Back to Journals » Journal of Pain Research » Volume 10

Initiation of labor analgesia with injection of local anesthetic through the epidural needle compared to the catheter

Authors Ristev G, Sipes AC, Mahoney B, Lipps J, Chan G, Coffman JC

Received 29 June 2017

Accepted for publication 1 November 2017

Published 12 December 2017 Volume 2017:10 Pages 2789—2796

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S145138

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor E Alfonso Romero-Sandoval

Goran Ristev,1 Angela C Sipes,1 Bryan Mahoney,2 Jonathan Lipps,1 Gary Chan,3 John C Coffman1

1Department of Anesthesiology, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH, USA; 2Department of Anesthesiology, Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and Mount Sinai Roosevelt, New York, NY, USA; 3Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative & Pain Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA

Background: The rationale for injection of epidural medications through the needle is to promote sooner onset of pain relief relative to dosing through the epidural catheter given that needle injection can be performed immediately after successful location of the epidural space. Some evidence indicates that dosing medications through the epidural needle results in faster onset and improved quality of epidural anesthesia compared to dosing through the catheter, though these dosing techniques have not been compared in laboring women. This investigation was performed to determine whether dosing medication through the epidural needle improves the quality of analgesia, level of sensory blockade, or onset of pain relief measured from the time of epidural medication injection.

Methods: In this double-blinded prospective investigation, healthy term laboring women (n=60) received labor epidural placement upon request. Epidural analgesia was initiated according to the assigned randomization group: 10 mL loading dose (0.125% bupivacaine with fentanyl 2 µg/mL) through either the epidural needle or the catheter, given in 5 mL increments spaced 2 minutes apart. Verbal rating scale (VRS) pain scores (0–10) and pinprick sensory levels were documented to determine the rates of analgesic and sensory blockade onset.

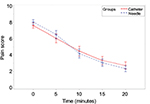

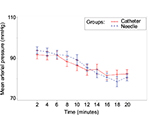

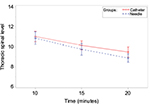

Results: No significant differences were observed in onset of analgesia or sensory blockade from the time of injection between study groups. The estimated difference in the rate of pain relief (VRS/minute) was 0.04 (95% CI: −0.01 to 0.11; p=0.109), and the estimated difference in onset of sensory blockade (sensory level/minute) was 0.63 (95% CI: −0.02 to 0.15; p=0.166). The time to VRS ≤3 and level of sensory block 20 minutes after dosing were also similar between groups. No differences in patient satisfaction, or maternal or fetal complications were observed.

Conclusion: This investigation observed that epidural needle and catheter injection of medications result in similar onset of analgesia and sensory blockade, quality of labor analgesia, patient satisfaction, and complication rates.

Keywords: labor analgesia, epidural needle, epidural catheter, analgesic onset

Introduction

Epidural and combined spinal–epidural (CSE) techniques are widely considered as the most effective means of providing labor analgesia1,2 and have been found to increase patient satisfaction compared to other modalities.2 Traditionally, the epidural catheter is placed, aspirated, and a test dose of medication is given to detect the possibility of an intravascular (IV) or intrathecal (IT) catheter prior to administering additional doses of local anesthetic and opioids. There have been very few studies in which anesthesia providers have initiated labor analgesia by injecting medications through the epidural needle immediately after loss of resistance in order to achieve faster onset of pain relief.3 Provision of neuraxial labor analgesia in a timely manner has been shown to be important to many parturients on open-ended patient surveys.4 Thus, it is important to examine the efficacy and safety of epidural dosing techniques that may shorten analgesic onset. Dosing prior to placement of the catheter, such as with a CSE or through the epidural needle, may have the additional benefit of allowing labor analgesia to commence in instances which catheter placement is in an epidural vein and additional procedure time is necessary.

In addition to faster onset of analgesia, it has been reported that dosing through the epidural needle may result in improved quality of epidural anesthesia compared to dosing through the catheter.5 However, other investigations in obstetric6 and non-obstetric7 patients receiving epidural anesthesia have observed similar onset and quality of surgical anesthesia as well as similar level of sensory blockade when dosing through the needle versus the catheter. To our knowledge, there have been no direct comparisons of needle and catheter injection of epidural medications for the initiation of labor analgesia.

