Back to Journals » International Journal of General Medicine » Volume 9

Pharmacist-led minor ailment programs: a Canadian perspective

Received 18 May 2016

Accepted for publication 11 June 2016

Published 10 August 2016 Volume 2016:9 Pages 291—302

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S99540

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Jeff Gordon Taylor,1 Ray Joubert,2

1College of Pharmacy and Nutrition, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, 2Saskatchewan College of Pharmacy Professionals, Regina, SK, Canada

Abstract: Pharmacists have a long history of helping Canadians with minor ailments. This often has involved management with over-the-counter medications. If pharmacists felt that the best care required something more robust, they would refer the patient to a physician. In hopes of improving the care of such ailments, Canadian provinces have granted pharmacists the option of selecting medications traditionally under physician control. This review examines the Canadian perspective on pharmacists prescribing for minor ailments and the evidence of value for these programs. It might provide guidance for other jurisdictions contemplating such a move.

Keywords: minor ailments, pharmacist prescribing, Canada, over-the-counter medications

Background

Canada’s health care system is publicly funded, with universal coverage for its citizens. Patients do not pay for hospital stays, most diagnostic tests, or most of the services from their family physician. There is no national plan to cover drug costs, but provinces do have coverage in place for certain groups, such as seniors and those with low incomes.

In 2013, family physicians billed their provincial health department an average of CA$43.72 per service.1 For a scenario involving (for example) a patient worried about urinary frequency and burning, a visit to the physician could result in a urine sample. The physician receives a basic fee of approximately $32, the lab cost for the culture report is $30, and the cost of medicine is approximately $15 (some or all being the responsibility of the patient).2

In 2015, it was estimated that total health expenditure reached $219 billion (or $6,105 per person), representing 10.9% of gross domestic product.3 As with most modern countries, there is considerable worry about the escalating costs of this care. In 2016, there were 80,544 physicians (240 per 100,000 people).4 Just over half are family physicians. Canada’s physician to population ratio ranks 28th of 34 OECD nations.

Waiting times and actual access to a family physician continue to be a concern. In 2013, 15.5% of Canadians (approximately 4.6 million people) reported they did not have a regular physician.5 There are regional disparities on this front: less than 10% of physicians practice in rural areas, whereas 19% of Canadians live in rural areas.4

That said, of those without a family physician, 81% reported still having options when they were sick: 59% reported using a walk-in clinic, 13% visited an emergency room, 9% used a community health center, and some chose telephone health lines to get advice.5 Among those who had looked for a physician, 25% stated there was none available in their area. While there are medical clinics in places like Walmart, the rise of retail clinics (for such conditions as otitis media, pharyngitis, and urinary tract infections), as seen in the US,6 has not materialized.

Over-the-counter medication in Canada

When a person acquires a minor ailment, s/he can either take a wait-and-see approach, use an over-the-counter (OTC) medication (an out-of-pocket expense), ask a pharmacist for advice (no charge), or seek medical care (which would be covered by health insurance). While garnering far less attention than such conditions as diabetes and hypertension, minor ailments have a huge impact on the health care system. Managing such illnesses without medical intervention is important to a properly functioning system. If Canadians decided to seek medical or pharmacist care for even a slightly greater percentage of cases, it would raise health care costs considerably.

The majority of OTC medications are sold from pharmacies in Canada. In 2014, domestic retail sales of consumer health products were valued at $5.6 billion.7 Medications sold in Canada require either a prescription or are available OTC. When relegated to OTC status, legislation dictates whether the agent requires pharmacist assistance during the sale or whether the agent can be sold from nonpharmacy retail outlets.

Agents that have OTC status in Canada might be prescriptive in other countries and vice versa. For instance, second-generation antihistamines were available OTC in Canada years before the US. Conversely, only recently was topical hydrocortisone 1% made available to consumers, decades after the US. A topical antibiotic-combination product is available without prescription for bacterial conjunctivitis, all nicotine-replacement products are OTC, as are vaginal antifungal agents (oral and topical), while the first OTC topical intranasal steroid just appeared in the past year. Some agents with OTC status still require a pharmacist to be involved in their sale (many cough/cold products, iron preparations, and topical antibiotics for skin conditions, for example).

Pharmacist involvement in OTC-medication sales

Canada has approximately 39,000 licensed pharmacists. Of those, approximately 27,500 work in the 9,600 community pharmacies across the country.8 Most (87.4%) employers of pharmacists are located in urban areas, with 12.6% located in rural areas.9

Pharmacists have at least a 100-year history as purveyors of OTC medications in Canada. While a lot of transactions do not involve pharmacists, many others do.10 In 1996, an attempt was made at quantifying the extent and value of such activity. During a 2-week period, approximately 500 pharmacies from across the country recorded all instances where they gave advice on OTC products.11 Extending the data to a national level and per annum basis, the 6,121 pharmacies at the time would have made nearly 15 million OTC interventions. These numbers could have been higher: there was the possibility that only half of eligible interventions were actually reported. If 25% of the recorded encounters chose to seek a physician instead, it would have meant an extra $169 million in physician billing.

Pharmacist prescribing

Pharmacist prescribing for minor ailments is a relatively new initiative in Canada. In 2007, Alberta became the first province to allow pharmacists to prescribe medications, but their legislation went far beyond just minor ailments. All the remaining provinces have since adopted (or are currently pursuing) various degrees of prescriptive authority.12 Pharmacists now have the option of selecting medications from a limited formulary, ones traditionally under the sole control of physicians. An example scenario would be a topical antifungal for a diaper rash or a topical retinoid/antibiotic for a patient with acne.

Nova Scotia was one of the first to add minor ailments as an expanded aspect of practice in January 2011. New legislation soon thereafter enabled Saskatchewan pharmacists to do the same. As of February 2012, this province became the first government in Canada to pay for minor-ailment prescribing ($18 per case).

