Back to Journals » Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management » Volume 13

Near-fatal asthma responsive to mepolizumab after failure of omalizumab and bronchial thermoplasty

Authors Menzella F , Galeone C, Lusuardi M, Simonazzi A, Castagnetti C, Ruggiero P, Facciolongo N

Received 23 August 2017

Accepted for publication 28 September 2017

Published 8 November 2017 Volume 2017:13 Pages 1489—1493

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S149775

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Garry Walsh

Francesco Menzella,1 Carla Galeone,1 Mirco Lusuardi,2 Anna Simonazzi,1 Claudia Castagnetti,1 Patrizia Ruggiero,1 Nicola Facciolongo1

1Department of Medical Specialties, Pneumology Unit, Arcispedale Santa Maria Nuova – IRCCS, Azienda USL di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, 2Unit of Respiratory Rehabilitation, Azienda USL di Reggio Emilia, S. Sebastiano Hospital, Correggio, Italy

Abstract: Severe asthma affects between 5% and 10% of patients with asthma worldwide and requires best standard therapies at maximal doses, but there is a subgroup of patients refractory to all treatments. We share a case report of a 53-year-old woman with a history of severe allergic asthma that progressively worsened over the years despite the best therapy. She had been hospitalized 35 times, including nine admissions to the respiratory intensive care unit due to severe exacerbations. To rule out other possible diagnoses, several investigations were performed, such as computed tomography scan of the chest and neck, fiberoptic laryngoscopy, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, and complete blood cell count. The patient was first treated with omalizumab, which was completely ineffective, and then with bronchial thermoplasty (BT), again without clinical benefit. The situation remained critical for about 3 months during the last hospitalization, but in February 2017, the Italian Medicines Agency approved the treatment of severe refractory eosinophilic asthma with mepolizumab (Nucala®). Given a blood eosinophil count of 300 cells/µL, our patient was started on 100 mg mepolizumab treatment. After the second administration, symptoms improved progressively, with a reduction in the number and severity of exacerbations, so the patient could finally be discharged from hospital. At follow-up, it was possible to reduce and then suspend oral corticosteroids by continuing only with inhaled corticosteroids/long-acting beta-agonists and montelukast. No further asthmatic exacerbations occurred; symptom control and quality of life improved significantly. To our knowledge, this is the first case of a patient unresponsive to omalizumab and BT but with excellent clinical response to mepolizumab. She is also the first patient to be treated with an anti-IL5 agent in Italy in a real-life clinical setting. The availability of new effective biological agents will allow many patients to resume as normal a life as possible, with a positive outcome also from a social and economic point of view.

Keywords: severe asthma, omalizumab, bronchial thermoplasty, mepolizumab, exacerbation, eosinophilia

Introduction

Severe asthma affects between 5% and 10% of patients with asthma and requires best standard therapies at maximal doses. Over 50% of the costs are absorbed by this disease in the Western countries.1 Frequent use of oral corticosteroids (OCS) involves systemic side effects that are often irreversible and serious. There is a subgroup of patients refractory to all treatments, including OCS, who have a poor control of asthma symptoms with recurrent exacerbations. This leads to a serious deterioration in the quality of life (QoL), loss of working or school days, and increased individual and social costs with consistent consumption of health care resources including hospitalization in the intensive care unit (ICU).1,2 The advent of omalizumab and subsequently of bronchial thermoplasty (BT) have made it possible to meet the needs of a significant number of patients with severe refractory asthma. However, many subjects are poor candidates for these new therapeutic options because they are unsuitable or do not respond satisfactorily, since there are no predictive biomarkers yet in the real-life setting to guide treatment. The choice is made even more difficult since asthma is a heterogeneous syndrome that can be better described as a constellation of phenotypes or endotypes, each with distinct cellular and molecular mechanisms, rather than as a single disease.3 One of these phenotypes is eosinophilic asthma, and the recent availability of a new biological agent like mepolizumab, an anti-IL5 monoclonal antibody (mAb), can help clinicians to treat this subgroup of patients effectively.4 A certain percentage of subjects may have characteristics that can indicate treatment with both omalizumab or mepolizumab, but there are currently no head-to-head studies which make it possible to give definite recommendations for the preferential use of one agent versus the other.