The rationale for potentially improved analgesia onset with epidural needle injection is uncertain. More rapid injection is often possible through the epidural needle given the relatively larger gauge and shorter length compared to a catheter,8 which could potentially enhance the spread of medication within the epidural space. Suboptimal epidural catheter position has been suggested to play a role in limiting spread of injected medication and quality of analgesia,5 and radiological studies have demonstrated that catheter position in the anterior or lateral epidural space may lead to one-sided or asymmetric blockade.9,10 Injection from an epidural needle tip that lies in a more posterior location within the epidural space may be more likely to result in bilateral spread compared to injection through an epidural catheter, which may more likely lie in the lateral or anterior epidural space. Finally, the injection of epidural saline after loss of resistance is commonly done to reduce the incidence of an IV catheter placement,11 but this may dilute subsequent local anesthetic administered.12 Predistension of the epidural space with local anesthetic solution could still reduce the incidence of IV catheter complications, while resulting in a faster onset and higher quality of analgesia relative to predistension with saline.

There is lack of research examining the potential benefits and risks of initiating labor analgesia with injection of anesthetic medications through the epidural needle. We hypothesized that needle injection of a loading dose of bupivacaine directly into the epidural space would shorten analgesic onset and improve the quality of subsequent labor analgesia compared to catheter injection.

Methods

This study was a prospective, randomized, double-blind trial involving healthy adult parturients in spontaneous labor or induction of labor following an uncomplicated pregnancy. Enrollment for this trial spanned from January 17, 2013 to January 24, 2014 at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. The protocol was approved by the Ohio State University Biomedical Research Institutional Review Board prior to the start of recruitment and is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02883283). The research was conducted using good clinical practices and the highest standards of ethics, as described by the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were approached and they voluntarily provided written informed consent for this research upon admission to the labor and delivery unit. During the consent process, patients were made aware that they would not know whether the initial epidural medication was being administered through the epidural needle or catheter. Inclusion criteria were uncomplicated obstetric patients aged ≥18 years who were in active labor and requesting epidural analgesia. Exclusion criteria included contraindications to epidural placement, inability to provide informed consent, fetal intrauterine growth restriction, nonreassuring fetal heart tracing, cervical dilation >7 cm at the time of request for epidural, intrauterine fetal demise, spinal pathology, history of chronic pain, or incarcerated patients. If the practitioners had any suspicion of dural puncture (more than three attempts, or return of clear fluid following loss of resistance), the participant would no longer continue in the study and would receive standard catheter insertion and epidural dosing.

Patients were randomly assigned to either the control group or intervention group by randomly ordering equal numbers of each study group in sequentially numbered opaque envelopes. Upon the participant’s request for epidural analgesia, the study group was revealed to an anesthesiologist trained in the research protocol prior to proceeding with epidural placement. A separate investigator blinded to the randomized study group was also present to perform data collection. The blinded investigator was shielded from the anesthesia providers performing the epidural placement and administering medications, so that neither the blinded investigator nor the patient could see if the initial epidural medications were given via the needle or catheter.

Epidural procedures were performed by attending anesthesiologists, obstetric anesthesiology fellows, or anesthesiology residents who had completed at least 50 labor epidural procedures during their training. Patients were placed in the sitting position, the skin over the lumbar area was cleaned with ChloraPrep® (ChloraPrep Skin Prep; CareFusion, El Paso, TX, USA), a sterile drape was applied, and sterile technique was observed throughout the procedure. Skin and subcutaneous tissue were infiltrated with 1% lidocaine 3–5 mL at the intended site of epidural placement. The lumbar epidural space was then located with an 18 gauge Tuohy epidural needle via a loss of resistance technique with 2 mL or less of saline, as it is a standard practice at our institution to perform loss of resistance to saline. BBraun Perifix®ONE (B. Braun Medical Inc., Bethlehem, PA, USA) 20 gauge epidural catheters were placed in each patient either before or after administration of epidural medication according to the study group.

