Back to Journals » International Journal of General Medicine » Volume 16

Level of Depression and Anxiety on Quality of Life Among Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis

Authors Alshelleh S, Alhawari H, Alhouri A, Abu-Hussein B, Oweis A

Received 5 March 2023

Accepted for publication 26 April 2023

Published 10 May 2023 Volume 2023:16 Pages 1783—1795

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S406535

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Scott Fraser

Sameeha Alshelleh,1 Hussein Alhawari,1 Abdullah Alhouri,2 Bilal Abu-Hussein,3 Ashraf Oweis4

1Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, The University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan; 2Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading, UK; 3Department of Medicine, The University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan; 4Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Amman, Jordan

Correspondence: Abdullah Alhouri, Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Royal Berkshire Hospital, London Road, Reading, RG1 5AN, UK, Email [email protected]

Background: Despite the growing concern worldwide regarding the quality of life (QoL) and mental well-being among chronic kidney disease (CKD), a few research has been done to address this issue. The study aims to measure depression, anxiety, and QoL prevalence among Jordanian patients with End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) on hemodialysis and how all of these variables are correlated.

Methods: This is a cross-sectional, interview-based study on patients at the Jordan University Hospital (JUH) dialysis unit. Sociodemographic factors were collected, and the prevalence of depression, anxiety disorder, and QOL was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ9), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD7), and the WHOQOL-BREF, respectively.

Results: In a study of 66 patients, 92.4% had depression, and 83.3% had generalised anxiety disorder. Females had significantly higher depression scores than males (mean = 6.2 ± 3.77 vs 2.9 ± 2.8, p < 0.001), and single patients had significantly higher anxiety scores than married patients (mean = 6.1 ± 6 vs 2.9 ± 3.5, p = 0.03). Age was positively correlated with depression scores (rs= 0.269, p = 0.03), and QOL domains showed an indirect correlation with GAD7 and PHQ9 scores. Males had higher physical functioning scores than females (mean = 64.82 vs 58.87, p = 0.016), and patients who studied in universities had higher physical functioning scores than those with only school education (mean of College/University = 78.81 vs mean of School Education = 66.46, p = 0.046). Patients taking < 5 medications had higher scores in the environmental domain (p = 0.025).

Conclusion: The high prevalence of depression, GAD, and low QOL in ESRD patients on dialysis highlights the need for caregivers to provide psychological support and counselling for these patients and their families. This can promote psychological health and prevent the onset of psychological disorders.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, end stage kidney disease, hemodialysis, quality of life, depression, generalized anxiety disorder

A Letter to the Editor has been published for this article.

Background

End stage kidney disease (ESKD) is a condition in which the kidneys fail irreversibly, necessitating the use of renal replacement therapy like dialysis or kidney transplantation to maintain life.1 In Jordan, the prevalence of ESKD is estimated at 709 per million,2 with limited availability of transplants relative to the demand, resulting in most patients requiring dialysis.3

Despite the increasing global concern regarding the quality of life (QoL) and mental well-being of chronically ill patients, few studies have explored these issues and their associations in Jordan. Furthermore, research investigating the prevalence of depression and anxiety and their correlation with QoL among ESKD patients is limited, despite poor QoL being commonly expected in these individuals and associated with higher risks of hospitalization and mortality.4

Throughout the course of chronic kidney disease (CKD), patients encounter significant psychological challenges that affect their well-being, including coping with the life-threatening diagnosis and lifelong treatment, dialysis techniques, treatment side effects, and complications.5 As such, managing CKD/ESKD requires not only addressing the clinical aspects of the disease but also maintaining the patient’s QoL from diagnosis to end-of-life care.5

Studies report depression as the most common psychiatric abnormality among ESKD patients.6,7 The prevalence of interview-based depression is approximately 20% in the United States.7 A study conducted in Saudi Arabia to assess anxiety and depression among ESKD Saudi patients on hemodialysis revealed that 21.1% and 23.3% were probable cases of anxiety and depression, respectively.8

There is a growing emphasis on the mental health and quality of life of dialysis patients, with suggestions to consider it a significant predictor of mortality and morbidity. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines the quality of life as an individual’s perception of their position in life, considering their cultural context, values, goals, expectations, standards, and concerns. Quality of life is increasingly used to determine the well-being and prognosis of dialysis patients.9

This study aims to investigate the prevalence of depression and anxiety among dialysis patients at Jordan University Hospital (JUH) and examine their associations with QoL. Additionally, we explored the associations between sociodemographic characteristics, depression, anxiety, and QoL.

