Back to Journals » Advances in Medical Education and Practice » Volume 9

Medical professionalism: perspectives of medical students and residents at Ayder Comprehensive and Specialized Hospital, Mekelle, Ethiopia – a cross-sectional study

Authors Kebede S , Gebremeskel B, Yekoye A, Menlkalew Z, Asrat M , Medhanyie AA

Received 2 February 2018

Accepted for publication 23 May 2018

Published 30 August 2018 Volume 2018:9 Pages 611—616

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S164346

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Md Anwarul Azim Majumder

Seifu Kebede,1 Bisrat Gebremeskel,2 Abere Yekoye,1 Zerihun Menlkalew,1 Mekdes Asrat,1 Araya Abrha Medhanyie3

1Department of Midwifery, Mekelle University, Mekelle, Tigray, Ethiopia; 2Department of Internal Medicine, Mekelle University, Mekelle, Tigray, Ethiopia; 3Department of Public Health, Mekelle University, Mekelle, Tigray, Ethiopia

Background: Different forms of unprofessionalism in terms of lack of respect, preventable medical errors, inability to work together with colleagues, and discrimination while providing service these days can be explained by traditional perceptions of who is a good doctor and who is not.

Objectives: The aim of this study was to determine the perspective of medical students and residents on medical professionalism.

Methods: This was a cross-sectional study. A validated tool has been used to collect data from 276 participants. SPSS version 23 has been used to analyze and summarize data.

Results: Only 30% of respondents were females and the rest were males. The overall mean score of professionalism was 174.96 out of 220. There was no significant difference between male and female respondents. However, students from a different phase of the study were significantly different in some of the core elements of professionalism. The role model was indicated as one way of learning professionalism.

Conclusion and implication: The overall level of professionalism was observed to be positive. However, medical education should focus on the core elements of medical professionalism through the teaching and learning process. Medical teachers should also focus on being role models for their students as students consider them to be a means for learning the qualities of professionalism. The teaching institution could strengthen efforts through locating and recognizing professional faculty members who can be effective role models.

Keywords: professionalism, medical students, residents, Ayder, perspective, Tigray

Background

Thinking of medicine’s indenture with humanity, professionalism is its foundation. This is why it has been said that physicians need a high standard of performance that safeguards use of core issues of professionalism.1

However, defining professionalism in this constantly evolving world is not easy.2 When it comes to medical professionalism it gets tougher to create common and clear understanding. Different scholars have defined medical professionalism differently.

In the past, medical professionalism has been considered as the ability of a doctor in putting the interest of the patient before himself.3 Traditionally, the growth of professionalism trusted on inherent learning from role model professionals. It has also been indicated that to create more holistic and rational doctors, there should be the urgency of creating more role model professionals.1

The medical profession is one of the most evolving professions by its nature. So is medical professionalism.4 Medical professionalism is evolving from autonomy to accountability, from expert opinion to evidence-based medicine, and from self-interest to teamwork and shared responsibility.5 By the process of exploration and reflection, we can see medical professionalism evolving from paternalism to partnership with patient and family, from tribalism to collegiality, and from self-sacrifice to shared responsibility.2

It should be noted that relying on the inherent learning from role model professionals neglects the socioeconomic background variability of the students. With different backgrounds, it is clear that there will also be a difference in the perception of what is professional and not-professional. That is why researchers are insisting on the principle that states that professionalism should be “taught” besides being “caught” from the role models.6–8

It has been indicated that medical professionalism is poorly understood. If we can agree on medical professionalism as an important academic issue, we can surely agree about it being a “hot” issue. This is why medical professionalism is receiving global interest these days due to high-profile failures in the profession mainly because of unprofessionalism.6–10

Studies clearly show that students with inappropriate behavior during their study tenure are more likely to be accused of unprofessionalism by monitoring bodies of the hospitals.11 Professionalism with high moral characters should be developed from the schooling time of medical students.8

Medical schools have taught the theoretical and technical aspects of medicine for a long time. Due to these determining factors, medical staff have been admired because of their theoretical and technical expertise; so, abrasive behaviors are not usually a challenge for success.12

Different forms of unprofessionalism explained by lack of respect, preventable medical errors, inability to work with colleagues, and discrimination while providing service these days can be explained by traditional perceptions of who is a good doctor and who is not.

