Back to Journals » Risk Management and Healthcare Policy » Volume 13

Perspectives of Migrants and Employers on the National Insurance Policy (Health Insurance Card Scheme) for Migrants: A Case Study in Ranong, Thailand

Authors Srisai P, Phaiyarom M , Suphanchaimat R

Received 16 June 2020

Accepted for publication 24 September 2020

Published 20 October 2020 Volume 2020:13 Pages 2227—2238

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S268006

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Marco Carotenuto

Patinya Srisai,1 Mathudara Phaiyarom,1 Rapeepong Suphanchaimat1,2

1International Health Policy Program (IHPP), The Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi 11000, Thailand; 2Division of Epidemiology, Department of Disease Control, The Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi 11000, Thailand

Correspondence: Patinya Srisai

International Health Policy Program (IHPP), The Ministry of Public Health, 88/20 Satharanasuk 6 Alley, Tambon Bang Khen, Mueang Nonthaburi District, Nonthaburi 11000, Thailand

Tel +66-2-590-2366

Fax +66-2-590-2385

Email [email protected]

Background and Purposes: Thailand has implemented a nationwide insurance policy for migrants, namely the Health Insurance Card Scheme (HICS), for a long time. However, numerous implementation challenges remain and migrant perspectives on the policy are rarely known. The aim of this study was to examine migrant service users’ perspectives and their consequent response towards the HICS.

Methods: A qualitative case-study approach was employed. In-depth interviews with ten local migrants and four employers were conducted in one of the most densely migrant-populated provinces in Thailand. Document review was used as a means for data triangulation. Inductive thematic analysis was exercised on interview data.

Results: The findings revealed that most migrants were not aware of the benefit, they are entitled to receive from the HICS due to unclear communication and inadequate announcements about the policy. The registration costs needed for legalising migrants’ precarious status were a major concern. Adequate support from employers was a key determining factor that encouraged migrants to participate in the registration process and purchase the insurance card. Some employers sought assistance from private intermediaries or brokers to facilitate the registration process for migrants.

Conclusion: Proper communication and promotion regarding the benefits of the HICS and local authorities taking action to expedite the registration process for migrants are recommended. The policy should also establish a mechanism to receive feedback from migrants. This will help resolve implementation challenges and lead to further improvement of the policy.

Keywords: migrants, health insurance, health policy, health service user, policy implementation, Thailand

Introduction

Migrant health has become a major global policy discourse due to a high health burden, especially infectious diseases-related mortality in a large number of migrants.1 It is believed that nearly 258 million people or 3.4% of the global population resides outside their own country of origin.2 This number is predicted to increase and exceed 405 million people in next three decades.3 It is due to the rapid growth of human mobility which has several contributing factors, such as economic opportunity, convenient transportation, political conflict, violence, and human trafficking.3

The issue of migrant health protection has been considered globally at many high-level meetings, such as the United Nations General Assembly meeting in 2006, the World Health Assembly (WHA) with Resolutions WHA 60.26, WHA 61.17, and WHA 70.15, and the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration adopted by Member States of the United Nations in 2018.4–8 In 2015, migrant health received increased global attention when the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) included migrant health as fundamental in achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) under the principle of “Leave no one behind”9 The pathway to achieve such a goal requires huge effort from all sectors including immigration control, the security sector, labour authorities, and the public health arena as well as the implementation of migration laws and citizenship regulations in each individual country.10

Thailand is a major migration hub as its location is suitable as a centre of transition and destination among countries in Southeast Asia. Due to the country’s rapid economic growth, it receives a huge number of migrants from neighbouring populations especially Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, and Vietnam (CLMV nations).11 In 2018, the cumulative volume of non-Thai people in Thailand was about 4.9 million. Among these, 3.9 million were CLMV migrant workers and dependants. Over half of them entered the country without valid travel documents, and are recognised as undocumented migrants.11 A recent report by the International Labour Organization suggested that migrants contributed about 4.3–6.6% of Thai gross domestic product in 2010.12 This situation, among other aspects, leads the Thai government to exercise lenient measures to legalize and register these undocumented migrants rather than a deportation policy. One key measure is nationality verification (NV). With NV, undocumented migrants are able to reside and work in the country lawfully.13 The NV policy is implemented alongside a measure to protect the health of migrants. The most distinct health policy for migrants is the “Health Insurance Card Scheme” (HICS), a national insurance scheme for CLMV migrants managed by the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH).14

The HICS benefit package is comprehensive, covering all types of care including health promotion and disease prevention activities. The HICS is financed by an annual premium. The HICS revenues are pooled at the central MOPH and later redistributed in a decentralized manner to the local health facilities. An insuree does not need to pay for any cost upfront, except a US$ 1 administrative fee. The card price gradually increased over a period of years from 1300 Baht (US$ 39) between 2004 and 2013 to 2200 Baht (US$ 67) in 2013. This was because in 2013 the MOPH expanded the HICS benefit to include HIV/AIDS treatment and certain high-cost treatments.15

Migrants who enter the country lawfully and work in the formal sector (like firms, factories or enterprises) need not buy the HICS as they are covered by the Social Security Scheme (SSS), which is the same social insurance for Thai formal workers. The SSS is financed by tri-partite contributions, equally shared between employer and employee (5% of the employee’s salary and 5% subsidies of employer) as well as 2.75% from the government. The SSS is managed by the Ministry of Labour (MOL). The benefit packages of the HICS are quite similar to the SSS. One of the most remarkable differences between the two schemes is that the SSS provides additional non-health benefits for its beneficiaries (such as a pension and unemployment allowance).

