Back to Journals » International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease » Volume 11 » Issue 1

Prevalence of airflow limitation in subjects undergoing comprehensive health examination in Japan: Survey of Chronic Obstructive pulmonary disease Patients Epidemiology in Japan

Authors Omori H , Kaise T , Suzuki T , Hagan G

Received 5 November 2015

Accepted for publication 11 February 2016

Published 22 April 2016 Volume 2016:11(1) Pages 873—880

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S99935

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Richard Russell

Hisamitsu Omori,1 Toshihiko Kaise,2 Takeo Suzuki,2 Gerry Hagan3

1Department of Biomedical Laboratory Sciences, Faculty of Life Sciences, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, 2Development and Medical Affairs Division, GlaxoSmithKline, Tokyo, Japan; 3Independent Consultant, Marbella, Spain

Purpose: There are still evidence gaps on the prevalence of airflow limitation in Japan. The purpose of this survey was to estimate the prevalence of airflow limitation among healthy subjects in Japan and to show what proportion of subjects with airflow limitation had been diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Subjects and methods: This was an observational, cross-sectional survey targeting multiple regions of Japan. Subjects aged 40 years or above who were undergoing comprehensive health examination were recruited from 14 centers in Japan. Airflow limitation was defined as having forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity less than 70%.

Results: In a total of 22,293 subjects, airflow limitation was most prevalent in subjects aged over 60 years (8.7%), but was also observed in subjects aged 50–59 years (3.1%) and 40–49 years (1.7%). Overall prevalence was 4.3%. Among subjects with smoking history (n=10,981), the prevalence of airflow limitation in each age group (12.8% in those aged over 60 years, 4.4% in those aged 50–59 years, and 2.2% in those aged 40–49 years) and overall prevalence (6.1%) were higher than that of total subjects. Of the smokers with airflow limitation, 9.4% had been diagnosed with COPD/emphysema and 27.3% with other respiratory diseases.

Conclusion: Among smokers undergoing comprehensive health examination, prevalence of airflow limitation reached 12.8% in those aged over 60 years and airflow limitation was observed in subjects aged 40–59 years as well, though their prevalence was lower than that in subjects aged over 60 years. We demonstrated that a significant proportion of smokers with airflow limitation had not been diagnosed with COPD/emphysema, suggesting that some of them can be diagnosed with COPD or other respiratory diseases by a detailed examination after comprehensive health examination. Screening for subjects at risk of COPD by spirometry in comprehensive health examination starting at 40 years of age, followed by a detailed examination, may be an effective approach to increase the diagnosis of COPD.

Keywords: spirometry, lung function, screening, smoking, general population

Introduction

The disease burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is increasing worldwide with the aging of the population and patterns of exposure to risk factors, which is of major economic concern.1,2 COPD is predominantly caused by smoking, but other factors, particularly occupational exposures, may also contribute to the development of COPD. It is preventable and treatable; therefore, the importance of early detection and treatment has been emphasized.3

Many rigorous epidemiological studies have been conducted to determine the prevalence of COPD globally.4–6 In Japan, several surveys to estimate the prevalence of airflow limitation have been done, though only spirometry testing without reversibility testing was performed in these surveys. A large-scale epidemiological survey was performed in the year 2000 which reported that 10.9% of subjects aged 40 years or above exhibited airflow limitation and at least 8.6% were thought to have COPD if potential asthma patients were excluded.7 Among the subjects with airflow limitation, only 9.4% reported a previous diagnosis of COPD. Another study showed that the prevalence of airflow limitation among subjects undergoing comprehensive health examination aged 40–69 years in Japan was 7.0%.8 Minakata et al9 reported that the prevalence of airflow limitation among outpatients aged 40 years or above who visited primary care clinics in Japan was 11.2%, including 10.3% of COPD if potential asthma patients were excluded. The most recent large-scale survey to estimate the prevalence of airflow limitation in Japan was done in 20048 and there is only limited information on the current situation.