There is no overarching national initiative for such programs; each province is left to its own accord. As such, the conditions covered vary, as will the political interest and timelines for program implementation. For programs already in place, the applicable conditions appear in Table 1.

| Table 1 Conditions covered within provincial minor-ailment programs Abbreviations: GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; UTI, urinary tract infection. |

Need for the service

The impetus for adding prescribing powers is a need for less expensive, yet effective care. However, one should ask: Who is making this argument, and how justifiable is it?

Medical care for minor ailments is expensive, and all provincial governments would surely be aware of that fact. However, public service announcements to encourage self-care among the public do not exist. There is no national campaign to promote self-care for minor ailments, but it is also highly likely that provincial health departments would welcome discussions of any new ways to lower health care costs. Accordingly, it has been pharmacy organizations that have lobbied government offices on the potential benefits of pharmacist prescribing for minor ailments.

Access to medical care is an issue for many citizens, be it actually having a family physician or the amount of effort needed to see one in a timely fashion. When pharmacist prescribing was adopted in one province, the health minister stated, “We think it makes good sense. It will alleviate waits at doctors’ offices and even emergency rooms”.13 In a lot of rural settings, a case could be made that pharmacies have more presence than physicians. Therefore, the pharmacist becomes a logical choice of many for minor-ailment care, a fact supported by a long history of involvement.

However, easier access to one health care provider does not necessarily mean that that is the solution to a complex issue. Perhaps the answer is simply more physicians. Given that physicians will likely know the patient’s full history better than other health care providers, and can physically examine the patient, this may be ideal (albeit expensive) care. While minor ailments do not require medical attention by definition, research has also found they can be far more complex than trivial, inappropriate, or unnecessary consultations that waste the time of the physician.14

Several health systems (primarily in the UK) have been encouraging the public to consider pharmacists as a first port of call for minor ailments.15–20 In Canada, with the programs now in place, provincial pharmacy bodies have taken up the marketing to the public. Patients themselves consider pharmacies a logical place to start the care process.11,21–23 It must also be noted that the public tends to self-medicate minor ailments before seeing any health care provider.23–27 For example, for patients with respiratory tract infections, 55.4% self-medicated before medical consultation and 21.5% did so after consultation.28 This will of course vary with the nature of the illness.29–33

When care is sought, physicians and pharmacists are key sources. Physicians are seen as a first choice by many.31,34–37 Researchers found that of 1,521 people seeking help from physicians for a minor ailment, only 38% opted for pharmacist care when offered the option.38 In other reports, it is the pharmacist who would first be approached.39–43 UK mothers have noted they would consult with pharmacists if their children had coughs, colds, aches, and pains, but turn to their physician for childhood fever, sickness, diarrhea, and rashes.44 In other British work, those visiting a pharmacy felt their symptoms were not serious enough to consult a physician, while those visiting a GP felt their symptoms were not serious enough for the emergency department.19 Canadians have stated they do not like to bother physicians for minor ailments.37

A rarely mentioned argument for pharmacist involvement in minor ailments is the impact it could have on so-called treatment gaps. As already suggested, a sizable proportion of cases do not receive medical care. Only 1% of Canadians reported seeing a physician for their last cold.45 However, that level of physician involvement, for that specific condition, is likely the appropriate amount of utilization. For other conditions, patients would be better served by more medical attention, rather than settling for potentially less effective OTC therapy.46,47 Such situations can be described as having a treatment gap: the difference between those who likely qualify for a certain agent versus the percentage of patients who are actually using that same agent. These gaps are often created simply by patients choosing not to seek medical intervention, leading to suboptimal care. Gaps have been noted for allergic rhinitis,48 migraine headaches,49 allergic conjunctivitis,50,51 acne,52 and overactive bladder.53 More allergy sufferers, for example, should be using topical intranasal steroids than the number that currently do. By initiating therapies, which may not have otherwise been considered by patients (nor previously available to pharmacists), patient quality of life should improve. Under pharmacist-prescribing guidelines, patients are eventually referred on to physicians for continuing care if the condition is chronic in nature.

Any additional pharmacist involvement should be balanced by any negative impact of prescribing. For example, medical oversight will be needed in cases where pharmacists have made mistakes and/or have caused delays in care. The level at which that this occurs in Canada is not well known. However, there is information on reconsultation rates (physician, then another physician) for minor ailments seen by family physicians, walk-in clinics, and emergency departments.54 Reconsultation rates (pharmacist then physician) have been documented for the UK, with a range of 2.4%–23.4% in a report published to 2013.55 In the Care at the Chemist study, 33 of 576 patients reconsulted for the same minor condition within 14 days.16 Watson et al recently found that reconsultation rates involving four minor ailments seen at emergency departments, medical clinics, and pharmacies were quite similar.19

The prescribing powers granted to pharmacists in Canada parallel other activity in the country. Nurses and optometrists are also gaining new authority. For example, many provinces now allow optometrists to diagnose, treat, and manage glaucoma, including prescribing oral medications. The situations in three provinces are now outlined, chosen to reflect the broad state of affairs in the country. Saskatchewan draws greater attention, since its program is more established and most of the evaluative work to date emanates from that province.

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotian pharmacists were among the first in the nation to obtain prescribing authority for minor ailments. A total of 31 ailments are covered under the program, including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), cold sores, and emergency contraception. For any encounter, pharmacists are to conduct a detailed assessment, make a prescribing decision, establish a plan for follow-up (as needed), and then notify the primary care provider if a prescription was written. Once follow-up is complete, pharmacies were reimbursed $22.50 during a pilot. The program received financial support from a national pharmacy chain to enable this. Patients did not incur any cost for the service.

For this pilot, pharmacists received training sessions on minor ailments. Then, the provincial pharmacy association contracted a firm to evaluate the service independently. A total of 27 pharmacies participated over a 3-month-long period in 2013, during which 1,002 patients received care.

