Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 11

Mediating effects of perceived stress on the relationship of positivity with negative and positive affect

Authors Horiuchi S , Tsuda A , Yoneda K , Aoki S

Received 6 February 2018

Accepted for publication 20 April 2018

Published 2 August 2018 Volume 2018:11 Pages 299—303

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S164761

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Satoshi Horiuchi,1 Akira Tsuda,2 Kenichiro Yoneda,3 Shuntaro Aoki4,5

1Faculty of Social Welfare, Iwate Prefectural University, Iwate, Japan; 2Department of Psychology, Kurume University, Fukuoka, Japan; 3Graduate School of Psychology, Kurume University, Fukuoka, Japan; 4Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Tokyo, Japan; 5Graduate School of Psychological Science, Health Sciences University of Hokkaido, Hokkaido, Japan

Background: Positivity refers to “a general tendency to view life and experiences with a positive outlook”. Enhanced positivity has been linked with decreased negative affect and increased positive affect, but rather little is known about the factors that mediate these relationships. One potential such factor is perceived stress, which refers to how one appraises life situations as stressful. This study examined the mediating effects of perceived stress on the associations of positivity with negative and positive affect. Two hypotheses were tested: 1) positivity is negatively associated with perceived stress, which in turn is positively associated with negative affect, and 2) positivity is negatively associated with perceived stress, which in turn is negatively associated with positive affect.

Methods: An online survey was conducted with 100 Japanese men and 100 Japanese women who were members of a survey company in January 2018. They completed questionnaires on positivity, perceived stress, and negative and positive affect. All survey procedures were managed and conducted by a web-survey company.

Results: Mediation analyses indicated that perceived stress was a mediator in the relationship between positivity and negative affect. Perceived stress was also found to be a mediator in the relationship between positivity and positive affect.

Conclusion: Positivity was found to be associated with negative affect and positive affect via perceived stress.

Keywords: positivity, perceived stress, negative affect, positive affect, positive orientation

Introduction

Positive psychologists have paid considerable attention to the identification of predictors of optimal human functioning, such as well-being.1 Positivity, also called positive orientation,2 refers to “a general tendency to view life and experiences with a positive outlook.”3 It represents one construct closely related to optimal human functioning.4 Positivity is a common component of self-esteem, life satisfaction, and optimism.5 Enhanced positivity has been linked with better affective well-being, including decreased negative affect and increased positive affect.2,4 For example, Caprara et al3 reported that individuals with higher levels of positivity showed lower levels of negative affect and higher levels of positive affect. However, little is known about the mediating factors underlying these relationships.

One potential mediating variable is perceived stress. Stress was defined by Lazarus and Folkman6 as a psychological or behavioral response to events appraised as threatening and for which people lack sufficient resources to cope. Perceived stress, then, refers to the extent to which certain life situations are appraised as stressful.7 Conceptually, positivity is related to perceived stress. The theory of positive orientation suggests that positivity facilitates adaptation to stressors by promoting the use of effective coping strategies,2,8 which suggests that enhanced positivity is related to reduced perceived stress by facilitating the use of effective coping strategies. In addition, Atanes et al9 found that perceived stress was positively associated with negative affect and negatively associated with positive affect. None of these studies considered all these relationships simultaneously.2,4,9 More specifically, no study has yet directly tested whether perceived stress mediates the associations of positivity with negative and positive affect. By measuring these three variables simultaneously and performing mediation analyses, possible mediation effects of perceived stress can be tested directly.

It would be important to examine mediating effects for the following two reasons. First, it could deepen our understanding of how positivity relates to affective well-being. This could in turn exclude the possibility that previously observed correlations between positivity and affective well-being are merely superficial. Second, it can also provide useful information for practitioners interested in stress management or affective well-being enhancement. If perceived stress does show a mediating effect, it would suggest that positivity can reduce perceived stress, which in turn could decrease negative affect and improve positive affect. This suggestion might serve as a conceptual framework for positivity interventions aimed at managing stress and enhancing affective well-being.

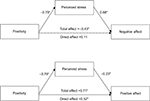

This study examined the mediating effects of perceived stress on the associations of positivity with negative affect and positive affect. Specifically, we tested the following two hypotheses: 1) positivity is negatively associated with perceived stress, which in turn is positively associated with negative affect, and 2) positivity is negatively associated with perceived stress, which in turn is negatively associated with positive affect (Figure 1).

| Figure 1 Hypothetical mediation models of the relationships between positivity (independent variable), perceived stress (mediator), and negative affect (upper) and positive affect (lower) (outcomes). |

Materials and methods

Participants

This online survey was conducted in January 2018. All survey procedures were managed and conducted by a web-survey company. Each participant first gave informed written consent before they completed the questionnaires. The study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of Kurume University (no 296). A total of 200 men and women participated in this study. The sample size was determined by the research budget. Of the participants, 50.0% (n=100) were male, and participants had the following age distribution: 0.5% (n=1) aged 10–19 years, 11.5% (n=23) in their 20s, 25.5% (n=51) in their 30s, 29.5% (n=59) in their 40s, 24.5% (n=49) in their 50s, 6.0% (n=12) in their 60s, and 2.5% (n=5) in their 70s or older.