In mid-2014, after the military coup in Thailand, the military government launched a “One Stop Service” (OSS) policy to facilitate the registration of undocumented migrants and to expedite the NV process. The policy message at that time was quite strong that those failing to register with the OSS would be deported. At the same time, the HICS premium was reduced in order to attract more migrants to enrol in the scheme.16 From 2014, the MOPH reduced the HICS premium to 1600 Baht (US$ 48) for a migrant adult, plus 500 Baht (US$ 15) for a health check-up before being enrolled in the scheme, and 365 Baht (US$ 12) for a migrant child aged less than seven years.14,16

Despite these numerous proactive measures, evidence suggests that implementation gaps remain as a result of inadequate communication between related authorities particularly the Ministry of Interior, the Minister of Labour, and the Minister of Public Health, and unclear policy implementation guidelines. For example, whether migrant employees or Thai employers are responsible for the HICS payment, and if migrants failing to register with the OSS are still able to buy the HICS.10 Although policy implementation challenges from providers’ perspectives were mentioned in some literature, little is known about the perceptions and practices of migrant service users and their employers. Though it was previously discovered that HICS contributed to increased service utilization among migrants, the rate of service utilization was still lower than the main insurance scheme of Thai citizens (Universal Coverage Scheme).17 As the ultimate goal of Universal Health Coverage is to “leave no one behind” and to assure that everyone receives quality healthcare without incurring excessive healthcare spending, it is necessary to explore the possible challenges of using the HICS from both migrants’ and employers’ perspectives. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the migrants’ and employers’ perspectives and their responses to the HICS as part of the OSS.

It is hoped that findings from this study will not only extend the value and academic richness of public health research on migrant health in Thailand, but also help inform policy makers in other countries, especially lower- and middle-income nations, to further improve migrant health policy implementation. Moreover, this study may contribute to a better understanding of the HICS and lead to the improvement of the HICS on the ground. Policy makers and frontline implementers may use these findings to tailor health services for migrants by making the insurance scheme more responsive to the health behaviour and perspectives of migrants.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Study Site

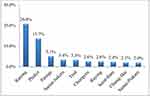

A qualitative case-study approach was employed. Ranong, a province in the southern region of Thailand, was selected as a study site. This is because it is an area with the highest ratio of insured migrants to Thai citizens (Figure 1).18 Within the province, the research team focused on two districts with the highest number of migrants namely Mueang and Kraburi districts. Mueang is the headquarter district of the province. It is geographically located next to Victoria Point, one of the major business cities of South Myanmar. Common occupations for migrants in Mueang district lie within fishing industries, construction, and the service sector. By contrast, Kraburi is more rural and most migrants are involved in the agricultural sector (rubber farming and rice planting).19

|

Figure 1 Percentage of insured migrants to Thai citizens among the top-ten provinces in Thailand. |

Sampling Strategy and Data Collection

Sampling Strategy

In order to examine the degree to which the migrant health policy is fulfilling migrant health needs, ten households with at least one member in the family with severe or chronic disease were purposively recruited. The family members’ insurance status and household characteristics were taken into consideration to assure a good mix of migrants’ background. Since some migrants were in precarious legal status, the researchers faced many challenges in identifying them. Thus, the researchers started identifying potential interviewees by discussing with local healthcare officers at the health centres and local non-government organizations (NGOs) and asked them to facilitate the research team’s entry into the field.

Additionally, the research team conducted the interviews with the employers of these migrants (n=4) in order to seek a comprehensive view from both migrants and their (Thai) employers. The selection of employers was done through purposive sampling method, taking a variety of work characteristics into account. Table 1 demonstrates the characteristics of the ten selected migrants and four employers who agreed to participate in this study.

