Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 14

Parent-Adolescent Communication Quality and Life Satisfaction: The Mediating Roles of Autonomy and Future Orientation

Received 15 May 2021

Accepted for publication 1 July 2021

Published 21 July 2021 Volume 2021:14 Pages 1091—1099

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S317389

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Mei-Chun Cheung

Xinwen Bi, Shuqiong Wang

Department of Education, Shandong Women’s University, Jinan, Shandong Province, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Shuqiong Wang

Department of Education, Shandong Women’s University, Jinan, Shandong Province, People’s Republic of China

Tel +86-18653143970

Email [email protected]

Background: Previous studies have suggested that family communication quality is an important factor that can influence adolescents’ life satisfaction. However, relatively few studies have examined this relationship in the Chinese cultural context or explored the potential mechanisms underlying this relationship. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate whether family communication quality is closely linked to Chinese adolescents’ life satisfaction and whether this link was mediated by autonomy and future orientation.

Methods: This study recruited 442 Chinese college students (67.19% girls) as participants. Based on a longitudinal design, the participants reported family communication quality at Time 1 and reported autonomy, future orientation, and life satisfaction at Time 2.

Results: The results of correlation analysis showed the existence of a positive correlation between family communication quality, autonomy, future orientation, and life satisfaction. The mediation models showed family communication quality predicted adolescents’ life satisfaction through the mediating effects of autonomy and future orientation. Furthermore, autonomy and future orientation not only independently mediated the relationship between family communication quality and life satisfaction but sequentially mediated this relationship.

Conclusion: Autonomy and future orientation mediated the relationship between family communication quality and life satisfaction. The findings of the present study highlight the significance of elevating family communication quality and promoting adolescents’ development of autonomy and future orientation to enhance their life satisfaction.

Keywords: family communication, life satisfaction, autonomy, future orientation, adolescence

Introduction

With the development of positive psychology, researchers have paid much attention to life satisfaction and actively studied this research area from clinical, developmental, and neuroscientific perspectives.1–3 Life satisfaction is defined as individuals’ subjective evaluation of the quality of their lives.4 Numerous empirical studies have found that individuals’ higher level of satisfaction with life is beneficial for their development in multiple domains, such as keeping in good health,5 having more adaptive coping behaviors and fewer problem behaviors,6,7 and attaining educational and occupational success.8,9 Given the beneficial role of life satisfaction, it is critical to investigate the influential factors of life satisfaction and explore the underlying mechanisms. The present study focused on the effect of parent-adolescent communication quality on adolescents’ life satisfaction. As an extension of previous research, we further investigated the mediating effects of autonomy and future orientation on this relationship.

Parent-Adolescent Communication Quality and Life Satisfaction

As a pivotal factor in the family system, family communication plays an important role in affecting children’s development.10 Especially in the period of adolescence, family communication becomes more critical because parents and adolescents need to adapt to the rapid development of adolescents’ psychology and renegotiate their power boundaries.11 The quality of communication between parents and adolescents can influence multiple domains of adolescent developmental outcomes, including life satisfaction. Previous research has found that adolescents would perceive more life satisfaction when they communicate openly with parents, whereas adolescents were less likely to perceive satisfaction with life when they encounter obstacles in the process of communicating with parents.12–14 Furthermore, the positive relationship between parent-adolescent communication quality and life satisfaction remains significant even after controlling for other factors, such as perceived schoolwork pressure and bullying victimization.15 Open communication between parents and adolescents may create a positive family atmosphere and facilitate the operation of family function, which may promote adolescents’ satisfaction with life. In contrast, problems in family communication (eg, the hesitation to disclose personal feelings and avoidance of talking about some topics) may lead to misunderstandings and conflicts between parents and adolescents, which may decrease adolescents’ life satisfaction.

The findings of previous research suggest that the positive effect of family communication quality on life satisfaction is well established; however, the mechanisms underlying this relationship have not been adequately studied. Although some research has examined the mediating factors among this relationship, including emotional intelligence,16 self-esteem, classroom environment, and feelings of loneliness,13 it is still far from comprehensively understanding how parent-adolescent communication quality is associated with adolescents’ life satisfaction. The current study focused on examining the mediating roles of autonomy and future orientation to unravel the mechanisms underlying this relationship in the Chinese cultural context.

