Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 10

Perspectives Of Health Professionals And Educators On The Outcomes Of A National Education Project In Pediatric Palliative Care: The Quality Of Care Collaborative Australia

Authors Donovan LA , Slater PJ , Baggio SJ , McLarty AM , Herbert AR , (QuoCCA) QOCCA

Received 17 June 2019

Accepted for publication 4 October 2019

Published 7 November 2019 Volume 2019:10 Pages 949—958

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S219721

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Leigh A Donovan,1 Penelope J Slater,2 Sarah J Baggio,3 Alison M McLarty,3 Anthony R Herbert3,4

On behalf of the Quality of Care Collaborative Australia

1Bereavement Service, Queensland Children’s Hospital, Children’s Health Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia; 2Oncology Services Group, Queensland Children’s Hospital, Children’s Health Queensland, South Brisbane, QLD, Australia; 3Paediatric Palliative Care Service, Queensland Children’s Hospital, Children’s Health Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia; 4Centre for Children’s Health Research at Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Correspondence: Penelope J Slater

Oncology Services Group, Queensland Children’s Hospital, Children’s Health Queensland, 12b, 501 Stanley St, South Brisbane, QLD 4101, Australia

Tel +61 7 3068 5785

Email [email protected]

Purpose: Demand for generalist health professional knowledge and skills in pediatric palliative care (PPC) is growing in response to heightened recognition of the benefits of a palliative approach across the neonatal, pediatric, adolescent and young adult lifespan. This study investigates factors that enhanced PPC workforce capability and education outcomes in metropolitan and regional areas through the integration of dedicated educator roles within specialist pediatric palliative care (SPPC) teams through a national education project.

Methods: Cross-sectional, prospective qualitative study guided by the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies. The study drew on Discovery Interview methodology and transcripts subjected to inductive thematic analysis. A convenience sample (n=16) of health professionals and educators were recruited from specialist tertiary and regional services providing PPC in Australia.

Results: Four themes emerged related to outcomes of the national PPC education project: (1) building capability in PPC, (2) developing inter-professional partnerships, (3) sustaining staff well-being, and (4) learning from children and families. Dedicated educator roles in SPPC services enhanced workforce capability through education and ongoing mentoring, built collaborative relationships between the complex network of care providers for children with a life-limiting condition (LLC) and their families, and improved quality and access to PPC. Delivery of education evolved from didactic to interactive engagement and coincided with development of a mentoring model between SPPC clinicians and generalist health and social care providers.

Conclusion: This study contributes to a growing body of knowledge on innovative and responsive mechanisms for enhancing workforce capability in PPC and provides additional evidence to support funding of dedicated educator roles in specialist PPC services.

Keywords: health professionals, education, workforce capability, pediatric palliative care

Introduction

Pediatric palliative care (PPC) services have evolved in response to the diverse and often complex needs of children and young people diagnosed with a broad range of life-limiting conditions. In Australia, estimates suggest 32 per 10,000 children (0–19 years) may benefit from a palliative approach.1 PPC embraces a holistic approach to care “of the child’s body, mind and spirit” and also acknowledges the role and support needs of the child’s family.2 PPC is now recognized as a mainstream sub-speciality in Australia with specialist pediatric palliative care (SPPC) services based in seven tertiary children’s hospitals, offering holistic care delivered by an interdisciplinary team of health professionals (HPs).3

Family centered care is a core principle of PPC whereby the child, family, and health care provider work in partnership to meet the ever-changing physical, psychosocial, developmental, emotional, spiritual, and practical needs.4 The principles of PPC now extend from a neonatal diagnosis through to transition to adult care. In contrast to adult palliative care, it is not uncommon for a child referred to PPC to continue to live for months or years. In response to this extended illness trajectory, meeting the needs of the child and family in their home and community is a core principle of optimal PPC.5–7 This heightened recognition of the benefits of a palliative approach across the neonatal, pediatric and young adult lifespan has increased the demand for education in PPC for generalist HPs.8,9 The 1:60 ratio of child to adult deaths in Australia necessitates extra support for HPs caring for families for the infrequent PPC cases.10

In 2014, the Quality of Care Collaborative Australia (QuoCCA) project was formed to enhance the knowledge, skills, and confidence of acute and community-based HPs in the principles of PPC.11 The collaborative included representatives from SPPC teams in six tertiary children’s hospitals in Australia. Project education aims were to build PPC capability in local health services providing care for patients and families in their home and/or local community, and to enhance the scope of generalist HPs. A multidisciplinary team of medical, nursing and allied health educators were recruited to the project to develop and deliver an education program throughout Australia.

