Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 10

Medical school teaching on interprofessional relationships between primary and social care to enhance communication and integration of care – a pilot study

Authors Tahir A , Al-Zubaidy M, Naqvi D , Tarfiee A, Naqvi F, Malik A, Vara S , Meyer E

Received 15 July 2018

Accepted for publication 6 April 2019

Published 28 May 2019 Volume 2019:10 Pages 311—332

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S179833

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Anas Tahir,1,* Mohaimen Al-Zubaidy,1,* Danial Naqvi,1 Ali Tarfiee,1 Falak Naqvi,1 Anam Malik,1 Sarina Vara,2 Edgar Meyer3

1Imperial College School of Medicine, Imperial College, London, UK; 2Faculty of Medicine, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK; 3Imperial College Business School, Imperial College Business School, London, UK

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Background: A pilot study to identify if the delivery of teaching session to medical students would have the potential to enhance communication and a culture of integration between primary and social care, ultimately improving interprofessional relationships between primary and social care. Health and social care integration is a topic of great debate in the developed world and the focus of the upcoming Green Paper by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care in the NHS. There is much uncertainty to how this should be done and is hindered by the various current barriers. The literature identifies that collaborative cultures encourage effective interprofessional relationships and that communication is vital to integration of primary and social care and should be established early in medical training.

Materials and Method: The General Medical Council’s Outcomes for Graduates and Imperial College School of Medicine curriculum were reviewed out to identify outcomes relating to inter-professional relationships between primary and social care. The relevant year group was surveyed to identify if the learning objective was delivered. In order to determine if delivery of a teaching session on nurturing interprofessional relationships between primary and social care would be effective, it was delivered to early clinical years to measure benefits as a pilot study. This was devised of case-based scenarios derived from learning objectives developed with experienced health care professionals. A survey was administered before and after the teaching session to determine if the students felt they had improved with respect to the learning objectives.

Results: The initial survey identified the majority of students found the learning objectives were not delivered. The teaching session found a statistically significant improvement in confidence to nurture interprofessional relationships between primary and social care.

Conclusion: Effective interprofessional relationships between primary and social care, improving communication and collaborative cultures, can be effectively taught in medical school, to improve integration of primary and social care.

Keywords: interprofessional, primary care, social, integration, communication

Introduction

Background

Patients currently experience a broken system where providers do not collaborate, relying on reactive rather than proactive measures to provide care. One solution that has been put forward by the literature and qualitative interviews with general practionioners (GPs) and practice managers (PMs) is the integration of primary health and social care. This is due to the NHS’s increased focus on preventative measures within communities as highlighted in the Five Year Forward View.1

The NHS Confederation argues all population groups would benefit from primary and social care integration.2 Nevertheless, certain demographics remain particularly vulnerable; the elderly population would significantly benefit from better integration due to their susceptibility to long-term conditions.3,4 They are a vital demographic when determining where and how to integrate systems particularity when the UK’s aging population is stretching NHS resources.

Numerous case studies have demonstrated how the integration of care can improve care quality via the Triple Aims: patient experience, clinical outcomes and patient safety.3,4 Moreover, the literature has proven that integration can reduce unnecessary costs and remove non-value steps in the patient journey, commonly accounting for nine times as many activities as value-adding steps.5 In the current economic climate and state of the NHS, this would be a welcome change.

There is much uncertainty regarding how it should be executed, the various currently existing barriers also hinder this. The literature identifies that collaborative cultures encourage effective inter-professional relationships and that communication is the crux to integration of care and should be established early in medical training.6–18 This was supported by the views of GPs and PMs across London, both suggesting the need for educating professionals and in particular students to target the issue from its root cause. This is particularly significant due to the high rate of students entering the GP training pathway. In 2018, Health Education England mandated that at least 50% of medical graduates should enter general practice thus highlighting the importance and wide potential benefit of targeting medical students early on in their training with regards to building the cornerstone of the delivery of integrated care.19

By teaching medical students more about social care medical students can be instilled with the confidence to be able to communicate with and understand the roles of the social care team. A recent study identified the importance of imparting confidence into medical students, who were meeting patients and colleges on the ward for the first time, by demonstrating an improvement in the quality of patient care delivered.20 This is vital in order to overcome the current poor culture and weak collaboration amongst professionals in both teams.

