Back to Archived Journals » Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Health » Volume 3

Intellectual property protection in India and implications for health innovation: emerging perspectives

Authors Basant R, Srinivasan S

Received 15 April 2015

Accepted for publication 3 November 2015

Published 12 April 2016 Volume 2016:3 Pages 57—68

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/IEH.S56236

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Rubin Pillay

Rakesh Basant,1 Shuchi Srinivasan2

1Department of Economics, Indian Institute of Management, 2Doctoral Student Public Systems Group, Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, India

Abstract: This paper undertakes a review of available studies to provide a perspective on the role of intellectual property (IP) protection in developing health care innovations in India. The relevant literature in the context of India has followed two strands: some studies focus on the implications of the new IP regime on access to health care, while others explore the implications of IP on innovation in general and medical innovation in particular. We argue that while it is not possible to attribute all types of innovations to changes in the IP regime, there is merit in viewing health care access and innovation as complementary and not dichotomous processes. We explore this relationship by discussing innovations undertaken by the Indian pharmaceutical industry and in health policy to balance the twin goals of invention and affordable health care.

Keywords: Abbreviated New Drug Application, Indian pharmaceutical industry, Indian IP policy, IP regime, Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana, TRIPS

Introduction

With the advent of Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), the intellectual property (IP) regimes have changed in most World Trade Organization member countries. TRIPS agreement sought to harmonize IP protection across World Trade Organization member countries so that a minimum level of protection is available to all inventions in various sectors. India also came up with its own version of TRIPS-compatible IP regime which has been hailed by some as a “model” regime for developing countries, while others are not convinced that it will provide the right incentives for medical innovation and enhance access to health care. This paper undertakes a review of available studies to provide a perspective on the role of IP protection in developing health care innovations. Broadly, the relevant literature in the context of India has followed two strands: some studies focus on the implications of the new IP regime on access to health care, while others explore the implications of IP on medical innovations. Interestingly, the two strands do not converge. Moreover, many studies view IP driven innovations as a constraint on access as these are expected to be monopolized by the IP owner. We argue that there is merit in viewing health care access and innovation as complementary processes. This is particularly the case when one defines “health innovation” more broadly to include: 1) product innovations in drugs; 2) process innovations in pharmaceutical industry; 3) new drug delivery mechanisms, bio-enhancers that improve bio-availability/efficacy and dosage forms; 4) product innovations in medical equipment and devices; 5) innovations in the delivery of health services; and 6) policy innovations to enhance access to health care.

It is not always possible to attribute all the aforementioned changes to the change in the IP regime as firms and governments strategically innovate for a variety of reasons. However, in this review, we focus on two types of “innovative responses” that may affect health care access and innovation, as these may be, at least partly, a response to the changes in the IP regime:

- Changes in innovation inputs and outputs, reviewing studies that capture implications of IP for changes in research and development (R&D), technology licensing/collaboration, patents, and other innovations at the firm level.

- Institutional/policy innovations in the health care sector to provide better access to health care. For the purpose of this article, all policy experiments in this space are seen as ‘innovative’ even though these may not be globally ‘novel’.

The following section provides a broad overview of the Indian pharmaceutical industry and health care provision in India. The “Changes in the IP regime and IP policy innovations” section briefly discusses the changes in IP policy in recent years to help appreciate other policy and health-related innovations. The subsequent three sections summarize the insights from the literature and available evidence on the two dimensions described earlier. The final section concludes the review.

Pharmaceutical industry and health care provision in India: an overview

Pharmaceutical industry in India

The Indian pharmaceutical industry remained import dependent until 1972, deeming most of the drugs unaffordable.1 Political and policy developments in the early 1970s such as the new patent acts of 1972 and Drug Price Control Order (DPCO), 1970, laid the foundation for a strong pharmaceutical industry in India. The Patent Act of 1972 did not allow product patents in pharmaceuticals and DPCO put a large number of drugs under price control.2 Public sector focus on pharmaceutical industry and policies that curbed control of multinationals added to the policy environment that was conducive for the growth of domestic firms and established India as a major supplier of pharmaceutical drugs across the world.2 In the pre-TRIPs regime, the absence of product patents allowed local production of patented drugs at a fraction of the original cost while process patents encouraged generic companies to reduce the production costs of drugs. India’s compliance with the TRIPS regime that became complete in 2005 and allows product patents has changed strategic options of Indian pharmaceutical firms.

In the year 2013, the Indian pharmaceutical industry was the “third largest in the world in terms of volume (units)”,3 estimated to be worth US$10 billion in 2010.4 The Indian pharmaceutical industry is the 14th largest in terms of value and is responsible for 10% of global drug production.3 Of approximately 10,500 manufacturing plants engaged in the production of drugs and pharmaceuticals, only approximately 23% produce bulk drugs; the remaining are engaged in the manufacturing of formulations. Most of these plants are in the unorganized/small sector with only 250–300 that can be categorized as organized or medium/large.5 The Indian pharmaceutical industry also has a very skewed distribution with the top ten companies accounting for almost 37% of the market revenue.6 Generic manufacturers dominate the Indian pharmaceutical industry and remain pivotal in providing essential drugs at affordable prices. Patented drugs, on the other hand, comprise ~1% of the pharmaceutical market in the country.7 Additionally, inventive activity has been picked up since the arrival of TRIPS with an increase in R&D expense undertaken by pharmaceutical firms.8 Reports suggest that in 2013 Indian pharmaceutical imports amounted to USD 2.7 billion and exports amounted to USD 8.9 billion.9 The trends are reflective of steady development of the pharmaceutical industry.

Health care in India

Historically, health policy in India has centered on the idea of equity. Recently, it has been broadened to incorporate the subject of universal healthcare or the provision of affordable health care extended to all citizens of a country. Despite the focus on equity, accessibility, and quality, India shoulders a high morbidity and mortality burden,10 and requires innovative solutions to reduce them.

