Back to Journals » ClinicoEconomics and Outcomes Research » Volume 12

Investigation of Moral Hazard Deportments in Community-Based Health Insurance in Guto Gida District, Western Ethiopia: A Qualitative Study

Authors Ayana ID

Received 16 October 2020

Accepted for publication 1 December 2020

Published 11 December 2020 Volume 2020:12 Pages 733—746

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S269561

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Giorgio Colombo

Isubalew Daba Ayana

Department of Economics, Wollega University, Nekemte, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Isubalew Daba Ayana

Department of Economics, Wollega University, Nekemte, Ethiopia

Email [email protected]

Introduction: Ethiopia introduced CBHI in 2011 as part of the health sector finance improvement. This study was accompanied to identify moral hazard behaviors in community-based health insurance in Guto Gida District of Oromia regional state.

Methods: The qualitative study used data generated from focus group discussions and in-depth interviews. Three health service centers were purposively selected for the study. Thematic analysis was accomplished using the NVivo-12 software package as it operates better in qualitative data analysis.

Results: The study found that member’s frequent visit to health service centers, tendency to collect more drugs, sense of feeling cheated by the insurance, tendency to use their cards redundantly, giving their cards to nonmembers, and seeking for most often expensive drugs were the demand side moral hazard behaviors explored by the study. From the supply side, inflating the price of drugs, increasing the price of services, alleging for services not provided, overstating the number of customers obtained insurance package and insulting users are found as moral hazard problems.

Conclusion: The study concluded that moral hazard behavior is discouraging from both the demand and supply sides. The presence of moral hazard discourages members of CBHI and creates reluctances in the scheme officials and workers. The policy implication is that tremendous attention should be given to reducing the level of moral hazard behaviors from the sides of both users and providers.

Keywords: moral hazard deportments, CBHI, qualitative study, Guto Gida, Western Ethiopia

Introduction

Currently, health security is increasingly being recognized as an integral part of sustainable development and poverty eradication strategy in most developing countries. Within the framework of the poverty reduction strategy, more attention is now given to social risk management. Of all social risks, the risk of social health is one of the greater risks that face poor households to affect their lives and livelihoods. Social health risk also increases the vulnerability of deprived households to out of compartment health expenditure as it reduces the accessibility of health care.9,10,18

Ethiopia Piloted CBHI in 13 districts for the first time in different regional states such as Tigray, Oromia, Amhara, and Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples. As a result, CBHI has been internalized very well by the surrounding community since its introduction in January 2011. Evidence from the CSA shows that enrollment rates are highly increasing. For instance, in the pilot districts alone, currently, more than 52% of eligible households, out of the target population, have enrolled and accessed CBHI health services. In Ethiopia, the CBHI service is provided at local health centers, while there are still some users that are served at hospitals.4,5,25

CBHI primarily covers essential health service packages that include both inpatient and outpatient services. The indispensable health facilities that would be covered through out-of-pocket expenditure at the time of illness are covered by CBHI schemes. Due to CBHI’s initial success, the Ethiopian Health Insurance Agency decided to scale up CBHI to an additional 161 districts. Ethiopia has observed a renewed interest in CBHI schemes as regions and districts leverage communities to expand risk-pooling coverage to informal sectors and the rural population. In addition to this, CBHI arrangements have provided an impetus to educating the range of services offered, their quality, and the actual use of resources.19,20,24

Subsequently, in 2010, two foremost types of health insurance schemes were familiarized in Ethiopia. The first type of scheme is social health insurance. Social health insurance is still not implemented in the country. The second type is community-based health insurance (CBHI). It is rolled throughout all districts in Ethiopia. The major distinction between the two is that the former is based on the voluntary decisions of the households while the latter is not. The annual payment required from every household to be a member of CBHI is 180 Ethiopian Birr per year. However, the members’ involvement varies among the pilot districts ranging from 34.4–132 Ethiopian birr.22,23

Scholars seem to agree that the idea of moral hazard is introduced in health insurance for the first time by Arrow1,2 after he borrowed the word from industrial expression7,8 However, there is no common consensus among scholars regarding whether the moral hazard is a problem or not. For instance, moral hazard is defined as a deviation from the corrective behavior and as a failure to uphold the accepted moral qualities. On the other hand,17 stated that there was nothing unethical or immoral for an insured person under a contract agreement since the person acts as a rational individual as per economic theories. In contemporary economic theories, however, the view that advocates moral hazard as a problem is attracting more attention. Starting from the time investigation of moral hazard problems in health insurance, it remains a theme of research in health economics.

Now, tremendous attention is given to exploring the problems and challenges associated with CBHI during implementation. Therefore, different studies are conducted by different scholars in different African countries on whether the CBHI implementation is promising or not. For instance, in Cameroon, there are plenty of challenges faced during the implementation of CBHI mainly due to the high drop out of the members.3,4,22 Besides, CBHI implementation in rural Senegal is found to be promising.30 It is also found that the implementation of CBHI in Ghana is encouraging.21

In Ethiopia, the implementation of CBHI is found to be promising as it attempts to upsurge access to health care and lessening the vulnerability of peoples to out-of-pocket health expenditure.11,24 After the implementation of CBHI in Ethiopia several studies are carried out to look at various aspects of CBHI. For example, factors affecting enrollment of CBHI in Ethiopia are studied by.27,28 Besides, CBHI and compliance requirement is investigated by.26 The linkage between utilization of CBHI services and the Welfare of the society is studied by.22 Moreover,6,12,13 investigated the determinants of CBHI in Ethiopia. This indicates that the existing studies in Ethiopia till today are focusing on the determinant of CBHI, the effect of CBHI, and compliance requirements on community-based health insurance. It also shows that existing studies up to now on CBHI forgot the issues of both users’ and providers’ moral hazard behaviors.