In primary care clinics in Japan, spirometry is not used frequently, which may be leading to an underdiagnosis of airflow limitation.10 However, comprehensive health examination in Japan has spirometry testing as a required item,8,11 and this setting can, therefore, be used to collect spirometry data in a systematic way along with other clinical characteristics among healthy subjects. There are two types of annual health examinations in Japan, “comprehensive health examination” and “general health examination”, targeting healthy subjects, in order to detect potential health risks at an early stage. General health examination is legally required for employees to undergo annually, while comprehensive health examination is for people to participate voluntarily and covers broader range of test items including spirometry testing.

The aim of this survey (Survey of Chronic Obstructive pulmonary disease Patients Epidemiology in Japan [SCOPE-J]) was to estimate the prevalence of airflow limitation on a large scale with over 20,000 subjects undergoing comprehensive health examination in multiple regions of Japan. Since spirometry in comprehensive health examination without reversibility testing is not for definitive diagnosis of COPD but for screening subjects at risk of COPD, subjects found to have airflow limitation include patients with asthma or other respiratory diseases as well as COPD. However, spirometry in comprehensive health examination may still have the merit to provide good estimate for the prevalence of airflow limitation in a large-scale population. Also, it may be informative to show what proportion of subjects with airflow limitation has been diagnosed with COPD, in order to know whether significant number of COPD patients remain undiagnosed. In our survey, subjects were asked to complete the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) questionnaire,12 not for diagnosing COPD but for evaluating the presence of respiratory symptoms of cough, sputum, and breathlessness, by referring to responses in the CAT questionnaire. CAT was originally developed with the aim of developing better understanding among both COPD patients and physicians in daily clinical practice on how the condition of the disease was affecting health and daily living of the patients. Additionally, for research purposes, CAT has also been used in evaluating the respiratory symptoms of a wider population including healthy subjects13 and non-COPD patients.14

Subjects and methods

Study design and participants

This was a cross-sectional observational survey conducted in 14 centers in Japan. Subjects were recruited between December 2012 and August 2013. The target number of subjects was set at 20,000 considering the estimated prevalence of airflow limitation among healthy subjects to be 7%.8 The survey population included male and female subjects aged 40 years or above who underwent comprehensive health examination in one of the 14 institutions located in Kanto, Chubu, Kinki, Chugoku, Shikoku, and Kyushu regions in Japan. Subjects were asked to volunteer for this survey, regardless of their smoking history, current respiratory symptoms, or history of respiratory diseases. Subjects who agreed to participate were included in this survey after obtaining their written informed consent. This survey was conducted according to the Helsinki Declaration in compliance with the “Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Research” (dated December 1, 2008). The initial overall ethics approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee at the Kumamoto University.

Procedures

Spirometry was performed in each subject as a required item in the comprehensive health examination. Reversibility testing using a bronchodilator was not performed as it was deemed unacceptable by the Ethical Review Committee to perform in subjects who were attending for a routine health examination and not for diagnosis of COPD. The spirometer quality control and calibration were performed according to the current recommendations.15 All the facilities for this survey belonged to Japan Society of Ningen Dock (Japanese language which refers to comprehensive health examination) which provided us with standard and high quality of spirometry testing.

Airflow limitation was defined as having forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) less than 70%. The severity of airflow limitation was evaluated on a four-grade scale as follows: Stage I (mild): % predicted FEV1 ≥80%; Stage II (moderate): % predicted FEV1 ≥50%–80%; Stage III (severe): % predicted FEV1 ≥30%–50%; and Stage IV (very severe): % predicted FEV1 <30%. The expected FEV1 was calculated with the formula specified by the Japanese Respiratory Society (male: FEV1 [L] =0.036× body height [cm] −0.028× age−1.178; female: FEV1 [L] =0.022× body height [cm]−0.022 × age−0.005).16

In addition to spirometry, the following data were recorded: age, sex, height, body weight, body mass index, smoking history, histories of respiratory diseases, and CAT. History of disease included past diagnosis and current treatment. Among the subjects, current smokers and past smokers were classified as “smokers”, regardless of pack-years in this survey.