Mediating Effect of Autonomy

According to the findings of empirical studies and self-determination theory (SDT), autonomy may be a promising mediator between family communication quality and adolescents’ life satisfaction. Autonomy means regulation by the self, rather than by external forces.17 The development of adolescents’ autonomy is influenced by multiple familial factors, such as parenting styles,18 parenting practices,19 and parental beliefs.20 In addition to these factors, researchers also have explored the influence of family communication quality on autonomy and found that high quality of family communication (eg, more open communication and fewer problems in the communication) is conducive to the satisfaction of autonomy.21 Open communication creates a positive family environment in which adolescents have more opportunities to develop their autonomy, such as freely expressing feelings and perspectives, independently making decisions, and engaging in autonomous behaviors instead of being influenced by external forces.

In turn, adolescents’ development of autonomy plays an influential role in life satisfaction. SDT provides a framework for understanding this relationship. According to SDT, the satisfaction of the psychological needs for autonomy is critical for individuals’ optimal functioning and well-being.22 Empirical evidence supported this theory and indicated that adolescents’ perception of autonomy is positively associated with life satisfaction.23,24 When adolescents achieve adequate autonomy, their psychological need for autonomy can be fulfilled, which results in a higher level of life satisfaction.

Mediating Effect of Future Orientation

Another possible mediator between parent-adolescent communication quality and life satisfaction is adolescents’ future orientation. Future orientation is defined as consciously representing and self-constructing images of the future.25 Theoretical and empirical evidence indicate that communication quality between parents and adolescents is closely associated with adolescents’ future orientation. According to evolutionary life history theory, individuals in positive developmental environments (eg, supportive interpersonal relations and high quality of family communication) are more likely to adopt long-term strategies and orient towards the future. In contrast, those in negative developmental environments (eg, unsafe environments and negative family interactions) tend to discount the importance of future orientation and adopt short-term strategies.26 As one of the most important interpersonal interactions, communication between parents and adolescents creates a developmental environment that plays a vital role in affecting adolescents’ future orientation. Empirical research supported this theory and found that open communication with parents promoted individuals to endorse future time perspective, whereas problematic family communication hindered them from developing future time perspective.27

Adolescents’ future orientation, in turn, can impact their perception of life satisfaction. Generally, individuals’ orientation towards the future promoted them to perceive higher levels of life satisfaction. And this relationship was discovered in various samples, including samples from both Western28–30 and Eastern cultural backgrounds.31,32 When individuals envision and plan for the future, take actions to pursue future goals, and anticipate the consequence of their actions, they may have feelings of control over their lives. And life satisfaction may generate from these feelings.33,34

Autonomy and Future Orientation

Based on theoretical and empirical evidence mentioned above, we hypothesized that autonomy and future orientation independently mediated the relationship between family communication quality and life satisfaction. Besides, we expected that autonomy and future orientation would sequentially mediate this relationship. Previous research has found that autonomy was positively related to future orientation.35 The development of adolescents’ future orientation requires the opportunity to explore their interests, values, and goals, and the freedom to make choices. When adolescents achieve adequate autonomy, they can plan for the future, devote themselves to achieving their future goals, and weigh the future paths based on their interests and values instead of social pressures or external expectations. In other words, adolescents’ autonomy may be a psychological resource that is beneficial for the development of future orientation. Considering the relationships between these variables mentioned above, we hypothesized that family communication quality may influence adolescents’ achievement of autonomy, which may affect the development of future orientation and in turn, contributes to adolescents’ life satisfaction.

