Back to Journals » Journal of Pain Research » Volume 12

Locally Delivered Flurbiprofen 8.75 mg for Treatment and Prevention of Sore Throat: A Narrative Review of Clinical Studies

Authors de Looze F , Shephard A, Smith AB

Received 2 July 2019

Accepted for publication 7 November 2019

Published 27 December 2019 Volume 2019:12 Pages 3477—3509

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S221706

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Dr Michael A Ueberall

Ferdinandus de Looze,1 Adrian Shephard,2 Adam B Smith3

1Data Health Australia Pty Ltd (AusTrials), Sherwood, QLD 4075, Australia; 2Category Development Organisation, Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare Ltd, Slough, Berkshire SL1 3UH, UK; 3Evidence Generation and Clinical Research, Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare Ltd, Hull, HU8 7DS, UK

Correspondence: Adrian Shephard

Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare Ltd, Turner House, 103–105 Bath Road, Slough, Berkshire SL1 3UH, UK

Tel +44 1753 217 800

Email [email protected]

Background: Antibiotics are inappropriately prescribed to many people with sore throat. As most cases of sore throat are viral and/or self-limiting, guidelines recommend symptomatic management as first-line treatment. This paper reviews the available clinical evidence for the efficacy and safety of low-dose (8.75 mg) flurbiprofen, locally delivered to the throat for the symptomatic management of pharyngitis/sore throat.

Method: A literature search was performed on 27 February 2019 using PubMed. Studies that met the following criteria were included in a narrative review: (1) studies evaluating the effectiveness of flurbiprofen for pharyngitis/sore throat; (2) randomized controlled studies; (3) locally administered formulation of study drug/comparator; and (4) flurbiprofen administered at 8.75 mg dose (single- or multiple-dose administration).

Results: A total of 17 papers were included in the review: 15 publications reporting data from nine unique clinical studies of flurbiprofen for acute pharyngitis, and two reporting studies of flurbiprofen for the prevention of postoperative sore throat (POST). Studies in acute pharyngitis demonstrated that single- and multiple-dose flurbiprofen 8.75 mg, locally administered in lozenge, spray or microgranule form, was well tolerated and provided early onset and long-lasting symptomatic relief from throat pain and soreness, sensation of swollen throat, difficulty swallowing, and other associated symptoms. This included patients with more severe symptoms, patients with confirmed Streptococcus A/C sore throat, and patients taking concomitant antibiotics. In addition, a single preoperative dose of flurbiprofen lozenge was shown to be effective for relieving early POST in patients undergoing general anesthesia.

Conclusion: Locally administered, low-dose flurbiprofen offers a useful first-line treatment option for symptomatic relief in patients with “uncomplicated” acute pharyngitis/sore throat associated with upper respiratory tract infection, thus potentially helping to reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescribing. It also offers an effective preoperative treatment option for the reduction of early POST severity and incidence.

Keywords: flurbiprofen, pharyngitis, sore throat, lozenge, spray, pain relief

Introduction

Pharyngitis is one of the most common reasons patients seek advice from a healthcare provider (HCP) in primary care.1 Although not life-threatening, pharyngitis, particularly symptoms such as sore throat, can have a substantial negative impact on an individual’s daily life.2 Relief from the severe symptoms of pharyngitis are a key driver of patients’ consultations with HCPs, and of antibiotic-seeking behavior,3,4 with complaints of sore throat constituting between 1% and 4% of all primary care presentations internationally.5,6 Pharyngitis is generally of infectious etiology, with the vast majority of cases caused by self-limiting viral infections.7 Only around 5–30% of cases are attributed to bacterial etiologies – with approximately 10% to group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes (strep A)7–10 – although other bacteria, including Streptococcus dysgalactiae (strep C), have been implicated.9 Pharyngitis symptoms typically last 3–7 days,11 but are often worst during the first few days.12,13 The natural course of pharyngitis is similar in most patients, regardless of whether they are strep positive or not.14

Guidelines recommend symptomatic management of pharyngitis as a first-line treatment, and suggest avoiding or delaying antibiotic use in acute pharyngitis, except in the minority of patients with more severe strep infection or risk factors for serious complications such as rheumatic fever.15,16 The availability of rapid and effective symptomatic relief is, therefore, an important factor in meeting patients’ expectations and avoiding unnecessary use of antibiotics;3 most cases of pharyngitis can be managed by patients using over-the-counter (OTC) treatments as a means of controlling their symptoms.15,16 As inflammation is the underlying cause of pharyngitis,12 treatment of the condition with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) can offer rapid and long-lasting relief from pain.17,18

To minimize the potential risk of an adverse event, regulatory bodies and medical societies recommend using the lowest effective NSAID dose for the shortest time necessary to control symptoms.19 Locally administered formulations of NSAIDs, such as lozenges and sprays, facilitate targeted application of active ingredient to the throat,20 allowing absorption of the drug directly where it is needed.21 This allows administration of a lower dose than systemic therapy,22 reducing the potential for adverse effects.23,24 Flurbiprofen is an NSAID that has been formulated for local delivery at a low dose and is commercially available as a single active ingredient in both lozenge and spray formulations.25,26 It is most commonly used at a dose of 8.75 mg, based on the results of a dose-ranging study that demonstrated linear dose–response relationships for effectiveness and adverse events at doses between 5.0 mg and 12.5 mg.27 Its use for the symptomatic relief of pharyngitis of viral, bacterial, or unknown etiology has been assessed in a number of studies.17,22,25,26,28–38 It has also been evaluated for the relief of postoperative sore throat POST,39–41 a common complication of general anesthesia42 and tonsillectomy43 that can negatively impact patients’ postoperative comfort.

The aim of this paper is to review the available clinical evidence for the efficacy and safety of low-dose (8.75 mg) flurbiprofen, locally delivered to the throat for the symptomatic management of pharyngitis/sore throat. This review predominantly focuses on the management of sore throat associated with upper respiratory tract infection (URTI); its use for POST prevention is discussed in brief.

Methods

Search Strategy

A literature search was performed on 27 February 2019 using PubMed (including MEDLINE), with a search string including the following: “flurbiprofen” [MeSH term] AND (“pharyngitis” [MeSH term] OR (“sore” [all fields] AND “throat” [all fields]) OR “sore throat” [all fields] OR “postoperative” [all fields]). No date limits were applied. The titles and abstracts of the retrieved references were screened against the following predefined inclusion criteria:

- Studies evaluating the effectiveness of flurbiprofen for pharyngitis/sore throat

- Randomized controlled studies

- Locally administered formulation of study drug/comparator

- Flurbiprofen administered at 8.75 mg dose (single- or multiple-dose administration)

The full text of all potentially relevant publications was then reviewed to confirm inclusion and to determine whether a meta-analysis of the data was feasible. If a meta-analysis was not deemed possible, a narrative review of the evidence would be performed.

