Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 9

Perspectives of patients on factors relating to adherence to post-acute coronary syndrome medical regimens

Authors Lambert-Kerzner A, Havranek E, Plomondon M, Fagan K, McCreight M, Fehling K, Williams D, Hamilton A, Albright K, Blatchford P, Mihalko-Corbitt R, Bryson C, Bosworth H , Kirshner M, Del Giacco E, Ho PM

Received 13 March 2015

Accepted for publication 7 May 2015

Published 24 July 2015 Volume 2015:9 Pages 1053—1059

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S84546

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Anne Lambert-Kerzner,1,2 Edward P Havranek,2,3 Mary E Plomondon,1,2 Katherine M Fagan,1 Marina S McCreight,1 Kelty B Fehling,1 David J Williams,2 Alison B Hamilton,4 Karen Albright,2 Patrick J Blatchford,2 Renee Mihalko-Corbitt,5 Chris L Bryson,6 Hayden B Bosworth,7 Miriam A Kirshner,7 Eric J Del Giacco,5 P Michael Ho1,2

1Department of Cardiology, Veterans Health Administration (VA) Eastern Colorado Health Care System, Denver, CO, 2School of Public Health or School of Medicine, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, 3Cardiology, Denver Health Medical Center, Denver, CO, 4Health Services Research, Veterans Health Administration (VA) Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, CA, 5Internal Medicine, John L. McClellan Memorial Veterans Hospital, Little Rock, AR, 6Health Services Research, Veterans Health Administration (VA) Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, WA, 7Health Services Research, Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA

Purpose: Poor adherence to cardioprotective medications after acute coronary syndrome (ACS) hospitalization is associated with increased risk of rehospitalization and mortality. Clinical trials of multifaceted interventions have improved medication adherence with varying results. Patients’ perspectives on interventions could help researchers interpret inconsistent outcomes. Identifying factors that patients believe would improve adherence might inform the design of future interventions and make them more parsimonious and sustainable. The objective of this study was to obtain patients’ perspectives on adherence to medical regimens after experiencing an ACS event and their participation in a medication adherence randomized control trial following their hospitalization.

Patients and methods: Sixty-four in-depth interviews were conducted with ACS patients who participated in an efficacious, multifaceted, medication adherence randomized control trial. Interview transcripts were analyzed using the constant comparative approach.

Results: Participants described their post-ACS event experiences and how they affected their adherence behaviors. Patients reported that adherence decisions were facilitated by mutually respectful and collaborative provider–patient treatment planning. Frequent interactions with providers and medication refill reminder calls supported improved adherence. Additional facilitators included having social support, adherence routines, and positive attitudes toward an ACS event. The majority of patients expressed that being active participants in health care decision-making contributed to their health.

Conclusion: Our findings demonstrate that respectful collaborative communication can contribute to medication adherence after ACS hospitalization. These results suggest a potential role for training health-care providers, including pharmacists, social workers, registered nurses, etc, to elicit and acknowledge the patients’ views regarding medication treatment in order to improve adherence. Future research is needed with providers to understand how they elicit and acknowledge patients’ views, particularly in the face of nonadherence, and with patients to understand how to empower them to share their opinions with their providers.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, compliance, qualitative analysis, medications

Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is the leading cause of death and disability in the United States.1 Nonadherence to proven cardiovascular medications is common following hospitalization for an ACS event and may result in serious complications, including recurrent hospitalization and death.2–6 Multifaceted interventions targeting medication adherence and health behaviors have demonstrated varying results.7,8 Understanding patients’ perspectives on their experiences following an ACS event and their opinions of the effectiveness of such interventions may support adherence behaviors.9

The high prevalence of medication nonadherence following an ACS event is not surprising considering that evidence-based treatment plans are often complex and lifelong.2–6 Adherence declines over time following hospital discharge, with one-third of patients stopping at least one medication within 1 month3–6 and 40% of patients discontinuing statins within 1 year.2,3,10 Mitigating the consequences of poor adherence to cardiac medications remains a major public health challenge.11

Therefore, understanding and identifying factors that support positive adherence behavior in a predominately older male population, who are at a higher risk for an ACS event,1 is needed to shed light on this pervasive issue. While the literature identifies barriers to adherence, including health systems, condition, patient, therapy, and socioeconomic-related factors,11 no prior studies have identified patients’ perspectives on supportive adherence factors after an ACS event and their participation in a medication adherence randomized control trial (RCT). Recommendations of the International Expert Forum on Patient Adherence9,12 support exploring patients’ beliefs about adherence. Moreover, intervention experts such as the Medical Research Council13–15 support exploring participants’ perspectives on the effectiveness of the interventions.