The Chinese Cultural Context

Although theories and empirical evidence have confirmed the close relationships between family communication quality, autonomy, future orientation, and life satisfaction, previous research was mainly conducted in Western cultural contexts. There are some unique characteristics of traditional Chinese culture which may influence the effects of family communication quality and autonomy. For instance, traditional Chinese culture emphasizes nonconfrontational and implicit communication, encourages submission to authority, and devalues autonomy.21,36,37 However, with the social change, Chinese culture is changing towards individualism which emphasizes autonomy and the self and discourages reserved communication style.38,39 Previous research has indicated that broad cultural backgrounds may influence the effects of parent-adolescent interactions on adolescents’ developmental outcomes.40,41 Therefore, the contemporary Chinese cultural context may provide a unique milieu to examine the relationships between family communication quality, autonomy, future orientation, and life satisfaction. We intended to investigate whether the relationships between these variables in the Chinese cultural context would be different from those in Western cultural contexts because of the influence of traditional Chinese culture or similar to those in Western cultural contexts because of the influence of individualism.

Objective

The overall purpose of this study was to examine the relationships between parent-adolescent communication quality and life satisfaction and to explore the inner mechanism among Chinese adolescents by using a longitudinal design. Specifically, the first aim of this study was to investigate whether parent-adolescent communication quality is associated with adolescents’ life satisfaction in the Chinese cultural background. The second aim of this study was to examine the mediating effects of autonomy and future orientation on the relationship between parent-adolescent communication quality and life satisfaction. In the mediation model, we tried to explore the independent and sequential mediating effects of autonomy and future orientation.

Based on self-determination theory, evolutionary life history theory, and empirical evidence, we proposed two specific hypotheses. First, high quality of parent-adolescent communication (eg, more open communication and fewer problems in communication) would elevate adolescents’ life satisfaction in the contemporary Chinese cultural context. Second, adolescents’ autonomy and future orientation would independently and sequentially mediate the relationship between parent-adolescent communication quality and life satisfaction.

Method

Participants

The present study used a one-year longitudinal design to collect data. The open-source statistical language R was used to determine the minimum size of the research sample with power = 0.80 options. The result showed that the minimum sample size was determined to be 127. By using cluster sampling, 550 adolescents were recruited from 2 colleges in the urban areas of Jinan, the capital city of Shandong Province in China (65.01% girls; age range: 16.10–24.09 years; Mage = 18.97 ± 0.89 years). At Time 2, 108 students either withdrew from the study or did not complete the questionnaires. Finally, 442 college students who accomplished two-wave assessments were retained in the data set (67.19% girls). In the final data set, the educational accomplishment of mothers and fathers, respectively, were as follows: 61.54% and 50.00% had completed junior high school or less, 29.86% and 37.78% got senior high school degree, and 7.92% and 11.54% were college graduates. For the parents’ occupational statuses, 48.42% of mothers and 29.64% of fathers were peasant or jobless, and 50.22% of mothers and 68.55% of fathers had professional or semiprofessional occupations.

Procedure

Before collecting data, participants were informed about the purposes and procedures of this study. Then, all participants completed written informed consent, which acknowledged that they understood and agreed to the terms of this study, including its voluntary and confidential nature. The participants’ parents also provided informed consent for their child to participate. During the process of collecting data, the participants rated their communication quality with parents at Time 1, and they rated autonomy, future orientation, and life satisfaction at Time 2. At each time point, the participants were instructed to complete self-reported questionnaires in classrooms. It took about 30 minutes to complete the questionnaires. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received ethical approval from the ethics review board of Shandong Women’s University.

Measures

Family Communication Quality

The Parent-Adolescent Communication Scale was used to measure youths’ perceptions of communication quality with their mothers and fathers, respectively.42 This measure consists of two subscales. The open family communication subscale measures the perception of freely exchanging information and opinions in the process of communicating with parents (10 items; eg, “I find it easy to discuss problems with my mother/father”). The problems in the family communication subscale measures obstacles in parent-adolescent communication, such as the negative feelings in communicating with parents and the reluctance to disclose opinions and feelings (10 items; eg, “I am sometimes afraid to ask my mother/father for what I want”). The items were rated by adolescents on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). To generate a latent construct, the responses of items in the problems in the family communication subscale were reverse-coded.43 Higher scores indicate that there are fewer problems in parent-adolescent communication. In the present study, the total scale had good reliability (father: α = 0.87; mother: α = 0.87). Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) indicated that the items fitted well to the two-factor model for both parents (father: RMSEA = 0.051, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92; mother: RMSEA = 0.052, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91).