Aims

There are studies highlighting the importance and impact teaching on interprofessional relationships can have on key goals of the NHS, such as integration.21–24 However of these studies, there is not one which assesses this from medical school teaching and recognizes how this can be incorporated into the curriculum. This study is unique as it evaluates the impact of teaching on interprofessional relationships in medical school on communication and integration of care.

It aims to recognize the formal guidelines for teaching around interprofessional relationships to enhance communication and consequently integration of care and determine the shortcomings in a current medical school curriculum. A pilot study aims to determine how to in-cooperate this into the curriculum and to identify the effects of delivery of a teaching session to medical students and its potential to enhance confidence in communication between primary and social care, ultimately improving interprofessional relationships and instilling a positive culture surrounding the importance of integration of the two services.

Methods

GMC outcome for graduates review

The current General Medical Council (GMC) Outcomes for Graduates were reviewed, which outlined a series of expectations for new graduates from university curriculum teaching.25 All learning objectives (LOs) that were related to primary and social care communication were identified, to determine if confident interprofessional communication and relationships were an outcome for graduates.

Reviewing the ICSM (imperial college school of medicine) curriculum

Sofia, the current ICSM interactive curriculum map, allows identification of where and what stage each LO is delivered in the curriculum. In order to determine if the GMC’srelevant outcome for graduates was incorporated into the curriculum, this map was used to identify the current teaching on interprofessional communication, particularly in a primary or social care setting. Sofia’s interface is found in Figure 1. Being a pilot study, the research team opted to select one medical school, Imperial College, London.

| Figure 1 Sofia’s interface.Abbreviation: MBBS, Bachelor of Medicine. |

The following keywords related to communication between primary and social care in the frail and elderly were searched for within the curriculum map:

- Interprofessional Relationships

- Interprofessional communication

- Social care

- Social workers

- Primary care

These LOs were filtered to identify relevant objectives. In order to avoid missing LOs, they were also collated for each year’s clinical communication modules and/or professionalism modules within General Practice (Year 5). These were then assessed for relevance to communication or relationships between primary and social care.

Medical student survey

Given that the relevant LOs were found in the Year 5 curriculum, a student survey for this year group was done to determine if these LOs were taught effectively and understood by students. The survey questions identified answers to the following questions:

- Were you aware of the relevant LO being on the curriculum?

- Is this LO delivered during Year 5 in the context of primary care?

- Would delivery of this LO help to improve your inter-professional communication between primary care and social care?

These questions had set answers of Yes, No or Partially. A further question was asked to determine the best way to deliver this LO. This closed question involved multiple pre-set answers on the survey of tutorial, case-based, problem-based learning, online tutorial, traditional lectures, simulated scenarios and another option (open-ended) requiring written input if the desired answer was not part of the multiple options provided. This survey was approved by Imperial College’s Medical Education Ethical Committee.

Teaching session

Design of teaching session

In order to devise a teaching session to deliver relevant teaching points identified from the GMC’s outcome for graduates, Imperial College’s Curriculum and the student survey results, more specific LOs to educate students were developed from the barriers of integration of primary and social in previous research carried out by the research team in the form of qualitative research and a systematic literature review. It was determined these teaching sessions would not be solely educating students on one barrier, but many of them. For instance, through improving interprofessional communication, culture could be bettered, and goals aligned.

Given the wide domain of social care, the research team determined that social care for the elderly and frail populations would be the focus of the teaching session to ensure a comprehensive and thorough session.

The LOs devised were linked to the barriers and scenarios were then subsequently based on these LOs (Figures 2 and 3). The LOs are as follows:

- To recognize and interpret the various difficulties of interprofessional communication in primary and social care for frail and elderly patients, including the issues surrounding IT systems and funding, lack of awareness of the social sector roles and systems, logistical challenges, lack of regular contact with the social sector, poor perceptions of social care and inefficient multi-disciplinary team (MDT) meetings.26

- To demonstrate the ideal method for interprofessional communication in this setting and population.

- To develop the ability to formulate solutions to overcome the obstacles to improve the logistical challenges of speaking to social and health care for frail and elderly individuals.

