Back to Archived Journals » Robotic Surgery: Research and Reviews » Volume 3

Management of pelvic organ prolapse in the elderly – is there a role for robotic-assisted sacrocolpopexy?

Authors Narins H, Danforth TL

Received 2 March 2016

Accepted for publication 22 May 2016

Published 17 October 2016 Volume 2016:3 Pages 65—73

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/RSRR.S81584

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Masoud Azodi

Hadley Narins, Teresa L Danforth

Department of Urology, The State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA

Abstract: Abdominal sacrocolpopexy is considered the gold standard treatment for symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Since its introduction, robotic-assisted sacrocolpopexy has emerged as a popular minimally invasive alternative to open repair. Epidemiologic data suggest that the number of women seeking surgical treatment for POP will increase to ~50% by 2050, and many of these women will be elderly. Advanced age should not preclude elective POP surgery. Substantial data suggest that medical comorbidities and other preoperative markers may be more important than age in predicting adverse surgical outcomes. POP surgery in the elderly has been extensively studied and found to be safe, but there is a paucity of information regarding robotic-assisted sacrocolpopexy in this population. Data are only beginning to emerge regarding the safety and efficacy of robotic surgery in the elderly, with most studies focusing on oncologic procedures. Preliminary studies in this setting suggest that elderly patients may benefit from a minimally invasive approach, although given their limited physiologic reserves, appropriate patient selection is essential. The purpose of this review article is to evaluate the stepwise management of POP in the elderly female, with a focus on the safety and feasibility of a robotic approach.

Keywords: pelvic organ prolapse, robotic surgical procedures, abdominal sacrocolpopexy, aged

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a highly prevalent disorder affecting as many as 50% of parous women,1 with women above 60 years representing the vast majority presenting for management of this condition.2 Given the aging of the “baby boomer” population, estimates have predicted a substantial increase in those seeking treatment in the future, with a shift toward a more elderly demographic.3 Although POP is not a life-threatening condition, morbidity can be profound and appears to increase with age.4

In the past, conservative management with observation or a pessary represented the mainstay of treatment in the elderly, with obliterative surgery utilized in some cases. However, a number of more invasive approaches may be applied in this population. Vaginal surgery has been well studied and may be safely utilized.5–7 Given the traditional teaching that vaginal surgery is quicker and safer,8 this approach has typically been favored over abdominal surgery in the elderly.9 Very little data exist to compare vaginal versus intra-abdominal surgical approaches in the elderly, although some suggest that an abdominal approach may be no more risky than a vaginal approach. There is even less data regarding robotic surgery for elderly women with POP. With the advent and rapid expansion of robotic surgery, robotic-assisted sacrocolpopexy (RASC) is only beginning to be applied in the geriatric population.

The purpose of this review article is to evaluate the stepwise management of POP in the elderly female, with a focus on the safety and feasibility of a robotic approach.

Methods

This is a literature review. We searched the following databases for published studies in English language: PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and MedlinePlus. Keywords used included pelvic organ prolapse, vaginal vault prolapse, urogenital prolapse, robotic sacrocolpopexy, laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy, abdominal sacrocolpopexy, and surgery in elderly. Searches were conducted by manuscript authors. Full-text articles were reviewed by the authors for inclusion.

Anatomy

Conceptually, one may divide the female pelvis into three compartments: anterior, apical, and posterior. The anterior compartment includes the bladder, bladder neck, and urethra. The apical compartment includes the uterus (or cul-de-sac after hysterectomy). The posterior compartment includes the rectum, anal canal, and perineum. Bridging these structures is the pelvic support, consisting of bones, ligaments, fascia, and muscle.10 POP is classified according to the affected compartment. A cystocele is prolapse of the anterior compartment, in which the bladder descends toward the vaginal introitus. A rectocele is prolapse of the rectum, which compresses the posterior vaginal wall. Vaginal vault prolapse or an enterocele involves descent of the uterus and/or bowel. Loss of apical support where the paracolpium suspends the uterus leads to POP with or without loss of support of the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis at the lateral vagina.11

Several systems exist to grade POP. The Pelvic Organ Prolapse-Quantification (POP-Q) system was created to provide an objective measure of POP, and has emerged as the most commonly utilized method. Grades are assigned according to the amount of prolapse during Valsalva.

- Stage 0: no prolapse

- Stage I: distal prolapse >1 cm proximal to the hymen

- Stage II: distal prolapse within 1 cm of the hymen, either proximal or distal

- Stage III: distal prolapse >1 cm below the hymen without complete eversion

- Stage IV: complete vaginal eversion.