Results

The PubMed search identified 33 unique records, of which 15 were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria based on title/abstract screening (Figure 1). A total of 18 records underwent full text assessment: 17 were selected for inclusion in the final review (Table 1), and one study in POST was excluded as it evaluated a flurbiprofen dose lower than 8.75 mg.39

|  |  |

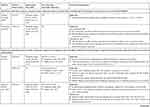

Table 1 Summary of Studies Included in the Narrative Review |

In view of the heterogeneity of the data reported in the studies identified, it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis. For example, studies varied with regard to the formulation by which the active ingredient was administered (lozenge, spray, and microgranules), the outcome measures investigated, the nature of data reported (some studies reported baseline and endpoint data, whereas others only reported efficacy in terms of percentage change from baseline) and the data reporting units. A narrative review was therefore determined to be the appropriate methodology.

Acute Pharyngitis

Fifteen publications, reporting data from nine unique clinical studies of flurbiprofen for acute pharyngitis, were included in this review (Table 1). Ten publications reported data for flurbiprofen lozenges vs placebo, two reported data for flurbiprofen spray vs placebo, two compared flurbiprofen lozenges and spray, and one reported data for flurbiprofen microgranules vs placebo. All flurbiprofen study medications were provided by Reckitt Benckiser. All studies included adult patients with confirmed pharyngitis due to URTI, with the exception of one study including patients aged 12 years and over which did not specifically screen for URTI.31 Patients were eligible for inclusion if they reported acute onset of pharyngitis (range: 3–7 days or less) and moderate to severe symptoms. The effectiveness of flurbiprofen has been assessed using several different outcome measures; Table 2 provides descriptions of the key endpoint measures and tools used in the included studies.

|

Table 2 Summary of Key Assessment Tools Used in the Included Studies |

Throat Pain and Soreness

Overall, flurbiprofen 8.75 mg generally provided significant relief of sore throat pain and soreness compared with placebo (Table 3), as measured on the Sore Throat Pain Intensity Scale (STPIS), Sore Throat Relief Rating Scale (STRRS), Throat Soreness Scale (TSS) and Sore Throat Scale (STS) (Table 2).

| ||

| ||

| ||

|

Table 3 Summary of Studies Reporting Throat Pain and Soreness Outcomesa |

Fourteen papers reported data on the effectiveness of single-dose flurbiprofen 8.75 mg for relieving throat pain and soreness;17,22,25,26,28–35,37,38 11 included data for flurbiprofen lozenges, four for flurbiprofen spray and one for flurbiprofen microgranules. In a study by Schachtel et al,17 single-dose flurbiprofen lozenge demonstrated a significantly greater reduction (85%) in sore throat pain intensity summed over the 2 h post-dose period (as measured on the STPIS) compared with placebo (p<0.001). Moreover, in another study by Schachtel et al,35 almost all (97%) patients treated with a single flurbiprofen lozenge experienced a reduction in sore throat pain intensity over the 3 h post-dose period (vs 76% of placebo-treated patients; p<0.01). Several other papers also reported significantly greater reductions in sore throat pain intensity compared with placebo with single-dose flurbiprofen lozenge,29,30,37 spray,34 and microgranules38 for up to 3–6 h post-dose (specific percentage reductions were not provided). Regarding absolute/percentage reductions in sore throat pain intensity/soreness from baseline, significantly greater reductions were observed with flurbiprofen vs placebo at all individual timepoints up to 2–4 h in several studies.17,22,29–35,37 Radkova et al26 observed an STPIS pain intensity difference from baseline to 2 h post-dose of −40.51 and −40.10 with flurbiprofen spray and lozenges, respectively. No significant difference was observed between single-dose flurbiprofen spray and lozenge in terms of improvement in sore throat pain intensity.25,26

With regard to relief of sore throat (as measured on the STRRS), Schachtel et al17 reported significantly greater relief with flurbiprofen lozenge vs placebo at all time points from 1‒4 h (all p<0.05). Burova et al25 observed that 74–78% of patients experienced “at least moderate relief” by 2 h post-dose with flurbiprofen lozenge or spray, and 98% experienced “slight” relief over the same period. In the study by Schachtel et al,17 the sum of total pain relief scores (TOTPAR), calculated from the STRRS, was 82% greater with flurbiprofen lozenge compared with placebo over the 1–2 h post-dose period (p<0.001), with 53% of patients taking flurbiprofen experiencing “at least moderate relief” (compared with 26% of placebo patients; p<0.001). Several other studies have also reported significantly greater improvements in sore throat relief with single-dose flurbiprofen (lozenges, spray or microgranules) vs placebo for between 2 and 6 hrs post-dose.32,34,38

Radkova et al26 and Burova et al25 reported similar efficacy of single-dose flurbiprofen spray and lozenge for sore throat relief. One paper, by Watson et al,22 failed to demonstrate a significant improvement in TOTPAR over 2 h vs placebo, although a trend in favor of flurbiprofen lozenge was observed (p=0.06). However, analysis of sore throat relief at individual time points revealed significant differences in favor of flurbiprofen compared with placebo at 45, 60, and 75 min (p<0.05).

Significant reductions in throat soreness (as measured on the TSS and STS) have also been observed with single-dose flurbiprofen across all studies reporting these measures, ranging from 23% to 124% greater reductions in throat soreness vs placebo over 2 h, where numerical data are reported.22,28,31,32,34,38

Eight of the papers have provided clinical evidence that multiple-dose flurbiprofen, taken every 3–6 h as needed (up to 5 or 8 doses in 24 h), provide continued relief from sore throat pain and soreness;22,29–31,34,36–38 six for flurbiprofen lozenges, one for spray, and one for microgranules. Several of the papers evaluated pain relief during the first 24 h of treatment, when throat symptoms are most prominent and often require repeated treatment.29,30,36,37 All of these papers reported significant reductions in sore throat pain (up to 80% greater compared to placebo; measured on the STPIS) over this treatment period.29,30,36,37 Five papers explored the efficacy of repeated self-dosing of flurbiprofen beyond the first 24 h. Schachtel et al36 observed that multiple-dose flurbiprofen lozenge over days 2–7 continued to provide significant reductions in sore throat pain intensity from before to 2 h after each dose, and that flurbiprofen provided 74% greater reduction in sore throat pain intensity vs placebo over days 2–7 (p<0.01). Likewise, de Looze et al34 reported that multiple-dose flurbiprofen spray provided a greater reduction in severity of throat soreness and pain intensity, and significantly greater sore throat relief compared with placebo, up to the end of the 3-day study period (p<0.05).

