Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 12

Patterns of persistence with pharmacological treatment among patients with current depressive episode and their impact on long-term outcome: a naturalistic study with 5-year follow-up

Authors Li K, Tao J, Li Y, Chen M, Wu X, Liao Y, Lin X, Gan Z

Received 27 December 2017

Accepted for publication 2 March 2018

Published 3 May 2018 Volume 2018:12 Pages 681—693

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S160767

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Naifeng Liu

Kanglai Li,1,* Jiong Tao,2,* Yuemei Li,3 Minhua Chen,2 Xiuhua Wu,2 Yingtao Liao,2 Xiaolan Lin,4 Zhaoyu Gan2

1Department of Very Important Patient, the 3rd Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Psychiatry, the 3rd Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China; 3Department of Obstetrics, Wuzhou Gongren Hospital, Wuzhou, People’s Republic of China; 4Department of Infectious Diseases, the 3rd Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Background: The aim of the study was to describe and compare the patterns of medication persistence among patients with unipolar depression (UD) or bipolar depression in a 5-year follow-up, and explore their impact on long-term outcome.

Patients and methods: A total of 333 eligible patients with current major depressive episode were observed and followed up from the first index prescription for 5 years. Lack of persistence or treatment interruption was defined as a gap of at least 2 consecutive months without taking any medication. Time to lack of persistence in the first (TLP1) and the second (TLP2) episode of treatment, number of visits before the first treatment interruption (NV) and number of treatment interruptions (NTI) were measured.

Results: During the 5-year follow-up, nearly 50% of patients experienced at least two times of treatment interruption. Pattern of medication persistence did not significantly differ between UD and bipolar disorder (BD) patients. TLP1 was positively associated with TLP2. Shorter TLP1 predicted a higher possibility of subsequent visits because of recurrence or relapse and more NTI meant a lower likelihood of achieving full remission in the fifth year for both UD and BD patients. For UD patients, shorter TLP1 or less NV predicted a lower chance of achieving remission, while for BD patients, shorter TLP1 meant an earlier subsequent visit and more NTI predicted a lower possibility of achieving remission.

Conclusion: Pattern of medication persistence was similar but its impact on the long-term outcome was quite different between UD and BD.

Keywords: adherence, pharmacotherapy, bipolar disorder, depression, rehabilitation

Introduction

Major depressive episode (MDE) is a very common and severe condition shared by unipolar depression (UD) and bipolar disorder (BD) and is the primary reason that patients with UD or BD seek medical help. Treatment with medication, so far, is still the most effective method to cure and prevent MDE from recurring or becoming chronic.1,2 Therefore, treatment guidelines recommend a continuation of treatment after an initial response for 4–9 months and maintenance treatment of 2 years or longer in the case of recurrent major depressive disorder.3 However, previous studies have shown that the rates of adherence to medication among patients with MDE are less than optimal. For instance, in our previous study,4 more than 60% patients with MDE abandoned medication treatment within 12 months after treatment initiation, and over 40% gave up treatment in the first 3 months. Similar treatment discontinuation rates are also seen in other studies.5,6

However, most of the studies about persistence with pharmacological treatment focused on the first episode of medication treatment. That is to say, once medication treatment is discontinued, the follow-up also ends, and little further effort is made to investigate what happens next. Although it is well documented that early treatment discontinuation is associated with a higher risk of recurrence or relapse7,8 for patients with MDE, the relationship between treatment discontinuation and relapse or recurrence is still unclear. On the one hand, recurrence or relapse might be independent of medication maintenance treatment,9 or for some patients with bipolar depression, long-term antidepressant treatment might trigger a manic episode9,10 or emotional instability.11 On the other hand, studies on the association between treatment discontinuation and relapse or recurrence usually focus on patients who achieve remission from acute-stage treatment. Few studies pay attention to those who do not respond well or adhere to the initial treatment. In addition, treatment discontinuation not only means the end of treatment, it also reflects the patients’ behavior pattern in response to mental disorder and medication treatment, which might be implicated in the patients’ personality.12 On these grounds, initial patterns of medication persistence might not only predict long-term outcome of the illness, but may also predict subsequent patterns of help-seeking behavior. In order to examine this hypothesis, a 5-year follow-up study was performed on a sample of patients with a current depressive episode. As far as we know, no similar study has been done before.

Patients and methods

Subjects

Participants from our previous study were included in this study.4 They were experiencing a current MDE which met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria, were seeking medication treatment for the first time, aged between 16 and 65 years. All patients and their legal guardians provided written informed consent. The clinical characteristics of all participants have been described elsewhere.4 All procedures used in the present study were reviewed and approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University.

