Back to Journals » Infection and Drug Resistance » Volume 14

Prevalence and Genotype Distribution of Human Papillomavirus Among Healthy Females in Beijing, China, 2016–2019

Authors Yu H , Yi J, Dou YL, Chen Y, Kong LJ, Wu J

Received 6 August 2021

Accepted for publication 30 September 2021

Published 10 October 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 4173—4182

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S332668

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Suresh Antony

Hao Yu,1,2 Jie Yi,1 Ya-ling Dou,1 Yu Chen,1 Ling-jun Kong,1 Jie Wu1

1Department of Laboratory Medicine, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Science & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Laboratory Medicine, Beijing Hepingli Hospital, Beijing, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Jie Wu

Department of Laboratory Medicine, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, No. 1 Shuaifuyuan Wangfujing, Dongcheng District, Beijing, 100730, People’s Republic of China

Tel +86 106 915 9701

Email [email protected]

Objective: Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, especially with high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) genotypes, is closely associated with cervical cancer. This study aimed to observe the epidemiological characteristics of HPV infection among healthy women in Beijing, China.

Materials and Methods: Cervical specimens were collected from 29,436 healthy women, who underwent health check-ups in Peking Union Medical College Hospital between 2016 and 2019. A commercial kit was used for the detection of 15 HR-HPV and two low-risk HPV (LR-HPV) genotypes.

Results: A total of 3586 (12.18%) participants tested positive for HPV, 3467 of which were infected with HR-HPVs. The most prevalent genotypes were HPV52, 58, 16, 51, and 56. Moreover, while infection with a single genotype (9.84%) was more prevalent, HPV16+52 was the most common combination in those infected with multiple HPVs. Furthermore, the highest infection rate among age groups was in women aged < 25 years (20.92%). No significant difference in the prevalence was observed from 2016 to 2019. However, HPV incidence in Beijing was significantly different than that in all other areas in China, except for Zhengzhou (p < 0.05).

Conclusion: Our findings could serve as potential reference for better understanding of the epidemiological characteristics of HPV infection in Beijing.

Keywords: human papillomavirus, cervical cancer, prevalence, genotype

Introduction

Cervical cancer is one of the most common malignancies in women. In 2018, it was ranked fourth in terms of incidence and mortality in females.1 Globally, roughly 570,000 new cases and 311,000 deaths worldwide were associated with this disease in 2018, one-fifth of which were reported in China.2 Moreover, the global average age of women diagnosed with cervical cancer is 53 years, ranging from 44 to 68 years, and the global average age at death from cervical cancer is 59 years, ranging from 45 to 76 years.3 Hence, cervical cancer remains a major public health problem affecting females, especially those in China.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) has been detected in almost all cases of cervical cancers.4 At present, more than 100 HPV genotypes are known, and these are classified into high-risk HPV (HR-HPV), intermediate risk HPV (IR-HPV) and low-risk HPV (LR-HPV), based on their ability to induce premalignant and malignant transformation.5,6 Over 100 cervical cancer genotypes have been recognized, and at least 15 of those have been classified as HR-HPV.7 Persistent infection with HR-HPV is the main risk factor of cervical cancer, whereas infection with LR-HPV is related with genital warts.8 Two HR-HPV genotypes, HPV16 and HPV18, account for roughly 70% of all cervical cancer cases.9 Other genotypes associated with cervical adenocarcinomas include HPV31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68.10

HPV vaccines have been developed as a means of preventing cervical cancer and its precancerous lesions and have been effective in preventing and controlling HPV infection in some developed countries.11–13 However, because of differences in demographic, geographic, and ethnic factors, the prevalence and genotype distribution of HPV also varies across countries and regions worldwide,14–16 and this might lead to different distribution levels of cervical cancer subtypes and precancerous cervical lesions.17,18 Hence, it is very important to fully investigate the prevalence and genotype distribution of HPV in order to develop proper monitoring, and prevention and control tactics against the virus.