To our knowledge, this study is the initial investigation in Jordan to examine the correlation between depression, anxiety, and the quality of life (QoL) of dialysis patients. Identifying the indicators and predictors of anxiety and depression in these patients, and administering suitable cognitive and pharmaceutical treatments, can help promptly detect and manage these disorders, which may enhance the QoL of dialysis patients in Jordan.

Methods

This cross-sectional study, conducted between August 2019 and February 2020, assessed the levels of depression, anxiety, and quality of life in patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) undergoing dialysis at the dialysis unit in JUH. The study used a convenience sample of 66 patients, who were interviewed using a structured, pre-tested questionnaire that had been previously used in the literature. The questionnaire was designed as a Likert scale type and was translated into Arabic and back to English by a bilingual translator. Inclusion criteria for ESRD patients included being older than 18 years, receiving HD for at least six months, and understanding Arabic. Patients with any psychiatric illness or history of substance abuse were excluded from the study. Data was collected by interviewing patients, as some may not have been able to complete the questionnaire independently due to their health status.

The questionnaire consisted of three parts. The first part collected sociodemographic data, such as age, marital status, level of education, occupation, and a brief past medical and drug history. The second section of the questionnaire involved the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) to screen and evaluate the intensity of depression. Scores ranged from 0–3 and were classified as follows: minimal or no depression (0–4), mild depression (5–9), moderate depression (10–14), or severe depression (15–21).10 The third section of the questionnaire included the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) to assess the severity of anxiety, with scores ranging from 0–3. Scores were also classified into minimal or no anxiety (0–4), mild anxiety (5–9), moderate anxiety (10–14), or severe anxiety (15–21).11 The third and final part of the questionnaire was the WHOQOL-BREF, which included 26 questions to assess the quality of life. Responses ranged from “not always” to “to a great degree”.

The WHOQOL-BREF is a health-related questionnaire created by the WHOQOL group to measure the quality of life of individuals with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). It has 26 facets and assesses four dimensions of quality of life: physical health, psychological well-being, social relationships, and environmental factors. The questionnaire can be completed by the patient themselves or administered by an interviewer. After the study subjects completed the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire, the scores were calculated. The raw scores were converted to transformed scores ranging from 0 to 100. A higher score indicates a better quality of life.The collected data was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 24, with a significance level of p < 0.05. To ensure that the data met the assumptions for parametric statistics, normality was evaluated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, histograms, and Q-Q plots. Levene’s test was used to assess equal variances, after which parametric statistics were used. The effects of sociodemographic variables such as gender, smoking, marital status, education, and medication use on anxiety (GAD-7) and depression (PHQ-9) scores were evaluated using independent samples t-test. Spearman’s rank-order correlation was used to determine the association between age, duration of chronic kidney disease, anxiety and depression scores. The effects of sociodemographic variables on QOL-BREF scores were assessed using independent samples t-test, and the correlation between WHOQOL-BREF domain scores, QOL scores, PHQ-9, and GAD-7 scores was determined using Pearson’s correlation.

Results

The total sample of 66 patients consisted of 32 males (48.5%) and 34 females (51.5%), with a mean age of 54. The mean duration of ESKD is 10.4 years. Descriptive data of the patient’s laboratory values and Sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

|

Table 1 Sociodemographic Characteristics and Laboratory Parameters of the Participants |

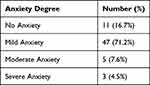

The patients were interviewed with the PHQ9 for depression and GAD7 for anxiety questionnaires. Description of questionnaires PHQ9 and GAD7 are shown in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Sixty-one patients (92.4%) were found to have depression, and 55 patients (83.3%) were found to have a generalized anxiety disorder, with variable degrees of depression (Table 4) and anxiety levels (Table 5).