Measurement

Baseline evaluation

At baseline, data on demographic and clinical characteristic (for detailed information see Table 1) were collected with self-administered questionnaires. Initial diagnosis, current and lifetime comorbidity were assessed with the Chinese version of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV-TR Axis 1 Disorders (SCID-I).

Pattern of persistence with pharmacological treatment measurement

The assessment of persistence with pharmacological treatment was based on the outpatient medical files, which were kept in our outpatient department, electronic records of prescription and the patients’ self report about whether and when they stopped the prescribed medication. If a patient did not show up for 2 or more months after the scheduled appointment, an interview was arranged with the study team members on the subsequent visit or by the end of 5-year follow-up via telephone to ask when the pharmacological treatment was stopped. Medication treatment interruption or lack of persistence with pharmacological treatment is defined as a gap of at least 2 consecutive months without taking any medication. Justification for this definition is given in detail in our previous study.4 Correspondingly, an episode of medication treatment is defined as a consecutive course of treatment without medication treatment interruption. Adherence to medication is measured in two ways: first, time to lack of persistence (TLP) is calculated from the date of the first prescription to the date when pharmacological treatment is actually discontinued. TLP in the first episode of treatment is called TLP1, and the TLP in the second episode of treatment is named as TLP2. Second, the number of visits (NV) is counted from the baseline to the last visit before the first treatment interruption. Subsequent help-seeking behavior is assessed in two ways: the first is time to subsequent visit (TSV), which is calculated from the date of the first treatment interruption to the date of subsequent visit; the second is number of treatment interruptions (NTI), or number of gaps of at least 2 consecutive months without taking any medication during the 5-year follow up. Since persistence with medication treatment is the target outcome of this study, subsequent visit only for health consultation is not included. For example, a visit would not be counted in the case that a patient comes back only to discuss whether it is advisable to become pregnant after discontinuing medication treatment for several months. However, if a patient goes to other medical institutes to refill the medication or to seek pharmacological treatment during the follow-up, his or her medication treatment in the other medical institutes is treated in the same way as in our department.

Long-term outcome measurement

The assessment of long-term outcome was performed at the end of the 5-year follow-up in the following ways: the presence or absence of symptoms in the fifth year of the study was evaluated with Hamilton Depression Rating Scale 24-Item (HAMD-24) and Young Mania Rating Scale (presence was defined as score on the corresponding item >2, and absence was defined as score on the corresponding item ≤2). Relapse/recurrence and current depressive status were established with the section Mood episode and mood disorders from the Chinese version of the SCID-I. The subjects’ outpatient medical files were also checked to confirm whether they experienced any mood-related symptom or mood episode in the fifth year of follow-up. DSM-IV-TR criteria was employed to determine the state of the illness, but the criteria for full remission were more stringent in this study, requiring not only the absence of all 9 core depressive or manic symptoms in the DSM-IV-TR criteria, but also the absence of any somatic symptoms (including somatic anxiety, fatigue or pain and physical complaints in HAMD-24), since somatic symptoms are the most common residual symptoms of MDE after pharmacological treatment, and predict higher risk of relapse and poorer prognosis.13,14 Furthermore, in some cases, somatic symptoms are the primary reason that drives depressive patients to seek medical help, especially in Asian population.15 In addition, the duration of the asymptomatic period for remission is required to last at least 1 year instead of 2 months because 2 months is too short to be accurately recalled in a 5-year follow-up and to define recovery.16 More importantly, a higher degree of consistency of remission patterns over time means a greater prognostic significance in severe mood disorder.17 Therefore, the long-term outcome is based on the participants’ conditions in the fifth year and is divided into five categories: 1) full remission, which means the participant is free of any mood-related symptom in the fifth year; 2) partial remission, which means that in the fifth year, the participant does not experience any episode of depression, mania/hypomania, or mixed states but some residual symptoms are still present; 3) recurrence, which means that in the final year of follow-up, the participant experiences at least one episode of depression, mania/hypomania or mixed states but at some period of time, they can achieve full or partial remission; 4) chronicity, which means that in the fifth year, the participant has been ill and never experienced any kind of remission; 5) dead, which means that available information shows that the participant died during 5-year follow-up.

Recruitment and follow-up

A flowchart of the recruitment and the 5-year follow-up is given in Figure 1.

| Figure 1 Flowchart of this study. |

At baseline, potential participants were found and recommended by their first visiting psychiatrists. In total, 352 potential patients were screened and 333 patients were eligible to be enrolled in this study.