Autonomy

The Worthington Autonomy Scale (WAS) was used to assess autonomy.44 Three dimensions of this scale were used in the present study: the behavioral autonomy (10 items; eg, “I apologize for my part of an argument even if the other person doesn’t”), the emotional autonomy (10 items; eg, “I can be close to someone and give them space at the same time”), and the value autonomy (10 items; eg, “I would hold to my religious beliefs even if my family and friends did not approve”). Participants reported their endorsement of each item on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicated higher levels of autonomy. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.80 for this scale. The results of CFA showed that the present data fitted well to the structure of this scale (RMSEA = 0.065, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.92).

Future Orientation

Future orientation was assessed by the Chinese version of Questionnaire for Teenagers’ Future Orientation which was partly derived from the future temporal perspective subscale of Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Inventory.45,46 This scale measures the extension of future orientation (3 items; eg, “I can imagine my life in ten years”), the density of future-oriented thoughts (6 items; eg, “I often think about my future”), optimistic beliefs about future (5 items; eg, “I believe I have the ability to create a better future”), planning for the future (12 items; eg, “I believe that a person’s day should be planned ahead each morning”) and taking action to achieve future goals (5 items; eg, “I am able to resist temptations when I know that there is work to be done”). Participants assessed the items on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (completely false) to 5 (completely true). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.91 in the current study. CFA indicated that the present data fitted well to the structure of this scale (RMSEA = 0.054, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91).

Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction was assessed by the Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (MSLSS).47 The Chinese version of this scale was developed and eventually, a 36-item version was produced (Zhang et al, 2004).48 This scale measures the satisfaction with specific domains of life, such as family, friends, study, freedom, school, and living environment. Participants responded to each item on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (completely false) to 7 (completely true). In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.93 for this scale. As indicated by CFA, the present data fitted the six-factor structure well (RMSEA = 0.053, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.90).

Analysis Plan

In the present study, SPSS 22.0 was used to conduct descriptive statistics among the variables. Mplus 7.4 was used to perform structural equation modeling.49 In the total effect model, the relations between parent-adolescent communication quality and adolescents’ life satisfaction was examined. In the mediation model, the independent and sequential mediating effects of autonomy and future orientation on this relationship were examined. All these variables were modeled as latent variables based on the dimensions of each scale (see Figure 1).Overall model fit was acceptable when root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08, comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.90, and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) > 0.90.50 The significance of direct and indirect effects was tested using 95% bias-corrected bootstrap. A 95% confidence interval (95% CI) that excluded zero indicated significant effect. Missing values were replaced with the series mean method in SPSS 22.0.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

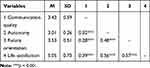

The values of mean, standard deviation, and correlation among parent-adolescent communication quality, autonomy, future orientation, and life satisfaction are presented in Table 1. Parent-adolescent communication quality was positively associated with autonomy, future orientation, and life satisfaction. Autonomy and future orientation were positively correlated with life satisfaction, and they were also positively linked to each other.

|

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics of the Variables |

Mediating Effect of Autonomy and Future Orientation

The fitting indexes of the total effect model were acceptable (RMSEA = 0.075, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96). The total effect of parent-adolescent communication quality on life satisfaction was positive (β = 0.51, 95% CI [0.40, 0.61]). Then we examined the indirect effects of parent-adolescent communication quality on adolescents’ life satisfaction through the mediation of autonomy and future orientation by using bias-corrected bootstrapping. The fitting indexes of the mediation model also were acceptable (RMSEA = 0.073, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.92). As displayed in Table 2, the total indirect effect of parent-adolescent communication quality on adolescents’ life satisfaction was significant. Specifically, autonomy and future orientation independently mediated the relationship between parent-adolescent communication quality and life satisfaction. In addition, autonomy and future orientation also sequentially mediated this relationship.

|

Table 2 Standardized Estimates and 95% CIs for Direct and Indirect Effects |

As shown in Figure 1, parent-adolescent communication quality positively predicted adolescents’ autonomy (β = 0.44, 95% CI [0.34, 0.53]) and future orientation (β = 0.17, 95% CI [0.04, 0.29]). In turn, adolescents’ autonomy and future orientation positively predicted life satisfaction (autonomy: β = 0.42, 95% CI [0.29, 0.57]; future orientation: β = 0.40, 95% CI [0.24, 0.55]). Besides, adolescents’ autonomy was positively linked to future orientation (β = 0.52, 95% CI [0.40, 0.64]).

