Back to Journals » Journal of Pain Research » Volume 9

Performance, pain, and quality of life on use of central venous catheter for management of pericardial effusions in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery

Authors Ghods K, Razavi MR, Forozeshfard M

Received 5 July 2016

Accepted for publication 13 September 2016

Published 31 October 2016 Volume 2016:9 Pages 887—892

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S116483

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 6

Editor who approved publication: Dr Michael Schatman

Kamran Ghods,1 Mohammad Reza Razavi,2 Mohammad Forozeshfard3

1Clinical Research Development Unit (CRDU), Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Kowsar Hospital, 2Nursing Care Research Center, 3Cancer Research Center, Department of Anesthesiology, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran

Abstract: Different pericardial catheters have been suggested as an effective alternative method for drainage of pericardial effusion. The aim of this study was to determine the performance, pain, and quality of life on use of central venous catheter (CVC) for drainage of pericardial effusion in patients undergoing open heart surgery. Fifty-five patients who had developed pericardial effusion after an open heart surgery (2012–2015) were prospectively assessed. Triple-lumen central catheters were inserted under echocardiographic guidance. Clinical, procedural, complication, and outcome details were analyzed. Intensity of pain and quality of life of patients were assessed using the numerical rating scale and Short-Form Health Survey. CVC was inserted for 36 males and 19 females, all of whom had a mean age of 58.5±15 years, and the mean duration of the open heart surgery was 8±3.5 hours. The mean central venous pressure catheter life span was 14.6 days. No cases of recurrent effusion and complication were reported. The technical success rate of procedure was 100%. Intensity of pain and quality of life of patients had improved during follow-up. CVC insertion is a safe and effective technique for the management of pericardial effusion in patients after open heart surgery.

Keywords: coronary artery bypass graft, pericardial effusion, central venous catheter

Introduction

Pericardial effusion is a common finding after an open heart surgery and is an early complication that occurs after bleeding and the accumulation of blood in the pericardial cavity.1–4 The effective control of pericardial effusion depends on the presence or likelihood of cardiac tamponade, causing compromised hemodynamic symptoms and changes.5 Patients without cardiac tamponade experience fever, chest pain, and pericardial friction rub as well as mild effusion (<10 mm) and moderate effusion (10–20 mm) in some cases.4,6 These patients are often treated with anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs alongside colchicine.7 Emergency treatment is required in the case of severe pericardial effusion (>20 mm) presenting with cardiac tamponade.4 Pericardiocentesis is the first-line treatment for this condition as it is the least damaging and least invasive option.8 Simple pericardiocentesis is the chosen method of therapy when the recurrence of effusion is absolutely unlikely; however, since 40%–50% of patients have recurrent effusion, the pericardial window technique is used to drain the effusion.9,10 The pericardial window technique consists of an open thoracotomy or a video-assisted thoracic surgery and requires a chest tube to be inserted and an incision to be made in the pericardium through one of two methods: subxiphoid pericardial window or transdiaphragmatic pericardial window.11 This technique is used nowadays for detecting damage to the heart after a trauma and is only recommended in the case of pericardial thrombus as it is an invasive technique with the risk of secondary infection that also requires continuous monitoring.12

Echocardiographic guidance for the insertion of a pericardial catheter is an alternative method of effusion drainage.13 Different pericardial catheters have been made and used so far for ensuring that patients experience the least amount of pain and limitations without having the efficiency of the technique compromised. Palacios et al14 first used balloon pericardiotomy as an alternative to surgery for draining pericardial effusion via the subxiphoid approach, in which other researchers then examined and confirmed its use along with the use of double-balloon pericardiotomy.15,14 The technique is especially helpful for patients with malignancies and drains up to 97% of the accumulated fluid, prevents the recurrence of effusion in >80% of the cases, and leads to complications in only 4.7%; however, it is often a painful procedure due to the release of pericardial tension and therefore requires analgesics.2,16,17 Other complications reported include fever, pneumothorax, a necessary chest tube insertion (in 20% of the cases), and pericardial bleeding.2,16,17

Given the special use of balloon pericardiotomy in patients with cancer, the complications it entails, and its unsupported use in the drainage of pericardial effusion after an open heart surgery, the present study examines the performance, pain, and quality of life in drainage of pericardial effusion through the insertion of central venous catheter (CVC) in the pericardial cavity under echocardiographic guidance via a subxiphoid approach.