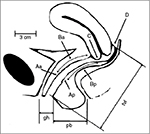

To further characterize the prolapse by compartment, nine points of measure are defined in relation to the hymenal ring (Figure 1).12 The hymenal ring is defined as zero. Prolapse above the hymenal ring is designated as a negative number, whereas prolapse beyond the hymenal ring is given a positive designation.13 The POP-Q system allows physicians to have a consistent way to report and measure the degree of POP, both clinically and for research purposes.

| Figure 1 POP-quantification. Notes: Six sites (points Aa, Ba, C, D, Bp, Ap) as well as the gh, tvl, and pb are all used for the quantification of POP. Reprinted from Am J Obstet Gynecol, 175, Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, et al, The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction, 10–17, copyright 1996, with permission from Elsevier.12 Abbreviations: gh, genital hiatus; pb, perineal body; POP, pelvic organ prolapse; tvl, total vaginal length. |

Evaluation

Evaluation of POP in the elderly follows the same model as in the general population. A detailed history and physical exam should be performed. The history should focus on specific questions to address common prolapse complaints. These include sensation of vaginal bulge, pelvic pressure, low back pain associated with POP, uterine ulceration/bleeding/infection, and splinting or digitation required for voiding or defecation. Any irritative or obstructive urinary symptoms should be addressed, as should bowel complaints. The practitioner should inquire as to the patient’s sexual activity status, as colpocleisis is not an appropriate surgical option for those desiring to maintain sexual function. In addition, the presence or absence of preoperative dyspareunia should be documented. History of abnormal uterine bleeding, gynecologic malignancy, or abnormal pap smears should be elucidated. Medical comorbidities and functional status may direct the surgeon toward conservative versus operative management. If the patient wishes to pursue surgical intervention, her functional status plays a key role in determining which option is most appropriate for her. Surgical history is essential to guide future operative approaches (eg, extensive abdominal surgeries might steer one away from a robotic approach). If the patient has not undergone previous hysterectomy, the decision must be made whether to preserve the uterus or to perform a hysterectomy at the time of surgery.9

Although prolapse beyond the hymen generally predisposes to more severe symptoms, there is a lack of strong evidence correlating prolapse stage with the degree of symptomatology. In general, lower stages of prolapse are associated with stress urinary incontinence (SUI), whereas SUI tends to decrease in the higher stages secondary to obstruction at the bladder neck caused by prolapse of the anterior vaginal compartment. The only symptom that is consistent in patients with high-grade prolapse is the presence of a vaginal bulge.14 In the CARE trial, preoperative symptom scores were found to be more severe in women with stage II than stage III POP and women with stage IV prolapse had symptoms similar to those with stage III, indicating there was little correlation between objective prolapse grading and symptom severity.15 Notably, women with a history of prior pelvic surgery showed no difference in bother regardless of their prolapse stage. Careful history taking to assess the degree of bother is, therefore, a more useful clinical indicator than the degree of prolapse. The decision to proceed with treatment should be determined by the patient’s symptoms rather than the POP-Q score. It is especially important to recognize that patients with asymptomatic prolapse often do not need treatment.

The physical exam should include an overall exam focusing on the abdominal and pelvic exam with assessment of prolapse in the lithotomy and standing positions. The anterior, posterior, and apical compartments should be evaluated for POP and graded using the POP-Q staging criteria. The examiner should rule out occult SUI by cough-leak test in the lithotomy and standing positions with reduction of the prolapse.16 Rectal exam assesses for tone as well as presence of rectocele. If voiding dysfunction is elicited in the patient’s history, urodynamics may be performed at the examiner’s discretion.17 Attention to the patient’s previous abdominal incisions will help with surgical planning. It is also important to assess elderly patients’ mobility, especially in their hips, as decreased mobility could make positioning in the operating room challenging.

Once assessment is completed and bother is assessed, all options for treatment should be discussed with the patient before a decision is made. Options for symptomatic POP include conservative management versus operative intervention. If the patient is bothered by symptoms or having potentially harmful sequelae, expectant management is not appropriate. Complications such as uterine bleeding or infection, hydronephrosis, or urinary retention mandate intervention. Women with advanced prolapse who elect conservative management should be routinely examined to ensure such disorders have not developed.14

Nonoperative management

The least invasive option is observation with or without pelvic floor physiotherapy. Multiple studies have shown benefit from pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT).18 Cochrane analysis from 2011 suggests that PFMT improves symptoms, compared to no intervention.19 Similarly, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated both subjective relief of prolapse symptoms and objective improvement of prolapse scores.20 PFMT may be unavailable in certain regions, and requires a fair amount of patient commitment and effort. Results are not as dramatic as other interventions; however, there is little, if any, associated risk, and this may be a good initial option for those with lower grades of prolapse.9

