Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 7

Physician and medical student perceptions and expectations of the pediatric clerkship: a Qatar experience

Authors Hendaus M, Khan S, Osman S, Alsamman Y, Khanna T, Alhammadi A

Received 1 September 2015

Accepted for publication 11 November 2015

Published 19 May 2016 Volume 2016:7 Pages 287—292

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S95559

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Mohamed A Hendaus,1,2 Shabina Khan,1 Samar Osman,1 Yasser Alsamman,2 Tushar Khanna,2 Ahmed H Alhammadi1,2

1Department of Pediatrics, General Academic Pediatrics Division, Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, 2Weill Cornell Medical College-Qatar, Al Rayyan, Qatar

Background: The average number of clerkship weeks required for the pediatric core rotation by the US medical schools is significantly lower than those required for internal medicine or general surgery.

Objective: The objective behind conducting this survey study was to explore the perceptions and expectations of medical students and pediatric physicians about the third-year pediatric clerkship.

Methods: An anonymous survey questionnaire was distributed to all general pediatric physicians at Hamad Medical Corporation and to students from Weill Cornell Medical College-Qatar.

Results: Feedback was obtained from seven attending pediatricians (100% response rate), eight academic pediatric fellow physicians (100% response rate), 36 pediatric resident physicians (60% response rate), and 36 medical students (60% response rate). Qualitative and quantitative data values were expressed as frequencies along with percentages and mean ± standard deviation and median and range. A P-value <0.05 from a 2-tailed t-test was considered to be statistically significant. Participants from both sides agreed that medical students receive <4 hours per week of teaching, clinical rounds is the best environment for teaching, adequate bedside is provided, and that there is no adequate time for both groups to get acquainted to each other. On the other hand, respondents disagreed on the following topics: almost two-thirds of medical students perceive postgraduate year 1 and 2 pediatric residents as the best teachers, compared to 29.4% of physicians; 3 weeks of inpatient pediatric clerkship is enough for learning; the inpatient pediatric environment is safe and friendly; adequate feedback is provided by physicians to students; medical students have accessibility to physicians; students are encouraged to practice evidence-based medicine; and students get adequate exposure to multi-professional teams.

Conclusion: Assigning devoted physicians for education, providing proper job description or definition of the roles of medical student and physician in the pediatric team, providing more consistent feedback, and extending the duration of the pediatric clerkship can diminish the gap of perceptions and expectations between pediatric physicians and medical students.

Keywords: clerkship, perception, pediatric, teaching

Introduction

The average number of clerkship weeks required for the pediatric core rotation by the US medical schools is significantly lower than those required for internal medicine or general surgery.1 It is known that medical students’ attitudes toward their clerkship might have an impact on their future career choice.2 In addition, the education setting such as quality of teaching, structure of learning activities, and opportunities for clinical practice may influence the students’ perceptions of their learning and experiences during the pediatric core rotation.3

Moreover, it has been reported that medical students might encounter unpleasant experience when starting a clerkship; this is most likely attributed to their lack of knowledge of their specific roles in the new environment.4

The attending physician is the individual who provides care for his/her patients and is the one who is typically involved in the teaching of residents and medical students.5 However, pediatric academic departments face difficulties in recruiting enough teaching faculty to match the increased demand on direct observations and assessment of residents and medical students.6

The lack of adequate recruitment might lead to a situation where patient care and teaching are not adequate.5 Moreover, the literature has shown that the physician’s clinical proficiency and interpersonal communication skills can influence positively on medical students’ residency choice.3 It is worth mentioning that clinical setting (inpatient vs outpatient) plays a role in the students’ perceptions of learning.7

This study would be the first of its kind in Hamad General Hospital in the state of Qatar. Our pediatrics department clinical teaching ward serves as a teaching ground for third-year medical students of Weill Cornell Medical College-Qatar (WCMC-Q). The teaching responsibilities are shared between the attending physician, fellows, and residents.