|

Table 2 Description of Depression 9-Item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) |

|

Table 3 Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) Description |

|

Table 4 Depression Degree |

|

Table 5 Anxiety Degree |

Correlations between the demographic characteristics and PHQ9 scores are tabulated in Table 6. Females had a significantly higher depression score (mean = 6.2 ± 3.77) than males (mean = 2.9 ± 2.8), with a p-value <0.001. There was a positive correlation between age and depression score (rs= 0.269, p=0.03) (Table 7). There were no other significant differences between groups related to depression. Correlations between the demographic characteristics and GAD7 scores are tabulated in Table 8. Single patients had a significantly higher anxiety score (Mean=6.1 ± 6) than married patients (Mean=2.9 ± 3.5), p value=0.03. No other significant differences in groups related to anxiety scores.

|

Table 6 Comparison Between Depression and Sociodemographic Characteristics |

|

Table 7 Linear Correlation Between GAD7 Score, PHQ9 Score and the Score Mean of WHO-QOL BREF Domains, Age and Chronic Kidney Disease Duration (Years) for the Participant |

|

Table 8 Comparison Between Anxiety Score and Sociodemographic Characteristics |

Regarding the four domains of quality of life, the mean total QoL for each domain was as follows: Physical functioning (mean =71.74 ± 22.26), Psychological functioning (mean= 75.32 ± 17), Social functioning (mean=75.83 ± 18.53), Environmental domain (mean = 76.55 ± 13.72). There is also a direct correlation between them within each other. When a particular domain increases its score, there is a tendency that the other correlated domains will also increase, and vice-versa. There is a moderate tendency correlation between score means of the domain physical health (PH) with psychological (PS) (r= 0.329). A weak tendency correlation is shown between domain PH and environmental domain (ED) (r= 0.277), PS, and ED (r= 0.291) (Table 9). There is an indirect correlation between the quality of life domains with GAD7 and PHQ9 scores. There is a moderate tendency indirect correlation between the score means of Domain PS and GAD7 score (r= −0.519) and PHQ9 (r= −0.339), domain PS and GAD7 (r= −0.430) and PHQ9 (r= −0.367), SH and GAD7 (r= −0.34) and PHQ9 (r= −0.418) (Table 7).

|

Table 9 Linear Correlation Between the Score Mean of WHO-QOL BREF Domains |

Correlations between the demographic characteristics and QOL-BREF scores are tabulated in Table 10. Males had a higher physical functioning score than females (mean=79.09 for males, 64.82 for females), p=0.016. Smokers had a higher score in physical functioning than non-smokers (mean score for smokers= 81.11 higher than non-smokers, Mean=67.96) p-value = 0.037. There was no significant difference in marital status regarding the quality of life. Patients that studied in universities had a higher physical functioning score (mean of College/University = 78.81, mean of School Education = 66.46), p value= 0.046. Patients who used less than five medications had a better environmental domain score than those who used more than five medications. The mean score of patients taking less than five medications was 80.66, while the mean score of patients taking more than five medications was 71.87. This difference was statistically significant with a p-value of 0.025, as shown in Table 10.

|

Table 10 Comparison Between the Score Mean of WHO-QOL BREF Domains and Sociodemographic Characteristics |

Discussion

The psychological health of dialysis patients is getting more attention, along with their quality of life, with suggestions to make it an essential predictor of mortality and morbidity.

Depression is a primary global public health concern, as 3.8% of the population worldwide is living with depression, according to WHO. Moreover, a severe health condition can lead to poor work, school, or university functions. It is also known to lead to suicide and suicidal ideation.12 Depression is also common among chronic disease patients, such as diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or Chronic kidney diseases.13 Thus, it is essential to understand the condition, its nature, risk factors, and how it affects the QOL of chronic disease and screen patients who suffer from chronic diseases.

Anxiety disorder can also negatively impact various forms of daily activities and functions. People with a generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) are worried about many things related to daily routine and ordinary life events.14 A systematic review study that included the studies published between 1994 and 2009 concluded that patients with chronic diseases are more likely to be affected by anxiety.14

Similar to the previously conducted studies which investigated depression among patients who have a chronic disease that showed high prevalence, our result showed that depression is common among CKD and patients on dialysis. In a study conducted by Sameeha et al, the researchers investigated predialysis CKD patients and found the prevalence to be about 58%.15 It’s well established that depression is the most common psychiatric illness found among hemodialysis patients, in particular with a prevalence that varies between 20% at the lowest to 88.8% at the highest,2,7,16–28 while most of the studies have shown the depression prevalence to be around 50% or more.29 Anxiety is also a common psychiatric disorder among Hemodialysis patients, with a prevalence ranging from 23.6% at the lowest to 92.5% at the highest. However, it’s worth mentioning that the prevalence of anxiety was lower than depression in most studies that investigated both mental illnesses.17,18,22,24–28,30