Statistical analysis

All data were processed and summarized by the use of Statistical Analysis System version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

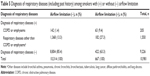

A total of 22,293 subjects (14,013 [63%] males and 8,280 [37%] females) were enrolled in this survey (Table 1). The mean age (±standard deviation) of the subjects was 54.7 (±9.6) years. A total of 26.8% of the males and 6.7% of the females were current smokers, while 42.0% of the males and 10.2% of the females were past smokers.

| Table 1 Characteristics of the subjects enrolled in the survey |

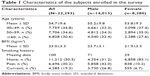

Table 2 shows the age distribution by the sex of survey subjects and the Japanese general population. Both males and females in this survey were younger, compared to the Japanese general population. The proportion of males in this survey (62.9%) was higher than that of general population (46.9%).

| Table 2 Comparison of age distribution by sex between the survey subjects and Japanese general population |

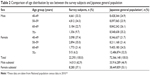

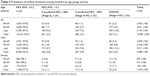

Of the total 22,293 subjects, airflow limitation was most prevalent in subjects aged over 60 years (8.7%), but was also observed in subjects aged 50–59 years (3.1%) and 40–49 years (1.7%). Airflow limitation was more prevalent among males than among females in each age group. Overall prevalence was 4.3% (Table 3). Among 529 subjects with airflow limitation who had a % predicted FEV1 <80% (at Stage II, III, or IV), most of the subjects were at Stage II (n=481) compared to Stage III (n=46) and IV (n=2). Among subjects with smoking history (n=10,981), airflow limitation was most prevalent in subjects aged over 60 years (12.8%), but was also observed in subjects aged 50–59 years (4.4%) and 40–49 years (2.2%). Airflow limitation was more prevalent among males than among females in each age group among smokers as well. Overall prevalence was 6.1% (Table 4). Age–sex-specific and overall prevalence of airflow limitation among the smokers was higher than that of the total subjects. The majority of the smokers with airflow limitation who had a % predicted FEV1 <80% (n=386) were at Stage II (n=347), compared with Stage III (n=39), and no smokers were at Stage IV. Among the smokers in this survey, 93.4% of subjects with airflow limitation and 91.8% of subjects without airflow limitation reported on the CAT score that they had at least one of the respiratory symptoms of cough, sputum, and breathlessness.

| Table 3 Prevalence of airflow limitation among total subjects by age group and sex |

| Table 4 Prevalence of airflow limitation among smokers by age group and sex |

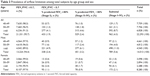

Among the smokers with airflow limitation, only 9.4% (n=63/667) had been previously diagnosed with COPD or emphysema (Table 5). Also, 27.3% of the smokers had been diagnosed with respiratory diseases other than COPD/emphysema, which included bronchial asthma, pneumonia, and chronic bronchitis. On the other hand, among the smokers without airflow limitation, 1.4% had been diagnosed with COPD/emphysema and 13.3% had been diagnosed with other respiratory diseases.

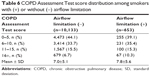

The proportion of subjects who reported CAT scores of 11 or higher among smokers with airflow limitation (25.6%) was higher than that among smokers without airflow limitation (22.2%); however, the distribution of CAT scores in the two groups was not much different (Table 6).

| Table 6 COPD Assessment Test score distribution among smokers with (+) or without (-) airflow limitation |