Materials and methods

Patients

In this prospective study, we selected 55 patients who had developed pericardial effusion after an open heart surgery between May 2012 and September 2015. All the patients underwent an open heart surgery in the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery of Kowsar Hospital in Semnan, Iran. The total number of patients who underwent cardiac surgery in this hospital during the same time period was 613 cases, and there was no postoperative mortality due to untreated cardiac tamponade due to pericardial effusion. The patients’ postsurgical pericardial effusion was symptomatic and was diagnosed using chest X-ray (CXR) and lung CT scan; moreover, the patients did not respond to regular treatments and were therefore candidates for surgical drainage. The patients whose clinical status was such that they could not respond to the questions were excluded from the study. Given that the patients had an acute condition, no international normalized ratio and platelet count limitations were set for them. Ethical approval was obtained for this study from the Ethics Commitee of the Semnan University of Medical Sciences. All the participants submitted written informed consent for this study, based on the Declaration of Helsinki.

Central venous catheter

Triple-lumen central catheters, a type of nontunneled central catheter, were used. These types of catheter are very common for enabling a temporary access to the central circulation and have different lengths, from 15 to 30 cm, and are made of different materials, such as polyurethane, silicone, and so on. A 7.5–8.5 French triple-lumen catheter (Multi-Lumen Indwelling Catheter: 7.5–8.5 Fr ×20 cm, AK-45703-BX, Radiopaque Polyurethane with Blue FlexTip®; Arrow Medical, Cleveland, OH, USA) was used in this study.

Procedure

The patients were first briefed on the surgical procedure about to be performed on them and were then transferred to the operating theater for pericardial effusion drainage. Precautionary measures for prevention of infection were carried out just as in any other surgical procedure. The patients were placed in the supine position with their hands at their sides. The skin and the subcutaneous tissue of the left xiphocostal area were then anesthetized with 2% lidocaine. To prevent trauma and damage to the heart and to ensure the maximum amount of aspirated fluid in patients with pericardial effusion, under transthoracic echocardiographic guidance (using a probe) a 12-gauge needle was inserted first; a guidewire was then passed through the needle, and the needle was finally removed. A dilator was inserted over the guidewire, and a central venous pressure catheter (12–14 Fr) using a three- or four-way valve was then inserted into the pericardial cavity after the dilator was removed. The catheter was then fixed to the skin and its end connected to a sterile bag using a 2 cc piston syringe (Figure 1). A 4-0 silk suture was then used to secure the catheter to the skin, and a sterile transparent dressing was applied every 12 hours to prevent infections. Patients were also trained on its proper care as well as on measuring the effusion on a daily basis. They were instructed to drain the effusion to prevent pericardial adhesion and fluid accumulation in excess of 30 mL per day. The catheter remained in place for as long as the effusion drainage exceeded 25 mL per day. Outpatients who had no hemodynamic problems were discharged 12 hours after catheter insertion on the doctor’s recommendation. They were asked to visit the hospital for catheter removal if their daily drainage reached <25 mL. In the case of hospitalized patients, drainage control was performed by the researcher. Before removing the catheter at the doctor’s discretion, weekly echocardiography and CXR were performed to ensure the complete drainage of the effusion and proper catheter insertion. All the necessary training was provided to the patients and daily telephone follow-ups were carried out with the patients.

| Figure 1 Central venous catheter insertion for pericardial effusion drainage via a subxiphoid approach. |

Data collection

Before performing the surgical procedure, the patients’ demographic data, including age, gender, and the time of open heart surgery, were collected through their medical records and from the patients themselves or their relatives. After the surgery, the amount of daily drainage of pericardial fluid, the duration of catheter insertion, infection, complications, the amount of pain 6 and 12 hours after catheter insertion, and quality of life were measured every week after catheter insertion and before its removal.