In this study, data from healthy females in Beijing area were analyzed, and the prevalence and distribution of HPV were evaluated in order to provide a scientific basis for the development and evaluation of the effectiveness of HPV vaccines and HPV screening in this region.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

This was a retrospective study to determine the prevalence of HPV infection. We performed a cross-sectional analysis, wherein we collected data of 29,436 healthy females aged 18–86 years old who visited the Peking Union Medical College Hospital and received a routine medical examination between 2016 and 2019. To be included in this study, the healthy women: (1) were aged 18 years or more; (2) were a permanent resident of the local area; (3) were mentally and physically healthy; (4) were not pregnant; and (5) had not undergone a total hysterectomy or cervicectomy. All enrolled patients underwent a routine gynecological check; their cervical specimens were examined for HPV DNA genotyping.

Ethics Statement

The study adhered to strict the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (No. S-K1573). Informed consent was taken from all participants who joined the study.

Sample Collection

Sample collection was performed by a gynecologist. Cervical exfoliated cell specimens were collected using a disposable cervical brush. Thereafter, the brush was transferred to a sampling tube containing a cell preservation liquid. All the samples were stored at 4 °C and then transported to the molecular biology laboratory; subsequent tests were performed within 48 h.

HPV DNA Testing

HPV DNA was extracted using an Autrax automatic nucleic acid extraction workstation (Liferiver Biotechnology Limited Corp. Shanghai, China). HPV DNA was amplified using a Roche LightCycler 480 instrument (Roche, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. HPV genotyping was performed using two HPV genotyping kits for 17 HPV types (Liferiver Biotechnology Limited Corp. Shanghai, China), wherein one kit included nine HR-HPV types (HPV16, 18, 39, 45, 56, 59, 66, 68 and 82) and six IR-HPV types (HPV31, 33, 35, 51, 52, and 58), and another included two LR-HPV types (HPV6 and 11). These assay kits rely on a TaqMan-based real-time fluorescent quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method. The amplification procedure of the HR-HPV and IR-HPV genotyping kit was performed as follows: 2 min of denaturation at 94 °C, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 93 °C for 10 s, 31 s of annealing and elongation at 62 °C. Single-point fluorescence was detected at 62 °C. The lowest limit of detection (LOD) was 1 × 104 copies/mL. The LR-HPV genotyping kit comprised specific primers and probes designed according to the conserved regions of the HPV6 and HPV11 genomes, and was used to detect the double positive sample of HPV6 and HPV11. The amplification procedure was as follows: 2 min of pre-denaturation at 37 °C, then 2 min of denaturation at 94 °C, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 93 °C for 15 s, 60 s of annealing and elongation at 60 °C. Single-point fluorescence was detected at 62 °C. The lowest LOD was 1 × 103 copies/mL. Internal quality control and external quality assessment (negative control and positive control) were performed to ascertain the reliability of the results. Internal quality control was used to ensure that the cervical epithelial cells had been collected.

Analysis of Distribution and Prevalence

Genotypic data from 2016 to 2019 were retroactively collected from our hospital database and subsequently analyzed to perform a comparison between HPV infection prevalence in Beijing and other areas of China, for which some recently published regional studies based on a larger population sample were collected.19–30 The other regional studies were categorized into four macro-geographical regions: east (Shanghai, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Jiangxi), west (Xinjiang and Sichuan), south (Wuhan, Guangdong, and Yunnan), and north (Zhengzhou, Shaanxi, and Shandong).

