007 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia. Statistical Summary Report at National Level. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Central Statistical Agency; 2008.

8. Tesfaye M, Yemane T, Adisu W, Asres Y, Gedefaw L. Anemia and iron deficiency among school adolescents: burden, severity, and determinant factors in southwest Ethiopia. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2015;6:189.

9. CSA-Ethiopia I. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia and ICF International Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton; 2012.

10. Adem OS, Tadsse K, Gebremedhin A. Iron deficiency anemia is moderate public health problem among school going adolescent girls in Berahle district, afar, Northeast Ethiopia. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2015;3:10–16.

11. Mengistu G, Azage M, Gutema H. Iron deficiency anemia among in-school adolescent girls in rural area of bahir dar city administration, North West Ethiopia. Anemia. 2019;2019:1–8. doi:10.1155/2019/1097547

12. Regasa RT, Haidar JA. Anemia and its determinant of in-school adolescent girls from rural Ethiopia: a school based cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health. 2019;19(1):98. doi:10.1186/s12905-019-0791-5

13. Gebreyesus SH, Endris BS, Beyene GT, Farah AM, Elias F, Bekele HN. Anaemia among adolescent girls in three districts in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):92. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-6422-0

14. Nelima D. Prevalence and determinants of anaemia among adolescent girls in secondary schools in Yala division Siaya District, Kenya. Univers J Food Nutr Sci. 2015;3(1):1–9. doi:10.13189/ujfns.2015.030101

15. CSA-Ethiopia I. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016: Key Indicators Report. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF; 2016.

16. Teji K, Dessie Y, Assebe T, Abdo M. Anaemia and nutritional status of adolescent girls in Babile District, Eastern Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;24(1).

17. WHO. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1995;854(9).

18. De Onis M, Habicht J-P. Anthropometric reference data for international use: recommendations from a World Health Organization expert committee. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64(4):650–658. doi:10.1093/ajcn/64.4.650

19. Kennedy G, Ballard T, Dop M. Guidelines for Measuring Individual and Household Dietary Diversity. Rome: Nutrition and Consumer Protection Division, FAO; 2011.

20. Demelash S, Murutse M. Prevalence of anemia and its associated factors among school adolescent girls Addis Ababa, 2015. EC Nutr. 2019;14:01–11.

21. Gonete KA, Tariku A, Wami SD, Derso T. Prevalence and associated factors of anemia among adolescent girls attending high schools in Dembia District, Northwest Ethiopia, 2017. Arch Public Health. 2018;76(1):79. doi:10.1186/s13690-018-0324-y

22. Koushik NK, Bollu M, Ramarao NV, Nirojini PS, Nadendla RR. Prevalence of anaemia among the adolescent girls: a three months cross-sectional study. World J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;3(12):827–836.

23. Srinivas V, Mankeshwar R. Prevalence and determinants of nutritional anemia in an urban area among unmarried adolescent girls: a community-based cross-sectional study. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2015;5(4):283. doi:10.4103/2230-8598.165950

24. Devi S, Deswal V, Verma R. Prevalence of anemia among adolescent girls: a school based study. Int J Basic App Med Res. 2015;5(1):95–98.

25. Premalatha T, Valarmathi S, Srijayanth P, Sundar J, Kalpana S. Prevalence of anemia and its associated factors among adolescent school girls in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. Epidemiology. 2012;2(118):1165–2161.

26. Giuseppina D. Nutrition in adolescence. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21(1):32–33. doi:10.1542/pir.21-1-32

27. Nelson M, Poulter J. Impact of tea drinking on iron status in the UK: a review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2004;17(1):43–54. doi:10.1046/j.1365-277X.2003.00497.x

28. Disler P, Lynch S, Charlton R, et al. The effect of tea on iron absorption. Gut. 1975;16(3):193–200. doi:10.1136/gut.16.3.193

29. Fan FS. Iron deficiency anemia due to excessive green tea drinking. Clin Case Rep. 2016;4(11):1053. doi:10.1002/ccr3.707

30. Kumera G, Haile K, Abebe N, Marie T, Eshete T. Anemia and its association with coffee consumption and hookworm infection among pregnant women attending antenatal care at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2018;13(11). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0206880

31. Olumakaiye MF. Adolescent girls with low dietary diversity score are predisposed to iron deficiency in southwestern Nigeria. Infant Child Adolesc Nutr. 2013;5(2):85–91.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.