- To assess and recognize the role of and importance of social care and workers in the care of frail and elderly individuals.

- To examine the current poor perceptions of social care amongst GPs for the frail and elderly.

| Figure 2 Barriers to communication matched to the learning objectives.Abbreviations: IT, information technology; MDT, multi-disciplinary team; GPs, General Practitioners. |

| Figure 3 Learning objectives matched to the case scenarios.Abbreviations: IT, information technology; MDT, multi-disciplinary team; GPs, General Practitioners. |

The barriers were drawn up in a diagrammatic form and combined together with each other to form each of the five LOs. Each LO targeted different barriers that students would potentially benefit from being taught about.

The participants provided informed consent through the use of an information sheet, and all participants provided written consent to be included within the study.

From these LOs, five case-based scenarios were created. The scenarios were reviewed and altered by several GPs and social carers to ensure realism. The Learning points for each case were drawn up to ensure the relevance of each scenario was upheld. There was also a focus on establishing synergies with other aspects of the medical curriculum touching upon a number of different medical conditions.

An example scenario and learning points are as followed (Figure 4):

| Figure 4 Example scenario.Abbreviations: MDT, multi-disciplinary team; GP, General Practitioner; QOF, Quality and Outcome Framework; GPs, General Practitioners. |

Scenario 2 (Figure 4) draws upon parallels and complements scenario 1 (Appendix A). However, the complex nature of the issue is stressed allowing students to consider that this is not a one size fits all fix; alternative problems are raised in different cases. Furthermore, students are presented with a realistic perspective of how the understaffed NHS runs and potential problems this may cause. The case also touches upon financial incentives that are being used by GPs and may raise discussion as to whether these are perpetuating or solving the problem.

All scenarios, further discussion and learning points for each scenario are found in Appendix A.

Delivery of the teaching session

These interactive discussion-based tutorials lasting 45 mins were taught to 12 Year 2 students, in order to nurture interprofessional relationships at an early stage in their clinical career. The sample size was deemed to be adequate to the research team as having consulted various literature sources.27–30 Students were recruited by a medical faculty member. A senior tutor of Imperial College School of Medicine was present during the tutorial to ensure the LOs were delivered and encouraged the further learning points for each scenario.

The effectiveness of the session was measured by creating questions to identify their confidence in ability at fulfilling each LO. These were delivered before and after the sessions to identify the difference, using a scale of 1–5, with 1 being extremely unconfident and 5 being extremely confident (Figure 5).

| Figure 5 Medical student survey. |

Data collection and statistical analysis following teaching session

In order to determine whether there is a statistically significant improvement between the current level of teaching and the tutorial session, a one-tailed Wilcox Rank Sum Test was carried out. As aforementioned, the participants filled surveys before and after the session. Each filled survey was given an overall mark by adding up the values which participants indicated their surveys, with the minimum and maximum possible total scores being 5 and 25, respectively. The pilot study set out to assess whether the teaching session improves understanding of the set objective; hence, the test was determined to be a one-tailed one. Once these factors had been decided, the following steps were undertaken to analyze the data set.

Results

GMC outcome for graduates review

The importance of interprofessional communication and teamwork, particularly with social care, was highlighted in several areas (Figure 6):

| Figure 6 GMC Outcomes for Graduates review. |

Reviewing the ICSM curriculum

The search results, their interpretations and relevance to the GMC Outcomes for Graduates can be found in Appendix B.

Only the following LO was identified as fully relevant in the Imperial College Curriculum (Table 1):

| Table 1 Learning objectives in the Imperial College Curriculum |

| Table 2 Wilcoxon test results |

Medical student survey

Only 8.2% of Year 5 students (n=73) were aware of such LOs and only 15.1% of students felt that the LOs were delivered within the context of primary care (Question 1 and 2 from the survey) (Figure 7). This indicated that despite the LOs existing, they are not taught, suggesting interprofessional communication between primary and social care is not being targeted effectively in medical school. Additionally, 80.8% of those who responded said better delivery of the LOs would help them improve their interprofessional communication for the future (Question 3 from the survey) (Figure 7). The potential benefits, along with the lack of current delivery of the LOs, identified the need for teaching for these students.