Here we describe the case of a patient with a form of near-fatal asthma resistant to all treatments including omalizumab and BT but who showed a dramatic response to mepolizumab, the first Italian product in a real-life clinical setting after the approval by the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Case report

A 53-year-old female Caucasian nonsmoker had a history of severe allergic asthma since 1999, which started after a pregnancy and progressively worsened over the years despite best standard therapy and optimal compliance. This patient had a body weight of 52 kg; was allergic to dust mites, Cladosporium herbarum, dog and cat epithelium, grass, pellitory, and cypress; and had a total serum IgE level of 115 IU/mL. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) was 75% of predicted, FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio was 65%, with a significant reversibility (>12%) at the bronchodilator test with 400 μg inhaled salbutamol.

She was employed as a supermarket cashier and her clinical history included several comorbidities such as gastro-esophageal reflux, regular treatment with proton-pump inhibitors, hypothyroidism, steroid-induced osteoporosis, and bilateral cataracts. Between 1999 and 2016, she had been hospitalized 35 times, with further 11 emergency room visits due to increasingly frequent severe asthma exacerbations, despite regular courses with OCS, taken for more than 6 months a year, in addition to maximal dosage of long-acting beta-agonists (LABA) and inhaled corticosteroids (ICS). Over the last 5 years, the patient had to be admitted to the respiratory intensive care unit (RICU) nine times, for noninvasive mechanical ventilation with face mask due to severe asthma exacerbation with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure.

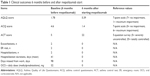

Given the bad control of asthma, the patient was enrolled in the INNOVATE trial in 20025 and then treated with omalizumab as add-on therapy to formoterol/budesonide (160/4.5 μg) with two inhalations twice daily and as needed (twice a day on an average). Unfortunately, at the third dose, the experimental therapy was suspended due to a skin rash. In the following years, the therapy was modified by replacing budesonide/formoterol with beclomethasone/formoterol extrafine (100/6 μg) two inhalations twice daily plus as needed, montelukast 10 mg daily, tiotropium bromide 18 μg per day, theophylline 300 mg twice daily, and methylprednisolone 4 mg daily (to be increased in case of an exacerbation). Differential diagnosis investigations were performed, in particular antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) and high-resolution chest computed tomography (CT) negative for vasculitis ruled out eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, also known as Churg-Strauss syndrome. In 2012, the patient was enrolled in a single-center clinical protocol on BT6 (Alair™; Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA); since FEV1 was above 60% of predicted and considering the poor control of asthma, she underwent three scheduled sessions as per the standard protocol. Baseline scores of asthma control test, asthma control questionnaire, and Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire are reported in Table 1, which shows a very poor control of the disease with really bad QoL.

After the third session of BT, an asthmatic crisis occurred which required hospitalization in RICU. Endobronchial biopsies and bronchoalveolar lavage were taken from lobes treated during the session. These procedures showed the presence of intraepithelial eosinophils and lymphocytes and prominent smooth muscle and goblet cell hyperplasia. After an initial improvement in asthmatic symptoms, however, the asthma severity returned to the baseline level within 12 months.

Considering the ineffectiveness of BT and the recurrent asthma exacerbations, in 2013 we decided to try again with omalizumab (Xolair®; Novartis Pharma, Basel, Switzerland), discontinued earlier in 2002 because of an adverse skin reaction during the INNOVATE trial. Before starting regular treatment, a drug provocation test was carried out with the commercial drug in the prefilled syringe. The patient did not manifest any allergic reactions and, based on a total IgE level of 115 IU/mL and a body weight of 56 kg, we started therapy with omalizumab 300 mg administered by subcutaneous (SC) injection every 4 weeks. We hypothesize that the adverse reaction to the trial drug but not to the commercial drug was probably due to different excipients of the two formulations. Again, a lack of improvement in asthma control led to interruption of the therapy after 12 months.