The patient’s verbal rating scale (VRS) pain score (0–10) during uterine contractions was determined at the time of loss of resistance location of the epidural space and at 5-minute intervals for 20 minutes. In the needle injection group, after successful loss of resistance with saline was obtained, a 10 mL loading dose of 0.125% bupivacaine with fentanyl 2 µg/mL was given in 5 mL increments via the epidural needle spaced 2 minutes apart. Between doses, the patient’s blood pressure, heart rate, and symptoms suggestive of IT or IV injection were carefully observed. In order to maintain blinding for the study, anesthesia providers stood behind the patients in the catheter injection group during this time but did not inject any epidural medication. In both study groups, the epidural catheter was then advanced and catheter aspiration performed. If the anesthesia provider was unable to readily advance the catheter in a timely manner or the catheter aspiration was positive for blood or cerebrospinal fluid, then the patient would not continue in the study and their subsequent care would be at the discretion of the anesthesia provider. Five minutes after loss of resistance, the catheter injection group then received the same 10 mL loading dose of 0.125% bupivacaine with fentanyl 2 µg/mL, given in 5 mL increments via the epidural catheter spaced 2 minutes apart. In order to once again maintain patient and investigator blinding, the anesthesia providers stood behind the patients in the needle injection group during this time without giving any epidural medication. It should be noted that the catheter dose was administered 5 minutes after the needle group to ensure that equal timing of VRS pain score and sensory blockade level assessments after medication injection would occur with both study groups, as these parameters were recorded at baseline and thereafter at 5-minute intervals. Three minutes after the last epidural catheter dose was given (or not given for patients in the needle injection group), both study groups received an epidural test dose of 1.5% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:200,000 3 mL to look for signs of IV or IT catheter placement. The epidural catheter test dose is usually administered prior to giving other medications through the epidural catheter, though for the purposes of this investigation, it was determined that the same epidural medications should be administered in the same order to enable more equal comparison of onset of pain relief and sensory blockade measured from the time of injection between study groups. Further, careful patient observation, catheter aspiration, and incremental dosing were determined to be reasonable safeguards against IV or IT administration of medication. All patients then received a standard epidural infusion of 0.0625% bupivacaine with fentanyl 2 µg/mL at 10 mL/h with patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) 10 mL doses, 20-minute lockout.

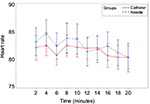

Participants were asked to rate the pain of their most recent uterine contraction on a VRS of 0–10 every 5 minutes (0=no pain, 10=worst pain imaginable) for 20 minutes beginning at the time loss of resistance occurred and just prior to the first potential dose of local anesthetic through the epidural needle. The sensory level was determined by loss of sharpness to pinprick with a blunt tip needle recorded every 5 minutes for 20 minutes after loss of resistance location of the epidural space. Primary outcome measures used to compare the epidural needle- and epidural catheter-based loading techniques included rates of analgesic (VRS/minute) and sensory blockade onset (sensory level/minute). Time to VRS ≤3 was also recorded for both groups. Maternal heart rate, fetal heart rate, and maternal blood pressure measurements were used to assess the safety profiles between study groups and were recorded every 2 minutes for 20 minutes after successful location of the epidural space. Occurrence of adverse events, such as accidental IV or IT injection of medications, was recorded. The number of PCEA demand doses and the total volume of anesthetic infused were used as metrics to assess the effectiveness of analgesia throughout the duration of labor, and these parameters were recorded after delivery. Patient satisfaction scores (0–10) were determined during routine follow-up visits 1 day after delivery.

The desired sample size for the study was 50 in total (60 were enrolled to allow for removing patients after enrollment), 25 patients per group to detect a 1.5-fold difference in rate of VRS pain score change with more than 80% and an alpha level of 0.05, assuming a conservative coefficient of variation of 50% for slopes across patients within each group. No pilot data or previously published studies were available to do the sample size calculation, though it was considered that a 1.5-fold difference between the two groups in VRS pain score would be clinically meaningful. Data were analyzed using Statistical Analysis Software, version 9.3, applying linear mixed model regression analyses for fixed and random effects between groups, while a random effect regression analysis was conducted to estimate the slopes of the outcomes over continuous time for both groups. Sandwich estimator was used to control the correlation because of the dependence of the observations among repeated measurements. Student’s t-test, chi-square test, and Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test were used to analyze demographic variables, with alpha=0.05.

