Back to Journals » Clinical Ophthalmology » Volume 8

Neuroretinitis in ocular bartonellosis: a case series

Authors Raihan A, Zunaina E, Wan-Hazabbah W, Adil H, Lakana-Kumar T

Received 6 March 2014

Accepted for publication 29 April 2014

Published 5 August 2014 Volume 2014:8 Pages 1459—1466

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S63667

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 4

Abdul-Rahim Raihan,1 Embong Zunaina,1,2 Wan-Hitam Wan-Hazabbah,1,2 Hussein Adil,1,2 Thavaratnam Lakana-Kumar1

1Department of Ophthalmology, School of Medical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Kubang Kerian, Kelantan, Malaysia; 2Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia, Kubang Kerian, Kelantan, Malaysia

Abstract: We report a case series of neuroretinitis in ocular bartonellosis and describe the serologic verification for Bartonella henselae. This is a retrospective interventional case series of four patients who presented in the ophthalmology clinic of Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia from June 2012 to March 2013. All four patients had a history of contact with cats and had fever prior to ocular symptoms. Each patient presented with neuroretinitis characterized by optic disc swelling with macular star. Serology analysis showed strongly positive for B. henselae in all of the patients. All patients were treated with oral azithromycin (except case 4, who was treated with oral doxycycline), and two patients (case 1 and case 3) had poor vision at initial presentation that warranted the use of oral prednisolone. All patients showed a good visual outcome except case 3. Vision-threatening ocular manifestation of cat scratch disease can be improved with systemic antibiotics and steroids.

Keyword: cat scratch disease

Introduction

Cat scratch disease (CSD) is a self-limiting disease in immunocompetent patients. It is caused by infection of Bartonella henselae after contact with infected cats. B. henselae is a Gram-negative aerobic, fastidious, intracellular bacillus. Other Bartonella spp. known to cause systemic and ocular manifestation are Bartonella quintana, Bartonella grahamii, and Bartonella elizabethae.1,2 CSD is transmitted to humans through a cat scratch, cat bite, cat saliva, or cat flea bite.

Typical presentation of CSD is fever and lymphadenopathy. CSD may present in a wide spectrum of systemic manifestations, including endocarditis, hepatitis, encephalopathy, meningitis, transverse myelitis, hemolytic anemia, glomerulonephritis, and osteomyelitis. In immunocompromised patients, Bartonella infection can cause a vasoproliferative response as seen in bacillary angiomatosis which resembles Kaposi’s sarcoma histologically.3,4

Rarely, CSD with ocular bartonellosis manifests as Parinaud’s oculoglandular conjunctivitis and intraocular inflammation (uveitis) in the form of neuroretinitis or retinochoroiditis. Neuroretinitis was previously described as Leber’s idiopathic stellate neuroretinitis in 1916.5 It is characterized by optic disc swelling with partial or complete macular star,5 and occurs in 1%–2% of patients with CSD.6 Neuroretinitis in association with serologic evidence of Bartonella infection was documented in 1994.7–9

Serologic tests for Bartonella became readily available in recent years and are a means of establishing CSD diagnosis. Diagnosis of CSD is mainly by clinical presentation and is confirmed with positive serologic analysis for Bartonella. An increase in immunoglobulin (Ig) M titer with a significant increase in IgG antibodies titer can be considered an acute Bartonella infection.10

The aim of this retrospective interventional case series is to describe features of neuroretinitis and serologic verification of B. henselae for ocular bartonellosis.

Case series

This is a retrospective interventional case series of four patients who presented in the ophthalmology clinic at the Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia, Kubang Kerian, Malaysia from June 2012 to March 2013.

All four patients had a history of contact with cats; had fever prior to ocular symptoms; and presented with optic disc swelling and macular edema, and had positive serology for B. henselae. Table 1 shows the summary of the four patients concerning age and sex, systemic and ocular findings, and serologic analysis for B. henselae, comparing visual outcome and treatment given to the patients.

| Table 1 Summary of patients with ocular bartonellosis |

Case 1

A 15-year-old boy presented with gradual-onset, painless reduced vision of his left eye of 7 days’ duration. It was not associated with eye redness or eye discharge. He had high-grade fever for 1 week prior to eye symptoms, which had resolved spontaneously. The boy revealed a history of contact with cats at home.