|

Table 1 Characteristics and Health Status of Migrant and Employer Interviewees |

Data Collection

Data collection was performed by in-depth interviews with ten local migrants and four employers during October 2014 to September 2015, the period right after the implementation of the OSS. Each informant was interviewed for about two to three rounds until the data were saturated. The first interview started with an informal discussion to enhance rapport. The following interviews then went into more depth and followed emerging discussion points. The interviews were conducted in either Thai or Myanmar or any preferred language of the informants. In order to mitigate a sense of coercion (unintentionally originated by the research team), the interview group was kept as small as possible (normally only the main interviewer and a note taker). Each interview lasted about 30–45 minutes and took place at the interviewees’ household. Telephone interview was used instead for some interviewees who were uncomfortable to undergo a face-to-face interview. It is also important to note that some interviews preferred to participate in a group interview rather than an individual interview because some informants reported that they felt more secure to have their family members around while being interviewed. Verbal consent from interviewees was requested before audio recording. All interviews were transcribed verbatim. Tone of voice and laughter were all noted. The following additional procedures were included in order to safeguard the reliability of the translation. Professional interpreters were asked to verify the correctness of the translation between audio records and transcripts. For the question guides, key informants were asked to describe their experiences of obtaining health-care services as well as their perception and relationship with HICs and other policies concerned with migrant health. The question sets built upon a notion that the health-seeking behaviour of migrants and perceptions of the policy is vastly affected by factors such as the cost of services, and support from peers and family members. This does not necessarily align with the policy’s initial objectives.

Conceptual Framework

The study’s framework recognized two stages of policy including policy formulation and policy implementation phases; but for this study, the latter phase is the main focus. The agenda setting phase during policy formulation was explained in Kingdon’s model21 that when the agenda is set, the objectives of the policy are then translated to the policy implementation stage. In this phase, the Street-Level Bureaucracy theory of Lipsky22 elucidates that policy adaptation is inevitable at all levels of implementation. The adjustment is made to suit the policy users’ circumstances which can unintentionally twist the original policy intention. Additionally, health seeking behaviour among service users also plays a critical role in determining whether the health insurance policy has reached its ultimate goal. Health seeking behaviour determinants as adapted from Maxwell et al23 include three themes: namely (i) individual factors such as current health status and demographic profiles; (ii) system factors which refer to the existing health-care system and health policy; and (iii) societal factors referring to the physical and social environment and support. All mentioned theories were captured and modified in the conceptual framework (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2 Conceptual framework. |

Data Analysis

Data were imported into the NVIVO v10 and coded manually. Inductive thematic analysis was applied. The researcher performed data cleansing of the transcripts using audio records. Condensed meaning units were then labelled by grouping paragraphs and sentences with the same content. Similar meaning units were given preliminary codes and then alike codes were assembled to identify emerging categories. Lastly, the researcher highlighted a higher construct/theme that was demonstrated throughout all categories. The interview data were triangulated with the document review, field notes and memos.

Ethics Consideration

Since International Health Policy Program (IHPP) is a small-sized organization, the commitments do not cover ethical consideration to avoid any possible conflict of interest. Thus, the process for obtaining ethical approval requires an external institution with a high credibility. The Institute for Development of Human Research Protection in Thailand is a recognized institution that aims to protect rights, dignity, safety and well-being of participants in a research which is complied with international standards including Declaration of Helsinki, WHO GCP Guidelines and so on.

This study received ethics approval from the Institute for Development of Human Research Protection in Thailand (IHRP letter head: 166/2558) which is complied with the Declaration of Helsinki. All data remained anonymous including transcripts, data entry and publications. The research team assured total confidentiality of the data to interviewees and advised that it is understandable and acceptable to withdraw from the study at any time or decline to answer any questions. Verbal consent including consent to quote the participants was received instead of the gold standard of written consent since the written consent might cause migrants (particularly those with precarious legal status) to feel distress. All verbal consents were informed verbal consents and approved by the Institute for Development of Human Research Protection in Thailand. A souvenir (costing about US$ 8–15 each) was given to each migrant interviewee as an appreciation present.

Results

A total of five themes emerged from the interviews with ten migrant service users and four employers. The headings of each theme were: (i) Individual factor: different recognition of the insurance card’s function; (ii) Individual factor: equivocality of employment status; (iii) Societal factor: support of family members, employers and peers; (iv) System factor: impression of the insurance card and related-health policies; (v) System factor: struggles in managing the insurance for migrant employees. Note that, when mapping the above conceptual framework, some themes were classified as individual factors, while some were classified as either societal factors or system factors. Details of all five themes were as follows.

Theme 1—Individual Factor: Different Recognition of the Insurance Card’s Function

Of the ten migrants being interviewed, seven were insured with the HICS. There were various reasons for acquiring the insurance card. One interviewee (MM3), who was a translator at the health facility, informed that she recognized the benefit of the card and she strived to buy the card every year. Two interviewees (MK2 and MK4) informed that they received the health card through the assistance of intermediaries (brokers), who helped them during the registration as part of the “registration package”. One interviewee (MM6) stated that the health card could save her from being deported by the officials. She also joined the OSS with a belief that the military might arrest her if she was uninsured. Two interviewees (MM4 and MM5) misunderstood that traffic accidents were not covered by the health card despite the fact that they are actually covered. Two out of seven insured interviewees obtained the card after they were sick (MM2 and MM4).