Postindependence, the State in India intervened directly in the health care sector by providing health services through a chain of public hospitals and primary health centers. But a variety of deficiencies plagued the efficacy of the health care system. One of the central drawbacks has been limited expenditure in the sector11,12 The National Health Policy, 2002, directed the State to commit to universal health care through a “realistic” consideration of capacity.13 The policy document identified its limited capacity (infrastructure and resources) as a key challenge toward making health care available to all.

Expenditure on health has remained only approximately 1% of the GDP in 2011–2012.14 Over the years, the State’s inability to provide for the health needs of the population has resulted in the growth of the private health care sector. Currently, Indian health care is one of the most privatized systems in the world in terms of share of health spending in the private sector.11,15 The State’s strategy to withdraw from the public provision of health care has been criticized due to the associated increase in the costs of health care.11,12 Moreover, the recent move by the Federal government to reduce the health budget by 16%–17% would imply lower state involvement in the provision of public health,16 and may further increase the cost of health care for Indian households unless state governments which are expected to receive more resources from the Federal government use these resources in a more innovative and efficacious manner.

Nonetheless, the 12th Five-Year Plan (2012–2017) had outlined universal health coverage as a central goal proposing an innovative strategy of combining insurance (Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana), contracting out services, and promotion of generic drugs through prescription drug reforms.17 Such innovative policies are critical for providing affordable health care and reducing the out-of-pocket expenses on the same. A significant fraction (72%) of such expenses on health care is incurred on the purchase of drugs and other medical devices.18 Deregulation of drug prices in recent years had led to an increase in the prices of branded drugs within the country19 and price control has been brought back partially. Consequently, access to affordable medicines remains a critical issue and any policy or other innovation that can reduce costs would be very useful.

Changes in the IP regime and IP policy innovations

As mentioned, it is not possible to easily attribute health-related innovations in recent years to the new TRIPS regime as a variety of other confounding factors are at work. Therefore, we do not posit any such linkage. This section provides a brief summary of the new IP regime that highlights the policy innovations the Indian government has undertaken as a part of the new regime. Additionally, the section identifies a few IP policy gaps that have surfaced and need correction.

As discussed, the earlier IP regime’s protection of process and not product inventions resulted in Indian firms’ focus on process innovation and building of capabilities to produce bulk drugs in a very cost-effective manner. There is no consensus on the impact of the new IP regime on the innovation climate in the Indian pharmaceutical industry; while some suggest that the impact has been positive20,21 others argue that the impact has been negative or insignificant.22,23 Still others argue that the jury is still out as interesting firm responses in terms of innovation can be seen.24

While the protection of product patents in the TRIPS-compliant IP regime restricts the reverse engineering options of domestic firms and may potentially increase prices of drugs, some provisions exist to protect domestic consumers and manufacturers.22 These have taken the form of conditions for compulsory licensing (Section 84)e and standards of patentability (Clause 3[d]). Compulsory license provides national governments to allow manufacturers/ companies to replicate products and processes under patent. The license can be given, three years after the issuance of a patent if “the reasonable requirements of the public with respect to the patented invention have not been satisfied” or “the patented invention is not available to the public at a reasonable price” or “the patented invention is not worked in India”. On the other hand, Clause 3(d) states that the discovery of a variant of an existing substance or process that does not enhance efficacy significantly is not patentable. The clause attempts to discourage frivolous inventions. These provisions attempt to balance the two ideals of ensuring “access to medicines” and fostering innovation.

Policy innovation to avoid evergreening

In the year 2006, Novartis applied to the Indian Patent Office seeking a patent for its formulation Glivec®. The application was rejected as the Indian Patent Office viewed the move as an attempt toward “evergreening”. Evergreening refers to the practice adopted by inventors of patented products to extend the monopoly benefits offered under a patent.25 The practice is not legally identified but combines a variety of strategies that leverage on legal and technical deficiencies in the patent law.26 Glivec or imatinib mesylate is a formulation used in the treatment of blood cancer or chronic myeloid leukemia and costs US$1,800 per month. On the other hand, the generic variant of the drug for the same duration is available in India for approximately US$120.

TRIPS required that countries, not providing product patents in respect of pharmaceuticals and chemical inventions, put a mechanism in place for accepting product patent applications with effect from January 1, 1995. Such applications were to be examined for patent grants, after making suitable amendments in the national patent law. This mechanism of accepting product patent applications is called the “mail box” mechanism. Novartis applied for a patent in the year 1998, and in 2005, was granted exclusive marketing rights and the application was “mailboxed” for consideration.27 The patent application was rejected under Clause 3(d) of the Indian Patent Act on the grounds that the formulation was a “modification” of the existing drug and does not enhance efficacy adequately.4,27 Post the rejection of the plea in 2006, Novartis challenged the decision in the Supreme Court of India. The court backed the ruling and rejected Novartis’ appeal for a patent in 2013. It has been suggested that since the Indian patent legislation does not define “efficacy”, the differences in interpretation of this term led to the rejection of the appeal.4 More recently, Gilead’s hepatitis C drug was also denied patents on similar grounds.28

On March 4, 2015, using Article 3(d) the Indian Patent Office revoked Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co’s patent covering the drug “Spiriva®” in a response to a postgrant opposition filed by the Indian generic drug maker, Cipla. Interestingly, a pregrant opposition was also filed by another domestic firm in 2007 but the patent was granted.3

Compulsory licensing

In 2012, Natco Pharma was granted a compulsory license to manufacture a generic variant of the drug Nexavar. Nexavar is the original formulation of Bayer and is used in treating kidney and liver cancer. The drug costs US$5,500 per month with regard to the generic variant that costs US$141.6,29 Bayer contested the license in the Indian court and lost.29 The arguments used were that the drug availability did not meet the reasonable requirements of the public, that it was not reasonably affordable, and was not sufficiently worked in India, not being locally manufactured.

