Back to Journals » Clinical Interventions in Aging » Volume 11

Management of acute perioperative myocardial infarction: a case report of concomitant acute myocardial infarction and tumor bleeding in the transverse colon

Authors Li Y, Gao W, Li Y, Feng Q , Zhu P

Received 7 July 2015

Accepted for publication 13 October 2015

Published 18 February 2016 Volume 2016:11 Pages 159—166

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S91918

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Zhi-Ying Wu

Yu-Feng Li,1,* Wen-Qian Gao,2,* Yuan-Xin Li,3,* Quan-Zhou Feng,1,* Ping Zhu2

1The Department of Cardiology, Clinical Division of Medicine, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; 2The Department of Cardiology, Clinical Division of Nanlou, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, People’s Republic of China; 3Navy Wangshoulu Clinics, Beijing, People’s Republic of China

*These authors contributed equally to this work

Abstract: Acute myocardial infarction complicated by bleeding colon tumor is problematic with regard to management, and appropriate balance of antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy and hemostasis or surgery is crucial for effective treatment. Here, we present a case of concomitant acute myocardial infarction and bleeding tumor in the transverse colon, and share our experience of successfully balancing anticoagulation therapy and hemostasis.

Keywords: management, acute myocardial infarction, perioperative, antiplatelet, hemostasis

Introduction

Combination therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel, and anticoagulation agents plays an important role in the management of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), including unstable angina and acute myocardial infarction. Dual (aspirin plus clopidogrel) antiplatelet therapy should be prescribed for at least 4 weeks after ACS and up to 12 months after drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation to prevent in-stent thrombosis, according to American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines.1,2 However, in some patients, inappropriate use of antiplatelet and anticoagulation agents can result in life-threatening bleeding. Bleeding that occurs while patients are receiving dual or triple (aspirin plus clopidogrel and anticoagulation) therapy is a particularly intractable problem. The development of appropriate methods to balance antiplatelet therapy and bleeding may present a key to resolving this issue. Here, we report the successful implementation of an effective management strategy for an elderly male patient with acute myocardial infarction complicated by bleeding adenocarcinoma in the transverse colon.

Case presentation

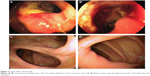

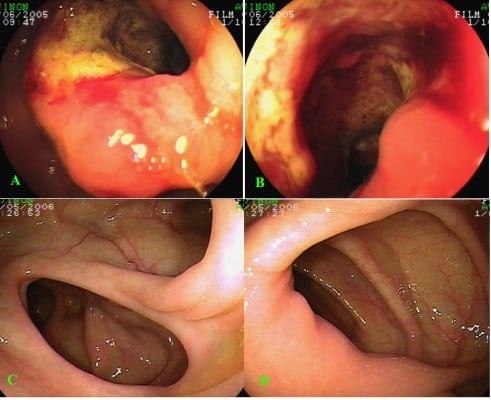

A 70-year-old Chinese man was referred to our hospital for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). He received antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy for 10 days because of non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) at the local hospital, but chest pain on exertion occurred repeatedly. Electrocardiogram (ECG) measurements showed ST segment slope-down depression and T-wave inversion on leads II, III, aVF, and V4–V6 (Figure 1). After admission, the patient continued to receive aspirin, clopidogrel (Plavix®, Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, NY, USA/Sanofi Bridgewater, NJ, USA), dalteparin sodium (FRAGMIN® injection [a low molecular weight heparin], Pfizer, Inc., New York, NY, USA), and omeprazole, (Astra Merck, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA) (a proton pump inhibitor). The stool occult blood test was positive following NSTEMI. Colonoscopy was performed to exclude gastrointestinal (GI) malignancy (Figure 2) 1 month after NSTEMI, leading to the detection of an infiltrating tumor (non-typical carcinoid in biopsy pathology) in the right segment of the transverse colon with three quarters colon wall involvement and cavity stenosis. Gastroscopy was performed 2 days later, with normal results.

To balance GI bleeding of colon tumor and cardiac conditions, the decision was made to perform PCI, followed by resection of the transverse colon. Coronary angiogram revealed focal proximal left anterior descending stenosis (60%), diffuse stricture (70%–85%) of proximal and middle circumflex, middle right coronary occlusion, 95% stenosis of the opening of the first sharp edge of the branch, and no significant left main stenosis (Figure 3). A 2.75/33 mm sirolimus-eluting stent (Cypher®, Cordis Corporation, Hialeah, FL, USA) was implanted in the right coronary lesions to prepare for abdominal surgery. ECG after stent implantation showed increasing T-wave amplitudes on leads V1–V3 and decreasing T-wave amplitudes on leads II, III, and aVF, compared with those on admission (Figure 1). The anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs administered after PCI included clopidogrel (75 mg/day) and dalteparin sodium (initially at a dose of 5,000 IU/12 hours, and 2 days later, 5,000 IU/24 hours).