The goal of this qualitative study was to obtain patients’ perspectives on supportive adherence factors to medical regimens after experiencing an ACS event and their participation in an RCT that facilitated medication adherence following their hospitalization.

Material and methods

Study design and sample

Participants in this qualitative study were enrolled in the “Multi-Faceted Intervention to Improve Cardiac Medication Adherence and Secondary Prevention Measures – The Medication Study.”2,3 The details of the study have been published previously.2,3 The RCT enrolled 253 patients and compared medication adherence at 1 year between usual care and a multimodal intervention. This intervention comprised: 1) medication reconciliation and patient support provided by study pharmacists; 2) patient education; 3) automated medication refill reminder calls on specific days prior to the refill day and monthly educational calls; and 4) collaboration between pharmacists and clinicians when needed. The RCT was conducted at four Veterans Health Administration medical centers (Denver, Little Rock, Durham, and Seattle) and significantly improved the proportion of patients adherent to medications (patient days covered >0.80) compared to usual care (89.3% vs 73.9%, P=0.003).2,3

Data collection

Owing to budget constraints, we utilized a convenience sample at the Denver site by approaching all participants who completed the final visit (n=51). All those approached agreed to participate in the interviews. Then to assess new or different data from the other three sites, the project managers at their respective sites randomly chose participants and asked if they would participate in the interviews. In Seattle, seven patients were approached and all of them agreed; in Little Rock, five were approached and three of them agreed; and in Durham, three of them were approached and all of them agreed. This sample was interviewed in person or through telephone by a member of the trained qualitative team (ALK, MSM, KMF, and MK). Qualitative interview data were collected from August 2011 to May 2013. The purpose of the interview was to gather 1) in-depth understanding about the experience after an ACS event; 2) the effect of relationships with providers on their adherence behaviors; and 3) opinions about the RCT study. The 45–60-minute interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Baseline demographics, including age, sex, race, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, and coronary artery disease, were obtained to characterize the study population. This qualitative study was approved as part of the RCT by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.2,3

Data analysis

An iterative analysis, drawing primarily on constant comparative methodology, was used. This involved moving back and forth between interview transcripts to support the evolution of the process by identifying emerging themes and defining the relationships between them.16–19 The validity and the accuracy/reliability of the early codes were established by each member of the experienced qualitative team (ALK, MSM, KMF, and KBF) analyzing the initial four transcripts, coming to consensus, thus defining the initial codebook. Emergent codes were added throughout the analysis. The remaining interviews were divided among the team and coded using ATLAS.ti (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH). The consistency of coding/interpretation was checked at biweekly meetings where discrepancies were addressed through consensus. Triangulation of the qualitative findings, observations, and the RCT quantitative findings were integrated and documented with an audit trail.16–19 Illustrative quotes were selected by consensus with all members of the analytic team to ensure representativeness across roles and participating sites.

Participants

Sixty-four patients who completed the final study visit were interviewed. The majority of the patients interviewed were from Denver (n=51), Seattle (n=7), Little Rock (n=3), and Durham (n=3). Of the 64 patients, 33 (52%) were from the intervention group and 31 (48%) from the usual care.

