Back to Journals » HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care » Volume 13

Predictors of Mortality Among Adult HIV-Infected Patients Taking Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) in Harari Hospitals, Ethiopia

Authors Birhanu A , Dingeta T, Tolera M

Received 3 March 2021

Accepted for publication 19 June 2021

Published 2 July 2021 Volume 2021:13 Pages 727—736

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S309018

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Editor who approved publication: Professor Bassel Sawaya

Abdi Birhanu,1 Tariku Dingeta,2 Moti Tolera2

1School of Medicine, College of Health and Medical Science, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia; 2School of Public Health, College of Health and Medical Science, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Abdi Birhanu

School of Medicine, College of Health and Medical Science, Haramaya University, PO Box: 235, Harar, Ethiopia

Tel +251917094058

Email [email protected]

Introduction: Despite the world has made efforts, the reduction of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) related mortality by giving antiretroviral therapy (ART), still HIV/AIDS is killing people while they are on ART. However, the current progress and associated factors of mortality among ART-taking patients are hardly available. Therefore, this study was aimed to determine predictors of mortality among HIV-infected adult patients after starting antiretroviral therapy in Harar Hospitals, Harari region, Ethiopia.

Methods: A facility-based retrospective cohort study was employed with randomly selected 610 medical records of HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy (ART). Adjusted hazard ratio (AHR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to identify predictors of mortality using multivariate Cox proportional hazard model.

Results: Among 610 medical records analyzed with a total of 1410.7 follow-up years, 67 (11%) deaths were found giving an overall mortality rate of 4.75 per 100 person-years. The independent predictor of mortality identified was ambulatory/bedridden functional status (AHR=2.48; 95% CI: 1.43– 4.28), taking other than Tenofovir-based regimen (AHR=2.5,95% CI; 1.04– 5.94), not taking isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) (AHR=2.8; 95% CI: 1.61,4.71), hemoglobin < 11g/dl (AHR=3.33,95% CI 1.94– 5.69), and poor adherence to ART (AHR= 3.62, 95% CI: 1.87– 7.0).

Conclusion: This study demonstrated that poor ART adherence, not taking IPT, and initiating ART with a non-Tenofovir-based regimen and low hemoglobin count were significantly associated with the risk of death. For this reason, addressing these all significant predictors is essential to prevent early death.

Keywords: predictors, mortality, HIV, ART, adult, Ethiopia

Introduction

In resource-poor setting countries, HIV/AIDS is still a continuing puzzle1 which induced the death of about 1.2 million people worldwide in 2014.2 UNAIDS and World Health Organization data showed that this world lost nearly two million people due to AIDS in 2015 and 2018.3,4 Recently, in African regions, despite the world’s proposal to decline AIDS-related deaths, the mortality was increased by 11% that caused the death of more than half of a million people.4 Despite Ethiopia realized striking progress in reducing HIV-related death and morbidity through aggressive ART provision, still, there were 5–40.8% of HIV/AIDS-related deaths within 5 years of initiation.5–7

Different studies showed that the survival status of HIV-infected patients might be affected by advanced HIV stage, severe immunodeficiency, co-morbidity, low hemoglobin count, low body mass index, low CD4 counts, malnourished, poor functional status, low economic status and not taking prophylaxis treatment.8–14 However, these prognostic factors are not well characterized in Ethiopia because of which it is hard to identify the most contributing factors for mortality among patients on ART follow-up. A better understanding of these factors would allow care providers in the closer follow-up in high-risk patients for the reduction of early mortality.15 Thus, this study may be helpful for health service providers in the identification and rectification of these modifiable factors during regular care, counseling, and screening to prolong patients’ survival. Therefore, this study was aimed to determine the predictors of mortality among HIV-infected adult patients on ART care at the hospital in the Harari region, Ethiopia.

Methods and Materials

Study Design, Setting, and Period

A hospital-based retrospective study design was conducted in the Harari regional state of Ethiopia. Harari is a region located 525 kilometers away from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. In the region, there are two public hospitals (Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Jugol Hospital), one Police Hospital, two private general hospitals, one Fistula center, eight government health centers, and 28 health posts (5 urban and 23 rural health posts). Among these, the study was conducted at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Jugol Hospital, and Federal Police Harari Hospital. The first two hospitals provide ART care for all segments of the population while Federal police Harari Hospital provides care for the police and family members.16 These data were extracted from March 05 to March 27, 2019, from patient recorded from September 2013 to June 30, 2018.