Discussion

This large-scale cross-sectional Japanese survey estimated the prevalence of airflow limitation among subjects aged 40 years or above who were undergoing comprehensive health examination. The prevalence in people aged over 60 years reached 8.7% of the total subjects and 12.8% among smokers, and airflow limitation was observed in 40s and 50s as well, though their prevalences were lower than that of people aged over 60 years. The prevalence of airflow limitation was estimated in various settings in previous studies conducted in Japan. Fukuchi et al7 recruited subjects from the general population by randomly contacting them by telephone and inviting them to attend the clinics for spirometry testing; Minakata et al9 recruited patients who visited primary care clinics to treat diseases other than respiratory diseases; and Omori et al8 approached subjects undergoing comprehensive health examination. Since comprehensive health examination provides us with a good opportunity to collect spirometry data in a systematic way from healthy subjects, we have also approached this setting in this survey. Subjects undergoing comprehensive health examination are mostly company employees with the financial support of companies and partly nonemployee community residents, including elderly people, with the financial support of municipalities, and thus, age and sex distribution of the subjects is skewed toward younger ages and men, compared to the general population (Table 2). Since the prevalence of airflow limitation was higher in the older age group and among men as shown in previous studies,7,8 we need to interpret the overall prevalence of airflow limitation in this survey by considering age and sex distribution attributable to the setting of comprehensive health examination. Even with the skewed age and sex distribution, comprehensive health examination is a unique setting that enables us to collect spirometry data routinely from subjects, regardless of existence of respiratory symptoms, and may be a good opportunity to screen subjects at risk of COPD. The present study demonstrated that 9.4% of the smokers with airflow limitation had been diagnosed with COPD/emphysema and 27.3% of them had been diagnosed with other respiratory diseases. Remaining 63.3% had not been diagnosed with any respiratory diseases, but some of them could be found to have any respiratory diseases (including COPD and asthma), if they had further detailed examination to receive a definitive diagnosis. Also, among 27.3% of them who had been diagnosed with respiratory diseases other than COPD/emphysema, some patients could be found to have comorbid COPD/emphysema after detailed examination, since asthma and COPD can coexist. It is known that untreated COPD can result in substantial loss of functional status in affected patients and can also contribute to increased costs of care by delaying treatment until the disease becomes more advanced and by missing the opportunity to reduce the risk of costly exacerbations.17 Early diagnosis promotes early intervention before the burden of COPD on the society becomes more substantial. Recent publications demonstrate that earlier intervention could reduce the decline in FEV1.18 Conclusively, earlier diagnosis and intervention could improve the prognosis of COPD for individual patients and reduce the disease burden of COPD on the society.

Past surveys to estimate the prevalence of airflow limitation in Japan approached healthy subjects or outpatients aged 40 years or above and found airflow limitation in people in their 40s, though the prevalence was lower than in older age groups.7–9,14 This survey also targeted subjects aged 40 years or above. Since earlier diagnosis is a key for reducing the disease burden of COPD, the prevalence data in 40s could be informative. Spirometry without reversibility testing could include overestimated cases of true airflow limitation due to confounding factors such as common cold, recent history of occupational exposure, or air pollution, but the risk for overestimation of true airflow limitation could be applicable to all age groups.

Under-recognition may contribute to underdiagnosis of COPD. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Japanese Committee demonstrated that the awareness of COPD by the public increased from 17.1% in 2009 to 30.5% in 2013 by approaching 5,000 men and 5,000 women aged between 20s and 60s by random selection from the panel and examining the number of survey participants who had knowledge about COPD or who knew the name COPD.19 Our results suggest that early diagnosis of COPD is still challenging, even with the partial increase in the awareness of COPD. The awareness may need to be further increased in order to promote early diagnosis of COPD.

It was reported that the proportion of subjects who had a further medical consultation based on the results of comprehensive health examination varied depending on the examination items.20 The proportion was relatively high for some examination items (92.6% for pancreas echo pattern, 80.6% for renal function, and 76.3% for heart function), while it was relatively low for those of lifestyle-related diseases, including blood pressure (44.8%), blood lipids (47.6%), and glycometabolism (58.1%). The proportion for spirometry went down as low as 38.3%. Thus, subjects identified as having abnormal spirometry results in comprehensive health examination may need to be proactively encouraged to have medical consultation for further examination leading to early diagnosis of COPD.

Presence of respiratory symptoms was explored by evaluation of responses to the CAT in this survey, and 93.4% of smokers with airflow limitation and 91.8% of smokers without airflow limitation had at least one of the respiratory symptoms of cough, sputum, and breathlessness. However, only 6.1% of the smokers had already developed airflow limitation. Distribution of CAT total score of smokers with airflow limitation overlapped very much with that of smokers without airflow limitation. These results suggest that CAT cannot be used to screen for COPD and spirometry is essential to make the diagnosis.

