Back to Journals » Pediatric Health, Medicine and Therapeutics » Volume 11

Magnitude of Dental Caries and Its Associated Factors Among Governmental Primary School Children in Debre Berhan Town, North-East Ethiopia

Authors Aynalem YA , Alamirew G, Shiferaw WS

Received 1 May 2020

Accepted for publication 26 June 2020

Published 20 July 2020 Volume 2020:11 Pages 225—233

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PHMT.S259813

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Roosy Aulakh

Yared Asmare Aynalem,1 Getu Alamirew,1,2 Wondimeneh Shibabaw Shiferaw1

1Department of Nursing, College of Health Science, Debre Berhan University, Debre Berhan, Ethiopia; 2Debre Berhan Referral Hospital, Debre Berhan, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Yared Asmare Aynalem

Department of Nursing, College of Health Science, Debre Berhan University, P.O. Box 445, Debre Berhan, Ethiopia

Email [email protected]

Background: In Ethiopia, oral health prevention and treatment have gotten low attention in the government, and the existing dental services are privately owned and thus expensive. Hence, this study aimed to assess the prevalence of dental caries and its associated factors among governmental primary school children in Debre Berhan town, Ethiopia, 2019.

Methods: An institutional-based cross-sectional study was conducted from January 30 to February 14/2019. A total of 417 primary school children were selected using computer-generated simple random sampling and interviewed using structured and pretested questionnaires. Data were coded, entered, and cleaned using Epi-data version 3.1 and export to SPSS version 22 for analysis. Binary logistic regression analysis was employed to test the association between dependent and independent variables. P-value less than 0.05 was taken as significant association. Finally, the result of this study was present by text, tables, and graphs.

Results: Out of the 396 study participants, 135 (34.1%) had dental caries. Of these, more than half, 95 (59.37%) had the pre-molar decayed. Two hundred eighty-five (72.0%) of them were cleaned their teeth. The Independent predictors of dental caries were drinking sugared tea [AOR= 2.034, 95% CI: (1.223– 3.385)] and food particle on their teeth [AOR= 6.709, 95% CI: (3.475– 12.954)], which had shown a significant association with dental caries.

Conclusion: The over magnitude of dental caries was relatively high and found to be a public health problem. Drinking sugar tea, presence of food particles, or dental plaque were significantly associated with dental caries. In contrast, merchant occupation reduced the chance of dental caries. Giving health education to minimize drinking sugar tea and cleaning their teeth after consumption of sugar tea should be given attention.

Keywords: dental caries, children, associated factors, Ethiopia

Background

Dental caries is one of the global oral health problems, which cause the destruction of the hard parts of a tooth by the interaction of bacteria and fermentable carbohydrate.1 Now a day dental caries are on the rise to become major public health problems worldwide, it is estimated that 2.4 billion people suffer from caries of permanent teeth and out of them around 486 million children suffer from caries of primary teeth.2 Dental caries has detrimental consequences on children’s quality of life by inflicting pain, premature tooth loss, undernutrition, and finally influences overall growth and development.3–6 Although poor oral health is not life-threatening, it causes tooth pain, eating impairment, the loss of tooth, delay language development, decrease educational concentration in school, and has a high financial burden on the families.7,8 In many countries, access to dental care is not equitable, leaving poor children and families underserved.9,10 Fortunately, it is preventable, with almost all risk factors modifiable. According to WHO guidelines the prevention and control approaches range from changing personal behavior to working with families and caregivers to public health solutions such as building health policies, creating supportive environments, and health promotion and orientation of health services towards universal health coverage.11

Dental caries is also a progressive infectious process with a multifactorial aetiology.12,13 Dental caries has high morbidity potential.7 The frequent intake of sweets, dry mouth, and poor oral hygiene increase the chances for cavities.14 The early childhood caries pattern changes at age three and begins to affect the first and second primary molars in developing countries including Ethiopia.15,16 The prevalence of dental caries among pre-school children of developed nations has been declining over the past few decades.17,18 However, it is still high among pre-schoolers of developing nations.19–21 Numerous studies have revealed the magnitude of dental caries was reported as 43.6% in Thailand,22 70.4% in china,23 63.4% in India,24 and 73% in Eastern Saudi Arabia.25

