Back to Journals » Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment » Volume 11

Interaction of social role functioning and coping in people with recent-onset attenuated psychotic symptoms: a case study of three Chinese women at clinical high risk for psychosis

Authors Zhang T , Li H, Woodberry KA, Seidman LJ, Chow A, Xiao Z, Wang J

Received 29 March 2015

Accepted for publication 6 May 2015

Published 6 July 2015 Volume 2015:11 Pages 1647—1654

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S85654

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Professor Wai Kwong Tang

TianHong Zhang,1 HuiJun Li,2,3 Kristen A Woodberry,3 Larry J Seidman,3 Annabelle Chow,4 ZePing Xiao,1 JiJun Wang1

1Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China; 2Department of Psychology, Florida A&M University, Tallahassee, FL, USA; 3Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA; 4Department of Psychological Medicine, Changi General Hospital, Singapore

Abstract: Clinical high risk of psychosis is defined as the period in which the first signs of psychotic symptoms begin to appear. During this period, there is an increased probability of developing frank psychosis. It is crucial to investigate the interaction between psychotic symptoms and the individual’s personality and life experiences in order to effectively prevent, or delay the development of psychosis. This paper presents case reports of three Chinese female subjects with attenuated positive symptoms, attending their initial outpatient assessment in a mental health service, and their longitudinal clinical outcomes. Information regarding each subject’s symptoms and life stressors was collected at 2-month intervals over a 6-month period. The assessments indicated that these women were suffering from the recent onset of symptoms in different ways. However, all three hid their symptoms from others in their school or workplace, and experienced a decline in performance related to their social roles and in their daily functioning. They were often excluded from the social groups to which they had previously belonged. A decline in social activities may be a risk factor in the development of psychosis and a mediator of functional sequelae in psychosis. Effective treatment strategies may include those that teach individuals to gain insights related to their symptoms and a service that provides a context in which individuals can discuss their psychotic symptoms.

Keywords: prodromal psychosis, ultra high risk, follow-up, functional sequelae, transition

Introduction

Although it is well known that there is a strong genetic or biological underpinning to psychosis,1 the role of social factors in the development of psychosis has perhaps been underestimated in clinical practice and research. Clinicians and scientists in the People’s Republic of China may overemphasize the question, “What has changed in the brain of a psychotic patient?”, and they do not often ask, “How do changes in the patient’s social world affect the brain and behavior of a psychotic patient?” In addition, it is difficult to explore underlying problems, such as the interaction between psychotic symptoms and the social role functioning and coping, through quantitative studies that use questionnaires or cross-sectional interviews.

A recent development in psychiatry has the potential to provide a more complete and in-depth understanding of the development of psychotic disorder. The concept of a prodromal stage of psychosis, or clinical high risk (CHR) syndrome, has evolved over the last 20 years.2–6 According to follow-up studies, the CHR transition rate within a year of the first manifestation of symptoms averages approximately 20% and increases to around 35% within 3 years.3,7–9 Thus, nearly two-thirds of those at CHR may not develop psychosis, at least within a relatively short time span. Biomarkers may ultimately help to identify individuals who are likely to progress to full psychosis, but each individual’s unique background may also contribute to outcomes other than the onset of psychotic symptoms.

We present the cases of three Chinese female subjects of different ages and backgrounds who fulfilled the criteria for attenuated positive symptom or syndrome (APSS), one of the CHR syndromes. We collected information on symptoms and life stressors every 2 months for 6 months. We examined these cases to understand the more detailed processes by which the individuals deal with APSS in their everyday lives.

Case reports

Three cases were selected from a broader research study10 of CHR in a Chinese clinical population conducted in 2012. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the Shanghai Mental Health Center. All three subjects were identified via screening with the Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief version11 and met the APSS criteria in the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes.12 Subjects returned for follow-up appointments every 2 months to discuss the development of psychosis as well as problems faced in their social lives.

Background

The subjects included one younger (15 years; Case A) and one older teenager (18 years; Case B) and a young adult (35 years; Case C), each from a typical Chinese household. The recent onset of attenuated psychotic symptoms precipitated a drastic change in their normal lives and social roles. Thus, it was with significant uncertainty and desire that these individuals sought help in a psychological-counseling setting at the Shanghai Mental Health Center (in the People’s Republic of China, this setting is associated with less stigma than psychiatric settings). They attended counseling sessions with various kinds of pressure from their families, schools, and workplaces – and from society in general. The subjects had similarly poor interpersonal skills and limited social support outside their families. Their personality traits, family situations, life experiences, and social activities were quite diverse, but none had a prior history of medication use, psychological treatment, hospitalization, serious physical problems, substance abuse (drug or alcohol), or mental disorders within the family (Table 1).

| Table 1 Background information on the CHR subjects |

Baseline attenuated psychotic symptoms

All three women experienced unusual ideas and perceptions. Each woman described her symptoms differently, in a way that was consistent with her background. For example, Case A was very fond of mystery and suspense stories, and she attributed her hallucinations to supernatural forces. Case B experienced sudden auditory hallucinations, and, consistent with her college background, tended to explain the voices in scientific ways (eg, being implanted with a mind-reading device). Case C had experienced a greater number of changes and hardships than the other subjects. One significant stressor was a recent divorce, which is still a widespread cause for discrimination in Asian societies. Her suspiciousness was primarily related to her divorce. These cases illustrate how psychotic symptoms might reflect individual experiences and environments (Table 2).