Pessaries have been extensively used in the elderly population. They support pelvic organs and may be utilized to manage SUI in addition to prolapse. Advantages include avoidance of surgery, improvement in clinical outcomes such as vaginal bulge and quality of life scores, and in some patients, improvement in voiding and bowel symptoms. On the other hand, there are well-known complications associated with pessary use. If not properly maintained with periodic removal and cleaning, infection and tissue erosion may occur. In severe cases of pessary neglect, fistulas have been reported. With hollow-shaped ring pessaries, herniation of the vaginal wall may lead to tissue incarceration.21 Nevertheless, pessaries are typically well tolerated and successful in those desiring nonoperative intervention. In a prospective study, Lone et al found improvement in vaginal, bowel, urinary, and quality of life scores in women with POP treated with surgery or pessary; there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups at 1 year.22 Similarly, Abdool et al evaluated women 1 year after surgery or pessary use, and found the only significant difference to be increased frequency of intercourse in the surgery group. This was not significant when controlled for age.23 Pessaries may be an excellent option for symptomatic women who wish to avoid surgery or are poor surgical candidates, so long as appropriate pessary care is assured. As pessary is unsuccessful, not tolerated, or not desired, various forms of surgical intervention are available.

Surgical management of POP in the elderly

Preoperative evaluation

Functional status, typically defined as the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status class, is a commonly used measure of preoperative risk. In a retrospective review of women >60 years undergoing POP repair, Greer et al found that ASA status was significantly associated with increased length of stay (LOS) and postoperative complications, even when adjusting for age and other variables.24 In a prospective study that included 45% vaginal, 33% robotic, 14% open, and 4% obliterative repairs, Greer et al again found that ASA status is an independent predictor of LOS. Recent weight loss and anemia were important preoperative markers that predicted failure to return to baseline functional status. In their experience, most women returned to baseline functional status as early as 12 weeks after surgery.25

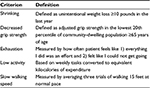

In addition to commonly used measures such as ASA status, the concept of frailty has emerged as a marker for increased surgical risk. Frailty is generally defined as low physiologic reserve and limited ability to withstand stressors. Measures to evaluate frailty include weight loss, weakness as measured by grip strength, exhaustion, low activity, and slow walking speed (Table 1).26 Makary et al retrospectively evaluated frailty in 594 patients over 65 years undergoing various types of surgery. They found that preoperative frailty increases the risk of postoperative complications, LOS, and probability of discharge to an institutional setting. In their analysis, frailty added predictive power to more commonly used preoperative measures such as ASA status. In the authors’ experience, evaluation of frailty was easy to administer, taking less than 10 minutes in the office.

| Table 1 Frailty criteria |

It is not clear whether a more thorough preoperative evaluation in the geriatric population may improve outcomes. Richter et al compared a standard versus enhanced preoperative assessment of elderly women undergoing elective pelvic floor surgery. They did not find a benefit in the enhanced evaluation group. They acknowledge that they may have failed to detect a difference due to the overall good health and functional status in their cohort.27 Nevertheless, it is important to rule out subtle cognitive defects in the elderly, as the risk of perioperative mortality increases by a factor of two to three times in patients with dementia.28

Many studies have evaluated the safety of gynecologic surgery in women >75–80 years, and the data suggest that in appropriate patients, it is safe and feasible.6,7,29–31 However, given the heterogeneity of data design and reporting, it is unclear which surgical approach offers the best balance of efficacy and safety, and how best to stratify these patients.

Obliterative surgery

Historically, obliterative surgery has been considered the least risky surgical option for elderly women with prolapse. Colpocleisis involves total or partial vaginal closure with reduction of POP. Advantages include shorter operating time, ability to perform the surgery under spinal or even local anesthesia, good durability, and relative ease of surgery.32 There is significant heterogeneity in outcome reporting in colpocleisis literature.

The definition of surgical success varies widely between studies, and in some cases, it is poorly defined. Nevertheless, colpocleisis appears to be a very efficacious surgery, with reported success rates across studies ranging from 91% to 100%. In elderly women with high-grade prolapse, outcomes for obliterative surgery may be comparable to those for reconstructive surgery. Murphy et al retrospectively reviewed their cohort of women aged 65 years and older with stage III and IV POP who had undergone vaginal reconstructive surgery (VS) and colpocleisis.33 They had equal success between the two groups (defined as no prolapse recurrence beyond the hymen or need for further surgery). There was no significant difference in their satisfaction scores postoperatively. In their prospective cohort study with a similar patient population, Barber et al found no significant difference in the objective or subjective outcomes between the obliterative and reconstructive approaches.34 Women in both groups showed benefit in the domains of bodily pain, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional scales, and mental health summary score. Surgical time was shorter in the obliterative group.