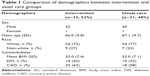

Baseline demographics and comorbidities were comparable between the two groups (Table 1). Most participants were male (97%) and white (75%). The majority of participants were 50 years and older (95%) with a mean age of 66.5 years, similar to the Veterans Health Administration population. We compared adherence between the interviewed subgroups (intervention and control patients) and the corresponding patients in the entire RCT intervention and control groups. For example, the adherence of the interviewed intervention patients was compared to the total RCT intervention patients. Through this comparison, we found that the qualitative subgroups (intervention and control) were more adherent than the corresponding groups in the entire RCT (97% vs 89% for the intervention and 80% vs 73% for the control).

| Table 1 Comparison of demographics between intervention and usual care groups |

Results

Understanding patients’ experiences after an ACS event shed important insight into reasons behind their adherence behaviors. Although patients shared the same diagnosis, their experiences of the ACS event, its consequences, and the ways in which it impacted their health behavior decisions varied. Patients identified positive and accepting attitudes toward their cardiac issues, supportive social relationships, and specific adherence tools as being important in improving their lifestyles. The most consistent insight shared by patients was that bidirectional communication and specifically, mutually respectful collaboration about their treatment plan between themselves, their care providers, and families led to better medication adherence.

Experiencing an ACS event

Most patients experiencing an ACS event considered it to be profound and life-changing. Many stated their life changed due to mental and physical limitations, which affected multiple aspects of their lives, including relationships with significant others, their identity, roles in their lives, and activities they enjoyed doing with others.

Everything changed … I got back to religion, I got in a better relationship with my wife and my kids ‘cause I didn’t know how long I was going to be around!

It means that I can’t do what I used to be able to do and frankly I get, oh, not depressed but a little sad […] I can’t even mow my own lawn,… And, it concerns me because I used to be a really strong guy.

A few patients lost their sense of identity and self-esteem from no longer being able to complete everyday tasks and participate in leisure activities.

Very depressing, ‘cause it stopped everything I did. I can’t do what I did before, like fly airplanes and so on. I was a pilot for a living, so I lost that, it was my hobby and everything so it changed my whole life.

Many patients admitted to being fearful, concerned, devastated, sad, or depressed in the year after experiencing their ACS event. For some, these negative emotional trajectories monopolized their lives.

Very strenuous, you know, physically and mentally. Having this heart condition you don’t know when you’re … gonna have the next one, you know, the next heart attack so.

Effect of experiencing an ACS event on adherence behaviors

Ultimately, the impact of the ACS event itself was a double-edged sword, either motivating or hindering patients’ abilities to effectively change their health behaviors. Most patients were motivated to improve their health behaviors.

They […] put stents in and it […] woke me up and now I work out every day

and

It was devastating.[…] it made me really […] look at my life, change it.

Approximately half of the patients said having positive and accepting attitudes toward their cardiac issues allowed them to forge ahead and become proactive in improving their lifestyles.

It means that I need to take better care of myself. Give up the old habits of smoking,[…] and to take my prescribed medication on time. Try to eat a balanced diet and try to keep my health better and my weight down, cholesterol down. There’s just so many things we have to live for,[…] grandchildren,[…] And my wife,[…] so […] got to watch my health.

For others, these emotions paralyzed their ability to move forward. They were fearful of having another heart attack, and a few patients described a realization of their mortality, resulting in their refusal to adhere to prescribed medications, activities, and/or stopped previous exercise routines.

Before, it was basically five days … a week … I would be in the gym doing some sort of activity [and after]. Little more than the desire to not work out due to the heart attack. The fear that I’m gonna do something wrong and wind up exacerbating the condition.

Effect of relationships with providers on adherence behaviors

Positive health-care relationships

Two-third of the patients identified the importance of bidirectional communication in their relationship with their providers. They expressed the importance of being heard, and shared that they were comfortable disagreeing with the providers’ recommendations and wanted providers to be open to hearing patients’ perspectives, thus defining a mutually respectful collaboration with their providers. Moreover, these patients felt they were active participants in the development of their treatment plan, which they believed was essential for high quality care.

[…] how [would he] know what was best for me if I can’t tell him how I feel about it?

These patients emphasized the importance of being able to ask clarifying questions about their treatment plans without fear of a condescending response. Patients shared that they were equally responsible in this relationship and it was their duty to help providers remember specific details about themselves. Participants reported that bidirectional communication with their providers, specifically collaboration in their development of a treatment plan, supported constructive adherence decisions.

