Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 15

Maternal Satisfaction and Factors Associated with Institutional Delivery Care in Central Ethiopia: a Mixed Study

Authors Debela AB, Mekuria M , Kolola T , Bala ET , Deriba BS

Received 16 December 2020

Accepted for publication 8 February 2021

Published 19 February 2021 Volume 2021:15 Pages 387—398

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S297662

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Ayinalem Berhanu Debela,1 Mulugeta Mekuria,2 Tufa Kolola,2 Elias Teferi Bala,2 Berhanu Senbeta Deriba3

1Adea Berga Health Office, Oromia Regional Health Bureau, Enchini, Ethiopia; 2Department of Public Health, Ambo University College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ambo, Ethiopia; 3Salale University College of Health Sciences Department of Public Health, Fitche, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Berhanu Senbeta Deriba Email [email protected]

Background: Women satisfaction recognized as an important outcome of the maternal health care delivery system. Despite the Ethiopian federal ministry of health implemented compassionate, respectful, and caring as one of the health sector transformation agendas to increase health service utilization, the level of maternal satisfaction of institutional delivery is still low. This study aimed to assess maternal satisfaction and factors associated with institutional delivery care in central Ethiopia.

Methods: Community-based cross-sectional study, which involved quantitative study supplemented with qualitative methods were employed. Mothers were proportionally allocated to each selected kebele according to the number of their size. Data were collected by a face-to-face interview using a standardized questionnaire to determine the level of maternal satisfaction with birth care. The result was presented using texts, percentages, and tables. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regressions were performed between dependent and independent variables at 95% confidence intervals and a P-value < 0.05 to show a significant association. In the qualitative part, data were transcribed carefully and analyzed thematically.

Results: The overall a total of 451 respondents participated in this study making a response rate of 98%. The level of maternal satisfaction was 36.6% in this study. Spontaneous vaginal deliveries (SVD) (AOR: 7.33, CI: 2, 26.79), being attended by female sex health workers (AOR: 1.54, CI: 1.04, 2.28), receiving ambulance service to arrive at health facilities (AOR: 7.84, CI: 2, 61.63), utilizing of maternal waiting areas AOR: 1.72, CI: 1.09, 2.66), and respectful care (AOR=1.55, CI: 1.03, 2.34) were factors associated with maternal satisfaction. From qualitative study, three themes and ten categories have emerged.

Conclusion: Maternal satisfaction towards the delivery service was low. SVD, being attended by female sex health workers, ambulance service, cleaned delivery room, and respectful care were factors associated with maternal satisfaction. The health facilities in the study areas need to work on improving health facility cleanliness, health workers’ compassionate and respectful care, and providing ambulance service as a main means of transportation for laboring mothers.

Keywords: care, delivery, labor, maternal satisfaction, services

Background

Maternal satisfaction with delivery service is a means of secondary prevention of maternal mortality, since satisfied women may be more likely to adhere to health providers’ recommendations.1 World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the assessment of women’s satisfaction to improve the quality and effectiveness of health care and also promotes skilled attendance at every birth to reduce maternal mortality.2–4 Satisfaction is directly related to the utilization of service and the perception of the outcome of care that meets clients’ expectations.2 In recent years, its importance has gained attention and become one of the prime concerns of health programmers and managers.3,4 The satisfaction of delivery service helps pregnant women to make a birth plan including delivery site preference, transportation, treatment, and referral in case of complications.5 Maternal satisfaction has been widely recognized as one of the critical indicators of the quality and the efficiency of the health care systems.6 It is a complex and multidimensional measure that is affected by a number of clinical and technical factors, but also by expectations and personal characteristics.7 Long waiting time, unavailability of basic drugs, cleanliness of the environment (delivery room, waiting area, and wards), the cost paid to service, lack of privacy, lack of consideration for cultural practices, and compassionate respectful care are among the major factors that affect maternal satisfaction in developing countries like Ethiopia.8

About 830 women die from pregnancy or delivery related complications around the world every day. Almost all of these deaths occurred in low-resource settings.9 Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for about half of the burden of the world’s maternal and under-five deaths.3 In Ethiopia, the maternal mortality rate is 412 per 100,000 women.10 Only 26% of women gave birth in the health facilities by skilled health providers in Ethiopia and in the Oromia region, 18.8% of women gave birth at health institutions while 81.2% gave birth at home.11 Institutional delivery is the key indicator of maternal mortality prevention which is affected by mothers’ dissatisfaction with delivery services.12