Study Population and Eligibility Criteria

All HIV-infected adult patients who were on ART in Harar government hospitals ART clinics between September 2013 and June 2018 were included in the study. The eligibility criteria of the study were age 15 and above years, not starting ART for prevention of maternal to child transmission purpose, having a date of death for deceased patients, and starting the ART follow-up within the study hospitals.

Sampling Technique, Procedure, and Sample Size Calculation

Sample size was determined using estimated sample size for Cox Proportional Hazard (PH) regression in STATA version 13.0 software with the power of 80%, type I error (α) of 5%, standard deviation (SD)=0.5 (default value), 10% of loss of follow up. Hazard ratio (HR=0.8) of male gender compared to female was used as a predictor of death.13 Based on this the total sample size was determined to be 631. Regarding sampling technique, all eligible patients, enrolled in ART between September 2013 and December 2018 in the three hospitals were generated and merged by using a unique ART registration number from an electronic database. Then sample frame of all eligible patients was prepared. The sampling frame was used to select 631 medical records by using a simple random sampling method. Finally, medical records were distributed to each hospital based on their unique ART registration number (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1 Procedure for extraction of eligible ART patients’ medical records. |

Study Variables and Measurements

Death was considered a dependent variable. The death was ascertained from patients’ medical records and registrations at the ART clinic reported by adherence supporters during the follow-up period.17 Independent variable included sex, age, educational status, employment status, residence, religion, marital status, CD4 count, bedridden functional status, new TB cases, BMI, weight, hemoglobin level, opportunistic infections, ART Adherence, ART Regimen, IPT, and CPT prophylaxis status, and WHO clinical stages. As seen in the Supplementary Material, according to the revised World Health Organization (WHO) clinical staging of HIV/AIDS for adults and adolescents, HIV/AIDS clinical stages were classified into four stages; Stage one, stage two, stage three, and stage four.

The patient was categorized as an isoniazid preventive therapy user if took IPT for at least six months otherwise designated as a non-IPT user if the patient did not take it at all.18 ART adherence was defined as good: if <5% doses are missed (<2 doses of 30 doses or <3 doses of 60 doses) as documented by ART physician, Fair: if between 5−15% doses are missed (3–5 doses of 30 doses or 3−9 doses of 60 doses) as documented by ART physician, Poor: if >15% doses are missed (>6 doses of 30 doses or >9 doses of 60 doses) as documented by ART physician.17 A patient on ART who took CPT for at least one month was considered as using CPT for a prophylaxis purpose.19 Functional status of clients was labeled as follows: working, to refer to clients who can perform usual work in or out of the house; ambulatory, to refer to clients able to perform activities of daily living; and bedridden, designated to clients who are not able to perform activities of daily living.20

Data Collection and Quality Control

A standardized ART data entry and follow-up form were used for the extraction of data from electronic databases and patient’s medical records. The checklist consists of variables at ART initiation and during follow-ups such as sex, age, marital status, educational status, occupational status, CD4 cell count, weight (kg), hemoglobin (g/dl), WHO clinical stages, opportunistic infections, initial ART regimen, CPT and IPT prophylaxis. Data were collected by trained five nurses who had ART training and the data collection process was supervised by two senior ART trained supervisors. During the data extraction period, the extracted data were checked for completeness, consistency, and accuracy by the supervisors every day.

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

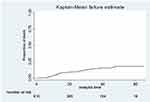

Data were entered into Epi-Data software 3.1 version and analyzed STATA 13.0 analysis software (College Station, Texas, USA). Additionally, all randomly selected study subjects were followed until December 31, 2018, retrospectively. Among 631 randomly selected study subjects, 21 of them had an incomplete record which could not able us to entertain their outcome and they were excluded from the final model. Those patients who were lost to follow-up, study cessation year (31st, December 2018), died, or who transferred out of the area were considered as censorship states during the analysis. Every patient was followed until the occurrence of an event (mortality) or any of the censorship states which occurred first. A descriptive data summary was done by running frequencies, mean, median, standard deviation, and range. Survival analysis was the appropriate statistical model to estimate associations of death with its predictors which were presented as a hazard ratio. The model fitness was checked by using a graphical and Schoenfeld residuals model fitness test for the proportional-hazards assumption test. Time to death was calculated in months using the time interval between dates registered on ART initiation to the date of death registered or censoring. Kaplan–Meier method was used to calculate the probability of survival status. A life table was used to estimate cumulative probabilities of survival status.