Participants engaged in either a scheduled general education session in a metropolitan, regional, or rural health site or “pop-up” education and mentoring focused on a specific patient and family’s needs. The “pop-up” model of care evolved at children’s hospitals in New South Wales, whereby “just in time” learning was delivered by members of the SPCC team in regional and rural communities via face to face, teleconference or telehealth (videoconference).3 The aim of the pop-up model was to build capability of local health providers to ensure a child and family could remain in their home or community throughout the child’s illness trajectory.3,11,12 From May 2015 to July 2017, over 5770 health and human service professionals throughout Australia received education through the first funded QuoCCA project, with both novice and experienced PPC providers improving their knowledge and confidence.13

This descriptive study adopted Discovery Interview methodology to explore the perspectives and experiences of QuoCCA educators and HPs working in SPPC services in Australia. The aim was to identify factors that enhance PPC workforce capability and education outcomes through the integration of dedicated educator roles within SPPC teams.

Materials And Methods

Study Design

This descriptive study was conducted by members of the lead QuoCCA site based in Children’s Health Queensland (CHQ) (PS, LD, SB) and guided by the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ).14 The study utilized Discovery Interview (DI) methodology to explore the perspectives of QuoCCA educators and HPs working in specialist tertiary and regional services providing PPC in Australia.

DI methodology was developed by the National Health Service, United Kingdom, as a service improvement tool and patient involvement mechanism for progressing patient-centered services.15–17 Previous evaluation at CHQ demonstrated benefits in this methodology for exploring families’ needs and improving their experience.18 DIs consisted of a one-to-one, open interview technique that enabled the collection of detailed experiences of participants with the content driven by the interviewees.15,17

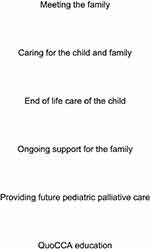

Three QuoCCA staff in the lead site (CHQ) were trained in undertaking DIs and used a “spine” to guide the interviewer through their story based on key stages of consumer’s experience of the service17 (See Figure 1). The interviewee could use this spine as a prompt to facilitate them to tell their story and talk about whatever they felt was important in those areas in the journey of being a health professional or an educator in PPC, without being limited to topics that may be presented in a series of pre-set questions. Probing questions were kept open and did not guide the interviewee down any particular path. The protocol for this project was approved by the Children’ Health Queensland Human Research and Ethics Committee (HREC/16/QRCH/55).

|

Figure 1 QuoCCA Discovery Interview spine for health professionals. |

Participants

HPs providing PPC and QuoCCA educators in Australia were recruited through a convenience sample.

Data Collection

A DI was undertaken with each of 16 educators and HPs working in PPC between March 2016 and December 2017. The subjects were chosen via a convenience sampling technique, where the educators and HPs were consenting and accessible. As per the Ethics approval, interviewees were excluded if they were less than 18 years of age or had a cognitive impairment, intellectual disability or a mental illness. Interviews were conducted by the QuoCCA Project Advisor (PS) (n=14) or the Allied Health Educator (SB) (n=2) in a quiet meeting room at the participant’s workplace (n=15), or via telephone (n=1), and averaged 43 mins. The interviewee was taken through an information sheet and consent form, which was signed, and instructions given about how to revoke an interview from the pool. Interviews lasted anywhere between 30 mins and 2 hrs, as guided by the interviewee, and were audio-recorded. Interviews were transcribed by a professional transcription service and de-identified (for patient, family, clinicians, and location).

Data Analysis

To align with the intention of the DI methodology an inductive thematic analysis was conducted by two investigators (PS, LD).19 This methodology ensures the voice and experience of individual participants is retained while simultaneously allowing for collective themes. The DI methodology was not designed to provide a representative sample but to discover insights into the family’s experience that cannot be gained in other approaches. Even one interview was a rich resource for the service team to develop service improvements.

