Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 14

Patient Satisfaction and Food Waste in Obstetrics And Gynaecology Wards

Authors Schiavone S , Pistone MT, Finale E , Guala A, Attena F

Received 3 April 2020

Accepted for publication 7 July 2020

Published 5 August 2020 Volume 2020:14 Pages 1381—1388

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S256314

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Sara Schiavone, 1 Maria Teresa Pistone, 1 Enrico Finale, 2 Andrea Guala, 2 Francesco Attena 1

1Department of Experimental Medicine, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Naples 80138, Italy; 2Department of Maternal and Child Health, ASL Verbano Cusio Ossola, Omegna, VB 28887, Italy

Correspondence: Francesco Attena

Department of Experimental Medicine, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Via Luciano Armanni, 5, Naples 80138, Italy

Tel +39 081 5666012

Email [email protected]

Introduction: Patient satisfaction is an indicator of healthcare quality, and expectation is an important determinant. A component of patient satisfaction is the quality of foodservice. An indicator of this quality is the food wasted by hospitalised patients. In the present study, we investigated patient satisfaction regarding food and foodservice, the expectation on food quality and the amount of food wasted in two obstetrics and gynaecology wards in Northern and Southern Italy.

Patients and Methods: A questionnaire, including sociodemographic data, rate of food waste, expectations of food quality and characteristics of food and foodservice, was administrated to 550 inpatients in obstetrics and gynaecology wards (275 for each hospital). Univariate analysis was performed to describe the results, and multivariate analysis was carried out to control for sociodemographic data.

Results: Northern patients were more satisfied with the quality of food (54.2% vs 36.0%) and foodservice (54.5% vs 38.2%) than southern patients. Northern patients had more positive expectations about the quality of food (69.5% vs 31.6%), whereas southern patients stated that they had no expectations. Southern patients gave more importance to mealtime (72.7% vs 26.2%), and many of them brought food from home to the hospital (30.2% vs 2.2%) through relatives who came to visit them. Southern patients discarded about 41.7% of food served, whereas northern patients discarded only about 15.3%.

Discussion: Food waste is a worldwide problem due to its economic, social and environmental effects. Especially in hospitals, food waste could have a negative impact on the overall patient satisfaction.

Keywords: food quality, food service, hospital, food waste, patient satisfaction

A Letter to the Editor has been published for this article.

Introduction

Patient satisfaction is a well-known and widely used indicator in evaluation of healthcare quality.1,2 Nevertheless, the studies showed heterogeneity and variability in design and data interpretation, especially since the potential determinants of patient satisfaction are many and varied among the studies.2 Among these determinants, expectation is one of the most important.3 Evaluating and understanding patient expectation is therefore essential for health care providers. However, many studies on patient expectations have highlighted the complexity of expectation measurement and its impact on satisfaction.4

One component of patient satisfaction is the quality of the food served and the foodservice, and an indicator of this quality is the food wasted by patients during their hospitalisation. The quality of hospital foodservice is one of the most relevant items of health care quality perceived by patients and by their families.5 Food waste means food appropriate for human consumption which is discarded, even after its storage beyond its expiry date, or left to spoil.6 In addition to spoiled food, other reasons may be possible, such as oversupply of the food service or individual consumer eating habits.7

In recent years, food waste has received great attention.8 More than one billion tons of food is lost or wasted each year worldwide, representing one third of all food produced for human consumption as described in the latest report of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.9 The amount of food waste varies between countries, and is influenced by income level, urbanization and economic growth.10,11 In Italy, many initiatives have been undertaken to reduce food waste: encouraging the recovery of food through charitable donations, promoting the benefits of a healthy lifestyle to students and promoting collaborations with public institutions (such as schools, hospitals and public companies) to prevent and reduce food-related waste.12–14

In the present study, we investigated patient satisfaction regarding food and foodservice, the expectation on food quality and the amount of food wasted in obstetrics and gynaecology wards of one hospital in Northern Italy and one hospital in Southern Italy.