Discussion

The present study aimed to examine whether parent-adolescent communication quality was associated with adolescents’ life satisfaction in the contemporary Chinese cultural context and what were the underlying mechanisms in this relationship. We used a longitudinal research design to unravel the link between parent-adolescent communication quality and adolescents’ life satisfaction and to examine the mediating roles of autonomy and future orientation in the link.

Parent-Adolescent Communication Quality and Life Satisfaction

Consistent with previous research,12–14 our findings indicated that high quality of family communication enhanced adolescents’ life satisfaction. This may be explained by the fact that adolescents who openly communicate with parents and have fewer problems in communication with parents are more likely to perceive parental support, trust, and closeness. In this process, adolescents’ psychological need for relatedness would be fulfilled, and family function would be smoothly implemented.10 Therefore, high quality of family communication may be conducive to the achievement of life satisfaction.10,13,51 Although traditional Chinese culture encourages nonconfrontational and implicit communication,21,37 contemporary Chinese culture places more importance on freedom in expression because of the influence of individualism.38 In this situation, open communication matches with the broad cultural context and plays a positive role in promoting adolescents’ well-being.

Mediation of Autonomy and Future Orientation

The present study found that autonomy independently mediated the relationship between family communication quality and adolescents’ life satisfaction. High quality of family communication was a supportive family resource that can help adolescents to develop autonomy.21 In the process of openly communicating with parents, adolescents have more opportunities to express themselves and make decisions according to their own volition rather than external forces. In turn, the acquisition of autonomy promoted adolescents to perceive life satisfaction.23,24 This finding is concordant with previous studies and provides empirical verification for self-determination theory which proposes that the fulfillment of adolescents’ basic psychological need for autonomy promotes their optimal development, including the achievement of life satisfaction.22 More importantly, this study extends previous findings to the Chinese cultural context. Traditional Chinese culture emphasizes conformity to norms and authority.36 With the social change, Chinese culture is exchanging, fusing, and colliding with Western cultures and contemporary Chinese culture is changing towards individualism.39 Contemporary Chinese adolescents tend to place more value on acquiring autonomy, which results in the positive effects of autonomy on their life satisfaction.

In addition to autonomy, future orientation also independently mediated the relationship between family communication quality and adolescents’ life satisfaction. This result was consistent with previous research and supported evolutionary life history theory. According to this theory, high quality of family communication provides adolescents with a positive developmental environment which promotes them to adopt long-term strategies and orient towards the future.26 Adolescents who experience a high quality of communication with parents would perceive more support from parents; then they would devote more time to envisioning and exploring the future instead of dealing with negative interactions with parents in the present.27 In turn, future-oriented adolescents would achieve more gratification from planning for the future and performing goal-oriented tasks, which leads to a high level of life satisfaction.30,52,53

The present study also found that family communication quality could account for Chinese adolescents’ life satisfaction through the sequential mediating effect of autonomy and future orientation. In other words, Chinese adolescents who experience a high quality of family communication are more likely to have adequate autonomy, which may contribute to the development of future orientation and in turn, result in higher levels of life satisfaction. This finding may be due to that adolescents’ development of future orientation needs adequate autonomy.35 When adolescents achieve adequate autonomy (eg, making decisions volitionally and taking autonomous actions), they would have more opportunities to orient towards the future (eg, exploring the possibilities of the future).