Cigarette smoking is well known as a major cause of COPD, with a higher prevalence of COPD reported among people with a high smoking index.21,22 In another study conducted in Japan, it was shown that cigarette smoking increases the risk of airflow limitation in a healthy Japanese population.23 In our survey, the overall prevalence of airflow limitation in smokers was 6.1%. It was particularly high in subjects aged over 60 years (12.8%), but we identified 4.4% of subjects aged 50–59 years and 2.2% of subjects aged 40–49 years with airflow limitation. Although the smoking rate among Japanese males is gradually decreasing, it is still higher than that in Western countries.24,25 Recently, there has been some concern that the prevalence of COPD will increase among Japanese females, because the smoking rate has increased during a certain period in the younger-generation females.24,25 Smokers are at risk of COPD and may need to have periodic COPD screening by spirometry followed by medical consultation if abnormal spirometry results are found.

The strength of this survey is estimating the prevalence of airflow limitation and the proportion of undiagnosed subjects with COPD by conducting a large-scale survey targeting multiple regions in Japan. All the facilities in this survey belong to Japan Society of Ningen Dock (Japanese language which refers to comprehensive health examination) which provided standardized and high quality of spirometry testing. One of the limitations of this survey is that age and sex distribution of subjects differs from that of general population because of the setting of comprehensive health examination, and the survey results need to be interpreted by considering this point. Another limitation is that spirometry in comprehensive health examination without reversibility testing is not used for definitive diagnosis of COPD, but for screening subjects at risk of COPD, and thus, subjects found to have airflow limitation include patients with asthma or other respiratory diseases as well as COPD. Detailed examination after comprehensive health examinations is needed for definitive diagnosis of COPD by performing reversibility testing, collecting information on symptoms, and giving differential diagnoses of other respiratory diseases. Even with this limitation, spirometry in comprehensive health examinations may have the merit to provide good estimate for the prevalence of airflow limitation in a large-scale population.

Conclusion

Among smokers undergoing comprehensive health examination, prevalence of airflow limitation reached 12.8% in those aged over 60 years and airflow limitation was observed in those in their 40s and 50s as well, though their prevalence was lower than that of those over 60. We demonstrated that significant proportion of smokers with airflow limitation had not been diagnosed with COPD/emphysema, suggesting that some of them can be diagnosed with COPD or other respiratory diseases by detailed examination after comprehensive health examination. Screening for subjects at risk of COPD by spirometry in comprehensive health examination starting at age 40, followed by the detailed examination may be an effective approach to increase the diagnosis of COPD.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the people who participated in this survey and the staff in the medical institutions who contributed to this survey. The following investigators took part in data collection of this survey: Dr Takeshi Nawa (Hitachi General Hospital, Hitachi Ltd.), Dr Kazuhiro Gotou (Health Park Clinic Kurosawa), Dr Takashi Nakagawa (Omiya City Clinic), Dr Koji Yamashita (Yotsukaido Tokushukai Hospital), Dr Tatsuo Morikawa (Tokyo-Nishi Tokushukai Hospital), Dr Takayuki Kashiwabara (JA Shizuoka Kohseiren Enshu Hospital), Dr Tatsuya Shiraki (Matsubara Tokushukai Hospital), Dr Ryo Kobayashi (Bell Clinic), Dr Hiroshi Sonobe (Chugoku Central Hospital), Dr Toshiki Fukui (Center for Preventive Medical Treatment, NTT West Takamatsu Hospital), Dr Tokuji Motoki (Kochi Kenshin Clinic), Dr Yasuhiro Ogata, Dr Noritaka Higashi (Japanese Red Cross Kumamoto Healthcare Center), Dr Junko Aburaya (Koga Kenshin Center, Koga Ekimae Clinic), and Dr Koki Ido (Osumi Kanoya Hospital).

Editorial support in the form of development of the initial draft, collating author comments, editorial suggestions to draft versions of this paper, assembling tables and figures, copyediting, and referencing was provided by Diana Jones of Cambrian Clinical Associates Ltd. (Cardiff, UK) and was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

Author contributions

All authors participated in the design and interpretation of this survey and the development of this manuscript. All authors had full access to the data and gave final approval before submission.