| Figure 7 Student survey results. |

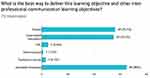

The majority of student felt that a tutorial, case-based scenario and simulated scenario teaching session would be the most effective medium of teaching this LO (Figure 8). This input was incorporated into creation of the teaching session. Simulated scenarios were logistically and financially difficult given the lack of access to funding.

| Figure 8 Student survey results regarding delivery style.Abbreviation: PBL, Problem-based learning. |

Statistical analysis of the teaching session

Pre- and post-surveys based on the LOs were conducted to determine the confidence of students in their knowledge and ability. The score for each question was added up in order to determine the overall score of the survey before and after the teaching session, with the mean score of 15.25 of 25 before, and 19.33 of 25 after. A Wilcox Rank Sum Test was conducted indicating a statistically significant improvement in the students’ confidence in interprofessional communication at the 95% significance level before and after the teaching session (Table 2 and Appendix C). This proved that a teaching session could help improve student perception and understanding of social care and interprofessional communication and relationships.

Discussion

The importance of integration of health and social care in today’s primary health care systems

People don’t want healthcare or social care, they just want the best care. Norman Lamb, Care and Support Minister 2013

The efforts of the health care systems to preserve health have led to an aging population which current frameworks cannot sustain. Governments are searching for ways to deliver quality care to all patients, one possible solution being integration of health care.

Primary health care clinicians are “specialists in generalism”. Primary care physicians create almost a quarter of the doctors in the NHS and play a vital role in providing regular continuity of care at home and in the community, where the majority of patients are managed and treated.31 Given the large role of primary care and the constant interaction with social care providers to offer continuous care in the community, it was a justified option to initially establish this pilot study to improve understanding of and interprofessional relationships with social care for medical students in the context of primary care.

The literature varies regarding the definition of “integration”. In 2001, Gröne and Garcia-Barbero proposed that integration may be defined as bringing “together of inputs, delivery, management and organisation of services as a means of improving access, quality, user satisfaction and efficiency”.32 Arguably, this definition needs updating as care becomes more patient-centered. Integration should be viewed from the patient’s perspective in order to deliver more patient value.33

The UK Government defines integration in line with the “Making it Real” and “National Voices” reports as Person-Centred Coordinated Care:

I can plan my care with people who work together to understand me and my carer(s), allowing me control, and bringing together services to achieve the outcomes important to me. A Narrative for Person-Centred Coordinated Care34

Furthermore, “people and their care needs have evolved but care models have not”.35 The NHS was initially designed to meet routine medical needs and episodic illnesses. Currently, over 26 million people living with a long-term condition in England need to be continuously monitored and treated. Therefore, integration and personalization of care significantly benefits both patients and staff.36 The model of teaching surrounding long-term conditions also must evolve as care models and patient needs do too.

Case studies have demonstrated how the integration of care can improve care quality via the Triple Aims: patient experience, clinical outcomes and patient safety.3,4 As a result of strong population growth and consequent health care demands, cost per capita has continuously increased with a weaker growth in average health care spending. Real health care cost per capita on average increased annually by 0.6% between 2010 and 2016, compared to average spending growth of 5.4% between 1955 and 2010 in the UK.37 Integration can reduce unnecessary costs and remove non-value steps in the patient journey, commonly accounting for nine times as many activities as value-adding steps.20 It is estimated that if all patients saw a primary care provider first for their care in the US, it would save approximately $67 billion annually.38

This highlights the relevance to current health care needs of this pilot study on improving communication and interprofessional relationships and consequently the potential impact on health and social care integration this intends to have. It is thus crucial that medical students recognize how to effectively improve these interprofessional relationships to achieve the synergies of horizontally integrate services between primary and social care.

The pilot study established an improvement in student perception and understanding of social care and interprofessional communication and relationships through teaching. This would translate to improve integration of care, given that the definitions of integration are based on a good relationship between health and social care providers upscaling this project and in cooperation of this in the curriculum of medical schools would encourage the benefits of integrations in today’s health care systems discussed previously.

