Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 7

Perceptions of final-year medical students towards the impact of gender on their training and future practice

Authors Van Wyk J, Naidoo S, Moodley K, Higgins-Opitz S

Received 27 February 2016

Accepted for publication 10 April 2016

Published 23 September 2016 Volume 2016:7 Pages 541—550

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S107304

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Jacqueline M Van Wyk,1 Soornarain S Naidoo,2 Kogie Moodley,1 Susan B Higgins-Opitz3

1Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine, University of KwaZulu‑Natal, 2Faculty of Health Sciences, Durban University of Technology, 3School of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu‑Natal, Durban, South Africa

Introduction: Following policy implementations to redress previous racial and gender discrepancies, this study explored how gender impacted on the clinical experiences of final-year medical students during their undergraduate training. It also gathered their perceptions and expectations for the future.

Methods: This cross-sectional, mixed-method study used a purposive sampling method to collect data from the participants (n=94). Each respondent was interviewed by two members of the research team. The quantitative data were entered into Excel and analyzed descriptively. The qualitative data were transcribed and thematically analyzed.

Results: The majority of the respondents still perceived clinical practice as male dominated. All respondents agreed that females faced more obstacles in clinical practice than males. This included resistance from some patients, poor mentoring in some disciplines, and less support from hostile nurses. They feared for their personal safety and experienced gender-based stereotyping regarding their competency. Males thought that feminization of the profession may limit their residency choices, and they reported obstacles when conducting intimate examinations and consultations on female patients. Both males and females expressed desire for more normalized work hours to maintain personal relationships.

Conclusion: Social redress policies have done much to increase equal access for females to medical schools. Cultural values and attitudes from mentors, peers, and patients still impact on the quality of their clinical experiences and therefore also their decisions regarding future clinical practice. More mentoring and education may help to address some of the perceived obstacles.

Keywords: South Africa, opportunities, challenges, stigma, racial stereotypes, students

A Letter to the Editor has been received and published for this article

Introduction

There are biological and gender differences inherent to all human beings which impact on their experiences and health. For example, 99% of the recorded five-hundred thousand maternal deaths occur in developing countries; that is, females in developing countries are 25 times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes.1 The health and well-being of females is an area of great concern mainly because they are seen to be disadvantaged by deeply rooted sociocultural factors and practices.2

The impact of feminization in the medical profession is not well understood globally.3 Concern especially in developed countries has highlighted the possible lack of care to male patients in disciplines such as urology and surgery where a preference for doctors of the same gender and ethnicity had been observed.4 Research suggests that care rendered by female physicians to female patients may be more effective than care provided by male physicians.5 Questions have also been raised about the quality of care and the adaptability of the health care system if females predominate in the medical workforce.6

Kilminster et al believe that feminization and its impact are still not well understood.3 If this is so, then even less is known about this phenomenon in low- to middle-income countries. It is generally known that health care in South Africa is delivered inequitably in terms of both access to health care and its outcomes. In this context and on a global scale, females have been identified as the biggest consumers of health care services. Not only are they more likely to access health services and be hospitalized but also will they endure the differentiated outcomes inherent in the system.7

The South African health sector has a critical shortage of skilled human resources.8 This is particularly evident in the public sector and in rural areas. Attempts have been made at national and local levels to address this shortage.8,9 At an institutional level, medical schools in South Africa have responded by increasing the intake of students, shortening curricula, and/or increasing the duration of clinical rotations and internship periods.9 The resultant effect at most medical faculties is visible in the form of the increased ethnic student diversity and a greater female presence in student cohorts.9 For example, the female admissions between 1999 and 2011 at the eight national medical training facilities increased to ~55%.9 The current workforce comprises individuals, each with their career aspirations, areas of specialty, and decisions on how best to serve in the health care system. It is thus important to recognize that their experiences during training and perceptions of the practice environment would impact on their future decisions. The quadruple burden of diseases in South Africa, that is, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, noncommunicable disease, and trauma due to violence, places increasing demands on the health care system.10 It is therefore imperative to gain an understanding of how students perceive the current South African clinical practice environment, the obstacles and advantages that they encounter now, and how they anticipate their future in clinical medical practice in South Africa.