Currently, however, other dimensions of CBHI including moral hazard behaviors are attracting the attention of scholars. For instance,14,15 studied moral hazard and spending on health insurance.11,16 studied ex-post and ex-ante moral hazard in community-based health insurance. Moreover,29 investigated the evolution of the concept of moral hazard in health indemnity. This shows that the linkage between moral hazard and community-based insurance needs more investigation in Ethiopia.

However, the moral hazard comportment is very imperative in CBHI as client moral hazard is appearing in health insurance primarily when the individual does not make payment at the time of pursuing CBHI services. On the other hand, the supply side moral hazard appears in the absence of some pecuniary contemplation during service delivery.14,15

Despite several studies that enlarged understanding of the influence of CBHI and its linkage with other economic variables, various issues of community-based health insurance especially moral hazard behaviors in CBHI remain unclear. Moreover, the behaviors related to the demand side of community-based health insurance and the supply side related behaviors of community-based health insurance are not thoroughly studied in Ethiopia. Additionally, the comportments of CBHI users and CBHI service suppliers have not been adequately documented.

In addition to this, as far as my knowledge is concerned, there is no study accompanied on moral hazard compartments of CBHI in the Guto Gida District. This study, therefore, has the major aim of exploring the moral hazard behaviors in CBHI in the Guto Gida District, Oromia regional state.

Objectives of the Study

The general objectives of this study are to examine the moral hazard compartments in CBHI in the Guto Gida district.

More specifically,

- To identify client moral hazard compartments in the Guto Gida district.

- To examine Service providers’ moral hazard compartments in the Guto Gida district.

- To explore the level of the pervasiveness of moral hazard deportments in the Guto Gida District.

- To explore the ways of curing the illness of moral hazard deportments in the study area.

Scope and Limitations of the Study

This study covered only the Guto Gida district, of the 18 woreda’s in East Wollega Zone of Oromia, Western Ethiopia. Furthermore, the contemporary investigation only explored. It does not compute and calculate the magnitude of moral hazard compartments in CBHI provision as per its dispassionate. Because of this the finding of the study may be limited.

Conceptual Frame Work of the Study

The conceptual framework of the study (Figure 1 below) is framed depending on the interaction of the service providers and service users in the CBHI structure of the district. Figure 1 below shows the conceptual framework of the study. There are two parties in the CBHI structure of the district. These are service providers and users at the district level. Service providers and service users interact during service provision. The principles of service provision and service use are upon the contractual agreement between the two parties. However, both parties intentionally seek an advantage under the shadow of the contract. They seek additional advantage that is forbidden according to their contractual agreement. The two parties do not break the contract. Rather they want to stay in it but illegally. This leads to their intentional hidden action. The hidden action from the side of CBHI users reflects clients’ moral hazard compartments while it is dubbed as providers’ moral hazard compartments.

|

Figure 1 Theoretical framework of the study. |

Moreover, the users’ moral hazard is expected to be created when they go to health facilities to get CBHI service while the providers’ moral hazard is expected to be created when the health facilities provide services for the users. The moral hazard behaviors that can be reflected in community-based health insurance defined as follows.

The supplier’s moral hazard compartment occurs when additional CBHI facilities are delivered in favor of health facilities outside the idea of the contract. This type of moral hazard is called supplier moral hazard phenomena. The problem is reflected by service providers.

Consumers’ moral hazard refers to the problem that happens when peoples are enclosed by CBHI demand more care compared to the uninsured people because the cost of the superficial provision is lower than the actual cost of the service. This is called users’/clients’ moral hazard problem.

The other moral hazard behavior reflected from both demand and supply side are hidden actions that have the following forms: These are:

- Ex-ante moral hazard: the ex-ante moral hazard (reduction in disease preventive behaviors of CBHI users) refers to indications that the health of CBHI members in the forthcoming is indeterminate as it is dependent on an event.

- Ex-post moral hazard: an ex-post moral hazard (no incentive to save service provided by CBHI) is defined in this study as a hazard that happened when CBHI members are hostile.

- A hazard of hidden information: a hazard of hidden information in this study emanates from unseen evidence that is the CBHI member who cannot measure the actual loss since of the CBHI facility and thus does not pay the obligatory costs.

- A hazard of covert actions: a hazard of covert actions (invisibility of precautionary measures of individual members in CBHI) is the case in which CBHI members do not exercise the precautionary practices for themselves.