Blagden et al31 demonstrated the superiority of flurbiprofen vs placebo in relieving sore throat over days 1–4 overall (TOTPAR at the end of days 1–4; p=0.0113). However, in a subgroup of patients not prescribed concomitant antibiotics in this study, significance was reached on days 2 and 3 (p<0.05), but not on day 1 (p=0.06) and day 4 (p=0.09). In terms of change from baseline in sore throat relief, significance was achieved with multiple-dose flurbiprofen microgranules vs placebo at the end of day 1 (p=0.026), but not at the end of day 2 (p=0.101) and day 3 (p=0.078).38

In a study by Aspley et al,29 the efficacy of flurbiprofen lozenge was evaluated in a subgroup of patients with relatively severe sore throat pain (baseline STPIS score of >80.5 mm). In these patients, multiple-dose flurbiprofen provided 135.7% greater (269.9 mm*h; 95% CI: 84.7, 455.1) reduction in pain intensity than placebo-treated patients (p<0.01) over 24 h. Improvement of sore throat pain after single-dose flurbiprofen was similar for patients with relatively severe symptoms and the overall study population, with onset differentiated between flurbiprofen and placebo beginning at approximately 30–40 min through to 3 h (p<0.05). Moreover, Schachtel et al35 reported that pain reduction was achieved by 95% of flurbiprofen-treated patients over 3 h (vs 63% of placebo-treated patients; p=0.02) in a subgroup of patients (42%) with more severe sore throat pain at baseline (STS score >7 and Tonsillo-Pharyngitis Assessment [TPA] score >7).

Determining a reduction in pain that is clinically important, or meaningful to patients, may offer more interpretable results with direct clinical implications.44 Several of the studies included in this review have assessed “meaningful” pain relief with flurbiprofen.17,18,33,35 Using a double stopwatch (DSW) method (Table 2), Schachtel et al35 investigated both “first perceived” pain relief (the moment the patient experiences any pain relief, measured on the STPIS) and “meaningful” pain relief (when the patient experiences relief that is meaningful to them) with flurbiprofen lozenge. Results showed that 97% of flurbiprofen-treated patients (n=101) experienced “first perceived” pain relief, with 78% achieving “meaningful” analgesia within the 3 h study period. In contrast, although 76% of patients taking placebo lozenge (n=21) reported “first perceived” pain relief over the 3 h study period, the relief was not considered “meaningful” in over half of patients (52%). “Meaningful” pain relief was achieved by 32% (32/101) of flurbiprofen-treated patients within 30 min and by 66% (67/101) within 60 min – compared with 19% (4/21) and 43% (9/21) of placebo-treated patients, respectively. A subgroup analysis also demonstrated significant efficacy of flurbiprofen in patients with more severe sore throat; in these patients, “meaningful” relief was reported by 70% of flurbiprofen-treated patients and 13% of placebo-treated patients (p<0.01).

Meaningful pain relief was also assessed by Schachtel et al17 in another study using the established criteria of “at least moderate relief” of acute pain to define a clinically important effect size. Sore throat pain was assessed at frequent (2 min) intervals on the STPIS, and onset of pharmacological activity was defined as the median time of “first perceived” pain reduction if a patient reported clinically meaningful “at least moderate” relief. Patients receiving a single flurbiprofen lozenge first reported “meaningful” pain relief at 12 min, with a significant differentiation from placebo in terms of percentage reduction in pain intensity (indicative of change relative to each individual patient’s pretreatment pain intensity) beginning at 26 min (24% pain reduction with flurbiprofen vs 16% with placebo; p<0.05).

The previous findings were confirmed with flurbiprofen spray in a study by de Looze et al.33 Patients were required to report at least 30 min of “at least moderate” sore throat relief on the STRRS for the relief to be regarded as “clinically meaningful”. Significantly more patients using flurbiprofen spray reported at least 30 min of “at least moderate” relief than those using placebo during the 6 h after a single dose (55% vs 35%, respectively; OR: 2.31; 95% CI: 1.61, 3.62; p<0.0001), and this was achieved more quickly with flurbiprofen than placebo (HR: 1.96; 95% CI: 1.50, 2.57; p<0.0001); 150 min for flurbiprofen and not calculated for placebo due to less than 50% response. Sore throat severity was reduced by at least 2.2 mm on the STS from 75 min to 6 h post dosing, indicating “meaningful relief”.

Difficulty Swallowing

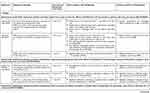

Eleven of the papers reviewed reported data evaluating the efficacy of flurbiprofen in reducing difficulty swallowing (Table 4) – a common symptom associated with inflammation of the throat, usually measured on the Difficulty Swallowing Scale (DSS; Table 2). Significantly greater improvements in swallowing have been observed from 5 min after taking single-dose flurbiprofen compared with placebo,34 and for up to 6 h post-dose.34 The superior efficacy of flurbiprofen in reducing difficulty swallowing has also been demonstrated with repeated dosing. Aspley et al29 observed a 99.6% greater reduction in difficulty swallowing with multiple-dose flurbiprofen lozenges compared with placebo over 24 h (p<0.01), and an even greater reduction (105.4%) in patients who had relatively severe difficulty swallowing (baseline DSS score >77.5 mm). Furthermore, significantly greater improvements in swallowing have been reported for longer treatment periods of up to 7 days compared with placebo.29–31,34,36–38

|  |  |

Table 4 Summary of Studies Reporting Difficulty Swallowing Outcomesa |

Sensation of Swollen Throat

Eleven of the papers reported data evaluating the efficacy of flurbiprofen in reducing the sensation of swollen throat (Table 5), commonly assessed on the Swollen Throat Scale (SwoTS; Table 2). As with the other symptoms associated with sore throat, the data generally support that flurbiprofen is effective at reducing the sensation of swollen throat rapidly after a single dose – with significantly greater reductions observed from 30 min to up to 6 h post-dose17,25,30,32,34,37 – and after multiple dosing over 1–7 days.22,29,30,34,36,37 Notably, Aspley et al29 observed a 69.3% greater reduction in sensation of swollen throat with multiple-dose flurbiprofen lozenges compared with placebo over 24 h (p<0.05), and an even greater reduction (148.6%) in patients who had relatively severe symptoms (baseline SwoTS score >81.5 mm). Only one study reported no difference between single-dose flurbiprofen and placebo in reduction of sensation of swollen throat over 2 and 6 h, but did report significant reductions in the symptom on days 3 (p=0.005) and 4 (p=0.001) of multiple dosing.22