While colpocleisis is considered to be a fairly low-risk surgery, there is little data specifically addressing how the very elderly fare. Serious perioperative complications of a cardiopulmonary or vascular nature occur in approximately 2%. Minor surgical complications such as urinary tract infection (UTI) and fever appear to be in the range of ~15%.35 Krissi et al retrospectively examined colpocleisis outcomes in their cohort, specifically comparing those patients of age <80 and >80 years.32 There was no significant difference in the subjective or objective cure rate, or in intraoperative complications between groups. Postoperative complications were minor and not related to age. Although their study was limited by its retrospective design and small cohort, they demonstrated that octogenarians and even nonagenarians may have successful outcomes and low complication rates similar to those of “younger elderly” women.

Although smaller series fail to show any difference in complication rates, there is some evidence that colpocleisis carries a lower risk of morbidity than reconstructive surgery. In their review of 264,340 women undergoing prolapse repair, Sung et al found that women above 80 years had a 17% risk of complication for obliterative procedures versus a 24.7% risk for reconstructive procedures.36 They also had a lower risk of mortality, although this did not reach statistical significance.

Colpocleisis is an excellent choice for women with symptomatic prolapse who do not wish to use pessaries and preserve penetrative sexual function. It is very effective in both objective and subjective measures, and carries low risk of complications.

Transvaginal repair

When a reconstructive approach is desired, vaginal surgery has generally been favored in the elderly. Restoration of apical support by the vaginal approach may be achieved by uterosacral ligament fixation, sacrospinous ligament fixation (SSLF), and iliococcygeus suspensions, with anterior and/or posterior repair. Although success rates are not as high as abdominal sacrocolpopexy (ASC), it is believed that lower complication risks in vaginal surgery offset the lower efficacy.37 In the OPTIMAL trial, there was no difference between uterosacral ligament fixation and SSLF, which are the two most commonly used approaches.38 The surgeon may utilize mesh or native tissue for repair. In a Cochrane review, use of mesh for transvaginal reconstructive surgery has been shown to decrease reoperation for anterior wall prolapse, patient awareness of prolapse postoperatively, and the finding of prolapse on follow-up examination.39 However, transvaginal mesh is associated with mesh erosion in 11%–18% of patients undergoing surgery for POP, leading to higher reoperation rates in the mesh group, most often for revision and/or removal of mesh. The authors conclude that there is not a clear role for mesh in primary transvaginal POP surgery.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the safety of vaginal repair in the elderly. Moore et al reviewed a cohort of women undergoing vaginal POP repair and anti-incontinence procedures. They divided their patients into those aged ≤55, 56–69, and ≥70 years, and found no statistical difference in perioperative complications among the three groups.5 In a prospective study of vaginal prolapse repair in women over 75 years, Mohammed et al demonstrated no systemic complications related to anesthesia or surgery, and showed improvement in quality of life parameters.6 Gabriel et al utilized the Prolift™ (Ethicon Women’s Health & Urology, Somerville, New Jersey, USA) technique in 62 women above 80 years; they incurred only one intraoperative complication, with no major postoperative complications, and two patients requiring reoperation. Subjective data were not reported.7

Although the overall complication rate is low in transvaginal repair, severe complications and death are known to occur. In a review of SSLF in a cohort of 25 women over age 80 years, Nieminen and Heinonen reported several adverse outcomes: four patients (16%) suffered cardiovascular complications, including one patient who suffered a myocardial infarction following hemorrhage and another who died of a pulmonary embolism.40 All of these serious complications occurred in women with known vascular disease. Similarly, in a cohort of women aged 70–85 years who underwent major elective gynecologic surgery, Toglia et al reported 10% incidence of cardiac complications, and 11% of their patients required intensive care unit care.41 Stepp et al retrospectively evaluated 283 patients who had undergone elective urogynecologic surgery.42 In their group, the vast majority underwent vaginal surgery, with a minority undergoing abdominal or laparoscopic approach. Their incidence of one or more significant perioperative complications was 25.8%. Of interest, in their cohort, ASA status was not an independent predictor of complication.

In a large cohort, Sung et al found that for each decade of life over age 50 years, the risk of complication and death following urogynecologic surgery increases.36 The risk of mortality in women ≥80 years was 13.6 times greater than that in the youngest cohort of women <60 years, even after adjusting for comorbidities. Overall, the mortality rate in their cohort was 0.04%. These results are echoed in a smaller study of 508 patients undergoing urogynecologic surgery, the majority by vaginal approach.43 Women over 65 years had almost twice the risk of clinically significant postoperative complications (12.5% vs 6.7%).

Given the inherent risk of surgery in general, the vaginal approach seems to provide good results with an acceptable safety profile. Elderly patients should be counseled that in spite of the low-risk nature of these procedures, their age still might place them at an increased risk for morbidity and mortality.

Abdominal sacrocolpopexy

ASC is considered the “gold standard” for prolapse repair, with superior durability for apical repair than the transvaginal reconstructive approaches.1 When defining success as absence of apical prolapse, studies report a range of 78%–100%. When defined as no postoperative prolapse in any compartment, this success rate decreases somewhat to 58%–100%.44 ASC is indicated in cases of failed prior vaginal repair, isolated apical prolapse, and in individuals who wish to remain sexually active, as it maximizes functional vaginal length.