The curriculum guidance on effective interprofessional communication and working

The UK medical school curriculum is guided by the GMC’s outcome for graduates. This recognizes a series of expectations for new graduates from university curriculum teaching. Several outcomes clearly identify the requirement for new doctors to be able to effectively interprofessional communication and working to encourage care in the best interests of the patient, one aspect of which established previously is integrated care. Examination of the medical school curriculum at Imperial College, London also highlighted these requirements.

However, on surveying the relevant year group in which these learning outcomes were placed, it was apparent that 91.8% of students were not aware of this being part of their curriculum and only 15.1% of students felt it was delivered. The official guidance and curriculum identify and agree with the previous discussion that these qualities should be taught to medical students. However, it is demonstrated that is not taught effectively or signposted. The research team are unaware of any other teaching at other medical schools which highlight the importance of this aspect of the GMC’s outcome for graduates.

Relevance and effectiveness of a teaching session

As a result of the above conclusions and 80.8% of students believing that a teaching session would improve their interprofessional communication and working with social care and consequently the desired outcome for graduates aims, the teaching session was delivered. It found an improvement of student perceptions and understanding of social care and interprofessional communication and relationships, which will thus improve integration of patient care. Given that almost a quarter of the doctors in the NHS are general physicians, a similar proportion of medical students will be directed into a career in primary care. Therefore, the research team recognized primary care to be the most relevant speciality to use to deliver a teaching session within. However, this can be translated to other specialities working with social care and other health care providers, such as nurses. Improving multidisciplinary approaches and working from an early stage in medical careers can further the progression to integration of care and achieving the synergies discussed.

Implications and feasibility of inclusion of this teaching session in the curriculum

Despite the benefits identified of the teaching sessions, it is essential to identify it would feasibly be able to be established for all students. The cost implication and time required of a teaching session to a year group is a major drawback. Financial reimbursement of tutors and finding time in a busy and carefully planned curriculum and year map would be difficult. However, this session was taught by senior medical students, which offers the added benefit of peer teaching. Research highlights the various benefits of peer teaching, including better learning from the students, consolidation for the tutors.39 This would encourage a sustainable model of delivery of this session, particularly at Imperial College, where teaching skills are theoretically and practically taught to Year 5 medical students. If this were to be rolled out as part of the Year 5 Teaching Skills Course, it would allow longitudinal education of the topic, as knowledge learnt in Year 3 would need to be refreshed before teaching it as a Year 5 student. Despite the high effort and initial cost to establish this session, this sustainable model will indirectly improve patient care and costs in the future through better integration of care, although difficult to directly measure.

Limitations and future work

The most significant limitations within this pilot study were the number of sample groups and restriction of the study to Imperial College School of Medicine. However, the future work on this study would involve increasing the number of study groups with different tutors and determining if the apparent significant findings stand. Additionally, this study sets the groundwork for adopting a MDT approach to further potentiate the interprofessional learning within the tutorial setting such as involving trainee social workers and including senior social workers in the running of the sessions. However, unfortunately, this was limited by logistical and funding (discussed below) constraints in this study and is planned to be in-cooperated in future studies. Although the research group deems Imperial College to be broadly representative of medical schools across the UK and to an extent in the developed world, the study would benefit from repeating it in other medical schools with different tutors.

The teaching session was also focussed on the elderly. The research team recognize that mental health and child social care are different and can involve different priorities when discussing inter-professionally. This area of teaching would need to be developed; however, the skills established in the current teaching session would also be applicable and theoretically improve the interprofessional working with doctors and social care providers in different fields of care.

Ideally, a longitudinal study extending beyond graduation of the students would be beneficial to more accurately assess and measure the improvement in interprofessional relationships and communication.

Given the cost implication, it was difficult to access relevant professionals (social workers) to deliver the tutorials. Although their knowledge may not have been as comprehensive, peer teaching by senior students was adopted since this method increases receptiveness as well as other benefits mentioned previously.40 Additionally, the cost restrictions prevented the delivery of the teaching session as simulated case scenarios, which was the most popular delivery method identified by the survey of students. The reimbursement of actors was a cost not able to be covered within the scope of this pilot study. If funding were to be secured, the research team would seek the opportunity to repeat the study and compare the findings to determine if would justify the improvement in the findings, if there were to be any.