In the early morning of day 6 after PCI, the patient complained of sweating and chest pain. ECG showed inverted T-waves on leads II, III, and aVF (Figure 4). Total CK, CK-MB, and cardiac TnT (cTnT) levels were significantly increased, HB levels decreased from 115 g/L to 79 g/L in 6 days, and the stool occult blood test was positive. Blood pressure fell to 77/40 mmHg. Acute inferior wall myocardial infarction combined with GI bleeding was diagnosed. Balancing severe GI bleeding and NSTEMI, clopidogrel therapy was continued, dalteparin sodium was replaced with unfractionated heparin (UFH), and transfusion and octreotide acetate (Sandostatin®, Novartis International AG, Basel, Switzerland) treatment were included as part of the therapeutic approach. However, the patient remained in an unstable condition. On day 9 after PCI, re-coronary angiography was performed because of recurrent chest pain and deteriorating ECG patterns showing increased T-wave amplitudes in leads III, aVF, and V1–V6 (Figure 4). The angiogram revealed stent thrombosis, and recanalization was performed with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) (Figure 3). After PTCA, ECG showed decreased T-wave amplitudes in leads II, III, and, aVF (Figure 4). The heart condition was gradually stabilized, and UFH continued until 1 day before surgery. Activated partial thromboplastin times were kept in 80–120 seconds, and 6 days later, clopidogrel and aspirin were discontinued until day 19 after surgery owing to recurrent GI bleeding.

To prevent severe bleeding of the colon tumor, a decision to perform a partial resection of the transverse colon was made. On day 29 after stent implantation, the patient underwent partial resection of the transverse colon under general anesthesia. Pathological results showed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma without lymphatic metastasis (Dukes’ stage B). In the afternoon, the patient complained of chest pain. ECG revealed obvious elevation of the ST segment in leads II, III, and aVF (Figure 5). Serum chemistry results showed CK-MB 40.3 U/L and cTnT 0.452 ng/mL, and recurrent acute inferior wall myocardial infarction was diagnosed. The patient received rigorous care, including continuous monitoring of blood pressure, heart rate, and blood oxygen saturation, and intensive medication aimed to induce coronary dilation (isosorbide dinitrate), reduce cardiac load and myocardial oxygen consumption, and improve myocardial energy metabolism (trimetazidine, creatine phosphate sodium) without anticoagulation and thrombolysis. Acute left heart failure occurred on days 2 and 3 after surgery. On the 3rd day after surgery, the patient began to receive UFH. Bloody stools developed, and HB dropped from 96 g/L to 87 g/L. HB returned to normal after discontinuing UFH, and blood transfusion. Ten days later, three consecutive stool occult blood tests showed negative results. The patient was subsequently treated with clopidogrel and aspirin. However, 1 day later, the stool occult blood test became positive, and consequently, anti-platelet drugs were immediately discontinued. Approximately 2 months later, aspirin (0.1 g/day) and clopidogrel (75 mg/day) were administered after a negative stool occult blood test. The patient recovered after 101 days of hospitalization. Ten months after the operation, repeated colonoscopy disclosed no active bleeding (Figure 2). The patient’s general condition was stable after 5 years of follow-up. This report has been approved by the Committee on Human Research of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital. Written informed consent was provided by the patient.

Discussion

Combinations of antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy are universally accepted for the treatment of ACS. Despite their proven benefits in reducing mortality rates, adverse ischemic events, short- and long-term complications of PCI, and other major adverse cardiac events,3 these drugs are inextricably linked to increased risk of bleeding.

GI bleeding is a main complication of ACS treated with dual or triple antithrombotic therapy. GI bleeding may occur simultaneously with ACS because of acute gastric stress ulcers, colonic ischemia, and GI tumors. Hemodynamic instability and stress associated with ACS may contribute to bleeding. Moreover, GI bleeding is more likely to occur in elderly patients. The strongest predictor of in-hospital GI bleeding is proposed to be age >70 years (odds ratio 2.79, 95% confidence interval 1.74–4.48, P<0.001).4

In our patient, ACS was complicated by a bleeding tumor in the transverse colon. Initially, bleeding presented as stool occult blood-positive, followed by bloody stool, which resulted in a drop in HB and blood pressure. The tumor was the original cause of the bleeding, and the therapy using antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents was the inducer.

Upon occurrence of GI bleeding, antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents should be discontinued in common practice, but early termination of therapy may result in re-occlusion of coronary artery and stent thrombosis in the setting of ACS and PCI. Therefore, effective management of antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy of patients with concomitant ACS and GI bleeding remains a dilemma.

In the situation that bleeding persists and anticoagulation therapy is required, there is limited information to guide therapy, and the benefits and risks of antiplatelet and anticoagulation agents must be re-evaluated. If the benefits outweigh the risks, antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy should be continued. Otherwise, therapy should be discontinued or the antithrombotic regimen altered to a single antiplatelet or anticoagulant agent. Blood transfusion may be administered to anemic patients. Proton pump inhibitors are recommended to prevent GI bleeding,5 but some, such as omeprazole, are reported to significantly decrease the inhibitory effect of clopidogrel on platelet aggregation.6,7 Octreotide is another choice of drug to treat GI bleeding.8

When GI bleeding occurred in our patient, aspirin and dalteparin were initially discontinued, in view of the finding that clopidogrel showed a favorable safety profile with fewer cases of GI bleeding and better gastric tolerability in a comparative trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischemic events.9 Although dalteparin was re-administered after stent deployment, subacute stent thrombosis was not prevented because of insufficient antithrombotic therapy, and GI bleeding deteriorated due to anticoagulation or stress associated with myocardial ischemia. In this setting, blood transfusion, omeprazole, and octreotide prevented further bleeding.

