Back to Journals » HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care » Volume 11

Prevalence And Associated Factors Of Enacted, Internalized And Anticipated Stigma Among People Living With HIV In South Africa: Results Of The First National Survey

Received 30 August 2019

Accepted for publication 26 September 2019

Published 7 November 2019 Volume 2019:11 Pages 275—285

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S229285

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Bassel Sawaya

Karl Peltzer,1 Supa Pengpid1,2

1Research and Innovation Office, North West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa; 2ASEAN Institute for Health Development, Mahidol University, Salaya, Nakhonpathom, Thailand

Correspondence: Karl Peltzer

Research and Innovation Office, North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus, 11 Hoffman Street, Potchefstroom 2531, South Africa

Email [email protected]

Background: This paper reports on the first national implementation of the “People Living with HIV (PLHIV) Stigma Index” in South Africa. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence and correlates of HIV-related stigma in a large sample of PLHIV in South Africa.

Methods: This cross-sectional survey interviewed 10,473 PLHIV 15 years and older with the PLHIV Stigma Index in two districts per province (N=9) in South Africa in 2014.

Results: The two most common enacted HIV-related stigma items were “being gossiped about” (20.6%) and “experienced discrimination” (15.1%); internalized stigma was ”blaming oneself” (30.5%) and ashamed (28.7%); avoidance due to internalized stigma was “decided not to have (more) children” (32.4%) and “decided not to get married” (14.9%), and the two most endorsed anticipated stigma were “being gossiped about” (28.6%) and not want to be sexually intimate (21.1%) Various sociodemographic factors, such as younger age, being female, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) and lower wealth status, and health-related variables, such as poorer self-rated health status, having a physical disability, and not being a member of an HIV support group, were identified as associated with overall HIV-related stigma as well as several HIV-related stigma sub-scales.

Conclusion: The majority of PLHIV had overall HIV-related stigma, almost half had internalized, or anticipated HIV-related stigma and a minority had enacted HIV-related stigma. Findings can be used to guide intervention programs to reduce HIV-related stigma in South Africa.

Keywords: HIV-related stigma, people living with HIV, survey, South Africa

Introduction

According to UNAIDS,

HIV-related stigma (irrational or negative attitudes, behaviors and judgments driven by fear) and discrimination (unfair treatment, laws and policies) are widespread, and persistent barriers to addressing the AIDS epidemic, restricting access to prevention, testing and treatment services for those most at risk.1

Stigma may be enacted (experience of exclusion or discrimination), internalized (acceptance of negative attributes), or anticipated (“expectation of future experiences of prejudice and stigmatizing behaviors”).2 With the roll-out of antiretroviral treatment (ART) in South Africa, one community study found that personal stigma had decreased, while perceived community stigma remained high,3 and in a qualitative study among people living with HIV (PLHIV) in an urban setting in South Africa, the HIV stigma experiences included “negative behavioral patterns and attitudes towards them, fear from the community of being infected by PLHIV and lastly negative self-judgement by PLHIV themselves”.4 South Africa has 7.2 million PLHIV and the largest ART program in the world.5 In an explorative study with the PLHIV stigma index in 10 HIV clinics in South Africa in 2012, it was found that PLHIV (N=486) experienced significant levels of HIV-related stigma and discrimination, e.g. the two most common types of enacted stigmata were “being gossiped about” (52.3%) and “verbally insulted/harassed or threatened” (28.3%) in the past 12 months, and the two most prevalent internalized stigmata were “blames self“ (49.2%) and “feels ashamed” (47.5%), the two most common types of avoidance due to internalized stigma were “decided not to have (more) children” (60.1%) and “decided not to get married” (30%) and two types of health care access avoidance due to internalized stigma were “avoided going to a clinic when needed to” (14.4%) and “avoided going to hospital when needed to” (8%).6

Factors associated with HIV-related stigma may include sociodemographic variables and health indicators. Sociodemographic factors associated with overall HIV-related stigma include, younger age,7–9 being female,10 being transgender,7 divorced/separated,8 lower income,11 lower education,11 higher education,8 and health factors include, longer time of HIV diagnosis,8 on ART7 and poorer self-reported health status.12 Factors associated with enacted stigma include sociodemographic indicators, such as being female,13 being single or widowed,13 lower education,13 and health indicators, coerced HIV testing decision,13 fewer years living with HIV,7 fewer years (0–3 years) on ART,13 self-rated health,7 and intimate partner violence.11 Factors associated with internalized stigma include sociodemographic indicators, including younger age,7 and lower education,13 and health indicators, such as HIV testing by coercion,13 not on ART,14 fewer years (0–1 year) on ART,13 not being member of PLHIV association.13 Factors associated with anticipated stigma may include HIV testing by coercion,13 fewer years (0–1 year) on ART,13 self-rated health,7 not being member of a PLHIV association.13