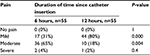

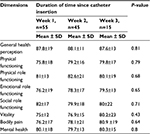

The intensity of pain was assessed using a numerical rating scale from 0 to 10. Each patient rated their pain as either zero (indicating no pain), 2–4 (indicating mild pain), 4–6 (indicating moderate pain), or 7–10 (indicating severe pain). The patients were also evaluated for the amount of analgesics taken during their hospital stay (as per the medical records) or at home (through asking the patient in each hospital visit). The patients’ quality of life was assessed using the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). This 36-item questionnaire evaluates the quality of life in eight dimensions, including general health perceptions (six items), physical functioning (ten items), physical role functioning (four items), emotional role functioning (two items), social role functioning (two items), vitality (four items), bodily pain (two items), and mental health (five items). Several studies have confirmed the validity and reliability of this questionnaire. The scores obtained in each dimension range from 0 (the worst) to 100 (the best). The present study also examined the validity of this questionnaire using similar studies and expert views and confirmed its reliability with a Cronbach’s α of 0.78 on a sample of 20 patients.

Statistical analysis

Data obtained were analyzed using SPSS version 22 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The paired t-test and analysis of variance were used to compare the normally distributed data, whereas the Wilcoxon’s paired test and the Kruskal–Wallis test were used to compare the nonnormally distributed data. The level of statistical significance was set at P-value <0.05.

Results

The study was conducted on 55 patients, 36 males (65%) and 19 females (35%). The mean age of the patients was 58.5±15 years. The time from surgery to presentation with the pericardial effusion was 7.4 days, and the mean duration of the open heart surgery was 8±3.5 hours. In all patients, the type of open heart surgery performed was coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) only. An echocardiography and a CXR showed that the CVC insertion was successful in all the cases, and no instances of catheter displacement in the pericardial cavity or catheter migration were reported, making catheter replacement or the surgical insertion of chest tube unnecessary. A minimum drainage of 30 mL per day was observed in all the cases, which was taken as a criterion for proper catheter functioning. The minimum drainage measured was 95 mL per day and the maximum 335 mL per day. The mean central venous pressure catheter life span was 14.6 days, ranging from a minimum of 7 days and a maximum of 21 days. The catheter was removed after 7–12 days in 18 patients (32.7%), after 13–18 days in 30 patients (54.5%), and after 19–21 days in seven patients (12.8%). No cases of recurrent effusion were reported as the catheter was not removed for as long as the drainage was >25 mL.

No complications or infections were reported after the catheter was inserted and during its life span. The intensity of pain was moderate in the first 6 hours after catheter insertion in 65% of the patients and mild in the 12 hours after catheter insertion in 80%.

The statistical analysis showed that the number of patients who experienced moderate pain 12 hours after catheter insertion was significantly lower than the number of patients who experienced this intensity of pain in the first 6 hours after the insertion procedure (P<0.05), as the number of patients who experienced only mild pain increased by the hour.

Only eight patients requested to be given pain killers during the first 12 hours after their catheter insertion; two of them were administered 5 mg morphine and the other six were given acetaminophen and diclofenac suppository. In addition, 17 patients (31%) reported that they had taken oral analgesics including acetaminophen codeine, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen and diclofenac suppository at home. Table 1 presents the intensity of pain in the patients 6 and 12 hours after catheter insertion.

| Table 1 The intensity of pain according to the NRS using the number of patients Abbreviation: NRS, numerical rating scale. |

The SF-36 showed that the patients had a good quality of life. The analysis of variance showed that time makes a significant difference in the amount of pain experienced (P>0.05; Table 2).