Transcriptions were uploaded and analyzed through Dedoose Version 8.0.3520 drawing on the phases described by Braun et al: generating initial codes through immersion in the data; sorting codes into sub-themes; refinement of themes; and finalizing a thematic map of the data.21 At each stage, investigators met to assess similarities and differences in analysis until consensus was reached on 100% of the themes.

Results

Sixteen participants (n=8 HPs, n=8 educators) represented services in five Australian states. The greater proportion were metropolitan-based (81%) with half holding a substantive role in nursing. Medical and nursing staff held substantive positions in SPPC, Oncology, Connected Care, and Pediatrics. Participants from an allied health discipline had a diverse range of professional backgrounds (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Discovery Interview Participant Details (n=16) |

Four themes, and related sub-themes, emerged as core to the experience of HPs and educators following the implementation of the QuoCCA project.

Building Capability In PPC

Transitioning To PPC Educators

Educators made the transition to this new role following extensive clinical experience in PPC. On reflection, educators suggested this transition could be enhanced by associated professional development in adult learning principles and training in the use of simulations and technologies such as telehealth and webinars.

They might be really good at their job but they might not have the [education] skills. HPE005

HPs described the challenges of balancing a clinical and educator workload. The implementation of QuoCCA educator roles in PPC meant that a dedicated role existed within the team to collate resources, coordinate and deliver education, and contribute to the national education program. A secondary benefit of the educator role was the capacity to focus on enhancing the knowledge, confidence, and well-being of clinical staff. In turn, clinical staff described a positive impact on the experience of caring for the child and family.

It’s great to have [the educator] as … an external person to the team … with fresh eyes … and she can see things that we can’t and she has the time and ability to meet … the education of staff or support of staff … which ultimately really impacts on the way that the staff care for the child and their family. HPE002

Throughout the evolution of QuoCCA, state-based educators described developing strong national collaborative relationships based on their shared passion and goals. These relationships were enhanced through national planning meetings and regular teleconferences where resources and learnings were shared and innovative education techniques developed. Strong collaboration meant the translation of learnings between educators and harmonization in content and delivery of education throughout Australia.

The biggest thing for me is the relationship building with other nurse educators and CNCs [Clinical Nurse Consultants] in other states. Being part of their workshops, listening to how they teach; they are a wealth of knowledge … all the lightbulbs go on … the sharing of resources and the brainstorming [was] confidence building. HPE005

Providing Effective Education

Teaching styles were adjusted as educators gained confidence in their new roles and received feedback on education delivery. Traditional didactic teaching methods evolved into more interactive and innovative teaching models.

I think early on when we were finding our feet it was very much didactic because we had to learn it ourselves … you can become a little bit more engaging once you’re comfortable. HPE011

Educators quickly observed that participants in the education program brought with them a wealth of knowledge, skill, and expertise. Humbly recognising this became an asset for educators and contributed to the development of a shared and flexible learning experience between themselves and participants.

You really want to increase the capacity, but respectfully. It’s a matter of, we might be the specialist palliative care team, but they’re the people that are there. HPE005

Interactive teaching and learning methods provided a vehicle for educators to share their lived experiences of clinical practice. Educators found the impact of education particularly improved when aligned with the learning needs of participants. For example, communication around ‘tough conversations’ was a topic that many HPs sought, and those sessions allowed them to learn and practice the necessary skills to increase their comfort level.

The more experience and the more contact they can have and the more education they can get, to try and increase their comfort level … it should be mandatory education for pediatric nurses to have so that they can get that comfort with the parents and the children and not shying away from the tough conversations. HPE012

Making Education Accessible

Given the small proportion of PPC patients that regional HPs care for, many could not rationalize attending longer education sessions.

I just can’t get people interested in doing longer hours of formal education out in the community, it’s such a small part of their remit - pediatric palliative care is so rare and they just can’t justify that time away. HPE006

HPs described the pop up model of education as a more innovative way of engaging the network of support in the family’s community when PPC was required by a specific local patient. Local teams were appreciative of the time, care, and support provided by specialist palliative care educators and this relationship then extended beyond the initial visit.

I think people feel a lot more comfortable having education in their own environment and they’re more open and it’s easier to attend things. HPE001

In turn, families had the opportunity to meet the SPPC team in their own community and build a relationship that could continue via telephone or video-conferencing. The SPPC team found meeting the child and family in their home environment allowed for a more intimate understanding of their day to day functioning and associated needs.

