Back to Journals » Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare » Volume 7

Men as caregivers of the elderly: support for the contributions of sons

Authors Collins C

Received 24 May 2014

Accepted for publication 9 July 2014

Published 11 November 2014 Volume 2014:7 Pages 525—531

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S68350

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Cynthia R Collins

Loyola University New Orleans, College of Social Sciences/School of Nursing, New Orleans, LA, USA

Abstract: Emerging practice research on filial sources of health care support has indicated that there is a growing trend for sons to assume some responsibility for the health care needs of their aging parents. The purpose of this work is to propose that outcomes observed through a secondary analysis of data from a previous mixed methods research project, conducted with a sample of 60 elderly women residing in independent living centers, supports this concept in elder care. The present study is a retrospective interpretation utilizing the original database to examine the new question, “What specific roles do sons play in caregiving of their elderly mothers?” While daughters presently continue to emerge in existing health care studies as the primary care provider, there is a significant pattern in these data for older patients to depend upon sons for a variety of instrumental activities of daily living. As the baby-boomers age, there is more of cohort trend for their families to be smaller, adult daughters to be employed, and for adult children to be more geographically mobile. These factors may combine to make health care support networks more limited for the current aging population, challenging the elderly and their health care providers to revisit the cultural gender norms that are used to identify caregivers.

Keywords: sons as caregivers, male caregivers, aging parents, filial support, informal caregivers

Introduction

Are nurse practitioners, physicians, social workers, and other primary health care providers overlooking a potential resource when developing a plan of care for community-dwelling elderly? Within the current context of an aging population, men can no longer be considered bystanders as caregivers to their aging parents. The unprecedented cohort of persons over the age of 65 years increases daily. Projections are that this age cohort will expand from 39 million in 2010 to an expected 72 million by the year 2030.1 This phenomenon is a direct result of the maturing and increased lifespan of the baby-boom generation (born between 1946 and 1964). The fastest growing segment of the geriatric population will continue to be that of the oldest old (aged 85 and over), with a projected 240% increase in cohort size by 2040.1 Along with an increase in numbers of the aged expected to enjoy a longer lifespan is a predicted increase in seniors living with one or more chronic illnesses that will require some type of informal care.2 There is an emerging, yet largely unrecognized, societal trend for men to begin to fill the gaps as caregivers to community-dwelling elder parents.3–6 Recent national surveys suggest that approximately one in every three caregivers is a man. An estimated 30% of these male caregivers are sons.7 It is believed that the number of male caregivers, particularly sons, is underestimated due to studies that poorly address men as family caregivers.8 For example, descriptive studies of sons as family caregivers often narrowly define the term “caregiving” to one set of behaviors, or only include sons as a numerical comparison group to daughters in the role of primary care providers, without studying those variables that are unique to a son’s parental caregiving experiences.9 Furthermore, interventions aimed at relieving caregiver burden are often constructed and promoted to assist daughters, not sons.10 The purpose of this article is to demonstrate that outcomes observed through a secondary analysis of data from a previous mixed methods research project support the need to direct future research efforts to discovering the role of sons as family caregivers of the elderly.

Background of the problem

Men as caregivers

While there has been some effort in the literature to study men in the role of husbands and caregivers, particularly when these husbands are caregivers to Alzheimer’s patients, there is a scarcity of research that explores the roles of men who are adult sons and caregivers to their older parents.11–13 In an important qualitative study of paired adult siblings with older parents in need of assistance, Matthews14 identified significant factors that have prevented researchers from obtaining an accurate picture of the involvement of adult sons in caregiving exchanges with their older parents. Gender differences often exist among siblings as to what the “best practice” for informal care of aging parents ought to be in the family context.14 Matthews14 proposes that men view their relationship with older parents as more “filial” or “egalitarian” and therefore will often wait until assistance in daily living is requested of them by their parents. In reality, men are more often “care managers” of services and provide a good deal of support, but with the goal of helping their parent(s) to regain independence and self-reliance as much as possible.