|  |  |  |

Table 5 Summary of Studies Reporting Sensation of Swollen Throat Outcomesa |

Onset of Action

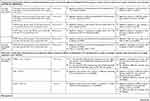

Several studies indicated that locally administered flurbiprofen can provide symptomatic relief from sore throat and associated symptoms from 1–30 min after taking a single dose, depending on the first assessment time point (Table 6).17,22,25,29,32–35,38 Burova et al25 reported that at least 90% of patients using single-dose flurbiprofen 8.75 mg spray or lozenge experienced at least “slight” sore throat relief (on the STRRS) from 1 min post completion of dose, with 55–59% of patients reporting “at least moderate relief” – an established measure of clinically meaningful effect – from 1 min. Similarly, Russo et al38 reported a significantly greater reduction in mean throat soreness with flurbiprofen 8.75 mg microgranules (p<0.001) and a significantly greater improvement in sore throat relief (p<0.0006) compared with placebo at 1 min post-dose.

|  |  |  |

Table 6 Summary of Studies Reporting Onset and Duration of Action of Single-dose Flurbiprofena |

Studies have also demonstrated early onset of relief from difficulty swallowing and sensation of swollen throat.29,32,34,38 A significantly greater reduction in difficulty swallowing with flurbiprofen compared with placebo was reported at 5 min post-dose by de Looze et al34 and Russo et al38 in patients using spray or microgranule formulations of flurbiprofen, and at 10 min post-dose (the first assessment time point) with lozenges (all p<0.05).29 A significantly greater reduction in sensation of swollen throat was also achieved at 30 min post-dose vs placebo with lozenges (p<0.05)32 and with flurbiprofen spray (p<0.001).34

Onset of analgesia attributable to the active ingredient of a lozenge is complicated by the inherent demulcent effect of the sugary vehicle base of the lozenge itself, which provides an immediate, but short-lived, soothing effect as a result of increasing salivation and lubrication of the mucosa.24,44 Assessments at 2-min intervals during the early stages of studies have demonstrated this effect.17,29 Several of the reviewed studies specifically assessed the onset of clinically relevant, or “meaningful”, analgesia with flurbiprofen in order to distinguish the analgesic effect of flurbiprofen from the demulcent effect of the lozenge base.17,33,35,38 As mentioned previously in the “Meaningful Pain Relief” section, median onset of pharmacological activity (“time to the first perceived reduction of sore throat pain” confirmed by “at least moderate pain relief”) was 12 min in patients taking flurbiprofen lozenge, compared with over 120 min (last assessment time) for the placebo group (p<0.001) in the study by Schachtel et al.17 In another paper from Schachtel et al,35 using the previously described DSW method, median time to “first perceived pain relief” for flurbiprofen-treated patients was 11 min (95% CI: 7.6, 14.3 min) compared with 19 min (95% CI: 4.8, 30.3 min) for placebo-treated patients (p=0.03). However, median time to “meaningful pain relief” was 43 min (95% CI: 36.4, 49.4 min) with flurbiprofen, (significantly different from placebo-treated patients; p=0.01). A subgroup analysis in patients with more severe sore throat reported a median time to “meaningful” relief of 47 min (95% CI: 35.4, 78.1 min) and a median time to “first perceived” relief of 16 min (95% CI: 7.3, 25.2 min) with flurbiprofen, both of which were significantly different from placebo (p=0.01 and p=0.04, respectively).

In the paper by Russo et al,38 in which onset of sore throat relief was evident at 1 min post-dose, the degree of change in throat soreness classified as “clinically important” (a reduction of 1–2 points on the 11-point ordinal TSS) was achieved with flurbiprofen microgranules at 30 min post-dose. de Looze et al33 reported significantly greater sore throat relief with flurbiprofen spray from 20 min (first assessment time point) post-dose (p<0.0001), with “meaningful” relief (sore throat severity reduced by at least 2.2 mm on the TSS) achieved at 75 min post-dose.

Duration of Action

Data from several studies suggest that single-dose flurbiprofen can provide long-lasting symptomatic relief of sore throat and associated symptoms over several hours (Table 6).17,22,25,29,30,32–34,37,38 de Looze et al34 reported significantly greater reductions in throat soreness (p<0.01), pain intensity (p<0.01), difficulty swallowing (p<0.05) and sensation of swollen throat (p<0.001), and significantly greater improvements in sore throat relief (p<0.001) with flurbiprofen spray vs placebo for up to 6 h post-dose. Similarly, Russo et al38 demonstrated significantly greater (and clinically relevant) improvements in sore throat relief and significantly greater reductions in difficulty swallowing (p<0.05 for both) with flurbiprofen microgranules vs placebo for up to 6 h post-dose (the last assessment time point). Studies investigating flurbiprofen lozenges have reported significantly greater reductions in throat soreness, pain intensity, difficulty swallowing and sensation of swollen throat, and significantly improved sore throat relief vs placebo for at least 2–4 h, dependent on the study assessment period.17,22,29,30,32,35,37

Other Symptoms Associated with Sore Throat

Patients with pharyngitis commonly report a number of symptoms beyond just “sore throat” when they seek professional intervention, and these symptoms may be described using a wide variety of sensory, emotional, and functional terms.28 Two papers25,28 have assessed the ability of flurbiprofen to provide relief from 10 features of sore throat commonly reported by patients using the recently developed and validated QuaSTI (Table 2).

Schachtel et al28 demonstrated a significant improvement (ie reduction in mean overall QuaSTI score) from baseline to 3 h post-dose with single-dose flurbiprofen lozenge (mean ±SD, −19.3 ± 18.62; p<0.001). This improvement was significantly greater with flurbiprofen compared with placebo lozenge (154%; p<0.05). With regards to the individual qualities of sore throat, patients using flurbiprofen lozenge consistently reported significant reductions of scores from baseline at 1, 2, and 3 h (all p<0.01). In addition, the changes in QuaSTI were confirmed as “clinically significant” for some of the individual qualities, with differences from pretreatment levels of at least two points on the Likert scales for swollen throat, difficulty swallowing, agonizing and throat soreness.