In various articles, students have reported that there was no opportunity for them to learn about professionalism. They also reported that there are very few role models to follow.13 This is the vital reason for scholars to insist that assessing the professionalism level of medical students in their schooling time is one of the most acknowledged strategies to combat the challenge that modern medicine is facing in recent years.14 As a result, we conducted this research in order to determine the perspectives of medical students and residents at Ayder Comprehensive and Specialized Hospital on medical professionalism.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study conducted on medical students and residents of Mekelle University, at Ayder Comprehensive and Specialized Hospital. The study population comprised clinical I (C-I), clinical II (C-II), interns and resident students of the academic year of 2016/2017. The sample size was calculated as 308 students using sample size calculation. Stratified and convenience sampling techniques were used to select the study participants.

Data were collected using a validated instrument,15–17 which consists of nine core elements of professionalism including honesty, responsibility, accountability, confidentiality, respectfulness, compassion, communication, maturity, and self-directed learning. There was a range of statements under each core element of professionalism that was measured by the 5-point Likert scale, giving a maximum score of 220.

The mean score of all nine attributes of professionalism represented the professionalism of the respondents as a whole. The instrument also contained four open-ended questions to explore participants, opinion on what professionalism meant to them, how professionalism should be taught, how they learned professionalism, and how professionalism should be assessed. Then, the data were compiled and analyzed using SPSS version 23 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethical approval was provided by the research review board of Mekelle University, College of Health Sciences. Participants signed a written informed consent form for participation. No questions that could reveal the participants’ identity were asked.

Results

Out of 308 questionnaires, 276 were filled and returned with a response rate of 90%. In all, 72.1% respondents were male and the rest were female. The mean of the cumulative grade point average was 3.1±1. Out of the respondents, 96 (34.5%), 73 (26.4%), 68 (24.6%), and 39 (14.1%) were C-I, C-II, interns, and residents, respectively. The mean age of the study participants was 24.91 (2.7 SD) years.

A majority (34%) of male respondents were from the C-I batch while residents constituted the least (15%) number of male respondents. Similarly, the highest proportion (38%) of female respondents was from C-I and their proportion was the least (13%) at the level of residents.

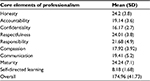

The overall mean score of professionalism in this study was 174.96±41.73. Regarding each element of professionalism, the total mean score is demonstrated in Table 1.

| Table 1 Mean scores of professionalism of medical students and residents of Ayder Comprehensive and Specialized Hospital, Mekelle city, Ethiopia, 2017 (n=276) |

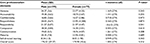

The overall mean score of professionalism for female respondents was 170.90±45.6 while it was 176.53±29.37 for male participants with no statistically significance differences (P=0.316). Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference observed in the mean score of the core elements of professionalism between female and male participants (Table 2).

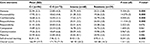

Total score of professionalism with respect to the batch of respondents was 169.99±19.68, 171.75±71.99, 181.90±28.22, and 181.08±41.73 for C-I, C-II, interns, and residents, respectively. Among the nine core elements of professionalism, a statistically significant difference was observed in honesty, accountability, confidentiality, and respectfulness among C-I, C-II, interns, and residents (Table 3).

The last component of the questionnaire consisted of four open-ended questions aimed at assessing the opinions of participants (Table 4). The first question was “what do you mean by professionalism?”; 34% of the participants answered with a confident and positive approach to the profession while 36% of them responded skillfully.

| Table 4 Participants’ opinions through open-ended questions Note: Others, unrelated answers which were not important to report. |

The second question was “how professionalism should be taught?”; 35% of the respondents considered experience as the answer. Role models as a means for teaching professionalism were picked by 20% of the participants. The third question was “how do you learn professionalism?”; 31% of them said they learned professionalism from experience while 29% of the respondents’ response was role models. The last question was “how professionalism should be assessed?”; participants reacted to the questions according to their opinion (Table 4).

Discussion

Sir Williams, one of the four founders of John Hopkins Hospitals, once said “good doctors treat diseases and great doctors treat a person with the disease.” This sentence clearly explained that medical professionalism is not only about clinical competency but also, if not most importantly, holistic care provision including compassion and empathy.