A few existing studies have validated that adult sons, especially those separated from aging parents by distance, such as during military deployment, express worry and concern for meeting caregiving needs.15,16 Clinical experience in working with families has suggested to practitioners that there exist several situations in which adult sons have assumed a larger burden of care for their older parents. The literature supports this observation, most notably when the son is an only child or there are no daughters in the family unit.17 In a recent descriptive correlational study of 689 senior subjects residing independently in community care residential communities, when asked to identify their current or potential primary supporter by family relationship, 13% choose their adult sons. In that study, when married elderly subjects’ responses were compared with unmarried subjects, 59.3% of unmarried older adults had identified their adult sons as their primary supporter.18 Additionally, there is some support in the literature for sons as caregivers when the adult daughter in the family lives at a distance, has her own health issues, or experiences competing family stressors.19,20 Under these circumstances, the adult son may become the primary caregiver to the aged parent(s), and may do a remarkable job in providing a complex network of informal and formal services.

A beginning approach to the study of sons as caregivers to their elderly parents may be to examine the incidence of activities of daily living (ADLs) as compared with the provision of instrumental ADLs (IADLs).21 Again, there is a paucity of studies that have been conducted in this area when searched for the last 10 years, and even fewer within the United States. In a recent study in Spain, both ADL and IADL incidents of support were assessed in a cross-sectional study of 1,272 adult children who were primary caregivers to their community-dwelling older parents.10 Over all outcome measures, the researchers discovered that there were no statistical gender differences found between the total amounts of support provided by adult children to their aged parents. In the provision of ADLs, the only activity for which a statistical gender difference was found was when it came to providing bathing or personal hygiene; as might culturally be expected, daughters provided significantly more incidents of this type of care. With regard to provision of all IADLs, there were no significant gender differences. In a Taiwanese study of 12,166 adult child caregivers that measured IADL provision among sons and daughters, significantly higher incidents of sons as IADL providers, when compared with daughters, in these roles were found.22 This was particularly evident in the amounts of financial help, material (food and clothing) support, and health care information exchanged. The effect was even stronger for married sons. In a descriptive correlational study in Pennsylvania, a cross-sectional study population, including 5,458 adult child–older parent dyads, was surveyed using a dependent variable with a broad definition of “help”, which included both ADL and IADL measures.23 In that study, sons were more likely than daughters to provide incidents of assistance or help to their aging parents. However, daughters were more likely to be the providers when the type of care required involved more time and physical contact with the older parent. An additional significant gender difference was found among unmarried and married adult children. In this study, unmarried adult children of both sexes provided more incidents of supportive help than married children. In another study, researchers found that an elderly person’s measure of life satisfaction was higher when IADLs were reciprocally exchanged between the generations.24 A pattern of intergenerational support emerged where the older generation was more likely to receive IADL support, while the younger generation was more likely to receive either financial support or childcare from the older generation. The purpose of the current study is to demonstrate that the outcomes observed in this suburban population support the need to direct future research efforts to discovering the role of sons as family caregivers of the elderly.

Methodology

The study population

The study population was comprised of a nonprobability purposive sample of 60 elderly widowed women residing in three independent living centers, located within continuing care communities in suburban Maryland. Participation in the study was limited to only those subjects who possessed the following characteristics: 1) a self-rated health status of good or excellent, 2) one or more adult children, 3) a marital status of widowed for a period of 2 years or more, 4) a private residence which is independent of her children’s residences, 5) an oriented mental status, and 6) vision and hearing skills that allow for reading the questionnaire and engaging in normal conversation. The latter two characteristics of participants were insured through documentation by the elder’s primary physician, as required by the administrative procedures inherent in the facilities’ residency requirements. After obtaining approval from the human subjects review boards of the author’s academic affiliation and the ethics boards of the facilities involved, subjects were recruited by referral for participation in this study. Initial contact was made with nurse residents who agreed to identify subjects that might meet the criteria of the study, and would be willing to participate. A preliminary phone call was made by the referring nurse to obtain the subject’s consent to be contacted by the researcher.

Subjects in this study were protected in several ways: 1) participation was voluntary, 2) subjects were advised that they could withdraw from the study at any time during collection of the data, 3) written informed consent was obtained by the author prior to conducting the interview, 4) confidentiality was protected throughout the study by the use of coding procedures to disguise identities, 5) study data was stored separately from identifying data, and 6) the audio tapes were destroyed after transcription.