The design of this study was informed and drew on social dominance theory11 and how different groups interact and relate in racial and cultural settings. This explains the existence of group-based social hierarchy, especially how it is formed and maintained in societal structures and institutions as representations of society. Gender and gender dominance, as the most common stereotypes across most cultures, have been maintained because the biological role of males has been presented as breadwinners and protectors, while that of females as nurturers, homemakers, and carers.11 The theory also explains how power, wealth, health, status, responsibility, and political influence in the form of positive social value are freely distributed to the “elite”, while negative social value is disproportionately left or forced upon subordinate groups. These could take the forms of substandard housing, disease, underemployment, dangerous and distasteful work, disproportionate punishment, stigmatization, and vilification.11 Social dominance theory assumes that we must understand the processes producing and maintaining prejudice and discrimination at multiple levels, including cultural ideologies and policies, institutional practices, relations of individuals to others inside and outside their groups, the psychological predispositions of individuals, and the interaction between the evolved psychologies of men and women.11

Gender inequity is a global phenomenon, and historical disparities have also impacted on delivery of care at the local level in South Africa. Male domination has also been incorporated into all social structures and work systems, and it is likely that male and female final-year students may have a differentiated and gendered experience of their clinical training in local hospital wards. It is also necessary for future health care planning so that curriculum designers become aware of how male and female students perceive and experience South African clinical practice and the obstacles faced by final-year students in the daily practice thereof. This study was conducted in the context of the critical shortage of clinicians to serve in the poverty-stricken and resource-constraint South African context where an increasing trend to accept more female students into the medical profession had been noticed. The study explored how final-year medical students perceived their future in a clinical environment in South Africa, particularly anticipated obstacles and the impact of feminization.

Methods

This cross-sectional, mixed-method study was conducted with final-year medical students (N=201) from the Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine of the University of KwaZulu-Natal. This purposive sample comprised senior medical students who had already been exposed to various clinical rotations in a 5-year problem-based learning curriculum. Admission at the school where the study was conducted follows a quota that mirrors a racial distribution similar to that of the province. The quota allows for the enrollment of 70% Black, 19% Indian, 9% Colored, and 2% White students. A tendency over the last 10 years also favored a 60% representation of females. The students in the sample (n=94) who had been selected for their experience in and exposures to the clinical setting were all interviewed individually. The sample reflected the student population at the school in terms of racial, cultural, and religious diversity. The reason for conducting a cross-sectional study was to obtain a snapshot of students’ experience 15 years after election of a democratic government and implementation of a new constitution. Furthermore, students on the program had had extensive exposure to the clinical environment since their third year of study. All the students were invited to participate. The purpose of the study was explained prior to the students’ participation. Written informed consent was obtained prior to the interview, and anonymity and confidentiality were assured.

Using a semistructured interview schedule, a two-member team conducted the interviews. One member interviewed the participant, while the second member took field notes and audio-recorded the session. Each interview lasted ~30–45 minutes. The questions explored demographic information, perceptions of the clinical practice environment, and challenges relating to gender and strategies used to overcome these. The biographical data and field notes were captured on MS-Excel XP (version), and the recorded data from interviews were transcribed and checked by members of the team before coding and analysis. Institutional ethical approval was obtained (University of KwaZulu-Natal HSS/0404/07).

Results

Demographic data

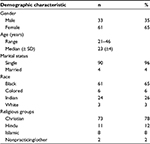

The biographical characteristics of the cohort are summarized in Table 1. Ninety-four final-year students (48%) were interviewed. The majority of the participants were Black (65%), females (65%), single (96%), and Christians (78%). The average age of participants was 23±4 years.

| Table 1 Demographic profile of participants (N=94) Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation. |

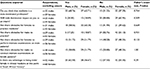

The perceptions of the respondents were analyzed as themes and in response to the questions posed during the interview. The questions and the semiquantitative aspects of their responses are presented in Table 2, while the themes and subthemes extracted from the students’ comments are shown in Table 3. The qualitative themes are presented as part of the “Discussion” section to ensure logical flow, brevity, and clarity of the research report.