Statistical Analysis

Participant age data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation. All participants were divided into 10 groups according to their age during HPV testing, with each group covering a 5-year range. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Differences between groups were compared by chi-squared test (χ2). For all statistical analyses, p-values were two-sided and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall and Type-Specific HPV Prevalence

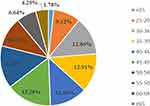

This study analyzed data of HPV tests of 29,436 healthy women collected between 2016 and 2019. The age of the women ranged from 18 to 86 years, and the mean age was 44.95 ± 11.38 years. Of the 29,436 subjects, 3586 women were positive for HPV, with an overall HPV infection rate of 12.18%. The constituent ratio of the age groups of HPV-positive patients is shown in Figure 1, which indicates that the groups with the highest percentages of healthy women were of age groups 45–49 years (15.28%, 548/3586) and 50–54 years (14.33%, 514/3586).

|

Figure 1 Constituent ratio of different age groups of HPV infection. |

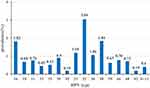

HR-HPV was detected in 3467 individuals, with an infection rate of 11.78% (3467/29,436). The most prevalent genotypes were HPV52, with a frequency of 3.04% (895/29,436), followed by HPV58, 16, 51 and 56, with frequencies of 1.84% (541/29,436), 1.82% (535/29,436), 1.18% (346/29,436) and 1.06% (311/29,436), respectively (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2 Distribution of HPV genotypes among healthy women. |

The prevalence of infection with HPV16/18, HPV6/11/16/18, and HPV16/18/52/58 was 20.8% (720/3586), 23.01% (825/3586), and 52.43% (1880/3586), respectively, in the HPV-positive patients.

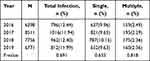

Distribution Characteristics of Single and Multiple Infections

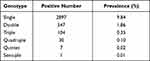

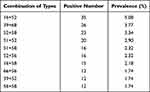

The analysis of the characteristics of HPV infections across all the samples showed that infection with single and multiple HPVs were at 9.84% (2897/29436) and 2.34% (689/29436), respectively. Among those infected with multiple HPVs, double infection was the most prevalent, and affected 547 females (Table 1). Further analysis of double infections revealed ten common combinations of HPV subtypes (Table 2), of which, HPV16+52 was the most common subtype, accounting for 5.08% (35/689) of double infections.

|

Table 1 Frequency and Prevalence of Single and Multiple HPV Infection Among Healthy Women |

|

Table 2 The Top Ten Combinations of Genotypes in HPV Double Infections |

Age-Specific Prevalence of HPV Infection

HPV prevalence in different age groups is shown in Figure 3A. The results indicate that there was a significant difference in the infection rates among the different age groups (p < 0.05). Moreover, healthy women who were younger than 25 years had the highest HPV prevalence (20.92%, 64/306), whereas healthy women who were over 65 years had the lowest prevalence (10.97%, 154/1404).

Significant differences were also found among the ten age groups in terms of single and multiple infections (p < 0.05). The trend was similar to the results presented earlier, wherein the prevalence of a single infection was much higher than that of a multiple infection, and the rate of single and multiple infections in healthy women aged less than 25 years old was significantly higher than that in other groups (p < 0.05) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3C reveals the variation tendency of the five most common HPV subtypes (HPV16, 51, 52, 56 and 58) among different age groups in healthy females. There were significant differences in the distribution of these five subtypes among the ten age groups (p < 0.05). In this study, the prevalence of HPV52 in each age group was much higher than that of the other four subtypes. Moreover, the positive rate of HPV16 was higher than that of HPV58 in all age groups, except for those aged 40–64 years.

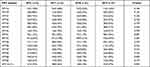

Prevalence of HPV Grouped by Year

From 2016 to 2019, the annual prevalence of HPV infection among the healthy females was not significantly different (p > 0.05). In the past 4 years, cases with a single infection were consistently higher than those with multiple infections, and this trend was similar to that of overall infection discussed earlier (Table 3). Infections with each subtype from 2016 to 2019 are summarized in Table 4, and significant differences in distribution were seen for subtypes of HPV39, 58, 59, 68, 6 and 11 during this period (p < 0.05). Differences among the annual HPV-positive rates of healthy women aged 30–34 years were significant (p < 0.05) during the study period (Table 5).