Over the past decades, the government of Ethiopia has expanded health service facilities and increased skilled birth attendants’ coverage; which led to improvements in health service performance and utilization of services at all levels (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Health; Health Sector Development Program IV 2010/11 – 2014/15; unpublished data; 2016). Among them, expansions of health facilities, establish maternal waiting areas, address ambulance services that offer basic transportation services to improve the proximity of maternal services, and instituting measures to ensure all maternal services.13,14 Although government effort is good to improve institutional delivery, the service quality provided by health facilities is still not up to expectations, and the satisfaction of mothers remains a major challenge.4 Even though maternal satisfaction plays a major role in increasing institutional delivery service utilization, the level of maternal satisfaction and associated factors were not well identified. Despite the Ethiopian federal ministry of health implemented compassionate, respectful, and caring as one of the health sector transformation agendas to increase health service utilization, the level of maternal satisfaction to institutional delivery is still low. Therefore, this study assessed the level of maternal satisfaction and factors associated with institutional delivery care among mothers who gave birth in public health facilities in Adea Berga district, West Shewa zone, central Ethiopia with the following specific objectives.

1. What extents of mothers who gave birth in public health facilities were satisfied with services they received from health facilities during labor and delivery care?

2. What are the underlying determinants of maternal satisfaction towards institutional delivery care among mothers who gave birth in public health facilities?

Methods

Study Design, Period, and Area

A community-based cross-sectional study quantitative study supplemented with a qualitative study was conducted among randomly selected 460 women who gave birth in the last 12 months in public health facilities in the Adea Berga district, central Ethiopia from January to March 2020. The reason why qualitative study added was for a deep understanding of factors associated with maternal satisfaction which cannot be addressed by quantitative alone. Adea Berga district is found in West Shewa Zone, Oromia regional, state at a distance of 64 kilometers from Addis-Ababa. The district has 37 kebeles. The total population of the district is 169,560. In the district, institutional delivery was 2253 in the year 2019 according to Adea Berga health office annual report of January 2020. The district has 5 governmental health centers, 1 primary hospital, 35 health posts, and 1 non-governmental health center with a total of 285 health professions including health extension workers.

Source and Study Populations

Source populations were all women 18–49 years of age who gave birth in the last one year in public health facilities before the data collection period in Adea Berga district. Study populations were all women 18–49 years of age who gave birth in public health facilities in the last 12, months in selected sub-districts and included in the study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All mothers who attended delivery services in the last 12 months in public health facilities of Adea Berga district were included in the study. All mothers who were deaf and unable to speak were excluded from the study since they were unable to respond to the questionnaires.

Sample Size Determination

The sample size was determined through the single population proportion formula using the assumptions of 95% confidence interval with a marginal error of 5% and 81.7% prevalence of maternal satisfaction to institutional delivery which was taken from the study conducted in Debre Markos town, Ethiopia15 and design effect 2. By taking the above assumptions, the final sample size was 460 study subjects. For a qualitative study, 36 mothers who gave birth in the last 12 months have participated. Two study participants were selected purposively from each sub-district. The study interviews were held using a semi-structured interview guide with probing questions linked to the maternal satisfaction aspect. The main themes of the conversations are used as sub-headings.

Sampling Technique and Procedure

A multistage sampling technique was used to select the kebeles and households. In the first stage from a total of 37 kebeles in the district, eighteen kebeles were randomly selected. Then the total numbers of women who gave birth at public health facilities in the last 12 months in the selected kebeles were obtained from the community health information system. Then women were proportionally allocated to each selected kebeles according to their size. Finally, a simple random sampling technique was used to select the study participants. For qualitative methods, 36 women who gave birth in the last twelve months at the public health facilities of the district, and live in the selected kebeles but not included in the quantitative study were selected by purposive or judgmental sampling for in-depth interview at household level.

Measurements of Satisfaction with Institutional Delivery Care

The satisfaction measurement questions contain eight questions on health-facility related, two questions on the provision of respect and privacy, and six questions on providers and staff related variables. The questionnaire was adapted from previously conducted similar studies in Ethiopia which in turn was adapted from the Donabedian quality assessment framework.4,16 The reliability of the used questions was checked with Cronbach’s alpha, which was found to be 0.835.