Burova et al25 demonstrated a significant improvement from baseline to 2 h post-dose for the sum score of all items on the QuaSTI for both flurbiprofen spray (mean ±SD, −29.0 ± 16.07; 95%CI: −31.20, −26.90) and lozenge (−27.9 ± 16.31; 95%CI: −30.10, −25.80) (p<0.0001 from baseline for both). There was a reduction from baseline to 2 h of at least two points for all the individual symptoms of sore throat on the QuaSTI, signifying “clinically significant” changes.

Sore throat associated with acute URTI is often accompanied by other troublesome upper respiratory tract symptoms, for example cough, post-nasal drip, swollen or tender neck glands, tickly throat, achiness and lack of energy.25,28 These can be assessed using the URTI questionnaire (Table 2). Schachtel et al28 observed that significant numbers of patients treated with flurbiprofen lozenges, but not placebo, reported an absence of several URTI symptoms (achiness, pressure around the eyes, mouth breathing, lack of energy, tender neck glands, headache, loss of appetite, sinus pressure, coughing, chest tightness, or sinus pain) at 3 h post-dose compared to pretreatment (all p<0.05). In particular, among patients reporting cough at baseline, 46% (11/24 patients) reported no coughing at 3 h (p=0.01).

Burova et al25 also demonstrated a significant reduction in the number of patients experiencing URTI symptoms with both flurbiprofen spray and lozenges. At 2 h post-dose, the number of patients experiencing URTI symptoms that can be attributed to or associated with sore throat (coughing, post-nasal drip, swollen neck glands, tender neck glands, throat tickle, and throat clearing) decreased relative to baseline. These decreases were statistically significant for every symptom, except tender neck glands (lozenge only; p=0.0881) and throat tickle (both formulations; p=0.3113 for spray and p=0.2249 for lozenge). There was an 85% and 54% reduction in the number of patients with cough from baseline to 2 h with spray and lozenge, respectively.

Streptococcal versus Non-Streptococcal Pharyngitis

The effectiveness of flurbiprofen in patients with or without strep A/C sore throat has been assessed in several of the reviewed papers.26,28,35,37 In a paper by Shephard et al,37 subgroup data from two clinical trials were combined to evaluate the efficacy of flurbiprofen lozenges in patients with and without microbiologically proven strep A/C. Strep A/C was confirmed in 24% (96/401) of patients who had a throat culture test. Significant pain reduction (on the STPIS) with single-dose flurbiprofen compared with placebo was observed for up to 4 h (p<0.01) for the overall population and for patients without strep A/C, and for up to 3 h for patients with strep A/C (both p<0.05). There were no differences in treatment effects in the strep A/C group compared with the non-strep A/C group (p>0.2 for all time points assessed up to 6 h). Likewise, there were no significant differences in flurbiprofen single-dose treatment effects in the strep A/C group compared with the non-strep A/C group for either difficulty swallowing or swollen throat (p>0.05 for all time points assessed up to 6 h). With multiple-dose flurbiprofen, reductions in pain intensity, and improvements in difficulty swallowing and swollen throat, were also similar regardless of strep A/C status, although the improvements observed in the strep A/C group were not statistically different from placebo, possibly due to the small patient numbers or the natural improvement of throat symptoms over time.

In a study by Schachtel et al, strep A/C was detected in 34% (42/122) of patients, and efficacy of flurbiprofen lozenges in reducing sore throat symptoms (on the QuaSTI) was similar regardless of strep A/C status.28 In a further analysis of the data,35 among flurbiprofen-treated patients with strep A/C, 82% reported “meaningful” pain relief (on the STPIS) within 3 h compared with 78% in the non-strep group. Moreover, there was no significant difference in median time to “meaningful” relief for flurbiprofen-treated patients with or without strep A/C (41 min vs 43 min, respectively; p=0.39). All patients with strep A/C reported “first perceived pain relief” with flurbiprofen within the 3-h study period. Likewise, in a study from Radkova et al,26 although only 5.4% (22/411) of patients tested positive for strep A/C sore throat, subgroup analyses showed similar efficacy (change in pain intensity on the STPIS at 2 h) with flurbiprofen spray and lozenges regardless of strep A/C status.

In a study from Blagden et al,31 59% (135/230) of flurbiprofen lozenge-treated patients also took concomitant antibiotics, as did 58% (133/229) of placebo-treated patients. Antibiotic usage did not affect sore throat relief (reported as TOTPAR) over days 1–4 within the flurbiprofen treatment group.

In addition to assessing the efficacy of flurbiprofen in managing the symptoms of sore throat, several of the studies also evaluated patients’ opinions of the overall success of the treatment, most using the Global Evaluation Scale (GLOBAL), the Satisfaction Scale (SATIS) and/or an overall treatment rating scale (Table 2).22,25,26,30–32,34,36,38

Significantly more patients taking flurbiprofen rated their treatment as “good”, “very good” or “excellent” on the GLOBAL compared with placebo after single- and multiple-dose treatment.34,36 Similarly, there was greater patient satisfaction on the SATIS after treatment, with a significantly higher proportion of patients reporting that they were “satisfied”, “very satisfied” or “extremely satisfied” with flurbiprofen compared with placebo.30,36 There were no significant differences between flurbiprofen spray and lozenges in terms of GLOBAL25 or SATIS.26 Flurbiprofen was also associated with benefit over placebo in studies using an overall treatment rating scale,22,31,32 and in a paper from Russo et al38 patients reported feeling significantly less distracted, less frustrated, and happier after taking flurbiprofen microgranules for 3 days compared with placebo (p<0.05).

Post-Operative Sore Throat (POST)

Two clinical studies investigating the effectiveness of flurbiprofen for the prevention of POST were eligible for inclusion in the review (Table 1).40,41 Uztüre et al41 evaluated the efficacy of flurbiprofen lozenges for preventing POST, hoarseness and dysphagia symptoms in patients in whom a ProSeal laryngeal mask airway (LMA) was inserted during general anesthesia. A single flurbiprofen lozenge, given 45 min before induction of anesthesia, effectively reduced the severity of early POST (30 min postoperatively) and dysphagia compared with placebo (p<0.05 for both). Likewise, dysphagia was significantly lower in the flurbiprofen group compared with placebo at 4 h and hoarseness at 12 h postoperatively (p<0.05 for both). The incidence of POST symptoms was not significantly different between the flurbiprofen and placebo groups throughout the duration of the study.