The most common ailments dealt with were cold sores (17%) and allergic rhinitis (15%).56 With regard to interaction dynamics, about an even number of patients asked for assistance in the pharmacy as offers of help from pharmacists. Pharmacists who had spoken with physicians during the care process said they were mostly supportive of the program.

In many cases involving minor ailments in pharmacies, the actual patient may not be present. Parents often raise concerns for children, for example. As such, a pharmacist may not be able to see a skin rash or hear a cough firsthand. The standards of practice for Nova Scotia addressed this issue. When a pharmacist is not able to see the patient, four provisos must be met:57

- the pharmacist has personally seen the patient in the past, and has an established relationship

- the pharmacist has previously seen and assessed the patient for the same condition, or the patient had been diagnosed by a physician (and that assessment remains current)

- the pharmacist has knowledge of the patient’s condition and current clinical status

- the pharmacist communicates the decision to the patient’s agent.

Of the 1,002 patients, 587 (59%) went on to complete satisfaction surveys. Most (89%) saw satisfactory resolution of symptoms. Patient feedback indicated that being able to access health care sooner was a benefit. Cost was seen as an eventual barrier for some patients if the program continued into the future, with a third indicating they would not pay for such a service if it was not covered by the health department or private insurance. Of those willing to pay out of pocket, the average amount was $18.95 (based on 359 responses).

If the service had not been available, patients indicated they would have either seen their family physician (57%) or sought help at a walk-in clinic (20%), while 9% would have gone to an emergency department. Ten percent would not have sought help. Recently (April 2015), the provincial health department agreed to pay pharmacies $20 for three categories of minor ailments off the initial list (cold sores, runny noses, and skin conditions).58

Ontario

In Ontario, pharmacy researchers went to stakeholders and examined policy documents for perspectives on prescriptive authority (minor ailments and beyond) for pharmacists.59 A total of 51 documents were deemed to have relevance, while 17 key informants were identified for semistructured interviews. Pharmacy organizations and Ontario government representatives both expressed support for prescriptive authority. However, medical organizations were opposed to this expanded role, citing a lack of training and experience in diagnosis and prescribing as potential threats to patient safety. A citizen brief produced by McMaster University concluded there was evidence that pharmacy-based minor ailments were suitable alternatives to primary care consultations.60

A 2013 report commissioned by the Ontario Pharmacists Association estimated that introducing a program involving nine minor ailments could save the province $12.3 million over 5 years.61 Another report from the pharmacy association garnered input from over 200 members in 2014, with approximately 90% showing support for expanding pharmacy services to include a common-ailment program.62 Three-quarters felt prepared to take on the duties required of assessing and treating common ailments. Cold sores, allergic rhinitis, and canker sores garnered the most support (over 90%), while migraines (62.1%), bacterial skin infections (62.9%), and dysmenorrhea (66.4%) saw the least support. A minor-ailment prescribing program has yet to materialize in the province.

Saskatchewan

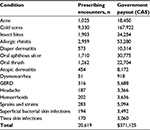

Saskatchewan’s program now encompasses 17 ailments. A decision was made to adopt new conditions slowly, starting with three, then seven, then the current 17. Between February 2012 and December 2014, 20,619 prescribing encounters took place (Table 2), for a total outlay of $371,125 in government payments.63

| Table 2 Minor ailment transactions involving prescribed agents (February 2012 to December 2014) Note: Reproduced with permission from the Pharmacy Association of Saskatchewan.63 Abbreviation: GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. |

The Saskatchewan prescribing guidelines for minor ailments are based on an important tenet: that of a patient’s self-diagnosis. Patients, it would seem, might be expected to articulate the ailment they feel they have during such consults, be it acne or allergic rhinitis. According to the guidelines and as part of the assessment process, if a pharmacist is unable to confirm the patient’s self-diagnosis, then that patient is to refer to a physician.

One may ask: Why not have pharmacists undertake this important task, thereby increasing the chances of it being done correctly? The reason was that it was argued by physicians during program development that pharmacists cannot diagnose, an issue that continues to be problematic for their profession.64 Avoiding the concern over pharmacists diagnosing resulted in an exercise in carefully crafted terminology. A position was eventually taken that if a patient entered an encounter by stating “I have a rash and blisters between my toes on one foot” and a pharmacist concluded his/her assessment with an official diagnosis (“athlete’s foot”), then that would go beyond a pharmacist’s scope of practice. Alternatively, if the patient were to come and say “I have athlete’s foot”, then a pharmacist would bypass any legalities by simply engaging in the usual questions and observations to confirm that self-diagnosis.

Whether patients actually mention their own diagnosis during such pharmacy encounters or simply present a shopping list of bothersome symptoms is likely so nebulous during actual events that no one would know how often either route occurs.65 It should not matter either way, given that an appropriate clinical recommendation by the pharmacist can be provided irrespective of which path is taken. While the ability of the public to self-diagnose will be suspect in some areas, stronger in others, pharmacist appraisal of that self-assessment will either support or override any conclusions they have drawn.

Pharmacists received mandatory training (∼3 hours) for the first three conditions. Thereafter, it was up to individual pharmacists to decide whether they needed optional updating for any given condition. The governing pharmacy body made resources available for this purpose. Continuing-education units are also required of pharmacists on a yearly basis, but that requirement is broad in nature (rather than specific solely to minor ailments).

To parallel practice, minor ailment prescribing is now part of the emphasis of training for pharmacy students at the University of Saskatchewan. Students receive approximately 3 hours on the prescribing process during undergraduate work. For minor ailments in general, the college dedicates approximately 90 hours of didactic time, 16 hours of tutorials, and 10 hours of practice-lab exposure. Students are to apply that education during 1-month clinical rotations for two summers (under supervision) before graduation.