These benefits must be weighed against the longer operating time, longer recovery time, and increased cost of the abdominal approach.1 In their review of ASC, Nygaard et al summarize the most common complications.44 UTI is reported at 10.9% overall. Hemorrhage or transfusion occurs in 4.4%. Intraoperative complications include cystotomy in 3.1%, enterotomy in 1.6%, and ureteral injury in 1%. Postoperatively, 1.1% requires reoperation for small bowel obstruction.

Robotic-assisted sacrocolpopexy

Patient selection

Given the significant morbidity and recovery time of open repair, minimally invasive surgery is an attractive alternative to the traditional open approach. Since the da Vinci® robot (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) has been approved, it has gained widespread use in pelvic surgery and RASC is commonly performed in lieu of ASC.16 The decision to proceed robotically as opposed to open or laparoscopically depends on a number of factors, including access to the robot, surgeon preference and comfort, patient preference, and the ability of the patient to tolerate a minimally invasive surgery. While there is some variation among surgeons, the principles of RASC are the same as ASC.44

The fundamental steps are as follows. After general anesthesia is induced, the patient is placed in the dorsal lithotomy position. Appropriate padding of pressure points is essential, as is securing the patient to the table to prevent sliding and avoiding pressure ulcers or neuropathy. After pneumoperitoneum is established and ports are placed, the patient is placed in steep Trendelenburg position to allow the abdominal viscera to fall caudally, out of the surgical field, and the robot is docked between her legs. The peritoneum is incised at the vaginal apex and a plane is developed in the vesicovaginal space down to the level of the bladder neck. A posterior plane is developed in the rectovesical space as distally as possible toward the anal sphincter in a similar fashion. The posterior space is not always developed if the patient has isolated apical and/or anterior vaginal wall prolapse, as support with an anterior approach is usually adequate. The bowel is retracted to the left upper quadrant, and an incision is made in the posterior peritoneum over the sacral promontory. The surgeon must be mindful of the left common iliac vein and right ureter, which are susceptible to injury during this maneuver. The anterior longitudinal ligament is identified and cleared, with care taken to avoid injury of sacral vessels, as bleeding can be challenging to control and may lead to significant hemorrhage. A tunnel is then made under the peritoneum for retroperitonealization of the mesh at the end of the procedure. A single-arm or Y-shaped polypropylene mesh is introduced into the peritoneum and the short arms of the mesh are sutured to the anterior and posterior vaginal wall. The long arm is tunneled under the peritoneum attached to the sacral promontory using nonabsorbable suture. The mesh is then retroperitonealized to avoid exposure of mesh to bowel.11,45 Concomitant procedures including hysterectomy, vaginal anterior and posterior repairs, and incontinence procedures are frequently performed. Discussion of these concomitant procedures is beyond the scope of this review.

Outcomes

RASC literature is less mature than that of ASC, but success rates appear to be similar, ranging from 79% to 100% by objective measures and from 88% to 79% by subjective measures.11 In the short term, RASC appears to incur less blood loss and allow for a shorter LOS.46 In their meta-analysis, Serati et al concluded that RASC decreases blood loss and hospital stay, although operative times are longer.47 Longer-term outcomes also seem to be comparable between the open and robotic groups. In their retrospective cohort, Geller et al compared 23 patients following RASC to 28 patients who had undergone ASC. They found no difference between improvement in POP-Q score, pelvic score function, and sexual function at 44 months postoperatively.48 Similarly, Linder et al reported freedom from repeat surgery to be 90% at 6 years, with 80% of subjects indicating they would recommend RASC to a family member or friend.49

Two meta-analyses are available comparing robotic versus laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy.50,51 In a meta-analysis of 264 RASC versus 267 laparoscopic procedures, the estimated blood loss (EBL), objective and subjective success rates were similar.50 The only significant differences between the two approaches were longer operative times and higher cost with RASC. In a meta-analysis of nine papers including 1,157 patients, there was no significant difference in anatomical outcomes, hospital stay, or postoperative quality of life.51 In the meta-analysis by Pan et al, the robotic approach did confer longer operative times50; however, DeGouveia et al did find increased postoperative pain in the RASC group.51