In the second study, Aydin et al40 compared flurbiprofen lozenges with a sea salt and glycerine spray, a gargle used for the prevention of symptoms associated with stomatitis and gingivitis, and no treatment (control group) for the prevention of POST in 320 patients (n=80 for each treatment group) undergoing elective genitourinary surgery under general anesthesia. Treatment was again given 45 min prior to induction of anesthesia. There was a significantly lower incidence of POST in the flurbiprofen lozenge and Siccoral® (Assos Pharmaceuticals, Istanbul, Turkey) spray groups at 0 and 1 h compared with those not treated (p<0.01 for all). There was a significantly lower incidence of POST in the Siccoral® spray group compared with the flurbiprofen group at 0 h post-extubation (p=0.002), but the incidence of POST was similar between all groups at 6 and 24 h post-extubation (p=0.141 and p=0.426, respectively).

Although not eligible for full inclusion in this review due to the use of a lower dose of flurbiprofen (0.325 mg per spray; two sprays to each tonsillar fossa) the efficacy of flurbiprofen spray (three times a day for 7 days), has also been demonstrated for the management of post-tonsillectomy pain.43 The severity of throat pain was lower in the flurbiprofen group (n=45) when compared with the placebo group (n=39), and this difference was statistically significant for all assessment days. Moreover, the flurbiprofen group required significantly less rescue analgesic than the placebo group during the study period on days 1, 3, 5, and 7.

Safety

Safety data from the reviewed studies are summarized in Table 7. Overall, flurbiprofen 8.75 mg was well tolerated, regardless of formulation; in the majority of studies the incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) was similar between the flurbiprofen and placebo treatment groups.17,28–30,33–38 The incidence of AEs was also similar between flurbiprofen and placebo in patients who were positive for strep A/C.37 In three papers the incidence of TEAEs was significantly higher with flurbiprofen vs placebo;22,31,32 taste perversion was the most commonly reported TEAE in these studies. Reports of taste perversion varied in their description by the patient; peppery taste, transient stinging or burning sensation, and unpleasant, bad or sour taste.22,31,32 No relationship between taste perversion and changes to the oral mucosa was demonstrated on oral examination,22,31,32 with the effect lasting only until dissolution of the lozenge was complete.22 When taste perversion was removed from the analyses there was no significant difference in incidence of AEs between treatment groups.22,32

|

Table 7 Summary of Flurbiprofen Adverse Eventsa |

Most AEs thought to be “definitely”, “probably” or “possibly” related to treatment were mild and transient, with no serious AEs reported for any of the formulations of flurbiprofen 8.75 mg. In addition to taste perversion, treatment-related AEs were most commonly associated with the digestive system (nausea, dyspepsia, diarrhea, abdominal pain/discomfort) or the nervous system (dry mouth, paresthesia, throat irritation). Discontinuations due to AEs were rare and generally resulted from AEs subsequently not considered to be of clinical relevance31 or thought to be related to underlying medical conditions.36 Radkova et al26 observed no significant differences in the incidence of TEAEs between the lozenge and the spray formulations.

Summary

Low dose (8.75 mg), locally administered flurbiprofen has been shown in the reviewed studies to provide effective relief of acute sore throat, including relief of throat pain and soreness, difficulty swallowing, sensation of swollen throat, and many other commonly reported qualities of sore throat.17,22,25,26,28–38 This efficacy has been demonstrated across all the different locally administered formulations studied (lozenge, spray or microgranules), providing patients and HCPs with the option to select the most appropriate formulation for the individual without compromising on efficacy. Moreover, data have demonstrated that flurbiprofen is effective even in patients with more severe or painful symptoms,29,35 who are more likely to visit their doctor and more likely to take antibiotics.4 Although these patients with more severe symptoms might be expected to be more resilient to the pharmacological effects of low dose (8.75 mg) flurbiprofen, studies demonstrated that the beneficial effects were actually similar or more pronounced in these patients compared with the overall study population.29,35

The reviewed studies confirm the fast onset of symptomatic relief with flurbiprofen, beginning as early as 1–2 min post-dose.17,25,38 The demulcent activity of lozenges provides a rapid soothing effect (“active placebo”) as soon as they are sucked and allows a high initial deposition of active ingredient in the mouth and throat. The spray formulation delivers a full dose immediately at the site of pain and inflammation, coating the posterior pharynx.24 This early onset of relief was most apparent in studies that employed a short time interval between assessments (eg 2 min), and initial assessment within 1–2 min after flurbiprofen administration.17,25,38 The data reviewed also demonstrate that “clinically meaningful” relief attributable to the anti-inflammatory effects of flurbiprofen occurs rapidly (from around 12 min post-dose)17 and is sustained for up to 4–6 h (the last time point assessed after a single dose).17,30,32–34,37,38

Sore throat lasts for around 3–7 days,11 therefore, many patients will require repeated dosing to relieve ongoing symptoms. Seven of the nine studies included in this review reported data for single- and multiple-dose flurbiprofen, suggesting that flurbiprofen administered 3–6 hourly when required, up to five times a day for up to 7 days, continues to provide clinically relevant, long-lasting relief for those patients whose symptoms remain bothersome.29–31,34,36–38 Patients entering these studies may have had a sore throat that started up to 7 days previously; therefore, the “first 24-h” period may actually have been up to the seventh day of these patients’ symptoms. As acute sore throat is of limited duration, with over 80% improving within a week,10 this may explain why the differences between flurbiprofen and placebo over subsequent days did not reach statistical significance in all of the studies.30,31,38

Despite the fact that antibiotics are ineffective against viruses,11,14 and therefore inappropriate for up to 80% of pharyngitis cases,10 antibiotic prescribing for this condition remains commonplace in primary care.5 Current treatment guidelines advocate symptomatic relief of sore throat as first-line treatment; even in bacterial sore throat, antibiotics do not provide immediate or useful relief of symptoms, with half of patients still experiencing pain after 3 days.11 Moreover, physicians face considerable challenges in the accurate diagnosis of bacterial sore throat, with misdiagnosis potentially leading to inappropriate antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance.5,37 Shephard et al highlighted the unreliability of strep A diagnosis based on clinical findings, with an 86.9% false positive result for strep A based on diagnosis by clinical features alone.37 Even using a rapid strep test, the study suggested that 23.9% of patients would have received antibiotics unnecessarily.37 Given its proven efficacy at providing fast and long-lasting relief from sore throat, particularly in the first few days when symptoms are worst,12,13 flurbiprofen offers a useful first-line treatment option for symptomatic relief in patients with “uncomplicated” acute sore throat, thus helping to reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescribing. Studies confirm the efficacy of flurbiprofen in patients both with and without strep sore throat,26,28,35,37 although the analyses included in this review are limited by the relatively low incidence of strep A/C positive patients. As most strep sore throats will resolve naturally over time, flurbiprofen can be considered prior to a definitive diagnosis of strep A/C; with the single-dose effects lasting for 3–4 h in these patients, it is reassuring that more persistent, severe or worsening symptoms associated with strep throat are unlikely to be “masked”, allowing patients to seek further advice and potentially antibiotics if required.37 Even when the symptoms and course of sore throat suggest that antibiotics may be warranted, flurbiprofen can be safely combined with antibiotic therapy to effectively relieve pain and other symptoms that antibiotics will not immediately alleviate.31