Minor-ailment prescribing encounters in pharmacies typically occur via two paths. In one, a patient will have heard of the new service being offered by pharmacists. They will likely have tried various OTC medications, but now want something more effective, which they heard pharmacists can take care of. Some may even have had the agent previously prescribed by a physician, but now choose a pharmacist for the help. To be paid ($18), pharmacists submit an electronic claim to the provincial drug plan for the service rendered.

For the second path, the patient is completely unaware of the new service. The person simply presents to the pharmacist in search of symptom relief. In the course of assessing the patient, the pharmacist determines that the next best step would be a medication for which they can now prescribe. Rather than medical referral for an inhaled nasal steroid for allergies or a topical antibiotic for acne, the pharmacist now initiates therapy. Generally, referral is still needed if two trial prescriptions fail to produce improvement (eg, triptans for headaches, topical agents for acne) or symptoms are not resolved within a reasonable time frame (eg, 7 days for cold sores).66 Prescribing guidelines have been created via contract work with a provincial drug-information service and various committees (with physician input).

Steps taken during program implementation

The birth of the program began in 2000, when the provincial pharmacy registrar met with a local obstetrician, who off-handedly noted after a meeting: “Why aren’t you guys allowing pharmacists to prescribe emergency contraception like in BC and Washington?” The registrar saw merit in the idea. Subsequent efforts led to the creation of a discussion paper on amendments to the provincial pharmacy act, authorizing pharmacists to prescribe emergency contraception, but also to adapt prescriptions (extend refills, emergency fills). Similar events were occurring in other provinces. Consultations began with the professions of medicine and nursing, with efforts resulting in general support for the concept. In 2003, amendments were made to the governance of prescribing of drugs by pharmacists. However, the new regulations authorized pharmacist prescribing only for emergency contraception. According to the Ministry of Health, prescription adaptations were placed on hold, because the health system was not ready for this role of the pharmacist.

Also in 2003, the pharmacy registrar joined a fact-finding tour of primary care sites in the UK. There, he serendipitously met a pharmacist practicing in a deprived area of Glasgow, who explained the proposed UK Minor Ailment Service. One of that pharmacist’s patients had challenges accessing primary care for her common ailments because she was homeless. The pharmacist exclaimed that she wished she had the authority to prescribe antifungal agents to treat that patient’s toenail infection. This was a defining moment in conceptualizing minor-ailment prescribing for Saskatchewan. The registrar began laying the groundwork for the service.

Events in other provinces, in particular prescriptive authority in Alberta, stimulated Saskatchewan authorities to develop a policy paper. The pharmacy regulatory association released a consultation paper in 2006. They formed an interdisciplinary advisory committee on prescriptive authority consisting of representatives from the professions involved in prescribing drugs (medicine, nursing, dentistry, optometry), with representation from the provincial college of pharmacy, community and hospital pharmacists, and the Ministry of Health. The committee’s mandate was to advise on policy governing the prescribing of drugs by pharmacists. After several meetings, a policy was approved, and a position statement was released in 2008. Among a number of concepts, it outlined prescribing prescription drugs officially indicated for minor or self-limiting ailments.

Work began on a list of relevant conditions. The first set was derived in 2009 and then submitted to the Ministry of Health for approval. Further consultations took place with pharmacists, advisory committee meetings, and physician and nursing officials. The Ministry of Health held their own consultations on the subject. New bylaws enabling this service were officially approved by the province in 2011.

The provincial drug information service was contracted to develop prescribing guidelines. That body conducted a literature review, held pharmacist focus groups, and developed drafts for expert reviews (done by both pharmacists and physicians). The guidelines specified the following criteria for minor-ailment conditions:

- can be reliably self-diagnosed by patient

- self-limiting condition

- laboratory tests not required for diagnosis

- treatment will not mask underlying conditions

- medical and medication histories can reliably differentiate more serious conditions

- only minimal or short-term follow-up needed.

The guidelines also specified the following criteria for prescription drugs suitable for pharmacist prescribing in such circumstances:

- having an official indication for the self-care condition

- having valid evidence of efficacy for the self-care condition

- having a wide safety margin

- not subject to abuse

- dosage regimen for treatment of self-care conditions is not complicated.

Prior to program implementation, the province’s continuing professional development unit developed training sessions. Training began in 2011, and it was mandatory for pharmacists who wanted to prescribe for minor ailments. The first three conditions were: cold sores, mild acne, and insect bites. In 2012, pharmacists began to be paid an assessment fee for minor-ailment consultations. Other conditions were added to the payment schedule in 2012, then again in 2014.

Throughout this process, provincial medical authorities continued to raise concerns, especially from such specialists as dermatologists. One issue was that of the reliability of patient self-diagnosis. Another was that compensation for prescribing creates a conflict of interest contrary to the public interest. Specifically, physicians are not allowed to diagnose and prescribe, and thus pharmacists should be held to the same standard. Physicians strongly encouraged a phasing in of the program, starting with the least controversial conditions, and then only to expand (or contract) the number of conditions depending on experience gained. Of a broad list initially presented to physicians, medicine responded accordingly: 1) implement now – mild acne, cold sores, insect bites; 2) needs further review – allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, oral aphthous ulcers, diaper dermatitis, tinea infections, musculoskeletal pain, stiffness, spasm, oral thrush, superficial bacterial skin infections; and 3) stop/reconsider – dysmenorrhea, GERD, hemorrhoids. Some of the concerns have never been fully resolved.

Program evaluation – patient feedback

As alluded to, there is significant concern in medical circles whether pharmacist-directed care will be of an appropriate standard. To assess any program comprehensively, an approach would have to determine whether it were cost-effective (for pharmacists and society), whether appropriate clinical outcomes were being met, whether the right patients were using the service, whether users were satisfied, the impact on physician workload, and whether the program paperwork were practical/realistic for pharmacists.