Materials and Methods

Setting

This cross-sectional study used data provided by inpatients in two hospitals: one in Campania, a region in the south of Italy, and the other in Piedmont, in the north of Italy in the period between December 2018 and April 2019. This study is a part of a research conducted to assess hospital food waste and the study protocol was also published elsewhere.15 To standardize for a selected and similar population in both hospitals, the study was carried out in the obstetrics and gynaecology wards.

Both hospitals had similar modalities to serve food. They outsourced their kitchen services and used a plated meal delivery system to serve lunch and dinner. The food was loaded into food containers and transported from the central kitchen. Meals were served three times a day: breakfast was delivered from the hours of 07.30–08.30, lunch from 12.00–13.00 and dinner from 18.00–19.00. In the selected hospitals, and in general in Italy, meals at lunch and dinner usually comprise three separate plates called “first”, “second” and “side plate” (contorno in Italian), as well as an additional piece of fruit. The first plate, usually pasta or rice, is seasoned with legumes, vegetables or broth. The second plate consists of cooked meat or fish. The side plate, served on a separate plate, consists of potatoes, legumes or vegetables. The accompanying fruit is usually an apple, orange, pear or peach.15 The main and fundamental difference between these two hospitals is that in the Piedmont hospital, the inpatients chose what to eat the next day from a menu. The dietician passed by the bedside of each inpatient in the morning with a Palmtop, proposing menu alternatives; the patient, based on the diet prescribed by the clinician (who would be notified every morning by fax from the department to the dietetic service), would choose the first plate, second plate, side plate and the fruit. This would occur for both lunch and dinner. Breakfast would be decided by the patient at that moment, and they would choose among coffee, milk, yogurt, tea or chamomile, rusks, biscuits and fruit. In the Campania region, inpatients were given a standard breakfast composed of milk and rusks with jam, but they were able to choose what they wanted for lunch and dinner at the time of the meal. During these mealtimes, they got to choose between two different first plates and two different second plates.

The kitchen of the Campania hospital is located about 10 km from the hospital; therefore, the food is prepared and kept at 65°C for about 2 hours before consumption. Conversely, in the Piedmont hospital, the food is prepared in the kitchen located inside the hospital.

Data Collection

During the study period, we included patients who had been hospitalised for at least three days in obstetrics and gynaecology wards. We excluded non-collaborating patients and those prescribed special diets. The patients were interviewed by two physicians in the Campania hospital and two nurses in the Piedmont hospital, 1–2 days each week on different days. Participants gave their written consent to take part in the study and were informed that all data collected would be analysed and aggregated and that their confidentiality would be strictly protected.

Research ethics committee approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” (prot. N. 405/2018).

Questionnaire

The questionnaire asked respondents to provide the following information:

Sociodemographic data: age (continuous), nationality (Italian, other), education level (primary school, middle school, high school, college degree), marital status (unmarried, married, other) and employment (employed/unemployed).

Expectations: The patients were asked, “How did you expect the quality of food to be before hospitalization?” (answered using a 5-point Likert scale: very poor, poor, sufficient, good, very good).

Characteristics of food served: quality, variety, quantity, presentation (answered using a 5-point Likert scale: very poor, poor, sufficient, good, very good); importance placed on the mealtimes (answered using a 5-point Likert scale: none, little, enough, much, very much).

Characteristics of foodservice: foodservice satisfaction (answered using a 5-point Likert scale: very poor, poor, sufficient, good, very good); courtesy of the staff serving food and trust in the safety of food (answered using a 5-point Likert scale: never, rarely, sometimes, often, always). We also asked whether they brought in food from outside the hospital, from home or from another external catering service (answered using a 5-point Likert scale: never, rarely, sometimes, often, always).

Rate of food waste: To evaluate the amount of food discarded, we used the following question: “In which percentage did you consume your meals?”. This question was asked regarding the first plate, second plate, side plate and fruit (answered using a 5-point Likert scale: nothing/almost nothing, about 1/4, about half, about 3/4, all/almost all). “Almost nothing” means that patients just tasted the food and then refused it.15

Some questions included in the questionnaire were based on the ‘Acute Care Hospital Foodservice Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire ACHFPSQ’16 an instrument used to measure patient satisfaction with a hospital’s foodservice.