Perioperative management of non-cardiac surgery in patients with recently implanted coronary artery stents is another challenge for physicians. Premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery stents scheduled to undergo surgery increases the risk of stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction, and death. Therefore, increased emphasis has been laid on the prevention of premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy. The 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines10 recommend 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel for patients with DES implantation before elective non-cardiac surgery. If the surgery cannot be postponed, it is recommended that aspirin therapy is continued throughout the perioperative period, if possible, and clopidogrel therapy restarted as soon as possible after surgery. Moreover, management of perioperative antiplatelet therapy should be determined by consensus of the surgeon, anesthesiologist, cardiologist, and patient, weighing the relative risk of bleeding with that of stent thrombosis.

This patient was subjected to partial resection of the transverse colon on day 29 after stent implantation, and aspirin, clopidogrel, and UFH were discontinued throughout the perioperative period because of recurrent GI bleeding. Although stent re-thrombosis cannot be confirmed without angiography, acute myocardial infarction potentially resulting from stent thrombosis was observed soon after surgery. The patient gradually recovered after intensive care and maximal medication without PCI. Once again, it was demonstrated in our patient that non-cardiac surgery in patients recently receiving coronary stent implantation should be postponed as long as possible to reduce the risk of stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction.

Although the patient recovered, two controversial decisions were made. According to the 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines10 on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for non-cardiac surgery patients, revascularization before non-cardiac surgery is recommended in circumstances in which revascularization is indicated according to existing clinical practice guidelines11,12 and PCI should be performed in patients with unstable coronary artery disease who may be appropriate candidates for emergency or urgent revascularization. In these cases, balloon angioplasty or bare-metal stent implantation should be considered, but our patient underwent DES implantation. According to the guidelines, elective non-cardiac surgery should be optimally delayed 365 days after DES implantation. However, in our patient, bleeding from the colon tumor resulted in blood pressure fall and stress, further stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction, which was treated with antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy that aggravated tumor bleeding, leading to a vicious cycle. Furthermore, colon tumor without colectomy may be associated with tumor metastasis risk. Therefore, when the cardiac condition was stable, partial colectomy in this patient was performed on day 29 of DES implantation, which led to occurrence of myocardial infarction in the afternoon.

After the operation, the tumor was confirmed as a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in Dukes’ stage B. Partial colectomy disrupted the vicious bleeding-infarction-antithrombotic therapy-bleeding cycle. In the absence of tumor bleeding, antiplatelet and anticoagulation therapy efficiently prevented stent thrombosis and myocardial ischemia. Therefore, our patient recovered fully after the operation with no further bleeding or serious myocardial ischemia. The general condition of the patient was stable after 5 years of follow-up, validating the efficacy of the operation.

Conclusion

Management of patients with acute perioperative myocardial infarction is a considerable decision-making challenge for physicians. Hemorrhage and antithrombotic therapy should be balanced according to the benefits and risks of the regimen. Coronary intervention was performed first when both surgery and coronary intervention were necessary, and bare stents were preferred. This principle should be followed in practice. If non-cardiac surgery cannot be delayed, stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction will occur. Indispensable non-cardiac surgery that cannot be delayed may benefit the patient, although stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction may occur. When perioperative acute myocardial infarction complicated by hemorrhage occurs, intensive care and maximal medical therapy might help the patient survive.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships or conflicts of interest.

References

Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-Elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(7):e1–e157. | ||

Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127(23):e663–e828. | ||

Grines CL, Bonow RO, Casey DE Jr, et al. Prevention of premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery stents: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, American College of Surgeons, and American Dental Association, with representation from the American College of Physicians. Circulation. 2007;115(6):813–818. | ||

Abbas AE, Brodie B, Dixon S, et al. Incidence and prognostic impact of gastrointestinal bleeding after percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(2):173–176. | ||

Bhatt DL, Scheiman J, Abraham NS, et al. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(18):1502–1517. | ||

Gilard M, Arnaud B, Cornily JC, et al. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated with aspirin: the randomized, double-blind OCLA (Omeprazole CLopidogrel Aspirin) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(3):256–260. | ||

Sibbing D, Morath T, Stegherr J, et al. Impact of proton pump inhibitors on the antiplatelet effects of clopidogrel. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101(4):714–719. | ||

Chen RJ, Fang JF, Chen MF. Octreotide in the management of postoperative enterocutaneous fistulas and stress ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(9):1212–1215. | ||

Thizon-de-Gaulle I. Antiplatelet drugs in secondary prevention after acute myocardial infarction. Rev Port Cardiol. 1998;17(12):993–997. | ||

Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130(24):e278–e333. | ||

Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011;124(23):e574–e651. | ||

Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124(23):e652–e735. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.