If we have to provide quality health care, doctors need to be professional. Studies provided evidence that the level of comfort a patient gets from the holistic care of physicians is considerably important for disease progression. There is an Ethiopian proverb which states “the facial expressions of the waiters is more important than the taste of the food they bring.” Most of the time it is the approach that matters more than the service itself. Hence, physicians are highly expected to possess the core elements of professionalism alongside scientific knowledge and clinical skills.

This study was about the medical students and residents of ASH. The response rate was 90%, which is similar to other studies.16,18 The number of female participants was lower than their male counterparts. This is also the case in studies conducted in other countries.15,16 In contrast, a study done in Bangladesh had female participants outweighing their male counterparts.17 But considerably lower than the other study conducted in Malaysia.16

The present study found that the total mean score of professionalism is 175.96±41.73. This is similar to evidence from a comparative study between Malaysian medical students (175.50±13.70) and Bangladesh medical students (177.14±13.35).17

In terms of core values of professionalism like honesty, accountability, compassion, and self-directed learning, several studies reported that female and male results differ significantly.15,19 Contradictory to this, the current study found that the professionalism level between male and female participants was not significantly different (Table 2). This is may be due to the sociocultural similarities across the study participants. Even though it was not statistically significant, male participants scored a higher overall mean score of professionalism (176.53) than their female counterparts (170.90). It is not easy to explain why males score higher than females, but female participants in this study are less than half of the male respondents. This may influence the results because the disproportion between the two sexes will affect the result.

The level of professionalism in this study has been significantly associated with the phase of the study (Table 3). This finding is in line with a study conducted in the USA.19 However, other studies found insignificant differences across various phases of studies.15 Studies concluded that the level of professionalism declines as the years of study increase.15–21 Similarly, in this study intern medical students scored a significantly higher level of professionalism than residents. This can be explained as a result of the strict expectation the department has from medical intern students.

Among the participants of this study, 36% considered a skillful approach as professionalism. This number is very low when compared to other research conducted in Malaysia reporting 67%.17 Medical teachers must focus on this as most of the students do not have a good understanding of medical professionalism. Or maybe this result can be explained as the difficulty to explain and define professionalism. Either way, educators and medical teachers need to emphasize a clear understanding of professionalism and help their students identify the elements of professionalism. A clear document from the institutions should be provided so that faculty members have more or less similar understanding about professionalism for them to impart knowledge similarly.

Regarding how professionalism should be taught, 35% and 20% of the participants thought professionalism should be taught through experience and role models, respectively, while 23% picked formal education as a teaching strategy for professionalism. This finding is more or less similar to other studies.15,16 Role models are one of the sources of professionalism for students to look up to. Most studies supported this argument.21,22 However, in the current study, only 20% of participants favored role models as a means of teaching professionalism. It is important to also note that 23% favored formal education as a method of teaching professionalism. Thus, departments and units should consider the variability of preferred ways of teaching medical professionalism and try to sensitize the faculty members accordingly.

In this study, 31% of the participants believed that they learned professionalism through everyday experience while 29% and 15% gave the credit to role models and formal education, respectively. We note that role models are less preferred in terms of learning professionalism from. This finding is similar to a previous study.17 In contrast, various researchers insist on role models as a means of learning professionalism.15,22,23

In terms of professionalism assessment, 30% of medical students and residents of ASH who participated in the study indicated job performance assessment to determine the level of professionalism, while feedback and formal education assessment was favored by 25% of them. This is in contrast with a previous study in which only 3% of the respondents considered formal education to assess professionalism.16

Looking at the responses to open-ended questions, in average, about 16.75% and 14% of participants favored “others” and “not responded”, respectively. “Others” implied responses which were irrelevant and could not be categorized. It is obvious that the medical students and residents at ASH are hesitant and not committed to responding to all open-ended questions. This evidence is also a case of previous studies.15–17 However, the findings of this study will hopefully contribute to the improvements of the quality of medical education at Ayder Specialized Hospital and the production of competent and compassionate medical doctors.

Conclusion and recommendation

The level of professionalism among medical students and residents in this study is observed to be positive. There was no significant difference between female and male respondents. However, the core elements of professionalism have been found to be significantly different among different phases of the study.

Medical education involves the system by which we produce medical doctors. An unprofessional medical student will remain an unprofessional medical doctor after graduation. Alongside designing and developing the scientific contents necessary for developing the skills to be a doctor, medical education should also focus on sensitizing and producing professional doctors.