Some issues relating to the validity of the patent

The Indian IP policy has received criticism as it is seen to favor domestic manufacturers.4,6 Both the patentability and compulsory licensing criteria have been criticized, apart from cumbersome patenting procedures.30 However, while some provisions reported above are expected to enhance access and ensure that genuine inventions (pharmaceutical products and processes that possess marked novelty with respect to other products in the market) get patented, some others may deter inventive/innovative activity among small and medium enterprises31 as they do not possess deep pockets to engage in technology transfers, marketing, new drug discovery, and acquisitions.32 For example, Section 13(4) under the patent act asserts that granting of a patent to the inventor does not automatically ensure its validity. This ambiguity in the law can prove detrimental to small Indian firms investing in R&D.

The process of granting a patent requires the application to go through a number of filters to validate the patentability of the invention. Once the conditions of novelty, nonobviousness, and industrial application are satisfied, the patent is granted. Like in many other countries, the Indian Patent Act has provisions for pre- and postgrant opposition, which some find quite onerous.30 But these enhance the efficacy of scrutiny and, as discussed earlier, have helped revoke patents. However, the presence of Section 13(4) “incentivizes” copying as it stalls infringement action. These, combined with the delays in the judicial process, work against the inventor and undermine the technical and legal checks provided by the pre- and postgrant opposition processes. Indeed, there have been cases in which large firms have copied inventions of small pharmaceutical firms in India adding significantly to the costs of protecting Intellectual Property Rights by the inventive small and medium enterprises. The case of the 75 mg/mL Diclofenac Injection by Troikaa Pharmaceuticals is a case in point, suggesting that Section 13(4) can be dysfunctional. In February, 2005, Troikka pharmaceuticals filed for a patent for its invention: the 75 mg/mL Diclofenac Injection, an anti-inflammatory drug. In the following years other companies filed for patent applications presenting a formulation similar to that of Diclofenac injection. Additionally, the grant process was delayed due to the procedural hurdles in the form of measures for pregrant and postgrant oppositions. The apparent infringement by Glenmark Pharmaceuticals of the patented process developed by a small firm Symed to make Linezolidprovides a similar example.33,34 Notably, the courts in the USA and Europe treat the patent valid and thereby curb frivolous challenges and facilitate quick infringement action.35

Innovations in the Indian pharmaceutical industry

This section discusses technology innovations and strategic responses by pharmaceutical firms including changes in R&D expenditures and organizational innovations. Studies36,37show that organization-level changes have accompanied the changes in IP regime. While some authors38 argue that the new regime has provided India with the opportunity to “exploit” its advantage at reverse engineering and “explore” the area of enhanced R&D in medical innovation, others7 suggest that the Indian pharmaceutical industry has been adversely affected by the policy change.

Manufacturing capability and Abbreviated New Drug Application approvals

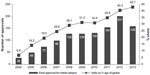

The dominant perspective, however, is that given the focus on process innovation during the pre-TRIPS period, India acquired a competitive advantage in the production of quality bulk drugs. This initial strength in “imitative” capabilities provided a fertile ground to develop “innovative” capacities with changes in technology and policy.39 Consequently, the number of US Food and Drug Administration approvals obtained by Indian pharmaceuticals has greatly increased. Exploiting this opportunity with better production processes, India is currently one of the leading generic drugs manufacturers. In fact, India manufactures eight out of the ten “blockbuster drugs”.25 Additionally, the process innovation driven building of manufacturing capabilities, fostered by the pre-TRIPS regime, has helped Indian pharmaceutical firms capture a significant share of Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) approvals in the US. ANDA is an application for a US generic drug approval for an existing licensed medication or approved drug. The applications are given to the Federal Drug Authority (FDA). In recent years, India’s share has been more than 40% (Figure 1) despite the increasing cost of compliance.

| Figure 1 Trends in Abbreviated New Drug Application approvals in the USA for Indian pharmaceutical companies. |

Trends in patenting activity

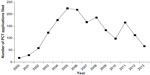

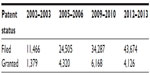

The post-TRIPS regime has witnessed higher investment in R&D.41 A detailed econometric exercise has shown a shift to a stronger IP regime that has resulted in greater thrust in the R&D activity in the sector and domestic firms have also increased patenting in India and abroad.42 Within pharmaceutical R&D, there has been an increase in the focus on novel drug discovery,42 although new dosage forms remain dominant among product patents. The patent filing activity in the Indian Patent Office has increased dramatically in recent years (Table 1). In pharmaceuticals, the top firms seem to have engaged significantly more in inventive (patenting) activity in the post-TRIPS period. The data on Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) applications (Figure 2) suggest that in anticipation of the change in the IP regime in India in 2005, the top Indian pharmaceutical firms showed an increase in inventive activity. In the subsequent period, there has been a decline in PCT applications by these pharmaceutical firms. Although, the reasons for this decline are not very clear, a study has observed a global downtrend in the patent applications during the crisis period in the late 2000s and beyond.43

| Figure 2 Total Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) applications filed by top ten Indian pharmaceutical companies. |

| Table 1 Status of patents filed at the Indian Patent Office |

A comparison of the patenting activity of the top eleven large pharmaceutical companies during the period 1999–2009 has brought out some interesting patterns.8 During 1999–2004, when product patents in pharmaceuticals were not permitted, a much larger share of applications were related to inventions in the field of new/improved processes to make products than for the products themselves (Figure 3). There has been an increase in the product patent applications filed by large Indian pharmaceutical companies (including multinational subsidiaries) after 2005 (Figure 4). The Figure presents the patent application filed by several companies (both Indian and otherwise) between the years 2005 and 2009. As can be seen, Indian companies such as Ranbaxy and Cadila remained active. The product-related applications include intermediates and formulations with maximum contribution from modified release dosage forms. Besides, most top companies are increasingly using the PCT route for filing patent applications.8 Patenting by small and medium enterprises in the sector is, however, small although as we shall see in the section “Entrepreneurial innovation” patenting is widely prevalent among start-ups in this sector.