Measurement of Food Waste (Wastage Rate)

Starting with the question: “In which percentage did you consume your meals?”, the overall food wasted for each plate was calculated as follows: (percentage of patients who discarded 100% of their food × 1) + (percentage of patients who discarded 75% of their food × 0.75) + (percentage of patients who discarded 50% of their food × 0.50) + (percentage of patients who discarded 25% of their food × 0.25) + (percentage of patients who discarded 0% of their food × 0). The overall amount of food discarded was calculated as the weighted average of the three plates in relation to their average weight, given the first plate was weighted as 1.00; second plate, 0.60; side plate, 0.50; and fruit, 0.40.15 These values were calculated for the three days of food served in the two hospitals.

Sample Size

The sample size was calculated based on the food wasted considering the following assumption: A preliminary observation of food waste in the Campania hospital resulted in about 40%;15 we hypothesized, due to the better organization and different meal delivery system, a smaller amount of food would be wasted in the Piedmont hospital, which would be equal to or less than 28%. Then, assuming an alpha error of 0.05 and a power of 80%, the final sample size was calculated to be about 250 patients for each group.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted for socioeconomics characteristics. The comparison between obstetrics and gynaecology wards of the two hospitals with all the variables of the questionnaire was performed by univariate analysis. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to control for sociodemographic characteristics as potential confounders. Sociodemographic characteristics associated with the outcomes of interest with a p value ≤0.25 were included in the analysis. The Mantel-Haenszel odds ratio and Breslow-Day test for homogeneity of the odds ratios were used to evaluate the correlation between expectation of food quality and the quality of food in these two wards.

Analyses were carried out using the statistical software package SPSS Version 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

During the study period, we collected 550 questionnaires (275 for each hospital). Only 21 inpatients refused to participate: 11 in the Piedmont hospital and 10 in the Campania hospital, with a response rate of 96.2% and 96.5%, respectively.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics

In Table 1, the socio-demographic characteristics of the two groups are reported. The women from Piedmont were older than the women from Campania (34.5% vs 23.3%) and had a higher level of education (80.0% vs 68.7%). In the southern group, there were more housewives/unemployed women (42.9% vs 28.0%), and the number of married women was higher (80.0% vs 58.2%). In both groups, there was a similarly low number of foreign women.

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Participants |

Expectation and Food Quality

The first two questions of the questionnaire asked the patients to judge the quality of food in general and what their expectations about food quality were just before hospitalization. Northern patients had both a better opinion of food quality (54.2% vs 36.0%) and a more positive expectation of food quality (69.5% vs 31.6%). Moreover, more than one-third of southern patients (39.7%) stated to have no expectations compared to 19.6% of northern patients (Table 2). In both hospitals, patients with higher expectations also gave better opinions of food quality (Crude OR = 3.43, C.I. = 2.08–5.64) (Table 3). These results were similar in both hospitals (Mantel-Haenszel OR = 3.22, CI = 1.95–5.35; Homogeneity test p = 0.63).

|

Table 2 Food Quality and Expectation for Food Quality in the Two Hospitals of North and South Italy |

|

Table 3 Food Quality Disaggregated for Expectation in the Two Hospitals of North and South Italy |

Foodservice Characteristics

Northern patients gave a higher judgment concerning variety (56.4 vs 31.3%) and presentation (56.6 vs 26.9%) of food served and were more satisfied with foodservice in general (54.5 vs 38.2%). Conversely, southern patients placed more importance on the hospital mealtimes (72.7 vs 26.2%). Moreover, 30.2% of them (vs only 2.2% of northern) brought food into the hospital from outside, generally from their own homes. Similar opinions have been given regarding courtesy of the staff and beliefs about food safety (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Opinions of Patients Regarding Food Quality and Foodservice |

All these variables have been controlled by multivariate logistic regression analysis for age (<49 vs >50), education level (primary, middle school vs high school, degree), marital status (married vs other) and employment status (employed vs others) as potential confounders. The results, however, were similar to the univariate analysis, except for “variety”, which became more similar in both groups.