Objective

The objective behind conducting this survey study was to explore the perceptions and expectations of medical students and pediatric physicians about the third-year pediatric clerkship at Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) in Qatar.

This study was designed to survey the quality of inpatient pediatric education provided to medical students taking into account the perceptions of all levels of teachers and students. It also aimed to identify the barriers to medical education unique to our setup, which is essential information to improve and standardize teaching.

Materials and methods

Study design, period, setting, and participants

The study was conducted at HMC, the only tertiary care, academic and teaching hospital in the state of Qatar, between October 1, 2013 and November 30, 2013. Our pediatric residency program is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education International (ACGME-I), and students from WCMC-Q rotate in our department as the primary site. The participants included academic general pediatric faculty, academic general pediatric clinical fellow physicians, pediatric resident physicians from all four postgraduate years (PGYs), and medical students. The four physicians and two medical students conducting this study were excluded from the study. A total of seven academic general pediatric faculties were targeted as well as eight academic general pediatric clinical fellows, 60 pediatric residents, and 60 medical students.

Survey instrument

A self-administered questionnaire was provided to all targeted participants. Questionnaires were distributed on-site at HMC during working hours, and participants were asked to return the questionnaire to a specified box. For medical students, we sent the questionnaires via e-mail with a link to monkey survey. The main reasons for using electronic surveys while surveying medical students were that the majority of them were in the US doing their fourth-year elective course and that there was a poor response rate if the physicians in HMC were asked to fill an online survey questionnaire. Each participant was asked to complete all sections of the questionnaire. There was no incentive for subjects to participate, and no reminders were supplied.

The questionnaire content was based on previous literature3,5,8–14 but adapted to Qatari’s system and modified for the purposes of our study. The biostatisticians in our medical research center validated the questionnaire. The survey was initially piloted to a small group of physicians and medical students.

The questionnaire was composed of 12 items. These sections addressed medical students and pediatric physicians of medical school pediatric inpatient clerkship. In addition, there was one demographic question for physicians.

Answers to questions regarding perception and expectation of pediatric physician and medical student about the third-year medical school pediatric clerkship were based on five-point Likert-style-graded response options, ranging from “strongly agreed” to “strongly disagreed” and “neutral”. Other response options included “excellent”, “adequate”, and “needs improvement”. The last question was an open-ended question for any comments. Verbal consent was obtained before administering the questionnaire, and participants were informed of why the information was being collected and how it would be used. Before the start of the interview, a statement was read to participants informing them that their participation was voluntary and confirmed that their answers would be anonymous and confidential. Approval for the study was obtained from HMC-Ethics Committee (Ref #13379/13).

Statistical analysis

Qualitative and quantitative data values were expressed as frequencies along with percentages and mean ± standard deviation and median and range. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic and all other characteristics of the participants. Associations between two or more qualitative or categorical variables were assessed using chi-square test. Mann–Whitney U test with correction was used for multiple comparisons. A P-value <0.05 from a 2-tailed t-test was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were done using statistical package SPSS, version 19.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Feedback was obtained from seven attending pediatricians (100% response rate), eight academic pediatric fellow physicians (100% response rate), 36 pediatric resident physicians (60% response rate), and 36 medical students (60% response rate).

Pediatric physicians and students reported that medical students receive <4 hours per week of teaching (80% of students vs 83% of physicians, P=0.271). There was a disagreement among the two groups in terms of who is the best teacher. Almost two-thirds of medical students perceived postgraduate year 1 and 2 pediatric residents as the best teachers, compared to 29.4% of physicians. In addition, 7% of students perceived that the senior residents provide the best teaching, compared to 33.3% of doctors. Furthermore, one-third of students voted for fellows vs one-quarter of physicians. None of the students believed that the attending consultant is the best teacher compared to 17.6% of the physicians (P=0.002).

Almost 45% of physicians and medical students believed that clinical rounds is the best environment for teaching. Only 9% felt that morning report is beneficial, and none of the medical students perceived the on-call time as a learning opportunity (P=0.002).