Based on the findings, maternal satisfaction with institutional delivery care was measured where mothers were asked 16 items satisfaction questions. Each questionnaire measures a five-point Likert scale (The 5-point Likert scale response options, scored from 1 to 5, were 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree) which together yield a maximum of 80 and a minimum of 16. Then a response to 16 measuring items added and converted to give an individual level of satisfaction score from 1 to100% for each item. Accordingly, women who scored greater than or equal to 75% of the institutional delivery services questionnaire were considered as satisfied while those who scored less than 75% were considered as dissatisfied which was determined based on the previous studies.17–21

Data Collection Instrument and Procedure

A face to face interviewer-administered was first prepared in English and then translated into Afan Oromo (local language of the area) and translated back to English by language experts to check the consistency. Afan Oromo version questionnaire was used for data collection after the health care provider’s decision to discharge the mothers but before they left health facilities. Eight diploma Nurses who were not working in selected health facilities and four BSc midwifery professionals who were fluent in the local language were recruited for data collection and supervision respectively. Two master’s level public health professionals collected the qualitative data. The contents of the questionnaire include:-socioeconomic and demographic variables, questions related to obstetric, service provider related variables, and health facility-related variables. Interview guides were utilized for in-depth interviews. The interview guide questions that could elicit information regarding health service provider behavior during birth care, health facility-related questions, and overall maternal satisfaction related questions to birth care were used. In-depth interviews were recorded using audio tape recorders.

Data Processing and Analysis

The collected data were cleaned, coded, and entered into EpiData version 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 23 for analysis. The results were presented by texts, percentages, and tables. Both bivariate and multivariate logistic regressions were computed to identify factors associated with maternal satisfaction. Variables with a p-value < 0.25 in bivariate logistic regression were considered as candidates for multivariable logistic regression. Finally, P-value of <0.05 and AOR with 95% CI were used to declare significant association. For the qualitative study, the collected data were translated word by word into English and summarized manually under the main thematic area. The result obtained from the key informant interviews were thematically analyzed and presented in themes.

Ethical Consideration and Consent to Participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review Committee of Ambo University College of medicine and health sciences approved the Ethical clearance of written informed consent. A support letter was obtained from the West Shewa Health office and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants after explaining the objective and aim of the study. The privacy and confidentiality of the study participants were also kept rigorously. Data collectors coded the questionnaire and did not write the name of the study participants during data collection.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

From a total of 460 mothers, 451 responded to the questionnaire by making the response rate of 98%. More than half (51.9%) of the respondents were in the age group of 25–34 with a mean age of 28.53 ±5.3 years. Nearly one-third of the respondents cannot read and write. About 64.7% of women were rural residents [Table 1]).

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Mothers for Maternal Satisfaction and Factors Associated with Institutional Delivery Services in Central Ethiopia 2020 |

Obstetric-Related Characteristics of the Respondents

Two-third, (67.4%) of the study participants had a history of previous institutional delivery. About 79.2% of the respondents delivered by spontaneous vaginal delivery and a majority of 98.7% experienced normal fetal outcomes. Nearly two-thirds of the respondents (65.9%) had a history of ANC follow-up and 60.5% of the skill birth attendants were attended by female health providers [Table 2].

|

Table 2 Obstetric History of Mothers for Maternal Satisfaction and Factors Associated with Institutional Delivery Services in Central Ethiopia 2020 |

Service-Related Characteristics of the Respondents

Regarding respondents’ means of transportation to the health facility, more than half (55%) of the respondents arrived by Ambulance. The majority of women (95.3%) got adequate medical supplies and drugs from health institutions when they gave birth at health facilities. More than half, (52.3%) of the mothers complained about the cleanliness of the delivery rooms [Table 3].

|

Table 3 Service-Related Factors for Maternal Satisfaction and Factors Associated with Institutional Delivery Services in Central Ethiopia 2020 |

Health Providers-Related Characteristics of the Respondents

Among the satisfied study participants, 105 (63.6%) of them got respectful care from their health care providers. About 112 (67.9%) of the satisfied participants reported that health workers introduce themselves before they started to provide any health care. The majority (90.3%) of the satisfied mothers told that as the health care providers asked them informed consent before applying any procedures and examinations in the health facilities [Table 4].

|

Table 4 Health Provider-Related Factors for Maternal Satisfaction and Factors Associated with Institutional Delivery Services in Central Ethiopia 2020 |

The Overall Level of Maternal Satisfaction

In this study, 36.6% of women satisfied and 63.4% of them dissatisfied with institutional delivery services they got from health facilities.