Methods of the Study

Description of the Study Area

Situated 331 km west of Addis Ababa, Guto Gida is one of the districts in western Oromia. Guto Gida is one of the top-ranking districts in the performance of community-based health insurance in the Zone. Also, the study area has good experience as it is one of the pioneering districts of the CBHI scheme in East Wollega Zone. The district has a total population of 116,045, And 16,341 household members of CBHI of which 1473 are the poorest of the poor households that are getting an incentive from the CBHI agency. This shows that 31% of the members of CBHI in East Wollega Zone are found in this district. It follows that the district encompasses more users of CBHI compared to other districts in the East Wollega Zone. The selection of the study area is logical because the district consists of more potential users and better potential suppliers of the CBHI scheme in the zone. Besides, the pioneering experience of the district in the East wollega zone is also another reason that justifies the selection of the study area.31

Guto Gida District has 21 villages (kebeles) and providing CBHI scheme services in all of the villages. Fortunately, the district surrounds Nekemte City and is providing the majority of CBHI services in the health facilities of Nekemte City administration. Currently, the district is providing community-based health insurance services in three health centers (one in Nekemte City), 21 health extension service centers, and two hospitals (East Wollega Zone Health Office,2020). Figure 2 displays the location map of Guto Gida district, the study area. The map on the right bottom side of Figure 2. Shows Ethiopia and Oromia Regional state while the map on the top right side shows the east wollega zone and respective districts.

|

Figure 2 Location map of Guto Gida district, the study area. |

Design of the Study and Data Collection Procedures

A qualitative study is carried out to explore users’ and providers’ moral hazard in Guto Gida District. The study area, Guto Gida, is selected due to its better experience and performance in the CBHI system service provision. Moreover, Guto Gida is among the best-ranked districts in East Wollega by CBHI. Moreover, it is to obtain all the necessary evidence from all concerned bodies. Further, the study also deals with the prevalence of moral hazard in health insurance.

Qualitative data is collected through In-depth interviews and Focus group discussions. The qualitative information is collected in two ways. First, FGD is conducted in Nekemte referral Hospital, Wollega University Referral Hospital, and Nekemte Health Center.

The hospitals and health centers are currently giving CBHI services in the district. The FGDs are two places in a district with Centers CBHI officials and district CBHI Officials. Groups are composed of six to 10 participants. This composition of the group includes CBHI officials; male-headed and female-headed household members, hospital officials, doctors, nurses, and hospital support staff. Participants were randomly selected into a group.

Six to 10 accomplices are favored to obtain meaningful data from the participants of the study. On the other hand, if contributors are fewer than this it is very challenging to obtain the desired level of data. It is also very useful to diminish the domination of the conversation by fewer peoples. To prevent this problem the members of the focus group discussion increased. All the FGD participants should be users and providers of the CBHI scheme. The discussions will be focused on the moral hazard behaviors that are reflected by users and service providers of the CBHI scheme.

Focus group discussion was conducted with the required procedures to achieve the goals of the study. The FGD was carried out with peoples of mutual concentration. The list of CBHI beneficiaries was obtained from the district CBHI office. It is after this that the members were selected for FDG. A random draw of participants was conducted from this. The focus group discussion included male and female beneficiaries of CBHI.

During the selection of FDGs core principles were applied. Discussions were conducted separately with members of CBHI and officials of CBHI. Therefore, differences in the community were considered in deciding which groups of peoples to select. FGDs were also held with participants from members and officials of CBHI.

In the second round, an In-depth interview was held with CBHI officials for executing the program. This was held at the district and Village (Hospital and Health Center) levels. The IDI participants were also asked to forward a suggestion on the moral hazard behaviors that are reflected by users and service providers of the CBHI.

Data was collected in Afan Oromo, and translated into the English language by the investigator. Appropriate data quality control activities were carried out. Since the investigator can speak the local language, he acted as conversant in the local languages for data collection. Data were collected between February 2020 and March 2020. To achieve the objective of the study, four FGD and four IDI were accompanied by various groupings of people in the selected hospitals and health facilities.

Recording Data from FGDs and In-Depth Interviews

During the study, FGD and in-depth interviews were documented by taking comprehensive field notes by mobile phone cameras. Results from the FGD and in-depth interviews for use in the investigation were included in notes of the discussions. The researcher noted down the discussion among the contestants as they speak, using the words they used. Besides, the investigator was also noting occasions when participants disagree on the ideas and concepts of the focus group discussion. Moreover, direct quotations were recorded where they illustrate an important point. The work of changing the main records of discussions and in-depth interviews were done by the investigators.

Sampling Techniques of the Study

Qualitative study most of the time uses non-probability sampling. The present study, therefore, used purposive sampling that seeks conceptual applicability instead of quantitative representativeness. This method of sampling is preferred over others as it seeks to capture the range of opinions, experiences, pursue saturation of data.

In Guto Gida District, the CBHI service is under operation in six kebeles. Currently, four health centers and two hospitals are giving CBHI services in the study area. Since Guto Gida is surrounding Nekemte city, the largest service of CBHI in the district is given in Nekemte City. The focus of the study was the CBHI services in Nekemte city on the behalf of Guto Gida District.

Two hospitals and one health center were selected for the study. The two hospitals are; Nekemte Referral Hospital and Wollega University Referral Hospital while Bake Jama Health Center is the health center that is selected in the study. The hospitals and health centers are currently delivering the CBHI service on the behalf of district CBHI office as per the agreement between the district and these health facilities. Consequently, these three health facilities (two hospitals and one health Center) were purposively selected for the study.

Ethical Considerations of the Study

Currently, ethical considerations are considered as, not only the issue of ethics but also the part of the method of the study, especially in qualitative researches. Therefore, this section outlines general guidelines and conduct FGDs and IDIs. It also sets out some overall standards of behavior employed in a study area. Though it is obvious, it is very important to ensure that our research is both accurate and ethical. To ensure successful data collection, ethical clearance was obtained from the Department of Economics, Wollega University, together with a permission letter approved by Guto Gida Woreda CBHI office consisting of objectives of the study.