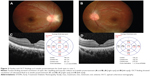

Physical examination showed a body temperature of 37.0°C. There was no skin lesion and no lymphadenopathy. Ocular examination revealed positive relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) in his left eye. Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of the right eye was 6/9, and was 6/90 in the left eye. His intraocular pressure was normal in both eyes. There was presence of bilateral nongranulomatous panuveitis. Fundus examination showed features of bilateral neuroretinitis characterized by optic disc swelling with partial macular star (Figure 1A and B). The optic disc swelling in the right eye was associated with disc hemorrhage superiorly. The retinal veins were dilated and tortuous in both eyes. The optic disc swelling was associated with bilateral macular edema. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) showed presence of bilateral subretinal fluid with loss of foveal depression (Figure 1C and D). There was also presence of intraretinal fluid in the right eye.

Blood analysis of full blood count, renal profile, and liver function test were within normal limits, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 48 mm per hour. Biochemistry, antinuclear antibodies (ANA), complement studies, and rheumatoid factor studies were normal. Serologic studies of cytomegalovirus (CMV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), toxoplasma, Leptospira, and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) were also negative. A chest radiograph was normal, and Mantoux test was negative. Serology analysis showed strongly positive IgM (titers 1:384) and IgG (titers 1:512) for B. henselae.

The boy was treated empirically with oral azithromycin 250 mg daily for 6 weeks. The patient was also treated with oral prednisolone 60 mg daily for 1 week; the oral prednisolone treatment was tapered down slowly within the next 1 month. After 6 weeks of systemic azithromycin therapy and oral prednisolone, there was improvement of visual acuity in the left eye (right eye: 6/9, left eye: 6/9) and bilateral resolving of optic disc swelling and macular star (Figure 2A and B). There was resolution of panuveitis and subretinal fluid in both eyes (Figure 2C and D).

Case 2

A 42-year-old Malay lady was referred to our clinic from a district hospital for sudden onset painless blurring of vision in the left eye of 5 days’ duration, which was associated with floaters and a central scotoma. However, there was no history of eye redness or eye discharge. She had a history of fever lasting 2 weeks prior to eye symptoms. She had a cat at home but there was no history of cat scratch.

Physical examination revealed a body temperature of 37.0°C with no lymphadenopathy. Her BCVA was 6/9 in the right eye and 6/30 in the left eye. She had positive RAPD in her left eye. Examination of the left eye showed optic disc swelling inferiorly and it was associated with multiple flame-shaped retinal hemorrhages. The macula was edematous with retinal exudates (Figure 3A). Ocular examination of the right eye was normal. OCT of the left eye showed presence of subretinal fluid (Figure 3B).

She was diagnosed to have diabetes mellitus with random blood sugar of 19 mmol/L. Blood examination of full blood count, liver function test, renal profile, and ESR were within normal limits. Serologic tests for ANA, complement studies, and rheumatoid factor studies were normal. Serologic studies for CMV, HIV, Leptospira, and VDRL were also negative. A serologic test detected toxoplasma IgG antibody, but its avidity was 63.5, which indicates past infection. A chest radiograph was normal, and Mantoux test was negative. Brain neuroimaging was also normal. B. henselae Ig titers were positive for IgM (titers 1:20) and IgG (titers 1:256).

The patient was treated with oral hypoglycemic agent for her newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus. For the ocular bartonellosis, she was treated with azithromycin 250 mg daily for 4 weeks. Follow-up at 1 month showed regression of optic disc swelling and resolving of macular edema with formation of partial macular star (Figure 3C). Two months after the initial visit, the visual acuity of the left eye had improved to 6/6 with complete resolution of optic disc swelling and macular edema (Figure 3D). Repeat OCT of the left eye showed resolution of the subretinal fluid (Figure 3E).

Case 3

A 23-year-old Malay man presented with sudden-onset blurring of vision in the right eye of 2 weeks’ duration, which was associated with a central scotoma and retrobulbar pain. However, there was no history of eye redness or eye discharge. He had a history of fever 3 days prior to the visual loss. He owned a cat at home but there was no history of cat scratch.

Physical examination revealed a body temperature of 37.0°C and presence of right submandibular lymphadenopathy. BCVA was counting fingers in the right eye and 6/7.5 in the left eye. There was absence of RAPD. Fundus examination of the right eye showed optic disc swelling associated with flame-shaped retinal hemorrhages. There was presence of focal retinitis lesion at the temporal and superior margins of the optic disc (Figure 4A). The optic disc swelling was associated with macular edema with retinal exudates. Ocular examination of the left eye was normal. OCT of the right eye showed presence of subretinal fluid (Figure 4B).

