Back to Journals » Orthopedic Research and Reviews » Volume 10

Irreparable rotator cuff tears: challenges and solutions

Authors Novi M , Kumar A, Paladini P , Porcellini G, Merolla G

Received 4 July 2018

Accepted for publication 8 November 2018

Published 5 December 2018 Volume 2018:10 Pages 93—103

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/ORR.S151259

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Clark Hung

Michele Novi,1 Avinash Kumar,2 Paolo Paladini,3 Giuseppe Porcellini,4 Giovanni Merolla3,5

1Orthopaedic and Trauma Unit, University Hospital of Pisa, Pisa, Italy; 2Department of Orthopaedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, India; 3Shoulder and Elbow Unit, “D. Cervesi” Hospital, AUSL della Romagna, Ambito Territoriale di Rimini, Rimini, Italy; 4Orthopaedic and Trauma Unit, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Policlinico di Modena, Modena, Italy; 5“Marco Simoncelli” Biomechanics Laboratory, “D. Cervesi” Hospital, AUSL della Romagna, Ambito Territoriale di Rimini, Rimini, Italy

Abstract: Irreparable rotator cuff tears are common conditions seen by shoulder surgeons, characterized by a torn and retracted tendon associated with muscle atrophy and impaired mobility. Direct fixation of the torn tendon is not possible due to the retracted tendon and lack of healing potential which result in poor outcome. Several treatment options are viable but correct indication is mandatory for a good result, pain improvement, and restoration of shoulder function. Patient can be treated either with a conservative program or surgically when necessary, by different available modalities like arthroscopic debridement, partial reconstruction, subacromial spacer, tendon transfer, and shoulder replacement with reverse prosthesis. The aim of this study was to review literature to give an overview of the available possible solutions, with indications and expected outcomes.

Keywords: irreparable rotator cuff tear, arthroscopy, partial repair, tendon transfer, graft augmentation

Introduction

Rotator cuff tears (RCTs) represent one of the most frequent pathologic conditions of the shoulder, with a higher incidence in patients over 50 years and a progressive pattern in most of the cases.1

Surgical treatment for symptomatic cases provides direct reattachment of the torn tendon to the humeral footprint; however, it cannot be achieved when progression of RCT develops into an irreparable condition.

The term “irreparable” is often incorrectly used and interchanged with the term massive; while most irreparable RCTs can also be considered massive tears, not all massive tears are indeed irreparable.2 RCTs are defined as irreparable when the lesions cannot be repaired primarily to their insertion on the tuberosities despite conventional techniques of surgical release/mobilization, because of their size, retraction, and muscle impairment caused by atrophy and fatty infiltration.3,4

For posterosuperior RCTs, Gerber et al considered the tear as irreparable when it was impossible to achieve fixation of torn tendons in <60° of abduction despite adequate releases.5

Clinical aspects of an irreparable RCT include long duration of symptoms, weakness in external rotation, reduction of acromiohumeral distance <6 mm on a true anteroposterior X-ray, torn tendon with retraction to the glenoid (stage 3 of Patte classification), and fatty infiltration of the rotator cuff muscles >50%.6

These factors correlate with a high probability that the tendons will not heal even if mobilization and repair are feasible. So, irreparable lesions are considered to be those that have low healing potential, and those wherein standard surgical approaches for RCT are not successful.

Literature reports of retear rates in massive posterosuperior rotator cuff repair range from 40% to 91%.7–9 Anterosuperior RCTs, more specifically subscapularis (SSc) tears, are less common than the posterosuperior RCTs.10,11

The purpose of this paper was to review literature to give an overview of the currently available solutions, with indications and expected outcomes for irreparable RCTs. This manuscript is not a systemic review and draws from the clinical experience of the authors and with the current literature evidence on this topic.

Conservative treatment

A massive RCT has been historically reported as a tear with a diameter of ≥5 cm or as a complete tear of two or more tendons. A recent classification of massive tears described five types: type A, supraspinatus and superior SSc tears; type B, supraspinatus and entire SSc tears; type C, supraspinatus, superior SSc, and infraspinatus tears; type D, supraspinatus and infraspinatus tears; and type E, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor tears. This classification not only subclassifies massive tears but has also been linked to function, particularly the maintenance of active elevation. The limit between massive and irreparable tears is often “transient.”7–11 Irreparable cuff tear in low-demanding patients can be treated conservatively with the aim of improving pain, and full or partial recovery of the shoulder motion. Patients should follow a rehabilitation program, taking medication and physical therapy to reduce pain and subacromial injections with steroids, hyaluronic acid, or platelet-rich plasma. In some patients this treatment is effective, although it is possible that the attenuation or the disappearance of pain is simply due to rest and/or the natural history of the cuff tear.12

Good results with physical therapy for patients with irreparable RCTs are reported in the literature. Ainsworth evaluated a multimodal 12-week physical therapy program that emphasized on patient education, posture correction, re-education of muscle recruitment, strengthening, stretching, improved proprioception, and adaptation.13 Authors have reported nine points of improving on the Oxford Shoulder Score and 22 points of improving on the Short Form-36 score.