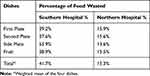

Food Waste

Table 5 shows the percentage of patients who claim to have discarded 50% or more than 50% of each single dish. Therefore, for each dish, more than half of patients from the southern hospital discarded at least 50% of food compared to only about 10% of northern patients.

|

Table 5 Patients Who Claim to Have Discarded 50% or More Than 50% of Each Single Dish |

In Table 6, we compared the two hospitals with respect to the amount of food discarded for each dish and as a total. The southern patients discarded a high amount of food, ranging approximately from 37.6% of the second dish to 53.9% of the side dish. Conversely, the food discarded from northern patients ranged from 13.6% of the side dish to 15.9% of the first dish. Overall southern patients wasted about 41.7% of the food served, and northern patients wasted about 15.3%.

|

Table 6 Food Waste by Single Dish and for the Two Hospitals According to the Patients’ Evaluation (See Methodology for Calculation) |

Discussion

We analysed patient satisfaction with food quality in obstetrics and gynaecology wards of two hospitals, one in Northern Italy and one in Southern Italy. Northern patients were more satisfied with quality of food and foodservice than southern patients.

Patient satisfaction is a multidimensional concept, difficult to measure because it is influenced by a variety of determinants. Therefore, in our study, we tried to deepen the concept of patient satisfaction by introducing the expectations of food quality.

Expectations and their influence on patient satisfaction are a largely debated issue, but the association between the two is inconsistent between studies. Eleven theories on the role of expectation on patient satisfaction have been described, but they were not supported by consistent empirical data.3,17

In our study, there were two significant differences about expectations between the two groups: northern patients had more positive expectations on quality of food, whereas more southern patients stated that they had no expectations.

Moreover, in both hospitals, when the expectations of food quality were higher, the opinions of food quality were higher as well, according to the expectation theories that, in general, explain patient satisfaction as a result of how well a health service fulfils patients’ expectations.18–21

A large difference between the two groups of inpatients concerns the importance placed on the mealtimes and the food brought in from outside. Southern patients gave a great deal of importance to mealtimes, and many of them brought food into the hospital from home through relatives who came to visit them. Understanding the impact of food waste could provide people with motivation to change their attitudes and behaviours.11

We also investigated, as another indicator of care quality, food wasted by patients in the two hospitals. The difference was truly remarkable. Southern patients discarded almost half of food served, whereas northern patients discarded just over 10%. Two reasons can explain this difference: a higher quality of food served and the type of foodservice. In our sample, the best opinions on food quality and foodservice in the North compared to the South were related to less food waste. Moreover, the northern hospital used a bedside menu ordering system, by which the inpatients chose from a menu with many alternatives what to eat the next day, whereas in the southern hospital, the inpatients were able to choose between only two alternatives at the time of the meal.

Studies conducted in other countries are focused mainly on the ways in which food is delivered. The change from standard plate delivery to a bedside menu ordering system reduced food waste from 30% to 26%. The room service system allowed patients to order à la carte meals and receive them within 45 minutes. This model reduced food waste from 29% to 12% compared to the traditional foodservice model.22 Other methods that reduced food waste include bulk food delivery systems in which a variety of food is brought to patients and served from trollies according to each patient’s appetite and choices23 and a two-portion size that allows each patient to choose his or her desired quantity of food in a meal.24

Although limited to only two obstetrics and gynaecology wards, our results are consistent with the differences in healthcare between these two geographical areas.

Northern Italy is more industrialized, healthier and wealthier than Southern Italy. The differences in income between the north and the south are €23.860 and €16.550, respectively.25–28 The National Health Service in Northern Italy is faster, richer and of higher quality, using more modern technologies than in the south.29 Therefore, many patients move from the south to the north in search of better health care. For example, in 2017, the Campania region in the south was classified as having a “great negative balance (-€ 302,1 million)”, as about 10% of their patients moved for care mainly to the Northern region.30

In 2010, a wide investigation conducted by the Ministry of Health in Italy showed that north-west and north-east patients had a higher level of satisfaction with care received in hospital (44.9% and 59.5%, respectively) compared to southern patients (31.3%).31

Moreover, a large study conducted in several hospitals in the Piedmont region, where our northern hospital is located, reported that 31.2% of the food served was wasted.32 However, this last percentage is overestimated compared to our results because it accounts for the food waste along the entire supply chain, not just the food discarded at the bedside. Conversely, a study conducted in three hospitals in Campania, in different wards, reported a percentage of 41.6% of food waste that is consistent with the results of this study.15

Food waste is a worldwide problem due to its economic, social and environmental effects. Especially in hospital food waste could have a negative impact on the overall patient satisfaction.