| Figure 3 Patent applications filed in India (1999–2004). |

| Figure 4 Patent applications filed in India (2005–2009). |

Apart from new drug discovery, a number of firms are also participating in Novel Drug Delivery Systems. Firms such as Ranbaxy, Alembic, and Dabur have been able to produce Novel Drug Delivery Systems formulations with great success and have as a result also entered into licensing agreements with foreign players.45 In an earlier study, it was shown that while few pharmaceutical and biotech firms in India patent in the USA, a significant proportion (ranging from 48% to 59% depending on the estimates used) of these firms have product claims. However, most (~55%) of these applications are for incremental inventions including those relating to bio-enhancers,46 new dosage forms, new use, and Novel Drug Delivery Systems.24

In vaccine development, Rotavac vaccine presents a salient example of indigenous innovation. Rotavirus diarrhea is a major cause of death among several children from poor socioeconomic backgrounds. Estimates suggest that rotavirus accounts for 37% of diarrhea-related deaths globally and 22% of diarrhea-related deaths among the under-five age group in India.47,48 Pioneered by Indian pharmaceutical company, Bharat Biotech, and some public sector entities, the three-dose vaccine displayed 56% higher efficacy than available alternatives and is available at a fraction of the current cost. This provides an example of tropical and other diseases where the magnitude presents a profitable opportunity to innovate and achieve economies of scale and low-cost solutions.

Despite the evidence of higher inventive activity, studies in the domain of biotechnology provide divergent perspectives; while some argue that the changed patent regime has benefitted in the take-off of this knowledge intensive sector,25 others suggest that it may not have contributed at all.49 But all the studies reviewed make a case for the immense potential the sector holds in delivering for the medical needs of the future. The writings recommend focus on off-patent products such as bio-generics, vaccines, and diagnostics, arguing that reengineering is the true edge required for establishing Indian biotech competence on an international stage.49 Besides, given the decentralization of drug development process, Indian firms are finding niches to become part of the international R&D networks.24

The pipeline of innovations

A study of 165 health products in the pipeline in People’s Republic of China, India, and Brazil showed interesting patterns.50 Of these, 55% were Indian innovations with a sharp focus on chemistry-based innovations and on vaccines for communicable diseases. On the other hand, People’s Republic of China focused somewhat more on biotechnological innovations and Brazil on plant-based ones.50 Approximately 82% of the products surveyed were targeted toward therapeutic interventions, and 18% of the identified innovations were vaccines. Interestingly, approximately 10% (16) of the surveyed innovations had an exclusive focus on diseases concentrated in the developing world (mainly vaccines) while 90% of them focused on global diseases that affected both the developing and developed countries. The study also showed that almost all of Chinese and Brazilian and 83% of the Indian innovations were developed or discovered by domestic research institutions. Only 17% of the innovations in India relied upon technological in-licensing.

Entrepreneurial innovation

High penetration of mobile phones and the Internet in India have fostered a variety of innovative medical devices and health care solutions. Many of these have been introduced through startups as these increasingly provide profiTable business opportunities and also have a social impact by enhancing health care access. Many of these innovations currently lie outside the ambit of TRIPS and, once scalable, hold great potential to address a variety of public health concerns.

While there is a fair bit of entrepreneurial activity in health care provision, many IP-based biomedical startups have also been setup in recent years. Unfortunately, there is no systematic database of such startups. A recent survey of 50 such companies by Dr Gayatri Saberwal has brought out two very interesting features (based on a personal communication):51

- There is a fair bit of diversity among these IP-based biomedical startups. Firms provide diagnostics products, biologics and services, medical devices, small molecule drug discovery, chemistry-based, or other drug discovery services and software-based services.

- Almost all (44 out of 50) either have some sort of IP or plan to have it in future. More than 50% (27) of these firms have either filed for patents or have patents issued in their name and an additional 20% (ten) plan to file for patents. Interestingly, apart from protecting their technologies from imitation, patenting is used by them to attract venture capital, enhance reputation, and improve their bargaining power in inter-firm deals.

Innovation possibilities in medical devices seem quite high. Available estimates suggest that the market size of this sector in India is approximately US$2,400 million5 and is growing at the rate of 16% annually.52 Approximately 75% of the medical devices available in India are imported.53 Entrepreneurship in this arena has targeted low-cost innovative solutions but in the absence of the required resources (infrastructure, capital, and technical know-how), innovations in nondrug-based products remain gravely underinvested.

Broadly, innovative entrepreneurial solutions in health care have taken three forms: replacing, supplementing, and enabling the public sector or established private sector endeavors in this space. Replacement aims to occupy the space inadequately covered by the public/private sector; Aravind Eye Care that aims to target eye illnesses and blindness in cost-effective manner is an example. Similarly, emerging telemedicine-based solutions like eVaidya54 can replace several health care initiatives.

Several new devices can supplement the services that are currently being provided by existing health care systems or be enablers to make them more efficacious by supporting the paramedics, frontline health workers, and primary health centers with technology. The innovation of Swasthya Slate55 (Health Tablet) is a prime example that facilitates “decentralized” diagnosis by local health workers/amenities. Similarly, diagnostic equipment, 3Nethra developed by a startup, Forus,56 is revolutionizing remote decentralized screening of a variety of eye ailments. In the same vein, innovations such as Biosense57 and those by Achira58 are easy to maneuver diagnostic devices that aim to take testing and diagnostic services to each household. While one innovation assists in noninvasive hemoglobin level testing, the other is dependent upon micro fluids to diagnose tuberculosis. Innovations such as a Windmill59 and Embrace60 address the issue of infant mortality. Other innovations include low-cost sanitary napkins,61 devices to monitor cardiac in low-resource scenarios and low cost health products (eg, Bigtec Holdings is currently producing low cost insulin for sale in the Indian market57).