Exercises for strengthening anterior deltoid help in achieving shoulder elevation even in patients who originally present with pseudoparalytic shoulder (elevation below 90°). A 9-month prospective study by Levy et al in 17 patients with a diagnosis of irreparable RCTs treated with an anterior deltoid training program, continued for 12 weeks, showed a mean constant score (CS) improvement from 26 to 63, and a forward flexion improvement from 40° to 160°.14

Even other authors have concluded that nonoperatively treated massive RCTs in moderately symptomatic patients can maintain satisfactory shoulder function despite the progression of degenerative pathology.15

Arthroscopic debridement

Arthroscopic procedures in irreparable RCTs are effective at alleviating pain, but have little effect on strength.6

The subacromial bursa contains inflammatory cytokines correlated with algogenic effect. Chronic inflammatory infiltrate, such as synovial-like cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, plasmacytes, young fibrocytes, and sometimes dystrophic calcifications are presents in the tear margins.16

Therefore, bursectomy and debridement of tear margins may determine pain decrease.

Acromioplasty, subacromial decompression, and debridement of massive infraspinatus and supraspinatus tears reported good results in the literature with an improvement of mobility, pain, and clinical scores.17,18

Acromioplasty is, however, a less appealing procedure in arthroscopic debridement because inevitably it causes the disruption of the coracoacromial ligament and is therefore an incentive for humeral head escape.18

A retrospective study by Liem et al19 assessed 31 patients after arthroscopic debridement of an irreparable RCT with a mean follow-up of 4 years. They observed that the mean American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score significantly improved from 24 points preoperatively to 70 points at follow-up. Scores for pain were reduced from 8 to 3 points on a visual analog scale ranging from 0 to 10.

Several studies showed that this is a viable option in the elderly and low-demand patients, even if it does not slow the progression of osteoarthritis.20 However, satisfactory results are most likely to be achieved in the elderly and low-demanding patients seeking primarily pain relief and in patients with a preserved deltoid function and intact posterior cuff.

Long head biceps tendon tenotomy

Patients with a massive cuff tear usually have a degenerated, frayed, and flattened biceps tendon. Clinical presentation is often intense anterior pain with positive tests for biceps tendinitis. Walch et al observed that many patients with chronic RCTs had pain relief after spontaneous rupture of the biceps tendon.21

Tenotomy may be performed close to the origin on the glenoid to avoid impingement of the stump with the glenohumeral articulation. Moreover, the flattened part of the tendon is flattened stucks at the entrance of the bicipital groove without causing the Popeye deformity.

Other authors report that additional tenotomy of the long head biceps tendon during arthroscopic debridement did not significantly influence the postoperative results at long-term follow-up.22,23

Suprascapular nerve (SSN) release

In cases of RCT associated with SSN neuropathy and related positive clinical and electromyography (EMG) signs, surgical nerve release is increasingly performed.

SSN neuropathy seems to be associated with pain and weakness in massive RCTs, but its pathogenesis is not fully understood.

Some articles show different results, like the prospective study of Collin et al in 2014, where the authors founded a low association of neuropathy with massive RCT.24

A possible explanation of SSN neuropathy is that massive posterosuperior cuff tears can place traction on the SSN as the rotator cuff muscles retract. Some authors reported abnormal nerve conduction studies, in patients with fatty infiltration and tendon retraction (Patte stage 3).25 Some of these studies also documented partial or complete recovery following partial or complete repair.

It is possible that nerve entrapment is caused by a possible adhesion related to the scar tissue of the tear and fatty infiltration, with an abnormal traction by the pathologic stump of the tendon.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred modality to evaluate atrophy of the cuff muscles as well as to assess potential causes of SSN compression. EMG and nerve conduction velocity studies remain the gold standard for formulation of the diagnosis of suprascapular neuropathy.26

The first-line treatment is usually conservative,27 consisting of rest, physical therapy, and anti-inflammatory drugs. Surgical treatment is considered for patients with nerve compression by an external source or for symptoms refractory to conservative measures.

Tuberoplasty

Fenlin et al28 introduced in 2002 a new surgical open procedure described as tuberoplasty, modified by Scheibel et al29 2 years later with an arthroscopic approach called “reversed subacromial decompression.”

It involves removing the exuberant lateral margin of the greater tuberosity to create a smooth congruent acromiohumeral articulation and preserving the integrity of the coracoacromial arch.

Significant improvement in pain, activities of daily living, and range of motion are reported, and an increase of age-adjusted CS from 65.9% to 90.6%, with a mean follow-up of 40 months. A progression of osteoarthritis was observed by the authors, although it did not interfere with the clinical result.