Theme 2—Individual Factor: Equivocality of Employment Status

The OSS was designed to support all unregistered migrants within the country by providing them with the NV and issuing a work permit for migrant workers who had solid employer. However, some migrant workers in the province were involved with the informal sector and some were even self-employed. Thus, the employment status of a migrant was often unclear, and their job description was not always straightforward or in line with the information provided during the registration. MM2 was a 42-year-old unlawful immigrant who had been through the OSS registration and lived in Thailand for more than 20 years. While being a shop owner was not listed as legally permitted work for him and his work permit stated that he was a labourer, he worked as a karaoke shop owner in Mueang district. Technically, the shop was under the Thai employer’s name who charged him a monthly rent of US$ 152 and allowed him to run the shop on behalf of the real owner. Another complicated scenario was demonstrated through MM5’s story who was a 50-year-old migrant and had been living in Thailand for more than 20 years. She did not possess a legitimate residence permit (Tor Ror 38/1). Her hometown was in Myanmar. She travelled into Ranong by boat and every time she came she acquired a “border pass” (Figure 3) from the sea border control.

|

Figure 3 Outlook of the border pass. |

The border pass was an authorized travelling document between border towns with a permission of stay for not more than two weeks. It served as a relaxed border control between two adjacent countries and was issued for tourists or local people only for short business purposes. However, in reality, the interviewee (MM5) stayed in Thailand almost all the time. She always renewed her border pass by crossing back to Myanmar and getting it stamped by border control every two weeks. She earned a living by selling goods to her neighbours. In her opinion, the health card was pricey since she was still healthy and had no need for health-care services. She also considered the process cumbersome since a broker would need to help her acquire a passport and work permit before she could obtain the health card. The last example of an intricate employment status case was a mismatch between a work permit document and actual work status. One interviewee (MM6) had already possessed all necessary documents (a work permit, health card and residence permit). All documents were obtained with the assistance of a broker. However, the name of employer listed in her work permit was not the real employer who hired her to peel shrimps on a daily basis.

Theme 3—Societal Factor: Support of Family Members, Employers and Peers

It was noticeable that migrants living in Kraburi could earn a greater amount of income, had bigger houses and received better support from family members and peers compared with migrants living in Mueang. The NV had already been achieved in three out of four migrant interviewees in Kraburi (MK2, MK3, and MK4). Additionally, all of these three remained in contact with their family and cousins in Myanmar. In contrast, most interviewees from Mueang did not keep in touch with their relatives. An explanation (stated by the interviewees) was that migrants in Kraburi could easily and economically cross a river back to Myanmar (around US$ 2 per head per trip by an unofficial local speedboat). Thus, they travelled back and forth for numerous significant family events. One interviewee (MK2) stated that her employer, a rubber field owner, provided accommodation for her free of charge (except electricity bills). She was not residing with her husband and her one-month-old baby. Her baby was taken care of with support from her cousin who crossed a river from Myanmar to help her almost every day. Support from employers was also distinct in Kraburi district as most rubber owners offered not only higher salaries than in other districts, but also assistance for OSS registration.

Theme 4—System Factor: Impression with the Insurance Card and Related-Health Policies

All insured interviewees expressed that they were pleased with the health services and decent care from a hospital. Two interviewees (MM3 and MM2) also stated that the frontline workers and nurses were less friendly than most doctors they had encountered. Since the doctors at a hospital were always available, the migrants interviewed preferred to go to a hospital rather than a health centre where the services were mostly provided by nurses. They were all impressed with how the HICS could save them healthcare costs substantially. However, their health-seeking behaviour was affected by a waiting time especially among uninsured migrants with minor diseases. Thus, most of them chose to visit a private clinic as a first solution when becoming ill. One interviewee (MK4) explained that she was willing to pay an extra cost at a private clinic (about US$ 15 per visit) to reduce her waiting time for treatment. As a HICS insuree, she commented that it would be better if the card could cover all of her family members. It is also important to note that her background was unique. She had been unofficially married to a Thai man for over ten years and she was registered as the housemaid of her husband in her work permit. She had not obtained Thai nationality yet and this was the reason she bought the HICS instead.

Though all interviewees expressed that the card could significantly reduce their health expenditure, most of them were still doubtful about the benefit of the card and the reasons behind the change of the card price and related regulations over time. All information about the card was received from discussions with neighbours and peers rather than official announcements.

The advantage of the card is if we have surgery or if we are giving birth, we pay only a little (USS 1) … But the policy changed very quickly. We even informed the villagers (about the card), and then the policy changed again, and the villagers came to blame us (for giving wrong information). [MM3]

MK4 also shared her views that most of her migrant peers preferred the HICS to the SSS. A migrant could (and should) switch his/her insured status from the HICS to the SSS when their NV process is completed and/or when he/she changed jobs from the informal to the formal sector. However, in reality, very few migrants and employers wished to change their insurance schemes. They stated that it was because the monthly payment for SSS was much greater than the HICS premium despite the fact that the SSS provided additional benefits to healthcare treatment. Additionally, they also expressed that the reimbursement process was complicated and not suitable for their needs.