Contributions and Limitations

There are some important contributions of this study. First, by using a longitudinal design, the present study enriches the literature on the relationships between family communication quality and life satisfaction among Chinese adolescents. Second, the findings extend our insights into the underlying mechanism of this relationship by demonstrating that in addition to the mediators discovered in previous research (eg, emotional intelligence, self-esteem, classroom environment, and feelings of loneliness), adolescents’ autonomy and future orientation can play important mediating roles in the links between family communication quality and adolescents’ life satisfaction. Furthermore, by including both mediators in the model, the current study examined the independent and sequential mediating effects of these mediators. Third, these findings may provide practical implications for how to enhance adolescents’ life satisfaction. For instance, parents should communicate openly with their children and create positive family environment. In addition, parents should adopt effective strategies to promote adolescents’ development of autonomy and future orientation, which may contribute to adolescents’ well-being. Additionally, psychologist professionals also should commit to increasing adolescents’ life satisfaction, such as providing interventions for families with communication problems, guiding parents to fulfill adolescents’ psychological need for autonomy, and developing programs to direct adolescents towards their future.

Despite the above-mentioned contributions, some limitations of this study should be mentioned. First, this study was conducted among Chinese college students in urban areas, which limits the generalization of the findings to other age groups or cultural contexts. Second, we used the self-reporting method to collect data, which may increase the risk of common method bias. Future research should use multiple appraisal methods to reduce such bias. Third, this study found that the relationship between family communication quality and Chinese adolescents’ life satisfaction was partially mediated, suggesting that a further understanding of this relationship requires information on other mediators.

Conclusions

The present study makes the first attempt to simultaneously examine the mediating effects of autonomy and future orientation in one study to unravel the association between family communication quality and life satisfaction and provides support for self-determination theory and evolutionary life history theory. Results indicated that high quality of family communication is conducive to adolescents’ life satisfaction in the contemporary Chinese cultural context. In addition, adolescents’ autonomy and future orientation can independently and sequentially mediate the relationship between family communication quality and adolescents’ life satisfaction. The findings of this study highlight the importance of enhancing the quality of family communication and promoting the development of adolescents’ autonomy and future orientation to increase adolescents’ life satisfaction.

Funding

This study was funded by the Scientific Research Fund for High-level Talents in Shandong Women’s University (2019RCYJ05) awarded to Xinwen Bi.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Chaves C, Hervas G, García FE, Vazquez C. Building life satisfaction through well-being dimensions: a longitudinal study in children with a life-threatening illness. J Happiness Stud. 2016;17(3):1051–1067. doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9631-y

2. Willroth EC, Atherton OE, Robins RW. Life satisfaction trajectories during adolescence and the transition to young adulthood: findings from a longitudinal study of Mexican-origin youth. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2020;120(1):192–205. doi:10.1037/pspp0000294

3. Zhu X, Wang K, Chen L, et al. Together means more happiness: relationship status moderates the association between brain structure and life satisfaction. Neuroscience. 2018;384:406–416. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.05.018

4. Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL. Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychol Bull. 1999;125(2):276–302. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

5. Siahpush M, Spittal M, Singh GK. Happiness and life satisfaction prospectively predict self-rated health, physical health, and the presence of limiting, long-term health conditions. Am J Health Promot. 2008;23(1):18–26. doi:10.4278/ajhp.061023137

6. Jiang X, Fang L, Lyons MD. Is life satisfaction an antecedent to coping behaviors for adolescents? J Youth Adolesc. 2019;48(11):2292–2306. doi:10.1007/s10964-019-01136-6

7. Jung S, Choi E. Life satisfaction and delinquent behaviors among Korean adolescents. Pers Individ Differ. 2017;104:104–110. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.07.039

8. Chughtai AA. A closer look at the relationship between life satisfaction and job performance. Appl Res Qual Life. 2021;16(2):805–825. doi:10.1007/s11482-019-09793-2

9. Heffner AL, Antaramian SP. The role of life satisfaction in predicting student engagement and achievement. J Happiness Stud. 2016;17(4):1681–1701. doi:10.1007/s10902-015-9665-1

10. Olson DH. Circumplex model of marital and family systems. J Fam Ther. 2000;22(2):144–167. doi:10.1111/1467-6427.00144

11. Steinberg L. Adolescence.

12. Baxter LA, Pederson JR. Perceived and ideal family communication patterns and family satisfaction for parents and their college-aged children. J Fam Commun. 2013;13(2):132–149. doi:10.1080/15267431.2013.768250