| Table 2 Participant’s perceptions of the impact of gender on their clinical practice |

| Table 3 Themes and subthemes emanating from participants’ comments Abbreviations: A, African; C, Colored; I, Indian; W, White; F, female; M, male; A–F, clinical group rotation + number. |

Discussion

The demographic representation of the sample reflected the student cohort, although fewer students were present in the Black and Colored groups. The lower representivity in these groups was likely due to attrition which generally affects more students from previous disadvantaged Black and Colored backgrounds. The percentage of females in the sample was however higher (65%) than that of the cohort (60%). There was nevertheless a marked difference between the number of females recorded in the first graduating medical class of 1957 when four females (33%) graduated as part of the first medical cohort of 12 final-year students.12

From the quantitative data presented in Table 3, it is evident that >60% of the male and female students perceived clinical practice in South Africa as male dominated. The majority (67% males and 62% females) thought that this perceived male domination would not impact on them. All respondents (55% males and 53% females) thought that females faced more obstacles in clinical practice than males.

Forty-five percent of the males and 50% of the females thought that females experienced and should anticipate more obstacles when conducting intimate examinations on patients of opposite sex. Almost similar percentages (47% males and 49% females) perceived that males also faced obstacles in performing intimate examinations on female patients. However, 61% of the males perceived their gender as an advantage, and 52% of the female respondents indicated that they perceived being female as a disadvantage in the current and near-future South African clinical practice setting. The views expressed by the respondents (qualitative data) are discussed according to the themes as shown in Table 3.

Impact of feminization on students

Only a few (<20%) of the male students thought that the increased intake of female students may impact on them during their internship. They expressed concern that the increased female presence might affect their chances of being accepted into specialty training of their first and preferred choice. They anticipated that some specialties may be guided by equity and affirmative action rules to reserve places for females from previously disadvantaged racial and ethnic groups especially in disciplines which were previously considered to be “male strongholds”. Most female students responded with optimism to the increased presence of females at the undergraduate level. They anticipated that the increased female presence would not impact on them but that it would translate into an increased presence of female role models and mentors in the future which could impact on the female workload and duty schedules. They also anticipated that a greater female presence would offer more flexible work hours and policies which should allow more time to invest in personal relationships with friends and family (Tables 2 and 3).

General obstacles to practice medicine

The majority of the respondents agreed that female students encountered and should anticipate more obstacles in their daily clinical practice as indicated by the spread of the subthemes in Table 3. Obstacles for females ranged from subversive practices such as dealing with patients especially older males from cultural groups other than their own which often resisted openly. They also anticipated obstacles related to stigma associated with being labeled as an “incompetent female” in their dealings with some patients, and they observed and mentioned the differentiated experiences and relations with nurses and support staff. One such issue relating to patients’ beliefs is illustrated as follows.

I think …the problem is the mentality of the patient. They don’t regard females as good enough doctors and so it’s still…, if that can be sorted ..., the mind-set of patients that needs to change. [AF-19]

Male-dominated clinical training environment

Females in our study anticipated having to work harder to be accepted in some disciplines. For female students, the perception of having to work in a male-dominated environment impacted on their confidence to practice especially in disciplines such as urology and surgery where they observed and experienced the presence of fewer female role models (Table 3). Female students in this study also expressed concern about being accepted in disciplines which are seemingly intolerant to their presence. They thought that they lacked practice in their interactions with sufficient male patients. They perceived that the lack of female role models in these disciplines impacted on the quality of their training, supervision, and mentoring.

The performance of young people in national examinations has finally buried the notion that females are intellectually less able than males.12,13 In fact, even at the Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine, females have started to outperform males in most academic years on the undergraduate program.14 In addition, a vicious cycle seems to exist where female students’ perceptions of incompetence in clinical practice are directly related to them having had fewer opportunities to perform and complete specific procedures when compared to their male counterparts15 which then impact on their confidence to perform specific skills.