The Social Security Office (the governing body of the SSS) told that they will give us the money back when we reach 60 years of age, and also when we die. Who will guarantee that we will receive that money? And they say they will give us 1000 Baht (US$31) when we leave for our homeland. But you must send notice (to the Social Security Office) in advance … Who will know that their cousin will die by next month? Just 1000 Baht! I can collect it by myself. [MM3]

Theme 5—System Factor: Struggles in Managing Migrant Employees’ Insurance

All the four employers (RN_E1, RN_E2, RN_E3, and RN_B1) expressed their unfavourable attitude toward HICS that it should not be a compulsory policy since it was impractical to purchase their migrant employees a service that they could rarely use as their routine jobs was mobile. Specifically, when migrant workers were working with fishery company where they were mostly offshore. Additionally, they mentioned how legalisation of migrant workers could potentially cause them to lose their employees. When migrant workers passed the NV process, they were allowed to move outside their registered area, and this meant that the employers might lose the employees after the registration process was completed. Thus, paying for the insurance and going through all the registration processes when their employees could leave anytime was not a preferred choice for the employers.

I am always against the HICS. I will be OK with it if it is for migrant who works on land and fish docks. I think those seasiders do not have an opportunity to enjoy the service since they are always in other countries. I spent over a million for this insurance while some migrants only worked for me for some time and then they left. I did not even have a chance to collect the fees from them. I think the policy makers did not understand this context … [RN_E3]

Two employers (RN_B1 and RN_E2) also mentioned the red tape of the registration process which drive them to rely on brokers to attain the registration though extra charges incurred.

Nowadays, there emerge new jobs that try to assist employers in the registration process for migrants. Though I had to pay more but it is less burdensome (laugh!). I got charged for 500 Baht per migrant but the registration required various steps and very tedious since there are many people ….that’s why I am OK with paying for brokers. [RN_E2]

Discussion

Overall, this study provides perspectives from and adaptive behaviour of Myanmar beneficiaries towards the HICS, the main insurance policy for cross-border migrants in Thailand. Based on the researchers’ knowledge, this study is probably among the first of studies to comprehensively explore the perception and behaviour of migrants towards the HICS (and related registration policies including the OSS and the work permit issuance). Although the HICS is well recognized in many international platforms as one of a best practices for providing access to health for vulnerable populations, its actual implementation still faces several challenges.24

One of the clear discoveries from this study is that not all migrants conform to the HICS regulation or the OSS registration policy. As presented above, some migrants did not recognise the existence of the HICS and the majority of the interviewees had little knowledge about it. Phaiyarom et al17 conducted research in two border hospitals in Thailand, which are located in migrant-populated areas. The findings highlighted that service utilization of HICS between 2011 and 2015 was significantly lower than usage of the Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS), the main insurance scheme for Thai citizens, for both inpatient (IP) and outpatient (OP) visits. Phaiyarom et al also suggested that the HICS only increased overall OP visit by 1.7%, compared with uninsured migrants; but this effect size was still smaller than the UCS patients (+8.7%)17 (see Supplementary file).

Maxwell et al pointed that knowledge on the existing healthcare system was an important factor that determined the use of healthcare service (and for this research determines the likelihood of obtaining the insurance).23 It was also discovered that migrants in France underutilized health services due to an unawareness of their existence and a lack of familiarity with the health-care system.25

This research also identifies a more sophisticated point, which is that access to the insurance is not merely determined by an individual’s knowledge or perception. It also depends on the design of the system. A clear instance of this is that most migrants (seven from ten interviewees) realized that the HICS was part of the NV registration package and to obtain the HICS, the most common practice is to rely on private intermediaries (or in their language, “brokers”). This preference also occurred among employers to overcome a strenuous effort to complete the registration for migrant employees. The interference of brokers causes the registration cost to soar tremendously. It was noted that some brokers engaged in all employment processes from faking desirable working conditions to producing counterfeit entry documents, and this led to a higher cost during registration processes than through the official route.26 The migrants’ exploitation was an alarming issue, especially when migrants choose to receive brokers’ services regardless of price and do not appreciate how their labour rights are actually better protected by official registration processes.11 This phenomenon clearly contradicts the primary objective of the policy that intends to enrol as many migrants as possible in the insurance.

When the process of obtaining the insurance was not smooth, some migrants opted to leave themselves uninsured and willingly dropped out the system. In contrast, those who acknowledged the benefit of the HICS always found a loophole in the system in order to access the insurance. For example, this study depicts the story of a woman (MM2) who did not possess a legitimate residence permit but somehow was able to access the insurance. The only proof of residence was the travel pass which she renewed from time to time. Another example is a woman (MM6) who did not know the name of the employer listed on her work permit, but for some reason she was able to complete the whole registration process and acquire the work permit as well as the insurance card.