In the original study, the data were obtained through completed questionnaires and by means of a recorded interview conducted by the author in each of the subjects’ homes, using a formatted focused interview tool. The interview guide consisted of open-ended questions and had been pretested for content validity with an expert panel of six experienced geriatric researchers, as well as with a sample pilot population of four older women who met the criteria of the study. Each of the interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes (M [mean] =45). The interviews were audiotaped and later transcribed verbatim. A secondary review of the original data in its entirety revealed three sources of data that suggested sons’ participation in their older mothers’ care. The sources of data used to address the current research question were 1) demographic data forms including the identification of the number and age of each of their adult children, 2) questions in the interview in which subjects were asked to identify which IADLs/ADLs each adult child had assisted them in doing over the last 30 days, and 3) subject responses to the researcher’s question to describe the incidents of care.25

Data analysis

The demographic characteristics of the elder study subjects are listed in Table 1. Additionally, all subjects were Caucasian, and the mean age of the sample was 76.03 years, with an age range of 68–89 years. As an aggregate, the sampled widows identified 204 adult children (114 female and 90 male). The mean age of the adult children was 45.5 years, with an age range of 38–57 years. The mean number of adult children per respondent was three.

| Table 1 Demographic variables for elder women’s population sample (N=60) |

The original descriptive qualitative study addressed the question: “How do their interpersonal relationships with adult children influence the older person to engage in health promoting behaviors?”25 The purpose of this initial study was to explore the relationships between older persons and their adult children, with the goals of discerning and describing the patterns of intergenerational support exchanges and their subsequent impact upon the older person’s well-being. A constant comparison approach was used to collect and analyze the data, resulting in the identification of several patterns of filial exchange that were suggested by observing this population.26 The present study is a secondary analysis utilizing subsets of the original data to examine the new question: “What specific roles do sons play in caregiving of their elderly mothers?” The subjects’ prior recorded responses to the question: “In the last month, which of the following types of support did each of your adult children provide to you?” were isolated from these data. Caregiving tasks were categorized according to ADLs or IADLs. Specifically, ADLs were considered to include the following: help with bathing, dressing, toileting, and eating. IADLs were operationalized to include the following: ability to use the phone/computer, shopping for food/clothing, preparing food, housekeeping, laundry, obtain transportation for medical care/health promotion activities, taking medications as prescribed, and managing finances. Interview responses were sorted from these data in which subjects discussed specific incidents of support received from adult children. Incidents of social support were separated by sex of the adult child as identified by the elderly subject. Applying an analytic approach, paradigm cases, thematic analysis, and analysis of exemplars, these data were extracted from the transcribed interviews with the subjects.27

Findings

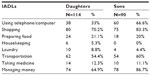

The secondary analysis of these data permitted a closer examination of subjects’ responses that described the specific contributions to both the health promotion and the health care of the subjects that were made by their adult sons and daughters, respectively. Specifically, recent episodes of filial provision of ADLs and IADLs were enumerated and compared by sex. In this study, as supported by previous literature, daughters surpassed sons in the provision of all ADLs. However, when compared by sex, sons of these subjects fared closely in their provision of IADL supportive behaviors with daughters in certain important areas, over the most recent month. It is a discussion of those similarities and differences between the sexes in the provision of IADLs that will be discussed in the remaining paper. The outcomes were analyzed and are presented here as a comparison by sex of the total identified incidents of IADL support identified by the older subject (Table 2).

| Table 2 Distribution by sex of provision of IADLs by adult children in the last month |

In this sample, sons exceeded daughters in providing their mothers with health-related assistance with transportation for health services, instruction of the subject in the use of telephone or computer to obtain health-related information, and guidance in financial matters that impact general health status in a variety of aspects. Forty-two subject responses reflected these findings. The following are examples identified in the interview data:

“Last week my son called me and told me there was some program about Diabetes that I should watch on cable TV”

“I’m not that good with the computer but he (son) showed me how to get into a medical website where you can ask questions about your health”

“I learned how to e-mail questions to my doctor and his staff … my son showed me how he is a very patient teacher”

“He (son) set up buttons on my ADT security system so I can push a button for emergency medical help, if I need it. It makes me feel secure”

“If I have some unexpected expenses for out of pocket medical or dental care, I contact my son and he helps me manage the payment on my budget”