Blood examination of full blood count, liver function test, renal profile, and ESR were normal. Serologic tests for ANA, complement studies, and rheumatoid factor studies were normal. Serologic studies of CMV, HIV, Leptospira, and VDRL were also negative. A serologic test detected toxoplasma IgG antibody, but its avidity indicated past infection. A chest radiograph was normal, and Mantoux test was negative. Serology analysis for B. henselae was positive (IgM titers 1:96, IgG titers 1:512).

The patient was treated with azithromycin 250 mg daily for 6 weeks. The patient was also treated with oral prednisolone 60 mg daily for 1 week; the oral prednisolone treatment was tapered down slowly within the next 1 month. There was formation of macular star of the right eye at 1-week follow-up (Figure 4C). At follow-up at 6 weeks, there was a slight improvement in visual acuity of the right eye, from counting fingers to 6/90. There was regression of optic disc swelling and macular edema (Figure 4D). Repeat OCT of the right eye showed resolution of the subretinal fluid (Figure 4E).

Case 4

A 27-year-old Malay woman complained of painless, sudden blurred vision in the right eye of 1 day’s duration, which was associated with a superotemporal scotoma. However, there were no floaters or flashes of light and nor was there any eye redness or eye discharge. She reported having been scratched by her cat at home 1 week prior to visual loss. She had a history of fever 3 days prior to the eye symptoms.

Physical examination revealed a body temperature of 37.0°C with presence of right submandibular lymphadenopathy. However, there was no skin lesion. BCVA was 6/30 in the right eye and 6/9 in the left eye. There was absence of RAPD. Fundus examination of the right eye showed optic disc swelling at the inferior disc margin associated with macular star (Figure 5A). Ocular examination of the left eye was normal. OCT of the right eye showed presence of subretinal fluid (Figure 5B).

Blood examination of full blood count, liver function test, and renal profile were normal. Serologic tests for ANA, complement studies, and rheumatoid factor studies were normal. Serologic studies of CMV, HIV, toxoplasmosis, Leptospira, and VDRL were also negative. ESR was slightly elevated, at 44 mm per hour. Mantoux test showed 18 mm of reading, but a chest radiograph was normal. Neuroimaging of brain and orbit was also normal. Serology analysis for B. henselae was positive for IgM and IgG (1:96 and 1:512, respectively).

The patient was treated with oral doxycycline 100 mg 12-hourly for 4 weeks. At follow-up at 1 month, there was improvement of visual acuity of the right eye, from 6/30 to 6/7.5, with regression of optic disc swelling and prominent macular star (Figure 5C). Repeat OCT of the right eye showed resolution of the subretinal fluid (Figure 5D).

Discussion

Neuroretinitis affects 1%–2% of patients with B. henselae,6 and is characterized by optic disc swelling with partial or complete macular star.5 Typically, patients present with unilateral neuroretinitis,11 and bilateral neuroretinitis is a rare presentation. In our study, one patient (case 1) had bilateral CSD neuroretinitis and the remaining three patients had unilateral CSD neuroretinitis.

CSD is generally self-limiting. However, ocular bartonellosis with neuroretinitis may be complicated by retinal vascular occlusion causing permanent visual loss.12 Other posterior segment presentations of CSD include central retinal artery and vein occlusion, neovascular glaucoma, macular hole, choroiditis, retinal microgranuloma, serous macular detachment, and papillary vasoproliferative changes.13–15

Diagnosis of CSD is based on epidemiology of exposure to cats, fundus finding, and positive serology or culture of B. henselae. Approximately two-thirds of patients have positive serologic testing.16 Serologic testing for Bartonella by indirect immunofluorescence to detect serum anti-B. henselae antibodies has high sensitivities and specificities in immunocompetent patients.16 Isolation of Bartonella from blood or biopsy specimens is possible but difficult to yield, and growth of bacteria may require up to 4 weeks. Cross-reactions are well known between Bartonella spp. and, in the last 20 years, new zoonotic species were identified.17 Epidemiological evidence18 and experimental studies19 have demonstrated the important role of fleas in the transmission of B. henselae to cats.