Results

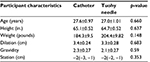

Sixty patients were enrolled to participate in this investigation. Protocol deviations occurred in 4 cases, leaving 29 patients in the catheter injection group and 27 patients in the needle injection group to be considered for the analysis. There were no significant differences in demographic or labor characteristics between the study groups (Table 1). The rate of pain relief (VRS pain score/minute) from the time of medication injection and the rate of sensory block onset (sensory level/minute) were used as primary metrics to compare the effectiveness between delivering the loading dose via the epidural needle and the epidural catheter. The estimated difference in rate of pain relief (slope) from the time of medication dosing, reported as VRS pain score/minute, between the epidural needle and epidural catheter groups was 0.04 (95% CI: −0.01 to 0.11) and not statistically significant (p=0.109; Figure 1 and Table 2). Notably, 13 of 29 patients who were dosed through the epidural catheter reported uterine contraction pain relief prior to receiving the initial dose of epidural medication. The estimated difference in analgesic spread (spinal level/minute), as defined by loss of sharpness of pinprick, was 0.63 (95% CI: −0.12 to 0.19) and did not significantly differ between groups (p=0.166; Figure 2 and Table 2). The time to VRS ≤3 for the epidural needle and catheter groups were 12.5±5.28 and 12.61±5.38 minutes (p=0.942; Table 2), respectively.

| Figure 2 Thoracic sensory level as a function of time (minutes) for 20 minutes after the initial epidural dose was administered. Notes: Data are mean±SD. Time=0, time of the initial bolus dose. |

| Table 1 Participant characteristic averages per randomization group Notes: Statistical differences calculated between participants in each randomized group. Data are mean ± SD. |

There was no significant difference observed in the average number of PCEA demand doses, with 5.85 and 4.62 PCEA doses in the needle and catheter injection groups, respectively (p=0.384; Table 2). The average total volume of anesthetic infused were 116.6 and 113.6 mL for the needle and catheter injection groups, respectively (p=0.901; Table 2). The mean number of clinician-administered epidural doses for rescue analgesia were 1.17 and 1.67 (p=0.209; Table 2) in the needle and catheter injection groups, respectively.

No significant difference was observed in the estimated slope differences of maternal mean arterial blood pressure (0.25, p=0.188; Figure 3) or maternal heart rate (0.03, p=0.807; Figure 4). No occurrence of fetal bradycardia was observed in the first 20 minutes after epidural medication dosing in either study group. No adverse events occurred in either study group. Patients were asked to rate their satisfaction (0–10) during routine follow-up visit 1 day after delivery and no significant differences were observed between study groups (needle injection: 9.2, catheter injection: 8.75, p=0.521; Table 2).

Discussion

We hypothesized that needle injection of epidural medications would shorten analgesic onset measured from the time of injection and improve the quality of subsequent labor analgesia compared to catheter injection, potentially because we thought faster injection from a more posterior location within the epidural space and improved medication spread may be possible with needle compared to catheter dosing.5,8–10 However, we observed similar rates of analgesic and sensory blockade onset measured from the time of medication injection. The quality of subsequent labor analgesia was also similar between study groups, as reflected by similar PCEA usage, clinician-administered epidural boluses, and total volume of local anesthetic administered. Instead, it may have been beneficial to measure analgesic onset from the time of epidural space location rather than from the time of injection, as this may have demonstrated a benefit in terms of shortening onset of pain relief after needle injection. Measuring analgesic onset from the time of successful location of the epidural space is also arguably a better reflection of actual clinical practice, as needle injection can be performed prior to catheter insertion, aspiration, test dosing, catheter securing, and eventual catheter dosing. Importantly, the incidence of side effects was also observed to be similar between study groups, as no statistically significant differences in maternal mean arterial blood pressure, heart rate, or incidence of fetal bradycardia were observed. However, adequate statistical power was not achieved to study the safety profile of epidural needle loading compared to catheter loading. Further investigation is warranted to more fully establish the safety of dosing through the epidural needle.

A further limitation of this study was that VRS pain scores were recorded only every 5 minutes for 20 minutes after the initial epidural dose and the rate of pain relief (pain score/minute) was reported as an outcome measure. Gambling et al asked the patient to inform the investigator when she rated contraction pain 0 or 1 (0–10 scale), which may have been a more accurate means of determining onset of analgesia in the present investigation.3 Another recent investigation assessed time from initial epidural dosing to a VRS pain score ≤3, and observed analgesic onset of 9.2 and 16 minutes in the different study groups.13 Patients may often achieve initial satisfactory labor analgesia within 20 minutes of dosing the initial epidural medication, but we acknowledge that some patients may not have effective pain relief in this time frame and a longer period of assessment should have been performed.