In general, and compared to other national and international experiences, the amount of food waste in the southern hospital was very high and not acceptable considering that it concerns only one element of the food chain. At least two other elements of this chain should be added: during production and after delivery, as patients could choose between two options at mealtime and many of the second meal options were automatically discarded. Therefore, we can imagine a food waste of much more than 50%.

As a result of these findings, we communicated to the management of the southern hospital the amount of food waste, suggesting to improve the main failures of the food served: quality, presentation and variety. Furthermore, the delivery organization should be changed in such a way that a system is used which reduces the amount of unused food.

The study has several limitations. As already stated, the comparison between one hospital in Northern Italy and one hospital in Southern Italy was limited to only the obstetrics and gynaecology wards; therefore, it is difficult to make general considerations on these two geographical. In addition, these two hospitals had a different type of kitchen that supplied them, kitchen located inside for the northern hospital and kitchen located about 10 km away for the southern one. This difference might have affected the taste and texture of the southern hospital food.

There were different interviewers in the two hospitals (nurses in the north and physicians in the south), and a reporting bias could be possible because participants could give answers in the sense of social desirability. For example, the high number of ‘no expectations’ in the south could be due to a lower insistence on this specific question by southern interviewers. The responders were all female and of only one medical specialization, whose opinion could be different from male patients or from other types of patients. The question about expectations was placed after, not before, the consumption of food, so the answers might have been distorted by this experience.

The methodology used to calculate the food wasted in these facilities is innovative: we invited the patients to declare the amount of food they had discarded themselves.15 This method needs to be confirmed with further studies and to be compared with other, more validated methodologies.

Acknowledgment

The costs of the open access publication were supported by the “Programma Valere 2019” of the University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” (Naples, Italy)”.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Prakash B. Patient satisfaction. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3(3):151–155. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.74491

2. Busse R. Improving Healthcare Quality in Europe: Characteristics, Effectiveness and Implementation of Different Strategies. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2019.

3. Batbaatar E, Dorjdagva J, Luvsannyam A, Savino MM, Amenta P. Determinants of patient satisfaction: a systematic review. Perspect Public Health. 2017;137(2):89–101. doi:10.1177/1757913916634136

4. Kravitz RL. Measuring patients’ expectations and requests. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(9 Pt 2):881–888. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-134-9_part_2-200105011-00012

5. Dall’Oglio I, Nicolò R, Di Ciommo V, et al. A systematic review of hospital foodservice patient satisfaction studies. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(4):567–584. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2014.11.013

6. Caldeira C, Corrado S, Serenella S. Food Waste Accounting: Methodologies, Challenges and Opportunities. Challenges and Opportunities. Publications Office; 2017.

7. FAO. Food wastage footprint. Impacts on natural resources. Available from: http://www.fao.org/3/i3347e/i3347e.pdf.

8. United Nations. Goal 12: ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns. Available from: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/.

9. Gustavsson J. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention; Study Conducted for the International Congress Save Food! at Interpack 2011, Düsseldorf, Germany. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2011.

10. Chalak A, Abou-Daher C, Chaaban J, Abiad MG. The global economic and regulatory determinants of household food waste generation: a cross-country analysis. Waste Manag. 2016;48:418–422. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2015.11.040

11. Ishangulyyev R, Kim S, Lee SH. Understanding food loss and waste-why are we losing and wasting food? Foods. 2019;8(8):297. doi:10.3390/foods8080297

12. Italian Government. Gazzetta Ufficiale. Legge 19 agosto 2016, n. 166. Disposizioni concernenti la donazione e la distribuzione di prodotti alimentari e farmaceutici a fini di solidarietà sociale e per la limitazione degli sprechi. Available from: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2016/08/30/16G00179/sg.

13. Italian Government. Ministero della Salute. SPAIC - Cause dello spreco alimentare ed interventi correttivi. Available from: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2566_allegato.pdf.