It was fabulous, having them here for the two days … Mum and Dad [of sick child], really sung the praises of having that face to face in their own home … people they had talked to on the 1800 number … being able to picture faces of the team and seeing the care and the attention they gave them there on the day … it was just a really, lovely meeting … full of positives. HPE012

Educators could respond to the challenges of the geographical size and remoteness of many areas in Australia by creating an online portal of resources and education modules that could be accessed as needed by non-specialist team members.

Having that link with CareSearch22 is a really good start, some online resources and modules, so at 2am in the morning or when the community nurse needs it, it’s there. HPE001

Developing Inter-Professional Partnerships

Navigating The Complex Web Of Formal And Informal Care Providers

Participants described the complex care needs of the child and family which required a diverse network of health and social care professionals. Educators and specialist HPs reported learning to identify the multiple layers of care to ensure inclusivity when engaging care providers in the family’s local community.

We had one particular [visit] where we went to the school, a hospital, the carer agency … then we had a big family meeting with the family. It made me realise, it’s just so complicated … there are so many people you have to think about. It’s not just about giving them a symptom management plan and some morphine. HPE015

Educators and HPs described the QuoCCA project as a valuable mechanism for developing a consultative relationship with community-based care providers and primary care teams.

As our [patient] numbers have grown, but our staff or funding hasn’t, we’ve had more of a consultative role. The only way we can move from a care co-ordination to a consultative model is educating other health professions on what palliative care is, how we can help and how best we can work together working alongside that primary team. HPE014

Providing PPC in the local community also meant the development of partnerships between all care providers and a reduction in professional isolation which participants suggested enhanced outcomes and resulted in more integrated care for all stakeholders.

None of us do this work in isolation, we can’t. There’s specialty units we have to partner with. So, we have to work out good ways of making sure that they are as educated and supported as possible. Preparing local teams and educating people counts because it makes it work. HPE013

Establishing Communication Pathways

Participants suggested dedicated educators had integrated more fully into local communities through scheduled and pop-up education, and enhanced effective communication between the tertiary specialist service and regional services. This also encouraged earlier referrals to the specialist service.

Before [the QuoCCA educator] went out there our contact was quite haphazard. They [primary care team] wouldn’t come and speak to us directly … they would make decisions locally. Once [the QuoCCA educator] went out there the lines of communication were really open and we were able to support them to support the family much better. HPE002

Education sessions were operated under the principle of respect for the child’s primary care team that then demystified the SPPC role, enhanced relationships, and established trust between SPPC teams and primary care teams.

One of the biggest frustrations of my job, I would say, is that I’m not here to you do your job, I’m not here to tread on your toes, but me having these conversations with mum in the corridor or me seeing them when they come into hospital actually builds a relationship that we can use at the end of life; and trust, it builds trust. HPE005

On arrival in the families’ community, educators learned to arrange a “pre-huddle” with the primary care team prior to meeting with the family. This strategy helped clarify the objectives of the meeting which was paramount in the lead up to potentially difficult conversations around advanced care planning, resuscitation planning, and unexpected change in a child’s health trajectory.

Before you go into the [family] meeting I always encourage a pre-huddle. Talk with your team [about] who might lead. Especially if it’s going to be quite a difficult conversation, and work out what is the objective of the meeting. I’ve gone with another team, and they’ve had a totally different agenda. HPE015

Enhancing Capability Throughout Mentoring Relationships

As the project evolved, participants perceived a growth in the PPC workforce in regional and rural locations. HPs with experience in adult palliative care developed skills, knowledge, and confidence in PPC.

We can’t keep up with the amount of enquiries that we are getting in regard to more adult palliative care services who don’t have the education or experience in pediatrics … rather than create another workforce … we can empower a workforce who are already doing palliative care to provide pediatric care. HPE014

One educator described QuoCCA as having a dual focus: delivery of education followed by ongoing collegial support and guidance. Educators described mentoring local teams by providing the necessary initial information, identifying any gaps, modeling care provision and interactions with the child and family during collaborative home visits and remaining available for ongoing support.