Conduct of CBHI Members, CBHI Officials, and Investigator

During the study, members of the CBHI and CBHI officials were clear about their roles. They will be also highly motivated to seek fully informed consent. They were also encouraged to answer questions openly. Moreover, the researcher assumed that the participant’s response during the study was highly confidential. Therefore, members of CBHI and CBHI officials were not felt demeaned or offended by anything the investigator did, said, or asked about or by investigators’ behavior in hospitals or health centers during the study.

The researcher is in their community and respects respondents and the community in general in line with their culture. The investigator will communicate with the respondents so that the expectations of community members and research participants must not be raised by anything the investigator do or say during the research. Therefore, they understood that this study is just for academic purposes.

In addition to this, Potential respondents understand that no explicit or implicit pressure to participate in the study either from the researcher or from CBHI officials or any other bodies due to the participation in this study. Finally, participants were well informed that the study is more accurate if participants see no reason to adjust their responses in a particular way. Therefore, respondents understand that the study is more precise if they feel comfortable during the FDG and IDI.

Ethical Considerations During FGD and IDI

The investigator ensured that authorization is pursued by the focus groups to go forward. Clear parameters for the focus group were communicated for the focus group. The researcher communicated that the maximum time for the FDG is one to two hours. The awareness was also given to the discussants that they have the right to withdraw at any time from the FGD. The idea that the researcher is independent of implementing agents such as hospitals and health centers was also communicated with the participants of the study.

Moreover, FGD was set at the time and in spaces that are suitable to respondents. The fact that relates to this is that the safety and protection of participants were ensured. The environment in which FDG was carried out was physically safe and the researcher acted as a facilitator. Another ethical consideration focused is the FDG language. FGD was conducted by Afan Oromo to ensure that people apprehend what is happening at all periods throughout the study. It is checkered that all contestants speak Afan Oromo as their mother tongue.

During the focus group discussion, the right to privacy was given to respondents. These rights include ensuring inconspicuousness and concealment, in record-keeping and report-writing. It was also clear that the flow of questions was bidirectional as respondents were encouraged to equally ask questions.

The main things that were kept in mind during FGD and IDI were: The researcher introduced himself to the discussants. The subject and objectives of the discussion were introduced. It was checked that the contestants sense comfortable with what is going to be discussed. This was very important to create a common understanding of the objectives of the study between the respondents and investigators. Thematic analysis is accomplished using the NVivo-12 software package for final analysis. This software package, NVivo-12, is preferred over the others since it performs better in the analysis of qualitative data.

Results and Discussions

The section comprises the results obtained from FGD and IDI and also discussions about it. It also constitutes moral hazard behaviors that are reflected by users and suppliers.

Demand Side Moral Hazard Deportments in Guto Gida District

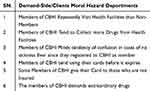

The qualitative study was accompanied with the specific objective of scrutinizing the moral hazard behaviors of CBHI members in the study area, Guto Gida. From the data obtained through focus group discussion and in-depth interviews, six different moral hazard behaviors were reflected by CBHI members of the district as depicted in Table 1 below.

|

Table 1 Demand-Side Moral Hazard Deportments in the CBHI Scheme |

The moral hazard deportments from the client side in Table 1 above are explained below one by one. These are:

Members of CBHI Repeatedly Visit Health Facilities Than Non- Members

In the Guto Gida district, the members of CBHI are more likely to visit the health insurance service provision areas (Nekemte specialized hospital, Nekemte referral hospital, and Nekemte health center) than noninsured peoples. This is because they want to take some advantage under the shadow of their membership to CBHI. The data also depicted that members of CBHI regularly visit not only the service provider they are assigned to but also other areas to swindler the service providers in the district, Guto Gida. This shows that there are members of CBHI in the study area that act as a double-dealer, reflecting the dangerous conduct of the members. This does not mean that the users break the contractual agreement. It rather shows that they want to stay under the shadow of the contract. This is due to the high cost of membership card renewal.

One of the contestants in the focus group discussion used her word to spindles that:

The members of CBHI in Guto Gida sense no comfort if they fail to regularly visit Hospitals and health centers in the study area (Focus Group Discussion, Female).

This statement of the female respondent divulges that the members of CBHI commonly visit the insurance service provision areas just to acquire some benefit under the cover of the insurance membership. This displays that the demand for moral hazard (CBHI user’s hazardous behavior) is observable in the Guto Gida district community-based health insurance.

Members of CBHI Tend to Collect More Drugs from Health Facilities

The data from the focus group discussion illustrates that the members of CBHI have shown the tendency to collect more drugs from the health facilities using their membership reflecting the manifestation of demand-side moral hazard comportment in community-based health insurance in the study area. It is detected also that the members of CBHI go to another health facility to collect more drugs after collecting drugs from other facilities. The members complain about the same drug and collect it again. The study participants responded in their words as:

Members of community-based health insurance come to the CBHI service provision areas just after putting collected drugs in their home. The CBHI members do not even use the drugs as per the order of the doctor as they quickly back to the health facilities to collect additional drugs from the insurance service providers. The respondent added that there is a time in which they come back to health facilities within two or three days. Even the health officers have detected that some immediately go to another facility after they have collected the drugs through identical sickness and gather more additional tablets again and again (Pharmacist, Female).