Follow-up

Although 6 months is a relatively short period in the course of a potential psychotic disorder, it is a critical period from the perspective of illness development. The women described here were struggling in their daily lives and suffering with the recent onset of symptoms in different ways. Their social role and daily functioning had declined to varying degrees. They were often excluded from the social groups to which they had previously belonged. In addition, these cases suggest that the older the person is at symptom onset, the greater the difficulties he or she may face in certain social contexts. One potential reason may be that unusual thoughts may be more acceptable in younger than older people because the young are thought to be more imaginative. Thus, society may be more tolerant of certain symptoms in teenagers than in college students or adults (Table 3).

| Table 3 Changes in CHR subjects during the 6-month assessment period |

Summary

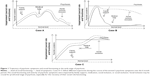

Figure 1 shows the course of the women’s psychotic symptoms over the 6-month period. Although they seem to follow different trajectories in the early stage of psychosis, it is obvious that medical help may have had some effect on their symptoms. The social functioning of Cases A and C synchronized with the severity of their symptoms. Social inclusion of subjects with recent-onset psychosis may be crucial, especially for the recovery of their social role functioning. Sadly, social exclusion was a large part of each of these women’s experiences during the initial period after symptom onset.

Discussion

We described three cases with recent-onset psychotic symptoms in individuals who appeared at first to be insightful and eager for help. Each struggled with severe pressures in their daily lives. Psychosis has attracted considerable attention in clinical settings in the People’s Republic of China; it is not surprising that all three subjects had been prescribed antipsychotic medication by our clinicians, none of whom had much experience with the concept of “CHR”. Although there is still considerable debate regarding ethical issues with the use of medication in the prodromal stage,13,14 medication in these three cases resulted in some improvements. However, the way the women balanced their real-world responsibilities and their psychotic symptoms was quite varied. Moreover, the effectiveness of and compliance with treatment did not appear to rely on a particular (or “just right”) medicine.

Insight during the early stages of psychosis has been associated with better outcomes.15,16 Yet the quality of insight should be carefully considered and nurtured.17,18 Individuals with mental illness have limited resources and capability to openly express and manage their confusion about their psychotic symptoms. In the cases presented in this paper, family members were the first resources from whom the women could seek help. After family, professional but less stigmatized institutions were their second preferred option. Services19 that help individuals interact with society are urgently needed. This reality-based interaction may be particularly important to help CHR individuals build insights into the psychotic nature of their symptoms.

The three women with CHR in this study might have been capable of handling their roles as patients, daughters, or family members, but they had difficulty fulfilling their larger society roles. When faced with greater responsibility outside their immediate support network, they all followed a similar coping style that included hiding their symptoms from others in their school or workplace. Given the very high stigma associated with psychosis in the People’s Republic of China, one might think it advisable to avoid exposing psychotic patients to others. However, concealing all feelings and thoughts about psychotic experiences might lead to erroneous judgments of others’ thoughts and interfere with insights about the psychosis. It could also create internal conflicts about their experience and how others perceive them.20

None of the cases reported here were treated by a professional clinician skilled at psychotherapy or psychosocial therapy. Generally, Chinese clinicians have a bias to treat psychotic symptoms only with medication. Although the current literature21–23 on interventions at the prodromal stage does not adequately address what kind of therapy would be appropriate in Chinese society, it is universally agreed upon that some type of treatment for the CHR population is warranted. Given that daily functioning and the overall quality of life for CHR individuals is severely affected by psychotic symptoms,24 and that these symptoms are often “cognitive” in nature, a cognitive therapy25 that focuses on either clinical symptoms or interpersonal functioning should be implemented. In addition, alternative treatments or adaptations that are sensitive to Chinese culture may be needed. Moreover, since the three individuals in this study all sought help from their families, psycho-education for families is essential and may be especially helpful in the People’s Republic of China.

We offer two suggestions for dealing with the social exclusion of CHR individuals. First, an intervention center that provides early psychosis services targeted toward CHR individuals should be established. These services could be provided by a team of psychologists, psychiatrists, volunteers, and “non-converters” (peers who had previously experienced psychotic symptoms but no longer meet the CHR criteria). The center could then act as a cushion between the pressure experienced from psychotic symptoms and social exclusion. Second, in order to minimize the risk of progression to psychosis, clinicians and family members might consider insight-oriented supportive education26 for CHR persons, rather than focusing only on the effectiveness of medication or the individual’s performance at school or at work.