Given the success of the pilot study, the research team are currently involved in further establishing this into the curriculum currently with the guidance of a faculty course lead at Imperial College. Further pilot sessions are being run in order to improve the sessions and gaining feedback from students to determine how to improve and at what area to incorporate this into the curriculum. This would produce more reliable results. It is currently planned to be implemented into Imperial College’s Society and Health Module. On establishing this, it is planned to propose this to other medical schools.

Conclusion

Initial findings have drawn interest and they are being presented at the Curriculum Review. The research team have been invited to contribute to the design of the Society and Health Module and its exam and are in the process of applying for Imperial College’s curriculum changing StudentShapers scheme.

To conclude, this pilot study has shown the success of these teaching sessions, which provide scope for implementation into the medical curriculum at Imperial College. This demonstrates the validity of the teaching session to improve interprofessional communication, culture and working in primary and social care and consequently improve integration of care for patients.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in substantial contributions to design, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data and drafting and altering the manuscript. All authors approved of the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in regard to accuracy and integrity of all parts of the study and manuscript. Mr A Tahir and Mr M Al-Zubaidy also lead the research team and all components mentioned above.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1.

2.

3. White J, Sanderson J. Making the case for the personalised approach. NHS Choices; 2018. Available from:

4.

5. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff. 2008;27(3):759–769. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759

6. Lang C, Kern EAM, Schulte T, Hildebrandt H. Integrated diabetes care in germany: triple aim in gesundes kinzigtal. Integr Diabetes Care. 2016;169–184. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-13389-8_10

7. Fillingham D. Can lean save lives? Leadersh Health Serv. 2007;20(4):231–241. doi:10.1108/17511870710829346

8. Wood S, Henderson S. What the system can do: the role of national bodies in realising the value of people and communities in health and care. National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (NESTA); 2016. Available from:

9. Morden A, Jinks C, Ong BN, Porcheret M, Dziedzic KS. Acceptability of a ‘guidebook’ for the management of Osteoarthritis: a qualitative study of patient and clinician’s perspectives. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:427. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-15-427

10. Thomas P. Achieving community oriented integrated care through the 2014 England GP contract. London J Primary Care. 2015;6(3):55–64. doi:10.1080/17571472.2014.11493416

11. Lucas L, Maker J. The state of care in counties. Local Government Information Unit (LGIU); 2015. Available from:

12.

13. Penhale B, Young J. A review of the literature concerning what the public and users of social work services in England think about the conduct and competence of social workers. Professional Standards Authority for Health and Social Care; March, 2015. Available from:

14. Kumar P. Growing older in the UK: a series of expert-authored briefing papers on ageing and health. British Medical Association; September 14, 2016. Available from: .

15. Waterson P. Health information technology and sociotechnical systems: A progress report on recent developments within the UK National Health Service (NHS). Appl Ergon. 2014;45(2):150–161. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2013.07.004

16. Mastellos N, Car J, Majeed A, Aylin P. Using information to deliver safer care: a mixed-methods study exploring general practitioners’ information needs in North West London primary care. J Innovation Health Inf. 2014;22(1):207–213. doi:10.14236/jhi.v22i1.77

17. McDonald A. A long and winding road: improving communication with patients in the NHS. Marie Curie; February, 2016. Available from:

18.

19.

20. Mcnair R, Griffiths L, Reid K, Sloan H. Medical students developing confidence and patient centredness in diverse clinical settings: a longitudinal survey study. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:1. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0689-y

21. Clifton M, Dale C, Bradshaw C. The impact and effectiveness of inter-professional education in primary care: an RCN literature review. Royal College of Nursing’s; February, 2007. Available from:

22. Barwell J, Arnold F, Berry H. How interprofessional learning improves care. Nursing Practice; June 29, 2013. Available from:

23. Olson R, Bialocerkowski A. Interprofessional education in allied health: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2014;48(3):236–246. doi:10.1111/medu.12290

24. Reeves S, Perrier L, Goldman J, Freeth D, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd002213.pub3

25.