At the end of 1-year follow-up, 187 patients with BD and 146 patients with UD were interviewed in our psychiatric clinic or over telephone. Among the 187 patients with BD, 62 (43.9%) were initially misdiagnosed as UD by their first treating psychiatrists, and the diagnosis of 25 (13.4%) were revised from UD to BD because of newly detected manic or hypomanic episodes. Of the 146 patients with UD, 16 (11.0%) were initially misdiagnosed as BD by their first treating psychiatrists.

At the 5-year follow-up interview, 73 (21.9%) were out of contact and 13 (3.9%) refused to be interviewed; therefore, 247 (74.2%) patients were finally available for interview. Considering the high proportion of missing patients at the 5-year interview, comparison of clinical characteristics was done between missing patients with those who finished the study. The results showed that compared to those who finished the study, the missing patients were more likely to experience their current MDE in the spring (OR: 4.907, 95% CI 1.845–13.051, P=0.001) or autumn (OR: 3.389, 95% CI 1.186–9.684, P=0.023), less likely to be misdiagnosed by their treating psychiatrists (OR: 0.372, 95% CI 0.207–0.667, P=0.001), or have a comorbidity of anxiety disorder (OR: 0.354, 95% CI 0.182–0.686, P=0.002), have a shorter TLP1 (OR: 0.925, 95% CI: 0.898–0.953, P=2.3e–7) and experienced less NTI (OR: 0.558, 95% CI: 0.455–0.699, P=2.6e–7). No significant difference was found between them with regard to onset age, age, sex, risk of suicide, number of depressive episodes, duration of current MDE, comorbidity of substance abuse or physical illness, and diagnosis.

Procedures

Prior to the start of this study, three psychiatrists (JT, XHW, ZYG) attended a training program focused on diagnosing BD and depression. At the end of the program, their kappa coefficient reached 0.94 in terms of interrater reliability. Throughout the whole study period, all diagnostic interviews and assessments were performed by these three psychiatrists, who already constituted a special committee responsible for these tasks.

At baseline, all the eligible participants were asked to finish the abovementioned baseline evaluation. Once the first medication prescription for their MDE was prescribed, their persistence with treatment was monitored by reception nurse and their visiting psychiatrists. If a participant was found not to show up at least 2 months later than the latest scheduled medication refilling, an interview was arranged at the subsequent visit if it happened, aiming to make sure when the medication treatment actually took place. In addition, another interview was scheduled at 1 year and 5 years in person or over the telephone for all participants. During the interview, a retrospective life chart was used to record when and how many times medication treatment interruption occurred during the whole period of follow-up and when the subsequent visit occurred after the first treatment interruption. During the period of follow-up, if a suspected switch, which means switch from depressive episode to hypomanic episode, was detected, the patients’ relatives or friends were asked to provide additional information.

At the end of the study, the abovementioned committee reviewed all the data collected in the whole period of follow-up and came up with a final diagnosis according to the criteria of DSM-IV-TR about UD and BD. Differential diagnosis between UD and BD was not made until 5 years after entry into this study. This is because some cases have not yet experienced any manic or hypomanic episode at baseline, although they are BD sufferers.18

During the study period, all treatment decisions or changes in treatment medications such as dose reduction, dose augmentation, switch and discontinuation strategies were made by their treating psychiatrists and the participants. This study was carried out under naturalistic clinical settings.

Statistics

Univariate analyses were conducted using Student’s t-test, the Mann–Whitney U-test, Wilcoxon signed rank test or Pearson’s χ2 test. Relationship of two variables was tested with correlation analysis. Simple line charts were plotted to describe the distribution of the time when the participants discontinued the treatment. Pie charts were drawn to reflect the proportion of patients with different long-term outcome. Univariate binary logistic regression was performed to explore the predictors of subsequent visit after the first treatment interruption and univariate Cox regression analysis was conducted to further investigate potential predictors of TSV. The results were considered significant at P<0.05. Data management and statistical analyses were carried out using commercial statistical package SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Pattern of persistence with pharmacological treatment in the first episode of treatment