Research in the Norwegian context suggested that females, especially when placed in highly competitive environments, will have an improved and increased clinical experience if they (female students) insist on their right to learn new operations and procedures.16 The extent to which female students will encounter praise or criticism for such an initiative in the current gendered and cultural setting in South Africa warrants further exploration and did not fall within the scope of the present study. The absence of a critical number of female mentors therefore may deter females from entering a specialization where they perceive some sort of negative gender stereotyping or a hostile training environment which they perceive as limiting their potential and self-efficacy.

Work environment and collegiality

Although some females anticipated greater access to male-dominated specialties, others were cautious of subversive practices and policies such as “poor support for those with family commitments, irregular work hours, and requirements of supernatural strength to succeed in some specialties”, which may hinder collegial work in disciplines viewed as less receptive to females. The female students’ concerns seem valid as evidence suggests that mentors and role models play a critical role in training as it also impacts on decisions of female faculty regarding specialty choices.17,18

This finding confirms those of previous studies that indicated that females tend to avoid specialties where they perceive an absence of role models.17,18 Research has also indicated that the hierarchical structure of academic medicine reduces transparency in decision making and impedes the advancement of females.19 Students in this study were also aware of the eminent choices that awaited them between having a family and a career. These fears are not unfounded as a study reported the negative impact of parenthood on the career of the female physician.20 These authors also reported females with children as receiving less mentoring, and having had less career success and career support than their male counterparts.20 This implies the need for leaders and heads of specialties to make conscious decisions about strategies and mechanisms to create supportive environments to ensure the sustainability of both the service and the specialization.

Work–lifestyle balance

The female students in our study had similar perceptions as those expressed in a study where female doctors believed that they have to work harder, are afforded a lesser status, and generally find it more difficult to get accepted into general practitioner partnerships.21 A number of studies have reported on the career choices of students and interns and how their quest for a controllable lifestyle impacts on their career choices.22,23 In this regard, reports indicate that females feel limited when they are expected by societal norms to carry the responsibility of their families and house work22 and often find it impossible to reconcile being discriminated against at work and the demands of having a home and maintaining relationships with their loved ones.24

While some females mentioned the option of not getting married, the majority of male and female students in our cohort however expressed some hope to achieve an improved work–life balance. The findings of this study support those of others that indicated that the increasing trend to match their choice of specialty to accommodate a better work–lifestyle balance is not a phenomenon unique to females.23,25,26

Obstacles: intimate examinations

As indicated in Table 2, both females and males were unable to decide as to whether obstacles existed for students to conduct intimate examination on patients of the opposite sex. However, qualitatively, students did cite patient interaction and participation as critical to successful examination (Table 3).

They indicated that the degree to which patients refuse to be treated by female doctors varied according to the patients’ socioeconomic status, age, and cultural orientation. They also thought that patients’ attitudes toward being treated by female doctors depended on whether the consultation occurred in a public or at a private health care facility. Male students perceived that age, rather than their gender, played a more substantial role in patients’ decisions to be treated by them. The findings from this study seem to concur with studies suggesting that females gain more experience in dealing with conditions that specifically draw on their female skills.13

Personal safety and sexual harassment

The fear of sexual harassment remains a real concern for both female and male students. During intimate examinations on female patients, some males expressed fear in their interactions with the “obnoxious female patient” who was out to get the young male doctor “into trouble”. Female students mentioned that male patients sometimes provided unnecessary and explicit sexual histories and made inappropriate sexual remarks during consultations, especially if the consultation occurred in the absence of a male chaperone.