The patient was again admitted to our RICU in December 2016 due to a very severe asthma exacerbation with acute respiratory failure. Treatment required mechanical ventilation, intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone, oxycodone, beta-2 agonists and anticholinergic bronchodilators, and ICS, but due to recurrent severe bronchospasm, SC adrenaline, IV magnesium sulfate, morphine sulfate, and high dosage steroid boluses had to be administered as needed almost daily. After 4 weeks, the patient was discharged following a satisfactory clinical improvement, but after 7 days she was readmitted to RICU for a new severe asthma exacerbation. To rule out other causes of clinical deterioration, a number of tests were carried out: CT scan of chest and neck, fiberoptic laryngoscopy, 24-hour urine collection for catecholamines and metanephrines (to rule out pheochromocytoma), serum tryptase, and ANCA. Despite systemic steroids, the complete blood cell count revealed a peripheral eosinophilia of 300 cells/μL.

The clinical picture remained critical until February 2017, when AIFA approved mepolizumab (Nucala®; GlaxoSmithKline, Brentford, UK) for the treatment of severe refractory eosinophilic asthma. Based on blood eosinophil levels, on February 26, we immediately started treatment with mepolizumab 100 mg, to be administered SC once every 4 weeks. After the second administration, asthma symptoms improved progressively, and the patient was finally discharged on April 11. In the following period and after the sixth dose, it was possible to reduce and then suspend OCS and theophylline, continuing regular treatment only with ICS/LABA and montelukast. No further asthmatic exacerbations occurred while symptoms and QoL progressively improved allowing the patient to resume her job (Table 1).

Discussion

The availability of new therapeutic strategies, both pharmacological and interventional such as omalizumab and BT, respectively, has proved to improve management of severe asthma in patients eligible for these treatments.7 Unfortunately, many patients have been excluded because they are unsuitable or do not show a positive outcome and also because there are no reliable biomarkers yet predictive of clinical response. At present, omalizumab is considered the gold standard treatment in severe allergic asthma, with positive clinical outcomes represented by a reduction of exacerbations, OCS sparing effect, and an improvement of QoL.8 In clinical studies, such as the INNOVATE and other six studies on severe atopic asthmatics, baseline IgE was the only predictor of omalizumab efficacy since statistical significance was reached in the upper IgE quartile (p<0.001).5,9 Our patient had an IgE level of 115 IU/mL, a low value likely predictive of a negligible response to the anti-IgE treatment.

Our patient underwent a subsequent BT without any clinical benefit. It is not easy to identify the cause(s) of such a poor outcome in this single case, although it is well known that BT has a clinical effectiveness varying between 50% and 75% among the treated patients.10 An incorrect selection of the asthma phenotype really suitable for BT may also have occurred. Beyond the traditional clinical and inflammatory classification, phenotyping has recently been proposed also according to the type of airway smooth muscle (ASM).11 In vitro studies, mainly on animal models, have shown two types of ASMs: the first one is called “hyperreactive” (characterized by some markers such as sm-α-actin expressing exaggerated contractile response to external stimuli) and the second one is named “secretive” (characterized by the ability to produce cytokines). These asthma phenotypes are not separated and can often turn one into the other by identifying a “switching” phenotype.

A recent post hoc analyses on patients previously enrolled in two randomized clinical trials (RCTs) on mepolizumab showed that the anti-IL-5 agents can be effective in patients nonresponsive to omalizumab, with a steroid-sparing effect.12 Eosinophilic asthma is a distinct phenotype accounting for about 50% of asthmatic patients, which is clinically characterized by corticosteroid responsiveness and severity of impairment correlating with the level of eosinophilic inflammation. The main pathological peculiarity is represented by thickening of the basement membrane, ie, subepithelial fibrosis, in the airway mucosa;13,14 structural remodeling is particularly prominent in the severe forms of the disease with reduced response to treatments.15 Among asthma phenotypes, literature shows that the potential responders to anti-IL-5 mAbs, mepolizumab in particular, are subjects with persistent systemic and airway eosinophilia (>0.3×109/L in blood, >3% in sputum), poor symptom control, and high exacerbation rate despite treatment with high doses of inhaled and systemic corticosteroids.16 Since the populations eligible for mepolizumab or omalizumab partially overlap, a multicenter RCT is in progress to evaluate the effect of mepolizumab in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma previously unsuccessfully treated with omalizumab.17

As far as we know, this is the first case of a patient unresponsive to omalizumab and BT but with excellent clinical response to mepolizumab. She is also the first patient treated with this anti-IL5 mAb in Italy in a real-life setting.