Our study found a prevalence of 92.4% for depression and 83.3% for anxiety. Some studies in the literature reported similar findings.2,24 On the other hand, most studies have shown lower prevalence rates than that.7,16–18,20–23,25–30 We believe these relatively higher rates could be attributed to many factors, such as cultural differences, the effect of season on depression, and the interview setting in the dialysis unit, which may represent a stressful environment.

Regarding gender associations, we have found that female patients had a significantly higher depression score than male patients, a finding supported by other studies.17,18,20,23,31,32 To our knowledge, only one study showed higher male depression scores.25 Some studies failed to show any differences between males and females in that regard.26,33 These results align with the literature, which indicates that women are more susceptible to affective disorders than men.34

In addition, in our study, age had a moderate positive correlation with depression scores. Many studies have similar results.20,21,25,31,32,35,36 However, some studies showed no correlation between depression and patients’ age.26,37 Our findings might be attributed to the positive correlation between longer durations of dialysis and depression that have been found in many research studies.19,26 Several studies have also linked this relationship to the co-morbid conditions that are highly prevalent in older patients, which affect this age group’s functional ability and quality of life.31,38,39

Marital status impacts patients’ well-being as their partner provides support on many levels.40 It is an essential factor contributing to depression scores and QoL domains.38,41 In the literature, many studies found a significant correlation between depression, anxiety, and QOL from one side and marital status from the other side.17,19,42–46 Sameeha et al conducted a study in Jordan and found that married CKD patients had a significantly lower prevalence of depression.15 An interesting study of 3865 participants from 2005–2014 investigated the effect of marital status on depression among CKD patients and found a significant relationship between marital status and mortality among CKD patients.44 However, some studies have not found any association between marital status with anxiety, depression, or QOL.26,43,44,47,48

In our study, single patients had only significantly higher anxiety scores compared to married patients but no significant differences regarding depression and QoL. Additionally, patients married with children had a 54%-reduced risk of having a clinical case of anxiety compared to divorced/widowed (AOR = 0.46, 95% CI (0.21, 0.98). This is similar to two studies from Greece (Ginieri-Coccossis et al, 2008) and Jordan (Musa et al, 2018). The slight impact of relationships on Anxiety with no other effects on QOL or depression might be acquainted with the fact that Jordan is a densely family-oriented society and that other means of social support exist beyond spouses, which is consistent with a common finding in the literature, for example, a study conducted on Jordan found that having any form of social support will improve the QOL of CKD patients on dialysis. Another study used a correlational design, investigated the relationship between depression, QOL, and social support among hemodialysis patients concluded that social support would lower the risk of depression and impact the QOL of the patients positively.49,50

Some studies stated that low QoL scores significantly contribute to developing depressive symptoms, and those with no depression, anxiety, and stress had better QoL.29,31,39,51–53 This supports our findings of a negative correlation between QoL domains and GAD7 and PHQ9 scores, with lower depression and GAD scores correlating with higher QoL domains. Thus, screening CKD patients and hemodialysis patients for depression and anxiety are of paramount importance.

Quality of life was investigated in our study within the aspects of the four standard domains. Interestingly, compared to the average Jordanian population, the mean QoL scores of the patients on dialysis in each of the four domains were higher.54 The smaller sample size may explain this. However, satisfaction with the status of the patient’s standard of living may play an essential role in seeing life from a different and possibly lighter perspective.

These domains were also found to have a direct positive correlation with each other. This means that a high score in one domain would be correlated with high scores in the other domains. The physical domain showed a significant correlation with the psychological and the environmental domains, and the psychological domain showed a significant correlation with the environmental domain.