Members of CBHI Minds Tendency of Confusion in Cases of No Sickness Ever Since They Registered to CBHI as Member

Depending on the data collected from the focus group discussion in the study area, members of the CBHI inclines to be confused when there is no illness meanwhile their registration as a member of the health insurance. This shows that the members of the health insurance have a sentiment that they ought to go to community-based health insurance provision centers to collect more drugs even if there is no case of sickness among the family members. One focus group discussant explained that:

Members of CBHI replicate the tendency of misperception in case of no sickness since their accomplishment of the health insurance scheme membership process. It is due to this circumstance that the members of CBHI should just wrinkle more and more drugs from the provision hubs (Focus group discussion, Male).

Members of CBHI Tend Using Their Cards Before It Expires

From the study conducted in the Guto Gida district, it has been shown that the members of CBHI in the Guto Gida district worry about the date of the expiry of their membership card. In addition to this, the CBHI members know that their card expires at the end of the fiscal year of Ethiopia. Their card starts on July 1 and ends on June 30 of Ethiopia. As they are apprehensive about the cost of renewal of the card of the insurance, the members of CBHI avail to the centers to use their cards beforehand it expires. This shows that the cost of renewal of the CBHI membership card is very high compared to the income of the users of the health amenity. In addition to this, participants also identified that attendances are high around every year when the card of members is to be expired. Thus, hospitals and health centers are full because some peoples will like to use their cards and collect drugs before it expires.

One partaker of the in-depth interview identified in his word:

At the end of June CBHI, membership cards will need to be renewed. Due to this the CBHI service provision centers are typically much occupied and the presences of the insurance service seekers increase. This is just for the fact that certain CBHI members would like to consume their membership insurance identification passbooks before it expires (District CBHI officer, Female).

Some Members of CBHI Give Their Card to Those Who are Not Insured

The study also identified another moral hazard behavior by users. Focus group participants admitted that numerous members of CBHI are going to service provision centers (Nekemte Specialized hospital, Nekemte referral hospital, and Nekemte Health centers) just to collect drugs for nonmembers of CBHI. It is also indicated by participants that some nonmembers go to the CBHI service delivery sectors by capturing their kin’s indications of a bug in mind to gate advantage of their CBHI cards. This is a somber particular area where authorities are not care full in their work according to the participants of the study.

One of the participants of the focus group discussion disclosed in words that:

Members of community-based health insurance usually deliver their CBHI cards to nonmembers to enable them to collect the drug from the CBHI service provision centers. This enables their relatives to be benefited from the CBHI even if he or she is not a member of CBHI in the Guto Gida district. For me, the participant said, the CBHI officers and CBHI service provision centers must be blamed here. This act can be avoided by differentiating the color of the cards, and attaching a clear photo of the CBHI members on their membership cards (Focus group discussion, female).

The Members of CBHI Demands Extraordinary Drugs (Commonly Requests Particularly the Most Affluent Medicines for Prescription)

From the focus group discussion steered, it is found that members of CBHI claim the extraordinary drugs under the shadow of the CBHI structure. When they go to insurance service providers in the district, they often call very exclusive and expensive drugs from the service suppliers. The partakers affirmed also that some users of CBHI impulse the CBHI service provision center workers to commend very classy type of drugs. This confirms that the CBHI scheme in Guto Gida district is reflecting plentiful moral hazard deportments which adversely shake the CBHI insurance pattern in Guto Gida.

One of the participants in the study contested in words that:

Innumerable members of CBHI users come to CBHI service running centers to enquire about you to prescribe an expensive drug for them. Usually, they demand that doctors in the CBHI service provision centers need to just quickly prescribe it for them to collect it from the center’s drug stores. When CBHI service delivery centers inform them that there is no that particular drug here, they think that it is because they have no friend here or dishonesty of medical workers in CBHI service provision centers (Medical doctor, Female).

Moral Hazard Deportments by Service Providers

The second particular objective of this study is to pinpoint the moral hazard comportment that is reflected by the service providers. Accordingly, FGD participants explained numerous deportments by the facility suppliers that institute it. This precise study identified four different suppliers’ moral hazard deportments in Guto Gida District as depicted in Table 2 below.

|

Table 2 Supply-Side/Service Providers Moral Hazard Deportments |

Four of the suppliers’ side moral hazards are noticeably elucidated below.

Overestimating the Cost of Service Delivered to Customers of CBHI

Moral hazard behavior observed from the angle of the service provider goes to the cost of drugs and services. An in-depth interview conducted shows that service providers overcharge the drugs and other services that are given to the members of CBHI.

The participants of the in-depth interview believed in his word:

In CBHI service provision centers the executives overstate the cost of service supplied to the customers of the insurance arrangement. For instance, they increase the number of appointments to the CBHI provision centers. If a certain customer visits the centers once a week the workers of the centers report it like twice a visit per week. In addition to this, the CBHI service center provision workers may also overstate the cost of drugs (CBHI officer, Male).

CBHI Service Suppliers Occasionally Charge for Undelivered Insurance Services

It is explored also that service providers sometimes charge for the services that are not provided for the members of the CBHI. To be more specific, several CBHI service center workers report variously cased of not provided services.

One of the contenders in the study supposed in own words that there is a case of reporting not delivered service as:

If the visit was to headache they may report it as the case of malaria. Moreover, the CBHI center workers may also report the increased number of clients visiting the center per day. If for example, ten customers visit the CBHI service provision centers per day it may be reported as fifteen peoples visiting the centers (CBHI officer, Female).