Female students additionally mentioned having to be watchful of their male counterparts to avoid being “taken advantage of” when interacting in multigendered teams. These findings are similar to those of a study by Ortiz-Hernandez et al who confirmed that sexual harassment remains a real concern for female students.27 The respondents of that study reported how females who seemingly disobeyed gender and cultural stereotypes suffered inappropriate behavior ranging from inappropriate staring to verbal and physical harassment. The reluctance of females to enter disciplines such as urology can also be understood when confronted with findings of a study that female residents are constantly confronted with negative behaviors from male patients and their male colleagues in the clinical context.28 This finding resonates in the current South African setting where sexual violence against females in general and female health care workers has escalated requiring interventions such as police escorts when paramedics respond to calls in townships and the need for self-defense training.29 The fact that many females experience unwanted sexual attention both in academic clinical training and work settings has been reported before.30–32

Attitudes of nurses

Some female students in this study reported having to down play their intelligence so that the nurse might not feel intimidated and “feel sorry and share her experiences”. There was also mention of the patients and members from the wider society who instinctively address a female student as “Nurse” and a male student as “Doctor”. Moreover, there are complex cultural differences between older generations and younger females which may complicate the quality of the interaction. Studies have reported female doctors as receiving less assistance and help from nursing staff than the support given to male physicians and that nurses tended to question the orders of female doctors more readily.33,34

Other studies have also indicated how the interactions between nurses and female doctors could be (re)producing traditional attitudes concerning the role of females in medical culture. In these cases, nurses were less respectful and confident in female doctors’ abilities and offered less help and expected female doctors to tidy up after themselves.35,36 Female doctors in the US also reported that they monitored their communication more carefully to avoid appearing either too demanding or not friendly enough and that they became accustomed to justifying their actions more than their male counterparts.37 In the current setting, some of the female students expressed concern about being perceived as obstructive by the nurses when they as “Black” students are not competent in communicating in isiZulu with the patients.

Advantage due to gender

There was a distinct difference in the responses of the male and female students to this question. A greater proportion (61%) of male students felt that it was still advantageous to practice as a male in South Africa. The reasons given for these perceptions included both patient and societal expectations of the typical doctor as being “male”. This contrasted well with the responses of female students (52%) who did not perceive a clear advantage to practice as a female doctor in the current setting.

Students perceived that their gender will impose either access or restrictions during their interactions with patients. Those female students who perceive some advantage (46%) to being female attributed the advantage to them having a better rapport with their patients. These findings are comparable to those of a study where more than half of the females thought that being caring, gentle, understanding, and sympathetic was an advantage in their practice of medicine.21 A study in the US similarly reported that the quality of the patient–doctor interaction was better if the attending doctor was a female.37 In that study, the authors reported that patients disclosed more biomedical and psychosocial information, made more positive statements, were more assertive, and interrupted female doctors more. Patients of female doctors were also less irritated or anxious than patients of male doctors.37 These perceptions of students in our study may need to be explored more in the future and in the current context. Females in our study additionally perceived that the greater presence of females in the profession will relate to an increased scope for specialization, and they hoped for more normalized work hours to accommodate more quality and family time.

Why the presence of females in health care still matters in South Africa?

Gender differences in South Africa have formed the basis of social stratification and gender imbalances that have persisted in most patriarchal societies. While South African legislation has been progressive in narrowing the gap to allow females more formal access to power and representation, students’ experiences in our study still reflected perceptions of gender prejudice and stereotyping when engaged in clinical practice.

Post-apartheid policies to address racial and gender disparities had resulted in an increased enrollment of females and students from previously disadvantaged communities in medical programs, that is, Black, Colored, and Indian.9,38,39 Although the percentage of White doctors in the public sector decreased from 45.5% to 41.8% between 2005 and 200738 and despite a 24% growth in the overall intake of females, reports persisted of a largely White, male-dominated presence at practice level by 2001.40 In fact, a report in 2008 by Breier and Wildschut estimated that it would take 22 years before females outnumbered males at practice level.38

Some female students anticipated having to overcome challenges rooted in stereotypical beliefs and stigma associated with specific racial groups stemming from South Africa’s racially divided past. Female students were aware that they will have to confront racial and gender stereotypes that cast female doctors as less competent practitioners. While female students clearly outperform their male counterparts throughout the undergraduate years,13 there is a clear need to educate the general public and patients.

While it is useful to reflect on the impact of strategies such as quotas and equity policies that have been implemented to favor entry of Black female students, it should be considered that all practices occur within a context and clinical environment where clinical supervisors, nurses, and patients need to be educated of the changing roles too. While these policies might seem effective to bring about change at medical school level, more needs to be done to educate patients and facilitate interactions within health care settings. The debate around the dual responsibility of females at home and at work and discrimination in the workplace has also not gone unnoticed.24 While great emphasis has been placed on educating about racial discrimination, it is obvious that schools should focus on discrimination in general to promote collegial and interprofessional relationships.