| Table 2 Patients’ quality of life when living with a catheter Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation. |

Discussion

The present report is the first study on the use of CVC for the drainage of pericardial effusion. The risk of pericardial effusion recurrence following pericardiocentesis is reported to reach 90% and is known to increase mortality and morbidity rates, and it also incurs considerable financial costs.18 Considering the invasive nature of the pericardial window technique and the risk of infection associated with it, catheter insertion in the pericardial cavity is recommended to take place under echocardiographic guidance. The insertion of CVC in the pericardial cavity for pericardial effusion drainage proved successful in the present study, caused no complications or infections, and resulted in a minimum drainage of 30 mL per day; these advantages indicate the effectiveness of the technique. The life span of a catheter depends on the patients’ hemodynamic status and logical considerations, and its effectiveness was maintained for 3 weeks in 15 patients. In addition to maintaining its original effectiveness and lacking complications, the quality of life and insertion pain with which it is associated were acceptable, as the patients felt a gradual reduction in pain and adapted better to living with catheter with time. The advantages of using CVC should be compared with the advantages of using pericardial window and balloon pericardiotomy.

Pericardial window has a high rate of success and a low risk of recurrence and is therefore the recommended approach for pericardial effusion drainage. In this technique, a 26–28 F chest tube is inserted through pericardiotomy using a separate stab wound in the upper left abdomen, and postoperative suction drainage is thus performed. This method is more invasive than the CVC insertion technique and entails a greater risk of wounds. Moreover, since it requires cuts and incisions, and therefore the opening of the incisions, it is associated with a greater risk of infection and general anesthesia complications. The chest tube technique can also create limitations for the patient. The hospital mortality rate is reported as 10.7%, a 5-year survival rate is 51%, and the morbidity rate is 67% in patients undergoing pericardial window for the drainage of pericardial effusion.19,20 No mortalities or complications such as pneumothorax and infections were observed in this study. CVC insertion was performed in this study under echocardiographic guidance and without general anesthesia, therefore not necessitating the chest to be cut open.

Echocardiography-guided pericardiocentesis is a safe technique that enables different approaches to the drainage of effusion in addition to the subxiphoid approach.21 Moreover, the incision made through performing this technique is smaller compared to the incision made for pericardial window, which may explain the zero rates of mortality, morbidity, infection, and complications. Recent studies recommend the pericardial window for a quick diagnosis of cardiac injury, as several researchers have presented their own account of performing the pericardial window technique for diagnosing cardiac injury in patients with stable conditions.22–24 According to the majority of these studies, pericardial window is a standard technique, as it helps to detect or rule out cardiac injuries and is associated with the lowest morbidity rates, even if the gastrointestinal tract has been identified as a source of contamination.22

The percutaneous balloon technique has recently become more common for the drainage of fluids. This technique can be performed in various ways, but is not offered in most health care centers. Balloon pericardiotomy is apparently very helpful for patients who have malignant effusions and who are exposed to a great risk of recurrence – such patients require a definitive approach that can be carried out without surgery.25,26

In a retrospective study, Mangi et al27 used a pigtail-shaped drainage catheter for pericardiocentesis >7 days after cardiac surgery through a subxiphoid approach under electrocardiographic and fluoroscopic guidance. The success rate of drainage was 97%, and only one patient required pericardial window. Also, they showed that pericardiocentesis with catheter placement for patients with valve operation is highly effective, and they can be reanticoagulated after pericardiocentesis.27