In other words, the process for service users to acquire the insurance card is distorted from the initial policy intention. This policy adaptation occurs not only among migrants and employers, but also among service providers. Suphanchaimat et al highlighted that local providers involved with the HICS also adapted their routine practice in a way that matched their work burden and individual perception. For example, some providers decided not to sell the insurance card to migrants who were “seemingly” sick despite a lack of guidelines from the MOPH that ratifies such an action.10 Some healthcare providers introduced this internal policy because they deemed that insuring “seemingly sick” migrants might create a financial risk to them (adverse selection phenomenon). However, some evidence shows that the HICS has generated a positive balance for some health facilities, especially those in Bangkok.27 These incidents are consistent with the Street-Level Bureaucracy (SLB) Theory by Lipsky,22 which suggests that policy modification can appear at all levels along the implementation line. Erasmus elaborates more on this point, suggesting that the adaptation of policy is part of the coping mechanisms of the people involved in the policy.28

There were also a deadlock situation which is not merely confined to the SLB, but is linked to a larger conceptual dilemma about whether migrants with chronic diseases are unable to appreciate the card benefits as equally as healthy migrants. Although most of the interviewees who were insured agreed that HICS insurance could save them health expenditure, some migrants with chronic conditions could not obtain the work permit as they were too weak to be re-hired by an employer. Suphanchaimat et al29 investigated the impact of HICS on out-of-pocket payments (OOP) between 2011 and 2015 in both Ranong Provincial Hospital and Kraburi Hospital and discovered a lower OOP among HICS beneficiaries for both IP and OP costs in comparison with those uninsured migrants. It was also observed that uninsured migrants had to pay tremendously more than the HICS insured migrants (2471 Baht or US$ 75) when they got severe conditions that required a hospital admission.29 In 2013, when the HICS included high-cost care in the benefit package, the OOP among HICS beneficiaries became even lower than the previous year and the gaps in the OOP between insured and uninsured migrants became more remarkable as well.29 As a result, service utilization from HICS in 2013 and 2014 soared higher to the point where it was even marginally higher than the UCS.17 This highlighted not only the HICS’s success, but also a policy gap that occurred when an unhealthy migrant could not obtain a work permit and thus, the care they needed.

As highlighted in an earlier study, the government ties the health insurance (HICS) with a work permit to promote both work rights and health protection at the same time.10 Yet this mechanism comes with an unintended consequence in that it practically creates a dead-end circumstance for vulnerable migrants. Leaving unhealthy migrants uninsured is more likely to bring about serious negative consequences than insuring them from the outset. The negative consequences are not just the impact on the balance sheet of a health facility but also the impact on health security for the whole of society, which might be particularly apparent during an outbreak.30 The World Economic Forum has recently expressed concern over the world’s migrants who have no financial resources and supportive health insurance as this could be devastating if countries are unable to take precautionary measures with an entire population during a pandemic.31 Stimpson et al32 also marked that it was necessary to protect public health from uncontrolled pandemics with a feasible option for unauthorized migrants to obtain health insurance that provides prevention and treatment of infectious diseases. In Germany, health insurance for migrants is tied with work and residence status. This means undocumented migrants need to apply for a health card first before enjoying the right to health-care services.33 In Germany a Law of Infectious Disease allows undocumented migrants to obtain free screening and counseling for certain diseases without a requirement to disclose their identity and working status to health-care providers.33 In France, emergency care is freely offered to all migrants regardless of their immigration status for the first three months of their stay. In the meantime, the French government established a special fund to cover unpaid debts of health facilities caused by providing emergency care for uninsured migrants.33

The adaptive behaviours of migrants appear not only among migrant populations. Suphanchaimat and Napaumporn34 report that there was a Laotian immigrant who undertook a registration more than five times and possessed five passports despite the fact that she only needed to complete the registration once. This sort of policy adaptive behaviour also appeared among users of other health policies.

It is also interesting to explore further whether these challenges in policy implementation are reported back to the central authorities (particularly the MOPH) so it can fine-tune and improve the HICS; and this point can serve as a recommended topic for further studies. The case stories above (indirectly) indicate the incoherence between ministries, especially the MOPH and the MOL. It means that the data between both ministries are not synchronized. In theory, those obtaining a work permit should be insured for their health concurrently. In other words, it means that that health and labour protection does not go in tandem.