Puff Up the Cost of the Insurance Services for CBHI Clients Only

This is a series of the problem under which the CBHI officials and CBHI service provision centers collude to abuse the CBHI system. This type of supplier’s moral hazard comportment can seriously be distressing the future of the CBHI program in the district, the study area.

An in-depth interview carried out with the higher general officer of the CBHI exposed that:

The CBHI service provision centers and some CBHI center officials some time create collusion to just cheat the program. I can say there is a sort of corrupting the CBHI program in the district and hidden but the visible cheating agreement between district CBHI officials and CBHI service provision centers (Health centers and Hospitals in Nekemte) (CBHI Official, Male).

Some Health Officers (Nurses) Insult the Members of CBHI

The participants of FGD explained that some health facility officers or nurses sometimes insult members of CBHI if they fail to go to the health facility very early. Even when CBHI waits until the medication works, their situation may be worsened. However, nurses force the members of CBHI to go immediately for treatment.

One contributor of the in-focus group discussion contested in owns words that:

There are CBHI service provision center workers (nurses and medical doctors) that on occasion offense (insult) the CBHI users for the regular visit to the service provision centers. The participant of the focus group discussion even alleged that there is even a sound of insult from the workers for the delay of the CBHI service consumers in going to the centers. I think this is a common misbehaving activity for them. In addition to this, they also sometimes insult as if the CBHI customers are accumulating the drugs from the centers just for the sec of the membership not because they worth the medication at the time. The contributor also added that the providers of the CBHI program should wait a time and give the turn to non-users of the CBHI. It follows that they give a turn for the cash payers instead of CBHI cardholders (Focus group Discussion, Male).

Public’s Level of Awareness on Moral Hazard Deportments

The study steered reflected that the public’s level of awareness on the effect of the moral hazard compartment is very high. From both users and providers of the CBHI service, it is well digested that the hazardous behavior of CBHI insurance is a huge threat to the sustainability of the program. Furthermore, it deleteriously affects the program from the angle of both demanders and suppliers of the service. This type of illegally seeking advantage from the insurance system has also the huge capacity of disheartening the nonmembers and members of the CBHI. This act also depresses the nurses and medical doctors in the CBHI service provision centers. This leads to less contribution to the CBHI scheme and more utilization of it. Finally, it puts the sustainability of the scheme into question through overexploitation of the scheme from both users and service providers.

One of the participants contested during the focus group discussion:

The moral hazard compartment I am observing now in the program will lead the program to a colossal liability level and in turn to the collapse of the CBHI scheme. There is an observable act of cheating the CBHI program from both users and providers of the program. I meditate that the program is surviving for the reason that the government subsidizes it. I do not think the program will survive without government maintenance. If this cheating of the program stopover, I anticipate the program will benefit both users and providers (Focus Group Discussion, Female).

Solutions to Reduce Moral Hazard Evils

One of the specific objectives of this study was the curative ways of moral hazard compartments. The participants forwarded solutions for both provider’s and user’s moral hazard behaviors. The solution ideas forwarded by respondents are explained in Table 3 below.

|

Table 3 Solutions to Minimize Moral Hazard Deportments in the CBHI Scheme |

The solutions to minimize moral hazard deportments listed in Table 3 above are enlightened below.

Reduction of the Registration and Renewal Fees

The study accompanied replicated that members of CBHI give their cards to other noninsured peoples due to the high cost of registration and renewal fees. Thus, reductions in registration and renewal fees in CBHI are the solutions to reduce the moral hazard actions.

One of the accomplices supposed in own words that:

High registration and renewal cost are among the major reasons that force peoples not to be members of CBHI. I think the government needs to reassess the cost of renewal and the cost of registration for the CBHI program. For me, the act of misusing the CBHI program will theatrically decrease if the government reduces the cost of renewal and registration (Focus group discussion, Male).

Premium Should Be Paid by Installment

Another moral hazard problem identified in the CBHI arrangement in Guto Gida is that the payment is not on the base of the installment. Rather the payment is to be paid only at a time. According to the data obtained from the participants of the study, the CBHI program needs to install the time of payment on the ordered basis that may be monthly or yearly.

One of the participants of the study alleged in own words that:

If there is a promising way to pay the membership cost slowly but surely on the installed time bases, I think I will not be in crisis during the new registration and renewal of the CBHI membership cards. Thus, as for me, the payment needs to be on an installed basis weekly or monthly. This is to reduce large payment that waits for the members at the time of renewal of the CBHI card (Focus Group Discussion, Male).

Health Workers Should Be Careful Before Attending to the Patient

The attention of health workers is highly crucial to identify the name and picture of CBHI users. Thus, attending patients should be after the users and service demanders are identified.

One of the participants of the study alleged in own words that:

The CBHI service provision center workers should look at the picture of the CBHI card to identify who is getting the service. If this happens the users of the CBHI will not provide their cards to nonmembers. Additionally, the picture on the card should be noticeable as much as possible. This can be checked during registration by Guto Gida CBHI officers. Moreover, the color of the card ought to also differ across the kebeles. This will also reduce the numbers of CBHI users swapping their cards across the villages (Focus group discussion, Male).

Plummeting the Nonessential Visits to CBHI Service Provision Centers

The study conducted explained that service demanders should reduce the number of non-essential visits to centers of CBHI. This reduces the number of CBHI users that go seeking the advantage under the shadow of the CBHI insurance service. The participants of the study suggested also that this diminishes the exploitation of the insurance program. Consequently, CBHI members should reduce unnecessary visits as it is good for them. The government should also put an upper limit on the number of visits. This is very important for the sustainability of the CBHI program.