Swanson et al16 employed the percutaneous balloon technique for primary malignant pericardial effusion and reported the procedure to have been successful in 96% of the patients; however, balloon pericardiotomy was associated with complications such as procedure-related pain in 7.4% of the patients. Wang et al17 examined the use of immediate and elective double-balloon pericardiotomy in patients with a large amount of malignancy-related pericardial effusion. The pigtail catheter was removed 2.9±0.8 days after the procedure in immediate double-balloon pericardiotomy and 4.0±3.5 days after in delayed double-balloon pericardiotomy. The drainage was successful in 92% of the patients undergoing immediate double-balloon pericardiotomy and 87% of those undergoing delayed double-balloon pericardiotomy. Pneumothorax was reported in 6% of the entire sample of patients and in 33% of the immediate and 26% of the delayed double-balloon pericardiotomy patients experienced fever.17 Wang et al17 considered successful drainage as one that posed no risks of pericardial effusion recurrence; in the present study, however, a successful drainage was defined by draining a minimum amount of 30 mL per day. In this study, drainage was successful in 100% of the patients, and no complications were reported in spite of leaving the CVC inserted for 3 weeks.

Balloon pericardiotomy is almost always associated with pain, given that the pericardium gets stretched through this procedure.28 The present study measured the intensity of pain using the numerical rating scale 6 and 12 hours after the insertion of the catheter. Only two patients reported their pain to be severe in the first 6 hours and one patient in the second 6 hours; however, the administration of 5 mg morphine relieved their pain. Moreover, six patients reported their pain to have alleviated 12 hours after the catheter insertion and 17 patients reported pain relief at home after discharge and with the use of oral analgesics such as acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and rectal diclofenac suppository without recourse to intravenous analgesic administration.

The patients’ quality of life was assessed with the catheter inserted and was deemed satisfactory, as it improved on a weekly basis, implying that the patients have learned to adapt to living with a catheter.

Other advantages of this technique include its low costs, ready availability, an earlier discharge from the hospital and the continuation of care at home, and the easy application of dressings and self-care for the catheter. In contrast, chest tube poses greater limitations for the patient.

A randomized clinical trial is recommended to be conducted on the efficiency and safety of CVC insertion versus the pericardial window technique and balloon pericardiotomy.

A potential advantage to this technique is cost-effectiveness, which was not evaluated in this study. Another study could be done to report the potential magnitude of cost savings using this technique versus conventional chest tubes or pigtails. All patients underwent CABG, and so the use of this technique in another type of open heart surgery such as valve operation was not reviewed. Also, the safety of CVC insertion in pericardial cavity should be determined in patients with high international normalized ratio due to warfarin therapy and other coagulation disorders.

Conclusion

CVC insertion under echocardiographic guidance is a safe and effective method for the drainage of pericardial effusion and can help all the patients with post-CABG pericardial effusion regardless of having received the immediate or delayed treatment.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the staff of Kosar Hospital under supervision of Semnan University of Medical Sciences for their cooperation.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Andreasen JJ, Sørensen GV, Abrahamsen ER, et al. Early chest tube removal following cardiac surgery is associated with pleural and/or pericardial effusions requiring invasive treatment. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49(1):288–292. | ||

Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, Trinchero R, Adler Y. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010;121(7):916–928. | ||

Levy PY, Corey R, Berger P, et al. Etiologic diagnosis of 204 pericardial effusions. Medicine. 2003;82:385–391. | ||

Imazio M, Adler Y. Management of pericardial effusion. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(16):1186–1197. | ||

Sagristà-Sauleda J, Mercé AS, Soler-Soler J. Diagnosis and management of pericardial effusion. World J Cardiol. 2011;3(5):135–143. | ||

Asteggiano R, Bueno H, Caforio AL, Carerj S, Ceconi C. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases–Web Addenda. Eur Heart J. 2015. | ||

Meurin P, Lelay-Kubas S, Pierre B, et al. Colchicine for postoperative pericardial effusion: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Heart. 2015;101:1711–1716. | ||

Halabi M, Faranesh AZ, Schenke WH, et al. Real-time cardiovascular magnetic resonance subxiphoid pericardial access and pericardiocentesis using off-the-shelf devices in swine. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:61. | ||

Tsang TS, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Bailey KR, Seward JB. Outcomes of clinically significant idiopathic pericardial effusion requiring intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:704–707. | ||