The crude hazard ratio test was used for the inclusion of variables into multivariate analysis. Cox proportional hazard model was used to identify factors associated with death with controlling confounders. Statistically, the significance level was declared to be p-value < 0.05 at a 95% confidence level. The multivariate model was built using purposeful selection with a backward elimination method.21 VIF < 10 indicating the non-existence of multi-collinearity among the variables in this study. Both statistical and graphical test results showed that none of the predictors violated the proportional hazard assumptions and there was no strong evidence of non-fit.

Ethical Statement

Haramaya University College of health and medical sciences Institutional Health Research Ethical Review Committee (IHRERC) ethically cleared the paper. A letter of permission was sent from the College of Health to Hiwot Fana specialized University Hospital, Jugol Hospital, and Federal Police Harar Hospital. Due to difficulty to reach patients to take informed consent, the institutional review board has waived the need for patient consent documentation processes. Finally, data were obtained from patient’s medical records anonymously guaranteeing information confidentiality, and all data extraction processes were conducted per the declaration of Helsinki. The collected data was used only for the intended purpose.

Results

Background Characteristics of Study Subjects

A total of 610 patient records enrolled on ART were included in the analysis. The mean age of patients was 33.9 years the standard deviation of 4.2 (33.9 +4.2) at ART initiation. Out of a total participants nearly half, 278 (45.6%) were recruited from Hiwot Fana specialized University Hospital. The majority, 356 (58.4%) of the study subjects were females. More than half of the study participants; 348 (57%) were Orthodox religious followers. Regarding disclosure status, 344 (56.4%) had not disclosed their serostatus. Out of the total study subjects, 563 (92.2%) were urban residents (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of HIV-Infected Adult Patients on ART in Harari Region Hospitals, Ethiopia, March 2019 (n=610) |

Clinical and Immunological Characteristics of the Study Subjects

Out of 610 study subjects, 352 (57.7%) were on the WHO clinical stage I/II at ART initiation. The majority 353 (57.9%) had 40–60 kg of weight at ART initiation, while 442 (72.5%) of them had BMI 18.5 Kg/m2 and above. Nearly three-fourth of the study subjects had <350cells/mm3 CD4 count and >11gm/dl hemoglobin count at baseline. The majority, 591 (96.9%) of study participants started the initial ART regimen with Tenofovir-Lamivudine-Efavirenz. Of these initial regimens, 594 (97.4%) of them did not get a change of the regimen. Among sixteen participants who changed the initial regimen, eleven of them were to first-line ART regimen. Out of the total participants, 581 (95.9%) had good ART adherence at the first evaluation period of adherence. Regarding prophylaxis provided during ART follow-up care, 323 (53%) of subjects used IPT for at least six months while 482 (79.1%) of subjects used cotrimoxazole for at least one month after ART initiation (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Clinical and Immunological Characteristics of HIV-Infected Adult Patients on ART in Harari Region Hospitals, Ethiopia, March 2019 (n=610) |

Six hundred ten patients were followed for the median follow-up of 25.7 months (IQR: 12.8–40). Out of 610 study subjects, 67 (11%) died, while 543 (89%) censored for alive (403), transferred out (98), and lost to follow-up (42). Over the five years of the follow-up period, the overall mortality rate was 4.75 (95% CI: 3.7–6) per 100PYO with a total of 1410.7 follow-up years. The median time to death was 13.5 months (IQR: 9.5–26.3). The baseline median BMI (Kg/m2) was increased by 1.3 Kg/m2 from 20.8 Kg/m2 (IQR=18.1–23.1) to 22.1 Kg/m2 (IQR=21–25.6) after five years of ART initiation. The baseline median hemoglobin count was increased by 1.3gm/dl from 12.1 gm/dl (IQR=11.1–12.4) to 12.5g/dl (IQR=11.7–14.3) after five years of ART initiation. The baseline median CD4 count was increased by 330cells/mm3 from 234 cells/mm3 (IQR=117–395) to 564 cells/mm3 (IQR=367–786) after five years of ART initiation.