13. Cava M-J, Buelga S, Musitu Ochoa G. Parental communication and life satisfaction in adolescence. Span J Psychol. 2014;17:1–8. doi:10.1017/sjp.2014.107

14. Levin KA, Dallago L, Currie C. The association between adolescent life satisfaction, family structure, family affluence and gender differences in parent-child communication. Soc Indic Res. 2012;106(2):287–305. doi:10.1007/s11205-011-9804-y

15. De Looze ME, Cosma AP, Vollebergh WAM, et al. Trends over time in adolescent emotional wellbeing in the Netherlands, 2005–2017: links with perceived schoolwork pressure, parent-adolescent communication and bullying victimization. J Youth Adolesc. 2020;49(10):2124–2135. doi:10.1007/s10964-020-01280-4

16. Szcześniak M, Tułecka M. Family functioning and life satisfaction: the mediatory role of emotional intelligence. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13:223–232. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S240898

17. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self‐regulation and the problem of human autonomy: does psychology need choice, self‐determination, and will? J Pers. 2006;74(6):1557–1586. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00420.x

18. Bi X, Yang Y, Li H, Wang M, Zhang W, Deater-Deckard K. Parenting styles and parent-adolescent relationships: the mediating roles of behavioral autonomy and parental authority. Front Psychol. 2018;9. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02187

19. Ravindran N, Hu Y, McElwain NL, Telzer EH. Dynamics of mother-adolescent and father-adolescent autonomy and control during a conflict discussion task. J Fam Psychol. 2020;34(3):312–321. doi:10.1037/fam0000588

20. Roche KM, Caughy MO, Schuster MA, Bogart LM, Dittus PJ, Franzini L. Cultural orientations, parental beliefs and practices, and Latino adolescents’ autonomy and independence. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43(8):1389–1403. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9977-6

21. Liu Q, Lin Y, Zhou Z, Zhang W. Perceived parent-adolescent communication and pathological Internet use among Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. J Child Fam Stud. 2019;28(6):1571–1580. doi:10.1007/s10826-019-01376-x

22. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

23. Ng W. Processes underlying links to subjective well-being: material concerns, autonomy, and personality. J Happiness Stud. 2015;16(6):1575–1591. doi:10.1007/s10902-014-9580-x

24. Olesen MH, Thomsen DK, O’Toole MS. Subjective well-being: above neuroticism and extraversion, autonomy motivation matters. Pers Individ Differ. 2015;77:45–49. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.033

25. Seginer R. Future Orientation: Developmental and Ecological Perspectives. New York: Springer; 2009.

26. Kruger DJ, Reischl T, Zimmerman MA. Time perspective as a mechanism for functional developmental adaptation. J Soc Evol Cult Psychol. 2008;2(1):1–22. doi:10.1037/h0099336

27. Zambianchi M, Ricci Bitti PE. The role of proactive coping strategies, time perspective, perceived efficacy on affect regulation, divergent thinking and family communication in promoting social well-being in emerging adulthood. Soc Indic Res. 2014;116(2):493–507. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0307-x

28. Azizli N, Atkinson BE, Baughman HM, Giammarco EA. Relationships between general self-efficacy, planning for the future, and life satisfaction. Pers Individ Differ. 2015;82:58–60. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.006

29. Cabras C, Mondo M. Future orientation as a mediator between career adaptability and life satisfaction in university students. J Career Dev. 2018;45(6):597–609. doi:10.1177/0894845317727616

30. Zhang JW, Howell RT. Do time perspectives predict unique variance in life satisfaction beyond personality traits? Pers Individ Differ. 2011;50(8):1261–1266. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.02.021

31. Dwivedi A, Rastogi R. Proactive coping, time perspective and life satisfaction: a study on emerging adulthood. J Health Manag. 2017;19(2):264–274. doi:10.1177/0972063417699689

32. Su S, Li X, Lin D, Zhu M. Future orientation, social support, and psychological adjustment among left-behind children in rural China: a longitudinal study. Front Psychol. 2017;8. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01309

33. Hong Y, Liu L, Lin R, Lian R. The relationship between perceived control and life satisfaction in Chinese undergraduates: the mediating role of envy and moderating role of self-esteem. Curr Psychol. 2020;1–9. doi:10.1007/s12144-020-00863-5