The burden of dental caries is increasing rapidly in low- and middle-income nations, and, is particularly severe among children living in deprived communities.26,27 The prevalence of dental caries in Africa was reported to be varied from 12.6% to 24.1% in Nigeria,28,29 43.3% in Kenya,30 and 30.5% in Sudan.31 A study done in Ethiopia indicated that dental caries was 21.8% in Bahir Dar,32 47.4% in Addis Ababa,33 36.3% in Gondar Town,34 and 48.5% in Finote Selam.10 Overall, dental caries may influence children’s development and their participation in important daily activities.6

According to the report of different study sex, age, dietary habits, education, and oral hygiene status are associated with an increased prevalence of dental caries.30,32,35 Likewise, the growing consumption of sugared foods in the developing world, poor tooth-brushing habits, poor oral hygiene, and low level of awareness about dental caries are some of the factors that increased the levels of dental decay.28,36-38 On the contrary, frequent tooth brushing was a lower chance of having decayed.5

To the best of our knowledge, in Ethiopia few studies about demographic and socio-economic variables as risk factors of dental caries had been published.33,34 However, oral health prevention and treatment have gotten low attention in the government and the existing dental services are privately owned and expensive. As the finding of previous studies shows, dental caries are the public health problem among school children and there was no published research on the magnitude of dental caries in primary school children in the study area. Therefore, the objective of this study was to assess the magnitude of dental caries and its associated factors among governmental primary school children in the Debre Berhan town, Ethiopia.

Patients and Methods

Study Design and Setting

An institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted from January 30 to February 14/2019. This study was conducted in Debre Berhan town primary school’s students. The Debre Berhan town is located in North Shoa Administrative Zone, Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia. It is located at a distance of 130 km, North East of Addis Ababa (capital city of Ethiopia), 682 km the capital city of Amhara regional state Bahir Dar. The total population size of the district was putted as 108,876 out of which 49,259 were male and 59,617 were female.39 The town had 10 governmental primary schools, and the total numbers of primary school students were 7198 students, out of these the study subjects was 3607 students.40

Study Participants

Children from governmental primary school students who are grades 1–8, present in school during the data collection period, those living in Debre Berhan town for at least six months and consent to participate were included in the study. Aged greater than or equal to18 years, those who were mentally ill and unable to hear were excluded from the study.

Sample Size Estimation

The sample size was calculated using a single population proportion formula with an assumption of 95% confidence level, 5% degree of precision, and the proportion of dental caries, 21.8%.32 After adding a 10% non-response rate and 1.5 designs effects the final sample size of the study was 417.

Sampling Procedure

Our study sample was obtained by a two-stage cluster sampling technique. In the first stage, out of ten governmental primary schools, four schools were selected by using a simple random sampling technique and the sample size was allocated proportionally to each selected school, based on the number of students. In the second stage, the study participants were selected from each grade and sections of the selected schools by a simple random sampling technique using a computer-generated method proportionally to the number of students in each and sections. A list of the students were taken from their rosters in the respective class.

Data Collection

A structured questionnaire prepared in English was developed from different previous similar literatures10,32,36,41 which contain socio-demographic data, and factors associated with dental caries. A face-to-face interview was used to collect the data. To ensure the quality of the data, the questionnaire was initially developed in English and translated into local language, Amharic by experts and then back to English. Before going to the actual data collection, the questionnaire was pretested in a similar setting outside the study district 5%21 in model kutir 1 primary school to increase the validity and reliability of data collection tools. The questionnaire was modified based on the response after the pre-tested and modification was made in the final version of the data collection tool. The training was given to data collectors and supervisors for one day before the actual data collection task and trained guide was prepared to facilitate the training. Other than the outcome variables the data were collected from 5 BSC nursing students. All data collectors were trained on their responsibilities for the purposes of the study, how to collect the data, how to maintain confidentiality, and how to ensure genuine replies to questions. Lastly, the principal investigator was strictly following the overall activities of the data collection on a daily base to ensure the completeness of the questionnaire and to give further clarification.