Subacromial biodegradable spacer

The subacromial spacer is a biodegradable balloon (OrthoSpace, Kfar Saba, Israel) made of poly-L-lactide, arthroscopically implanted between the acromion and the humeral head, and inflated with saline solution. It is derived from general surgery devices, used on top of the massive cuff tear, and its presence reduces subacromial friction during shoulder abduction by lowering the head of the humerus and facilitating humeral gliding against the acromion.

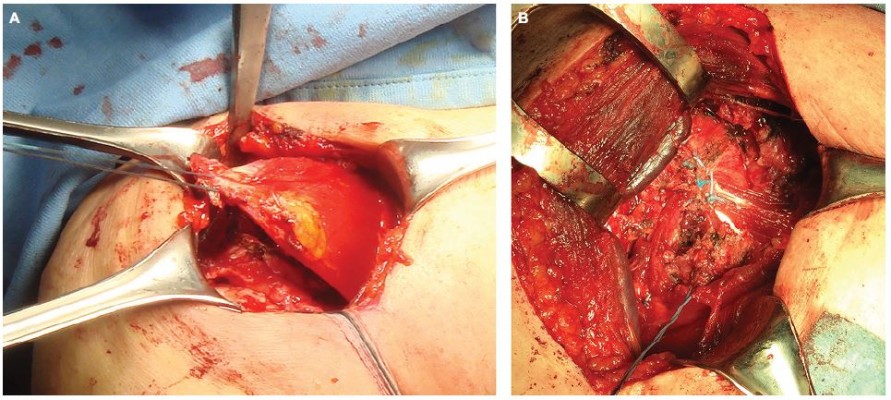

Debridement and bursectomy are performed to define the dimension of the RCT and measure the correct size (Figure 1A and B). The InSpace subacromial spacer is available in three different sizes: small (40×50 mm), medium (50×60 mm), and large (60×70 mm).

| Figure 1 Subacromial biodegradable spacer implantation. (A) Probe used to choose the size of the spacer. (B) Subacromial spacer inflated with saline solution at the end of the arthroscopic procedure. |

The spacer deflates in ~10 weeks and completely degrades within 15 months,30 a sufficient period of time to perform physiotherapy program. It is not clear why pain and functional scores continue to improve beyond the period of spacer disintegration. However, the spacer preserves the acromiohumeral distances optimizing the balance on the humeral head and consequent improvement of pain.31

Partial rotator cuff repair

The biomechanical concept of the “suspension bridge” in the rotator cuff was introduced for the first time by Burkhart et al,32 in 1993, leading to the hypothesis of the functional rotator cuff and the possibility for a functional partial repair of the cuff tear.

Repair has to include the whole SSc as well as the inferior half of infraspinatus at least, in order to restore the transverse force couples and a stable fulcrum for physiologic glenohumeral kinematics (Figure 2).

| Figure 2 Arthroscopic partial repair of the posterior bundle of the rotator cuff (infraspinatus tendon) with a triple suture anchor. |

Porcellini et al33 showed with their study that the CS of the patients improved from 44 to 73 points and the Simple Shoulder Test from 4.6 to 9. The acromion humeral distance increased from 6.1 to 9.1 mm. They stated that “partial” functional repair of the infraspinatus, leaving the greater tuberosity uncovered, gives good results in terms of patient satisfaction and in restoring the acromion humeral distance.

Tendon transfer procedures

The choice of the most appropriate tendon transfer depends on several aspects such as the clinical presentation (pain or disability), age of the patient, functional demand, medical comorbidities, joint stability, and presence of arthritis. The ideal candidate for a tendon transfer procedure is a young, active patient with a severe disability related to weakness and loss of rotation, without glenohumeral osteoarthritis.34–36 The selection of the donor muscle is based on the structural deficit and impaired function that we want to restore.

Posterosuperior irreparable cuff tears are commonly treated with the latissimus dorsi (LD) tendon transfer, while for irreparable anterosuperior tears pectoralis major (PMa) tendon transfer is used.37,38

Other procedures include LD and teres major transfer (L’Episcopo procedure), lower trapezius (LT) transfer, and pectoralis minor (PMi) transfer.

LD transfer

LD transfer provides a large, vascularized tendon from a muscle that originally contributes to internal rotation, retroversion, and abduction of the shoulder joint.

The tendon detached and transferred to close a posterosuperior cuff defect changes its function to exert an external rotational moment and depression of the humeral head, allowing more effective action of the deltoid muscle in abduction.

Originally described by Gerber et al39 in 1988, LD tendon transfers were firstly used in patients with brachial palsy in order to treat the lack of external rotation.

Inclusion criteria are patients with posterosuperior irreparable cuff tear, muscle atrophy, and fatty infiltration, with an impairment of abduction and external rotation.

The irreparable supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons are typically torn with retraction to the level of the glenoid (Patte stage 3), and at clinical examination, patients present positive drop-arm and external rotation lag tests.40 At the MRI assessment, fatty infiltration should present Goutallier grade >3.