Clinical outcome was the focus of the first attempt at evaluation.67 Done in 2013, 125 patients provided feedback. Unfortunately, this was only a fraction of the transactions that took place in the province to that point, making any conclusions weak. For perspective, 5,542 minor-ailment prescriptions took place from the program’s start to June 2013.

The conditions under pharmacist-led care significantly or completely improved in 81% of cases. However, one must note that many minor ailments are by definition self-limiting and can obviously get better on their own. Only 4% experienced bothersome side effects with the agents initiated by pharmacists. With regard to assessment of their case, only 6% of patients felt a physician would have been more thorough. Approximately one-quarter would have chosen to go to a physician or emergency department had the minor ailment service not been available, an important consideration when considering the economic value of the program. Satisfaction with the pharmacist and with the service was high. Trust in pharmacists and convenience were the most common reasons for choosing a pharmacist over a physician.

Assessment of clinical outcomes restarted in 2015, with more conditions now under the program’s scope [Taylor, unpublished data, 2016]. Again, patient uptake was extremely low: only 50 patients had participated at the 1-year point. A partial explanation for this was that 50% less pharmacists were sending patients to this study compared to the first phase.

Symptom resolution and satisfaction with the service was again high. New questions were added during this phase, to get perspective on patient illness behavior relative to minor ailments. Seventy-five percent of patients were quite sure of what condition they had before going to the pharmacy. A similar percentage was confident in knowing when to go to a physician for care rather than a pharmacist. This suggests that the public feels they opt for pharmacist-led care appropriately.

Program evaluation – pharmacist feedback

During the summer of 2015, pharmacist feedback was sought. Instead of looking at how the program operates from the pharmacist’s perspective (ease of use, paperwork needed, staffing requirements, etc), an opportunity was taken to compare/contrast pharmacist impressions of minor-ailment care to those of physicians.68 Approximately 300 pharmacists were involved in this mail survey. The program covered 17 minor ailments at the time.

The vast majority of pharmacists had prescribed 20 times or fewer. Minor-ailment visits can start with the patient describing their symptoms (“I am here because my stomach hurts”) or conversely by stating a self-diagnosis (“I think I have condition X”). Pharmacists estimated that at least half the patients articulate a self-diagnosis during such encounters, a key directive of the guidelines. As a gauge of the public’s ability to make this assessment, an estimated 10% of encounters turn out to be something more serious than what the patient originally suspected.

Pharmacies are a common choice of many for minor ailments, but another health care provider may have been a better option. Estimates were garnered from pharmacists on the percentage of cases initially seen in pharmacies, but should not be handled by pharmacists. In other words, these would be cases where the patient likely underestimated the severity/complexity of their situation. Broadly speaking, less than 10% of all cold sore cases are generally referred to a physician, while one-third of pharmacists refer bacterial conjunctivitis cases almost all the time. Migraines had one of the highest levels of referral to medical care.

This suggests that minor ailments presenting in pharmacies are likely on the low end of severity. Further, pharmacists appear to be well aware of the potential complexity of certain ailments covered under the program. As seen later with physician feedback, pharmacists share the very same level of concern for several ailments. The majority of pharmacists felt that between 10% and 30% of the minor ailments, initially handled by pharmacists, would need medical care relatively soon for that same problem (a glimpse at reconsultation rates). Responders were supportive of the clinical guidelines available online for prescribing.

Program evaluation – physician feedback

During the same summer, physicians were given a survey with many of the same questions asked of pharmacists. Results were based on information provided by 289 responders.64 The majority estimated 10%–30% of their medical appointments were primarily for minor ailments. Most wanted to see patients about a so-called minor ailment rather than miss something critical. Physicians indicated that a sizable portion of these visits had patients mention a self-diagnosis. Most encounters did not turn out to be something more serious, a similar finding in the pharmacist survey.

There was not strong support for patients seeing a pharmacist first for a minor ailment. Many doubted that pharmacists had the training to diagnose or triage such ailments, handicapped by the inability to perform a physical examination. There was also strong concern with pharmacists diagnosing a condition, then prescribing an agent, a situation they are not allowed to do for ethical reasons.

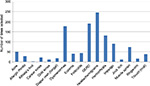

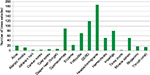

From a list of conditions relevant to pharmacist prescribing, physicians identified headache/migraine, dysmenorrhea, GERD, and hemorrhoids to be of most concern regarding patient safety (Figure 1). It is important to note that pharmacists held the very same concerns during their own dealings with these conditions, likely indicative of a cautious approach to minor-ailment management (Figure 2). Cold sores and athlete’s foot were of least concern to physicians. Physicians were undecided as to what the demand level was for this service.

| Figure 1 Conditions of most concern to physicians. Note: Reproduced with permission from the SelfCare journal.64 Abbreviation: GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. |

| Figure 2 Conditions of most concern to pharmacists. Note: Reproduced with permission from the SelfCare journal.68 Abbreviation: GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. |

Whether pharmacist prescribing for minor ailments will reduce health care costs, 150 responders were either unsure or agreed it would save dollars. Conversely, 135 responders disagreed with this notion. Those disagreeing were then asked to provide reasons for that position, with the responses evenly split between 1) physician care will be needed to fix pharmacist oversight, 2) it will lead to pharmacists and physicians billing the government for the same ailment, and 3) minor ailments that are often mild are now needlessly treated.

Approximately one-third of physicians estimated that 10%–30% of minor ailments initially handled by pharmacists would need medical care relatively soon thereafter for that same problem (reconsultation rate). Pharmacists were (unsurprisingly) more positive in their estimation of pharmacist-success rates.68

While pharmacists cannot diagnose or perform a physical examination, checks and balances are in place to attenuate concern over this reality. For example, any self-diagnosis forwarded by any patient will not be taken at its word. A formal assessment is made before any action is taken. If improvement is not seen via pharmacist-directed care, physicians take over the care of these patients quite quickly, as per guidelines.