The patient had an allergic and eosinophilic asthma subtype, with potential indication to both omalizumab and mepolizumab. Only the latter, recently introduced in clinical practice, made it possible to gain control of an otherwise critical and potentially fatal situation. Very important outcomes were the possibility of stopping OCS treatment in the presence of steroid-induced comorbidities and gaining optimal control of a severe unstable asthma, refractory to any other innovative treatment including omalizumab and BT. The absence of any exacerbation after the onset of mepolizumab therapy allowed marked improvement in the QoL and the return to normal life including work activity.

This case report is an interesting example of how effective a personalized approach to treatment conjugating research at a molecular level and clinical definition of target phenotypes can be. Cost-benefit considerations, however, imply that new, expensive treatments require a careful and thorough evaluation of patients by clinicians, while researchers still have much to investigate to identify outcome predictors.

Disclosure

Francesco Menzella participated in contracted research and clinical trials for Novartis and Sanofi, and has received lecture fees and advisory board fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Mundipharma, and Novartis. Nicola Facciolongo served as a consultant for Boston Scientific and has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca and Chiesi. The other authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Accordini S, Corsico AG, Braggion M, et al. The cost of persistent asthma in Europe: an international population-based study in adults. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;160(1):93–101. | ||

Klaustermeyer WB, Choi SH. A perspective on systemic corticosteroid therapy in severe bronchial asthma in adults. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2016;37(3):192–198. | ||

Canonica GW, Senna G, Mitchell PD, O’Byrne PM, Passalacqua G, Varricchi G. Therapeutic interventions in severe asthma. World Allergy Organ J. 2016;9(1):40. | ||

Menzella F, Lusuardi M, Montanari G, Galeone C, Facciolongo N, Zucchi L. Clinical usefulness of mepolizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2016;12:907–916. | ||

Humbert M, Beasley R, Ayres J, et al. Benefits of omalizumab as add-on therapy in patients with severe persistent asthma who are inadequately controlled despite best available therapy (GINA 2002 step 4 treatment): INNOVATE. Allergy. 2005;60(3):309–316. | ||

Arcispedale Santa Maria Nuova-IRCCS. Bronchial Thermoplasty: Effect on Neuronal and Chemosensitive Component of the Bronchial Mucosa (BT-ASMN); 2014. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01839591. Accessed June 3, 2017. [NLM Identifier: NCT01839591]. | ||

Fajt ML, Wenzel SE. Development of new therapies for severe asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2017;9(1):3–14. | ||

Normansell R, Walker S, Milan SJ, Walters EH, Nair P. Omalizumab for asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; (1):CD003559. | ||

Bousquet J, Rabe K, Humbert M, et al. Predicting and evaluating response to omalizumab in patients with severe allergic asthma. Respir Med. 2007;101(7):1483–1492. | ||

Bicknell S, Chaudhuri R, Lee N, et al. Effectiveness of bronchial thermoplasty in severe asthma in “real life” patients compared with those recruited to clinical trials in the same center. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2015;9(6):267–271. | ||

Wright DB, Trian T, Siddiqui S, et al. Phenotype modulation of airway smooth muscle in asthma. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2013;26(1):42–49. | ||

Magnan A, Bourdin A, Prazma CM, et al. Treatment response with mepolizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma patients with previous omalizumab treatment. Allergy. 2016;71(9):1335–1344. | ||

Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, et al. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(5):388–395. | ||

Hasegawa K, Stoll SJ, Ahn J, Bittner JC, Camargo CA Jr. Prevalence of eosinophilia in hospitalized patients with asthma exacerbation. Respir Med. 2015;109(9):1230–1232. | ||

Pepe C, Foley S, Shannon J, et al. Differences in airway remodeling between subjects with severe and moderate asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(3):544–549. | ||

Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, et al. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(13):1198–1207. | ||

GlaxoSmithKline. Omalizumab to mepolizumab switch study in severe eosinophilic asthma patients; 2016. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02654145. Accessed July 4, 2016. [NLM Identifier: NCT02654145]. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.