26. Osters S, Tiu FS Writing measurable learning outcomes. Director of Student Life Studies; Available from:

27. Julious SA. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharm Stat. 2015;4(4):231–300. doi:10.1002/pst.185

28. Isaac S, Michael WB. Handbook in Research and Evaluation: A Collection of Principles, Methods, and Strategies Useful in the Planning, Design, and Evaluation of Studies in Education and the Behavioral Sciences San Diego. CA: EdITS; 1981. doi:10.1177/105960118200700111

29. Hill R. What sample size is “enough” in internet survey research? Interpersonal Comput Technol. 1998;6(3–4).Available from:

30. Gvan B. Statistical Rules of Thumb. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 2002.

31.

32. Gröne O, Garcia-Barbero M. Integrated care: A position paper of the WHO European office for integrated health care services. Int J Integr Care. 2001;1(e21). doi:10.5334/ijic.28

33. Kodner DL, Spreeuwenberg C. Integrated care: meaning, logic, applications, and implications – a discussion paper. Int J Integr Care. 2002;2. doi:10.5334/ijic.67

34.

35.

36. Sanderson J, White J. Making the case for the personalised approach. NHS England; January, 2018. Available from:

37. Stoye G. UK Health Spending. The Institute for Fiscal Studies; May, 2017. doi:10.1920/bn.ifs.2017.bn0201

38. Spann SJ. Report on financing the new model of family medicine. Ann Family Med. 2004;2(suppl_3). doi:10.1370/afm.237

39. Allikmets S, Vink J. The benefits of peer-led teaching in medical education. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2016;329–330. doi:10.2147/amep.s107776

40. Burgess A, Dornan T, Clarke AJ, Menezes A, Mellis C. Peer tutoring in a medical school: perceptions of tutors and tutees. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:1. doi:10.1186/s12909-016-0589-1

Scenario 1

Mr Smith is a 75-year-old male with poor mobility, due to his arthritis and COPD. Living alone, he is on a care package with four visits a day from the social care team to help with self-care and meals. The GP sends him to hospital because of an infective exacerbation of his COPD. He is admitted to hospital. The social carer is not made aware quick enough resulting in a wasted visit and confusion as to where the patient is.

What are the barriers to interprofessional communication in this case?

Potential discussion points:

Learning points:

● What are common conditions frail and elderly patients live with?

● What are the different conditions requiring different levels of care?

● What types of barriers are brought up in this case?

In this scenario, LO1 one is addressed. It begins by establishing a chronically ill patient with mobility and builds upon this by stressing the importance of the role of the social care team in his care. From here students are able to dwell upon the numerous complexities and barriers of achieving integrated care within the frail elderly population are highlighted. Moreover, students are able to draw upon and apply elements of medical theory with the mention of chronic conditions such as COPD, providing them with a holistic view of elderly care in primary care.

Scenario 2

Recently, a local social care provider has been short staffed due to one of their team members having a medical emergency and another on scheduled annual leave. As a result, the social care team has not been able to attend the weekly MDT meeting for one of the practices they serve. At the same time, the GP practice is finding it very difficult to manage several of their elderly severely diabetic patients, resulting in missing their QOF target with two of these patients having amputations in the last month. The practice manager explains to the GPs at the weekly meeting that the social team can have a significant impact to avoid these types of deterioration in the frail and elderly population’s health.

Potential discussion points:

Learning points:

● What are the reasons why social care is strained?

● Why you need MDT meetings?

● What types of barriers are brought up in this case?

● What are the incentives for health care professionals to meet targets to help patients?

Scenario 2 draws upon parallels and complements scenario 1. However, the complex nature of the issue is stressed allowing students to consider that this is not a one size fits all fix; alternative problems are raised in different cases. Furthermore, students are presented with a realistic perspective of how the understaffed NHS runs and potential problems this may cause. The case also touches upon financial incentives that are being used by GPs and may raise discussion as to whether these are perpetuating or solving the problem.

Scenario 3

Two doctors at a GP practice have met after the afternoon session and one of them says “I just don’t think social teams do any proper work, it’s so hard to even speak to them”. The other doctor thinks of ways to improve the perceptions his colleague has of social workers.

Potential discussion points:

Learning points:

● What does this case show the perception of the GP to be of social teams? Does this resonate with other professions? Do you agree with this?

● What are the best ways to ensure good communication between GPs and social workers?

