Back to Journals » Open Access Rheumatology: Research and Reviews » Volume 11

Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis

Authors Nosratzehi T, Nosratzehi S, Nosratzehi M, Ghaleb I

Received 9 July 2019

Accepted for publication 23 November 2019

Published 10 December 2019 Volume 2019:11 Pages 309—313

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OARRR.S222607

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Chuan-Ju Liu

Tahereh Nosratzehi,1 Shahin Nosratzehi,2 Mahin Nosratzehi,3 Iman Ghaleb4

1Dental Research Center, Department of Oral Medicine, School of Dentistry, Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran; 2Department of Endocrinology, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran; 3Department of Rheumatology, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran; 4Dentist, Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran

Correspondence: Tahereh Nosratzehi

Dental Research Center and Department of Oral Medicine, School of Dentistry, Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran

Tel +98-9152345423

Email [email protected]

Introduction: The assessment of the quality of life (QOL) in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients is of great importance for health researchers, health planners, and clinical specialists. Thus, the present study aimed to evaluate the oral health-related quality of life in patients with RA.

Materials and Methods: In this case–control study, data were collected by two standard questionnaires filled by 80 patients with rheumatoid arthritis and 80 healthy individuals. They were analyzed using independent t-test, chi-square test, Mann–Whitney test, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and Kruskal–Wallis test in SPSS 21.

Results: The mean of Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) score in RA patients and control groups was 1.17± 0.89 and 0.35±0.12, respectively, and the mean of General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) score in patients and control groups was 37.46±9.53 and 53.21±11.35, respectively; 62.5% of the patients got HAQ score more than or equal to 1 (≥1) and 91.2% got GOHAI score less than or equal to 50 (≤50).

Conclusion: The results of the present study suggested that most of the patients with RA had a poor oral health quality of life. Deterioration of disease and aging decrease the GOHAI and the oral health quality of life of patients.

Keywords: oral health-related quality of life, rheumatoid arthritis, general oral health assessment index

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an inflammatory systemic disorder with a prevalence of 0.5–1%, in women three times more than men.1 Clinical imaging includes the inflammation of the synovial joint, tendons, and structures around the joint.2 Rheumatoid arthritis is diagnosed by the accumulation of pro-inflammatory cells in the synovial membrane leading to synovitis, destruction of cartilage and musculoskeletal tissue, and ultimately the physical disorders as well as changes in systemic immune function.1 RA is a progressive chronic change which causes pain, deformity, and functional restricts, resulting in severe disabilities in daily activities and declining the quality of life.3

Studies suggested that there is a significant relationship among periodontitis, cardiovascular diseases, and rheumatoid arthritis; the risk of progression of periodontitis is 1.82 times more than that of healthy people. It is suggested that rheumatoid arthritis can exacerbate periodontium, or periodontitis can worsen the inflammation status of rheumatoid arthritis. A periodontal pathogen called Porphyromonas gingivalis can involve in this pathophysiology by stimulating the host proteins and make immunity system intolerant. P. gingivalis is the only known bacterium which can produce the peptidyl arginine deiminase (PAD) enzyme and human PAD homologous and converts arginine into citrulline.2

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis often have clinical and radiological symptoms of temporomandibular joint deformation. The most prevalent symptoms include pain and noise on temporomandibular joint motion, restricted mandibular movements, oedema, and pain on muscles of mastication.4 Moreover, RA often causes mental and physical impairment affecting interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal proximal joints; oral health may cause disorders in these patients and result in plaque accumulation and subsequently periodontal inflammatory disease.1

To assess the patients’ needs for oral–dental health, OHRQL has evolved to complete the clinical examinations.5 OHQOL depends upon the perception of individuals from their oral health and its symptoms they experienced. Meanwhile, cultural aspects, the history of the disease, and psychosocial health can be efficient.6,7 OHQOL self-assessment tools are self-explanatory and reflect the impact of oral health status on quality of life.6,8 Among the OHQOL measurement tools, the General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) was considered important in the study of the relationship between oral and dental diseases and the quality of life in the elderly.9

Generally, studies about the oral symptoms and oral health in RA patients are restricted. Assuming that there has not yet been a study in this area, the present study aimed to assess the quality of life associated with oral health in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Materials and Methods

This case–control study was performed on 80 patients with rheumatoid arthritis and 80 healthy individuals with no history of the systemic disease and drug use during the last year. After getting informed consent, the subjects were divided into two groups; they had inclusion criteria and homogeneity of age and sex. The activity of rheumatoid arthritis was analyzed based on the ESR, CRP, and DAS28 (disease activity score 28) tests. Considering the interpretations, if DAS28 < 3.2, then the disease is in remission mode; if DAS28 ≤ 5.1 ≥3.2, then it is moderate; and if DAS28 > 5.1, the disease is active. In addition, the number of joints involved in patients with rheumatoid arthritis was recorded. The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) contains 20 questions related to the ability to do daily activities including dressing, cleaning, walking, working out, and doing homework with 4 items: without problem = 0, a few problems = 1, many problems = 2, and inability = 3. Finally, to obtain the HAQ score, the total score was divided by the number of questions and the HAQ score was calculated.