Limitations

The sample in this study was small and represented the views of all the racial groups in the cohort and the province of KwaZulu-Natal. The quantitative results of the study therefore cannot be extrapolated to other medical schools in the country. However, this disadvantage may be offset by the richness of the qualitative data in providing valuable information to readers and policy makers in health care education and delivery.

Conclusion

Findings from this study have shown that despite equal access, medicine in South Africa is still perceived as a male’s world and that females still faced more obstacles in training and expected these obstacles to continue in the clinical practice settings. The experiences noted especially from female students were widespread and diverse. While social redress policies have done much to increase equal access for females to medical schools, these policies, without an educational component, have done little to affect how females are perceived in the clinical practice setting and the obstacles that female students and graduates have to overcome.

Cultural values and attitudes will impact on clinical practice decisions of male and female graduands. These decisions will relate to decision about practice in private or public settings and the specialties where they choose to work. Graduates who feel valued and respected would be more likely to contribute actively to various sectors of health care services in their own countries. Perceptions of alienation, however, may result in a disillusioned work force who may feel a need to optimize their careers elsewhere in more accommodating, often more developed countries. The loss of highly skilled workers is not only further detrimental to developing countries such as ours, and repercussions greatly impact on the time and resources that are invested to train these young health professionals.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

World Health Organisation. Women’s Health Fact sheet No 3342009; March 25, 2014. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs334/en/index.html. | ||

Okereke G. Violence against women in Africa. Afr J Criminol Just Stud. 2006;2(1):1–35. | ||

Kilminster S, Downes J, Gough B, Murdoch-Eaton D, Roberts T. Women in Medicine is there a problem a literature review of the changing gender composition, structure and occupational cultures in medicine. Med Educ. 2007;41(1):39–49. | ||

Cooper L, Roter D, Johnson R, Ford D, Steinwachs D, Powe N. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907–915. | ||

Lurie N, Slater J, McGovern P, Ekstrum J, Quam L, Margolis K. Preventative care for women. Does the sex of the physician matter? N Engl J Med. 1993;12:478–482. | ||

Levinson W, Lurie N. When most doctors are women: What lies ahead? Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(6):471–474. | ||

Marcionis J, Plummer K, editors. Sociology: A Global Introduction. 4th ed. London: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2008. | ||

Van Wyk J, Naidoo S, Esterhuizen T. Will graduating medical students prefer to practise in rural communities? S Afr Fam Pract. 2010;52(2):149–153. | ||

Breier M. The Shortage of Medical Medical Doctors in South Africa. Cape Town: Human Science Research Council; 2008. | ||

Naidoo A, Naidoo SS, Gathiram P, Lalloo UG. Tuberculosis in medical doctors- a study of personal experiences and attitudes. S Afr Med J. 2013;103(3):176–180. | ||

Pratto F, Sidanius J, Levin S. Social dominance theory and the dynamics of intergroup relations: Taking stock and looking forward. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. 2006;17(1):271–320. | ||

Equal Opportunities Commission. Facts about Women and Men in Great Britain. Manchester: EOC; 2004. | ||

Heath, I. Women in medicine: continuing unequal status of women may reduce the influence of the profession. BMJ;l 329(7463): 412. (2004). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC514192/. | ||

Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine. Self Assessment Report to the Heatlh Professions Council of South Africa. Durban University of KwaZulu Natal; 2011. | ||

Sharp LK, Wang R, Lipsky MS. Perception of competency to perform procedures and future practice intent: a national survey of family practice residents. Acad Med. 2003;78(9):926–932. | ||

Nore AK. From Crafty Girl to Enthusiastic Surgeon. A Qualitative Study of Women Surgeons in Norway. Oslo: University of Oslo; 2005. | ||