One of the participants of the study alleged in own words that:

I think there should be an unvarying arrangement on the time of CBHI members’ visits to the service delivery centers. Unless it is for emergency cases, the time of the visit to health centers should be compacted. This helps the providers to think over the eminence of the CBHI service. This enables them to work for the advancement of the CBHI program. It also supports the users of CBHI to erode misperception on the service quality of the CBHI program.

Awareness Creation for Users and Service Providers

The study conducted by the use of focus group discussion and in-depth interview suggested a solution that favors awareness creation for both users and service providers. Officials of CBHI believed that awareness creation is one of the powerful tools to change moral hazard problems in CBHI service provision areas.

One of the contestants in the study said:

As far as service providers are concerned, the moral hazard problem can be altered by educating both CBHI users and providers in the district. For me, this is a very important way of reducing hazardous problems sustainably. Peoples seek illegal advantages from the CBHI under the cover of the insurance due to the lack of information regarding the advantages (CBHI Official, Male).

The result and discussion part of this study can be summarized in Table 4 below.

|

Table 4 Summary of the Results and Discussions |

Conclusion and Policy Implication

Conclusion

This study explored the moral hazard comportment in CBHI in Guto Gida District, Oromia, Ethiopia. A qualitative study is accompanied by FGD and IDI. Using thematic analysis, it is found that there are two side moral hazard behaviors in community-based health insurance in the study area.

First, the moral hazard comportment is revealed in the demand side when CBHI clients get compensations for the scheme without payment. Second, the moral hazard comportment is replicated on the supply side as the suppliers need to take benefit of the CBHI scheme.

The study concluded that moral hazard deportments observed from the users of CBHI side are repeated visits of health conveniences, tendency to gather more drugs from health facilities, sense of feeling cheated if no illness after having CBHI cards, tendency to use their cards before it expires, giving their card to uninsured and asking for specific drugs to be suggested for them.

Besides, the moral hazard comportments from the provider’s side are overcharging for undelivered services to customers, overestimating services supplied, swelling the number of clients who obtained services within a given time, and impertinent users.

Moreover, the study concluded that the level of prevalence of both moral hazard behaviors (users and providers) is very high in the study area. It is indicated that such behaviors make health workers reluctant to indulgence insured people and disappoint sick peoples with CBHI cards from going to the health facility. It is also indicated that such behaviors could lead to the downfall of the scheme.

Finally, the study established that the advised ways of reducing moral hazard comportment are tumbling unnecessary visits by CBHI members, constructing awareness for users and service providers, and providing training on the significant drugs for providers and users.

Policy Implication

As the central objective of the study was to explore moral hazard deportments in community-based health insurance, the policy directions were indicated depending on the conclusions.

Therefore, it is implied to the policy that the suitable roads to condense repeated unnecessary visits of CBHI to health amenities would be conventional. Moreover, a way of having a compact inclination of collecting more drugs from health facilities needs to be concocted by the providers. It is also very imperative to form the minds of users of the CBHI scheme through pieces of training and awareness creation approaches.

Additionally, both users and providers need to be assured that collecting more drugs in advance has no enticement in the government policy of CBHI.

Above all, card usage and card renewal systems should be thoroughly controlled by providers and concerned bodies as a means of reducing the tendency of using cards before it expires and giving cards to not insured persons.

From the provider’s side, incomes of controlling overpricing of drugs and overestimating of services provided for CBHI members should be well established. The payment systems need to be a copayment to alleviate moral hazard deportments.

Another policy implication is that registration of the members who obtained services per a given time should be registered in the check and balance system as the providers sometimes cheat the scheme by inflating the number of CBHI card owners acquired services in the health facilities.

The behaviors of the CBHI service providers should discourage CBHI cardholders. A strong follow-up mechanism should be established in the health providers as some health officers and nurses show rudeness to CBHI members. Finally, unless attention is given to reducing the moral hazard deportments in the CBHI scheme, its sustainability is questionable.

Abbreviations

CBHI, community based health Insurance; CSA, Central Statistical Agency-Ethiopia; FDG, focus group discussions, FDMOH, Federal Ministry of Health–Ethiopia; IDI, in-depth Interview; WHO, World Health Organization.

Ethics and Consent Statement

Informed consent to take part in the study was received from the participants including publication of their anonymized responses. This study was also conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgment

I would also like to express my sincere gratitude and appreciation to Melkamu Wolde and Firdissa Sadeta for their critic and valuable contribution to this work. Frankly speaking, this paper may not be as smart as it is without the unreserved follow up and supervision by those excellences.

Disclosure

The author reports no conflict of interest in any form or shape. The author has decided to work on this article to contribute to the body of knowledge in health economics and business sciences. Thus, this article is purely a scholarly work for advancement academics.

References

1. Abbring JH, Chiappori P-A, Zavadil T. Better safe than sorry? Ex-ante and ex-post moral hazard in dynamic insurance data. SSRN Electron J. 2008. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1260168

2. Arrow KJ. Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. Am Econ Rev. 1963;53(5):941–973.

3. Barros PP, Machado MP, Sanz-de-Galdeano A. Moral hazard and the demand for health services: a matching estimator approach. J Health Econ. 2008;27(4):1006–1025. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.02.007

4. Bennett S. The role of community-based health insurance within the health care financing system: a framework for analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19(3):147–158. doi:10.1093/heapol/czh018

5. CSA. Central statistical agency of Ethiopia. Knoema.com. Available from: https://knoema.com/atlas/sources/Central-Statistical-Agency-of-Ethiopia.