In terms of quality of bedside teaching, both parties agreed that it is adequate (45% of physicians vs 43% of students) but needs improvement (45% of both groups), while only one in ten of the overall participants agreed that it is excellent (P=0.975). Participants were also asked to rate the feedback provided by physicians to students, and the results were as follows: excellent, 10.2% of physicians vs 5.7% of students; adequate, 51% of physicians vs 68.6% of students; and needs improvement, 38.8% of physicians vs 25.7% of students (P=0.270). When it comes to adequate time for both groups to get acquainted to each other, 15% of both parties disagreed and strongly disagreed (P=0.016). More than 80% of physicians stated that a physician is easily accessible to medical students compared to 60% of students (P=0.321). One-third of students believed that we encourage them to practice evidence-based medicine, compared to 87.5% of the physicians (P=0.0001). Sixty percent of physicians thought that medical students are exposed to multi-professional team, but approximately only 30% of students echoed the same sentiment (P=0.012).

Three out of ten physicians (30%) disagreed and strongly disagreed that 3 weeks of inpatient pediatric clerkship is enough to learn pediatric medicine compared to 70% of the students (P=0.247). Sixty percent of doctors perceived that the inpatient pediatric environment is safe and friendly, and >90% of students agreed (P=0.0001).

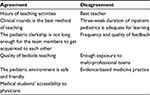

Tables 1 and 2 present a comparison of the two groups based on five-point Likert-style-graded response options. Agreement and disagreement are summarized in Table 3.

| Table 1 Physicians’ response (N=51) |

| Table 2 Medical students’ response (N=36) |

| Table 3 Points of agreement and disagreement between medical students and physicians |

Discussion

In the US, >90% of pediatric clerkships are based on the Council on Medical Student Education in Pediatrics curriculum. The pediatric clerkship emphasizes on growth and development, common clinical illness, prevention of disease, and health promotion.15 Our program is accredited by the ACGME-I, and therefore, we share similar curriculums with other nations.

This study shows that medical students and physicians have different perceptions of the third-year medical school pediatric clerkship, especially regarding the topics related to the best member of the team who can provide education, encouragement to practice evidence-based medicine, duration of the clerkship, and adequate exposure to multi-professional teams.

The pediatric inpatient rotation offers an opportunity to acquire knowledge and to enhance the thinking process of students and trainees. The medical students’ perception toward the pediatric clerkship educational experience is usually related to the attending physicians’ and residents’ attitudes.16,17

The inpatient pediatric clerkship provides a unique experience to medical students. Jospe et al found that students who were exposed to inpatient pediatrics seemed more likely to gear toward pediatrics as a career choice when compared to their peers who got only outpatient exposure.16

Medical students might encounter unpleasant experience when starting a clerkship.17 The difference in attitudes between the medical students and physicians is due to unpleasant experience or anxiety when starting a clerkship, especially if it is the first rotation of the third year. The literature echoes our belief.4

Proper shadowing of residents and friendly environment might ameliorate the anxiety and unpleasant experience of medical students and facilitate a smooth transition from medical school to residency.17,18

Teaching is well known as one of the main responsibilities of attending physicians who are assigned to care for patients in the general pediatric inpatient units.19 However, it is considered a difficult task to match a busy clinical service while simultaneously providing a good quality of teaching. Furthermore, nowadays medical education has been more structured and requires more dedicated time to provide timely feedback and to directly observe the skills of trainees.20

Medical students depend on residents in the diagnosis process; the reason could be that the clinical reasoning of residents is proximate to the students’ organization of education.3

In addition, resident physicians have been considered as crucial members of the educational team.21 Some studies found that faculty and residents are equally effective in providing medical education.22,23 Moreover, Gerbase et al studied the importance of residents in the health care system; they concluded that availability of residents in a program leads to a better evaluation of education by medical students.3

Studies have shown that proper orientation will allow medical students to understand the health care system.24 In addition, students value proper orientation in terms of their roles in the health care team such as how many patients they are expected to encounter, how much time they have to spend in every encounter, and what information should they present to the clinical teacher.25,26