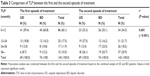

Of the 333 eligible participants, 126 (86.3%) UD patients and 165 (88.2%) BD patients experienced at least one time of the defined treatment interruption in the 5-year follow-up. TLP and NV before the first treatment interruption are listed in Table 2, from which we can see that nearly half of the UD or BD patients discontinued their medication treatment within the first 3 months, and about one-fifth of them abandoned the medication after the first visit. The median of TLP1 was 6.0 months and 4.0 months for UD and BD patients, respectively, while the median of NV was 7 times for both UD and BD patients.

| Table 2 Pattern of medication persistence in the first period of treatment |

About half of UD (51.4%) or BD (44.3%) patients experienced treatment interruption at least twice in the 5-year follow-up, and about one quarter of them (UD: 16.5%; BD: 12.8%) discontinued their pharmacological treatment for five or more times during the same period. By contrast, there was another nearly one quarter of UD (12.3%) or BD (11.8%) patients who did not experience any treatment interruption in the 5-year follow-up. No significant difference in NTI was found between UD and BD (P>0.05).

More than 40% of UD (42.7%) or BD (48.1%) patients came back to medication treatment within half a year after the first treatment interruption, and more than three quarters of them (UD: 76%; BD: 77.7%) returned to pharmacological treatment within 1 year. Among 75 UD patients who returned to medication treatment after the first treatment interruption, all were in a depressive state. Of the 81 BD patients who returned after the first treatment interruption, 55 (67.9%) were in a depressive state, 18 (22.2%) were in mixed states and 8 (9.9%) were in a manic state. That is to say, all the subsequent visits were due to recurrence or relapse, and most of the recurrence or relapse happened within 1 year after the first treatment interruption.

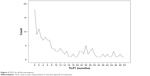

Association of TLP1 and TLP2

For UD patients, the median of TLP1 and TLP2 was 9 months and 18 months, respectively. Wilcoxon signed ranks test showed they were significantly different (z=−9.096, P=9.4e–20). For BD patients, the median of TLP1 and TLP2 was 7 months and 23 months, respectively, which was also significantly different (z=−6.455, P=1.1e–10). That is to say, for both UD patients and BD patients, TLP1 was significantly longer than TLP2. However, chi-square test showed no significant difference in TLP between UD and BD, no matter in the first or the second episode of treatment (P>0.05) (Table 3). Therefore, UD and BD were combined in further analyses. As seen in Figures 2 and 3, patterns of persistence with pharmacological treatment were different between the first and the second episode of treatment. In the first episode of treatment, the rate of treatment discontinuation decreased with time and more than half of the treatment discontinuation occurred in the first year, while in the second episode of treatment, the rate of treatment discontinuation went up and down during the 5-year follow-up, but was relatively even in each year. Chi-square test showed that the distribution of TLP between the first and the second episode of treatment was significantly different (χ2=33.64, df=3, P=2.4e–7). Compared to the first year of the second treatment episode, the hazard ratio of discontinuing the treatment in the first year of the first episode treatment was 4.171 (95% CI: 2.491–6.986). Correlation analysis further demonstrated that TLP1 and TLP2 were significantly associated with each other (r=0.681, P=5.6e–24), indicating that the pattern of persistence with pharmacological treatment at the first episode of treatment could impact the subsequent pattern of persistence with pharmacological treatment after the first treatment interruption.

| Figure 2 TLP1 for all the participants. |

| Figure 3 TLP2 for all the participants. |

Predictors of subsequent visit after the first treatment interruption

In order to explore the potential predictors of subsequent visit after the first treatment interruption, univariate binary logistic regression was performed. At this step, except those who experienced no treatment interruption, all the eligible participants were included in the analysis.

As shown in Table 1, TLP1 was a negative predictor of the subsequent visit after the first treatment interruption for both UD and BD patients. That is to say, the shorter the TLP1, the sooner the subsequent visit. Interestingly, the other predictors of subsequent visits were completely different between UD and BD patients. For UD patients, risk factors of subsequent visit included high risk of suicide, comorbidity of anxiety disorders or somatic symptoms. For BD patients, hospitalization after the first visit, initially being misdiagnosed and less NV were all risk factors for subsequent visits, while history of spontaneous remission or switch was a protective factor.

To further explore the predictors of TSV, univariate Cox regression analysis was performed with TSV as the dependent variable and factors listed in Table 1 as independent variables. For both BD and UD patients, none of the abovementioned factors were found to predict TSV. But for BD patients, when TLP1 was treated as a category variable (1=0–3 months, 2=3–6 months, 3=6–9 months, 4=9–12 months, 5=12 months or more), the predictive effect reached significance (P=0.020, OR=1.158, 95% CI: 1.023–1.311). In addition, if medication persistence was measured with NV before the first treatment interruption, it could also act as a predictor of TSV (P=0.029, OR=1.016, 95% CI: 1.002–1.031). However, similar findings were not seen in UD patients.