|

Table 3 Comparison of Annual Total, Single, and Multiple Infection Rates of HPV from 2016 to 2019 |

|

Table 4 Comparison the Prevalence of Different HPV Subtypes from 2016 to 2019 |

|

Table 5 Comparison of HPV Infection Rate of Different Ages from 2016 to 2019 |

Region-Specific Prevalence of HPV Infection

The prevalence of HPV infection in Beijing and in 12 different areas of China was compared separately (Table 6). The positive rate of HPV obtained in our study (Beijing) was significantly different from those in other areas (p < 0.05), except for Zhengzhou. Moreover, the highest rate of HPV infection was in Shaanxi Province (30.21%, 4263/14,111),29 whereas the lowest was in Zhengzhou City (12.09%, 6020/49,793),20 with an incidence rate similar to that observed in our study. The three most common genotypes of HPV infections, namely HPV 16, 52 and 58, were consistent among these regions, and the infection rates of these three subtypes among different regions are listed in Table 7.

|

Table 6 Comparison of HPV Infection Rates in Different Areas in China |

|

Table 7 Prevalence of the Three Most Common HPV Genotypes of in Different Areas in China |

Discussion

Our cross-sectional study evaluated the prevalence and genotype distribution of HPV in healthy women in China, with the aim of better understanding the epidemiological characteristics of HPV infection in Beijing. In this study, the prevalence of HPV infection among apparently healthy women in Beijing was 12.17%. In contrast, a recent research in Beijing has shown that 21.06% women were infected with HPV.31 The difference may have been mainly due to differences in the targeted populations screened, since the former study was based on all women who visited the hospital and received an HPV test, whereas our study was based on healthy women who received a routine medical examination.

In agreement with previous studies, we found that HPV16, 52, and 58 were the three most common subtypes in most regions in China.32,33 However, this result was distinct from that of a meta-analysis involving 1 million women from five continents, which indicated that the three most commonly identified HR-HPV genotypes worldwide were HPV16, 18, and 52.34 Although the majority of the 29,436 healthy females in this study were infected with a single HPV genotype, the possibility of multiple-type infections cannot be ignored. Multiple studies suggest that infections with multiple HPV genotypes might increase the length of persistent infection, and possibly further increase the risk of developing cervical cancer.35,36 Moreover, the three most common combinations of genotypes in multiple HPV infections were HPV16+52, HPV39+68, and HPV52+58. Interestingly, while HPV39 and 68 were not part of the three most commonly detected HPV genotypes, they were part of the common combinations of genotypes in multiple infections. This may be linked to the tendency of HPV68 infection rate to increase yearly; HPV39 infection was ranked sixth in prevalence in this study. However, this finding should be confirmed in larger cohorts.

In our study, HPV infection rates were different across different age groups, and this was also observed in previous reports.34,37 Our results showed that the prevalence of HPV significantly peaked below the age of 25 years, then showed a clearer trend of moderating in the middle age groups, and was a fluctuating variation of two little peaks after the age of 45. In terms of multiple infections, there was a gradual upward trend in the over 45 years old age groups. The higher HPV prevalence in young women might be related to more frequent sexual intercourse and inadequate awareness of safety.38,39 Moreover, they were likely more sensitive to HPV infections after the beginning of sexual behavior, as a result of immature immune protection; however, majority of infections are temporary.40 When women reach menopause, fluctuations in hormones cause a series of physiological and psychological changes, and immune dysfunction. It is possible that this places them in a more vulnerable category for HPV, owing to their diminishing ability of eliminating and inhibiting the virus.41,42 Therefore, HPV screening should be taken much more seriously for women over the age of 45. In some studies, researchers observed a bimodal curve (or an U‐shape curve) in the age‐specific HPV distribution.22,24,43 However, the phenomenon of the curve was not obvious in our study, and whether or not it exists in healthy women remains to be seen in follow-up studies.