“When I have a doctor’s appointment my son either goes with me or if I have transportation from a friend here, he will call the doctor after my visit to be sure he knows exactly what the doctor has ordered”

“Even if he can’t go with me my son takes care that I get to the doctor or physical therapy on time. He sometimes sends a taxi to take me”

“I recently bought a supplemental health policy, I asked my son to explain the choices to me. He understands that paperwork”

“I try to make my doctors’ appointments early morning – first thing; then my son can go with me and return to work after he takes me home”

“My son who is a cardiac surgeon … if I need to ask him something then he’ll find the time to call … before I had my heart surgery he explained to me what would happen”

“My son had his personal administrative assistant call me to explain the changes in my healthcare policy coverage”

“I had trouble hearing people on my telephone when they would call but my son arranged for me to get this device that increases the sound level on my telephone. That was great!”

Sons compared favorably with daughters in other areas of health-related social support provided to older mothers, such as in shopping and preparing food. These latter activities may reflect the growing change in domestic skills acquired and culturally accepted from men in contemporary society. There were over 90 data points that evidenced these concerns. The following are examples of the subjects’ responses:

“Well my son … is aware of healthy food. He makes sure that I am not eating eggs or foods high in cholesterol …that’s a big thing with him”

“My son goes grocery shopping once a week, he will often stop by and take me. It is a kind of outing for us both and we discuss my meal plans”

“… he (son) cooks much better than his wife does, so he has been helping me to learn to cook lighter”

“My son told me to use olive oil that it is much better than margarine or butter that everyone here seems to cook with”

“I always call my son when I want to cook for company. He has great suggestions on how to cook healthy”

“My son brings me some fresh fish, usually salmon or tuna, about every two weeks. He tells me I need to include these in my diet”

“I guess when my kids were growing up … you know I made some heavy meals. He (son) tells me that people don’t eat all those carbs anymore”

“He (son) bought me a green pan and showed me how to cook with a bit of vegetable oil-so that is how I prepare most of my meats now”

“He (son) actually bought me a cookbook when he went on his last trip. It is all about cooking vegetables!”

“We have a farm market about an hour from here, I go once or twice a month with my son and he helps me choose fruits and vegetables that are in season”

“His (son’s) business brings him in to town about every two weeks. It’s funny now when he comes over he cooks for me, instead of the other way around. He does a great job and it is always something fresh”

“He (son) brought me an electric grill. It is easier and safer than using my gas broiler and, as he pointed out it is just as healthy for avoiding fat”

Although it was not contained in a specific question on the focused interview guide, the researcher found that there were some data in the form of subjects’ statements, which expressed the subjects’ appreciative feelings toward their sons’ involvement in their health care and health promotion. Twenty-two data points were identified. The following are some illustrations of those data:

‘When I have one of my major Asthma attacks, I call my son first. He is the level-headed one …”

“I thank God for my son, I don’t know how I would figure out all that Medicare paperwork”

“I am very lucky that I have two wonderful sons between the two of them they work it out so one is always available to take me where I need to go”

“I had major surgery last year; it was my eldest son who the doctor spoke with … I knew he (son) would be able to explain my situation to his sisters”

“It was my son who asked to get a second opinion when the doctor told me I needed surgery. I was thankful he thought of it, it didn’t even occur to me”

“I watch my grandchildren once a month or so it is my opportunity to repay my son and his family for all that they do for me. It is a very nice arrangement”

Discussion

The findings of this study support the literature previously cited that suggests sons do contribute to the care of their elderly parents, particularly in the provision of IADL support.10,15–25,28–32 Sex differences in approach to caregiving are only now emerging and are not well understood, as most existing studies have examined only the contrast in type or number of caregiving exchanges between adult children of different sexes. Although not a particular goal of this study, these data also supported the notion that elderly widowed mothers appreciate and are accepting of a variety of supportive attempts from their adult sons. In many exemplar cases, the subjects viewed their sons as better able to deal with the practical issues of their health status and health care needs, when the subject was overcome with the burden of emotional and physical responses to their own condition.

Limitations of the study

The ability to generalize outcomes of this study is limited by its smaller sample size, homogeneity of race, income, and geographic location, as well as the sample selection of convenience.27 The sample population also had a higher than average educational level when compared with the general population in this age cohort.33 However, it does provide early support to the emerging notion in the health-related literature that the roles and contributions of men, especially sons, are underestimated and changing in today’s society.