Given the health care needs of the nation, such innovations have thus far targeted affordability and ease of use. A critical challenge to popularizing the technologies is the cumbersome and expensive process of accessing administrative approvals of diagnostic tools.53

Strategic response and innovation

Kale62 argues that the new patent regime has led to organizational learning to provide strategic response to the changed situation. The learning has been both internal, focused toward developing stronger processes, and external with firms interacting with foreign partners. Foreign collaborations, joint ventures, and acquisitions have increased significantly to leverage existing innovation capabilities and access marketing and manufacturing capabilities.30,63 There has also been significant consolidation within the Indian pharmaceutical industry with a lot of mergers and acquisition activity suggesting the need of a large size to compete effectively in the new business environment.64

Overall, the trend seems to be that Indian firms, at least the larger ones, are adopting strategies to remain competitive in this knowledge-intensive sector with a sharp focus on building technological capabilities.24 Besides, in order to make up for the “late-mover” disadvantage, Indian firms have acquired absorptive capacities and have begun importing technology and other inputs. Guennif and Ramani65 provide a comparative analysis of “catch-up strategies” in Brazil and India under a national system of innovation framework. The authors conclude that the system of catching up has adopted a three-step process, by enhancing capabilities toward “production”, “re-engineering”, and finally “new drug discovery”.

R&D expenditures in the pharmaceutical industry have seen a sharp increase while reliance on technology purchase seem to have declined; the share of technology purchase expenditure as a proportion of sales has declined and is less than 1% while that of R&D is more than 5%, showing a remarkable increase (Table 2). Presumably, foreign technology is now coming in through foreign direct investment, rather than arms-length technology licensing arrangements, which is now feasible given the liberal foreign direct investment regime in the industry.

| Table 2 Trends in research and development (R&D) and technology purchase in the Indian pharmaceutical industry |

Public policy innovations

Health care access and innovations in health care provisioning are often not seen as complementary. We already discussed how entrepreneurial innovations along with product/process innovations can potentially be complementary. Given the possibility of increases in health care costs with the new IP regime, policy innovations become necessary to ensure affordable access to health care services. In this section, we discuss some of these health policy-related innovations as issues relating to IP policies have already been highlighted in an earlier section.

A high percentage of the out-of-pocket expenditure incurred on health care can be attributed to the purchase of drugs. The high price of patented drugs poses a barrier to universal access to health care. Horner3 argues that TRIPS-compatible IP regime would not bring any additional benefit to the population in the developing world as increasing number of pharmaceutical firms would be oriented toward lucrative Western markets with nations such as India continuing to be the “pharmacy of the developed world”. This is not necessarily the case as we have seen several firms focusing on developing country diseases and public health concerns – a few of these concern developing drugs to control pandemic influenza,66 malaria,67 and tuberculosis68 in developing countries, medication for intestinal worms,69 and setting up research centers70 that focus singularly on developing world diseases.

Other factors that may contribute to rising prices are: marketing practices adopted by pharmaceuticals along with weakening of DPCO. Marketing practices employed by several pharmaceutical companies aim to influence doctors to prescribe drugs by certain companies71,72 The high cost of these prescribed drugs and diagnostic services escalates the costs associated with treatment and might even deter several households from seeking treatment for ailments.

DPCO that came into force in 1970 was instrumental in controlling the price of essential drugs. DPCO has the authority to monitor the prices of the drugs listed under the National List of Essential Medicines. The essential drugs list offers reference prices based on the lowest price alternative to make essential drugs affordable to all. The price regulation is carried out by the National Pharma Pricing Authority. DPCO monitored the prices of 75 drugs in 1995 and by 2002 only 30 drugs remained under price control. An argument supporting the trend maintains that due to rising competition in the Indian drug market, drugs are already priced very low36; while an alternate view maintains that the number of drugs under price control in the essential drug list must be increased.73 In a policy reversal in 2013, DPCO brought 348 essential drugs within its purview.9 The intervention is aimed toward controlling the expenditure incurred upon medical bills and demolishing the cost barrier to accessing health care.

Recognizing the importance of keeping the drug prices affordable in the current context of the liberalized economy and the new IP regime, a few policy experiments seem noteworthy:

- The recent legislation – Uniform Code of Pharmaceutical Marketing Practices – aims to control the unethical and unwanted prescriptions and to ensure access to health for all. The legislation is currently voluntary in nature and mandates doctors to prescribe generic brand names. The current legislation is not a new development but is another effort to control the unethical practices and alliance between pharmaceutical companies and doctors.

- Introduced in the year 2008, Jan Aushadhi scheme aims at making low-cost and quality generic drugs available for sale to the general population. The ambitious project took off from Amritsar in the state of Punjab and at present 40 such stores have come up. The Jan Aushadhi scheme aims to enhance access, availability, and affordability.74,75 Spearheaded by the Department of Pharmaceuticals, Government of India, Jan Aushadhi aimed at popularizing the sale and purchase of quality generic drugs76 and to reduce the significant out-of-pocket expense incurred on the purchase of medicines for medical treatment.18

- Other state-based initiatives (Tamil Nadu Medical Services Corporation model, Nirmalaya) aim to enhance access to health care through the strengthening of supply side procedures for procuring and providing high quality and low-cost generic drugs.77,78 Additional state-based initiative such as mobile medical units in Bihar79 and Madhya Pradesh80 offers the communities located in difficult and remote topographies greater access to health care.

It is our belief that entrepreneurial solutions discussed earlier may enhance the efficacy of such interventions.