I also like to talk to the people doing the hands-on … checking that they are okay … some self-care and reflection … if I’ve been involved with particular nurses, I go back and check in with them. Because I think I’ve got to model and mentor what I want others to [do]. Because I’ve seen more and more nurses exhausted and burned out. HPE015

Sustaining Well-Being In PPC

Sustaining Emotional Well-Being

Educators and HPs affirmed that sustaining well-being was essential and adopted a range of self-care strategies such as maintaining professional boundaries, good physical and emotional health, and making time for themselves and with their own family.

Some days you go ‘why the hell am I doing this’ because it’s so gut wrenching … sad and heavy … but it is a privilege that we do sit in this space where people have a real trust in us quite immediately and it’s important that we don’t forget that … these people are really vulnerable. HPE008

Participants acknowledged the heightened emotional response they experienced in various situations such as introducing the concept of palliative care to a family for the first time and feeling a need to “get it right”.

When you’re meeting a family for the first time can be one of the biggest stress points than the job itself … particularly if you’re an experienced clinician because your vision for what’s going to happen for them is already in place; it can be quite devastating meeting a family for the first time who has no idea what’s going to happen to them. HPE013

Some participants described their long-term care of a child and the grief experienced following the child’s death. Staff found opportunities to temper their grief by attending a child’s funeral and reflecting on the end of life care experience through death reviews. Others reflected on their experience of parenting their own children and the risk of hyper-vigilance.

When a child does die who I’ve known for quite some time … I found it really challenging. I didn’t know who I could speak to. I caught up with some of the nurses. They attended the funeral, and kept me in the loop … We have a buddy system, because all of allied health was fairly involved … we’d catch up over coffee, and debrief about it, and I found that to be really worthwhile. HPE011

Finding Meaning And Purpose

Knowing that their help and support made a difference to families contributed to HPs sense of professional purpose and meaning.

It’s highly valuable work. … it’s important that we get it right because parents and families, the kids that grow up and have their generational bereavement … they look back to this time and they never forget a good memory of staff being supportive and helpful. That’s my whole aim and the reason why I’m so passionate about … getting it right for these parents and families. HPE009

Funding dedicated educator roles enabled capacity for SPPC team members to enter families’ homes which in turn meant a heightened understanding of the family and a sense of holistic health care.

I particularly like meeting families in their home. This is the one job where I believe as nurses we actually get to practice holistic care … it starts with meeting families in their homes and seeing their photos and seeing their toys and seeing their family pets. HPE008

Educators commented on the relevance of supporting the primary care team who in turn provided direct support for the family. It appeared equally rewarding to walk alongside primary care staff who had less experience in PPC and share knowledge and practice wisdom enabling a high-quality service for the children and families in their own community.

If I can support the family in any way that made their life a bit easier, then that’s what I get out of it. It doesn’t have to be me directly talking to them, it can be supporting the team and that’s what gives me comfort. HPE005

Finding Your Support Network … Find Your Tribe

A supportive team culture was described as core to maintaining resilience in PPC. Participants reflected on a range of team strategies that were encouraged and modeled through QuoCCA visits including informal “checking in” with staff, supporting each other’s self-care strategies, clinical supervision, joint home visits to provide support for other staff, debriefing and team reflection.

I was up on the ward with the nurse … she had looked after a patient that died just a couple of days before … and I said, “And how are you?” And then she just started crying. She was just sad, and she couldn’t sleep at night, she kept thinking about this family, and – and I thought we don’t actually look after them and nurture them. Now I go back and check if they are okay … because I think I’ve got to model what I want others to do. HPE015

Some teams had embedded regular team supervision, and one participant describing the positive impact of having a professional space to talk about their experiences, express what they were feeling, and articulate what support they needed.

We do a what we call clinical supervision as a team, and we have someone come in, and we talk about cases, or particular issues that have come up. I find that extremely helpful, because it’s really an honest space. We all do it together. We all cry sometimes. And we’re all honest. HPE015

Learning From Children And Families

Providing Family Centered Care

Participants acknowledged family centered care was integral to good PPC. Experienced care professionals had learned to walk alongside the family at their pace, sustain the child’s developmental goals, and empower families to retain a sense of control in decision-making around end of life and location of death.

At the end of life you want them [family] to be able to look back and hope that they’ve done everything that they wanted to do with their child. It’s making sure they are comfortable in the place they want to be, and if they change their mind, they can move. HPE015

Participants described learning to listen deeply to family stories and demonstrating a common humanity both as ways of sharing with the family “I care”.