Predictors of Mortality

This study showed that ART patients who started ART with other than Tenofovir-Lamivudine-Efavirenz regimen had hazard of death 2.543 times more likely compared to those who started AR with Tenofovir-Lamivudine-Efavirenz regimen (AHR=2.543, 95% CI; 1.04–5.94). Not taking IPT increased early death by 2.823 times more likely compared to individuals who took IPT (AHR=2.823, 95% CI: 1.61–4.71). Moreover, ambulatory/bedridden functional status compared to working functional status (AHR=2.483, 95% CI: 1.43–4.28), baseline hemoglobin level <11 g/dl (AHR=3.331, 95% CI; 1.94–5.69), and poor ART adherent (AHR=3.624, 95% CI: 1.87–7) were associated with higher likely odd of early death (Table 3 and Figure 2).

|

Table 3 Multivariable Cox Regression Analysis of Risk of Death Among HIV-Infected Adult Patients on ART in Harari Region Hospitals, Ethiopia, March 2019 (n=610) |

|

Figure 2 Kaplan–Meier probability of survival curve among HIV-infected adult patients initiated ART in Harar Hospitals, East Ethiopia, 2019. |

Discussion

Despite immense advancements in antiretroviral therapy and global movement in the path of enactment of treatment-as-prevention schemes, nearly two million people turn out to be newly infected by HIV every year. On top of that, a year back, over 39 million HIV/AIDS-related diseases were recorded globally.22 This study showed that from the registered ART cohort, there were 67 deaths from 1410.7 person-years of retrospective follow-up, providing an incidence rate of 4.75 deaths per 100 person-year observations.

The incidence rate of death in the current study is higher than the incidence of death from studies conducted in other parts of Ethiopia.23–25 This difference might be due to differences in study population and study period. However, the finding from the current study was comparable with findings from northern Ethiopia,26 India,27 and multination study.28 The consistency of these findings reconfirmed that the incidence of death among ART taking HIV/AIDS patients is still imposing a significant hardship on the life of people in different corners of this world.

According to the management guideline, IPT should be given to all eligible HIV/AIDS patients to lessen the risk of developing one of the important HIV opportunistic infections, tuberculosis. However, due to patient’s refusal, experiencing a high level of HIV stigma, occurrences of opportunistic infections, irregularity of follow-up attending, lack of detail elucidation about the benefit of IPT from healthcare workers, and developing IPT associated adverse effect.29,30 In the present study due to possibly similar reasons, the patients who did not take IPT for at least six months had a higher risk of death from HIV/AIDS. This finding was consistent with study findings from the Tigray region,8 Amhara region,31 Addis Ababa,32 Southern Ethiopia,33 and Zimbabwe.34 This similarity might deep-rooted the value of taking IPT for at least six months to reduce TB incidence that indirectly results in the reduction of risk of death from HIV/AIDS

The nonworking functional status of the study participants had higher hazards of deaths among HIV/AIDS patients taking ART than their counterparts. The finding was in line with the study conducted in South Ethiopia,35,36 the Amhara region,26 Somali region, Ethiopia,17 Kenya,37 and India.38 It is a fact that patients with advanced clinical stages of HIV/AIDS due to super-infected with opportunistic infections and cancers, may be presented with deteriorated quality of life such as unable to perform daily living activities like bathing, eating, and clothing. Due to their restriction on a bed, the patients may be psychologically affected. These all factors may worsen the poor prognosis of patients with HIV/AIDS.

Patients with baseline hemoglobin count less than 11 g/dl had higher hazards of deaths by HIV compared to those who had hemoglobin counts greater than or equal to 11 g/dl at baseline. This finding is supported by findings from Tanzania,14 Indonesia,39 and Hispanics,40 and the northern part of Ethiopia.23,24,41 Anemia is the top common hematological disorder of HIV infection that has a substantial negative effect on the quality of life and costs the patient’s life. This is because anemic patients, as a consequence of super-imposed to HIV, need additional time to get well from their sickness or turn into completely incompetent for the expected prognosis of salvage from the infection nonetheless they are taking ART. Overwhelmingly, this threatening progress of the disease may end up in the loss of patient life.