HIV-related stigma may impact negatively on the uptake of HIV services as well as psychosocial well-being of PLHIV.1,15 The South African National AIDS Council (SANAC) has noted that HIV stigma and discrimination of PLHIV need to be tackled, and consequently commissioned a national PLHIV Stigma Index study.16 The “People Living with HIV Stigma Index” is a joint initiative of several organizations including PLHIV organizations and UNAIDS, and has been implemented in over 50 countries.16 In order to design an HIV-related stigma reduction program, it is important to understand the extent and its correlates of overall HIV-related stigma as well as its different components. This paper reports on the first national implementation of the (PLHIV) Stigma Index in South Africa. The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence and correlates of HIV-related stigma in a large sample of PLHIV in South Africa.

Methods

Sample And Procedure

This cross-sectional survey interviewed 10,473 PLHIV 15 years and older with the PLHIV Stigma Index in two districts per province (N=9) in South Africa in 2014.16 Most participants were enrolled through participating in the support group “Networks of National Association of People Living with HIV and AIDS (NAPWA), Treatment Action Campaign (TAC), and Positive Women’s Network (PWN).”16 Other study participants were enrolled through health service providers.16 Some of the PLHIV that were affiliated with a support organization were trained as interviewers and team supervisors.16 The study protocol was approved by the Human Sciences Research Council Research Ethics Committee, and written informed consent was obtained from participants prior to the interview. Participants under the age of 18 years were able to provide informed consent on their own behalf, which was approved by the Human Sciences Research Council Research Ethics Committee.

Measures

Sociodemographic and health questions included, age, HIV test decision modalities, years of living with HIV, on ART, relationship status, currently sexually active, having a physical disability (excluding HIV), formal education, residence, subjective wealth status, self-rated health status, and currently member of PLHIV support group. Sex and sexual orientation were assessed with two questions, 1) sex (male, female, transgender) and 2) identify yourself as “men who have sex with men”, “gay or lesbian” and “transgender.”16 Responses from the two questions were combined and grouped into male, female and lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT).

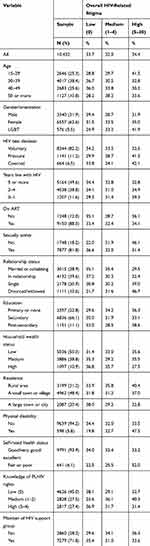

HIV-related stigma was assessed with the PLHIV Stigma Index,16–18 including enacted, internalized and anticipated HIV-related stigma. Enacted stigma included 10 items (Cronbach alpha 0.78); see items in Table 1. A positive score was given provided that the event occurred once or more often in the past 12 months and if it was “because of your HIV status” or “both because of your HIV status and other reason(s)”.

|

Table 1 Sample Characteristics And Overall HIV-Related Stigma |

Internalized stigma was assessed with seven questions, if they experienced, e.g., feeling ashamed because of their HIV status (Yes, No) (Cronbach alpha 0.87), and Avoidance due to internalized stigma was measured with 10 items, if they had, e.g., chosen not to attend social gatherings because of their HIV status (Yes, No) (Cronbach alpha 0.77); see items in Table 1.

Anticipated stigma was measured with five items (Yes, No) (Cronbach alpha 0.81); see items in Table 1. Overall HIV-related stigma was calculated by adding all items up and divided into 0=low 1-4=medium and 5-30=high stigma.

Knowledge of PLHIV rights was assessed with four items, 1) “Have you heard the Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS, which protects the rights of PLHIV?”, 2) … read or discussed the Declaration, 3) “Have you heard of the National Strategic Plan (NSP) which protects the rights of PLHIV in this country?”, and 4) … read or discussed the NSP (Cronbach alpha 0.86). Items were summed and classified into 0=low, 1–2 medium and 3–4 high knowledge of rights.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted with “IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.)”. In order to describe the sample, descriptive statistics was used. Multinomial logistic regression was used to predict the associations between independent variables (sociodemographic and health-related items) and dependent variables of medium and high overall HIV-related stigma, with no HIV-related stigma as reference category. Logistic regression was used to assess the predictors of each the HIV-related stigma sub-scales. Due to the large sample size, P<0.01 was regarded as statistically significant. Multicollinearity was checked and not found an issue. Missing values (27.6%) were excluded from the analysis.