Yep, with the primary care, we were talking about something […] about medications actually and I believe he said something to the effect of taking the medications he prescribes and he wasn’t being combative about it, but I made sure that the context of the instruction was that I agreed with taking the medication. You know in the long run, people can prescribe medication but it is up to me to decide if I will take it or not, and I take it by the way.

Two-third of the intervention arm had positive experiences, specifically with the study pharmacists, who were perceived to be supportive providers and caring individuals.

It [working with the pharmacist] makes me feel important, like I am a person, not just a number. [and]. Makes me want to do it.

Especially on the heart medicines. Uh … that … it made me think that it musta’ been more important than I thought it was … to have these people contact me on a regular basis to make sure I was takin’ it. So I think it did show me a little bit more of the importance of … of taking them.

Negative health-care relationships

However, some patients shared negative experiences with their providers and described a lack of basic communication. Seventeen percent of the patients said they were not comfortable sharing divergent opinions or misunderstandings of medications with their providers. Nine percent specifically said they would not tell their provider if they disagreed with the prescribed treatment.

But I just don’t want to argue with him to tell him, he’s not in my body. And I know what I feel and he can’t tell me what I feel.

Adherence was negatively affected when patients were concerned about the side effects of medications but not comfortable discussing these with their provider.

Well, they keep telling me that everything is fine, [if] everything is fine, then I don’t see the reason why I can’t get off of them [medications].

When a patient was asked his perspective when talking about medicines with his doctor, he replied:

I don’t understand them sometimes. [Patient (P)]

Do you ask questions? [Interviewer (I)]

No … I don’t know I just don’t. [P]

Can you tell us why you did not take them (the medicines)? [I]

Because I was afraid of the medicine I was taking. I didn’t know how I would react on it. [P]

Okay, could you tell me a little bit about why you do not think you could disagree with the doctor? [I]

I’m just not that type. [P]

Finally, a few patients shared that their providers were not open to hearing patients’ opinions. One woman shared that she felt comfortable telling a provider she did not agree with him, even if the provider did not respond well.

Oh yeah, I do … but they don’t. Well you know it’s my body, and I have to live in it, they don’t.

And:

And he’s acting like I got no business being there … Nobody knows my body like I know my body! And he finally agreed to do another arteriogram and that’s when they found out that one graft was 100% blocked!

Others shared their providers were condescending.

The doctors don’t think that we’re capable of understanding sometimes.

Supplementary adherence factors

Most of the participants realized they needed help to adhere to their medical regimens and identified supportive factors, including social support from family members, friends, and neighbors; pill boxes; storing medications in an easily seen place; taking them the same time every day; using the alarm on phones/watches; and writing in a notebook or on the medication lids.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to elicit patients’ perspectives on their experiences after an ACS hospitalization and their participation in an adherence intervention. More specifically, we intended to elicit patients’ perspectives on their adherence behaviors to recommended medical regimens, including medications and health behaviors. This predominately male, veteran population exhibited above average adherence to their cardiovascular medications, allowing us to identify factors relating to high adherence in a high-risk population. Veterans expressed the significance of feeling cared for by their providers, including the study pharmacists, which empowered them to be active in their health care. We found that a focus on a mutually respectful collaboration supported adherence decisions.

The importance of patient–provider communication is well documented in the health communication literature, especially among patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).20–29 Mulder et al28 and Apollo et al29 highlight that HIV patients desire to go beyond just sharing in the decision-making process. They want to be collaborative in the process of medication decision-making. Our study contributes to the literature by identifying similar findings within patients with cardiovascular disease, specifically ACS. In fact, adherence experts have emphasized that understanding adherence behaviors in relation to each disease condition was an important aspect of adherence to the prescribed medications.22–25 In contrast to prior studies that have focused on nonadherence behaviors, our unique study focuses on facilitators of adherence. Understanding this unique population of predominately older males, who remain at higher risk for an ACS event,1 provides a contemporary perspective into adherence behaviors. The distinctiveness of the male adherence behavior indicates that worse health outcomes are due in part to men’s health-related beliefs and behaviors, which include denial of weakness or vulnerability, control, and the appearance of being strong with the dismissal of need for help.30,31 Men may believe it is unacceptable to express emotional or physical pain with other men.30 These male-specific factors may explain the post-ACS reactions of participants that resulted in their inability to adhere to prescribed medications, activities, and/or stopping previous exercise routines and discomfort sharing their feelings with their providers.