14. Italian Government. Ministero della Salute. Linee di indirizzo rivolte agli enti gestori di mense scolastiche, aziendali, ospedaliere, sociali e di comunità, al fine di prevenire e ridurre lo spreco connesso alla somministrazione degli alimenti. Available from: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2748_allegato.pdf.

15. Schiavone S, Pelullo CP, Attena F. Patient evaluation of food waste in three hospitals in Southern Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22):4330. doi:10.3390/ijerph16224330

16. Capra S, Wright O, Sardie M, Bauer J, Askew D. The acute hospital foodservice patient satisfaction questionnaire: the development of a valid and reliable tool to measure patient satisfaction with acute care hospital foodservices. Foodservice Res Int. 2005;16(1–2):1–14. doi:10.1111/J.1745-4506.2005.00006.X

17. Batbaatar E, Dorjdagva J, Luvsannyam A, Amenta P. Conceptualisation of patient satisfaction: a systematic narrative literature review. Perspect Public Health. 2015;135(5):243–250. doi:10.1177/1757913915594196

18. Crow R, Gage H, Hampson S, et al. The measurement of satisfaction with healthcare: implications for practice from a systematic review of the literature. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6(32):1–244. doi:10.3310/hta6320

19. Curtice J, Heath O. Does choice deliver? Public satisfaction with the health service. Polit Stud. 2012;60(3):484–503. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00976.x

20. Hills R, Kitchen S. Toward a theory of patient satisfaction with physiotherapy: exploring the concept of satisfaction. Physiother Theory Pract. 2007;23(5):243–254. doi:10.1080/09593980701209394

21. Staniszewska S, Ahmed L. The concepts of expectation and satisfaction: do they capture the way patients evaluate their care? J Adv Nurs. 1999;29(2):364–372. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00897.x

22. McCray S, Maunder K, Krikowa R, MacKenzie-Shalders K. Room service improves nutritional intake and increases patient satisfaction while decreasing food waste and cost. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(2):284–293. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2017.05.014

23. Hartwell HJ, Edwards JSA, Beavis J. Plate versus bulk trolley food service in a hospital: comparison of patients’ satisfaction. Nutrition. 2007;23(3):211–218. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2006.12.005

24. Dias-Ferreira C, Santos T, Oliveira V. Hospital food waste and environmental and economic indicators – a Portuguese case study. Waste Manag. 2015;46:146–154. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2015.09.025

25. Coviello V, Buzzoni C, Fusco M, et al. La sopravvivenza dei pazienti oncologici in Italia. Epidemiol Prev. 2017;41(2 Suppl 1):1–244. doi:10.19191/EP17.2S1.P001.017

26. Dallolio L, Lenzi J, Fantini MP. Temporal and geographical trends in infant, neonatal and post-neonatal mortality in Italy between 1991 and 2009. Ital J Pediatr. 2013;39:19. doi:10.1186/1824-7288-39-19

27. Petrelli A, Di Napoli A, Sebastiani G, et al. Atlante italiano delle disuguaglianze di mortalità per livello di istruzione. Epidemiol Prev. 2019;43(1S1):1–120. doi:10.19191/EP19.1.S1.002

28. Simeoni S, Frova L, de Curtis M. Inequalities in infant mortality in Italy. Ital J Pediatr. 2019;45(1):11. doi:10.1186/s13052-018-0594-6

29. OECD. Targeted action needed to reduce the high level of variation in health care that persists across Italy. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/italy/Geographic-Variations-in-Health-Care_Italy.pdf.

30. Report Osservatorio GIMBE. La mobilità sanitaria interregionale nel 2017. Available from: http://www.quotidianosanita.it/allegati/allegato2014526.pdf.

31. Italian Government. Ministero della Salute. Linee di indirizzo nazionali per la riabilitazione nutrizionale nei disturbi dell’alimentazione. http://www.quadernidellasalute.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_1702_allegato.pdf.

32. Regione Piemonte. Progetto di valutazione degli scarti dei pasti. Available from: https://www.regione.piemonte.it/sanita/cms2/documentazione/category/152-rete-dietistica-e-nutrizione-clinica?start=20.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.