Irrespective of pharmacist involvement, physicians may not be fully aware of the vast amount of self-care that takes place for such conditions. While physicians highlighted the number of minor-ailment cases they see in a day, a significant percentage of individuals never seek medical care. Pharmacists represent a significant opportunity to bridge this gap. Pharmacists can help shrink treatment gaps of conditions that are currently undertreated, like allergic rhinitis and headaches, by helping patients that would not otherwise seek medical care.

Information obtained in the surveys on pharmacist referral rates and ailments of most concern may be the strongest argument to put forth in defense of the program. Physicians may not be aware that pharmacists approach minor ailments with concern and caution, just as they do. Their areas of most concern were almost an exact reflection of pharmacist-held concern.

Discussion

Minor ailments are a very common part of daily life. Canadian adults experienced an estimated 82 million headaches, 85 million colds/flu, and 46 million episodes of indigestion in one recent year.69 Most people around the world do not seek formal care for them, but those that do can impact significantly on a health care system.70–76

The situation is similar in Canada, where medical care for such ailments is costly. OTC industry executives claim that one in seven Canadians with minor ailments visits a physician.77 They go on to state that if just 16% of Canadians who relied on a physician for their mild symptoms practiced self-care instead, an additional 500,000 Canadians could have access to a family doctor. Relative to the resources consumed by minor ailments, 13% of all physician visits in Ontario (around 1989) were for colds/flu, representing 12.5% of government payments to physicians.78

Minor ailments account for approximately 10%–20% of physician workload in various locales.25,79,80 Approximately two-thirds of American physicians felt between 5% and 25% of office visits were for minor ailments that could be self-managed by the patient.80 In Saskatchewan, physicians gave similar estimates for patient load, with almost two-thirds claiming 10%–30% of appointments are primarily for minor situations.

Pharmacists, who already have a long history of minor-ailment management, appear to be a reasonable alternative for their care, yet in Saskatchewan there was not strong medical support for patients with minor ailments seeing a pharmacist first. Many physicians question whether pharmacists can differentiate something serious from something minor, given that a thorough physical examination will not be performed.

Safeguards are in place to attenuate that concern. It is likely pharmacists are aware of the risks inherent in managing minor ailments, and appear to be a cautious group. For instance, when recently asked whether three agents (simvastatin, omeprazole, fluticasone) with OTC status elsewhere in the world should be deregulated in Canada, many chose “the condition and/or the drug is too complex to manage without physician care” as reasons not to do so.81 Further, prescribing protocols in Saskatchewan (with some input from physicians) are in place for each condition. According to those guidelines, pharmacists are allowed to provide care for only mild or simple cases.

Of significant importance is that Canadians can already select OTC products for all the conditions on any given province’s list, a situation requiring no professional intervention of any sort. Pharmacists represent an orderly escalation in the care a patient can receive. If at some point a pharmacist is asked for assistance in a Saskatchewan pharmacy, guidelines require them to ask about current symptoms, whether they appear to be consistent with (for example) hemorrhoids or something more serious, and whether a physician has previously diagnosed the case.82 While it is true that no physical examination is done for any case of suspected hemorrhoids, if symptoms are present for more than 7 days despite treatment, referral to a physician is required.

With the limited amount of evaluation done so far, the public seems to welcome this option, and appears to be seeking pharmacist help judiciously. Conversely, physicians continue to be concerned with pharmacists diagnosing and the ethics of product selection connected to prescribing.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Physicians in Canada, 2014: Summary Report. Ottawa: CIHI; 2015. | ||

Family Health Online. Ask the doctor: “How much does my doctor’s visit cost?” – the value of health care. Available from: http://www.familyhealthonline.ca/fho/familymedicine/FM_CostOfDoctorVisit_FHb13.asp. Accessed June 27, 2016. | ||

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Spending. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/spending-and-health-workforce/spending. Accessed April 13, 2016. | ||

Canadian Medical Association. Basic physician facts. 2016. Available from: https://www.cma.ca/En/Pages/basic-physician-facts.aspx. Accessed June 27, 2016. | ||

Statistic Canada. Access to a regular medical doctor, 2013. Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-625-x/2014001/article/14013-eng.htm. Accessed June 27, 2016. | ||

Mehrotra A, Liu HS, Adams J, et al. The costs and quality of care for three common illnesses at retail clinics as compared to other medical settings. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:321–328. | ||

Macdonald A, Stewart M. Healthy growth: estimating the economic footprint of the fast growing consumer health products industry. 2015. Available from: http://www.chpcanada.ca/sites/default/files/healthy_growth_final_report.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2016. | ||

Canadian Pharmacists Association. Pharmacists in Canada. Available from: https://www.pharmacists.ca/pharmacy-in-canada/pharmacists-in-canada. Accessed June 27, 2016. | ||

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Pharmacists in Canada, 2009. 2009. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/en/info_pc_18nov10_pdf_en.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2016. | ||

Taylor J, Chorney S, Fleck I, et al. Assisting consumers with their OTC choices: response varied when pharmacy students offered help and information. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2006;139:38–45. | ||

Loh EA, Waruszynski MA, Poston J. Cost savings associated with community pharmacist interventions in Canada. Can Pharm J (Ott). 1996;129:43–55. | ||

Canadian Pharmacists Association. Summary: Pharmacist prescribing authority across Canada. 2009. Available from: http://www.cshp.ca/advocacy/CSHPspeaks/summary.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2016. | ||

Rent S. Scope of practice: Nfld pharmacists now allowed to assess, prescribe for minor ailments. Available from: www.canadianhealthcarenetwork.ca/pharmacists/news/professional. Accessed September 22, 2015. | ||

Morris CJ, Cantrill JA, Weiss MC. Minor ailment consultations: a mismatch of perceptions between patients and GPs. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2003;4:365–370. | ||

Yadav S. Pharmacists rather than GPs should be first contact for minor ailments, report says. BMJ. 2008;337:a775. | ||