Therapeutic Alliance,32–35 a theory that describes a patient’s and a physician’s working alliance in relation to the patient’s health and health care decisions, further supports our findings of why patients were paralyzed in their ability to move forward and the importance of collaborative care. ACS events can evoke complex psychological reactions, as described by the veterans. Patients vary in their capacity to use this information about their health productively to develop and maintain new health behaviors. When patients struggle to adhere to medications, they may have difficulty communicating this information to their physician.32–35 Therefore, the importance of patients’ and physicians’ shared sense of purpose and effort around treatment goals is paramount to the quality of the patients’ outcomes. Our findings demonstrated that when patients were more engaged and participated in the development of the treatment plan, they were more likely to implement the treatment plan. Consequently, patients were empowered, gaining greater control over decisions and actions that affected their health.36

Yet, despite the importance of increased patient involvement and empowerment around health-care decisions, such as in Patient-Centered Care and Shared Decision Making37,38 paradigms, not all practitioners are successful implementing these shared and collaborative decision-making concepts.39,40 Mulder et al found that when patients failed to adhere, providers reverted to a more paternalistic approach, using risk communication about consequences of nonadherence.28 Moreover, when providers fail to utilize a collaborative process with patients, they are unaware of the actual adherence behavior of the patient. When the provider is aware the patient will not follow through with the prescribed treatment plan, the collaborative process allows the provider the opportunity to offer alternative options, which may not be optimal but ultimately may be better than no care.

Potential limitations

Our results are based on patients enrolled in an RCT and may be subject to attribution bias. The study comprises mainly male participants. However, since men are at a higher risk for an ACS event, understanding the male perspective might be considered a strength of the study. The study results were based on interview data and did not include any direct observations of the patients using the intervention components.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings, from the patients’ perspectives, confirm that the collaborative patient–provider relationship can enhance and contribute to medication adherence in an already adherent population. As we have stated, the overall adherence rate of these patients in both intervention and control groups was above average, which is not typically representative of this population.

These results suggest a potential role for training health care providers to elicit and acknowledge patients’ views and empower patients to speak up regarding medication treatment in order to improve adherence. Therefore, further research is needed with providers in order to understand how they elicit and acknowledge patients’ views regarding treatment over time, particularly in the face of nonadherence.

Disclosure

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2014 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation. 2014;128:e28–e292. | ||

Ho PM, Lambert-Kerzner A, Carey EP, et al. Multifaceted intervention to improve medication adherence and secondary prevention measures after acute coronary syndrome hospital discharge. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;174(2):186–193. | ||

Lambert-Kerzner A, Del Giacco EJ, Fahdi IE, et al. On behalf of the Multifaceted Intervention to Improve Cardiac Medication Adherence and Secondary Prevention Measures Medication Study Investigators@@Patient-centered adherence intervention after acute coronary syndrome hospitalization. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:571–576. | ||

Jackevicius CA, Li P, Tu JV. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of primary nonadherence after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117:1028–1036. | ||

Ho PM, Spertus JA, Masoudi FA, et al. Impact of medication therapy discontinuation on mortality after myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1842–1847. | ||

Rasmussen JN, Chong A, Alter DA. Relationship between adherence to evidence-based pharmacotherapy and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2007;297:177–186. | ||

Bosworth H, Olsen M, Grubber J, et al. Two self-management interventions to improve hypertension control. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:687–695. | ||

Green B, Cook A, Ralston J, et al. Effectiveness of home blood pressure monitoring, web communication, and pharmacist care on hypertension control: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:2896–2898. | ||

Van Dulmen S, Sluijs E, Van Dijk L, de Ridder D, Heerdink R, Bensing J. Furthering patient adherence: a position paper of the international expert forum on patient adherence based on an internet forum discussion. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:47. | ||