HIV-infected patients with poor ART adherence had a higher risk of death compared to those who had good ART adherence scores. This finding is agreed with the study findings from Northern Ethiopia,26 India,27 Arba Minch,42 Southwestern Ethiopia,43 and Jharkhand, India.44 This can be due to forgetting about taking ARV drugs, late initiation of the follow-up care, lack of close supervision and counsel from adherence supporters, and follow-up interruptions due to the patients and health facility/health care worker’s factors. These all factors may affect the adherence level of ART that results from the treatment failure that ended with a low patient survival rate.

Moreover, the ART patients who commenced ART with a non-Tenofovir-Lamivudine-Efavirenz regimen had a higher hazard of death compared to patients who started ART with Tenofovir-Lamivudine-Efavirenz regimen. This finding was supported by the study findings from Kenya,37 China,45,46 and Brazil,47 and Addis Ababa.48 This can be because TDF-based regimens are characterized by lighter adherence-related problems, adverse drug reactions, virological failure, and drug resistances compared to other regimens. As a limitation, the study did not cover viral load since the variable was available for a few subjects. Besides, we could not measure variables that show the economic status of the patient due to the nature of the retrospective study. Another limitation can be the cause of death. We considered all-cause mortality in the analysis. There is an expectation that some deaths might be occurred due to causes other than HIV/AIDS.

Conclusion and Recommendation

This study demonstrated that there was a high mortality rate in 1410.7 person-years contributions. Poor ART adherence, not taking IPT, ambulatory/bedridden, starting ART regimen other than Tenofovir-Lamivudine-Efavirenz and hemoglobin <11g/dl had statistically, significant association with mortality. For this reason, efforts should be strengthened on these significantly contributing predictors of mortality to improve patient’s survival status. In addition, we recommend prospective studies to address the variables that cannot be measured by retrospective studies.

Abbreviations

ART, antiretroviral therapy; CD4, cluster deferential 4; CPT, cotri-moxazole therapy; FPHH, Federal Police Harar Hospital; IPT, isoniazid preventive therapy; JH, Jugol Hospital; TDF-3L-EV, Tenofovir-Lamivudine-Efavirenz; PYO, person-year observation.

Data Sharing Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Haramaya University College of health and medical science. We would also like to thank Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Jugol Hospital, and Federal Police Harar Hospital staff for their assistance and help in facilitating the data extraction. Finally, our gratitude goes to our data collectors and supervisors for their commitment to the data extraction process.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Gunda DW, Nkandala I, Kilonzo SB, Kilangi BB, Mpondo BC. Prevalence and risk factors of mortality among adult HIV patients initiating ART in rural setting of HIV care and treatment services in North Western Tanzania: a retrospective cohort study. J Sexual Transmit Dis. 2017;2017:2017. doi:10.1155/2017/7075601

2. WHO. Global Health Sector Response to HIV, 2000–2015: Focus on Innovations in Africa: Progress Report. WHO; 2015.

3. World Health Organization. Global Health Sector Strategy on HIV 2016–2021. Towards Ending AIDS. World Health Organization; 2016.

4. HIV/AIDS JUNPo, HIV/AIDS JUNPo. Global AIDS Update 2016. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2016.

5. Ethiopia FMoH. National guidelines for comprehensive HIV prevention, care and treatment View. 2014.

6. WHO. Guidelines for Antiretroviral Drug Therapy in Kenya. WHO; 2005.

7. Biset Ayalew M. Mortality and its predictors among HIV infected patients taking antiretroviral treatment in Ethiopia: a systematic review. AIDS Res Treat. 2017;2017:5415298. doi:10.1155/2017/5415298

8. Misgina KH, Weldu MG, Gebremariam TH, et al. Predictors of mortality among adult people living with HIV/AIDS on antiretroviral therapy at Suhul Hospital, Tigrai, Northern Ethiopia: a retrospective follow-up study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2019;38(1):37. doi:10.1186/s41043-019-0194-0

9. Kebede A, Tessema F, Bekele G, Kura Z, Merga H. Epidemiology of survival pattern and its predictors among HIV positive patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy in Southern Ethiopia public health facilities: a retrospective cohort study. AIDS Res Ther. 2020;17(1):49. doi:10.1186/s12981-020-00307-x

10. Lakoh S, Jiba DF, Kanu JE, et al. Causes of hospitalization and predictors of HIV-associated mortality at the main referral hospital in Sierra Leone: a prospective study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1320.