Exclusion criteria are patients with SSc tendon tear (Lafosse >2), eccentric arthritis (Hamada >4), pseudoparalytic shoulder, deltoid dysfunction, and atrophic teres minor.

The SSc tendon should be intact and functioning indeed, as forward elevation and glenohumeral stability drastically decrease with SSc insufficiency.41

Approaches described for the transfer include two-incision technique,39 single incision, and arthroscopy-assisted procedure (Figure 3A–D). Habermeyer et al42 described a single V-shaped incision approach for direct visualization of the posterior humeral head and transfer of the tendon in a more posterior position.

In the majority of patients LD tendon transfer is very effective in reducing pain; however, the functional outcome is more variable.43 Correct indications and patient selection are crucial.

Long-term follow-up reported by Gerber39 shows an average increase in the subjective shoulder value from 29% preoperatively to 70%, an increase of the mean CS from 56% to 80%, and an improvement of pain score from 7 to 13 points. Mean flexion increased from 118° to 132°, abduction from 112° to 123°, and external rotation from 18° to 33°. Poor results occurred in shoulders with insufficiency of the SSc muscle and fatty infiltration of the teres minor muscle.

L’Episcopo procedure

In 1934, L’Episcopo44 described a combined teres major and LD transfer for obstetric brachial plexus palsy, changing their function from internal to external rotators as well as humeral depressor.

A modified L’Episcopo technique was proposed in 2002 by Habermeyer et al45 with the indication to restore loss of external rotation in patients with massive posterosuperior RCT. Boileau et al46 published in 2007 early results of their single-incision modified L’Episcopo technique, using a delto-pectoral approach in beach chair position, with few complications, greater external rotation owing to addition of the teres major transfer and possibility to associate it with reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

PMa transfer

SSc tears have less frequent incidence than the posterosuperior RCTs.

SSc acts as the primary internal rotator and anterior dynamic stabilizer. Patients with SSc RCTs typically present with anterior shoulder pain, internal rotation weakness, and dysfunction, associated with belly-press, bear-hug, and lift-off positive tests.47 The outcomes of direct repair of chronic SSc tears with fatty infiltration, Goutallier grade ≥3, are poor.48,49 In these cases, a tendon transfer with PMa is a possible treatment for restoring internal rotation forces.

PMa flexes, internally rotates, and adducts the humerus. Ideal patients for this transfer are those with an irreparable anterosuperior cuff tear with minimal glenohumeral joint arthritic changes and a functioning deltoid muscle, age <65, intact or reparable posterosuperior RCTs.37,50

PMa can be transferred anterior to the conjoined tendon as originally described in 1997 by Wirth and Rockwood48 or only the superior two-thirds of the tendon can be transferred under the conjoined tendon as described by Resch et al37 (Figure 4A and B).

| Figure 4 Pectoralis major (PMa) tendon transfer. (A) PMa tendon detachment from the humerus insertion and muscle belly release. (B) Fixation on the lesser tuberosity of the humerus. |

In 2001, Warner described a transfer using the inferior sternal head attachment under the clavicular head but anterior to the conjoined tendon to avoid injury to the musculocutaneous nerve.51

Despite good outcomes reported by several authors, no comparative studies have been performed to compare the different techniques.

Resch et al37 and then Galatz et al52 reported satisfactory results after subcoracoid transfer of the PMa tendon with a massive RCT with improvement in pain and function (ASES scores improved from 27.2 to 47.7).

PMi transfer

The PMi tendon as a graft to treat irreparable SSc tears was first used by Wirth and Rockwood,48 who even tried to use the coracohumeral ligament.

PMi transfer is indicated in irreparable RCT involving the upper two-thirds of the SSc tendon.

Paladini et al53 used a subcoracoid PMi transfer with a small piece of the coracoid for tears of the superior two-thirds of SSc associated with irreparable supraspinatus tears (Figure 5A and B). At 2 years of follow-up, 27 patients demonstrated good outcome with significant improvement in CS and 78% of them returned to their daily activity.

LT transfer

Historically, the trapezius is the most common tendon transfer performed for adult patients with brachial plexus injury.54 In 2009, Elhassan et al55 performed the transfer of middle trapezius and LT to restore shoulder external rotation in a patient with brachial plexus injury. This technique has been proposed also for patients with irreparable posterosuperior cuff tears.56 LT is grafted from an incision medial to the scapula, then augmented with an Achilles’ tendon allograft, passed underneath the deltoid and infraspinatus, and positioned on the infraspinatus footprint. One of the problems about transferring part of the trapezius could be loss of the stabilizing effect of this muscle on the scapula. However, if the serratus anterior is functioning normally, then the risk of scapular winging is low.55 Elhassan et al reported a significant improvement in active abduction, flexion, and external rotation. At an average follow-up of 47 months, 32 out of 33 patients had significant improvement in the pain levels, an average forward flexion of 120°, abduction of 90°, and external rotation of 50° (range, 20°–70°; P<0.01). A biomechanical study published by Hartzler et al,57 using a novel shoulder model, compared the moment arm of external rotation of the LD, teres major, and LT transfers. They showed that LT had the largest moment arm of external rotation and that the LD transfer had the lowest moment arm of external rotation with the shoulder adducted. The LD becomes potentially the most efficient transfer for external rotation with the arm abducted. Omid et al58 also stated, in their biomechanical study on cadaveric shoulders, that the LT transfer is biomechanically superior to the latissimus transfer in restoring native glenohumeral biomechanics and joint reaction forces in both the compressive distractive and anterior–posterior planes.