NSAIDs have been associated with gastrointestinal AEs, which have been shown to be dose related.19 However, use of the lowest single dose of flurbiprofen proven to be effective for the relief of sore throat (8.75 mg)22,27 means that flurbiprofen was well-tolerated across the reviewed studies, with a predominantly mild and transient AE profile similar to placebo in the majority of studies.17,28–30,33–38 Taste perversion was more common with flurbiprofen lozenge than placebo in three studies; the high incidence of this AE can be attributed to the outdated Coding Symbols for a Thesaurus of Adverse Reaction Terms (COSTART) terminology used to classify the event in these older studies.22,31,32 Taste perversion is considered to be related to patient acceptability rather than tolerability and lasts only until dissolution of the lozenge is complete.22,31,32 However, as the reviewed studies observed that patients’ ratings of satisfaction and overall treatment efficacy were significantly better with flurbiprofen treatment than with placebo, patient acceptability does not appear to be an issue.22,25,26,30–32,34,36,38

The results of the two POST studies included in this review are consistent with the findings of previous studies confirming the efficacy of a preoperative, locally delivered NSAID for the prevention of POST.45 A systematic review of clinical studies in adults undergoing elective surgery under general anesthesia found that the topical NSAID benzydamine significantly decreased the incidence of POST compared with nonanalgesic controls; however, POST severity was not significantly reduced in this comparison.45 Benzydamine was also associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of POST when compared with lidocaine.45

In conclusion, the studies included in this review confirm that single- and multiple-dose flurbiprofen 8.75 mg, locally administered in lozenge, spray or microgranule form, is a well-tolerated and effective first-line treatment option for the fast and long-lasting symptomatic relief of sore throat, including in patients with more severe symptoms, patients with confirmed strep A/C sore throat, and patients taking concomitant antibiotics. In addition, a single preoperative dose of flurbiprofen lozenge appears to be effective for preventing or reducing the severity of early POST in patients undergoing general anesthesia.

|

Figure 1 Publication assessment process. |

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance was provided by Sarah Johnson at Elements Communications Ltd, Westerham, UK and funded by Reckitt Benckiser. The authors are grateful to Melissa Saint Hill for collating data and contributing to the earlier drafts of the manuscript. Melissa Saint Hill was employed by Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare Ltd, UK during the first draft of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting and revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

Ferdinandus de Looze has been an investigator on two studies sponsored by Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare Ltd, UK. Adrian Shephard and Adam Smith are employees of Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare Ltd, UK. Adrian Shephard reports a patent 20150231063 pending. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Finley CR, Chan DS, Garrison S, et al. What are the most common conditions in primary care? Systematic review. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(11):832–840.

2. Addey D, Shephard A. Incidence, causes, severity and treatment of throat discomfort: a four-region online questionnaire survey. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2012;12:9. doi:10.1186/1472-6815-12-9

3. van Driel ML, De Sutter A, Deveugele M, et al. Are sore throat patients who hope for antibiotics actually asking for pain relief? Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(6):494–499. doi:10.1370/afm.609

4. Shephard A. A questionnaire-based study in 12 countries to investigate the drivers of antibiotic-seeking behavior for sore throat. J Fam Med Community Health. 2014;1(3):1014.

5. Dallas A, van Driel M, Morgan S, et al. Antibiotic prescribing for sore throat: a cross-sectional analysis of the ReCEnT study exploring the habits of early-career doctors in family practice. Fam Pract. 2016;33(3):302–308. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmw014

6. Wessels MR. Clinical practice. Streptococcal pharyngitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(7):648–655. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1009126

7. Worrall G. Acute sore throat. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(7):791–794.

8. Worrall GJ. Acute sore throat. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(11):1961–1962.

9. Bisno AL. Acute pharyngitis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(3):205–211. doi:10.1056/NEJM200101183440308

10. Ebell MH, Smith MA, Barry HC, Ives K, Carey M. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have strep throat? JAMA. 2000;284(22):2912–2918. doi:10.1001/jama.284.22.2912

11. Spinks A, Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(11):CD000023.

12. Eccles R. Mechanisms of symptoms of the common cold and influenza. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2007;68(2):71–75. doi:10.12968/hmed.2007.68.2.22824

13. Witek TJ, Ramsey DL, Carr AN, Riker DK. The natural history of community-acquired common colds symptoms assessed over 4-years. Rhinology. 2015;53(1):81–88. doi:10.4193/Rhin14.149

14. Kenealy T. Sore throat. BMJ Clin Evid. 2014;3:1509.

15. Pelucchi C, Grigoryan L, Galeone C, et al. Guideline for the management of acute sore throat. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(Suppl 1):1–28. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03766.x

16. National Institute for Heath and Care Excellence (NICE). Sore throat (acute): antimicrobial prescribing. NICE guideline NG84. January 2018.

17. Schachtel B, Aspley S, Shephard A, et al. Onset of action of a lozenge containing flurbiprofen 8.75 mg: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with a new method for measuring onset of analgesic activity. Pain. 2014;155(2):422–428. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2013.11.001

18. Schachtel B, Shephard A, Sanner K, et al. Long-lasting relief of throat symptoms (throat pain and swollen throat) and throat function (ability to swallow) with flurbiprofen 8.75 mg lozenge. Pain Pract. 2016;16:169.

19. Matthews ML. The role of dose reduction with NSAID use. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(14 Suppl):s273–277.

20. Limb M, Connor A, Pickford M, et al. Scintigraphy can be used to compare delivery of sore throat formulations. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(4):606–612. doi:10.1111/ijcp.2009.63.issue-4

21. Gonzalez-Younes I, Wagner JG, Gaines DA, Ferry JJ, Hageman JM. Absorption of flurbiprofen through human buccal mucosa. J Pharm Sci. 1991;80(9):820–823. doi:10.1002/jps.2600800903

22. Watson N, Nimmo WS, Christian J, Charlesworth A, Speight J, Miller K. Relief of sore throat with the anti-inflammatory throat lozenge flurbiprofen 8.75 mg: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of efficacy and safety. Int J Clin Pract. 2000;54(8):490–496.