A Dental Examination

It was carried out for all selected children by one trained dental doctor using World Health Organization (WHO) dental caries diagnosis guideline with the Decayed, Missed, filled Tooth (DMFT) index under natural daylight.42 A tooth was recorded as decayed when a carious lesion or both carious lesions and a restoration are present at enamel or detectably softened wall or floor. It was also recorded as missing when it has been extracted due to caries and a permanent or temporary filling is present, or when a filling is defective but not decayed is counted as a filled tooth. The intra examiner agreement was evaluated by re-assessing a 10% random sample of the children on the same day. The dental assistant without the knowledge of the examiner performed the selection of children for duplicates.

Data Processing and Analysis

Data were coded, cleaned, entered, and edited using Epi-data version 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 22 for analysis. Descriptive statistics, like frequency and percentage, were used depending on the nature of the variable. All variables, which become significant with a p-value of ≤0.25 in the bivariable analysis was fitted into the multivariable logistic regression. Variables with a p-value of ≤0.05 at multivariable analysis were considered as significantly associated with the outcome variable. In the model variable section technique was successive stepwise backward elimination. Confounding and effect modification was checked by looking at regression coefficient change greater than or equal to 15% and multi-collinearity was checked using the variance inflation factor using a value of <10 as a cut-off point. Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to see the strength of the association between dependent and independent variables. Finally, the finding of the study was displayed by using texts, tables, and figures.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants

A total of 417 eligible primary school students were interviewed with a nearly 95% response rate. The mean age of participants was 12.74 (SD±2.556) with a range of 11–14 years old. More than half, 218 (55.1%) of students were females. Nearly half, 197 (49.71%) of students were 11–14 ages. Most of the study participants 293 (74%) of the respondents were married. Regarding the residency majority of participants, 334 (84.3%) was urban (Table 1).

|

Table 1 Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participant in Debre Berhan Town, Ethiopia, 2019 |

Food Consumption Pattern, Dietary Habits and Practices Related to Oral Hygiene

According to our study, most 307 (77.5%) of the students were getting meals three times per day. Fifty-four (13.6%) of the participants drank coffee with sugar. Most, 307 (77.5%) of the students were drank soft drinks. One hundred twenty-nine (32.6%) of the study participant were eating sweet food. Majority 373 (94.2%) of the student often uses sweet food and drinks. In our study most, 285 (72.0%) of them were cleaned their teeth. Out of them, 15 (5.62%) cleaned teeth after every meal. However, nearly half 132 (46.32%) of children cleaned their teeth once per day. Similarly, nearly half 140 (49.12%) of children were cleaned their teeth morning. Among the participants, 128 (44.91%) of them were used toothbrush with paste. However, 122 (42.81%) and 33 (11.58%) were used toothbrush with media and only a toothbrush, respectively to clean their tooth (Table 2)

|

Table 2 Consumption Pattern, Dietary Habits, and Practice Related to Oral Hygiene of the Study Participants in Debre Berhan Town, Ethiopia, 2019 |

Magnitude of Dental Caries

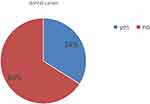

Out of the 396 study participants, 135 (34.1%) had dental caries (Figure 1). More than half, 95 (59.37%) of the students had pre-molar dental carries. According to our study, 28 (7.1%) had missed teeth. Of these, nearly half 12 (42.86%) of the missed teeth was pre-molar.

|

Figure 1 Prevalence of dental caries of study participant in Debre Berhan town, Ethiopia,2019. |