In terms of policy implication, the HICS design should be reviewed to capture all the dynamics of migrant policies and behaviour of migrants in Thailand. HICS registration (as well as the OSS) should be simplified and free from unnecessary interference by private intermediaries in order to reduce financial barriers that hinder access to care and the NV process. In addition, this study points to a larger question of whether the Thai government is ready and willing to take care of undocumented migrants who do not have equivocal employment status or who fail to take part in the NV process. If so, the HICS alone might not be able to fully address this problem as it is still linked to the registration process, where in reality there will be always people who slip out of the system. In this respect, the Thai government may consider introducing a parallel health service system which allows (unregistered) undocumented migrants to enjoy services. However, this proposal creates a circular logic concerning who will bear the cost of care, and Innovative financing systems need to be considered and perhaps such measures go beyond the responsibility of a single country. All these recommendations should be seriously considered and all concerned parties (the government, migrants, employers and academics to name but a few) should be able to take part in the policy design from the outset.

There remain some limitations in this study. Firstly, the study site was only performed in one province, which is the main residential area for most Myanmar migrants in Thailand. Although Myanmar migrants constitute the largest share of all non-Thai nationals, it is still questionable if the findings can be generalized to all migrants in other areas in Thailand. However, the discovery shown in this study might be, to some extent, transferable to other countries with a relatively similar context to Ranong. Secondly, implications from the findings were made from the interview results rather than actual behaviour observed by the investigators. The interviewers attempted to triangulate the study validity by various means such as informal discussions with local providers or community leaders. Thirdly, the small number of respondents could limit the ability of the study to capture all possible challenges in implementing the policy. It is likely that the investigators missed “the most vulnerable of the vulnerable” such as a totally undocumented migrant with chronic diseases living in faraway village that cannot be identified by the local health staff or NGOs. Lastly, this study focuses on the views and behaviours of the migrant service users only. To gain a better understanding on the HICS in all dimensions, it is necessary to take a thorough view from all stakeholders’ perspectives including policy makers, service providers, donors, civic group representatives and academics. Therefore, the interpretation of the findings should be made with caution and if there are points to be considered for policy for recommendations, the views from other stakeholders should be seriously taken into consideration.

Conclusion

Health insurance for migrants allows them to enjoy their human right to access essential care regardless of ethnicity. The migrants’ and employers’ perspectives on and responses to the Health Insurance Card Scheme (HICS) in this study reflect the challenges faced in policy implementation. Due to the lack of familiarity with the policy, migrants were unaware of the benefit they could claim in obtaining the health card. This reflects how their rights were not clearly communicated and promoted. Migrant exploitation is another alarming issue, and it is evident that brokers create opportunities during confusing registration process resulting in a costlier process than necessary. Policy intention distortion and adaptation to suit actual situations and individual justifications appeared among both service providers and user’s responses as part of the policy engagement mechanism. Unhealthy migrants are possibly unable to benefit from the policy as much as healthy migrants due to the lack of alternative pathways for them to obtain the service economically. Public health concerns over a control of infectious diseases among unauthorized migrants who have no access to health services are flagged as a threat that need to be resolved strategically. Policy recommendations emerging from the findings can be summarised into four main points. Firstly, the benefits of HICS and official registration processes for migrants should be vividly and correctly communicated and promoted by local authorities to avoid both underuse of health insurance and broker interference. Secondly, cumbersome and time-consuming registration processes could be resolved in order to close gaps for broker interference. Thirdly, migrants with chronic conditions and unauthorized migrants should be taken into policy design considerations in order to protect public health. Lastly, feedback channels from the ground to central levels are also indispensable in order to accumulate and resolve implementation dilemmas and this should be further examined.

Acknowledgments

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library. All authors would like to express great appreciation toward local workers, migrants’ interviewees and IHPP members who accommodated the data collection process. There is also a high appreciation toward some data from the doctoral thesis of Dr Suphanchaimat. It is noted that the analysis and writing style was not uniquely the same as presented in the thesis. For instance, some more references that were not contained in the thesis were included. Enlightening guidance and advice from LSHTM staff, especially Prof. Anne Mills, are immensely thankful.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

1. Aldridge RW, Nellums LB, Bartlett S, et al. Global patterns of mortality in international migrants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;392(10164):2553–2566. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32781-8

2. United Nations. International Migration Report 2017 Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/404) United Nations. New York, NY, USA: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; 2017.

3. Koser K, Laczko F. World Migration Report 2010: The Future of Migration: Building Capacities for Change. Geneva: International Organization for Migration; 2010:115.

4. World Health Organization. 60th Assembly. Resolution WHA60. 26-Workers’ Health: Global Plan of Action. Resolution WHA6026. Geneva: WHO; 2007:8.

5. World Health Organization. 61st Assembly. Resolution WHA61.17 – Health of Migrants. Resolution WHA6117. Geneva: WHO; 2008.

6. Macpherson DW, Gushulak BD, Macdonald L. Health and foreign policy: influences of migration and population mobility. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(3):200–206. doi:10.2471/BLT.06.036962

7. United Nations. Global Compact for Migration United Nations. New York, NY, USA; 2018. Available from: https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/migration-compact.