Interposition allografts

There have been reports of using fascia lata or human dermal allograft interposed in massive or irreparable RCT (Figure 6). Dimitrios et al in 2015 have shown improvement in pain and CS (from 32.5 to 88.7) in 68 patients treated with interposition of fascia lata allograft for irreparable RCT with a follow-up of 12 months. At the end of 12 months ultrasound examination of 30 patients showed that only three of the patients had retear.61 Pandey et al in 2017 showed in their prospective nonrandomized cohort study of 26 patients having symptomatic irreparable RCT, managed with partial repairs in the first half of patients and with partial repair along with interposition GraftJacket dermal allograft in the second half of patients, that the postoperative scores for the latter group were significantly higher than the former group. The Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS) improved from 14.9 to 43.9 in the dermal allograft group in comparison to 17.8–37.1 OSS only in the partial repair group. The CS improved from 41.2 to 83.9 in the dermal allograft group while it changed from 43.1 to 70.8 in the former group.62

| Figure 6 Intraoperative findings of arthroscopic massive rotator cuff repair with dermal allograft augmentation (interposition allograft). |

Interposition autografts

Mori et al in 2015 have shown that partial repair with interposition of fascia lata autograft improved CS, ASES scores, and range of motion in irreparable RCTs with high-grade (Goutallier stage 3 or 4) supraspinatus fatty degeneration and low-grade (Goutallier stage 1 or 2) infraspinatus fatty degeneration in comparison to irreparable RCTs with high-grade both supraspinatus and infraspinatus fatty degeneration treated with the same procedure after a follow-up of 24 months.63

Mihara et al used iliotibial band with a Gerdy’s tubercle bone block autograft for irreparable RCTs and have shown that the bone block unites with the greater tubercle at 3–4 months, confirmed on computed tomography, and after 24 months of follow-up there is significant improvement in pain, subjective scores, and range of motion. They also highlighted that there was no donor site morbidity.64

Superior capsular reconstruction (SCR)

There is an additional defect of superior capsule in patients with irreparable RCT affecting the movements of the humeral head in all directions in addition to the movement on the side of lesion, which has been termed as “circle concept” and this adds to the shoulder instability in such irreparable RCTs.65,66 Mihata et al in their seminal paper described the technique of SCR where they completely repaired the SSc tendon and partially repaired the infraspinatus and teres minor tendons. After this, the fascia lata autograft, 6–8 times folded, was introduced in the joint folded and was medially fixed to the superior glenoid with two suture anchors and was fixed laterally to the greater tuberosity using the compression double-row technique. The graft was also sutured posteriorly to the infraspinatus tendon and anteriorly to the residual supraspinatus or SSc tendons for a better force–couple moment, suturing the tendons to the graft side to side.67 After a follow-up of 24–51 months (mean 34.1 months), there was an increase in ASES, Japanese Orthopaedic Association, and University of California at Los Angeles scores from 23.5 to 92.9, from 48.3 to 92.6, and from 9.9 to 32.5, respectively. Forward flexion, external rotations were also improved after 24 months. The acromiohumeral distance increased from 4.6 to 8.7 mm, thereby improving the instability.

There have been different techniques for graft introduction into the joint such as the double pulley system, two double pulley system, zip line shuttle, arthroscopic knot pusher, or by traction on a single suture anchor.68

Chillemi et al have used the proximal long head of biceps as an autograft after tenotomy, two medial suture anchors to the superior glenoid, and two lateral transosseous tunnel to fix the autograft.69

The indications for this surgery are young patients with massive irreparable posterosuperior RCTs with no arthritis. There is generally Goutallier stage ≥3 fatty degeneration with retraction of supraspinatus or infraspinatus tendons going up to the glenoid or just medial to it.68

Fixed high riding humeral head is a contraindication for the surgery but if the humeral head can be reduced to its normal position by performing sulcus maneuver SCR can be done as this indicates that there is sufficient mobility which can be stabilized by the SCR autograft.68

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA)

RTSA is the first choice of treatment to improve elevation in patients with a true pseudoparalytic shoulder, irreparable RCT, glenohumeral osteoarthritis, who are not candidates for arthroscopic procedures or tendon transfers.