Some concluding observations

As in many other developing nations, introduction of TRIPS-compatible IP regime has generated a lot of debate in India. In general, the debate has focused more on pharmaceutical and food sectors as these affect access to food and health care, two of the most critical human needs. The case of India is different from many other countries given its capabilities in the pharmaceutical industry. The data on health-related innovations are fragmented and sketchy and therefore it is not easy to unequivocally answer the question if the new IP regime has fostered inventive and innovative activity in the Indian health care sector. The Indian pharmaceutical firms have shown a higher propensity to invent and patent although their R&D focus may have shifted somewhat in favor of Western markets. While there is also a shift in favor of product inventions, not many of these are new chemical entities but new dosage forms and drug delivery mechanisms. There is a lot of activity in the medical devices domain although it is not clear to what extent it has been impacted by the new IP regime. Strategic forays into foreign nations to acquire technology and consolidation in the domestic market seem to be a prerequisite for Indian firms to deal with the increasing technology-based competition. Moreover, Indian firms have been quite active on this front. The recent decline in PCT applications is puzzling and needs to be explored. The emergence of IP-based startups and social ventures in the health care space is noteworthy. Given the penetration of the Internet and mobile technologies, supporting such initiatives is critical for health care access in the near future. Apart from policy innovations to enhance the access and affordability of health care services, public policy will need to be flexible to nurture and encourage such experiments. Such flexibility is critical as the success of these ventures is intricately linked to the ability of the startups to get integrated with the public health care delivery system. Therein lies the essential complementarity between entrepreneurial and public policy innovations. Encouragement of entrepreneurship in the sector requires a combination of powerful financial incentives, capacity for quality research, supportive regulatory system, and an active investment community.81

As India gains more experience with the new patent regime, it will have to be cognizant of the dysfunctionalities that the new regime might have created. While the multinational corporations have complained about the criteria of patentability (Article 3[d]) and compulsory licensing (Article 84), some small firms seem to have suffered with respect to the confusion regarding the validity of the patents granted (Section 13[4]). A critical review of these seems desirable. The complaints regarding cumbersome patenting procedures seem to be common across different types of firms. Admittedly, it is a learning phase for the country and the State should be flexible enough to change policy to balance the twin objectives of creating incentives for invention and providing affordable health care.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to Troikaa Pharmaceuticals and Pulak Mishra and Gayatri Saberwal for sharing very useful insights and data, but they alone are responsible for any errors relating to facts and interpretation.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Mohammad A, Kamaiah B. The Indian pharmaceutical industry in post-TRIPS and post-product patent regime: a group-wise analysis of relative efficiency using nonparametric approach. IUP J Appl Econ. 2014;13(1):47–61. | |

Basant R. Intellectual property rights regimes: comparison of pharma prices in India and Pakistan. Econ Polit Wkly. 2007;42(39):3969–3977. | |

Horner R. The impact of patents on innovation, technology transfer and health: a pre-and post-TRIPs analysis of India’s pharmaceutical industry. New Polit Econ. 2014;19(3):384–406. | |

Gabble R, Kohler JC. To patent or not to patent? the case of Novartis’ cancer drug Glivec in India. Global Health. 2014;10:3. | |

Planning Commission, Government of India. Report of the Working Group on Indian Pharmaceutical Industry for the Twelfth Five Year Plan (2012–2017); 2012. | |

Akhtar G. Indian pharmaceutical industry: an overview. IOSR J Humanit Soc Sci. 2013;13(3):51–66. | |

Haley GT, Haley UCV. The effects of patent-law changes on innovation: the case of India’s pharmaceutical industry. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2012;79(4):607–619. | |

Bedi N, Bedi PMS, Sooch BS. Patenting and R&D in Indian pharmaceutical industry: post-TRIPS scenario. J Intellectual Property Rights. 2013;18(2):105–110. | |

Department of Pharmaceuticals. Annual Report (2014–2015). New Delhi: Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers, Government of India. Available from: http://www.pharmaceuticals.gov.in/sites/default/files/AnnualReport201415.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2015. | |

Balarajan Y, Selvaraj S, Subramanian SV. Health care and equity in India. Lancet. 2011;377(9764):505–515. | |

Duggal R. Healthcare in India: changing the financing strategy. Soc Policy Adm. 2007;41(4):386–394. | |

Selvaraj S, Karan AK. Deepening health insecurity in India: evidence from national sample surveys since 1980s. Econ Polit Wkly. 2009;44(40):55–60. | |

MoHFW. National Health Policy. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2002. | |

Planning Commission, Government of India. Twelfth Five Year Plan (2012–2017): Social sectors (Vol III). New Delhi: Sage India; 2012:4. | |

Sengupta, Amit for Jan Swasthya Abhiyan. Universalising Health Care for All; 2012. Available form: http://www.phmovement.org/sites/www.phmovement.org/files/JSA%20Convention%20Universal%20Health%20Care%20for%20All%20-%20booklet.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2014. | |

The Economic Times (December 24, 2014). Healthcare budget may face 16%–17% cut. Available from: http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2014-12-24/news/57376350_1_healthcare-budget-ministry-public-spending. Accessed January 20, 2015. | |

Planning Commission. Twelfth Five Year Plan (2012–2017): Faster, More Inclusive and Sustainable; 2013. Available from: http://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:ess:wpaper:id:5302. Accessed February 20, 2015. | |

Kumar AK, Chen LC, Choudhury M, et al. Financing health care for all: challenges and opportunities. Lancet. 2011;377(9766):668–679. | |

Bhargava A, Kalantri SP. The crisis in access to essential medicines in India: key issues which call for action. Indian J Med Ethics. 2013;10(2):86–95. Available from: http://www.ijme.in/~ijmein/index.php/ijme/article/view/30. Accessed March 10, 2015. | |

Bouet D. A study of intellectual property protection policies and innovation in the Indian pharmaceutical industry and beyond. Technovation. 2014;38:31–41. | |

Godinho MM, Ferreira V. Analyzing the evidence of an IPR take-off in China and India. Res Policy. 2012;41(3):499–511. | |

Mani, S. Doesn’t India already have an IPR policy? Econ Polit Wkly. 2014;49(47):10–13. | |