11. Ssempijja V, Namulema E, Ankunda R, et al. Temporal trends of early mortality and its risk factors in HIV-infected adults initiating antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;28:100600. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100600

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Fact Sheet: Today’s HIV/AIDS Epidemic. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016.

13. Digaffe T, Seyoum B, Oljirra L. Survival and predictors of mortality among adults on antiretroviral therapy in selected public Hospitals in Harar, Eastern Ethiopia. J Trop Dis. 2014;2(05):2. doi:10.4172/2329-891X.1000148

14. Johannessen A, Naman E, Ngowi BJ, et al. Predictors of mortality in HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy in a rural hospital in Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8(1):52. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-8-52

15. Tadele A, Shumey A, Hiruy N. Survival and predictors of mortality among adult patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy at debre-markos referral hospital, North West Ethiopia; a retrospective cohort study. J AIDS Clin Res. 2014;5(280):2.

16. Ababa A. Report on the 2014 Round Antenatal Care Based Sentinel HIV Surveillance in Ethiopia. Ethiop Public Heal Instititute; 2015.

17. Damtew B, Mengistie B, Alemayehu T. Survival and determinants of mortality in adult HIV/Aids patients initiating antiretroviral therapy in Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia. Pan African Med J. 2015;22(1). doi:10.11604/pamj.2015.22.138.4352

18. Tiruneh G, Getahun A, Adeba E. Assessing the impact of isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) on tuberculosis incidence and predictors of tuberculosis among adult patients enrolled on ART in Nekemte Town, Western Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2019;2019:1–8. doi:10.1155/2019/1413427

19. Ahmed A, Mekonnen D, Shiferaw AM, Belayneh F, Yenit MK. Incidence and determinants of tuberculosis infection among adult patients with HIV attending HIV care in north-east Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2):e016961. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016961

20. Setegn T, Takele A, Gizaw T, Nigatu D, Haile D. Predictors of mortality among adult antiretroviral therapy users in southeastern Ethiopia: retrospective cohort study. AIDS Res Treat. 2015;2015:1–8. doi:10.1155/2015/148769

21. Rao P, Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied survival analysis: regression modeling of time to event data. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95(450):681. doi:10.2307/2669422

22. Pandey A, Galvani AP. The global burden of HIV and prospects for control. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(12):e809–e11. doi:10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30230-9

23. Belay H, Alemseged F, Angesom T, Hintsa S, Abay M. Effect of late HIV diagnosis on HIV-related mortality among adults in general hospitals of Central Zone Tigray, northern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. Hiv/Aids (Auckland, NZ). 2017;9:187.

24. Tadesse K, Haile F, Hiruy N, Sued O. Predictors of mortality among patients enrolled on antiretroviral therapy in Aksum hospital, northern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e87392. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087392

25. Biadgilign S, Reda AA, Digaffe T. Predictors of mortality among HIV infected patients taking antiretroviral treatment in Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. AIDS Res Ther. 2012;9(1):15. doi:10.1186/1742-6405-9-15

26. Tsegaye AT, Alemu W, Ayele TA. Incidence and determinants of mortality among adult HIV infected patients on second-line antiretroviral treatment in Amhara region, Ethiopia: a retrospective follow up study. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;33. doi:10.11604/pamj.2019.33.89.16626

27. Joseph N, Sinha U, Tiwari N, Ghosh P, Sindhu P. Prognostic factors of mortality among adult patients on antiretroviral therapy in India: a hospital based retrospective cohort study. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1–10. doi:10.1155/2019/1419604

28. Kempton J, Hill A, Levi JA, Heath K, Pozniak A. Most new HIV infections, vertical transmissions and AIDS-related deaths occur in lower-prevalence countries. J Virus Erad. 2019;5(2):92–101. doi:10.1016/S2055-6640(20)30058-3

29. Ayele H, Van Mourik M, Bonten M. Predictors of adherence to isoniazid preventive therapy in people living with HIV in Ethiopia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2016;20(10):1342–1347. doi:10.5588/ijtld.15.0805

30. Mindachew M, Deribew A, Tessema F, Biadgilign S. Predictors of adherence to isoniazid preventive therapy among HIV positive adults in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):916. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-916