Results

Sample And HIV-Related Stigma Characteristics

The sample included 10,432 PLHIV 15 years and older, 31.9% were male, 62.6% were female and 5.5% were LGBT. More than one in 10 participants (11.2%) were under pressure from others and 6.5% were “made to take an HIV test (coercion).” About half (49.6%) had been living with HIV for five or more years, 88.0% were on ART and 12.0% were not, and 81.8% were sexually active. Two in five of PLHIV (39.6%) were “in a relationship but not living together”, 72.2% had secondary or more education, 50.3% rated themselves as having a low household wealth status, and 48.4% were living in a small town or village. A minority (6.1%) rated their health as fair or poor, 5.8% had a physical disability, 71.8% were a member of a support group and 55.0% had medium or high knowledge of rights. About one-third of participants (33.7%) reported no overall HIV-related stigma, 32.0% medium and 34.4% high overall HIV-related stigma (see Table 1).

The three most common enacted stigma items were “being gossiped about” (20.6%), “experienced discrimination” (15.1%) and “verbally insulted and harassment” (10.6%). Likewise, the three most common internalized stigma were blaming oneself (30.5%), ashamed (28.7%) and guilty (28.0%), and the two most prevalent avoidance due to internalized stigma were “decided not to have (more) children” (32.4%) and “decided not to get married” (14.9%). The two most endorsed anticipated stigma were “being gossiped about” (28.6%) and not want to be sexually intimate (21.1%) (see Table 2).

|

Table 2 Experiences Of HIV-Related Stigma In The Past 12 Months At Least Once (N=10,432) |

The prevalence of enacted stigma was 29.0%, internalized stigma 43.0%, avoidance due to internalized stigma 41.9% and anticipated stigma 39.1% (see Table 3).

|

Table 3 Description Of HIV-Related Stigma Sub-Scales (N=10,473) |

Associations With Overall HIV-Related Stigma

In adjusted multinomial logistic regression, younger age, being female and being LGBT, lower household wealth status, being separated, divorced or widowed, residing in a small town or village, having a physical disability, poorer self-rated health status and medium knowledge of rights of PLHIV were associated with medium and/or high overall HIV-related stigma. Being sexually active and being a member of an HIV support group were negatively associated with medium and overall HIV-related stigma (see Table 4).

|

Table 4 Multinomial Regression Results With Overall Medium And High HIV-Related Stigma (With No HIV-Related Stigma As Reference Category) |

Associations With HIV-Related Stigma Sub-Scales

In adjusted logistic regression analysis, younger age was associated with enacted, internalized and anticipated stigma but not with avoidance due to internalized stigma. Being female and LGBT increased the odds for enacted stigma, avoidance due to internalized stigma and/or anticipated stigma. Pressured and/or coerced HIV testing decision was associated with internalized and anticipated stigma. Newly diagnosed with HIV (0–1 year) increased the likelihood of internalized stigma. Being on ART was protective from internalized stigma and being sexually active was protective from internalized and anticipated stigma. In a relationship but not living together reduced the odds for avoidance due to internalized stigma, being single increased the odds for avoidance due to internalized stigma and being divorced or widowed increased the odds for avoidance due to internalized stigma and anticipated stigma. Higher household wealth decreased the likelihood of enacted stigma and avoidance due to internalized stigma. Living in a non-rural area increased the odds for enacted stigma and avoidance due to internalized stigma and decreased the odds for internalized stigma. Physical disability and poorer self-rated health status were associated with all five HIV-related stigma sub-scales. Medium or high knowledge on PLHIV rights were positively associated with four of the HIV-related stigma sub-scales. Being a member of an HIV support group was protective from internalized and anticipated stigma but increased the odds for enacted stigma (see Table 5).

|

Table 5 Associations With HIV-Related Stigma Sub-Scales |

Discussion

This study reports for the first time national data on the prevalence and correlates of HIV-related stigma in South Africa.16 Even though the study sample was not nationally representative, compared to a small sample of PLHIV from HIV clinics in 2012 in South Africa, this study seems to show a reduction of HIV-related stigma. For example, internalized stigma items “blames self” reduced from 49.2% to 30.5% and “feels ashamed” reduced from 47.5% to 28.7%, the avoidance due to internalized stigma items “decided not to have (more) children” reduced from 60.1% to 32.4%, “decided not to get married” from 30% to 14.9%, “avoided going to a clinic when needed“ to from 14.4% to 4.8% and “avoided going to hospital when needed to” from 8% to 3.4%.6 Consistent with some other studies,8 this study found that internalized and anticipated stigma were more common than enacted (experienced) stigma.