Factors Associated with Dental Caries

According to this study, children who drank sugared tea frequently had 2 times [AOR=2.03% CI: (1.22; 3.38]) a chance of developing dental caries than those who drank sugared tea rarely. Similarly, students who had food particles on their teeth were 7 times [AOR= 6.70, 95% CI: (3.47; 12.95)] more likely to develop dental caries than those who did not have food particle on their teeth. However, dental caries among children, whose parents’ occupation of a merchant was 53% [AOR= 0.47, 95% CI: (0.240.91)] less likely chance of developing dental caries compared to those who had a private worker parent. On the other hand, students who ate sweet foods at any time point during the study period were 57.8% less likely [AOR= 0.42, 95% CI: (0.24; 0.71)] to develop dental caries than those who does no ate sweet foods, and we are 95% confident that the true value is lying between 29% and 76% (Table 3). No confounding, effect modification, and multi-collinearity were observed in this study.

|

Table 3 Factors Associated with Dental Caries of Study Participant in Debre Berhan Town, Ethiopia, 2019 |

Discussion

The current study was aimed to assess the magnitude of dental caries and its associated factors among governmental primary school children in Debre Berhan town, northeast Ethiopia. According to this study, the magnitude of dental caries among school children was 34.1%. Our finding was in line with a study done in the Tigray region (35.4%).43 However, the result was higher than studies conducted in Bahir Dar (21.8%),32 Nigeria (24.1%),28 Sudan (30.3%),31 and Pakistan 14.5%.44 But lower than other studies in Kenya 43.3%30 and Finote-Selam (48.5%),10 Saudi Arabia (83%)45 ad Eretria (78%).46 The possible explanation about the variations might be the dental health consideration and the awareness level of most of the Ethiopians; including Debre-Berhan town school students is low. Another possible explanation might be the different study area and period.

Based on this study, the prevalence of dental caries was higher in male students 61 (34.27%) than females 74 (33.9%). This result was not supported by the studies done in Bahir Dar,28 Finote-Salam32, and in Kenya.30 This discrepancy might be due to other co-founding factors like brushing habits and dietary habits.

According to the present study, the magnitude of dental caries among participants aged group 7–10 was 34 (36.56%). In line with a study conducted, in Bahir Dar, the proportion of dental caries was 33.3%32 in children from 6 to 10 years of age. The magnitude of dental caries was 47 (35.9%) among grade 1–4 students. Our finding is higher than a study in Bahir Dar the proportion of dental caries was 23 (31.9%) and 9(12.2%) among children from grades 1–4 and 5–8, respectively. The possible reason might be when the age and education level increases the awareness about dental caries and oral health may be increased.

Concerning the residence in this study, the students who were living in rural 25 (40.32%) had a higher prevalence than urban area 110 (33%). This finding was supported by studies done in Zimbabwe47. However, this result was not inlined with Finote-Selma’s study and in Uganda.10,48 The possible reason may be the awareness of oral hygiene in rural is low.

According to the current study, 128 (32.2%) children used a toothbrush with paste to clean their teeth, whereas 122 (30.8%) children used a traditional small stick of wood (termed as Mafaqiya) made of a special type of plant to clean their teeth. However, the study done in Bahir Dar city reported that 67.6% of children cleaned their teeth using a traditional small stick of wood (Mafaqiya) for maintaining oral hygiene.32 This might be due to the poor habit and improper usage of the tooth-brushing sticks in the country.

Recent studies showed that more than half, 95 (59.37%) of the respondents had the pre-molar decayed and 28 (7.1%) had missed teeth. Out of them about nearly half, 12 (42.86%) of missed teeth were pre-molar. This finding is in line with a study done in Finote-Selam study, dental caries was most prevalent in premolar (42.2%).10 Besides, this result is in line with a study done in Nigeria, which reported (46.5%).28 This might be due to its first eruption and main role in mastication.