● What the benefits and disadvantages of these various points?

● Can you relate these to various pilots and why they may not have been successful?

Scenario 3 addresses LO5 by highlighting current poor perceptions of GPs to the social care team. This raises a moral discussion amongst students as to whether its ethical to hold such views. Such thought provoking discussions will address the tribal nature of the NHS from the source which will in turn produce doctors who are more effective and considerate of others roles. LO2 is explored, addressing the pros and cons of different communication methods producing a mindset of efficiency within the students' minds. Finally, this scenario provides scope for further discussion regarding integrated care pilots that currently exist and why they may or may not have worked.

Scenario 4

As explored in the previous scenarios, attending an MDT is not always a viable option, especially for overstretched social care teams. Mr Smith is discharged from hospital and the discharge report expresses a safety concern when he is at home, especially as he is living alone. You, as his GP, are asked to follow-up. Following a call from Mr Smith’s daughter, you are worried he cannot get to the door on time and safely. Rank the following options you have to solve this problem.

Also, What are the roles of social care teams?

Potential answers to discuss benefits and disadvantages:

Learning points:

● What are the barriers here to good communication between GPs and social care teams?

● What are the ways to overcome these obstacles?

● How would you plan if you were to face this unforeseen obstacle as a GP.

● Is there a confidentiality breach risk for Mr Smith?

In this scenario, LO1 is explored once more by allowing students to recognize the complexities and barriers in communication between GPs and the social care team. Students are able to address LO3 by recognizing the variability and unexpected nature of dealing with problems in the NHS. This highlights the need for quick thinking and being able to develop solutions to overcome unforeseen obstacles. Finally, there is much scope for discussion on the positives and negatives of each of the solutions.

Scenario 5:

The GP chooses to ask the receptionists to call the patient. They are unable to get through and the patient suffers a fall. The GP reviews his mistake as part of his personal and professional development in their portfolio. After discussions with his supervisor, it was found that he felt the social workers would not be able to solve the problem quick and well enough. Rank the importance of the activities that the social worker could have done for this patient as a matter of urgency.

What would you do as the GP in this case?

Potential answers to discuss benefits and disadvantages:

Learning points:s

● Did the GP do enough to recognize their mistake? How can they learn from this?

● What roles do the social team have?

● What cannot they do that the GP may not be able to do as well?

Scenario 5 addresses LO5, once again highlighting the poor perceptions of the social care team by GPs. As mentioned this aids in facilitating improved perceptions of medical students from a early age. Furthermore, LO4 is explored by understanding the multifaceted role of the social care team which is often overlooked by GPs. Finally, the scenario touches upon the importance of personal and professional development by stressing the importance of recognizing mistakes and learning from.

Appendix B Review of Imperial curriculum

The search results, their interpretations and relevance to the GMC Outcomes for Graduates are below:

Interprofessional Relationships

|

This search delivered 19 results. The following was found to be partially relevant:

|

Although this LO identifies the difficulty to nurture interprofessional relationships, this is carried out in Year 2, when students have little or no clinical experience, and most definitely more likely to have hospital experience and no official GP or social care experience. This is thus believed to be not targeting interprofessional relationships or practice.

Interprofessional Communication

|

This search delivered 30 results. The following were found to be partially relevant:

|

These LOs identify learning to improve these skills, however, it targets Radiology, palliative care and oncology, not specifically GP, which is a significantly different process and pathway.

However, the General Practice rotation in Year 5 does involve a LO to improve this skill.

|

Social Care

|

This search delivered 16 results. None of these LOs identified teaching to improve communication skills or primary care.

Social Worker

|

This search delivered six results, none of which related to communication or primary care

Primary Care

|

This search delivered 21 results. The following LO was identified.

|

Although this targets the relevant skills, it targets palliative care and oncology, not primary care, which, as mentioned previously, has different pathways and processes.

Each year's clinical communication modules and/or professionalism modules within General Practice (Year 5) were collated. Their significance has been analyzed below:

|

| (Continued). |

| (Continued). |

From this table, it can be identified that there are only 1 LOs relevant for our objectives. This has been identified previously.

Appendix C The Wilcoxn Test results

|

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.