Even though the indications for RTSA have been expanded to treat a number of pathologies with an average good outcome, the best results in terms of functional and clinical outcomes after reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) are obtained in patients with RCT arthropathy. Wall et al59 presented in 2007 a review of the results of RSA according to different etiologies. The study showed an increase of CS from 27.8 preoperatively to 63.4 in patients treated with RSA in massive RCTs. In a systematic review in 2017, Petrillo et al70 confirmed a statistically significant improvement in all clinical scores and shoulder mobility, with some limits in external rotation. However, they reported high perioperative complication rates, resulting in an increased number of revision surgeries. Among these complications noticeable ones were mechanical failure (2.4%), acromion fractures (2.7%), infections (0.9%), and heterotopic ossification (6.6%). In patients with associated positive external rotation lag sign or Hornblower sign, LD transfer or LD teres major transfer could be associated to RSA.46,59 The above-mentioned good results of Boileau et al have been confirmed in a 2-year follow-up study published in 2013 by Boughebri et al.60

Conclusion

Irreparable RCTs are a common condition which shoulder surgeons have to deal with. Over the years several treatment options have been proposed, but the real challenge is to apply the correct indication for the correct procedure for each patient. Patients without anterosuperior migration of the humeral head should initially be treated conservatively with physical therapy and anterior deltoid strengthening. Patients nonresponsive to conservative treatment, complaining of pain and impairment of elevation, should undergo injection of local anesthetics and steroids to assess if the pseudoparalysis is due to pain.

Literature confirms that in patients, with a painful shoulder with irreparable RCT, who are not able to elevate the arm (even after steroid injection), arthroscopic debridement is indicated; biceps tenotomy, partial repair, and SSN release can also be performed, according to MRI and EMG findings.

The subacromial biodegradable spacer is a device that is helpful to restore the acromiohumeral height, improving the balance forces across the humeral head. Even if the spacer deflates and reabsorbs, it lasts sufficiently (~15 months) for an efficient physical therapy program.

Patients who have chronic posterosuperior cuff tear and loss of external rotation, but with conserved elevation and an intact SSc, are suited for LD transfer. In chronic anterosuperior cuff tear, with an intact superior cuff and no humeral escape, PMa or pectoral minor is indicated. Tendon transfers are complex surgical procedures that require a long period of rehabilitation. They do not restore normal shoulder function and kinematics, but can rather be considered as salvage procedures. Massive irreparable posterosuperior RCTs even with SSc tear can be managed with SCR also. Reverse shoulder prosthesis is indicated in patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis, irreparable RCT, and pseudoparalytic shoulder. The schematic diagram in Figure 7 illustrates a reasonable approach in the management of irreparable RCT.

| Figure 7 Schematic diagram describing therapeutic options for irreparable rotator cuff tears (RCTs). |

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Omid R, Lee B. Tendon transfers for irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(8):492–501. | ||

Rockwood CA, Williams GR, Burkhead WZ. Débridement of degenerative, irreparable lesions of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(6):857–866. | ||

Dines DM, Moynihan DP, Dines J, McCann P. Irreparable rotator cuff tears: what to do and when to do it; the surgeon’s dilemma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(10):2294–2302. | ||

Merolla G, Chillemi C, Franceschini V, et al. Tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears: indications and surgical rationale. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2015;4:425_432. | ||

Gerber C, Vinh TS, Hertel R, Hess CW. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of massive tears of the rotator cuff. A preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;232(232):51–61. | ||

Khair MM, Gulotta LV. Treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2011;4(4):208–213. | ||

Bartl C, Kouloumentas P, Holzapfel K, et al. Long-term outcome and structural integrity following open repair of massive rotator cuff tears. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2012;6(1):1–8. | ||

Kim SJ, Kim SH, Lee SK, Seo JW, Chun YM, Ym C. Arthroscopic repair of massive contracted rotator cuff tears: aggressive release with anterior and posterior interval slides do not improve cuff healing and integrity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(16):1482–1488. | ||

Duquin TR, Buyea C, Bisson LJ. Which method of rotator cuff repair leads to the highest rate of structural healing? A systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(4):835–841. | ||

Lyons RP, Green A. Subscapularis tendon tears. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13(5):353–363. | ||

Sakurai G, Ozaki J, Tomita Y, Kondo T, Tamai S. Incomplete tears of the subscapularis tendon associated with tears of the supraspinatus tendon: cadaveric and clinical studies. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(5):510–515. | ||

Gumina S, editor. Rotator Cuff Tear. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. | ||

Ainsworth R. Physiotherapy rehabilitation in patients with massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. Musculoskeletal Care. 2006;4(3):140–151. | ||

Levy O, Mullett H, Roberts S, Copeland S. The role of anterior deltoid reeducation in patients with massive irreparable degenerative rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(6):863–870. | ||

Zingg PO, Jost B, Sukthankar A, Buhler M, Pfirrmann CW, Gerber C. Clinical and structural outcomes of nonoperative management of massive rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(9):1928–1934. | ||

Gumina S, Di Giorgio G, Bertino A, della Rocca C, Sardella B, Postacchini F. Inflammatory infiltrate of the edges of a torn rotator cuff. Int Orthop. 2006;30(5):371–374. | ||