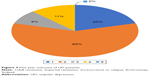

Five-year outcome and its predictors

Figures 4 and 5 demonstrate the proportion of each 5-year outcome for patients with UD or BD, respectively. Chi-square test showed no significant difference in the 5-year outcome between UD and BD (P>0.05).

| Figure 4 Five-year outcome of UD patients. |

| Figure 5 Five-year outcome of BD patients. |

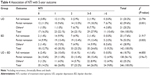

Table 4 lists the distribution of the 5-year outcome based on different levels of treatment interruption in the 5-year follow-up, indicating that the more the NTI in the 5-year follow-up, the less likely full remission was achieved. Chi-square test showed that the distribution of 5-year outcome in different levels of treatment interruption was significantly different for both UD (χ2=23.794, P=0.001) and BD (χ2=21.917, P=0.003) patients. Spearman’s correlation analysis showed that the ranks of 5-year outcome were significantly associated with the levels of treatment interruption for both UD (r=0.380, P=0.00007) and BD (r=0.298, P=0.003) patients.

Univariate binary logistic regression, with 5-year outcome as a dependent variable (full remission=1, otherwise=0) and NTI as an independent variable, showed that NTI was a negative predictor of full remission for both UD patients (P=0.004, OR=0.564, 95% CI: 0.380–0.836) and BD patients (P=0.019, OR=0.680, 95% CI: 0.492–0.939). If the 5-year outcome was focused on remission, including full remission and partial remission, univariate binary logistic regression was conducted again, but this time, the dependent variable was treated in the following way: full remission or partial remission=1, otherwise=0. For UD patients, only TLP1 (P=0.024, OR=0.946, 95% CI: 901–993) and NV (P=0.017, OR=0.0934, 95% CI: 0.882–0.988) in the first episode of treatment were the predictors of remission in the fifth year of the follow-up. In order to explore the impact of dropout at different time points on long-term outcome, TLP1 was treated as a binary variable based on the following cutoff points: 3 months, 6 months, 9 months and 12 months; then the abovementioned univariate binary logistic regression with full/partial remission or not as outcome variable was performed again. The corresponding odds ratios were 4.750 (95% CI: 1.621–13.919, P=0.005), 4.887 (95% CI: 1.693–14.104, P=0.003), 4.667 (95% CI: 1.520–14.324, P=0.007) and 5.833 (95% CI: 1.566–21.717, P=0.009), respectively. In other words, if UD patients dropped out within 3 months, 6 months, 9 months or 12 months, the risk of failure to remit in the fifth year would be 4.750-, 4.887-, 4.667-, or 5.833-fold higher than those who dropped out after 3 months, 6 months, 9 months or 12 months pharmacological treatment, respectively. For BD patients, the predictors of remission in the fifth year included trigger factors (P=0.018, OR=3.443, 95% CI: 1.238–9.586), onset in spring (P=0.037, OR=0.286, 95% CI: 0.088–0.927), hypersomnia (P=0.049, OR=0.431, 95% CI: 0.186–0.997), and NTI (P=0.005, OR=0.784, 95% CI: 0.662–0.930).

Discussion

Pattern of persistence with pharmacological treatment in 5 years

Our previous study has described the pattern of persistence with pharmacological treatment following the first episode of treatment (Table 2) and explored its predictors among patients with current MDE. In this study, we further investigated the pattern of persistence with pharmacological treatment in a 5-year follow-up study. We found that about 12% participants adhered to pharmacological treatment in the 5-year follow-up, roughly 40% never came back to medication treatment in 5 years after a short or long episode of medication treatment and nearly 50% experienced at least two times of treatment interruption in 5 years. The long-term pattern of persistence with pharmacological treatment did not significantly differ between UD and BD patients. Although no prior studies have ever examined the long-term pattern of persistence with pharmacological treatment among patients with MDE, recurrence or relapse rates of 40%–90% in 2–5 years among UD or BD patients reported from naturalistic prospective studies19–21 imply a similar long-term pattern of medication persistence with this study.