Based on the current study, dental caries among not brush teeth were 41 (36.9%). Our finding was lower than a study in Finote-Selam 76.9% of students never brush their teeth had dental caries.10 This variation might be an awareness gap, study area, and period. The current study showed that children’s parents with occupations of merchants were 53% less likely to develop dental caries compared to those private workers. However, in another study no association between parent occupation and dental caries. Hence, further study is needed to be conducted to investigate the possible association of occupation and dental caries.

According to this study, students who drinking sugared tea frequently were 2 times more likely to develop dental caries than those who drinking sugared tea rarely. This result was not supported by other studies.10,32 This variation might be due to the different habits of drinking sugared tea across different areas and in the current study, most participants did not brush their teeth after drinking sugared tea.

The current study reported that students who have food particles or plaque on their teeth were 7 times more likely to develop dental caries than those who did not have food particles on their teeth. This finding is in line with a study done in Bahir Dar.32 According to this study, students who eat sweet foods frequently found to be 2.4 more likely to develop dental caries than those who use sugared foods sometimes. This study is in line with, the study conducted in Finote-Selam,10 and Kenya.30

These research findings would provide important baseline information and evidence regarding the overall magnitude of dental caries and its associated factors. Despite extensive efforts, the result of this study is subject to certain limitations; first, the cross-sectional nature of the study design impossible to form causal relationships between exposure and outcome variables. Second, behaviour aspects of the children cannot understand merely by the quantitative study. Third, the detection of dental caries using dental mirrors and radiology was not possible because of a lack of instruments and laboratory setup.

Conclusion

The over the magnitude of dental caries was relatively high. Drinking sugar tea, presence of food particle, or dental plaque was found to be significantly associated with dental caries. In contrast, merchant occupation.

Abbreviations

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; COR, crude odds ratio; SPSS, Social Package Statistically Software; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

All relevant data are in the manuscript. However, the minimal data underlying all the findings in the manuscript are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics and Consent Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Debre Berhan University, Institute of Medicine, and College of Health Sciences Ethical Board. A letter of permission was obtained from the Department of Paediatrics and Child Health Nursing. After that permission was obtained from the Debre Berhan Town Education Bureau and each primary school. Informed verbal consent was obtained from all study participants before the interview. Confidentiality of the information was ensured throughout the study.

Consent

The authors confirm that all caregivers provided informed consent forms. Debre Berhan University approved the verbally informed consent process with the approval number of Ref.no. DBU.R.D 126/2011.

Acknowledgments

Our first thanks go to the Debre Berhan University for funding this paper. The authors express their appreciation to the Debre Berhan Town Education Bureau, particularly the school directors for their kind cooperation during data collection. The authors are grateful to study participants and data collectors.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

1. report W. 2015. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs318/en.

2. Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–1259. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2

3. Dawkins E, Michimi A, Ellis-Griffith G, Peterson T, Carter D, English G. Dental caries among children visiting a mobile dental clinic in South Central Kentucky: a pooled cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2013;13(1):19. doi:10.1186/1472-6831-13-19

4. Abanto J, Paiva SM, Raggio DP, Celiberti P, Aldrigui JM, Bönecker M. The impact of dental caries and trauma in children on family quality of life. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40(4):323–331. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.2012.00672.x

5. Damyanov ND, Witter DJ, Bronkhorst EM, Creugers NH. Dental status and associated factors in a dentate adult population in Bulgaria: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Dent. 2012;2012.

6. Adulyanon S, Sheiham A. Oral impacts on daily performances. Meas Oral Health Qual Life. 1997;151:160.

7. Moses J, Rangeeth B, Gurunathan D. Prevalence of dental caries, socio-economic status, and treatment needs among 5 to 15-year-old school-going children of Chidambaram. J Clin Diagn Res. 2011;5(1):146–151.