Disclosure

GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) was the funding source and was involved in all stages of the conduct of this survey (WEUSKOP6290). GSK also funded all costs associated with the development and publishing of the present manuscript. The institution Hisamitsu Omori belongs to received funding for this survey from GSK, and he received lecture fees from GSK outside of this survey. Toshihiko Kaise is an employee of GSK and owns stock of the company. Takeo Suzuki is an employee of GSK. Gerry Hagan has received consultancy fee and travel assistance from GSK and reports ownership of GSK shares; has received consultancy fee from Almirall, Bayer, Merck, Mundipharma, Novartis, and Nycomed; and previously worked for GSK. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Feenstra TL, van Genugten MLL, Hoogenveen RT, et al. The impact of aging and smoking on the future burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:590–596. | ||

Global Initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease 2013. Available from: www.goldcopd.com. Accessed March 12, 2015. | ||

Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:532–555. | ||

Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population based prevalence study. Lancet. 2007;370:741–750. | ||

Menezes AM, Perez-Padilla R, Jardim JR, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five Latin American cities (the PLATINO study): a prevalence study. Lancet. 2005;366:1875–1881. | ||

Halbert RJ, Natoli JL, Gano A, Badamgarav E, Buist AS, Mannino DM. Global burden of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:523–532. | ||

Fukuchi Y, Nishimura M, Ichinose M, et al. COPD in Japan: the Nippon COPD Epidemiology study. Respirology. 2004;9:458–465. | ||

Omori H, Nonami Y, Mihara S, Marubayashi T, Morimoto Y, Aizawa H. Prevalence of airflow limitation on medical check-up in Japanese subjects. J UOEH. 2007;29:209–219. | ||

Minakata Y, Sugiura H, Yamagata T, et al. Prevalence of COPD in primary care clinics: correlation with non-respiratory diseases. Intern Med. 2008;47:77–82. | ||

Takahashi T, Ichinose M, Inoue H, Shirato K, Hattori T, Takishima T. Underdiagnosis and undertreatment of COPD in primary care settings. Respirology. 2003;8:504–508. | ||

Oike T, Senjyu H, Higa N, et al. Detection of airflow limitation using the 11-Q and pulmonary function tests. Intern Med. 2013;52:887–893. | ||

Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, Wiklund I, Chen WH, Kline Leidy N. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:648–654. | ||

Nishimura K, Mitsuma S, Kobayashi A, et al. COPD and disease-specific health status in a working population. Respir Res. 2013;14:61–67. | ||

Onishi K, Yoshimoto D, Hagan GW, Jones PW. Prevalence of airflow limitation in outpatients with cardiovascular diseases in Japan. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:563–568. | ||

Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–338. | ||

The Japanese Respiratory Society. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of COPD. 3rd ed. Tokyo; 2009. | ||

Price D, Freeman D, Cleland J, Kaplan A, Cerasoli F. Earlier diagnosis and earlier treatment of COPD in primary care. Prim Care Respir J. 2011;20:15–22. | ||

Decramer M, Celli B, Kesten S, et al. Effect of tiotropium on outcomes in patients with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (UPLIFT): a prespecified subgroup analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1171–1178. | ||

GOLD Japanese Committee. Survey on the awareness of COPD. Available from: http://www.gold-jac.jp/copd_facts_in_japan/copd_degree_of_recognition.html. Accessed August 17, 2015. | ||

Wada T, Terashima S, Mimua A, et al. Effectiveness of encouragement to receive further consultation 3 month after Ningen Dock and future problems. Ningen Dock. 2012;27:748–754. | ||

Miravitlles M, Soriano JB, Garcia-Rio F, et al. Prevalence of COPD in Spain: impact of undiagnosed COPD on quality of life and daily life activities. Thorax. 2009;64:863–868. | ||

Zhong N, Wang C, Yao W, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a large, population-based survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:753–760. | ||

Osaka D, Shibata Y, Abe S, et al. Relationship between habit of cigarette smoking and airflow limitation in healthy Japanese individuals: the Takahata Study. Inter Med. 2010;49:1489–1499. | ||

Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare. Measures for National Health Promotion. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/wp/wp-hw2/part2/p3_0024.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2015. | ||

World Health Organization Regional Office for Western Pacific; 2002. Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs_20020528/en/. Accessed March 12, 2015. | ||

National population census data in 2010. Available from: http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/List.do?bid=000001034991&cycode=0. Accessed March 12, 2015. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.