Association of the pattern of medication persistence between the first and the second episode of treatment

In this study, TLP2 was found to be longer than TLP1, meaning that medication persistence in the second episode of treatment was generally better than during the period when medication was initiated. Possible reasons for this might include lessons learned from experience and suggestions indirectly from the related treatment guidelines, like the CANMAT guidelines22,23 and NICE guidelines,24 which recommend a longer duration of medication treatment for recurrent UD or BD patients than for the first-episode UD or BD patients. This result can also partly explain why medication persistence varies with studies that started from different phases of treatment.6,25–27

Although TLP2 was different form TLP1, as seen in Table 3, they were positively associated with each other. In other words, the shorter the TLP1 is, the earlier the patient discontinues the medication treatment in the second episode of treatment. Such relationship is in line with a previous report that claimed patients who returned to treatment after abandoning treatment had a high likelihood of discontinuing again.28

As demonstrated previously,28–30 longer duration of initial treatment helped decrease the risk of recurrence or relapse for UD patients. Our study partly replicated such finding not only among UD patients from Chinese population, but also among BD patients. Moreover, we found that duration of initial treatment predicted TSV due to recurrence or relapse. It was reported that poor adherence to medication was associated with a high recurrence31 and treatment discontinuation by the patients was significantly associated with time to recurrence or relapse in BD patients,20 but the relationship of duration of initial treatment with subsequent visit due to relapse or recurrence has been rarely explored among BD patients.32 Considering that a large number of patients with depression do not seek medical help even if their depressive symptoms recur,33 predictors of recurrence or relapse is not equivalent to predictors of subsequent visit due to recurrence or relapse. As shown in Table 1, a number of factors determine whether the patients would return to medication treatment when the illness recurred or relapsed after the first treatment interruption. Furthermore, the predictive model of subsequent visit was found to be different between UD and BD patients. We are not aware of prior studies that have ever explored and compared such predictive model between UD and BD patients. Although our previous study found that predictors of premature dropout differed between UD and BD,4 in the absence of replicating data, it is still premature to extensively speculate that such difference reflects different nature of these two diseases.

Impact of pattern of medication persistence on long-term outcome

With a stricter definition of remission and a more detailed categorization of long-term outcome, our study showed that the 5-year outcome of UD and BD patients was similar: in the fifth year of follow-up, nearly 20% achieved full remission, about 50% were in partial remission and roughly 30% experienced index or chronic episode of affective disorder or died. Compared to a previous prospective study with the same period of follow-up,34 which claimed chronicity was rare among BD patients, patients characterized with chronicity accounted for 18%. Moreover, the full remission rate in our study was far less than the 96% reported in that study.34 Differences might be attributed to a more stringent definition of remission and more representative sample in this study. However, our study partly replicated findings from a naturalistic observation study that reported a full remission rate of 26% and partial remission rate of 45% within 12 months among depression patients,35 implying the long-term outcome of UD or BD patients is far from optimistic.

As expected, our study confirmed that persistence with pharmacological treatment imposed a great impact on the long-term outcome, but such impact seemed to be similar but not identical between UD and BD patients. On the one hand, for both UD and BD patients, NTI is a negative predictor of full remission. On the other hand, predictors of remission differs a lot between UD and BD: for UD patients, shorter TLP1 and less NV in the first episode of treatment predict less chance of achieving remission, while comorbidity of physical illness predicts more likelihood of getting full remission; for BD patients, the positive predictors of remission include trigger factor and onset in spring, and the risk factors of not achieving remission were hypersomnia and more NTI. In terms of persistence with pharmacological treatment, the same index of persistence with pharmacological treatment has different implication of long-term outcome for UD and BD patients. For example, TLP1 is a negative predictor of remission for UD patients, but for BD patients, it can predict TSV instead of remission. Another example is NTI, for BD patients, it can predict both full remission and partial remission, but for UD patients, it can only predict full remission. As far as we know, it is the first time that a different impact pattern of persistence with pharmacological treatment on long-term outcome between UD and BD has been reported.