Measurement tools

Positivity

Positivity was assessed using the Japanese version of the Positivity Scale.3 This is a single-factor scale with 8 items, each of which is rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). It has been found to be reliable and valid.3 The score on one reversely worded item was reversed. The total score is the sum of the eight-item scores; higher scores indicate a higher level of positivity.

Perceived stress

Perceived stress was measured using the Japanese version of the Perceived Stress Scale.10 This single-factor scale contains 14 items and measures the degree to which individuals appraise certain life situations as stressful over the past month. Each participant is rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). It has been found to be reliable and valid.10 The scores on the seven reversely worded items were reversed. The total score is the sum of the 14 item scores, and higher scores indicate a higher level of perceived stress.

Negative and positive affect

Negative and positive affect were assessed using the Japanese version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule.11 This scale comprises two factors, negative affect and positive affect, each with 8 items, and measures how frequently each participant experienced these types of affect over the past month. Each item is rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 6 (very often). The scale has been found to be reliable and valid.11 The scores of the 8 items in each factor are summed to create the total score, and higher scores indicate higher negative or positive affect.

Procedure

The participants received thorough explanations of the study purpose and procedure, possible publication of the results following data analysis, their rights as participants (eg, the right to refuse to participate or withdraw their participation at any time without penalty), and the voluntary nature of participation. Informed consent was obtained before the participants began the questionnaires.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 23 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA; SPSS 2.16) and the PROCESS macro (version 2.16) were used for the analyses. Two mediation analyses were conducted to test the hypotheses. In the first analysis, negative affect was set as the dependent variable, while positive affect was set as the dependent variable in the second analysis. In both, positivity was the independent variable and perceived stress the mediating variable. Mediating effects were considered to have been demonstrated if the following 4 conditions were fulfilled: 1) there was a significant indirect effect of perceived stress; 2) there was a significant total effect, whereby there was a significant effect of positivity on the dependent variable occurred without controlling for the effect of the mediator on the dependent variable; 3) relative to the total effect observed in (2), there was a smaller direct effect of positivity on the dependent variable after controlling for the effect of the mediator on the dependent variable; and 4) positivity had a significant effect on perceived stress (the mediating variable).12 The significance of the indirect effect of perceived stress was evaluated based on the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval (BCCI) during the bias-corrected bootstrapping analysis. If the interval did not include zero, it was considered to be significant. The resampling size was k =5,000, which was determined based on the procedures of previous studies.13,14

Results

Descriptive analyses

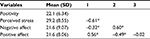

Table 1 shows the mean and standard deviation of all variables, as well as the correlations between the variables.

| Table 1 Mean SD and Pearson’s correlations among the studied variables (n=200) Note: *p<0.01. (1) Positivity; (2) perceived stress; (3) negative effects. Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation. |

Tests of hypotheses

First hypothesis

The results of the mediation analysis with positivity as the independent variable, negative affect as the dependent variable, and perceived stress as the mediating variable are shown in Figure 2. The estimates were standardized. The indirect effect of perceived stress was significant (estimate = –0.54, BCCI [–0.73, –0.38]), as was the total effect of positivity on negative affect (estimate = –0.43, 95% confidence interval (CI) [–0.63, –0.24], p<0.01). The direct effect of positivity on negative affect (estimate =0.11, 95% CI [–0.10, 0.31], p=0.30) was smaller than was the total effect. The effect of positivity on perceived stress was also significant (estimate = –0.79, 95% CI [–0.95, –0.64], p<0.01). Therefore, perceived stress was found to mediate the relationship between positivity and negative affect.

Second hypothesis

The results of the mediation analysis with positivity as the independent variable, positive affect as the dependent variable, and perceived stress as the mediating variable are shown in Figure 2. The indirect effect of perceived stress on positive affect was significant (estimate =0.18, BCCI [0.08, 0.30]), as was the total effect of positivity on positive affect (estimate =0.71, 95% CI [0.56, 0.86], p<0.01). The direct effect of positivity on positive affect (estimate =0.52, 95% CI [0.34, 0.71], p<0.01) was smaller than was the total effect. The effect of positivity on perceived stress was also significant (estimate = –0.79, 95% CI [–0.95, –0.64], p<0.01). Therefore, perceived stress was found to mediate the relationship between positivity and positive affect.