34. Kiral Ucar G, Hasta D, Kaynak Malatyali M. The mediating role of perceived control and hopelessness in the relation between personal belief in a just world and life satisfaction. Pers Individ Differ. 2019;143:68–73. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2019.02.021

35. Akirmak U, Tuncer N, Akdogan M, Erkat OB. The associations of basic psychological needs and autonomous-related self with time perspective: the cultural and familial antecedents of balanced time perspective. Pers Individ Differ. 2019;139:90–95. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.008

36. Chuang SS, Glozman J, Green DS, Rasmi S. Parenting and family relationships in Chinese families: a critical ecological approach. J Fam Theory Rev. 2018;10(2):367–383. doi:10.1111/jftr.12257

37. Fang T, Faure GO. Chinese communication characteristics: a Yin Yang perspective. Int J Intercult Relat. 2011;35(3):320–333. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.06.005

38. Xu Y, Hamamura T. Folk beliefs of cultural changes in China. Front Psychol. 2014;5. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01066

39. Zeng R, Greenfield PM. Cultural evolution over the last 40 years in China: using the Google Ngram viewer to study implications of social and political change for cultural values. Int J Psychol. 2015;50(1):47–55. doi:10.1002/ijop.12125

40. Bi X, Zhang L, Yang Y, Zhang W. Parenting practices, family obligation, and adolescents’ academic adjustment: cohort differences with social change in China. J Res Adolesc. 2020;30(3):721–734. doi:10.1111/jora.12555

41. Lansford JE, Godwin J, Al-Hassan SM, et al. Longitudinal associations between parenting and youth adjustment in twelve cultural groups: cultural normativeness of parenting as a moderator. Dev Psychol. 2018;54(2):362–377. doi:10.1037/dev0000416

42. Barnes H, Olson DH. Parent-Adolescent Communication Scale. Minneapolis: Life Innovations Inc; 2003.

43. Simpson EG, Lincoln CR, Ohannessian CM. Does adolescent anxiety moderate the relationship between adolescent-parent communication and adolescent coping? J Child Fam Stud. 2020;29(1):237–249. doi:10.1007/s10826-019-01572-9

44. Anderson RA, Worthington L, Anderson WT, Jennings G. The development of an autonomy scale. Contemp Fam Ther. 1994;16(4):329–345. doi:10.1007/BF02196884

45. Liu X, Huang XT, Bi CH. 青少年未来取向问卷的编制 [Development of the questionnaire for teenagers’ future orientation]. J Southwest Univ Soc Sci Ed. 2011;37(6):7–12. Chinese. doi:10.13718/j.cnki.xdsk.2011.06.021

46. Zimbardo PG, Boyd JN. Putting time in perspective: a valid, reliable individual-differences metric. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(6):1271–1288. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1271

47. Huebner ES. Conjoint analyses of the students’ life satisfaction scale and the Piers-Harris self-concept scale. Psychol Sch. 1994;31(4):273–277. doi:10.1002/1520-6807(199410)31:4<273::AID-PITS2310310404>3.0.CO;2-A

48. Zhang XG, He LG, Zhang X. 青少年学生生活满意度的结构和量表编制 [Adolescent students’ life satisfaction: its construct and scale development]. Psychol Sci. 2004;27(5):1257–1260. Chinese. doi:10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2004.05.068

49. Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide.

50. Little TD. Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 2013.

51. Schrodt P. Family strength and satisfaction as functions of family communication environments. Commun Q. 2009;57(2):171–186. doi:10.1080/01463370902881650

52. Boniwell I, Osin E, Linley PA, Ivanchenko GV. A question of balance: time perspective and well-being in British and Russian samples. J Posit Psychol. 2010;5(1):24–40. doi:10.1080/17439760903271181

53. Zhang JW, Howell RT, Stolarski M. Comparing three methods to measure a balanced time perspective: the relationship between a balanced time perspective and subjective well-being. J Happiness Stud. 2013;14(1):169–184. doi:10.1007/s10902-012-9322-x

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.