Throw out your cookbook recipes of how to counsel people because they don’t care whether you’ve done step 7 [of the counselling process] and enacted advanced accurate empathy; what they care about is whether you care or not … just go in there and be human. HPE009

Conversations With Families

Participants described some families feeling confronted by their perception of what the PPC team represented, while others readily engaged planning for their child’s end of life.

Every time we came it represented what lay ahead. She [mother] just couldn’t stomach us at that time. We were struggling, because we thought the child was getting worse and we wanted to help manage symptoms. But we had to give that family time to grieve and – because we represented what she wasn’t ready to see. HPE015

Participants talked about the importance of HPs giving families time to adjust to their child’s new health trajectory and taking every opportunity to build a trusting relationship between themselves and the family prior to the child’s death.

Every intervention, conversation, even just seeing people by chance down the corridor … every little glimpse that you have, it all builds on people’s perception of [our] willingness or ability to assist or whether they want you to be involved. HPE009

Participants affirmed the importance of HPs feeling confident in integrating conversations around spirituality as a tool to assist families find meaning and purpose in life throughout the child’s often tumultuous health trajectory.

Spirituality is very powerful and it can be really helpful to remember it’s where people can find calm and meaning and purpose and some comfort in dark times. I think it gets forgotten and people can be uncomfortable with that conversation. HPE008

Planning Ahead To Support Families

Collectively, participants affirmed the role that palliative care can have for families longer term. Participants described the power of planning ahead, “getting it right”, and doing everything possible to ensure a good death.

How things evolve for that family is going to impact them for the rest of their lives. If it [child’s death] goes well it’s going to serve them for a lifetime and if it goes poorly, it could have an impact for a very, very long time. HPE001

Participants acknowledged the isolation many families experienced following the death of their child and the supportive impact bereavement care can have on helping families explore ways to recreate meaning and purpose in their lives.

One of the things I try to convey in bereavement counselling is that you’ll never get over the loss … the love and relationship you have with someone that died can never leave you; it’s about reconstructing the relationship to make sense now with them not being physically present, but in a way that’s meaningful to them. HPE008

Discussion

The emergence of PPC as a sub-speciality has required innovation in education and service delivery. This is particularly relevant in Australia where children with a LLC and their families are geographically dispersed and often access generalist local health care providers. The QuoCCA project enabled funding of dedicated medical, nursing, and allied health educators who improved the knowledge and capability of HPs providing PPC throughout Australia.13

Although the QuoCCA program was set up to increase capability through an education framework, the study revealed other positive outcomes that supported staff: the development of partnerships between services, mentoring of staff by specialist services, sustaining staff well-being, and learning from children and families. Traditional education programs worldwide are incorporating models of individual and team mentorship as a way of increasing workforce capability and resilience.23–25 For example, longitudinal mentoring in the USA enabled enduring, interdisciplinary relationships across multiple health care organizations.23 Mentoring emerged through QuoCCA as strong networks were built between SPPC teams and community-based teams encouraging a collaborative service response for children and families. These networks also improved resilience as this additional layer of support enhanced the well-being of HPs.

The successful transition from an expert health professional to educator requires guidance and support. Strong clinical skills may provide a knowledge foundation however do not necessarily prepare clinicians for teaching. Appropriate preparation for the role of educator, having a mentor, learning teaching skills and access to an evidence-based teaching curriculum increases job satisfaction and enhances self-confidence in this new role.26,27 In the nursing context, the inclusion of formal pedagogical education has been recommended into nursing graduate programs, identifying four phases in the development from a clinical nurse to an educator: anticipatory/expectation, disorientation, information-seeking, and identify formation.28

Our study reflects similar educator movement in knowledge, skill, and confidence over time. Participants reflected on the application of adult learning principles such as: acknowledging the experience and wisdom of non-specialist PC providers and/or generalist HPs and incorporating experiential education methods. QuoCCA educators increasingly utilized innovative, evidence-based teaching and learning methods12,29,30 such as role play, simulation, and music, which enhanced learning and led to outcomes such as improved communication pathways and timely referrals to PPC.31

HPs should be upskilled in both cultural capability and cultural safety. QuoCCA education therefore addressed cultural considerations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations including understanding of disease causation, the performance of ceremonies, and the importance of dying on traditional lands. Appreciation of how these patients and families perceive health services and communicating in culturally sensitive ways was also important. Multiple factors can act as a barrier for families seeking services and HPs in providing those services.32

The perspective of HPs in our study affirmed the value of dedicated educator roles in SPPC teams. Workload demands meant challenges in integrating education within a clinical workload. Educator roles extended beyond resource development and targeted education in areas of need. QuoCCA has enabled multi-level change, and growth in the health care system in Australia, however, has been reliant on funding to extend the program throughout the past five years. The goal now will be to sustain this critical education program into the future.