Discussion

This study examined whether associations of positivity with negative and positive affect would be mediated by perceived stress. The first hypothesis – that positivity is negatively associated with perceived stress, which in turn is positively associated with negative affect – was supported. The second hypothesis – that positivity is negatively associated with perceived stress, which in turn is negatively associated with positive affect – was also supported. Therefore, perceived stress seems to act as a mediator for the associations of positivity with negative affect and positive affect. Previous studies did not examine positivity, perceived stress, and affect simultaneously, which made it difficult to discount the possibility that the correlations among them were superficial. By providing a framework for these relationships, we have deepened our understanding of how positivity relates to affective well-being.

This study enhances the possibility that positivity is a correlate of negative affect and positive affect by clarifying perceived stress as a mediator of these relationships. More pressingly, however, we must identify the predictors of well-being in positive psychology, rather than mere correlates. The cross-sectional nature of this study provides the rationale for conducting a longitudinal or experimental study examining the associations among positivity, perceived stress, and affect. This limitation is important because the mediating effects observed in cross-sectional studies are not necessarily replicated in longitudinal research.15

Another limitation is that the sample included Japanese members of a web-survey company, and was not representative of Japanese people. The sample size was also not determined based on a priori power analysis. Therefore, it is important to replicate the current findings with larger and more diverse samples. However, this study provided the first evidence on the mediating effects of perceived stress on the associations of positivity with negative and positive affect. Managing stress represents an important public health concern in Japan.16 The present findings provide a rationale to conduct a further study on the mediating roles of perceived stress in a more representative sample of Japanese people. Such a study can further increase our understanding on how Japanese people manage stress and affect.

Interestingly, the full mediation effect was found in the model with negative affect, but only partial mediation was found in the model with positive affect. It is difficult to explain why these differences were found. However, these differences suggest that positivity affects negative and positive affect in various ways. Further exploration of these differences will increase our understanding of the mechanisms involved in positivity and its effects on affect.

The finding that perceived stress mediates the relationships of positivity with negative affect and positive affect could provide useful information for mental health professionals and stress management interventionists. Specifically, enhancing positivity might help decrease perceived stress, thereby reducing negative affect and enhancing positive affect. Therefore, positive psychological interventions focusing on positivity have the potential to reduce negative affect and to enhance positive affect. The findings of this study provide a rationale to conduct such interventions to help people manage stress and affect.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI, grant number 15H03459.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Milioni M, Alessandri G, Eisenberg N, Caprara GV. The role of positivity as predictor of ego-resiliency from adolescence to young adulthood. Pers Individ Differ. 2016;101:306–311. | ||

Alessandri G, Caprara GV, Tisak J. Further explorations on the unique contribution of positive orientation to optimal functioning. Eur Psychol. 2012;17(1):44–54. | ||

Caprara GV, Alessandri G, Eisenberg N, et al. The positivity scale. Psychol Assess. 2012;24(3):701–712. | ||

Caprara GV, Eisenberg N, Alessandri G. Positivity: the dispositional basis of happiness. J Happiness Stud. 2017;18(2):353–371. | ||

Caprara GV, Fagnani C, Alessandri G, et al. Human optimal functioning: the genetics of positive orientation towards self, life, and the future. Behav Genet. 2009;39(3):277–284. | ||

Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer; 1984. | ||

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(3):385–396. | ||

Caprara GV, Steca P, Alessandri G, Abela JRZ, McWhinnie CM. Positive orientation: explorations on what is common to life satisfaction, self-esteem, and optimism. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2010;19(1):63–71. | ||

Atanes AC, Andreoni S, Hirayama MS, et al. Mindfulness, perceived stress, and subjective well-being: a correlational study in primary care health professionals. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:33. | ||

Sumi K. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Perceived Stress Scale. Jpn J Health Psychol. 2006;19(2):44–53. | ||

Sato A, Yasuda A. Development of the Japanese version of Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) scales. Jpn J Pers. 2000;9(2):138–139. | ||

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. | ||

Horiuchi S, Tsuda A, Aoki S, Yoneda K, Sawaguchi Y. Coping as a mediator of the relationship between stress mindset and psychological stress response: a pilot study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2018;11:47–54. | ||

Takagaki K, Okamoto Y, Jinnin R, et al. Mechanisms of behavioral activation for late adolescents: positive reinforcement mediate the relationship between activation and depressive symptoms from pre-treatment to post-treatment. J Affect Disord. 2016;204:70–73. | ||

Maxwell SE, Cole DA, Mitchell MA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation: partial and complete mediation under an autoregressive model. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(5):816–841. | ||

Horiuchi S, Tsuda A, Kobayashi H, Prochaska JM. Reliability and validity of the Japanese language version of Pro-Change’s decisional balance measure for effective stress management. Jpn Psychol Res. 2012:54(2):128–136. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.