Whittington Z, Cantrill J, Hassell K, Bates F, Noyce P. Community pharmacy management of minor conditions: the “Care at the chemist” scheme. Pharm J. 2001;266:425–428. | ||

Weinbren E. Monitor adds weight to case for national minor ailments scheme. 2013. Available from: http://www.chemistanddruggist.co.uk/news/monitor-adds-weight-case-national-minor-ailments-scheme. Accessed June 27, 2016. | ||

Gregory J. Wales launches Choose Pharmacy service for common ailments. 2013. Available from: http://www.chemistanddruggist.co.uk/news/wales-launches-choose-pharmacy-service-common-ailments. Accessed June 27, 2013. | ||

Watson MC, Ferguson J, Barton GR, et al. A cohort study of influences, health outcomes and costs of patients’ health-seeking behaviour for minor ailments from primary and emergency care settings. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006261. | ||

Welsh Government Social Research. Evaluation of the Choose Pharmacy Common Ailments Service: Final Report. Cardiff: Welsh Government; 2015. | ||

Kelly DV, Young S, Phillips L, Clark D. Patient attitudes regarding the role of the pharmacist and interest in expanded pharmacist services. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2014;147:239–247. | ||

McMillan SS, Kelly F, Sav A, King MA, Whitty JA, Wheeler AJ. Australian community pharmacy services: a survey of what people with chronic conditions and their carers use versus what they consider important. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e006587. | ||

[No authors listed]. Ontario advisory body recommends that pharmacists be granted authority to prescribe for minor ailments. Can Pharm J.2009;142(1):8. | ||

Gustafsson S, Vikman I, Axelsson K, Sävenstedt S. Self-care for minor illness. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2015;16:71–78. | ||

Banks I. Self care of minor ailments: a survey of consumer and healthcare professional beliefs and behaviour. Self Care. 2010;1:1–13. | ||

Elliott AM, McAteer A, Hannaford PC. Revisiting the symptom iceberg in today’s primary care: results from a UK population survey. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:16. | ||

Urquhart G, Sinclair HK, Hannaford PC. The use of non-prescription medicines by general practitioner attendees. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13:773–779. | ||

Hamoen M, Broekhuizen BD, Little P, et al. Medication use in European primary care patients with lower respiratory tract infection: an observational study. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64:e81–e91. | ||

Boardman H, Lewis M, Trinder P, Rajaratnam G, Croft P. Use of community pharmacies: a population-based survey. J Public Health (Oxf). 2005;27:254–262. | ||

Nonprescription Drug Manufacturers Association of Canada. Treatment choices for common ailments. Available from: www.ndmac.ca. Accessed April 26, 2000. | ||

Roper Starch. Self-Care in the New Millennium: American Attitudes Toward Maintaining Personal Health and Treatment. Washington: Consumer Healthcare Products Association; 2001. | ||

Decima Research. Attitudes, Perceptions and Behaviour Relating to Ethical Medicines: A Research Report to the Department of National Health and Welfare. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada; 1990. | ||

Proprietary Association of Great Britain. A summary profile of the OTC consumer. 2005. Available from: http://www.pagb.co.uk/publications/pdfs/Summaryprofile.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2016. | ||

UK Department of Health. Public Attitudes to Self Care Baseline Survey. London: DH; 2005. | ||

Statistics Canada. Health Services Access Survey (HSAS): detailed information for 2001. 2007. Available from: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=5002&lang=en&db=imdb&adm=8&dis=2. Accessed June 28, 2016. | ||

Epposi. The Epposi Barometer: Consumer Perceptions of Self Care in Europe. Brussels: Epposi; 2013. | ||

The Treatment of Minor Ailments in Canada: Final Report. Consumer Health Products Canada, Redfern Research, July 2011. | ||

Bojke C, Gravelle H, Hassell K, Whittington Z. Increasing patient choice in primary care: the management of minor ailments. Health Econ. 2004;13:73–86. | ||

Wood V. OTC knowledge from spectrum of sources. Pharm Post. 2002:67. | ||

Porteous T, Ryan M, Bond CM, Hannaford P. Preferences for self-care or professional advice for minor illness: a discrete choice experiment. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56:911–917. | ||

Decima Research. Public Opinion Survey on Key Issues Pertaining to Post-market Surveillance of Marketed Health Products in Canada: Final Report. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2003. | ||

Hassell K, Noyce PR, Rogers A, Harris J, Wilkinson J. A pathway to the GP: the pharmaceutical ‘consultation’ as a first port of call in primary health care. Fam Pract. 1997;14:498–502. | ||

Tio J, LaCaze A, Cottrell WN. Ascertaining consumer perspectives of medication information sources using a modified repertory grid technique. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29:73–80. | ||

Hodgson C, Wong I. What do mothers of young children think of community pharmacists? A descriptive survey. J Fam Health Care. 2004;14:73–79. | ||

Vingilis E, Brown U, Hennen B. Common colds: reported patterns of self-care and health care use. Can Fam Physician. 1999;45:2644–2652. | ||

Garofalo L, Di Giuseppe G, Angelillo IF. Self-medication practices among parents in Italy. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:580650. | ||

Farrar JR. Are you comfortable with over-the-counter intranasal steroids for children? A call to action. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:271–274. | ||

Mullol J. Positioning of antihistamines in the Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines. Clin Exp Allergy Rev. 2012;12:17–26. | ||

Brusa P, Allais G, Rolando S, et al. Migraine attacks in the pharmacy: a gender subanalysis on treatment preferences. Neurol Sci. 2015;36 Suppl 1:93–95. | ||

Azari AA, Barney NP. Conjunctivitis: a systematic review of diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2013;310:1721–1729. | ||

Wolffsohn J, Naroo SA, Gupta N, Emberlin J. Prevalence and impact of ocular allergy in the population attending UK optometric practice. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2011;34:133–138. | ||