Complications

Complications may occur intraoperatively or postoperatively in the long or short term. Intraoperative complications common to open and robotic approaches include hemorrhage, vaginotomy, cystotomy, ureteral injury, and enterotomy. Additional risks unique to the robotic approach include need for open conversion, trocar site bleeding, air embolus, trocar injury, and complications related to the unique anesthetic demands of minimally invasive surgery.45 In the short term, some well-known complications of RASC and ASC include UTI, urinary retention, fever, ileus, and cardiopulmonary complications. In the long term, perhaps the most dreaded complication relates to mesh, with erosion and extrusion rates reported in the 0%–10% range.11 In their cohort, Geller et al found no difference in mesh complications between the ASC and RASC groups.48 Compared to the laparoscopic approach, the overall mortality was noted to be the same with fewer overall complications seen in the robotic approach, but only when the procedure was combined with a hysterectomy.51 Pan et al confirmed similar complication rates between RASC and the laparoscopic approach.50

Other complications include symptomatic failure requiring further operative intervention, incisional hernias, new-onset dyspareunia, and new or worsening urinary or bowel complaints, among others. In a larger cohort, Geller et al found lower EBL and higher incidence of postoperative fever in the RASC group. No difference was found in any other postoperative complications.46 This limited data suggest similar complication rates between the open and robotic approaches, but more studies are needed.

Robotic surgery in the elderly

Although age plays a role in the decision-making process, operative intervention should not be withheld on the basis of age alone. In the preoperative evaluation for any noncardiac surgery, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association consider age to be only a minor cardiac risk factor.28 Nevertheless, robotic surgery introduces physiological stressors that may not be tolerated by the elderly. From an anesthesia perspective, multiple challenges exist. Patient positioning renders their access to the airway quite challenging should airway difficulties arise. The steep downward Trendelenburg position introduces many physiologic concerns. Upper airway and brain edema has been reported. Lung compliance decreases by more than 50%, as do mean pulmonary artery and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure. Subcutaneous emphysema is known to occur, which may significantly contribute to CO2 absorption. In patients with underlying lung disease, CO2 insufflation may cause pulmonary complications in the postoperative period. The combination of pneumoperitoneum and Trendelenburg increases left ventricular filling pressures, and cardiac output may decrease. Systemic vascular resistance and mean arterial pressure increase. Renal, splanchnic, and portal perfusion decrease. The renin–angiotensin system is activated with subsequent increase in vasopressin levels.51

Known physiologic difficulties of robotic surgery must be weighed against potential benefits. Minimally invasive surgery is associated with decreased postoperative pain, shorter LOS, and a more rapid return to baseline than open surgery.52 Other studies have shown quicker return of bowel function, lower incidence of postoperative pneumonia and cardiac complications, and decreased blood loss.53,54

Robotic surgery has been utilized frequently in recent years for elderly patients in the urologic oncologic population. The oncologic cohort of patients differs from urogynecologic patients in that oncologic patients are at higher risk for embolic events and may have more comorbidities. In their case, surgery is not elective. However, the perioperative and postoperative risks are largely outweighed by the potential survival benefit of extirpative surgery. In spite of these differences, the experience in these oncologic geriatric patients offers insight on the feasibility of robotic pelvic surgery in the elderly.

Although robot-assisted radical prostatectomy is typically offered to younger patients, Rogers et al evaluated their experience in men ≥70 years with high-risk disease who elected surgery over medical management. Similar to younger men, their median duration of stay was 1 day, with no patients admitted longer than 3 days. It is likely, given the bias against robot-assisted radical prostatectomy in older men, that this represented a very healthy group.55 In contrast, patients with advanced bladder cancer tend to have multiple comorbidities. Two studies retrospectively compare outcomes of patients undergoing robot-assisted radical cystectomy versus open cystectomy. In both studies, EBL and LOS were lower in the robotic group. One found no difference in complications, whereas the other had a decreased complication rate in the RARC group.56,57 These studies demonstrate the feasibility of robotic pelvic surgery in the elderly population.

We are only aware of one study that specifically compares the outcomes of elderly women who undergo RASC versus another reconstructive approach. Robinson et al retrospectively evaluated women >65 years who underwent RASC and VS. Their primary objective was to compare perioperative complications between the two groups. Overall, the RASC group suffered fewer postoperative complications. However, these results may have been skewed by patient selection; the VS group was slightly younger than the RASC group (70 vs 74 years), with more comorbidities. Still, it provides good preliminary evidence that elderly women may safely undergo RASC without higher risk than VS.58

Limitations of this study include that is it a literature review. Data from the literature specific to the elderly population are sparse, thereby making it difficult to do a meta-analysis. Further prospective studies specifically looking at the feasibility of robotic surgery for POP in the elderly based on frailty, as well as the outcomes need to be done to assess the true safety and efficacy of these procedures.