8. Zhang S, Liu J, Lo EC, Chu C-H. Dental caries status of Bulang preschool children in Southwest China. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14(1):16. doi:10.1186/1472-6831-14-16

9. Syed S, Gangam S, Syed S, Rao R. Morbidity patterns and its associated factors among school children of an urban slum in Hyderabad, India. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2015;4(9):1277–1282. doi:10.5455/ijmsph.2015.30032015264

10. Teshome A, Yitayeh A, Gizachew M. Prevalence of dental caries and associated factors among Finote Selam primary school students aged 12–20 years, Finote Selam town, Ethiopia. Age. 2016;12(14):15–17.

11. Moynihan P, Makino Y, Petersen PE, Ogawa H. Implications of WHO guideline on sugars for dental health professionals. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2018;46(1):1–7. doi:10.1111/cdoe.12353

12. e Franco F, Costa TC, Amoroso P, Marin JM, Ávila F. Detection of streptococcus mutants and streptococcus sobrinus in dental plaque samples from Brazilian preschool children by a polymerase chain reaction. Braz Dent J. 2007;18(4):329–333. doi:10.1590/S0103-64402007000400011

13. Garcia-Closas R, Garcia-Closas M, Serra-Majem L. A cross-sectional study of dental caries, intake of confectionery and foods rich in starch and sugars, and salivary counts of Streptococcus mutans in children in Spain. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66(5):1257–1263. doi:10.1093/ajcn/66.5.1257

14. R: AV. Dental caries talking with patients. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2004;16(1):76. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8240.2004.tb00460.x

15. Brodeur J-M, Galarneau C. The high incidence of early childhood caries in kindergarten-age children. J Coll Dent Quebec. 2006.

16. Hallett KB, O’Rourke PK. Pattern and severity of early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34(1):25–35. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00246.x

17. Pitts N, Chestnutt I, Evans D, White D, Chadwick B, Steele J. 1 verifiable CPD paper: the dentinal caries experience of children in the United Kingdom, 2003. Br Dent J. 2006;200(6):313. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4813377

18. Hugoson A, Koch G. Thirty-year trends in the prevalence and distribution of dental caries in Swedish adults (1973–2003). Swed Dent J. 2008;32(2):57–67.

19. Wyne A. Caries prevalence, severity, and pattern in preschool children. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008;9(3):24–31. doi:10.5005/jcdp-9-3-24

20. Askarzadeh N, Siyonat P. The prevalence and pattern of nursing caries in preschool children of. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2004;22(3):92–95.

21. Begzati A, Meqa K, Siegenthaler D, Berisha M, Mautsch W. Dental health evaluation of children in Kosovo. Eur J Dent. 2011;5(1):32. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1698856

22. Prismasari S, Thitasomakul S. Factors associated with dental caries of permanent first molars among Thai primary schoolchildren. Walailak J Sci Tech. 2018;16(8):535–543.

23. Zhou N, Zhu H, Chen Y, et al. Dental caries and associated factors in 3 to 5-year-old children in Zhejiang Province, China: an epidemiological survey. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19(1):9. doi:10.1186/s12903-018-0698-9

24. Maj Saravanan S, Lokesh S, Polepalle T, Shewale A. Prevalence, severity, and associated factors of dental caries in 3–6-year-old children–a cross-sectional study. Int J. 2014;2(6A):5–11.

25. Farooqi FA, Khabeer A, Moheet IA, Khan SQ, Farooq I, ArRejaie A. Prevalence of dental caries in primary and permanent teeth and its relation with tooth brushing habits among schoolchildren in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2015;36(6):737. doi:10.15537/smj.2015.6.10888

26. Petersen PE. The world oral health report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century–the approach of the WHO global oral health programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(s1):3–24. doi:10.1046/j.2003.com122.x

27. Woan J, Lin J, Auerswald C. The health status of street children and youth in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review of the literature. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(3):314–321e312. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.03.013

28. Udoye C, Aguwa E, Chikezie R, Ezeokenwa M, Jerry-Oji O, Okpaji C. Prevalence and distribution of caries in the 12–15 year urban school children in Enugu, Nigeria. Internet J Dent Sci. 2009;7(10):5580.