Limitation

Our findings are subject to a number of limitations. First, about one quarter of participants lost contact at the final interview, although extensive efforts were made to contact the participants and all the available information including medical records, electronic prescription and interview with the participants’ family members was used to the fullest extent. As a consequence, our findings are subject to potential selection bias. Comparison of baseline clinical characteristics between the missing participants and those who finished the study showed that the missing participants were less likely to have a comorbid anxiety disorder and to be misdiagnosed, to have dropped out earlier (median TLP1: 1.0 month vs 11.0 months) and were less likely to come back to treatment after discontinuing the initial treatment (88.6% vs 22.0%) than those who finished the study, indicating they might be the ones whose conditions are less severe and less complicated. In this case, the 5-year outcome might be more optimistic than what the results showed, and the association between pattern of persistence with pharmacological treatment and long-term outcome should be limited to those who actually received medication treatment. In addition, it is possible that those patients we lost contact with went to other medical institutes for medical treatment. However, this possibility is very small, since our department has the highest reputation in this area in Guangdong province and most of the missing participants were local residents, as confirmed by interview at the 1-year stage. Second, only treatment interruption lasting at least 2 consecutive months was investigated in this study. Therefore, we do not know the pattern of treatment discontinuation lasting less than 2 months and its impact on the long-term outcome among patients with current MDE from this study. Third, detailed information about the participants’ pharmacological treatment was not collected and examined in this study; so, we do not know what kind of treatment really takes effect in preventing patients from recurrence or relapse. In our previous study,4 we found that misdiagnosis as depression was a protective factor of premature dropout for BD patients, indicating antidepressants seemed to help improve persistence with pharmacological treatment among BD patients. However, in this study, misdiagnosis as depression was found to predict higher possibility of subsequent visits due to recurrence or relapse, implicating antidepressants used in BD patients might have a negative long-term effect. This controversy conclusion about the effect of antidepressants suggests that we should sometimes take enough time to objectively evaluate a drug’s role. Fourth, persistence with pharmacological treatment and outcome measurement were partly based on retrospective interview, even over telephone for those who did not come back to treatment. Although other information like medical records, electronic prescription and interview with family members would help increase the accuracy of the related information, a recall bias might still be affecting our results. Fifth, only BD patients who sought medical help due to a first depressive episode were studied and so conclusions drawn from BD patients in this study should not be generalized to BD patients who seek medical help due to manic or mixed episode for the first time. Finally, patients enrolled in this study all came from the Psychiatric Department of the 3rd Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University, which differs from other mental health institutions in terms of treatment provision and academic reputation. Though we do not know what these differences mean for treatment persistence, we caution against generalizing conclusions to depressive patients seeking medical treatment in other mental health institutions.

Conclusion

Patients with UD share a similar pattern of medication persistence with BD patients in a 5-year follow-up. The pattern of medication persistence in the first episode of treatment imposes a great impact on the subsequent medication persistence, but its influence on the long-term outcome is quite different between UD and BD.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (201609010086), the Nursing Fund of the 3rd Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University (201607), the Undergraduate Teaching Reform Project of Sun Yat-Sen University (2016140) and the 3rd Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University, Clinical Research Program. The abovementioned funding bodies had no further role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Professor Jonathan Flint in editing this paper and the efforts of all of the nurses, technicians and patients who participated in this study.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Sim K, Lau WK, Sim J, Sum MY, Baldessarini RJ. Prevention of relapse and recurrence in adults with major depressive disorder: systematic review and meta-analyses of controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;19(2):pyv076. | ||

Glue P, Donovan MR, Kolluri S, Emir B. Meta-analysis of relapse prevention antidepressant trials in depressive disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(8):697–705. | ||

Bauer M, Pfennig A, Severus E, Whybrow PC, Angst J, Möller HJ; World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry. Task Force on Unipolar Depressive Disorders. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of unipolar depressive disorders, part 1: update 2013 on the acute and continuation treatment of unipolar depressive disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013;14(5):334–385. | ||

Li K, Wei Q, Li G, He X, Liao Y, Gan Z. Time to lack of persistence with pharmacological treatment among patients with current depressive episodes: a natural study with 1-year follow-up. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:2209–2215. | ||

Conti V, Lora A, Cipriani A, Fortino I, Merlino L, Barbui C. Persistence with pharmacological treatment in the specialist mental healthcare of patients with severe mental disorders. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68(12):1647–1655. | ||

Olfson M, Marcus SC, Tedeschi M, Wan GJ. Continuity of antidepressant treatment for adults with depression in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):101–108. | ||

Altshuler L, Kiriakos L, Calcagno J, et al. The impact of antidepressant discontinuation versus antidepressant continuation on 1-year risk for relapse of bipolar depression: a retrospective chart review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(8):612–616. | ||

Kim KH, Lee SM, Paik JW, Kim NS. The effects of continuous antidepressant treatment during the first 6 months on relapse or recurrence of depression. J Affect Disord. 2011;132(1–2):121–129. | ||

Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1905–1917. | ||

Post RM, Altshuler LL, Frye MA, et al. Rate of switch in bipolar patients prospectively treated with second-generation antidepressants as augmentation to mood stabilizers. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3(5):259–265. | ||