During their classroom and clinical teaching sessions, medical teachers should also focus on the basic principles and core elements of medical professionalism. Moreover, teachers are supposed to consider their skills, attitudes, and behaviors in a way in which they could influence their students and be role models, for role modeling is one of the students’ perceptions of learning about medical professionalism. Teaching institutions can play a vital role by recognizing and awarding role model teachers so that students will be able to look up to those individuals and identify the qualities that they should possess in their future medical practices as professional doctors.

Availability sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from SK.

Acknowledgments

The source of funding for this research was Mekelle University through its annual budget for research capacity building for its faculty members. We thank Mekelle University for funding the research and study participants for their time and attention throughout the study.

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Zink T, Halaas GW, Brooks KD. Learning professionalism during the third year of medical school in a 9-month-clinical rotation in rural Minnesota. Med Teach. 2009;31(11):1001–1006. | ||

Young CE. Medical professionalism in the 21st century. Tenn Med. 2013;106(8):5,40. | ||

Yarmolinsky A. Professionalism vs commercialism in managed care: the need for a national council on medical care. JAMA. 1997;278(1):21–22. | ||

Woodruff JN, Angelos P, Valaitis S. Medical professionalism: one size fits all? Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51(4):525–534. | ||

Wynia MK, Papadakis MA, Sullivan WM, Hafferty FW. More than a list of values and desired behaviors: a foundational understanding of medical professionalism. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):712–714. | ||

Wynia MK, Latham SR, Kao AC, Berg JW, Emanuel LL. Medical professionalism in society. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(21):1612–1616. | ||

Wynia MK. The short history and tenuous future of medical professionalism: the erosion of medicine’s social contract. Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51(4):565–578. | ||

Whitcomb ME. Medical professionalism: can it be taught? Acad Med. 2005;80(10):883–884. | ||

Woollard KV. Medical professionalism project. Med J Aust. 2003; 178(2):93–94; author reply 94–95. | ||

Will E. Extending medical professionalism. J R Soc Med. 2011; 104(4):144. | ||

West CP, Huntington JL, Huschka MM, et al. A prospective study of the relationship between medical knowledge and professionalism among internal medicine residents. Acad Med. 2007;82(6):587–592. | ||

Wearn A, Wilson H, Hawken SJ, Child S, Mitchell CJ. In search of professionalism: implications for medical education. N Z Med J. 2010;123(1314):123–132. | ||

Wagner P, Hendrich J, Moseley G, Hudson V. Defining medical professionalism: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 2007;41(3):288–294. | ||

Varga-Atkins T, Dangerfield P, Brigden D. Developing professionalism through the use of wikis: a study with first-year undergraduate medical students. Med Teach. 2010;32(10):824–829. | ||

Salam A, Yousuf R, Md Islam Z, et al. Professionalism of future medical professionals in Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin, Malaysia. Bangladesh J Pharmacol. 2013;8(2):124–130. | ||

Haque M, Zulkifli Z, Haque SZ, et al. Professionalism perspectives among medical students of a novel medical graduate school in Malaysia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2016;7:407–422. | ||

Islam Z, Salam A, Hellali AM, et al. Comparative study of professionalism of future medical doctors between Malaysia and Bangladesh. J Appl Pharmaceutical Sci. 2014;4(4):66–71. | ||

Kongsved SM, Basnov M, Holm-Christensen K, Hjollund NH. Response rate and completeness of questionnaires: a randomized study of Internet versus paper-and-pencil versions. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9(3):e25. | ||

Nath C, Schmidt R, Gunel E. Perceptions of professionalism vary most with educational rank and age. J Dent Educ. 2006;70(8):825–834. | ||

Duke LJ, Kennedy WK, McDuffie CH, Miller MS, Sheffield MC, Chisholm MA. Student attitudes, values, and beliefs regarding professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(5):104. | ||

Brown ER. Exporting medical education: professionalism, modernization and imperialism. Soc Sci Med Med Psychol Med Sociol. 1979;13A(6):585–595. | ||

Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Understanding medical professionalism: a plea for an inclusive and integrated approach. Med Educ. 2008;42(8):755–757. | ||

Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Medical professionalism in society. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(17):1288–1289. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.