Benzil DL, Abosch A, Germano I, et al. The future of neurosurgery: a white paper on the recruitment and retention of women in neurosurgery. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(3):378–386. | ||

Pelaccia, T, Delplanq H, Triby E, et al. An explanation to the underrepresentation of women in emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(7):775–779. | ||

Conrad P, Carr P, Knight S, Renfrew MR, Dunn MB, Pololi L. Hierarchy as a barrier to advancement for women in academic medicine. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19(4):799–805. | ||

Buddeberg-Fischer B, Stamm M, Buddeberg C, Bauer G, Häemmig O, Knecht M, Klaghofer R. The impact of gender and parenthood on physicians’ careers – professional and personal situation seven years after graduation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:40. | ||

Dobson R. Women doctors believe medicine is male dominated. BMJ. 1997;315(7100):80. | ||

Newton D, Grayson M, Thompson L. The variable influence of lifestyle and income on medical students’ career specialty choices: data from two US medical schools, 1998–2004. Acad Med. 2005;80(9):809–814. | ||

Dorsey ER, Jarjoura D, Rutecki GW. The influence of controllable lifestyle and sex on the specialty choices of graduating US medical students, 1996–2003. Acad Med. 2005;80(9):791–796. | ||

Brink AJ, Bradshaw D, Benade MM, Heath S. Women docots in South Africa: A survey of their experiences and opinions. S Afr Med J. 1991;80(11–12):561–566. | ||

Lambert E, Holmboe ES. The relationship between speciality choice and gender of US medical students, 1990–2003. Acad Med. 2005;80(9):797–802. | ||

Everett CB, Helmer SD, Osland JS, Smith RS. General surgery resident attrition and the 80-hour workweek. Am J Surg. 2007;14(6):751–756. | ||

Ortiz-Hernandez L, Compean-Dardon M, Gallardo-Hernandez G, Tamez-Gonzalez S, Perez-Salgado D, Verde-Flota E. Harassment experiences among students of health-related professional carees in Mexico. Gac Med Mex. 2010;146(1):25–30. | ||

Jackson I, Bobbin M, Jordan M, Baker S. A survey of women urology residents regarding career choice and practice challenges. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18(11):1867–1872. | ||

Daily News reporter: 09 Jun 16, 3:11pm Independent on-line. Available from: http://www.iol.co.za/news/crime-courts/criminals-target-on-duty-paramedics-2032786. Access date Aug 7, 2016. | ||

Wear D. Sexual harassment in academic medicine: persistence, non-reporting, and institutional response. Med Educ Online. 2005;10:10. [July 2012]. Available from: http://www.med-ed-online.org. | ||

Hintze S. ‘Am I being over sensitive?’ Women’s experience of sexual harassment during medical training. Health (London). 2004;8(1):101–127. | ||

Grant L. The gender climate of medical school: perspectives of women and men students. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1988;43(4):109–110. | ||

Davies K. Disturbing Gender. On the Doctor-Nurse Relationship. Lund: Department of Sociology, Lund University; 2001. | ||

Zelek B, Phillips SP. Gender and power: Nurses and doctors in Canada. Int J Equity Health. 2003;2(1):1. | ||

Gjerberg E, Kjolsrod L. The doctor–nurse relationship: how easy is it to be a female doctor co-operating with a female nurse. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(2):189–202. | ||

Wear D, Keck-McNulty C. Attitudes of female nurses and female residents toward each other: a qualitativestudy in one U.S. teaching hospital. Acad Everyday Work World Law Soc Enquiry. 2000;25(4):1151–1183. | ||

Hall JA, Roter DL. Do patients talk differently to male and female physicians? A meta-analytic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(3):217–224. | ||

Breier M, Wildschut A. Changing gender profile of medical schools in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2008;98(7):557–560. | ||

Breier M, Wildschut, A. Doctors in a Divided Society. The Professions and Education of Medical Practitioners in South Africa. Cape Town: HSRC; 2006. Available from: http://www.hsrcpress.ac.za/product.php?productid=2146&freedownload=1. | ||

Buch E. The Health Sector Strategic Framework: A Review. Durban: Health System Trust; 2001. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.