Chaudhuri S. “Is product patent protection necessary in developing countries for innovation.” R&D by Indian pharmaceutical companies after TRIPS. Indian Institute of Management Calcutta Working Paper Series 614; 2007. | |

Basant R. Intellectual property protection, regulation and innovation in developing economies: the case of the Indian pharmaceutical industry. Innovat Develop. 2011;1(1):115–133. | |

Dwivedi G, Hallihosur S, Rangan L. Evergreening: a deceptive device in patent rights. Technol Soc. 2010;32(4):324–330. | |

Bansal IS, Sahu D, Bakshi G, Sing S. Evergreening – a controversial issue in pharma milieu. J Intellect Property Rights. 2009;14(4):298–299. | |

Chaudhuri S. Intellectual property rights and innovation: MNCs in pharmaceutical industry in India after TRIPS; Institute for Studies in Industrial Development: 2014. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sudip_Chaudhuri2/publication/282503175_Intellectual_Property_Rights_and_Innovation_MNCs_In_Pharmaceutical_Industry_in_India_after_TRIPS/links/5610d4e708ae0fc513f15974.pdf. Accessed November 28, 2015. | |

New W. Key hepatitis C patent rejected in India. Intellectual property watch. January 14, 2015. Available from: http://www.ip-watch.org/2015/01/14/key-hepatitis-c-patent-rejected-in-india-for-lack-of-novelty-inventive-step/. Accessed May 5, 2015. | |

Hirschler B. Bayer fails to block generic cancer drug in India’s top court. Reuters. 2014. Available from: http://in.reuters.com/article/2014/12/12/us-bayer-india-ruling-idINKBN0JQ1XA20141212. Accessed December 12, 2014. | |

Organization of Pharmaceutical Producers of India, OPPI (2014) Indian Pharmaceutical Industry Challenges. OPPI Position Paper. | |

Pradhan J. Strategic asset-seeking activities of emerging multinationals: perspectives on foreign acquisitions by Indian pharmaceutical MNEs. Org Markets Emerg Econ. 2010;1(2):9–31. | |

Ghatak S. Micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in India: an appraisal. J EOFEMP. 2010;2(5):1–19. | |

Patent decision document. Before Controller of Patents and Designs Release. 2003. Available from: http://ipindiaservices.gov.in/decision/00558-DELNP-2003-9637/558-delnp-2003%2025(2)%20decision.pdf. Hearing held November 21, 2014. Accessed on May 4, 2015. | |

Apoorva. Delhi HC asks Glenmark to stop making Linezolid drug. LiveMint. January 20, 2015. Available from: http://www.livemint.com/Companies/dhSmYNStp6OMQvMy7nVf6O/Delhi-HC-asks-Glenmark-to-stop-making-Linezolid-drug.html. Accessed April 20, 2015. | |

Choudhry RK. Presumption of a validity of an Indian patent; 2011. Available from: http://spicyip.com/2011/06/presumption-of-validity-of-an-indian.html. | |

Chittoor R, Ray S, Aulakh PS, Sarkar MB. Strategic responses to institutional changes: “Indigenous growth” model of the Indian pharmaceutical industry. Journal of International Management. 2008; 14(3):252–269. | |

Chittoor R, Sarkar MB, Ray S, Aulakh PS. Third-world copycats to emerging multinationals: institutional changes and organizational transformation in the Indian pharmaceutical industry. Organization Science. 2009;20(1):187–205. Accessed on April 20, 2015. | |

Kale D, Wield D. Exploitative and explorative learning as a response to the TRIPS agreement in Indian pharmaceutical firms. Indus Innov. 2008;15(1):93–114. | |

Kale D, Little S. From imitation to innovation: the evolution of R&D capabilities and learning processes in the Indian pharmaceutical industry. Technol. Anal Strateg Manage. 2007:19(5):589–609. | |

CRISIL. CRISIL Insight. India: CRISIL Limited; 2013. Available from: http://www.crisil.com/Ratings/Brochureware/News/V5-Pharma%20Article%20EdV3.pdf. Accessed on July 15, 2015. | |

Jagadeesh H, Sasidharan S. Do stronger IPR regimes influence R&D efforts? Evidence from the Indian pharmaceutical industry. Glob Business Rev. 2014;15(2):189–204. | |

Goldar B. Gupta I. Effects of new patents regime on consumers and producers of drugs/medicines in India. Report Submitted to the UNCTAD; 2013. Available from: http://wtocentre.iift.ac.in/UNCTAD/09.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2014. | |

Tyagi S, Mahajan V, Nauriyal DK. Innovations in Indian drugs and pharmaceutical industry: Have they impacted exports? J Intellect Property Rights. 2014;19:243–252. | |

Controller General of Patents, Designs, Trademarks. Annual Report 2006–2007. Office of the Controller General of Patents, Designs, Trademarks, Geographical Indications, Intellectual Property Training Institute and Patent Information System. 2007. Available from http://ipindia.gov.in/cgpdtm/AnnualReport_English_2006-2007.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2015. | |

Joseph RK. The R&D scenario in the Indian pharmaceutical industry. 2012 RIS Discussion Paper No 176. Available from: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2009229. Accessed January 30, 2015. | |

Atal N, Bedi KL. Bioenhancers: Revolutionary concept to market. Journal of Ayurveda and integrative medicine. 2010;1(2):96. | |

Bhaumik S. Rotavirus vaccine in India faces controversy. CMAJ. 2013;185(12):E563–E564. | |

Mehta, N. PM launches Rotavac vaccine. 2015. Available from http://www.livemint.com/Politics/jEMNJ3yGDmVt71upvEpQ9L/PM-launches-Rotavac-vaccine.html. Accessed on March 10, 2015. | |

Ramani SV, Maria A. TRIPS: its possible impact on biotech segment of the Indian pharmaceutical industry. Econ Polit Wkly. 2005;40(7):675–683. | |

Rezaie R, McGahan AM, Daar AS, Singer PA. Innovative drugs and vaccines in China, India and Brazil. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(10):923–926. | |