29. Eigbobo JO, Alade G. Dental caries experience in primary school pupils in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Sahel Med J. 2017;20(4):179. doi:10.4103/smj.smj_70_15

30. Kassim B, Noor M, Chindia M. Oral health status among Kenyans in a rural arid setting: dental caries experience and knowledge on its causes. East Afr Med J. 2006;83(2):100–105. doi:10.4314/eamj.v83i2.9396

31. Nurelhuda NM, Trovik TA, Ali RW, Ahmed MF. Oral health status of 12-year-old schoolchildren in Khartoum state, Sudan; a school-based survey. BMC Oral Health. 2009;9(1):15. doi:10.1186/1472-6831-9-15

32. Mulu W, Demilie T, Yimer M, Meshesha K, Abera B. Dental caries and associated factors among primary school children in Bahir Dar city: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7(1):949. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-949

33. Berhane HY, Worku A. Oral health of young adolescents in Addis Ababa—a community-based study. Open J Prev Med. 2014;4(08):640. doi:10.4236/ojpm.2014.48073

34. Ayele FA, Taye BW, Ayele TA, Gelaye KA. Predictors of dental caries among children 7–14 years old in Northwest Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2013;13(1):7. doi:10.1186/1472-6831-13-7

35. Okoye L, Ekwueme O. Prevalence of dental caries in a Nigerian rural community: a preliminary local survey. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2011;1(2):187–196.

36. Petersen PE. Improvement of the global oral health-the the leadership role of the World Health Organization. Community Dent Health. 2010;27(4):194–198.

37. Punitha V, Amudhan A, Sivaprakasam P, Rathanaprabu V. Role of dietary habits and diet in caries occurrence and severity among urban adolescent school children. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(Suppl 1):S296. doi:10.4103/0975-7406.155963

38. Leme AP, Koo H, Bellato C, Bedi G, Cury J. The role of sucrose in cariogenic dental biofilm formation—new insight. J Dent Res. 2006;85(10):878–887. doi:10.1177/154405910608501002

39. comition DBtAp. Debre Berhan Town, Annual Report of Debre Birhan Town Administration Plan Commission. Amhara Region, Ethiopia; 2018.

40. bureau DBtAe. Annual Registration of Debre Birhan Town Administration Education Bureau. Amhara Region, Ethiopia; 2018.

41. Oliveira ER, Narendran S, Williamson D. Oral health knowledge, attitudes, and preventive practices of third-grade school children. Pediatr Dent. 2000;22(5):395–400.

42. Organization WH. World Health Organization Oral Health Surveys–Basic Methods. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997.

43. Zeru T. Prevalence of dental caries and associated factors among Aksum primary school students, Aksum Town, Ethiopia 2019: a cross-sectional. Of. 2019;5:2.

44. Umer MF, Farooq U, Shabbir A, Zofeen S, Mujtaba H, Tahir M. Prevalence and associated factors of dental caries, gingivitis, and calculus deposits in school children of Sargodha district, Pakistan. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2016;28(1):152–156.

45. Alhabdan YA, Albeshr AG, Yenugadhati N, Jradi H. Prevalence of dental caries and associated factors among primary school children: a population-based cross-sectional study in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Environ Health Prev Med. 2018;23(1):60. doi:10.1186/s12199-018-0750-z

46. Andegiorgish AK, Weldemariam BW, Kifle MM, et al. Prevalence of dental caries and associated factors among 12 years old students in Eritrea. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17(1):169. doi:10.1186/s12903-017-0465-3

47. Mafuvadze BT, Mahachi L, Mafuvadze B. Dental caries and oral health practice among 12 year old school children from low socio-economic status background in Zimbabwe. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;14. doi:10.11604/pamj.2013.14.164.2399

48. Wandera M, Twa-Twa J. Baseline survey of oral health of primary and secondary school pupils in Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2003;3(1):19–22.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.