Conclusion

POP is an increasingly prevalent condition, and with the aging of the US population, surgical demand among the elderly will increase substantially in the upcoming decades. Conservative treatment, obliterative surgery, and transvaginal repair have been shown to be acceptably safe and efficacious in the elderly. Very little is currently known about the relative safety and efficacy of RASC in older women. In the urologic oncology world, small series have demonstrated comparable outcomes between open and robotic surgery in geriatric patients. It is possible that the same may be said in elective POP, but further research is needed. Preoperative assessment tools such as functional status and frailty measurements may aid decision making, but these tools have not been validated in this setting.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Schmid C. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; 4:CD004014. | ||

Luber KM, Boero S, Choe JY. The demographics of pelvic floor disorders: current observations and future projections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(7):1496–1501; discussion 1501–1493. | ||

Wu JM, Kawasaki A, Hundley AF, Dieter AA, Myers ER, Sung VW. Predicting the number of women who will undergo incontinence and prolapse surgery, 2010 to 2050. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(3):230.e231–e235. | ||

Svihrova V, Svihra J, Luptak J, Swift S, Digesu GA. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in general population with pelvic organ prolapse: a study based on the prolapse quality-of-life questionnaire (P-QOL). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;182:22–26. | ||

Moore T, Tubman I, Levy G, Brooke G. Age as a risk factor for perioperative complications in women undergoing pelvic reconstructive surgery. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2010;16(5):290–295. | ||

Mohammed N, Raschid Hoda M, Fornara P. Prolapse surgery in octogenarians: are we pushing the limits too far? World J Urol. 2013;31(3):623–628. | ||

Gabriel B, Rubod C, Córdova LG, Lucot JP, Cosson M. Prolapse surgery in women of 80 years and older using the Prolift™ technique. IntUrogynecol J. 2010;21(12):1463–1470. | ||

Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1311–1316. | ||

Pizarro-Berdichevsky J, Clifton MM, Goldman HB. Evaluation and management of pelvic organ prolapse in elderly women. Clin Geriatr Med. 2015;31(4):507–521. | ||

Smith ARP, Kim J. Surgical treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. In: Graham SD Keane TE, editors. Glenn’s Urologic Surgery. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolter’s Kluwer; 2016:420–440. | ||

Danforth TL, Aron M, Ginsberg DA. Robotic sacrocolpopexy. Indian J Urol. 2014;30(3):318–325. | ||

Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol.1996;175:10–17 | ||

Kobashi K. Evaluation of patients with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. In: Wein AJ KL, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA, editors. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 10th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2012:1896–1908. | ||

Jelovsek JE, Maher C, Barber MD. Pelvic organ prolapse. Lancet. 2007;369(9566):1027–1038. | ||

Fitzgerald MP, Janz NK, Wren PA, et al. Prolapse severity, symptoms and impact on quality of life among women planning sacrocolpopexy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;98(1):24–28. | ||

Kobashi KC. Evaluation of patients with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. In: Campbell-Walsh Urology. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2012:1896–908. | ||

Winters JC, Dmochowski RR, Goldman HB, et al. Urodynamic studies in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2012;188(6 Suppl):2464–2472. | ||

Thiagamoorthy G, Cardozo L, Srikrishna S, Toozs-Hobson P, Robinson D. Management of prolapse in older women. Post Reprod Health. 2014;20(1):30–35. | ||

Hagen S, Stark D. Conservative prevention and management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011’(12):CD003882. | ||

Li C, Gong Y, Wang B. The efficacy of pelvic floor muscle training for pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2015. | ||

Griebling TL. Vaginal pessaries for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse in elderly women. Curr Opin Urol. 2016;26(2):201–206. | ||

Lone F, Thakar R, Sultan AH. One-year prospective comparison of vaginal pessaries and surgery for pelvic organ prolapse using the validated ICIQ-VS and ICIQ-UI (SF) questionnaires. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(9):1305–1312. | ||

Abdool Z, Thakar R, Sultan AH, Oliver RS. Prospective evaluation of outcome of vaginal pessaries versus surgery in women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(3):273–278. | ||

Greer JA, Northington GM, Harvie HS, Segal S, Johnson JC, Arya LA. Functional status and postoperative morbidity in older women with prolapse. J Urol. 2013;190(3):948–952. | ||

Greer JA, Harvie HS, Andy UU, Smith AL, Northington GM, Arya LA. Short-term postoperative functional outcomes in older women undergoing prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(3):551–558. | ||

Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(6):901–908. | ||

Richter HE, Redden DT, Duxbury AS, Granieri EC, Halli AD, Goode PS. Pelvic floor surgery in the older woman: enhanced compared with usual preoperative assessment. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(4):800–807. | ||

Miller KL. Operating on the elderly woman--what are her special needs? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1997;9(5):300–305. | ||

Nahhas WA, Brown M. Gynecologic surgery in the aged. J Reprod Med. 1990;35(5):550–554. | ||

Vetere PF, Putterman S, Kesselman E. Major reconstructive surgery for pelvic organ prolapse in elderly women, including the medically compromised. J Reprod Med. 2003;48(6):417–421. | ||