The HAQ scores were divided into two levels: 1) having little difficulty doing activities (in the case of a score between zero and 1); and 2) having great difficulty resulting in the complete disability (when the mean of the score is greater than or equal to 1). The GOHAI is the most common indicator used in determining OHRQoL which assesses the effects of oral health on their abilities. The GOHAI questionnaire consists of 12 questions with 5 options: never = 5, rarely = 4, sometimes = 3, often = 2, and always = 1.

The Add-GOHAI score is in the range of 60 to 12. Add-GOHAI scores were divided into two groups: Dt-GOHAI = 0 (representing the poor quality of life; if Add-GOHAI ≤ 50) and Dt-GOHAI = 1 (representing moderate to a high quality of life if Add-GOHAI ≥ 50) groups.

Results

In the present study aiming at assessing the quality of life associated with oral health in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in clinics of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, data of 160 patients (80 patients and 80 healthy individuals) were collected and analysed. The mean age of participants in patients and control groups was 51.6 ± 14.8 and 50.2 ± 12.3 years, respectively. Independent t-test showed that there was not a significant relationship between both groups in terms of the mean of age (P = 0.618), and they were homogenous in this regard; 88.8% of the participants were female and 11.2% male. Chi-square test showed that there was not any significant difference between both groups in terms of gender ratio, and they are homogenous in this regard (P = 0.472).

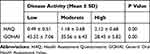

Table 1 displays a significant difference between the mean and standard deviation of HAQ and GOHAI in RA patients and control groups (mean score of HAQ in RA patients and control group is 1.17 ± 0.89 and 0.35 ± 0.12, respectively, and the mean score of GOHAI in RA patients and control groups is 37.46 ± 9.53 and 53.21 ± 11.35).

|

Table 1 Mean and Standard Deviation of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Indicators in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis and Healthy Individuals |

As Table 2 shows, HAQ was considered as level 2 in 62.5 patients and level 1 in 37.5 patients. Further, Dt-GOHAI = 0 and Dt-GOHAI = 1 were observed in 91.2% and 8.8% of the patients.

|

Table 2 Frequency Distribution of Subjects Based on the Levels of Quality of Life Indicators in RA Patients and Healthy Individuals |

As Table 3 shows, there is not a significant difference between HAQ and GOHAI in terms of gender (P > 0.05).

|

Table 3 Mean and Standard Deviation of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Indicators in the Group of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis in Terms of Gender |

Pearson correlation test showed that aging and the number of involved joints lead to increasing the HAQ index and decreasing the GOHAI (P < 0.05). The test shows that there is a significant direct correlation between the age and the number of involved joints with the HAQ index and a significant reverse relationship between the mentioned variables with the GOHAI (Table 4). The results of the study showed that 38.8% (31 patients) of the patients were a little active (low), 33.8% (27 persons) almost active (moderate), and 27.5% (22 people) highly active (high). The results showed that 18.8% of the patients (15 patients) had no involved joints, 31.3% (25 patients) had 2–5 joints, 25% (20 patients) had 6−10 joints, and the rest (25% patients) had more than 10 involved joints.

|

Table 4 The Relationship Between the Indicators of Quality of Life and Age and the Number of Involved Joints in RA Patients |

Table 5 shows that the mean difference of these indicators between both groups was statistically significant in terms of disease activity (P <0.05). Deterioration of disease increases HAQ and decreases GOHAI (Table 5).

|

Table 5 Mean and Standard Deviation of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Indicators in Terms of Disease Activity in RA Patients |

Table 6 shows that the mean difference of these indicators between both groups was statistically significant in terms of the number of involved joints (P < 0.05). In this regard, increasing the number of involved joints increases HAQ and decreases GOHAI.

|

Table 6 Mean and Standard Deviation of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Indicators Based on the Number of Involved Joints in RA Patients |

Discussion

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic inflammatory disorder which causes the destruction of joint and disability in patients and makes the joints, especially the animated joints dysfunction. Moreover, it shortens the life expectancy and affects the quality of life.10 Health-related quality of life is specifically associated with health and diseases which is a multidimensional concept. One of the subsections of health-related quality of life is related to oral health.11

Oral diseases and health can affect the quality of life and physical and mental health of individuals. Considering the role of the oral system in speaking, chewing, tasting, eating, people’s appearance, and self-confidence, it can lead to a great pleasure in life.12 The present study determined the oral health-associated quality of life in RA patients. The mean of the score of HAQ for RA patients and healthy subjects was 1.17 ± 0.19 and 35.0 ± 0.02, respectively; 62.5% of the patients had an HAQ score of ≥ 1, indicating that most patients had moderate-to-severe physical disabilities.