8. World Health Organization. 72nd Assembly. Resolution WHA70.15- Promoting the Health of Refugees and Migrants. Resolution WHA7015. Geneva: WHO; 2017.

9. Tangcharoensathien V, Mills A, Palu T. Accelerating health equity: the key role of universal health coverage in the sustainable development goals. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):101. doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0342-3

10. Suphanchaimat R, Pudpong N, Prakongsai P, Putthasri W, Hanefeld J, Mills A. The devil is in the detail-understanding divergence between intention and implementation of health policy for undocumented migrants in Thailand. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(6):1016. doi:10.3390/ijerph16061016

11. International Organization for Migration. Thailand Migration Report. 2019:2019

12. OECD/ILO. How Immigrants Contribute to Thailand’s Economy, OECD Development Pathways. OECD Publishing; 2017.

13. Suphanchaimat R, Putthasri W, Prakongsai P, Tangcharoensathien V. Evolution and complexity of government policies to protect the health of undocumented/illegal migrants in Thailand - the unsolved challenges. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2017;10:49–62. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S130442

14. Health Insurance Group. Health card for uninsured foreigners and health card for mother and child.

15. The World Bank. GDP per capita (current US$): the World Bank; 2013 Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD.

16. National Council for Peace and Order. Temporary measures to problems of migrant workers and human trafficking (Order No.118/2557). Report No.: 118/2557. Bangkok: NCPO; 2014.

17. Phaiyarom M, Pudpong N, Suphanchaimat R, Kunpeuk W, Julchoo S, Sinam P. Outcomes of the health insurance card scheme on migrants’ use of health services in Ranong Province, Thailand. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):4431. doi:10.3390/ijerph17124431

18. Ranong hospital. Overview of Migrant Utilisation in Ranong Hospital. province SvoBoHAiR, editor. Ranong, Thailand: Ranong hospital;2014.

19. Srivirojana NPS, Robinson C, Sciortino R, Vapattanawong P. Marginalization, morbidity and mortality: a Case Study of myanmar migrants in Ranong Province, Thailand. J Popul Soc Stud. 2014;22(1):33–52.

20. National Statistical Office. Population and Housing Census. Bangkok: NSO; 2008. Available from:: http://statbbi.nso.go.th/staticreport/page/sector/th/01.aspx.

21. Kingdon JW. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies.

22. Lipsky M. Street-level bureaucracy: dilemmas of the individual in public services. Polit Soc. 1980;10(1):116.

23. Maxwell AE, Bastani R, Glenn BA, Taylor VM, Nguyen TT, Stewart SL. Developing theoretically based and culturally appropriate interventions to promote Hepatitis B testing in 4 Asian American Populations, 2006–2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E72. doi:10.5888/pcd11.130245

24. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The 3rd global compact for safe, orderly and regular migration stakeholder workshop. 2018. Available from: http://www.mfa.go.th/main/en/news3/6886/86125-The-3rd-Global-Compact-for-Safe,-Orderly-and-Regul.html.

25. Priebe S, Sandhu S, Dias S, et al. Good practice in health care for migrants: views and experiences of care professionals in 16 European countries. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):187. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-187

26. Suphanchaimat R, Pudpong N, Tangcharoensathien V. Extreme exploitation in Southeast Asia waters: challenges in progressing towards universal health coverage for migrant workers. PLoS Med. 2017;14(11):e1002441–e. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002441

27. Srithamrongsawat S. Financing Healthcare for Migrants: A Case Study from Thailand. Nonthaburi, Thailand: Health Insurance System Research Office/ Health Systems Research Institute; 2009.

28. Erasmus E. The use of street-level bureaucracy theory in health policy analysis in low- and middle-income countries: a meta-ethnographic synthesis. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(Suppl 3):iii70–8. doi:10.1093/heapol/czu112

29. Suphanchaimat R, Kunpeuk W, Phaiyarom M, Nipaporn S. The effects of the health insurance card scheme on out-of-pocket expenditure among migrants in Ranong Province, Thailand. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2019;12:317–330. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S219571

30. Mosbergen D. COVID-19 Surge Exposes Ugly Truth About Singapore’s Treatment of Migrant Workers. Huffpost; 2020.

31. World Economic Forum. The coronavirus pandemic could be devastating for the world’s migrants: world economic forum; 2020 Available from: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/the-coronavirus-pandemic-could-be-devastating-for-the-worlds-refugees/.

32. Stimpson JP, Wilson FA, Su D. Unauthorized immigrants spend less than other immigrants and US natives on health care. Health Aff. 2013;32(7):1313–1318. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0113

33. Gray BH, van Ginneken E. Health care for undocumented migrants: European approaches. Issue Brief. 2012;33:1–12.

34. Suphanchaimat RaN B. Well-Being Development Program for Alien Health Populations in Thailand (Phase I). Nonthaburi: HISRO/IHPP/The Graphico Systems Co. Ltd.; 2015.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.