The pop-up model of education has become a critical feature of QuoCCA.3,13 Participants described being able to transgress traditional barriers to education by engaging face to face with formal and informal networks that directly care for a current patient with a LLC and their family. Mezirow and colleagues (1994) coined the term “transformative learning”, a process whereby traditional mindsets and perspectives are challenged to become more inclusive, engage the learner in self-reflection and ultimately social change. The core aims of QuoCCA were to improve the capability of national HPs, improve access to and quality of PPC, and increase community awareness of death and dying in the pediatric population.13 We believe QuoCCA has enabled transformative learning and enabled social action in the context of PPC through these innovative teaching and learning methods.

Limitations

This study incorporates the perspectives of a small cohort of SPCC HPs and educators in Australia at a distinct point in time. While use of descriptive qualitative methodologies enables rich description of the lived experience, results may not be representative of the variety of experiences in differing health contexts internationally.

Conclusion

QuoCCA has enabled rapid change in workforce capability in PPC in Australia, enhanced quality of service delivery and access to PPC in a geographically dispersed population of children with a LLC and their families. This study provides further evidence to support the integration of educators as a standard feature of SPPC teams. Beyond providing education, these roles had an ongoing mentoring function for staff providing PPC outside the specialist services; sustaining wellbeing, building partnerships and enhancing family centred care. Incorporating the voice of families impacted by the QuoCCA program in future research would provide additional evidence to support this innovative education program.

Acknowledgments

This project involved a collaboration of six tertiary pediatric palliative care entities throughout Australia managed through the National Project Lead Entity, Children’s Health Queensland (CHQ) Hospital and Health Service, headed by the National Project Sponsor, Chief Executive CHQ, Fionnagh Dougan. The collaboration included staff from tertiary pediatric palliative care services from Queensland Children’s Hospital, Brisbane, Queensland; Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick, New South Wales; John Hunter Children’s Hospital, Newcastle, New South Wales; Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria; Women’s and Children’s Health Network, Adelaide, South Australia; and Perth Children’s Hospital, Perth, Western Australia. Appreciation goes to the other collaboration members and their supporting agencies, including the QuoCCA Project Leads and Educators from each state - Sara Fleming and Julie Duffield, South Australia; Jenny Hynson and Melissa Heywood, Victoria; Marianne Phillips, Suzanne Momber and Charlotte Burr, Western Australia; Sharon Ryan and Susan Trethewie, New South Wales; and Lee-Anne Pedersen, Jacqueline Duc, and Angela Delaney, Queensland and Project Manager Susan Johnson. Many thanks also to the educators and participants in the QuoCCA education, from both the private and public sector, and those that provided their helpful assistance in undertaking interviews. The QuoCCA Project was undertaken through Australian Government Department of Health funding provided from the National Palliative Care Projects operating under the Chronic Disease Prevention and Service Improvement Fund, grant funding round H1314G012.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Fraser LK, Miller M, Hain R, et al. Rising national prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children in England. Pediatrics. 2012;129(4):e923–e929. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2846

2. Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A. Palliative care: the World Health Organization’s global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2002;24:91–96.

3. Mherekumombe MF, Frost J, Hanson S, Shepherd E, Collins J. Pop up: a new model of Paediatric Palliative Care. J Paediatr Child H. 2016;52:979–982.

4. Ahmann E, Abraham M, Johnson B. Institute for patient- and family-centered care. Emergen Med. 2010;15:109–111.

5. Luckett T, Phillips J, Agar M, Virdun C, Green A, Davidson PM. Elements of effective palliative care models: a rapid review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:136.