The results of the present study are consistent with those of Marra,13 Michaud,14 Corbacho,15 Arendse16, and Blaizot,4 and they estimated that the mean score of HAQ was between 1.05 and 1.66 as well. However, in the studies conducted by Shidara,17 Bjork,18 Ranganath19, and Shinozaki,20 the mean score of HAQ was lower than that of the present study and is not consistent. Han et al (2016) reported that the mean score of HAQ in RA patients was 76.6 ± 0.69, and 42.2% had HAQ score more than or equal to 1 (≥1), which was less than that of this study.21 It seems that the difference between the results of both studies (the recent studies and this study) can be due to the difference in duration of disease, the number of involved joints, and the duration of treatment. Using RA drugs can reduce the HAQ score by improving the physical status of patients.

Ahola et al (2015) examined the effect of rheumatoid arthritis on oral health and quality of life in Finland; they used Oral Health Impact (OHIP14) Profile for assessing the oral health-related quality of life.

The present study was done on 995 participants (564 RA patients and 421 patients in the control group). RA patients had more orofacial symptoms. Xerostomia (dry mouth) was reported in 19.6% and 2.9% of the patients, and temporomandibular joint symptoms were seen in 59.2% of the patients. Based on the OHIP-14 questionnaire, the mean score of patients (8.80 ± 11.15) was considerably more than that of the control group (3.93 ± 6.60).3

Gamal et al (2015) have performed a study on “the evaluation of quality of life in RA Egyptian patients”. They measured the quality of lives using a 36-question QA questionnaire. Their results suggest that the quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis was lower in the educated and unemployed. Further, the rheumatoid factor was positive and higher disease activity (the physical part of the questionnaire) was significantly lower in patients with more than five years’ history of disease.22

Wan et al (2016) have done studies on 108 RA patients in a study entitled “the health related quality of life and their predictors in RA patients”, and they reported the level of health-related quality of life compared to the general population.23

In the present study, the mean score of GOHAI in RA patients and control groups was 37.46 ± 9.53 and 53.21 ± 11.35, respectively, which was significant (P = 0.001). In 91.2% of the patients, the GOHAI scores were less than 50, indicating the poor quality of life and low living standards. According to Blaizot et al (2003), 58% of the patients had a poor quality of life, and this difference could be due to the level of education and socioeconomic status which was lower than that of the subjects in this study.4 RA patients complain of pain and hardness of joints and have great difficulty in walking, climbing the stairs, or doing the delicate work, and it can affect their quality of life dramatically. The results of the present study showed that there was a significant direct correlation between age and the number of involved joints and the HAQ index and a significant reverse relationship between the mentioned variables and the GOHAI. Deterioration of disease increases HAQ and decreases GOHAI.

Further, the results of the present study showed that the mean of HAQ and GOHAI indicators between males and females was not significantly different (P > 0.05). In a study by Taylor et al (2004) assessing the quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, female patients had lower scores in quality of life than men.24 According to IIKUNI et al, the mean score of HAQ in women was significantly higher than that of men, which is not consistent with the present study.25 The reason for this difference can be related to nature, prevalence, and etiology. On the other hand, since the majority of patients were female, a significant relationship is not seen. The higher scores of HAQ and GOHAI in the present study indicate a poor and unfavorable quality of life in RA patients. One of the reasons affecting this low quality is the unavailability of good health and unawareness of medical advice which requires more collaboration between the doctor, patient, and patient entourage.

Conclusion

The results of the present study showed that most of the RA patients had a poor oral health quality of life. Deterioration of disease and aging decrease the GOHAI and the oral health quality of life of patients.

Suggestions

Performing studies on the effects of rheumatoid arthritis drugs on improving the quality of life of RA patients and surveying the effect of improving the oral and periodontal conditions of patients on the amount of activity are suggested in further studies.

Ethics Statement

This study was approved by Zahedan University of Medical Sciences ethics committee (Ethics code: 7577), and all participants provided written informed consent.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Pischon N, Pischon T, Kroger J, et al. Association among rheumatoid arthritis, oral hygiene, and periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2008;79(6):979–986. doi:10.1902/jop.2008.070501

2. Monsarrat P, Vergnes JN, Blaizot A, et al. Oral health status in outpatients with rheumatoid arthritis: the OSARA study. Oral Health Dent Manag. 2014;13(1):113–119.