31. Agegnehu CD, Merid MW, Yenit MK. Incidence and predictors of virological failure among adult HIV patients on first-line antiretroviral therapy in Amhara regional referral hospitals; Ethiopia: a retrospective follow-up study. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):460. doi:10.1186/s12879-020-05177-2

32. Edessa D, Likisa J, Bellamy SL. A description of mortality associated with IPT plus ART compared to ART alone among HIV-infected individuals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137492–e. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0137492

33. Ayele HT, van Mourik MS, Bonten MJ. Effect of isoniazid preventive therapy on tuberculosis or death in persons with HIV: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):1–8. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-1089-3

34. Nyathi S, Dlodlo RA, Satyanarayana S, et al. Isoniazid preventive therapy: uptake, incidence of tuberculosis and survival among people living with HIV in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0223076. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0223076

35. Abuto W, Abera A, Gobena T, Dingeta T, Markos M. Survival and predictors of mortality among HIV positive adult patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy in public hospitals of Kambata Tambaro Zone, Southern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2021;13:271–281. doi:10.2147/HIV.S299219

36. Tachbele E, Ameni G. Survival and predictors of mortality among human immunodeficiency virus patients on anti-retroviral treatment at Jinka Hospital, South Omo, Ethiopia: a six years retrospective cohort study. Epidemiol Health. 2016;38. doi:10.4178/epih.e2016049

37. Muhula SO, Peter M, Sibhatu B, Meshack N, Lennie K. Effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the survival of HIV-infected adult patients in urban slums of Kenya. Pan African Med J. 2015;20(1). doi:10.11604/pamj.2015.20.63.4865

38. Bajpai R, Chaturvedi H, Jayaseelan L, et al. Effects of antiretroviral therapy on the survival of human immunodeficiency virus-positive adult patients in Andhra Pradesh, India: a retrospective cohort study, 2007–2013. J Prev Med Public Health. 2016;49(6):394. doi:10.3961/jpmph.16.073

39. Wisaksana R, Sumantri R, Indrati AR, et al. Anemia and iron homeostasis in a cohort of HIV-infected patients in Indonesia. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11(1):213. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-11-213

40. Santiago-Rodríguez EJ, Mayor AM, Fernández-Santos DM, Ruiz-Candelaria Y, Hunter-Mellado RF. Anemia in a cohort of HIV-infected Hispanics: prevalence, associated factors and impact on one-year mortality. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(1):439. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-439

41. Muyaya LM, Young T, Loveday M. Predictors of mortality in adults on treatment for human immunodeficiency virus-associated tuberculosis in Botswana: a retrospective cohort study. Medicine. 2018;97(16):e0486. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000010486

42. Enderis BO, Hebo SH, Debir MK, Sidamo NB, Shimber MS. Predictors of time to first line antiretroviral treatment failure among adult patients living with HIV in public health facilities of Arba Minch Town, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2019;29(2):175–186. doi:10.4314/ejhs.v29i2.4

43. Seyoum D, Degryse J-M, Kifle YG, et al. Risk factors for mortality among adult HIV/AIDS patients following antiretroviral therapy in Southwestern Ethiopia: an assessment through survival models. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(3):296. doi:10.3390/ijerph14030296

44. Rai S, Mahapatra B, Sircar S, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and its effect on survival of HIV-infected individuals in Jharkhand, India. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66860. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066860

45. Kang R, Luo L, Chen H, et al. Treatment outcomes of initial differential antiretroviral regimens among HIV patients in Southwest China: comparison from an observational cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e025666. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025666

46. Liu P, Liao L, Xu W, et al. Adherence, virological outcome, and drug resistance in Chinese HIV patients receiving first-line antiretroviral therapy from 2011 to 2015. Medicine. 2018;97(50):e13555. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000013555

47. Cavalcanti A, de Alencar Ximenes RA, Montarroyos UR, d’Albuquerque PM, Fonseca RA, de Barros Miranda-filho D. Effectiveness of four antiretroviral regimens for treating people living with HIV. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0239527. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0239527

48. Kiros M, Alemayehu DH, Geberekidan E, et al. Increased HIV-1 pretreatment drug resistance with consistent clade homogeneity among ART-naive HIV-1 infected individuals in Ethiopia. Retrovirology. 2020;17(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s12977-020-00542-0

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.