Consistent with our findings, a study that has used the WHO brief questionnaire has shown that the physical and psychological domains are most affected in dialysis patients.55 Another study that used the 36 – Item Short – Form Health Survey (SF-36) found the same results.39 According to WHO, the physical domain consists of questions related to pain, drug dependence, energy availability, mobility, sleep satisfaction, and ability to carry out daily activities. In contrast, the psychological domain consists of questions related to feelings, thinking, learning, memory and concentration, Self-esteem, Bodily image and appearance, and feelings. Hence, the physical limitations due to fatigue and weakness and the effects of fluid restriction and dietary modification on physical health are all factors that can explain the impairment of the physical domain among Hemodialysis patients. Pain, weakness, and dizziness are common complaints for hemodialysis patients, impacting the physical domain.56 On the other hand, we believe that the Psychological burden can be attributed to the changing of new stressful lifestyles that hemodialysis patients need to adapt to.

The Association between gender and QOL was investigated in the literature. A study by Rostami et al showed that males had better QOL than females, which contradicts other studies.57–59 In our study, male patients had better scores in all four domains. The differences between males’ and females’ scores in the physical domains were statistically significant; the same finding was observed by Sullivan et al.60

The literature has a well-established correlation between higher educational levels and QoL. Many studies showed a positive correlation between educational level and different domains of QOL.31,61–63 In our research, we have found a positive correlation between the physical domain and educational level. The higher ability can explain this to understand the disease. Therefore, higher rates of medication compliance and following a healthy lifestyle.

Our study showed that smokers had significantly higher physical functioning scores than non-smokers, with nonsignificant differences in the other domains. This is similar to a result of a study from Palestine, where they found smoking to be positively associated with QOL. One study has proposed a theory on the possible link between smoking and QoL, stating that smoking was used to avoid loneliness, improve mood, sleep better, and relieve pain.54

Smoking has been reviewed in the literature with conflicted findings, with some studies stating that most non-smoking patients had depression and others showing that more than half of patients who smoke on dialysis have depression.31 In Our study, we have not found Smoking to significantly affect the prevalence of depression or GAD.

Polypharmacy is defined as receiving more than 5 medications, which is not uncommon in CKD patients on hemodialysis.64 Thus, linking the number of medications to patients’ QoL scores is reasonable. A study in the literature linked taking higher numbers of medications (>5) with having an adverse effect on some aspects of QOL, like physical and mental health, which supports our finding, in which we found that patients taking less than 5 medications had higher scores in the environmental domain of QOL.39 The environmental domain measures financial status, security, safety, health care accessibility at home and institution, recreation and leisure, transportation, and the natural environment. The financial burden of polypharmacy may explain this finding, its toll on the patient’s activity, as well as potential adverse effects, anxiety overdosing and forgetting, limited transportation available to the elderly, and other factors.

We note certain limitations in our study, including a relatively small sample size and the conduction of the interview in the dialysis unit. In addition, the data were collected from one center (JUH), and a larger sample with multi-centres is required for more accurate results.

Conclusions

Chronic kidney disease and undergoing dialysis can impact patients beyond the physical symptoms associated with the disease. This research investigated how chronic kidney disease and dialysis impact patients beyond the physical symptoms associated with the disease. The study found that ESRD patients on dialysis are at a higher risk of experiencing depression, anxiety, and lower levels of quality of life. Factors such as age, gender, marital status, smoking, and taking more than five medications negatively impact dialysis patients’ psychological health and quality of life. The study suggests that care providers should not only treat the disease but also focus on treating the patient as a whole, with proper counselling, referral to specialists, and continuous follow-up to ensure more effective psychiatric patient care. Education, support, and stress-free environments are essential, and smoking should be discouraged. The research highlights the need for regular screening and prevention of psychiatric diseases, especially for patients more vulnerable to psychological illness, such as older adults, females, and singles. Finally, the study emphasizes that improving quality of life should focus on all aspects and not just one. higher.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Jordan University Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the method was carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Abbasi MA, Chertow GM, Hall YN. End-stage renal disease. BMJ Clin Evid. 2010;2010:2002.

2. Khalil AA, Khalifeh AH, Al-Rawashdeh S, Darawad M, Abed M. Depressive symptoms, anxiety, and quality of life in hemodialysis patients and their caregivers: a dyadic analysis. Jpn Psychol Res. 2021;53:1.