It has been reported that bedside teaching has declined due to the physician’s or trainee’s attitude toward patient preferences, physician presentiment, and the system in the hospital.27

Almost one-half of our participants believe that bedside teaching needs improvement. We used this result as an incentive, and we created a new team that is dedicated only for teaching purposes including bedside. Our trainees including medical students perceive that the only feedback is the one received in paper at the end of the rotation. Hence, our institution provided a feedback workshop which assisted us in giving immediate oral feedback, and mid-rotation and end-of-rotation feedback to keep students in constant feedback environment.

Many studies focused on the student evaluation of the clinical teacher3 but did not touch on the specific items in our survey. Deliberate apprenticeship, which is defined as the mechanisms by which medical students gradually blend into a career by sharing activities with established professionals, is one of the crucial steps to establish an effective educational framework.28

Other important factors for building a successful educational curriculum are bidirectional or mutual evaluations by physicians and students,29 orientation to learning aspirations,28 creation of job descriptions, and focus on medical student education.5

With the unique opportunity and challenges that the pediatric inpatient setup offers, it is imperative that each institution analyze and standardize their teaching structure for medical students in the inpatient setting so that it becomes a productive and rewarding experience for both the preceptor and the student.

Limitations

There are few limitations in this study. The results are restricted to the item in the survey and might not be comprehensive. In addition, the sample size might not be large enough. Moreover, we did not render formal definitions to the items in the survey, and therefore, individual perception might have affected the results. However, our data is a reflection of many programs around the globe, since our program is accredited by the ACGME-I.

Conclusion

Appreciable variations occur between pediatric physicians and medical students with respect to their perceptions and expectations of medical student education. Pediatric inpatient rotation offers an opportunity to acquire knowledge and to enhance the thinking process of students and trainees. Assigning devoted physicians for education, providing proper job description or definition of the roles of medical student and physician in the pediatric team, providing more consistent feedback, and extending the duration of the pediatric clerkship can diminish the gap of perceptions and expectation between pediatric physicians and medical students. Our findings will assist in the design and implementation of different models for managing the learning experience in the wards.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the medical research center in HMC for their support and ethical approval.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Kies SM, Roth V, Rowland M. Association of third-year medical students’ first clerkship with overall clerkship performance and examination scores. JAMA. 2010;304(11):1220–1226. | ||

Ekenze SO, Obi UM. Perception of undergraduate pediatric surgery clerkship in a developing country. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(4):560–566. | ||

Gerbase MW, Germond M, Nendaz MR, Vu NV. When the evaluated becomes evaluator: what can we learn from students’ experiences during clerkships? Acad Med. 2009;84(7):877–885. | ||

Poncelet A, O’Brien B. Preparing medical students for clerkships: a descriptive analysis of transition courses. Acad Med. 2008;83:444–450. | ||

Barone MA, Dudas RA, Stewart RW, Mcmillan JA, Dover GJ, Serwint JR. Improving teaching on an inpatient pediatrics service: a retrospective analysis of a program change. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:92. | ||

Functions and structure of a medical school. Standards for accreditation of medical education programs leading to the M.D. degree. 2014. Available from: https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/LCME%20Standards%20May%202012.pdf. Accessed May 9, 2014. | ||

Beckman TJ, Ghosh AK, Cook DA, Erwin PJ, Mandrekar JN. How reliable are assessments of clinical teaching? A review of the published instruments. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:971–977. | ||

Cassidy-Smith TN, Kilgannon JH, Nyce AL, Chansky ME, Baumann BM. Impact of a teaching attending physician on medical student, resident, and faculty perceptions and satisfaction. CJEM. 2011;13(4):259–266. | ||

De SK, Henke PK, Ailawadi G, Dimick JB, Colletti LM. Attending, house officer, and medical student perceptions about teaching in the third-year medical school general surgery clerkship. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199(6):932–942. | ||