Rockwood CA Jr, Williams GR Jr, Burkhead WZ Jr. Débridement of degenerative, irreparable lesions of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(6):857–866. | ||

Gartsman GM. Massive, irreparable tears of the rotator cuff. Results of operative debridement and subacromial decompression. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(5):715–721. | ||

Liem D, Lengers N, Dedy N, Poetzl W, Steinbeck J, Marquardt B. Arthroscopic debridement of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(7):743–748. | ||

Gerber C, Wirth SH, Farshad M. Treatment options for massive rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(2 Suppl):S20–S29. | ||

Walch G, Edwards TB, Boulahia A, Nové-Josserand L, Neyton L, Szabo I. Arthroscopic tenotomy of the long head of the biceps in the treatment of rotator cuff tears: clinical and radiographic results of 307 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(3):238–246. | ||

Klinger HM, Spahn G, Baums MH, Steckel H. Arthroscopic debridement of irreparable massive rotator cuff tears--a comparison of debridement alone and combined procedure with biceps tenotomy. Acta Chir Belg. 2005;105(3):297–301. | ||

Pander P, Sierevelt IN, Pecasse G, van Noort A. Irreparable rotator cuff tears: long-term follow-up, five to ten years, of arthroscopic debridement and tenotomy of the long head of the biceps. Int Orthop. 2018;42(11):2633–2638. | ||

Collin P, Treseder T, Alexandre L, et al. Neuropathy of the suprascapular nerve and massive rotator cuff tears: a prospective electromyographic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(1):28–34. | ||

Kong BY, Kim SH, Kim DH, Joung HY, Jang YH, Oh JH. Suprascapular neuropathy in massive rotator cuff tears with severe fatty degeneration in the infraspinatus muscle. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(11):1505–1509. | ||

Vad VB, Southern D, Warren RF, Altchek DW, Dines D. Prevalence of peripheral neurologic injuries in rotator cuff tears with atrophy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(4):333–336. | ||

Shi LL, Freehill MT, Yannopoulos P, Warner JJ. Suprascapular nerve: is it important in cuff pathology? Adv Orthop. 2012;2012:516985–6. | ||

Fenlin Jm Jr, Chase JM, Rushton SA, Frieman BG. Tuberoplasty: creation of an acromiohumeral articulation-a treatment option for massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(2):136–142. | ||

Scheibel M, Lichtenberg S, Habermeyer P. Reversed arthroscopic subacromial decompression for massive rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(3):272–278. | ||

Holschen M, Brand F, Agneskirchner JD. Subacromial spacer implantation for massive rotator cuff tears: Clinical outcome of arthroscopically treated patients. Obere Extrem. 2017;12(1):38–45. | ||

Bozkurt M, Akkaya M, Gursoy S, Isik C. Augmented fixation with biodegradable subacromial spacer after repair of massive rotator cuff tear. Arthrosc Tech. 2015;4(5):e471–e474. | ||

Burkhart SS, Esch JC, Jolson RS. The rotator crescent and rotator cable: an anatomic description of the shoulder’s “suspension bridge”. Arthroscopy. 1993;9(6):611–616. | ||

Porcellini G, Castagna A, Cesari E, Merolla G, Pellegrini A, Paladini P. Partial repair of irreparable supraspinatus tendon tears: clinical and radiographic evaluations at long-term follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(7):1170–1177. | ||

Dines DM, Moynihan DP, Dines J, McCann P. Irreparable rotator cuff tears: what to do and when to do it; the surgeon’s dilemma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(10):2294–2302. | ||

Bedi A, Dines J, Warren RF, Dines DM. Massive tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(9):1894–1908. | ||

Namdari S, Voleti P, Baldwin K, Glaser D, Huffman GR. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(10):891–898. | ||

Resch H, Povacz P, Ritter E, Matschi W. Transfer of the pectoralis major muscle for the treatment of irreparable rupture of the subscapularis tendon. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(3):372–382. | ||

Gerber C, Rahm SA, Catanzaro S, Farshad M, Moor BK. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for treatment of irreparable pos- terosuperior rotator cuff tears: long-term results at a minimum follow-up of ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 20131926;6(95):1920. | ||

Gerber C, Vinh TS, Hertel R, Hess CW. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of massive tears of the rotator cuff. A preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;232(232):51–61. | ||

Hertel R, Ballmer FT, Lombert SM, Gerber C. Lag signs in the diagnosis of rotator cuff rupture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5(4):307–313. | ||

Werner CM, Zingg PO, Lie D, Jacob HA, Gerber C. The biomechanical role of the subscapularis in latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(6):736–742. | ||

Habermeyer P, Magosch P, Rudolph T, Lichtenberg S, Liem D. Transfer of the tendon of latissimus dorsi for the treatment of massive tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88-B(2):208–212. | ||