3. Ng HJ, Tan WJ, Mooppil N, Newman S, Griva K. Prevalence and patterns of depression and anxiety in hemodialysis patients: a 12-month prospective study on incident and prevalent populations. Br J Health Psychol. 2015;20(2):374–395. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12106

4. Kraus MA, Fluck RJ, Weinhandl ED, et al. Intensive hemodialysis and health-related quality of life. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(5s1):S33–s42. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.05.023

5. Goh ZS, Griva K. Anxiety and depression in patients with end-stage renal disease: impact and management challenges - a narrative review. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2018;11:93–102. doi:10.2147/IJNRD.S126615

6. Moreira JM, da Matta SM, Melo e Kummer A, Barbosa IG, Teixeira AL, Simões e Silva AC. Neuropsychiatric disorders and renal diseases: an update. J Bras Nefrol. 2014;36(3):396–400. doi:10.5935/0101-2800.20140056

7. Shirazian S, Grant CD, Aina O, Mattana J, Khorassani F, Ricardo AC. Depression in chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease: similarities and differences in diagnosis, epidemiology, and management. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2(1):94–107. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2016.09.005

8. Turkistani I, Nuqali A, Badawi M, et al. The prevalence of anxiety and depression among end-stage renal disease patients on hemodialysis in Saudi Arabia. Ren Fail. 2014;36(10):1510–1515. doi:10.3109/0886022X.2014.949761

9. Liu WJ, Musa R, Chew TF, Lim CT, Morad Z, Bujang A. Quality of life in dialysis: a Malaysian perspective. Hemodial Int. 2014;18(2):495–506. doi:10.1111/hdi.12108

10. Kocalevent RD, Hinz A, Brähler E. Standardization of the depression screener patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(5):551–555. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.04.006

11. Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the generalized anxiety disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46(3):266–274. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093

12. World Health Organization, Depressive disorder (depression); 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression.

13. Chronic Illness and Mental Health. Recognizing and treating depression, national institute of mental health (NIH). Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/chronic-illness-mental-health.

14. Gerontoukou E-I, Michaelidoy S, Rekleiti M, Saridi M, Souliotis K. Investigation of anxiety and depression in patients with chronic diseases. Health Psychol Res. 2015;3(2):2123. doi:10.4081/hpr.2015.2123

15. Alshelleh S, Alhouri A, Taifour A, et al. Prevelance of depression and anxiety with their effect on quality of life in chronic kidney disease patients. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):17627. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-21873-2

16. Sevinc M, Hasbal NB, Sakaci T, et al. Frequency of depressive symptoms in Syrian refugees and Turkish maintenance hemodialysis patients during COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0244347. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0244347

17. Al-Shammari N, Al-Modahka A, Al-Ansari E, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and their associations among end-stage renal disease patients on maintenance hemodialysis: a multi-center population-based study. Psychol Health Med. 2021;26(9):1134–1142. doi:10.1080/13548506.2020.1852476

18. Delgado-Domínguez CJ, Sanz-Gómez S, López-Herradón A, et al. Influence of depression and anxiety on hemodialysis patients: the value of multidisciplinary care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:7. doi:10.3390/ijerph18073544

19. Muhammad Jawad Zaidi S, Kaneez M, Awan J, et al. Sleep quality and adherence to medical therapy among hemodialysis patients with depression: a cross-sectional study from a developing country. B J Psych Open. 2021;7(S1):S43–S.

20. Al-Jabi SW, Sous A, Jorf F, et al. Depression among end-stage renal disease patients undergoing hemodialysis: a cross-sectional study from Palestine. Ren Replace Ther. 2021;7(1):12. doi:10.1186/s41100-021-00331-1

21. Muthukumaran A, Natarajan G, Thanigachalam D, Sultan SA, Jeyachandran D, Ramanathan S. The role of psychosocial factors in depression and mortality among Urban hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6(5):1437–1443. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2021.02.004

22. Ezzaki S, Failal I, Elafifi R, Elkhayat S, Elmedkouri G, Ramdani B. MO897ANXIETY AND DEPRESSIVE DISORDERS IN CHRONIC HEMODIALYSIS PATIENTS. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2021;36(Supplement_1):

23. Kizilcik Z, Sayiner FD, Unsal A, Ayranci U, Kosgeroglu N, Tozun M. Prevalence of depression in patients on hemodialysis and its impact on quality of life; 2012.