Hendry RG, Kawai GK, Moody WE, et al. Consultant attitudes to undertaking undergraduate teaching duties: perspectives from hospitals serving a large medical school. Med Educ. 2005;39(11):1129–1139. | ||

Macdonald J. A survey of staff attitudes to increasing medical undergraduate education in a district general hospital. Med Educ. 2005;39(7):688–695. | ||

O’Brien B, Cooke M, Irby DM. Perceptions and attributions of third-year student struggles in clerkships: do students and clerkship directors agree? Acad Med. 2007;82(10):970–978. | ||

Stark P. Teaching and learning in the clinical setting: a qualitative study of the perceptions of students and teachers. Med Educ. 2003;37(11):975–982. | ||

Wenrich M, Jackson MB, Scherpbier AJ, Wolfhagen IH, Ramsey PG, Goldstein EA. Ready or not? Expectations of faculty and medical students for clinical skills preparation for clerkships. Med Educ Online. 2010;15. Available from: http://med-ed-online.net/index.php/meo/article/view/5295. Accessed May 4, 2016. | ||

Third year curriculum. Council on Medical Student Education in Pediatrics. Available from: https://www.comsep.org/educationalresources/currthirdyear.cfm. Accessed May 9, 2015. | ||

Jospe N, Kaplowitz PB, McCurdy FA, Gottlieb RP, Harris MA, Boyle R. Third year medical student survey of office perceptorships during the pediatric clerkship. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(5):592–596. | ||

Berridge E, Freeth D, Sharpe J, Robert CM. Bridging the gap: supporting the transition from medical student to practising doctor—a two-week preparation programme after graduation. Med Teach. 2007;29:119–127. | ||

Jones A, Willis S, Mcardle P, O’Neill PA. Learning the house office role: reflections on the value of shadowing a PRHO. Med Teach. 2006;28:291–293. | ||

Greganti MA, Drossman DA, Rogers JF. The role of the attending physician. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142(4):698–699. | ||

Andreae MC, Freed GL. Using a productivity-based physician compensation program at an academic health center: a case study. Acad Med. 2002;77(9):894–899. | ||

Irby DM. Where have all the preceptors gone? Erosion of the volunteer clinical faculty. West J Med. 2001;174:246. | ||

Scheiner JD, Mainiero MB. Effectiveness and student perceptions of standardized radiology clerkship lectures: a comparison between resident and attending radiologist performances. Acad Radiol. 2003;10:87–90. | ||

Cooper DD, Wilson AB, Huffman GN, Humbert AJ. Medical students’ perception of residents as teachers: comparing effectiveness of residents and faculty during simulation debriefings. J Grad Med Educ. 2012; 4(4):486–489. | ||

Raszka WV, Maloney CG, Hanson JL. Getting off to a good start: discussing goals and expectations with medical students. Pediatrics. 2010;126:193–195. | ||

Jacobs JC, Van Luijk SJ, Van Berkel H, Van der Vleuten CP, Croiset G, Scheele F. Development of an instrument (the COLT) to measure conceptions on learning and teaching of teachers, in student centered medical education. Med Teach. 2012;34:e483–e491. | ||

Hunter A, Desai S, Harrison R, Chan BK. Medical student evaluation of the quality of hospitalist and nonhospitalist teaching faculty on the inpatient medicine rotations. Acad Med. 2004;79:78–82. | ||

Gonzalo JD, Masters PA, Simons RJ, Chuang CH. Attending rounds and bedside case presentations: medical student and medicine resident experiences and attitudes. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):105–110. | ||

Iyer MS, Mullan PB, Santen, SA, Sikavitsas A, Christner JG. Deliberate apprenticeship in the pediatric emergency department improves experience for third-year students. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(4):424–429. | ||

Beckman TJ, Mandrekar JN. The interpersonal, cognitive and efficiency domains of clinical teaching: construct validity of a multi-dimensional scale. Med Educ. 2005;39:1221–1229. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.