While variations in the incidence of HPV infection were observed from 2016 to 2019, the results of this study showed no significant difference in the total, single, and multiple infections observed within four years, and suggested that the positive rate of HPV may tend to stabilize in this population. However, significant changes in the prevalence of some genotypes were observed during this period. Specifically, the prevalence of HPV58 tended to decrease, whereas that of HPV68 tended to increase and even ranked fourth in 2019. As an important part of common combinations of genotypes, it is also a noteworthy point. For future studies, we will continue to collect data, and observe the trend of positive rates of HPV and different genotypes over the years.

There is a great deal of research indicating that HPV infections are significantly region-specific.33,44,45 Compared with similar studies in other parts of China, the prevalence observed in our study was close to what has been reported in Zhengzhou, however, it was lower than that reported in the other 11 regions. While HPV16, 52 and 58 were consistently the three most frequently observed subtypes across regions, substantial differences in their prevalence in different regions were observed. This difference in the prevalence and genotype distribution of HPV might have been due to the different geographical and economic conditions, and lifestyles in the regions considered. Apart from that, the diversity in the study populations might have also contributed to the observed difference. Hence, a multicenter study should be developed to confirm the differences further.

Three types of vaccines, namely, the bivalent (HPV16/18), quadrivalent (HPV6/11/16/18), and 9-valent HPV vaccine (HPV6/11/16/18/31/33/45/52/58), have been approved by the National Medical Products Administration in China. The 9-valent HPV vaccine covers a broader swath and has a stronger protective effect against HPV. However, it has not been used extensively in mainland China, probably because it has a strict age limit that covers only young women (16–26 years old) and its price is higher than that of others. A study on patients with cervical cancer in West China found that the five most common subtypes of HPV were HPV16, 18, 58, 53, and 33.46 In our study, two of these genotypes (HPV16 and 58) also had higher prevalence in healthy women. In addition, in multiple HPV infections, HPV16+52 was the most common combination observed. Furthermore, the positive rate of HPV16/18/52/58 accounted for more than half of all HPV infections in our study. In the light of the above findings, it is necessary to make a few adjustments in the HPV genotypes being targeted by future vaccines. For example, an HPV vaccine that covers the four additional HR-HPV types (HPV16/18/52/58) should be developed and included in the approved vaccines, as this may be more conducive to the implementation of the HPV vaccination program in China.

Conclusions

In summary, this retrospective study found that the five most prevalent HPV genotypes among healthy women in Beijing were HPV52, 58, 16, 51, and 56. A significant prevalence peak of HPV appeared in younger women aged less than 25 years. Moreover, the age-specific and region-specific prevalence of HPV infection and distribution of genotypes in healthy women were also evaluated. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate HPV infection among healthy women in Beijing. Our findings can be considered as benefit for better understanding the epidemiological characteristics of HPV infection in Beijing. However, further large-scale and multicenter studies are needed to fully understand the prevalence and genotype distribution of HPV in healthy Chinese women. The limitations of the study must be acknowledged. There was a lack in analyzing the potential risk factors for HPV infection to safeguard patient privacy; the correlation between HPV genotypes and cervical cytology grade could not been elucidated. In future studies, we aim to expand the collection of sample information and analyze the correlation between cervical cytology grade and other potential risk factors such as smoking, drinking habit, education, occupation, marital status, age at sexual debut, contraceptive use, and number of sex partners in the last six months.

Funding

This work is supported by Beijing Key Clinical Specialty for Laboratory Medicine – Excellent Project (No. ZK201000) and Chinese Academy of Medical Science and Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2017-I2M-2-001).