24. Shafipour V, Alhani F, Kazemnejad AJ. A survey of the quality of life in patients undergoing hemodialysis and its association with depression, anxiety and stress. J Nurs Midwifery Sci. 2015;2(2):29–35. doi:10.4103/2345-5756.231432

25. Lee M-J, Lee E, Park B, Park IJKR, Practice C. Mental illness in patients with end-stage kidney disease in South Korea: a nationwide cohort study. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2021;41(2):231. doi:10.23876/j.krcp.21.047

26. Noor MU, Kumar S, Junejo AM, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in hemodialysis patients of end stage renal disease. Rawal Med J. 2021;46(4):844–847.

27. Kamel Rae M, Goda TM. Anxiety and depression among hemodialysis patients in Egypt. Zagazig Vet J. 2022;28(3):594–604.

28. Bouali W, Gniwa RO, Soussia RB, Mohamed AH, Zarrouk LJ. Depression and anxiety disorders in chronic hemodialysis patients. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64(S1):S236–S7. doi:10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.633

29. AlNashri FI, Almutary HH, Al Nagshabandi EA. Impact of anxiety and depression on quality of life among patients undergoing hemodialysis: a scoping review. Evid Based Nurs. 2020;2(3):14. doi:10.47104/ebnrojs3.v2i3.134

30. El Filali A, Bentata Y, Ada N, Oneib BJ. Depression and anxiety disorders in chronic hemodialysis patients and their quality of life: a cross-sectional study about 106 cases in the northeast of Morocco. Saudi J Kid Dis Transp. 2017;28(2):341. doi:10.4103/1319-2442.202785

31. Bayat N, Alishiri GH, Salimzadeh A, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression: a comparison among patients with different chronic conditions. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16(11):1441.

32. Al-Ali F, Elshirbeny M, Hamad A, et al. Prevalence of depression and sleep disorders in patients on dialysis: a cross-sectional study in Qatar. Int J Nephrol. 2021;2021:1–7. doi:10.1155/2021/5533416

33. Khan A, Khan AH, Adnan AS, Sulaiman SAS, Mushtaq SJ. Prevalence and predictors of depression among hemodialysis patients: a prospective follow-up study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–13. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-6796-z

34. Altemus M, Sarvaiya N, Epperson CN. Sex differences in anxiety and depression clinical perspectives. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014;35(3):320–330. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.05.004

35. Al Awwa IA, Jallad SG. Prevalence of depression in Jordanian hemodialysis patients. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2018;12:2. doi:10.5812/ijpbs.11286

36. Teles F, Azevedo VF, Miranda CT, Miranda MP, Teixeira M, Elias RM. Depression in hemodialysis patients: the role of dialysis shift. Clinics. 2014;69:198–202. doi:10.6061/clinics/2014(03)10

37. Pilger C, Santos R, Lentsck MH, Marques S, Kusumota LJ. Spiritual well-being and quality of life of older adults in hemodialysis. Rev Bras Enferm. 2017;70:689–696. doi:10.1590/0034-7167-2017-0006

38. Teles F, Amorim de albuquerque AL, Freitas Guedes Lins IK, et al. Quality of life and depression in haemodialysis patients. Psychol Health Med. 2018;23(9):1069–1078. doi:10.1080/13548506.2018.1469779

39. Bujang MA, Musa R, Liu WJ, Chew TF, Lim CT, Morad ZJ. Depression, anxiety and stress among patients with dialysis and the association with quality of life. Asian J Psychiatr. 2015;18:49–52. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2015.10.004

40. Coombs RH. Marital status and personal well-being: a literature review. Fam Relat. 1991;40(1):97–102. doi:10.2307/585665

41. Ma TK-W, Li PK-T. Depression in dialysis patients. Nephrology. 2016;21(8):639–646. doi:10.1111/nep.12742

42. Hamody AR, Kareem AK, Al-Yasri AR, Sh Ali AA. Depression in Iraqi hemodialysis patients. Arab J Nephrol Transplant. 2013;6(3):169–172.

43. Yaseen M, Naqvi S, Ali M. Depression and anxiety in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;46(4):838–843.

44. Kaneez M, Zaidi SMJ, Zubair AB, et al. Sleep quality and compliance to medical therapy among hemodialysis patients with moderate-to-severe depression: a cross-sectional study. Cureus. 2021;13:2.