Saberwal, G. India’s intellectual property-based biomedical startups. Current Science. 2016;110(2):167–171. | |

Pulakkat H. Startups delivering sterling and innovative healthcare products; August 14, 2014. The Economic Times. Available from: http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2014-08-14/news/52807708_1_device-engineers-country. Accessed March 10, 2015. | |

Jarosławski S, Saberwal G. Case studies of innovative medical device companies from India: barriers and enablers to development. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):199. | |

eVaidya (homepage on the internet). 2014. Available from: https://www.evaidya.com/home.html#!/home. Accessed March 15, 2015. | |

Wadhwa V. This Indian startup could disrupt health care with an affordable diagnostic machine. VB News. November 18, 2014. Available from http://venturebeat.com/2014/11/18/this-indian-startup-could-disrupt-health-care-with-an-affordable-diagnostic-machine//. Accessed March 5, 2015. | |

Forus Health (homepage on the internet). 2014. Available from: http://forushealth.com/forus/. Accessed March 15, 2015. | |

Biosense Laboratories [homepage on the internet]. Available from: http://www.biosense.com/. Accessed March 15, 2015. | |

Achira Labs [homepage on the internet]. 2015. Available from http://www.achiralabs.com/. Accessed on March 15, 2015. | |

Windmill Health Technologies [homepage on the internet]. Available from http://windmillhealth.weebly.com/neobreathe.html. Accessed on March 15, 2015. | |

Embrace Innovations (homepage on the internet). 2015. Available from: http://www.embraceinnovations.com/. Accessed March 15, 2015. | |

Aakar Innovations (homepage on the internet). Mumbai; 2015. Available from: http://www.aakarinnovations.com. Accessed March 15, 2015. | |

Kale D. The distinctive patterns of dynamic learning and inter-firm differences in the Indian pharmaceutical industry. BJM. 2010;21(1):223–238. | |

Agarwal, SP, Gupta A, Dayal R. Technology transfer perspectives in globalising India (drugs and pharmaceuticals and biotechnology). The Journal of Technology Transfer. 2007;32(4):397–423. | |

Mishra P, Chandra T. Mergers, acquisitions and firms’ performance: experience of Indian pharmaceutical industry. Eurasian J Bus Econ. 2010;3(5):111–126. | |

Guennif S, Ramani SV. Explaining divergence in catching-up in pharma between India and Brazil using the NSI framework. Res Policy. 2012;41(2):430–441. | |

Pandemic Influenza and Developing Countries. Global Health Progress Web site. 2015. Available from: http://www.globalhealthprogress.org/programs/pandemic-influenza-developing-countries. Accessed September 20, 2015. | |

Roll Back Malaria: Sanofi-aventis’ access to antimalarial medicines: the impact malaria approach. Sanofi Web site. Available from: http://www.rollbackmalaria.org/files/files/news-and-events/press-releases/Sanofi-en.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2015. | |

Stop TB Partnership: The Global Plan to stop TB 2011–2015. Available from: http://www.stoptb.org/assets/documents/global/plan/tb_globalplantostoptb2011-2015.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2015. | |

Neglected Tropical Diseases: The campaign to control soil-transmitted helminthes. GlaxoSmithKline Website. Available from: https://www.gsk.com/media/267956/Soil-transmitted-helminths-factsheet-PDF.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2015. | |

Novartis Institute for Tropical Diseases. 2015. Available from: https://www.nibr.com/our-research/institutes/novartis-institute-tropical-diseases. Accessed September 15, 2015. | |

Mehta PSA. bitter pill for docs, pharma companies [newspaper]. (January 6, 2015). Available from: http://www.asianage.com/columnists/bitter-pill-docs-pharma-companies-662. Accessed January 19, 2015. | |

Kalaskar PB, Sagar PN. Product patent regime posed Indian pharma companies to change their marketing strategies: a systematic review. VSRD-Int J Business Manage Res. 2012;2(6):254–264. | |

Selvaraj S, Hasan H, Chokshi M, et al. Pharmaceutical pricing policy: a critique. Econ Polit Wkly. 2012;47(4):20–23. | |

Jayaraman K. Troubles beset ‘Jan Aushadhi’ plan to broaden access to generics. Nat Med. 2010;16(4):350–350. | |

Kotwani A. Will generic drug stores improve access to essential medicines for the poor in India. J Public Health Policy. 2010;31:178–184. | |

Department of Pharmaceuticals, Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers, Government of India. Jan Aushadhi Scheme: A New Business Plan. 2015. Available from: http://janaushadhi.gov.in/data/new_businessplan.pdf. Accessed July 3, 2015. | |

Lalitha N. Tamil Nadu Government intervention and prices of medicines. Econ Polit Wkly. 2008;43:66–71. | |

Nautiyal S. IMA to promote affordable and efficacious branded generics through Nirmalaya. (February 19, 2015). Available from: http://www.pharmabiz.com/NewsDetails.aspx?aid=86804&sid=1. Accessed February 20, 2015. | |

ArogyaRath: Mobile Medical Units (MMU) in Bihar. Center for Health Market Innovations Website. Available from: http://healthmarketinnovations.org/program/arogya-rath-mobile-medical-units-mmu-bihar. Accessed March 13, 2015. | |

Deen Dayal Chalit Aspatal (Mobile Medical Units). Center for Health Market Innovations Website. 2014. Available from: http://healthmarketinnovations.org/program/deen-dayal-chalit-aspatal-mobile-units. Accessed March 14, 2015. | |

FICCI P. PwC-FICCI-Medical_Technology_in_India.pdf. (2011). Available from: https://www.pwc.in/assets/pdfs/pharma/PwC-FICCI Medical_Technology_in_India.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2015. | |

Prowess [homepage on the internet]. Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt. Ltd. Available from: https://prowess.cmie.com/. Accessed February 9, 2015. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.