Recommendations for future research

These findings have several implications for primary care practitioners who work with community-dwelling older widows or older parents, who desire to maintain their independence and self-care. To better understand the complexity of family relationships, it may also be essential to examine the adult children’s point of view with regard to their perceived parental support. A larger more heterogeneous study of adult men with the purpose of describing the perceived nature of their contributions to their aging parents’ health promotion and health maintenance would be in order. Studies of adult sons’ caregiving behaviors need to be conducted in environments in the community that allow direct access to male populations; for example, accessing workplace populations or male-dominated community, civic, or church groups. Additionally, studies of adult sibling units where qualitative contributions are described, and rationales for “best practice” in providing for the needs of aging parents are analyzed in detail, can foster a better understanding of male contributions to parental health-related care. Comprehensive, evidence-based tools that identify descriptors of functions that delineate primary and secondary caregivers, apart from the limitation of ADLs and IADLS, need to be developed. Specific variables that have not been previously well-studied in male caregivers of the elderly, such as perceived burden of care, caregiver self-efficacy, ambivalence as a factor in filial relationships, and family composition, may be added to the data collected from adult male children.28–32,34 An additional link has been identified concerning the concept of “reciprocity” attributing lower morale when older parents are unable to reciprocate exchanges of support to their children. Previous studies have identified a pattern of intergenerational support where the older generation was more likely to receive instrumental forms of social support from their children, while the younger generation was more likely to receive childcare or financial support from their aging parents.35–39 This particular outcome was supported in the findings of the study presented in this paper. In this study, subjects expressed their willingness to care for their young grandchildren when needed, as a way to reciprocate their adult children’s support of them. Longitudinal studies are needed to be initiated now that will identify those dynamic variables that will affect filial relationships within the current generation of growing older “baby-boomers” need to be designed and implemented.

Clinical implications

A goal of this study has been to enhance the extant literature suggesting that while daughters presently continue to emerge as the principle primary care provider of ADL care, there is a significant trend as evidenced in these data for older patients to depend upon sons for a variety of IADLS, particularly when there are no daughters or close female relatives available. As the baby-boomers age, there is more of a cohort trend for families to be smaller, adult daughters to be employed, and for adult children to be more geographically mobile. These factors may combine to make caregivers and health care support networks more limited for the current aging population. It is incumbent upon nurse practitioners, physicians, social workers, and all community health care providers to suggest possibilities for adult sons to participate in the continuing care and improved quality of life outcomes for older parents. While such a broader perspective of resources strengthens the ability of the elderly to live longer in the community, disseminating knowledge of these outcomes might potentially prevent burnout in daughters who may currently assume sole responsibility for the health maintenance and the successful aging of older parents.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The State of Aging and Health in America 2013. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. | |

Administration on Aging [homepage on the Internet]. Health and healthcare. Available from: http://www.aoa.gov/Aging_Statistics/Profile/2013/14.aspx. Accessed July 5, 2014. | |

Fen L, Goldman N, Weinstein M, Yu-Hsuan L, Gorrindo T, Seeman T. Gender differences in adult children’s support. J Marriage Fam. 2003;65:184–200. | |

Franks M, Pierce L, Dwyer J. Expected parent-care involvement of adult children. J Appl Gerontol. 2003;22:104–117. | |

Kim I, Kim C. Patterns of family support and the quality of life of the elderly. Soc Indic Res. 2003;63:437–454. | |

Wang S. Nursing home placement of older parents: an exploration of adult children’s role and responsibilities. Contemp Nurse. 2011;37: 197–203. | |

National Alliance for Caregiving in Collaboration with AARP. Caregiving in the U.S. 2009. NAC and AARP:2009. Available from: http://www.caregiving.org/data/Caregiving_in_the_US_2009_full_report.pdf. Accessed October 13, 2014. | |

Kramer B, Thompson E. Men as Caregivers. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books; 2005. | |

Houde S. Methodological issues in male caregiver research: an integrative review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2002;40:626–640. | |

Del-Pino-Casado R, Frias-Osuna A, Palomino-Moral, P, Martinez- Riera J. Gender differences regarding informal caregivers of older people. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2012;44:349–357. | |