Disclosure

The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi:10.3322/caac.21492

2. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Erratum: global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(4):313. doi:10.3322/caac.21609

3. Arbyn M, Weiderpass E, Bruni L, et al. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(2):e191–e203. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30482-6

4. Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189(1):12–19. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F

5. Wang R, Pan W, Jin L, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccine against cervical cancer: opportunity and challenge. Cancer Lett. 2020;471:88–102. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2019.11.039

6. Lorincz AT, Reid R, Jenson BA, et al. Human papillomavirus infection of the cervix: relative risk associations of 15 common anogenital types. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79(3):328–337. doi:10.1097/00006250-199203000-00002

7. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 168: cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):e111–e130. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001708

8. Wardak S. Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer. Med Dosw Mikrobiol. 2016;68(1):73–84.

9. Rerucha CM, Caro RJ, Wheeler VL. Cervical cancer screening. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97(7):441–448.

10. Bedell SL, Goldstein LS, Goldstein AR, et al. Cervical cancer screening: past, present, and future. Sex Med Rev. 2020;8(1):28–37. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2019.09.005

11. Markowitz LE, Hariri S, Lin C, et al. Reduction in human papillomavirus (HPV) prevalence among young women following HPV vaccine introduction in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 2003–2010. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(3):385–393. doi:10.1093/infdis/jit192

12. Markowitz LE, Liu G, Hariri S, et al. Prevalence of HPV after introduction of the vaccination program in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20151968. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-1968

13. Barton MK. Declines in human papillomavirus infection observed in the vaccine era. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(6):369–370. doi:10.3322/caac.21200

14. de Sanjose S, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, et al. Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(7):453–459. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70158-5

15. Baloch Z, Yasmeen N, Li Y, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for human papillomavirus infection among Chinese ethnic women in southern of Yunnan, China. Braz J Infect Dis. 2017;21(3):325–332. doi:10.1016/j.bjid.2017.01.009

16. Ogembo RK, Gona PN, Seymour AJ, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus genotypes among African women with normal cervical cytology and neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122488. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0122488

17. Zhao XL, Hu S-Y, Zhang Q, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus genotype distribution and attribution to cervical cancer and precancerous lesions in a rural Chinese population. J Gynecol Oncol. 2017;28(4):e30. doi:10.3802/jgo.2017.28.e30

18. Melnikow J, Henderson JT, Burda BU, Senger CA, Durbin S, Soulsby MA. Screening for cervical cancer with high-risk human papillomavirus testing: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320(7):687–705. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.10400

19. Zhang C, Zhang C, Huang J, et al. Prevalence and genotype distribution of human papillomavirus among females in the suburb of Shanghai, China. J Med Virol. 2018;90(1):157–164. doi:10.1002/jmv.24899

20. Liu J, Ma S, Qin C, et al. Prevalence and genotype distribution of human papillomavirus in Zhengzhou, China, in 2016. Arch Virol. 2020;165(3):731–736. doi:10.1007/s00705-019-04515-3

21. Xiang F, Guan Q, Liu X, et al. Distribution characteristics of different human papillomavirus genotypes in women in Wuhan, China. J Clin Lab Anal. 2018;32(8):e22581. doi:10.1002/jcla.22581

22. Wang J, Tang D, Wang K, et al. HPV genotype prevalence and distribution during 2009–2018 in Xinjiang, China: baseline surveys prior to mass HPV vaccination. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):90. doi:10.1186/s12905-019-0785-3

23. Zhong TY, Zhou J-C, Hu R, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus infection among 71,435 women in Jiangxi Province, China. J Infect Public Health. 2017;10(6):783–788. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2017.01.011

24. Li B, Wang H, Yang D, et al. Prevalence and distribution of cervical human papillomavirus genotypes in women with cytological results from Sichuan province, China. J Med Virol. 2019;91(1):139–145. doi:10.1002/jmv.25255

25. Li Z, Liu F, Cheng S, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among 28,457 Chinese women in Yunnan Province, southwest China. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21039. doi:10.1038/srep21039

26. Chen X, Xu H, Xu W, et al. Prevalence and genotype distribution of human papillomavirus in 961,029 screening tests in southeastern China (Zhejiang Province) between 2011 and 2015. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14813. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-13299-y