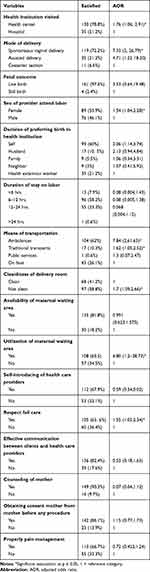

Factors Associated with Maternal Satisfaction Towards Institutional Delivery

Bivariate logistic regression was computed for each independent variable. Variables with p-value < 0.25 were entered into multivariate logistic regression. After controlling for covariates in multivariate logistic regression analysis, mothers who gave birth at health centers had almost two folds higher to be satisfied than the odds of those who gave birth in hospitals (AOR=1.76, CI: 1.06, 2.91). Mothers who gave birth through spontaneous vaginal delivery had 7.33 folds higher odds of satisfaction than those who gave birth through cesarean section (AOR: 7.33, CI: 2, 26.79). Women whose labor was assisted by female health professionals were 1.54 times more likely to be satisfied compared to their counterparts (AOR: 1.54, CI: 1.04, 2.28). Mothers who came to health facilities by ambulance were 7.84 times more likely to be satisfied than those who came to health facilities on foot (AOR: 7.84, CI: 2, 61.63). Women who gave birth in an unclean delivery room of health facilities wore likely dissatisfied than those who gave birth in a clean room (AOR: 1.72, CI: 1.09, 2.66). The odd of maternal satisfaction is 6.8 folds higher among women who utilized maternal waiting areas in health facilities compared to their counterparts (AOR: 6.8, CI: 1.2–38.73). Women who served by respectful health care professionals were 1.55 times more likely to be satisfied than their counterparts (AOR=1.55, CI: 1.03, 2.34) [Table 5].

|

Table 5 Factors Associated with Maternal Satisfaction Towards Institutional Delivery Services 2020 |

Results of the Qualitative Study

About 36 mothers who gave birth in the last 12 months have participated in the in-depth interviews. We stopped the in-depth-interviews on 36 because of reaching idea saturation. The findings from the qualitative study identified three themes and 10 categories that were associated with maternal dissatisfaction with institutional delivery care. The themes included lack of access to health care, respect and dignity in receiving care and maternal waiting rooms at health facilities which are described below.

Lack of Access to Health Care

Most of the participants of the qualitative study stated that they did not receive immediate birth care from health care providers after reaching the health facility. The participants also indicated that there is no adequate Ambulance service for taking mothers to health facilities during labor.

This was supported by a response from an in-depth interview where one participant said: “I delivered my first baby on the road because of transportation problem and lack of ambulance services.” Similarly, the majority of the interviewed mothers had pointed out that the road for ambulance service needs to be improved and the waiting time to get ambulance service should be minimized.

Lack of Respect and Dignity

Besides, they reported that health care providers were un-respectful and unfriendly when providing birth care. This was stated by a 34-year-old woman from Olonkomi sub-district who stated:

The way the receptionist, as well as the midwives, welcome delivering mothers was not good as many women who receive the services were dissatisfied with the care they received.

This is also supported by another 33-year-old woman from Reji-mokoda who stated: “When I arrived at the health center at night, the gatekeepers were too careless to open the door and they were not cooperative to show the appropriate place to get birth care.”

Another participant also indicated that: “some health care providers had an unwelcoming face, which made me angry on the services I received … ”

This was supported by the result obtained from in-depth interviews where a 28 years old woman stated:: ‘’I am very dissatisfied with the way health care providers handled my situation, during my labor. I am in labor and delivery, but they just simply order me to push rather than empathetically helping me during this critical time. Even after I gave birth they were also not checking me and my baby. ”

Lack of Maternal Waiting Room

It was indicated in this study that maternal waiting rooms should be available to minimize the problems of delay to reach the health facility for birth care. This was strongly indicated by one participant of the in-depth interview who stated.