Schweitzer KJ, Vierhout ME, Milani AL. Surgery for pelvic organ prolapse in women of 80 years of age and older. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84(3):286–289. | ||

Krissi H, Aviram A, Ram E, Eitan R, Wiznitzer A, Peled Y. Colpocleisis surgery in women over 80 years old with severe triple compartment pelvic organ prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;195:206–209. | ||

Murphy M, Sternschuss G, Haff R, van Raalte H, Saltz S, Lucente V. Quality of life and surgical satisfaction after vaginal reconstructive vs obliterative surgery for the treatment of advanced pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(5):573.e571–e577. | ||

Barber MD, Amundsen CL, Paraiso MF, Weidner AC, Romero A, Walters MD. Quality of life after surgery for genital prolapse in elderly women: obliterative and reconstructive surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(7):799–806. | ||

FitzGerald MP, Richter HE, Siddique S, Thompson P, Zyczynski H, Network Ann Weber for the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Colpocleisis: a review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17(3):261–271. | ||

Sung VW, Weitzen S, Sokol ER, Rardin CR, Myers DL. Effect of patient age on increasing morbidity and mortality following urogynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(5):1411–1417. | ||

Krlin RM, Soules KA, Winters JC. Surgical repair of pelvic organ prolapse in elderly patients. Curr Opin Urol. 2016;26(2):193–200. | ||

Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: the OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023–1034. | ||

Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Marjoribanks J. Transvaginal mesh or grafts compared with native tissue repair for vaginal prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD012079. | ||

Nieminen K, Heinonen PK. Sacrospinous ligament fixation for massive genital prolapse in women aged over 80 years. BJOG. 2001;108(8):817–821. | ||

Toglia MR, Nolan TE. Morbidity and mortality rates of elective gynecologic surgery in the elderly woman. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(6):1584–1587; discussion 1587–1589. | ||

Stepp KJ, Barber MD, Yoo EH, Whiteside JL, Paraiso MF, Walters MD. Incidence of perioperative complications of urogynecologic surgery in elderly women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1630–1636. | ||

Bretschneider CE, Robinson B, Geller EJ, Wu JM. The effect of age on postoperative morbidity in women undergoing urogynecologic surgery. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21(4):236–240. | ||

Nygaard IE, McCreery R, Brubaker L, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a comprehensive review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(4):805–823. | ||

Clifton MM, Pizarro-Berdichevsky J, Goldman HB. Robotic female pelvic floor reconstruction: A review. Urology. 2015;91:33–40. | ||

Geller EJ, Siddiqui NY, Wu JM, Visco AG. Short-term outcomes of robotic sacrocolpopexy compared with abdominal sacrocolpopexy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(6):1201–1206. | ||

Serati M, Bogani G, Sorice P, et al. Robot-assisted sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Eur Urol. 2014;66(2):303–318. | ||

Geller EJ, Parnell BA, Dunivan GC. Robotic vs abdominal sacrocolpopexy: 44-month pelvic floor outcomes. Urology. 2012;79(3):532–536. | ||

Linder BJ, Chow GK, Elliott DS. Long-term quality of life outcomes and retreatment rates after robotic sacrocolpopexy. Int J Urol. 2015;22(12):1155–1158. | ||

Pan K, Zhang Y, Wang Y, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of conventional laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy versus robot-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016;132(3):284–291. | ||

De Gouveia De Sa M, Claydon LS, Whitlow B, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for treatment of prolapse of the apical segment of the vagina: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(3):355–366. | ||

Hsu RL, Kaye AD, Urman RD. Anesthetic challenges in robotic-assisted urologic surgery. Rev Urol. 2013;15(4):178–184. | ||

Bates AT, Divino C. Laparoscopic surgery in the elderly: a review of the literature. Aging Dis. 2015;6(2):149–155. | ||

Lavoué V, Gotlieb W. Benefits of minimal access surgery in elderly patients with pelvic cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2016;8(1). | ||

Rogers CG, Sammon JD, Sukumar S, Diaz M, Peabody J, Menon M. Robot assisted radical prostatectomy for elderly patients with high risk prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2013;31(2):193–197. | ||

Winters BR, Bremjit PJ, Gore JL, et al. Preliminary comparative effectiveness of robotic versus open radical cystectomy in elderly patients. J Endourol. 2016;30(2):212–217. | ||

Richards KA, Kader AK, Otto R, Pettus JA, Smith JJ, Hemal AK. Is robot-assisted radical cystectomy justified in the elderly? A comparison of robotic versus open radical cystectomy for bladder cancer in elderly ≥75 years old. J Endourol. 2012;26(10):1301–1306. | ||

Robinson BL, Parnell BA, Sandbulte JT, Geller EJ, Connolly A, Matthews CA. Robotic versus vaginal urogynecologic surgery: a retrospective cohort study of perioperative complications in elderly women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19(4):230–237. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.