Baker K, Robertson N. Coping with caring for someone with dementia: reviewing the literature about men. Aging Ment Health. 2008;12:413–422. | |

Cho E, Lee N, Kim E, Strumpf N. The impact of informal caregivers on depressive symptoms among older adults receiving formal home health care. Geriatr Nurs. 2011;32:18–28. | |

Yee JL, Schultz RS. Gender differences in psychiatric morbidity among family caregivers: a review and analysis. Gerontologist. 2000;40:147–164. | |

Matthews S. Brothers and parent care an explanation for sons’ underrepresentation. In: Kramer B, Thompson E, editors. Men as Caregivers. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books; 2005:234–249. | |

Hay E, Fingerman K, Lefkowitz E. The worries adult children and their parents experience for one another. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2008;67: 101–127. | |

Parker M, Call V, Dunkle R, Vaitus M. “Out of sight” but not “out of mind”: parent contact and worry among senior ranking male officers in the military who live long distances from parents. Mil Psychol. 2002;14:257–277. | |

Matthews S, Heidorn J. Meeting filial responsibilities in brothers-only sibling groups. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53B:S278–S286. | |

Van Dussen D, Morgan L. Gender and informal caregiving in CCRCs: primary caregivers or support networks. J Women Aging. 2009;21:251–265. | |

Campbell L, Martin-Matthews A. Caring sons: exploring men’s involvement in filial care. Can J Aging. 2000;19:57–79. | |

Miller B, Cafasso L. Gender differences in caregiving: fact or artifact? Gerontologist. 1992;32:498–507. | |

US Department of Health and Human Services [homepage on the Internet]. Measuring the activities of daily living: comparisons across national surveys. Available from: http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/meacmpes.htm. Accessed July 5, 2014. | |

Chao S, Roth P. The experience of Taiwanese women caring for parents-in-law. J Adv Nurs. 2000;31:631–638. | |

Laditka J. Laditka S. Adult children helping older parents. Res Aging. 2001;23:429–456. | |

Lowenstein A, Katz R, Gur-Yaish N. Reciprocity in parent-child exchange and life satisfaction among the elderly: a cross-national perspective. J Soc Issues. 2007;4:865–883. | |

Collins C. The Older Widow-Adult Child relationship as an Influence Upon Health Promoting Behaviors [dissertation]. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America; 2000. | |

Creswell J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. | |

Polit DF, Beck CT. Essentials of Nursing Research: Appraising Evidence for Nursing Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer/ Lippincott/Williams & Wilkens Health; 2013. | |

Fromme EK, Drach LL, Tolle SW, et al. Men as caregivers at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:1167–1175. | |

Gallicchio L, Siddiqi N, Langenberg P, Baumgarten M. Gender differences in burden and depression among informal caregivers of demented elders in the community. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:154–163. | |

Mays G, Lund C. Male caregivers of mentally ill relatives. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 1999;35:19–24. | |

Papastavrou E, Tsangari H, Kalokerinou A, Papacostas S, Sourtzi E. Gender issues in caring for demented relatives. Health Sci J. 2009;3: 41–53. | |

Campbell L. Sons who care: Examining the experience and meaning of filial caregiving for married and never-married sons. Can J Aging. 2010;29:73–84. | |

US Census Bureau. The Older Population: 2010. 2010 Census Briefs. Last modified November 11, 2011. Available from: http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-09.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2014. | |

Peters C, Hooker K, Zvonkovic A. Older parents’ perceptions of ambivalence in relationships with their children. Fam Relat. 2006;55: 539–551. | |

Amirkhanyan A, Wolf D. Parent care and the stress process: findings from panel data. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61B:S248–S255. | |

Coward R, Dwyer J. The association of gender, sibling network composition, and patterns of parent care by adult children. Res Aging. 1990;12:158–181. | |

Merrill D. Caring for Elderly Parents: Juggling Work, Family, and Caregiving in Middle and Working Class Families. Westport, CT: Auburn House; 1997:140–175. | |

Cahill E, Lewis L, Barg F, Bogner H. “You don’t want to burden them”: older adults’ views on family involvement in care. J Fam Nurs. 2009;15:295–317. | |

Crist J. The meaning for elders of receiving family care. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49:485–493. |

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2014 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.