I gave birth in Enchini health center for the second time, I used the maternal waiting rooms for more than 12 hours before I gave birth in recent delivery and I found everything nice; I feel as I am in my home as I get what I want such as coffee, can watch television. I think maternal waiting rooms should be available at all health facilities.

Discussion

The finding of this study showed that maternal satisfaction with the institutional delivery services was 36.6%. It is lower than the studies conducted in Ghana (46.2%) (26,), Arsi Zone, South-East Ethiopia (56%), and other studies (47%).22,23 However, this finding is much lower than the studies conducted in Debre Markos town, Amhara Region (81.7%), Assela Referral Hospital Arsi Zone, Oromia region (80.7%), and Gamo Gofa, South Ethiopia (80%).5,24,25 The possible explanation for the observed difference might be due to the study design differences in which higher satisfaction was observed in the previous studies because they were institutional-based studies, unlike the current study. Moreover, the variation may be due to different infrastructures like road, electrical power, water, ambulance service, and the real difference in the quality of services provided. Another reason for the discrepancy might be due to using a different cuts off points for the level of satisfaction.

Giving birth at health centers was positively associated with maternal satisfaction compared to those who gave at Hospitals. This showed that the mothers are more attracted to the delivery service they got from the health centers, which might be due to the closeness of the health centers to mothers as a household. It may be also since the health center’s staff is more close and familiar to the women, which helps mothers to be treated friendly and without fear. The other probable reasons might be a mother’s perception of a fear hospital environment and additional cost needed for transportation and accommodation to the hospital.

Spontaneous vaginal delivery was an independent predictor of maternal satisfaction in the current study. Contrary to this finding, the studies conducted in West Gojam, Ethiopia and Debre Markos town, Ethiopia20,26 found higher maternal satisfaction to institutional delivery services among women who delivered through cesarean section compared to those who gave birth through spontaneous vaginal delivery. The reason for the differences of these studies might be due to difference in the study settings in which the current study conducted in both urban and rural but, the two previous studies were conducted in urban areas where urban women may know as cesarean section shortens their labor which in turn made them more satisfied.

Mothers whose deliveries were attended by the female health workers were more likely satisfied with the delivery services than those whose deliveries were attended by male health workers. The finding of this study is different from the study conducted in West Arsi Zone, Ethiopia in which maternal satisfaction with delivery services did not differ with the sex of birth attendants. The reason for the discrepancy of the two studies might be due to cultural and religious differences, preferences to account for greater comfort, easy communication, a greater sense of privacy. Means of transportation used to arrive at health facilities were found to be an underlying factor for maternal satisfaction in this study. Mothers who had received ambulance services at arriving at health facilities were more likely satisfied than those who had arrived on foot. This was supported with an in-depth interview result in which 29 years old women stated that… “I do not want to remember what was happening before three years. I delivered my first baby on the road because of transportation problems. Know all things to be nice, thanks to our government, accessibility of road, Ambulance and the like are good. Similarly, majority of the interviewed mothers had pointed out that the road for ambulance service needs to be improved and the waiting time to get ambulance services should be minimized. This might be due to those who obtained ambulance service reach health facility quickly and can get services quickly, but those who do not get ambulances on time may give birth on the road which made them dissatisfied.

The utilization of maternal waiting areas was positively associated with maternal satisfaction. This was supported with the result obtained from the in-depth interview which is mentioned by A 32 years old women as …

I gave birth in Enchini health center for the second times, even if I stayed in the maternal waiting area for more than twelve hours before delivery, everything is very nice I felt as I was in my home and I got what I want, coffee is there, I can watch television and the like are there.

This is because those who stay in the waiting area before labor may get services from healthcare providers that increase confidence towards their health.

Mothers who delivered in the perceived clean delivery rooms were more likely satisfied than their counterparts. The finding is similar to a study conducted in Eretria, in which mothers who perceived that the delivery room and toilet were clean were more likely to be satisfied than their counterparts. The finding is also consistent with a study conducted in Hawassa city, South Ethiopia.27 This also supported with the result obtained from the in-depth interview which is mentioned by A 30 years old women as follows …

I gave birth in Enchini hospital for the second times, though referral linkage even if I go there for other health services, as you can see, everything in there is not clean and not adequate, I slept on unclean bed-sheets, in the unclean room, the toilets were also very dirty.