23. Imberti R, De Gregori S, Lisi L, Navarra P. Influence of the oral dissolution time on the absorption rate of locally administered solid formulations for oromucosal use: the flurbiprofen lozenges paradigm. Pharmacology. 2014;94(3–4):143–147. doi:10.1159/000367663

24. Farrer F. Sprays and lozenges for sore throats. S Afr Pharm J. 2013;80(5):8–11.

25. Burova N, Bychkova V, Shephard A. Improvements in throat function and qualities of sore throat from locally applied flurbiprofen 8.75 mg in spray or lozenge format: findings from a randomized trial of patients with upper respiratory tract infection in the Russian Federation. J Pain Res. 2018;11:1045–1055. doi:10.2147/JPR

26. Radkova E, Burova N, Bychkova V, DeVito R. Efficacy of flurbiprofen 8.75 mg delivered as a spray or lozenge in patients with sore throat due to upper respiratory tract infection: a randomized, non-inferiority trial in the Russian Federation. J Pain Res. 2017;10:1591–1600. doi:10.2147/JPR

27. Schachtel BP, Homan HD, Gibb IA, Christian J. Demonstration of dose response of flurbiprofen lozenges with the sore throat pain model. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;71(5):375–380. doi:10.1067/mcp.2002.124079

28. Schachtel B, Shephard A, Schachtel E, Lorton MB, Shea T, Aspley S. Qualities of Sore Throat Index (QuaSTI): measuring descriptors of sore throat in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pain Manag. 2018;8(2):85–94. doi:10.2217/pmt-2017-0041

29. Aspley S, Shephard A, Schachtel E, Sanner K, Savino L, Schachtel B. Efficacy of flurbiprofen 8.75 mg lozenge in patients with a swollen and inflamed sore throat. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(9):1529–1538. doi:10.1080/03007995.2016.1187119

30. Schachtel B, Aspley S, Shephard A, Shea T, Smith G, Schachtel E. Utility of the sore throat pain model in a multiple-dose assessment of the acute analgesic flurbiprofen: a randomized controlled study. Trials. 2014;15:263. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-15-263

31. Blagden M, Christian J, Miller K, Charlesworth A. Multidose flurbiprofen 8.75 mg lozenges in the treatment of sore throat: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in UK general practice centres. Int J Clin Pract. 2002;56(2):95–100.

32. Benrimoj SI, Langford JH, Christian J, Charlesworth A, Steans A. Efficacy and tolerability of the anti-inflammatory throat lozenge flurbiprofen 8.75mg in the treatment of sore throat: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Drug Investig. 2001;21(3):183–193. doi:10.2165/00044011-200121030-00004

33. de Looze F, Russo M, Bloch M, Montgomery B, Shephard A, DeVito R. Meaningful relief with flurbiprofen 8.75 mg spray in patients with sore throat due to upper respiratory tract infection. Pain Manag. 2018;8(2):79–83. doi:10.2217/pmt-2017-0100

34. de Looze F, Russo M, Bloch M, et al. Efficacy of flurbiprofen 8.75 mg spray in patients with sore throat due to an upper respiratory tract infection: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Gen Pract. 2016;22(2):111–118. doi:10.3109/13814788.2016.1145650

35. Schachtel B, Aspley S, Shephard A, Schachtel E, Lorton MB, Shea T. Onset of analgesia by a topically administered flurbiprofen lozenge: a randomised controlled trial using the double stopwatch method. Br J Pain. 2018;12(4):208–216. doi:10.1177/2049463718756152

36. Schachtel BP, Shephard A, Shea T, et al. Flurbiprofen 8.75 mg lozenges for treating sore throat symptoms: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Pain Manag. 2016;6(6):519–529. doi:10.2217/pmt-2015-0001

37. Shephard A, Smith G, Aspley S, Schachtel BP. Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies on flurbiprofen 8.75 mg lozenges in patients with/without group A or C streptococcal throat infection, with an assessment of clinicians’ prediction of ‘strep throat’. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(1):59–71. doi:10.1111/ijcp.12536

38. Russo M, Bloch M, de Looze F, Morris C, Shephard A. Flurbiprofen microgranules for relief of sore throat: a randomised, double-blind trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(607):e149–155. doi:10.3399/bjgp13X663118

39. Muderris T, Tezcan G, Sancak M, Gul F, Ugur G. Oral flurbiprofen spray for postoperative sore throat and hoarseness: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Minerva Anestesiol. 2019;85(1):21–27. doi:10.23736/S0375-9393.18.12703-9

40. Aydın GB, Ergil J, Polat R, Sayın M, Akelma FK. Comparison of Siccoral® spray, Stomatovis® gargle, and Strefen® lozenges on postoperative sore throat. J Anesth. 2014;28(4):494–498. doi:10.1007/s00540-013-1749-7

41. Uztüre N, Menda F, Bilgen S, Keskin Ö, Temur S, Köner Ö. The effect of flurbiprofen on postoperative sore throat and hoarseness After LMA-ProSeal insertion: a randomised, clinical trial. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim. 2014;42(3):123–127. doi:10.5152/TJAR.2014.35693

42. El-Boghdadly K, Bailey CR, Wiles MD. Postoperative sore throat: a systematic review. Anaesthesia. 2016;71(6):706–717. doi:10.1111/anae.2016.71.issue-6

43. Muderris T, Gul F, Yalciner G, Babademez MA, Bercin S, Kiris M. Oral flurbiprofen spray for posttonsillectomy pain. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;155(1):166–172. doi:10.1177/0194599816637865

44. Farrar JT, Portenoy RK, Berlin JA, Kinman JL, Strom BL. Defining the clinically important difference in pain outcome measures. Pain. 2000;88(3):287–294. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00339-0

45. Kuriyama A, Aga M, Maeda H. Topical benzydamine hydrochloride for prevention of postoperative sore throat in adults undergoing tracheal intubation for elective surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaesthesia. 2018;73(7):889–900. doi:10.1111/anae.14224

46. Schachtel BP, Fillingim JM, Beiter DJ, Lane AC, Schwartz LA. Rating scales for analgesics in sore throat. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984;36(2):151–156. doi:10.1038/clpt.1984.154

47. Schachtel BP, Fillingim JM, Thoden WR, Lane AC, Baybutt RI. Sore throat pain in the evaluation of mild analgesics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1988;44(6):704–711. doi:10.1038/clpt.1988.215

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2019 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.