45. Sethi S, Menon A, Dhooria HPS, et al. Evaluation of health-related quality of life in adult patients on hemodialysis. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2021;11(4):221. doi:10.4103/ijabmr.ijabmr_237_21

46. Molsted S, Wendelboe S, Flege MM, Eidemak I. The impact of marital and socioeconomic status on quality of life and physical activity in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrology. 2021;53(12):2577–2582.

47. Tuna Ö, Balaban ÖD, Mutlu C, Şahmelikoğlu Ö, Bali M, Ermis C. Depression and cognitive distortions in hemodialysis patients with end stage renal disease: a case-control study. Eur J Psychiatry. 2021;35(4):242–250. doi:10.1016/j.ejpsy.2021.01.001

48. Thomas A, Jacob JS, Abraham M, Thomas BM, Ashok P. Assessment of acute complications and quality of life in hemodialysis patients with chronic kidney disease. Res J Pharm Technol. 2021;14(5):2671–2675. doi:10.52711/0974-360X.2021.00471

49. Alshraifeen A, Al‐Rawashdeh S, Alnuaimi K, et al. Social support predicted quality of life in people receiving haemodialysis treatment: a cross‐sectional survey. Nurs Open. 2020;7(5):1517–1525. doi:10.1002/nop2.533

50. Pan K-C, Hung S-Y, Chen C-I, Lu C-Y, Shih M-L, Huang C. Social support as a mediator between sleep disturbances, depressive symptoms, and health-related quality of life in patients undergoing hemodialysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0216045. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0216045

51. Ma SJ, Wang WJ, Tang M, Chen H, Ding F. Mental health status and quality of life in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. Ann Palliat. 2021;10:6112–6121. doi:10.21037/apm-20-2211

52. Cohen SD, Cukor D, Kimmel P. Anxiety in patients treated with hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(12):2250–2255. doi:10.2215/CJN.02590316

53. Abdo N, Sweidan F, Batieha AJP. Quality-of-life among Syrian refugees residing outside camps in Jordan relative to Jordanians and other countries. PeerJ. 2019;7(e6454):e6454. doi:10.7717/peerj.6454

54. Pereira RJ, Cotta R, Franceschini S, et al. Influência de fatores sociossanitários na qualidade de vida dos idosos de um município do Sudeste do Brasil. Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2011;16(6):2907–2917. doi:10.1590/S1413-81232011000600028

55. Al Kasanah A, Umam FN, Putri M. Factors Related to Quality of Life in Hemodialysis Patients. J Ilmu Keperawatan. 2021;4(4):709–714.

56. Reza IF. Implementasi coping religious dalam mengatasi gangguan fisik-psikis-sosial-spiritual pada pasien gagal ginjal kronik. Intizar. 2016;22(2):243–280. doi:10.19109/intizar.v22i2.940

57. Rostami Z, Einollahi B, Lessan-Pezeshki M, et al. Health-related quality of life in hemodialysis patients: an Iranian multi-center study. Nephrourol Mon. 2013;5(4):901. doi:10.5812/numonthly.12485

58. Bayoumi M, Al Harbi A, Al Suwaida A, Al Ghonaim M, Al Wakeel J, Mishkiry A. Predictors of quality of life in hemodialysis patients. Saudi J Kid Dis Transp. 2013;24(2):254–259. doi:10.4103/1319-2442.109566

59. Pakpour AH, Saffari M, Yekaninejad MS, Panahi D, Harrison AP, Molsted S. Health-related quality of life in a sample of Iranian patients on hemodialysis. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2010;4(1):50–59.

60. Sullivan JD, Bashir A, Qadeer A, Khan M, S K. Assessment of quality of life in patients with end stage renal failure using KDQOL-SF. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2021;6(1):015–22.

61. Goyal E, Chaudhury S, Saldanha D. Psychiatric comorbidity in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Ind Psychiatry J. 2018;27(2):206–212. doi:10.4103/ipj.ipj_5_18

62. Wu Y-H, Hsu Y-J, Tzeng W. Physical activity and health-related quality of life of patients on hemodialysis with comorbidities: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(2):811. doi:10.3390/ijerph19020811

63. Samoudi AF, Marzouq MK, Samara AM, Zyoud S, Al-Jabi SW, Outcomes Q. The impact of pain on the quality of life of patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis: a multicenter cross-sectional study from Palestine. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s12955-021-01686-z

64. Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey G. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2023 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.