Maddox TM, Plomondon ME, Ho PM, et al. Factors associated with statin adherence after acute coronary syndrome. Abstract presented at: American Heart Association, 8th Scientific Forum on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research in Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke; May 9–11; 2007; Washington, DC. | ||

Grangera BB, Bosworth HB. Medication adherence: emerging use of technology. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2011;26:279–287. | ||

Van Dulmen S, Sluijs E, Van Dijk L, De Ridder D, Heerdink R, Bensing J. Patient adherence to medical treatment: a review of reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:55. | ||

Craig P, Dieppe P, MacItyre S, Mitchie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical research council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:979–983. | ||

Campbell N, Murray E, Darbyshire J, et al. Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. BMJ. 2007;334:455–459. | ||

Pawson R. Evidence-Based Policy: A Realist Perspective. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2006. | ||

Creswell J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd; 2007. | ||

Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2006. | ||

Patton M. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd; 2002. | ||

Bradley E, Curry L, Devens K. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1758–1772. | ||

Garavalia L, Ho PM, Garavalia B, et al. Clinician-patient discord: exploring differences in perspectives for discontinuing clopidogrel. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;10:50–55. | ||

Garavalia L, Garavalia B, Spertus JA, Decker C. Exploring patients’ reasons for discontinuance of heart medications. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;24:371–379. | ||

Monroe AK, Rowe TL, Moore RD, Chander G. Medication adherence in HIV-positive patients with diabetes or hypertension: a focus group study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:488–495. | ||

Teferra S, Hanlon C, Beyero T, Jacobsson L, Shibre T. Perspectives on reasons for non-adherence to medication in persons with schizophrenia in Ethiopia: a qualitative study of patients, caregivers and health workers. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:168–177. | ||

Marshall IJ, Wolfe CD, McKevitt C. Lay perspectives on hypertension and drug adherence: systematic review of qualitative research. BMJ. 2012;345:e3953–e3969. | ||

Lewis LM, Askie P, Randleman S, Shelton-Dunston B. Medication adherence beliefs of community-dwelling hypertensive African Americans. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25:199–206. | ||

Lehane E, McCarthy G, Collender V, Deasy A. Medication-taking for coronary artery disease – patients’ perspectives. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;7:133–139. | ||

Bergman E, Bertero C. You can do it if you set your mind to it: a qualitative study of patients with coronary artery disease. J Adv Nurs. 2001;36:733–741. | ||

Mulder BC, van Lelyveld MA, Vervoort SC, et al. Communication between HIV patients and their providers: a qualitative preference match analysis. Health Commun. 2014;20:1–12. | ||

Apollo A, Golub SA, Wainberg ML, Indyk D. Patient-provider relationships, HIV, and adherence. Soc Work Health Care. 2006;42:209–224. | ||

Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: a theory of gender and health. Soc Sci Med. 2000; 50:1385–1401. | ||

Smith JA, Braunack-Mayer A, Wittert G. What do we know about men’s help-seeking and health service use? Med J Aust. 2006;184:81–83. | ||

Squier R. A model of empathic understanding and adherence to treatment regimens in practitioner-patient relationsips. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30:325–339. | ||

Fuertes JN, Mislowack A, Bennett J, et al. The physician–patient working alliance. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66:29–39. | ||

Kim SC, Boren D. The quality of therapeutic alliance between patient and provider predicts general satisfaction. Mil Med. 2008;173:85–90. | ||

Auchincloss EL, Samber E, American Psychoanalytic Association. Psychoanalytic Terms and Concepts. Auchincloss EL, Samber E, editors. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press; 2012:264–265. | ||

Nutbeam D. Health promotion glossary. Health Promot Int. 1998;13:349–364. | ||

Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (Or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:681–692. | ||

Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1361–1367. | ||

Rosenbaum L. When Doctors Tell Patients What They Don’t Want to Hear The New Yorker. New York (NY): Condé Nast; 2013. | ||

Sepucha KR, Fagerlin A, Couper MP, Levin CA, Singer E, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. How does feeling informed relate to being informed? The DECISIONS survey. Med Decis Making. 2010;30:77S–84S. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.