27. Zhao P, Liu S, Zhong Z, et al. Prevalence and genotype distribution of human papillomavirus infection among women in northeastern Guangdong Province of China. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):204. doi:10.1186/s12879-018-3105-x

28. Zhang C, Cheng W, Liu Q, et al. Distribution of human papillomavirus infection: a population-based study of cervical samples from Jiangsu Province. Virol J. 2019;16(1):67. doi:10.1186/s12985-019-1175-z

29. Cao D, Zhang S, Zhang Q, et al. Prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus infection among women in Shaanxi province of China: a hospital-based investigation. J Med Virol. 2017;89(7):1281–1286. doi:10.1002/jmv.24748

30. Jiang L, Tian X, Peng D, et al. HPV prevalence and genotype distribution among women in Shandong Province, China: analysis of 94,489 HPV genotyping results from Shandong’s largest independent pathology laboratory. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0210311. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0210311

31. Ma L, Lei J, Ma L, et al. Characteristics of women infected with human papillomavirus in a tertiary hospital in Beijing China, 2014–2018. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):670. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4313-8

32. Zhu B, Liu Y, Zuo T, et al. The prevalence, trends, and geographical distribution of human papillomavirus infection in China: the pooled analysis of 1.7 million women. Cancer Med. 2019;8(11):5373–5385. doi:10.1002/cam4.2017

33. Wang R, Guo X-L, Wisman GBA, et al. Nationwide prevalence of human papillomavirus infection and viral genotype distribution in 37 cities in China. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:257. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-0998-5

34. Bruni L, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, et al. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(12):1789–1799. doi:10.1086/657321

35. Nogueira Dias Genta ML, Martins TR, Mendoza Lopez RV, et al. Multiple HPV genotype infection impact on invasive cervical cancer presentation and survival. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182854. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0182854

36. Wang L, Wu B, Li J, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus and its genotype among 1336 invasive cervical cancer patients in Hunan province, central south China. J Med Virol. 2015;87(3):516–521. doi:10.1002/jmv.24094

37. Steinau M, Hariri S, Gillison ML, et al. Prevalence of cervical and oral human papillomavirus infections among US women. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(11):1739–1743. doi:10.1093/infdis/jit799

38. Wendland EM, Villa LL, Unger ER, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among sexually active adolescents and young adults in Brazil: the POP-Brazil Study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):4920. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-61582-2

39. Farahmand M, Moghoofei M, Dorost A, et al. Prevalence and genotype distribution of genital human papillomavirus infection in female sex workers in the world: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1455. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09570-z

40. Winer RL, Hughes JP, Feng Q, et al. Early natural history of incident, type-specific human papillomavirus infections in newly sexually active young women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(4):699–707. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1108

41. Gonzalez P, Hildesheim A, Rodríguez AC, et al. Behavioral/lifestyle and immunologic factors associated with HPV infection among women older than 45 years. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(12):3044–3054. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0645

42. Rositch AF, Burke AE, Viscidi RP, et al. Contributions of recent and past sexual partnerships on incident human papillomavirus detection: acquisition and reactivation in older women. Cancer Res. 2012;72(23):6183–6190. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2635

43. Yip YC, Ngai KLK, Vong H-T, et al. Prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus infection in Macao. J Med Virol. 2010;82(10):1724–1729. doi:10.1002/jmv.21826

44. Li K, Li Q, Song L, et al. The distribution and prevalence of human papillomavirus in women in mainland China. Cancer. 2019;125(7):1030–1037. doi:10.1002/cncr.32003

45. Ouh YT, Min K-J, Cho HW, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus genotypes and precancerous cervical lesions in a screening population in the Republic of Korea, 2014–2016. J Gynecol Oncol. 2018;29(1):e14. doi:10.3802/jgo.2018.29.e14

46. Li K, Yin R, Wang D, et al. Human papillomavirus subtypes distribution among 2309 cervical cancer patients in West China. Oncotarget. 2017;8(17):28502–28509. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.16093

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.