Iannotti JP, Hennigan S, Herzog R, et al. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Factors affecting outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(2):342–348. | ||

L’Episcopo JB. Tendon transplantation in obstetrical paralysis. Am J Surg. 1934;25(1):122–125. | ||

Habermeyer P, Magosch P, Lichtenberg S. The modified L’Episcopo procedure to reconstruct massive rotator cuff tears – a prospective study. In: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; February 13–17, 2002; Dallas, TX. | ||

Boileau P, Chuinard C, Roussanne Y, Neyton L, Trojani C. Modified latissimus dorsi and teres major transfer through a single delto-pectoral approach for external rotation deficit of the shoulder: As an isolated procedure or with a reverse arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(6):671–682. | ||

Gerber C, Krushell RJ. Isolated rupture of the tendon of the subscapularis muscle. Clinical features in 16 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(3):389–394. | ||

Wirth MA, Rockwood CA Jr. Operative treatment of irreparable rupture of the subscapularis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(A):722–731. | ||

Lyons RP, Green A. Subscapularis tendon tears. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13(5):353–363. | ||

Elhassan B, Ozbaydar M, Massimini D, Diller D, Higgins L, Warner JJ. Transfer of pectoralis major for the treatment of irreparable tears of subscapularis: does it work? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(8):1059–1065. | ||

Warner JJ. Management of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears: the role of tendon transfer. Instr Course Lect. 2001;50:63–71. | ||

Galatz LM, Connor PM, Calfee RP, Hsu JC, Yamaguchi K. Pectoralis major transfer for anterior-superior subluxation in massive rotator cuff insufficiency. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(1):1–5. | ||

Paladini P, Campi F, Merolla G, Pellegrini A, Porcellini G. Pectoralis minor tendon transfer for irreparable anterosuperior cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(6):e1–e5. | ||

Karev A. Trapezius transfer for paralysis of the deltoid. J Hand Surg Br. 1986;11(1):81–83. | ||

Elhassan B, Bishop A, Shin A. Trapezius transfer to restore external rotation in a patient with a brachial plexus injury. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(4):939–944. | ||

Elhassan BT, Wagner ER, Werthel JD. Outcome of lower trapezius transfer to reconstruct massive irreparable posterior-superior rotator cuff tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(8):1346–1353. | ||

Hartzler RU, Barlow JD, An KN, Elhassan BT. Biomechanical effectiveness of different types of tendon transfers to the shoulder for external rotation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(10):1370–1376. | ||

Omid R, Heckmann N, Wang L, McGarry MH, Vangsness CT, Lee TQ. Biomechanical comparison between the trapezius transfer and latissimus transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(10):1635–1643. | ||

Wall B, Nove-Josserand L, O’Connor DP, Edwards TB, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a review of results according to etiology. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(7):1476–1485. | ||

Boughebri O, Kilinc A, Valenti P. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty combined with a latissimus dorsi and teres major transfer for a deficit of both active elevation and external rotation. Results of 15 cases with a minimum of 2-year follow-up. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99(2):131–137. | ||

Varvitsiotis D, Dimitrios V, Papaspiliopoulos A, Athanasios P, Eleni A, et al. Results of reconstruction of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears using a fascia lata allograft. Indian J Orthop. 2015;49(3):304–311. | ||

Pandey R, Tafazal S, Shyamsundar S, Modi A, Singh HP. Outcome of partial repair of massive rotator cuff tears with and without human tissue allograft bridging repair. Shoulder Elbow. 2017;9(1):23–30. | ||

Mori D, Funakoshi N, Yamashita F, Wakabayashi T. Effect of Fatty degeneration of the infraspinatus on the efficacy of arthroscopic patch autograft procedure for large to massive rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(5):1108–1117. | ||

Mihara S, Fujita T, Ono T, Inoue H, Kisimoto T. Rotator cuff repair using an original iliotibial ligament with a bone block patch: preliminary results with a 24-month follow-up period. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(7):1155–1162. | ||

Schwartz E, Warren RF, O’Brien SJ, Fronek J. Posterior shoulder instability. Orthop Clin North Am. 1987;18:409–419. | ||

Mihata T, Watanabe C, Fukunishi K, Tsujimura T, Ohue M, Kinoshita M. Clinical outcomes after arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tear. Shoulder Joint. 2010;34:451–453. | ||

Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):459–470. | ||

Wall KC, Toth AP, Garrigues GE. How to use a graft in irreparable rotator cuff tears: a literature review update of interposition and superior capsule reconstruction techniques. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2018;11(1):122–130. | ||

Chillemi C, Mantovani M, Gigante A. Superior capsular reconstruction of the shoulder: the ABC (Arthroscopic Biceps Chillemi) technique. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2018;28(6):1215–1223. | ||

70Petrillo S, Longo UG, Papalia R, Denaro V. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for massive irreparable rotator cuff tears and cuff tear arthropathy: a systematic review. Musculoskelet Surg. 2017;101:105–112. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.