Consistent with some previous studies,7–9 this study found that younger age was associated with overall HIV-related stigma and most HIV-related subscales. It is possible that HIV becomes more acceptable with increasing age8 and that age maturation provides resilience against stigma.7 Being female and LGBT were associated with overall HIV-related stigma and several HIV-related subscales. Similar results were found in previous studies,7,10,13 which found that being female and transgender was associated with overall and enacted HIV-related stigma. It is possible that women and LGBT become more target of HIV-related stigma due to existing prejudices against them.8,13 The study found that participants who were divorced or widowed had a higher overall HIV-related stigma. Similar results were found in previous studies8 and may be possible due to lack of support.

In agreement with some studies,11 this study found a negative association between lower subjective household wealth status and overall, enacted and internalized HIV-related stigma, while no associations were found regarding educational status, as in some previous studies.8,11,13 Non-urban residence increased the odds for overall HIV-related stigma, harassment enacted stigma and avoidance due to internalized stigma but decreased internalized stigma.

Shorter period (0–1 year) of living with HIV was in unadjusted analysis associated with overall HIV-related stigma, and in adjusted analysis with internalized stigma but not enacted stigma. In a previous study among ART patients, shorter period (0–1 year) on ART was also associated with internalized stigma.13 In a longitudinal study among ART patients in South Africa, a decrease in HIV-related stigma was found.19 While some previous studies7,13,14 found that being on ART was protective from overall HIV-related stigma, internalized and anticipated stigma, this study found only a protective effect for internalized stigma. Having a physical disability and poorer self-rated health status increased the odds for overall HIV-related stigma and all HIV-related stigma subscales, while previous studies found an association between poorer self-rated health status and enacted and anticipated stigma.7,12 Some previous studies13 found an association between coercive HIV testing decision and enacted, internalized and anticipated stigma, while in this study, pressured and/or coerced HIV testing decision were associated with internalized and anticipated stigma.

As found in some previous investigations,13 this study found that being a member of an HIV support group was protective from overall, internalized and anticipated HIV-related stigma. It is possible that HIV support groups provide psychosocial support and increase self-esteem that reduces, in particular, internalized and anticipated HIV-related stigma.13 Compared to PLHIV in this study that had no knowledge of PLHIV rights, PLHIV with medium and/or high knowledge of PLHIV rights reported higher overall, enacted, internalized and anticipated HIV-related stigma. It is possible that through the experience of HIV-related stigma participants in the search for solutions became more aware of PLHIV rights. Lastly, being sexually active was protective from overall HIV-related stigma, in particular, internalized and anticipated HIV-related stigma. Sexually active PLHIV may be more resilient than sexually inactive PLHIV, which may help in warding off internalized and anticipated HIV-related stigma.

Study Limitation

Although the study was able to recruit a large number of PLHIV in South Africa, the sample may not be representative of the whole country. Several factors that may be related to HIV-related stigma, such as ART adherence, substance use, and other clinical indicators, were not assessed in this study, and may be included in future investigations. The study was not able to determine the direction of a relationship, e.g. between poorer self-reported health status and HIV-related stigma; did the HIV-related stigma experience lead to poorer self-reported health or vice versa, since the study used a cross-sectional design.

Conclusion

The study found that the majority of PLHIV had overall HIV-related stigma, almost half had internalized, or anticipated HIV-related stigma and a minority had enacted HIV-related stigma. Various sociodemographic factors, such as younger age, being female, LGBT and lower wealth status, and health-related variables, such as poorer self-rated health status, having a physical disability, and not being a member of an HIV support group, were identified as associated with overall HIV-related stigma as well as several HIV-related stigma sub-scales. These findings can be used to guide intervention programs to reduce HIV-related stigma in South Africa. This could be in the form of a national HIGV stigma mitigation campaign and strengthening existing support group structures in providing psychosocial support for PLHIV.