This might be due to fear of nosocomial infection due to unclean rooms and utensils that in turn made them dissatisfied.

Respectful care of health care providers was an independent predictor of maternal satisfaction in this study. The finding was in line with a study conducted in Addis-Ababa and Mampong-Ashanti district hospital, in Ghana where politeness, courtesy, and respect from health providers were reasons for the higher satisfaction of mothers.28,29 This was supported with the result obtained from the in-depth interview which is mentioned by A 28 years old women Saied that I am very dissatisfied with the way health care workers cooperative with my situation, the way they encouraged me when I was on labor and delivery they just simply order me to push rather than empathetically helping me during this critical time. Even after I gave birth they were also not checking me and my baby. They said to me and my family tomorrow you will go home without telling anything we need to do at our home.

Another respondent said; -

Most of the health care workers were disrespectful they behaved by which the delivery mother is not expected from them, most of the time, they were irritable and shouting; overall, they did not treat me in a friendly way.

If the health care providers give whatever qualified services to mothers without respecting mothers and being polite to them, they could never satisfy them. As far as we know, our study is the first to find a significant association of maternal satisfaction with respectful care of health care providers, maternal waiting areas, and means of transportation in Ethiopia.

Limitations of the Study

Since the time between birth assistance and data collection is a very long period and some important aspects of childbirth can be overlooked or minimized and recall bias might occur.

Conclusion

The overall level of maternal satisfaction towards institutional delivery was low in this study due to lack of adequate ambulance service for taking mothers to health facilities during labor, un-respectful, unwelcoming face, and unfriendly approach of health care providers when providing birth care. Spontaneous vaginal delivery, being attended by female sex health workers, ambulance services, cleaned delivery rooms, and respectful care were factors associated with maternal satisfaction. Health managers in the study area have to look at their delivery service seriously and modify it to meet the expectation of the mothers.

Abbreviations

ANC, Antenatal Care; CRC, Compassionate Respect full Care; FMOH, Federal Ministry of Health; SPSS, Statistical Package for Social Sciences; SVD, Spontaneous vaginal delivery.

Data Sharing Statement

The data sets which support this article can be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Review Committee of Ambo University College of medicine and health sciences approved the Ethical clearance of written informed consent. A support letter was obtained from the West Shewa Health office and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants after explaining the objective and aim of the study. The privacy and confidentiality of the study participants were also kept rigorously. Data collectors coded the questionnaire and did not write the name of the study participants during data collection.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Ambo University for allocating funds to conduct the study. We would also like to express our deepest appreciation to all individuals who supported us during this research work for their indispensable contributions. Last but absolutely not least, the contribution of the study participants is greatly appreciated.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to conception, design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit it to the current journal. They gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

Funding for the research was provided by Ambo university research, consultancy, and community service director office. Besides, financial support, the funding body had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest for this work or regarding this work and publication of this manuscript.

References

1. WHO Global Strategy on People-Centered and Integrated Health Services: Interim Report. World Health Organization; 2015.

2. Safer MP. Making Pregnancy safer: The Critical Role of the Skilled Attendant. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

3. Kea AZ, Tulloch O, Datiko DG, Theobald S, Kok MC. Exploring barriers to the use of formal maternal health services and priority areas for action in Sidama zone, southern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):96. doi:10.1186/s12884-018-1721-5

4. Mullan Z. Transforming health care in Ethiopia. Lancet Global Health. 2016;4(1):e1. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00300-9

5. Bennett AM. A model for direct entry midwifery education and deployment in Ethiopia: transforming rural communities and health care to save lives 2014 [thesis]. UTS; 2014. Available from: https://opus.lib.uts.edu.au/handle/10453/35958.

6. Naghizadeh S, Sehhati F, Barjange S, Ebrahimi H. Comparing mothers’ satisfaction from ethical dimension of care provided in labor, delivery, and postpartum phases in Tabriz’s educational and non-educational hospitals in 2009. J Res Health. 2011;1(1):82.