6. Limbo R, Wool C. Perinatal palliative care. J Obstetric Gynecol Neonat Nurs. 2016;45:611–613.

7. Ajayi TA, Edmonds KP. Palliative care answers the challenges of transitioning serious illness of childhood to adult medicine. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:469–471.

8. Selman LE, Brighton LJ, Robinson V, et al. Primary care physicians’ educational needs and learning preferences in end of life care: a focus group study in the UK. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16:17.

9. Reid FC. Lived experiences of adult community nurses delivering palliative care to children and young people in rural areas. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2013;19:541–547.

10. Herbert A, Bradford N, Donovan L, Pedersen L, Irving H. Development of a state-wide pediatric palliative care service in Australia: referral and outcomes over two years. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:288–295.

11. Baggio S, Herbert A, Delaney A, et al. A national quality of care collaboration to improve Paediatric Palliative Care outcomes.

12. Mherekumombe MF. From inpatient to clinic to home to hospice and back: using the “Pop up” pediatric palliative model of care. Children. 2018;5(5):55.

13. Slater PJ, Herbert AR, Baggio SJ, et al. Evaluating the impact of national education in pediatric palliative care: the quality of care collaborative Australia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:927–941.

14. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357.

15. Wilcock PM, Stewart Brown GC, Bateson J, Carver J, Machin S. Using patient stories to inspire quality improvement within the NHS modernization agency collaborative programmes. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:422–430.

16. Bridges J, Gray W, Box G, Machin S. Discovery interviews: a mechanism for user involvement. Int J Older People Nurs. 2008;3:206–210.

17. NHS I. Learning from Patient and Carer Experience. A Guide to Using Discovery Interviews to Improve Care. Leicester, UK: NHS Modernisation Agency; 2009.

18. Slater PJ, Philpot SP. Telling the story of childhood cancer: an evaluation of the discovery interview methodology conducted within the Queensland Children’s Cancer Centre. Patient Intell. 2016;2016:39–46.

19. Cruickshank M, Wainohu D, Stevens H, Winskill R, Paliadelis P. Implementing family-centred care: an exploration of the beliefs and practices of paediatric nurses. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2005;23:31–36.

20. Dedoose. Dedoose Version 8.0.35, Web Application for Managing, Analyzing, and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data. Los Angeles, CA: LLC; 2018.

21. Braun V, Clarke V, Terry G. Thematic analysis. Qual Res Clin Health Psychol. 2014;24:95–114.

22. CareSearch. South Australia.

23. Levine S, O’Mahony S, Baron A, et al. Training the workforce: description of a longitudinal interdisciplinary education and mentoring program in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;53:728–737.

24. Downing K, Michelson K, Murday P, Arsala EG. Providing pediatric palliative care in Non-Urban Areas of Illinois: challenges identified and recommendations for process improvement (TH320D). J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;55:571.

25. James K, Schank C, Downing KK, et al. Pediatric palliative physician and nurse mentorship training program: a personalized didactic and experiential training curriculum developed to enhance access to care in non-metropolitan communities. Pediatr. 2018;142(1):Meeting Abstract, 656. Section on Hospice and Palliative Medicine Program.

26. Hinderer KA, Jarosinski JM, Seldomridge LA, Reid TP. From expert clinician to nurse educator: outcomes of a faculty academy initiative. Nurs Educ. 2016;41:194–198.

27. Fraser SE, Roth S, Vogt K, Clauson MI. Experience of Educators Who Have Participated in the Educator Pathway Program: a Qualitative Descriptive Study. Vancouver: Faculty Research and Publications, The University of British Columbia; 2016.

28. Schoening AM. From bedside to classroom: the nurse educator transition model. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2013;34:167–172.

29. Vesel T, Beveridge C. From fear to confidence: changing providers’ attitudes about pediatric palliative and hospice care. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;56(2):205–212.

30. Wiener L, Weaver MS, Bell CJ, Sansom-Daly UM. Threading the cloak: palliative care education for care providers of adolescents and young adults with cancer. Clin Oncol Adolesc Young Adults. 2015;5:1–18.

31. Widger K, Wolfe J, Friedrichsdorf S, et al. National impact of the EPEC-pediatrics enhanced train-the-trainer model for delivering education on pediatric palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(9):1249–1256.

32. Maddocks I, Rayner R. Issues in palliative care for indigenous communities. 2003;179(6):S17.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.