Altshuler LL, Post RM, Leverich GS, Mikalauskas K, Rosoff A, Ackerman L. Antidepressant-induced mania and cycle acceleration: a controversy revisited. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(8):1130–1138. | ||

Sumin AN, Raih OI. [Influence of type D personality on adherence to treatment in cardiac patients]. Kardiologiia. 2016;56(7):78–83.Russian. | ||

Paykel ES, Ramana R, Cooper Z, Hayhurst H, Kerr J, Barocka A. Residual symptoms after partial remission: an important outcome in depression. Psychol Med. 1995;25(6):1171–1180. | ||

Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Maser JD, et al. Major depressive disorder: a prospective study of residual subthreshold depressive symptoms as predictor of rapid relapse. J Affect Disord. 1998;50(2–3):97–108. | ||

Weiss B, Tram JM, Weisz JR, Rescorla L, Achenbach TM. Differential symptom expression and somatization in Thai versus U.S. children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(5):987–992. | ||

Furukawa TA, Fujita A, Harai H, Yoshimura R, Kitamura T, Takahashi K. Definitions of recovery and outcomes of major depression: results from a 10-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117(1):35–40. | ||

Goldberg JF, Harrow M. Consistency of remission and outcome in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders: a 10-year prospective follow-up. J Affect Disord. 2004;81(2):123–131. | ||

Perlis RH, Miyahara S, Marangell LB, et al; STEP-BD Investigators. Long-term implications of early onset in bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD). Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(9):875–881. | ||

Ramana R, Paykel ES, Cooper Z, Hayhurst H, Saxty M, Surtees PG. Remission and relapse in major depression: a two-year prospective follow-up study. Psychol Med. 1995;25(6):1161–1170. | ||

Simhandl C, König B, Amann BL. A prospective 4-year naturalistic follow-up of treatment and outcome of 300 bipolar I and II patients. J Clin Psychiatr. 2014;75(3):254–262. | ||

Van Londen L, Molenaar RP, Goekoop JG, Zwinderman AH, Rooijmans HG. Three- to 5-year prospective follow-up of outcome in major depression. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):731–735. | ||

Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, O’Donovan C, et al; Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: consensus and controversies. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(Suppl 3):5–69. | ||

Lam RW, Kennedy SH, Grigoriadis S, et al; Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) Clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults: III. Pharmacotherapy. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(Suppl 1):S26–S43. | ||

Goldberg D. The “NICE Guideline” on the treatment of depression. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2006;15(1):11–15. | ||

Muzina DJ, Malone DA, Bhandari I, Lulic R, Baudisch R, Keene M. Rate of non-adherence prior to upward dose titration in previously stable antidepressant users. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1–2):46–52. | ||

Kogut S, Quilliam BJ, Marcoux R, et al. Persistence with newly initiated antidepressant medication in Rhode Island Medicaid: analysis and insights for promoting patient adherence. R I Med J (2013). 2016;99(4):28–32. | ||

Sajatovic M, Valenstein M, Blow F, Ganoczy D, Ignacio R. Treatment adherence with lithium and anticonvulsant medications among patients with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(6):855–863. | ||

Moisan J, Grégoire JP. Patterns of discontinuation of atypical antipsychotics in the province of Québec: a retrospective prescription claims database analysis. Clin Ther. 2010;32 Suppl 1:S21–S31. | ||

Baldessarini RJ, Lau WK, Sim J, Sum MY, Sim K. Duration of initial antidepressant treatment and subsequent relapse of major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(1):75–76. | ||

Viguera AC, Baldessarini RJ, Friedberg J. Discontinuing antidepressant treatment in major depression. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1998;5(6):293–306. | ||

Gutiérrez-Rojas L, Jurado D, Martínez-Ortega JM, Gurpegui M. Poor adherence to treatment associated with a high recurrence in a bipolar disorder outpatient sample. J Affect Disord. 2010;127(1–3):77–83. | ||

Geoffroy PA, Bellivier F, Henry C. [Treatment of manic phases of bipolar disorder: critical synthesis of international guidelines]. Encephale. 2014;40(4):330–337. French. | ||

Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):8–19. | ||

Pallaskorpi S, Suominen K, Ketokivi M, et al. Five-year outcome of bipolar I and II disorders: findings of the Jorvi Bipolar Study. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(4):363–374. | ||

Johansson O, Lundh LG, Bjarehed J. 12-month outcome and predictors of recurrence in psychiatric treatment of depression: a retrospective study. Psychiatr Q. 2015;86(3):407–417. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.