Imazio M. Surgery for pericardial diseases. Myopericardial Diseases. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2016:63–67. | ||

Van Schil P, Paelinck B, Hendriks J, Lauwers P. Pericardial window. In: Astoul P, Tassi GF, Tschopp JM, editors. Thoracoscopy for Pulmonologists. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2014:197–204. | ||

Hommes M, Nicol A, van der Stok J, Kodde I, Navsaria P. Subxiphoid pericardial window to exclude occult cardiac injury after penetrating thoracoabdominal trauma. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1454–1458. | ||

Kim EY, Won JH, Kim J, Park JS. Percutaneous pericardial effusion drainage under ultrasonographic and fluoroscopic guidance for symptomatic pericardial effusion: a single-center experience in 93 consecutive patients. J Vas Interv Radiol. 2015;26(10):1533–1538. | ||

Palacios IF, Tuzcu EM, Ziskind AA, Younger J, Block PC. Percutaneous balloon pericardial window for patients with malignant pericardial effusion and tamponade. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1991;22(4):244–249. | ||

Sawant R, Rajamanickam A, Kini AS. Pericardiocentesis and Balloon Pericardiotomy. Practical Manual of Interventional Cardiology: Springer; 2014:293–297. | ||

Swanson N, Mirza I, Wijesinghe N, Devlin G. Primary percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy for malignant pericardial effusion. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;71(4):504–507. | ||

Wang HJ, Hsu KL, Chiang FT, Tseng CD, Tseng YZ, Liau CS. Technical and prognostic outcomes of double-balloon pericardiotomy for large malignancy-related pericardial effusions. chest. 2002;122:893–899. | ||

Bhardwaj R, Gharib W, Gharib W, Warden B, Jain A. Evaluation of safety and feasibility of percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy in hemodynamically significant pericardial effusion (Review of 10‐Years Experience in Single Center). J Interv Cardiol. 2015;28:409–414. | ||

Park JS, Rentschler R, Wilbur D. Surgical management of pericardial effusion in patients with malignancies. Comparison of subxiphoid window versus pericardiectomy. Cancer. 1991;67:76–80. | ||

McDonald JM, Meyers BF, Guthrie TJ, Battafarano RJ, Cooper JD, Patterson GA. Comparison of open subxiphoid pericardial drainage with percutaneous catheter drainage for symptomatic pericardial effusion. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:811–816. | ||

Maggiolini S, Gentile G, Farina A, et al. Safety, efficacy, and complications of pericardiocentesis by real-time echo-monitored procedure. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:1369–1374. | ||

Fraga GP, Espínola JP, Mantovani M. Pericardial window used in the diagnosis of cardiac injury. Acta Cir Bras. 2008;23:208–215. | ||

Efron DT. Subxiphoid pericardial window to exclude occult cardiac injury after penetrating thoracoabdominal trauma (Br J Surg 2013; 100: 1454–1458). Br J Surg. 2013;100(11):1458. | ||

Alhadhrami B, Alzahrani M. Sternotomy or drainage for a hemopericardium after penetrating trauma: a safe procedure? Ann Surg. 2016;263:e32. | ||

Ruiz-García J, Jiménez-Valero S, Moreno R, et al. Percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy as the initial and definitive treatment for malignant pericardial effusion. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2013;66:357–363. | ||

Jones DA, Jain AK. Percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy for recurrent malignant pericardial effusion. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(12):2138–2139. | ||

Mangi AA, Palacios IF, Torchiana DF. Catheter pericardiocentesis for delayed tamponade after cardiac valve operation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:1479–1483. | ||

Jneid H, Maree AO, Palacios IF. Acute pericardial disease: pericardiocentesis and percutaneous pericardiotomy. In: Mebazaa A, Gheorghiade M, Zannad FM, Parrillo JE, editors. Acute Heart Failure. London, UK: Springer; 2008:255–265. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.