Acknowledgments

Human Sciences Research Council, University of Witwatersrand Reproductive Health and HIV Institute & South African National AIDS Council. People living with HIV Stigma Index: South Africa (STIGMA) 2014. [Data set]. STIGMA 2014. Version 1.0. South Africa: University of Witwatersrand Reproductive Health and HIV Institute, Human Sciences Research Council, South African National AIDS Council [producers] 2014. Human Sciences Research Council [distributor] 2019. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.14749/1553526054.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. UNAIDS. Global partnership for action to eliminate all forms of HIV-related stigma and discrimination, 2018. Available fom: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2018/global-partnership-hiv-stigma-discrimination.

2. Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, Copenhaver MM. HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: a test of the HIV stigma framework AIDS and behavior. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1785–1795.

3. Visser M. Change in HIV-related stigma in South Africa between 2004 and 2016: a cross-sectional community study. AIDS Care. 2018;30(6):734–738. doi:10.1080/09540121.2018.1425365

4. French H, Greeff M, Watson MJ, Doak CM. HIV stigma and disclosure experiences of people living with HIV in an urban and a rural setting. AIDS Care. 2015;27(8):1042–1046. doi:10.1080/09540121.2015.1020747

5. Avert. HIV and AIDS in South Africa, 2019. Available from: https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/south-africa.

6. Dos Santos MM, Kruger P, Mellors SE, Wolvaardt G, van der Ryst E. An exploratory survey measuring stigma and discrimination experienced by people living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa: the people living with HIV stigma index. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:80. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-80

7. Bagchi AD, Holzemer W, Peavy D. Predictors of enacted, internal, and anticipated stigma among PLHIV in New Jersey. AIDS Care. 2019;31(7):827–835. doi:10.1080/09540121.2018.1554242

8. Subedi B, Timilsina BD, Tamrakar N. Perceived stigma among people living with HIV/AIDS in Pokhara, Nepal. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2019;11:93–103. eCollection 2019. doi:10.2147/HIV.S181231

9. Emlet CA, Brennan DJ, Brennenstuhl S, Rueda S, Hart TA, Rourke SB. The impact of HIV-related stigma on older and younger adults living with HIV disease: does age matter? AIDS Care. 2015;27(4):520–528. doi:10.1080/09540121.2014.978734

10. Blessed NO, Ogbalu AI. Experience of HIV-related stigma by people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), based on gender: a case of PLWHA attending clinic in the federal medical center, Owerri, IMO states, Nigeria. J Public Health Epidemiol. 2013;1(1):32–36.

11. Ramlagan S, Sifunda S, Peltzer K, Jean J, Ruiter RAC. Correlates of perceived HIV-related stigma among HIV positive pregnant women in rural Mpumalanga province, South Africa. J Psychol Afr. 2019;29(2):141–148. doi:10.1080/14330237.2019.1603022

12. Li X, Wang H, Williams A, He G. Stigma reported by people living with HIV in south central China. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20(1):22–30. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2008.09.007

13. Nikus Fido N, Aman M, Brihnu Z. HIV stigma and associated factors among antiretroviral treatment clients in Jimma town, Southwest Ethiopia. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2016;8:183–193. eCollection 2016. doi:10.2147/HIV.S114177

14. Chan BT, Maughan-Brown BG, Bogart LM, et al. Trajectories of HIV-related internalized stigma and disclosure concerns among ART initiators and noninitiators in South Africa. Stigma Health. 2019. doi:10.1037/sah0000159

15. Zhang C, Li X, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Shen Z, Chen Y. Impacts of HIV stigma on psychosocial well-being and substance use behaviors among people living with HIV/AIDS in China: across the life span. AIDS Educ Prev. 2018;30(2):108–119. doi:10.1521/aeap.2018.30.2.108

16. Simbayi L, Zuma K, Cloete A, et al. The people: living with HIV stigma index: South Africa 2014: summary report, 2015. (Commissioned by the South African National AIDS Council)

17. Friedland BA, Sprague L, Nyblade L, et al. Measuring intersecting stigma among key populations living with HIV: implementing the people living with HIV stigma index 2.0. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(Suppl 5):e25131. doi:10.1002/jia2.25131

18. Global Network of People Living with HIV. The people living with HIV stigma index, 2019. Available from: https://www.gnpplus.net/our-solutions/hiv-stigma-index-2/.

19. Peltzer K, Ramlagan S. Perceived stigma among patients receiving antiretroviral treatment: a prospective study in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2011;23(1):60–68. doi:10.1080/09540121.2010.498864

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.