High clinical suspicion of CSD as a cause of vision-threatening intraocular inflammation is necessary to initiate prompt antibiotic treatment. Early antibiotic treatment seems to improve visual outcome and hasten visual recovery.8,20 Recommended antibiotics for ocular bartonellosis include gentamicin, doxycycline, azithromycin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, and rifampicin, which have been reported to have good efficacy.20 Patients treated with corticosteroids for ocular bartonellosis had a good response in several studies.21–23 In our case series, two patients (case 1 and case 3) had poor vision at initial presentation that warranted the use of steroids. Moreover, a study done involving CSD-associated neuroretinitis in Japan reported a good outcome with antibiotics and steroids, and no relapse occurred in their patient.24

Conclusion

Ocular bartonellosis is a rare manifestation of CSD, and neuroretinitis is a typical presentation. The diagnosis is confirmed by positive serologic analysis for B. henselae. Vision-threatening ocular manifestation of CSD can be improved with systemic antibiotics and steroids.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Terrada C, Bodaghi B, Conrath J, Raoult D, Drancourt M. Uveitis: an emerging clinical form of Bartonella infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15 Suppl 2:132–133. | ||

O’Halloran HS, Draud K, Minix M, Rivard AK, Pearson PA. Leber’s neuroretinitis in a patient with serologic evidence of Bartonella elizabethae. Retina. 1998;18(3):276–278. | ||

Chomel BB. Cat-scratch disease and bacillary angiomatosis. Rev Sci Tech. 1996;15(3):1061–1073. | ||

Koehler JE. Bartonella-associated infections in HIV-infected patients. AIDS Clin Care. 1995;7(12):97–102. | ||

Harper SL, Chorich III LJ, Foster CS. Bartonella. In: Foster CS, Vitale AT, editors. Diagnosis and treatment of uveitis. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002:260–263. | ||

Carithers HA. Cat-scratch disease. An overview based on a study of 1,200 patients. Am J Dis Child. 1985;139(11):1124–1133. | ||

Cunningham ET, Koehler JE. Ocular bartonellosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130(3):340–349. | ||

Reed JB, Scales DK, Wong MT, Lattuada CP Jr, Dolan MJ, Schwab IR. Bartonella henselae neuroretinitis in cat scratch disease. Diagnosis, management, and sequelae. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(3):459–466. | ||

Golnik KC, Marotto ME, Fanous MM, et al. Ophthalmic manifestations of Rochalimaea species. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;118(2):145–151. | ||

Metzkor-Cotter E, Kletter Y, Avidor B, et al. Long-term serological analysis and clinical follow-up of patients with cat scratch disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(9):1149–1154. | ||

Florin TA, Zaoutis TE, Zaoutis LB. Beyond cat scratch disease: widening spectrum of Bartonella henselae infection. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5): e1413–e1425. | ||

Earhart KC, Power MH. Images in clinical medicine. Bartonella neuroretinitis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(20):1459. | ||

Gray AV, Michels KS, Lauer AK, Samples JR. Bartonella henselae infection associated with neuroretinitis, central retinal artery and vein occlusion, neovascular glaucoma, and severe vision loss. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(1):187–189. | ||

Asensio-Sánchez VM, Rodrĺguez-Delgado B, Garcĺa-Herrero E, Cabo-Vaquera V, Garcĺa-Loygorri C. [Serous macular detachment as an atypical sign in cat scratch disease]. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2006;81(12): 717–719. Spanish. | ||

Albini TA, Lakhanpal RR, Foroozan R, Holz ER. Macular hole in cat scratch disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(1):149–151. | ||

Suhler EB, Lauer AK, Rosenbaum JT. Prevalence of serologic evidence of cat scratch disease in patients with neuroretinitis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(5):871–876. | ||

Maurin M, Eb F, Etienne J, Raoult D. Serological cross-reactions between Bartonella and Chlamydia species: implications for diagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(9):2283–2287. | ||

Chomel BB, Abbott RC, Kasten RW, et al. Bartonella henselae prevalence in domestic cats in California: risk factors and association between bacteremia and antibody titers. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33(9):2445–2450. | ||

Chomel BB, Kasten RW, Floyd-Hawkins K, et al. Experimental transmission of Bartonella henselae by the cat flea. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34(8):1952–1956. | ||

Rolain JM, Brouqui P, Koehler JE, Maguina C, Dolan MJ, Raoult D. Recommendations for treatment of human infections caused by Bartonella species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(6):1921–1933. | ||

Brusaferri F, Candelise L. Steroids for multiple sclerosis and optic neuritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. J Neurol. 2000;247:435–442. | ||

Matsuo T, Yamaoka A, Shiraga F, et al. Clinical and angiographic characteristics of retinal manifestations in cat scratch disease. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2000;44(2):182–186. | ||

Kerkhoff F, Ossewaarde J, de Loos WS, Rothova A. Presumed ocular bartonellosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83(3):270–275. | ||

Kodama T, Masuda H, Ohira A. Neuroretinitis associated with cat-scratch disease in Japanese patients. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2003;81(6):653–657. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.