Baldwin HE, Kawata AK, Daniels SR, Wilcox TK, Burk CT, Tanghettin EA. Impact of female acne on patterns of health care resource utilization. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:140–148. | ||

Molnar C, Fusco J. Overactive bladder: OTC oxybutynin transdermal patch for women. Consult Pharm. 2014;29:703–707. | ||

Campbell MK, Silver RW, Hoch JS, et al. Re-utilization outcomes and costs of minor acute illness treated at family physician offices, walk-in clinics, and emergency departments. Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:82–83. | ||

Paudyal V, Watson MC, Sach T, et al. Are pharmacy-based minor ailment schemes a substitute for other service providers? A systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e472–e481. | ||

Research Power. Evaluation of the Provision of Minor Ailment Services in the Pharmacy Setting Pilot Study. Dartmouth (NS): Pharmacy Association of Nova Scotia; 2013. | ||

Nova Scotia College of Pharmacists. Standards of Practice: Prescribing of Drugs by Pharmacists. Halifax (NS): Nova Scotia College of Pharmacists; 2011. | ||

Rent S. Nova Scotia to fund assessments of three minor ailments. Available from: www.canadianhealthcarenetwork.ca/pharmacists/news/professional. Accessed April 4, 2015. | ||

Pojskic N, Mackeigan L, Boon H, Austin Z. Initial perceptions of key stakeholders in Ontario regarding independent prescriptive authority for pharmacists. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2014;10:341–354. | ||

McMaster Health Forum. Citizen Brief: Exploring Models for Pharmacist Prescribing in Ontario. Hamilton (ON): McMaster University; 2015. | ||

Ontario Pharmacists Association. Value of expanded authority release. 2013. Available from: https://www.opatoday.com/professional/news/value-of-expanded-authority-release. Accessed June 28, 2016. | ||

Ontario Pharmacists Association. Common ailments survey: the results from members are encouraging. 2014. Available from: https://www.opatoday.com/common_ailments_results. Accessed June 28, 2016. | ||

Pharmacy Association of Saskatchewan. Members’ update. 2015. Available from: https://www.skpharmacists.ca/uploads/media/57598f5d98894/PAS%20Members’%20Update%202015%20(FINAL).pdf?v1.Accessed June 28, 2016. | ||

Taylor J. Minor ailment prescribing: part II – physician feedback. Self Care. 2016;7:22–40. | ||

Bootsman N, Taylor J. The requirement for a patient’s self-diagnosis within the minor ailments prescribing process in a Canadian province: a commentary. Self Care. 2014;5:2–10. | ||

University of Saskatchewan. Guidelines for minor ailment prescribing. 2013. Available from: http://www.medsask.usask.ca/about-us/disclaimer-and-privacy-statement/index.php. Accessed June 28, 2016. | ||

Mansell K, Bootsman N, Kuntz A, Taylor J. Evaluating pharmacist prescribing for minor ailments. Int J Pharm Pract. 2015;23:95–101. | ||

Taylor J, Mansell K. Minor ailment prescribing: part I – pharmacist feedback. Self Care. 2016;7:10–21. | ||

Willemsen KR, Harrington G. From patient to resource: the role of self-care in patient-centered care of minor ailments. Self Care. 2012;3:43–55. | ||

McAteer A, Elliot AM, Hannaford PC. Ascertaining the size of the symptom iceberg in a UK-wide community-based survey. Br J Gen Pract.2011;61:e1–e11. | ||

UK Department of Health. Self care – a real choice: self-care support – a practical option. 2013. Available from: http://personcentredcare.health.org.uk/resources/self-care-%E2%80%93-real-choice-self-care-support-%E2%80%93-practical-option. Accessed June 28, 2016. | ||

Pillay N, Tisman A, Kent T, Gregson J. The economic burden of minor ailments on the National Health Service in the UK. Self Care. 2010;1:105–16. | ||

Sauro A, Barone F, Blasio G, Russo L, Santillo L. Do influenza and acute respiratory infective diseases weigh heavily on general practitioners’ daily practice? Eur J Gen Pract. 2006;12:34–36. | ||

Fielding S, Porteous T, Ferguson J, et al. Estimating the burden of minor ailment consultations in general practices and emergency departments through retrospective review of routine data in North East Scotland. Fam Pract. 2015;32:165–172. | ||

Amiel C, Williams B, Ramzan F, et al. Reasons for attending an urban urgent care centre with minor illness: a questionnaire study. Emerg Med J. 2014;31:e71–e75. | ||

Gustafsson S, Vikman I, Axelsson K, Sävenstedt S. Self-care for minor illness. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2015;16:71–78. | ||

Côté D. CHP Canada featured in global news story on self-care. 2015. Available from: http://www.chpcanada.ca/en/blog/chp-canada-featured-global-news-story-self-care. Accessed June 28, 2016. | ||

Weinkauf DJ, Rowland GC. Patient conditions at the primary care level: a commentary on resource allocation. Ont Med Rev. 1992;59:11–15,61. | ||

Welle-Nilsen LK, Morken T, Hunskaar S, Granas AG. Minor ailments in out-of-hours primary care: an observational study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2011;29:39–44. | ||

Consumer Healthcare Products Association. Your health at hand: perceptions of over-the-counter medicine in the U.S. 2010. Available from: http://www.yourhealthathand.org/images/uploads/CHPA_YHH_Survey_062011.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2016. | ||

Lalonde L, Tsuyuki RT, Landry E, Taylor J. Results of a national survey on OTC medicines, part 2: do pharmacists support switching prescription agents to over-the-counter status? Can Pharm J (Ott). 2012;145:73–76. | ||

University of Saskatchewan. Pharmacist assessment – hemorrhoids. Available from http://medsask.usask.ca/documents/pdfs/hemorrhoids_assessment.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2016. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.