3. Ahola K, Saarinen A, Kuuliala A, Leirisalo-Repo M, Murtomaa H, Meurman JH. Impact of rheumatic diseases on oral health and quality of life. Oral Dis. 2015;21(3):342–348. doi:10.1111/odi.2015.21.issue-3

4. Blaizot A, Monsarrat P, Constantin A, et al. Oral health-related quality of life among outpatients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int Dent J. 2013;63(3):145–153. doi:10.1111/idj.12023

5. Slade GD, Strauss RP, Atchison KA, Kressin NR, Locker D, Reisine ST. Conference summary: assessing oral health outcomes–measuring health status and quality of life. Community Dent Health. 1998;15(1):3–7.

6. Tubert-Jeannin S, Riordan PJ, Morel-Papernot A, Porcheray S, Saby-Collet S. Validation of an oral health quality of life index (GOHAI) in France. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(4):275–284. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0528.2003.t01-1-00006.x

7. Allen PF. Assessment of oral health related quality of life. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1(1):40. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-1-40

8. Murariu A, Hanganu C, Bobu L. Evaluation of the reliability of the geriatric oral health assessment index (GOHAI) in institutionalised elderly in Romania: a pilot study. OHDMBSC. 2010;9(1):11–15.

9. Naito M, Suzukamo Y, Nakayama T, Hamajima N, Fukuhara S. Linguistic adaptation and validation of the General Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI) in an elderly Japanese population. J Public Health Dent. 2006;66(4):273–275. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.2006.tb04081.x

10. Akbarian M, Salehi I. Rheumatoid Arthritis. Tehran: Tehran University of Medical Sciences; 2006.

11. Guzeldemir E, Toygar HU, Tasdelen B, Torun D. Oral health-related quality of life and periodontal health status in patients undergoing hemodialysis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140(10):1283–1293. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0052

12. Hebling E, Pereira AC. Oral health-related quality of life: a critical appraisal of assessment tools used in elderly people. Gerodontology. 2007;24(3):151–161. doi:10.1111/ger.2007.24.issue-3

13. Marra C, Lynd L, Esdaile J, Kopec J, Anis A. The impact of low family income on self-reported health outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis within a publicly funded health-care environment. Rheumatology. 2004;43(11):1390–1397. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh334

14. Michaud K, Messer J, Choi HK, Wolfe F. Direct medical costs and their predictors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a three-year study of 7527 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(10):2750–2762. doi:10.1002/art.11439

15. Corbacho MI, Dapueto JJ. Assessing the functional status and quality of life of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2010;50(1):31–43. doi:10.1590/S0482-50042010000100004

16. Arendse R, Haraoui B, Choquette D, et al. FRI0579 What Is the Variability of HAQ Over Time in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis Treated with Anti-TNF?. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2016.

17. Shidara K, Inoue E, Hoshi D, et al. Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody predicts functional disability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a large prospective observational cohort in Japan. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32(2):361–366. doi:10.1007/s00296-010-1671-3

18. Bjork M, Trupin L, Thyberg I, Katz P, Yelin E. Differences in activity limitation, pain intensity, and global health in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Sweden and the USA: a 5-year follow-up. Scand J Rheumatol. 2011;40(6):428–432. doi:10.3109/03009742.2011.594963

19. Ranganath VK, Paulus HE, Onofrei A, et al. Functional improvement after patients with rheumatoid arthritis start a new disease modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) associated with frequent changes in DMARD: the CORRONA database. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(10):1966–1971.

20. Shinozaki M, Inoue E, Nakajima A, et al. Elevation of serum matrix metalloproteinase-3 as a predictive marker for the long-term disability of rheumatoid arthritis patients in a prospective observational cohort IORRA. Mod Rheumatol. 2007;17(5):403–408. doi:10.3109/s10165-007-0608-5

21. Han C, Li N, Peterson S. THU0043 minimal important difference in HAQ: a validation from health economic perspectives in patient with rheumatoid arthritis using real-world data from Adelphi database. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:193. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-eular.2009

22. Gamal RM, Mahran SA, El Fetoh NA, Janbi F. Quality of life assessment in Egyptian rheumatoid arthritis patients: relation to clinical features and disease activity. Egypt Rheumatol. 2016;38(2):65–70. doi:10.1016/j.ejr.2015.04.002

23. Wan SW, He H-G, Mak A, et al. Health-related quality of life and its predictors among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;30:176–183. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2015.07.004

24. Taylor WJ, Myers J, Simpson RT, McPherson KM, Weatherall M. Quality of life of people with rheumatoid arthritis as measured by the World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument, short form (WHOQOL-BREF): score distributions and psychometric properties. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(3):350–357. doi:10.1002/art.20398

25. Iikuni N, Sato E, Hoshi M, et al. The influence of sex on patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a large observational cohort. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(3):508–511. doi:10.3899/jrheum.080724

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.