Overall, a lack of social activities in CHR individuals may be a risk factor in the development of psychosis and a mediator of functional sequelae in psychosis. Since it may not be feasible for CHR persons in the People’s Republic of China to disclose their psychotic symptoms to colleagues or classmates, therapy that supports greater insights into symptoms or service that provides a forum in which those with CHR can discuss their psychotic symptoms may help these individuals overcome their difficulties.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81201043, 81171267, 81171280, 81261120410, and 81361120403), Shanghai Municipal Natural Science Foundation (12ZR1448400), Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (15411967200), National Key Clinical Disciplines at Shanghai Mental Health Center (Office of Medical Affairs, Ministry of Health, 2011-873; OMA-MH, 2011-873), Shanghai Key Laboratory of Psychotic Disorders (13dz2260500), Doctoral Innovation Fund Projects from Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (BXJ 201345), Shanghai Jiao Tong University Foundation (14JCRY04 and YG2014MS40), and by a Fogarty and National Institutes of Mental Health grant (1R21 MH093294-01A1) from the USA. The authors wish to thank the participants and study team in Shanghai.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics C. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511(7510):421–427. | ||

Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, et al. Prospective diagnosis of the initial prodrome for schizophrenia based on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes: preliminary evidence of interrater reliability and predictive validity. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(5):863–865. | ||

Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, McGorry PD. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr Res. 2004;67(2–3):131–142. | ||

Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first-episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2): 353–370. | ||

McGorry PD, McFarlane C, Patton GC, et al. The prevalence of prodromal features of schizophrenia in adolescence: a preliminary survey. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;92(4):241–249. | ||

Mishara AL. Klaus Conrad (1905–1961): delusional mood, psychosis, and beginning schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):9–13. | ||

Yung AR, Nelson B, Stanford C, et al. Validation of “prodromal” criteria to detect individuals at ultra high risk of psychosis: 2 year follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2008;105(1–3):10–17. | ||

Yung AR, Stanford C, Cosgrave E, et al. Testing the ultra high risk (prodromal) criteria for the prediction of psychosis in a clinical sample of young people. Schizophr Res. 2006;84(1):57–66. | ||

Fusar-Poli P, Bonoldi I, Yung AR, et al. Predicting psychosis: meta-analysis of transition outcomes in individuals at high clinical risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(3):220–229. | ||

Zhang T, Li H, Woodberry KA, et al. Prodromal psychosis detection in a counseling center population in China: an epidemiological and clinical study. Schizophr Res. 2014;152(2–3):391–399. | ||

Loewy RL, Pearson R, Vinogradov S, Bearden CE, Cannon TD. Psychosis risk screening with the Prodromal Questionnaire-brief version (PQ-B). Schizophr Res. 2011;129(1):42–46. | ||

Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, et al. Prodromal assessment with the structured interview for prodromal syndromes and the scale of prodromal symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(4):703–715. | ||

Cornblatt BA, Lencz T, Kane JM. Treatment of the schizophrenia prodrome: is it presently ethical? Schizophr Res. 2001;51(1):31–38. | ||

Haroun N, Dunn L, Haroun A, Cadenhead KS. Risk and protection in prodromal schizophrenia: ethical implications for clinical practice and future research. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(1):166–178. | ||

O’Connor JA, Wiffen B, Diforti M, et al. Neuropsychological, clinical and cognitive insight predictors of outcome in a first episode psychosis study. Schizophr Res. 2013;149(1–3):70–76. | ||

van Baars AW, Wierdsma AI, Hengeveld MW, Mulder CL. Improved insight affects social outcomes in involuntarily committed psychotic patients: a longitudinal study in the Netherlands. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(7):873–879. | ||

Pijnenborg GH, van Donkersgoed RJ, David AS, Aleman A. Changes in insight during treatment for psychotic disorders: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2013;144(1–3):109–117. | ||

Comparelli A, Savoja V, De Carolis A, et al. Relationships between psychopathological variables and insight in psychosis risk syndrome and first-episode and multiepisode schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201(3):229–233. | ||

Pijnenborg GH, Van der Gaag M, Bockting CL, Van der Meer L, Aleman A. REFLEX, a social-cognitive group treatment to improve insight in schizophrenia: study protocol of a multi-center RCT. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:161. | ||

Norman RM, Windell D, Lynch J, Manchanda R. Parsing the relationship of stigma and insight to psychological well-being in psychotic disorders. Schizophr Res. 2011;133(1–3):3–7. | ||

Petersen L, Nordentoft M, Jeppesen P, et al. Improving 1-year outcome in first-episode psychosis: OPUS trial. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2005;48:S98–S103. | ||

Marshall M, Rathbone J. Early intervention for psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(4):CD004718. | ||

Marshall M, Rathbone J. Early intervention for psychosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(6):CD004718. | ||

Ballon JS, Kaur T, Marks II, Cadenhead KS. Social functioning in young people at risk for schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2007;151(1–2):29–35. | ||

Morrison AP, French P, Walford L, et al. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultra-high risk: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:291–297. | ||

Langdon R, Ward P. Taking the perspective of the other contributes to awareness of illness in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(5):1003–1011. |

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2015 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.