6. Yohannes A A proclamation to provide for social health insurance (proclamation no. 690/2010) - Ethiopian legal brief. Chilot.me. January 20, 2011. Available from: https://chilot.me/2011/01/a-proclamation-to-provide-for-social-health-insurance-proclamation-no-6902010/.

7. Yohannes A The federal negarit gazeta - Ethiopian legal brief. Chilot.me. November 1 2011. Available from: https://chilot.me/2011/11/the-federal-negarit-gazeta/.

8. Finkelstein A. The aggregate effects of health insurance: evidence from the introduction of medicare. Q J Econ. 2007;122(1):1–37. doi:10.1162/qjec.122.1.1

9. Federal democratic republic of Ethiopia ministry of health: health sector development program IV 2010/11–2014/15. Healthynewbornnetwork.org. March 2, 2016. Available from: https://www.healthynewbornnetwork.org/resource/federal-democratic-republic-ethiopia-ministry-health-health-sector-development-program-iv-201011-201415/.

10. Be Healthy to Learn, Learn to be Healthy. School health program framework. Corhaethiopia.org. Available from: https://corhaethiopia.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Final-School-Health-Program-Framework-August-2017_FINAL.pdf.

11. Workneh SG, Biks GA, Woreta SA. Community-based health insurance and communities’ scheme requirement compliance in Thehuldere district, northeast Ethiopia: cross-sectional community-based study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;9:353–359. doi:10.2147/CEOR.S136508

12. Jembere MY. Community based health insurance scheme as a new healthcare financing approach in rural Ethiopia: role on access, use and quality of healthcare services, the case of tehuledere district, south Wollo zone, northeast Ethiopia. Fam Med Med Sci Res. 2018;07(02):1–6. doi:10.4172/2327-4972.1000227

13. Haileselassie H Socioeconomic determinants of community-based health insurance the case of kilte awelaelo district, Tigray regional state; 2014.

14. Einav L, Finkelstein A, Ryan SP, Schrimpf P, Cullen MR. Selection on moral hazard in health insurance. Am Econ Rev. 2013;103(1):178–219. doi:10.1257/aer.103.1.178

15. Leive A, Xu K. Coping with out-of-pocket health payments: empirical evidence from 15 African countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(11):849–856. doi:10.2471/BLT.07.049403

16. Minyihun A, Gebregziabher MG, Gelaw YA. Willingness to pay for community-based health insurance and associated factors among rural households of Bugna District, Northeast Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):55. doi:10.1186/s13104-019-4091-9

17. Pauly MV. The economics of moral hazard: comment. Am Econ Rev. 1968;58(3):531–537.

18. WHO. Community-based health insurance schemes in developing countries: facts, problems and perspectives; 2015. Available from: https://www.who.int/health_financing/documents/cov-dp_03_1_community-based/en/.

19. WHO. State of Health Financing in the African Region. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Africa; 2013.

20. Sambo LG, Kirigia JM, Orem JN. Health financing in the African Region: 2000–2009 data analysis. Int Arch Med. 2013;6(1):10. doi:10.1186/1755-7682-6-10

21. Yawson AE, Biritwum RB, Nimo PK. Effects of consumer and provider moral hazard at a municipal hospital out-patient department on Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme. Ghana Med J. 2012;46(4):200–210.

22. Yilma Z, Mebratie A, Sparrow R, Dekker M, Alemu G, Bedi AS. Impact of Ethiopia’s community based health insurance on household economic welfare. World Bank Econ Rev. 2015;29(suppl 1):S164–S173. doi:10.1093/wber/lhv009

23. Shigute Z, Mebratie AD, Sparrow R, Yilma Z, Alemu G, Bedi AS. Uptake of health insurance and the productive safety net program in rural Ethiopia. Soc Sci Med. 2017;176(9833):133–141. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.035

24. FMOH. The Ethiopian health sector transformation plan II. Gov. et. Available from: http://www.moh.gov.et/ejcc/am/node/152.

25. FMOH. Ethiopia Health Sector Development Program; 2007. Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/9549.

26. Ebrahim K, Yonas F, Kaso M. Willingness of community to enroll in community-based health insurance and associated factors at household. J Public Health Epidemiol. 2019;11(6):137–144. doi:10.5897/JPHE2018.1094

27. Mebratie AD, Sparrow R, Yilma Z, Alemu G, Bedi AS. Enrollment in Ethiopia’s community-based health insurance scheme. World Dev. 2015;74:58–76. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.04.011

28. Atnafu DD, Tilahun H, Alemu YM. Community-based health insurance and healthcare service utilization, North-West, Ethiopia: a comparative, cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(8):e019613. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019613

29. Robert A, Levine TC. Moral hazard and health care- is there an answer? – the moderate voice. Themoderatevoice.com. July 30, 2012. Available from: https://themoderatevoice.com/moral-hazard-and-health-care-is-there-an-answer/.

30. Abt assists Senegal in the expansion of community-based health insurance. Abtassociates.com. Available from: https://www.abtassociates.com/who-we-are/news/feature-stories/abt-assists-senegal-in-expansion-of-community-based-health.

31. Gida DAG Demography of Guto Gida District by the district administration. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. August 12, 2020. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Guto_Gida&oldid=972446284.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2020 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.