7. Tocchioni V, Seghieri C, De Santis G, Nuti S. Socio-demographic determinants of women’s satisfaction with prenatal and delivery care services in Italy. Int J Quality Health Care. 2018;30(8):594–601. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzy078

8. Geerts CC, van Dillen J, Klomp T, Lagro-Janssen AL, de Jonge A. Satisfaction with caregivers during labour among low risk women in the Netherlands: the association with planned place of birth and transfer of care during labour. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):229. doi:10.1186/s12884-017-1410-9

9. Atiya KM. Maternal satisfaction regarding quality of nursing care during labor and delivery in Sulaimani teaching hospital. Int J Nursing Midwifery. 2016;8(3):18–27.

10. Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):462–474. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00838-7

11. Wilunda C, Putoto G, Dalla Riva D, et al. Assessing coverage, equity and quality gaps in maternal and neonatal care in sub-saharan Africa: an integrated approach. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0127827. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127827

12. Tessema GA, Laurence CO, Melaku YA, et al. Trends and causes of maternal mortality in Ethiopia during 1990–2013: findings from the Global Burden of Diseases study 2013. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):160. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4071-8

13. Fekadu GA, Ambaw F, Kidanie SA. Facility delivery and postnatal care services use among mothers who attended four or more antenatal care visits in Ethiopia: further analysis of the 2016 demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):64. doi:10.1186/s12884-019-2216-8

14. Maternal Mortality Fact Sheet. World Health Organization; Fact Sheet. 2014.

15. Koblinsky M, Tain F, Gaym A, Karim A, Carnell M, Tesfaye S. Responding to the maternal health care challenge: the Ethiopian Health Extension Program. Ethiopian J Health Development. 2010;24:1. doi:10.4314/ejhd.v24i1.62951

16. Tarekegn SM, Lieberman LS, Giedraitis V. Determinants of maternal health service utilization in Ethiopia: analysis of the 2011 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):161. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-14-161

17. Turkson P. Perceived quality of healthcare delivery in a rural district of Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2009;43:2. doi:10.4314/gmj.v43i2.55315

18. Amdemichael R, Tafa M, Fekadu H. Maternal satisfaction with the delivery services in Assela Hospital, Arsi zone, Oromia region. Gynecol Obstet. 2014;4(257):2161.

19. Bitew K, Ayichiluhm M, Yimam K. Maternal satisfaction on delivery service and its associated factors among mothers who gave birth in public health facilities of Debre Markos Town, Northwest Ethiopia. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:2015. doi:10.1155/2015/460767

20. Getenet AB, Teji Roba K, Seyoum Endale B, Mersha Mamo A, Darghawth R. Women’s satisfaction with intrapartum care and its predictors at Harar hospitals, Eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Nursing: Research and Reviews. 2019;9:1-11.

21. Abera M, Belachew T, Belachew T. Predictors of safe delivery service utilization in Arsi Zone, South-East Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2011;21:3.

22. Shankar KN, Bhatia BK, Schuur JD. Toward patient-centered care: a systematic review of older adults’ views of quality emergency care. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(5):529–50. e1. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.07.509

23. Tesfaye R, Worku A, Godana W, Lindtjorn B. Client satisfaction with delivery care service and associated factors in the public health facilities of Gamo Gofa Zone, southwest Ethiopia: in a resource limited setting. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2016;2016:2016. doi:10.1155/2016/5798068

24. Amdemichael RTM, Fekadu H. Maternal satisfaction with the delivery services in Assela Hospital, Arsi Zone, Oromia Region. Gynecol Obstet. 2014;4:257.

25. Asres GD. Satisfaction and associated factors among mothers delivered at Asrade Zewude Memorial Primary Hospital, Bure, West Gojjam, Amharic, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. Global J Med Res. 2018.

26. Edaso A, Teshome G. Mothers’ satisfaction with delivery services and associated factors at health institutions in west Arsi, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. MOJ Womens Health. 2019;8(1):110-119.

27. Tesfaye HT. Statistical Analysis of Patients’ Satisfaction with Hospital Services: a Case Study of Shashemene and Hawassa University Referral Hospitals, Ethiopia. 2012. Available from: https://www.statistics.gov.hk/wsc/CPS202-P31-S.pdf.

28. Sawyer A, Ayers S, Abbott J, Gyte G, Rabe H, Duley L. Measures of satisfaction with care during labour and birth: a comparative review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):108. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-13-108

29. Srivastava A, Avan BI, Rajbangshi P, Bhattacharyya S. Determinants of women’s satisfaction with maternal health care: a review of literature from developing countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):97. doi:10.1186/s12884-015-0525-0

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.