The optimal volume, local anesthetic concentration, and dose interval necessary to appreciate a potential benefit of dosing through the epidural needle have not been established. It is possible that administering the anesthetic solution in 5 mL increments separated by 2 minutes may have represented inadequate volume being delivered too slowly to appreciate any potential benefit of dosing through the epidural needle. The effectiveness of administering the initial bolus incrementally via the epidural needle over several minutes time may have provided greater patient safety, but limited the potential benefit in regard to shortening onset of labor analgesia and improving spread of medication. Anecdotally, larger volumes of local anesthetic given over a shorter time interval may achieve greater spread of medication and shorten the onset of analgesia. There have been considerable differences in volume and dosing intervals among studies examining dosing through the epidural needle, particularly amongst studies in obstetric6 and non-obstetric5,7 patients undergoing surgery. Only one of these reports suggested benefit of dosing through the epidural needle and reported superior surgical conditions in non-obstetric patients who received 2% lidocaine 20 mL as a single injection via the epidural needle compared to the catheter.5 We are aware of only one recent study in which laboring patients were given 15 mL of local anesthetic divided into three doses, but this dosing method was compared to CSE labor analgesia in that investigation.3 Given the potential importance of bolus volume administered and dosing interval, further investigation with increased volume and decreased time interval for injection is necessary to better evaluate the utility of epidural needle bolus dosing.

Interestingly, 13 of 29 patients in the epidural catheter group reported pain relief prior to receiving the initial bolus of anesthetic solution, suggesting a placebo effect. The blinded design of the study necessitated that patients not be aware of whether the medication was administered through the epidural needle or catheter, but the catheter medication was administered 5 minutes later. Therefore, patients in the epidural catheter group had a 5-minute time period of perceived pain reduction after loss of resistance was obtained, which may have artificially lowered patient-reported pain scores when compared with the pain scores of patients in the epidural needle group, who received the initial bolus immediately after loss of resistance was obtained. We are not aware of any evidence that saline used for loss of resistance would have an analgesic effect, and the saline volume was limited to 2 mL or less in this study. Previous authors have pointed out that patients can experience pain and anxiety during infiltration with lidocaine or labor epidural placement.14 One previous study observed slightly higher numerical verbal pain scores (0–10) after local anesthetic infiltration compared to just before threading the epidural catheter.15 It is possible that in the present investigation, some of the patient-reported pain was related to the epidural procedure itself, and the lowering of VRS pain scores in the catheter group prior to receiving epidural medication may be a reflection of a longer period of time between the epidural needle placement and medication dosing.

Some providers prefer to perform CSE procedures when shorter onset of pain relief is desired. CSE techniques have been shown to improve the onset3 and reliability3,16–18 of labor analgesia relative to epidural techniques, but it is not always possible to administer a spinal dose despite successful loss of resistance.19 CSEs also have several potential drawbacks, including greater incidence of nonreassuring fetal heart tones (FHT), uterine hyperactivity, maternal pruritis, and neurologic sequelae compared to epidural analgesia.20–23 Furthermore, it has been reported that CSE labor analgesia is more likely to result in prolonged FHT decelerations if there are FHT abnormalities prior to the neuraxial procedure.24 It is our opinion that initiation of labor analgesia via the epidural needle could be advantageous in situations where slightly faster onset of analgesia is desired and CSE may not be possible or is considered a less favorable technique.

There is some concern that dosing prior to catheter placement, such as with a CSE or through the epidural needle, may impair the ability to detect an ineffective catheter in a timely manner and it may not be reliable if a surgical intervention is necessary. There were no epidural catheter replacements in either group during this investigation, but our study was not adequately powered to detect potential delayed recognition of a failed catheter. It should be noted that recent investigations have observed that performing a CSE did not delay the time to recognition of a failed epidural catheter,17,18 though we are not aware of any studies specifically examining potential delayed recognition of a failed catheter after dosing through the epidural needle. The safety of administering a bolus dose through the epidural needle may also be questioned, though no severe complications such as inadvertent IV or IT injection were observed in our investigation or in previous reports.3,5–7 It has been demonstrated that careful aspiration and observation by an experienced anesthesia provider along with incremental medication injection without test dosing may effectively safeguard against IV or IT catheter placement.25 In our experience, incremental dosing through the epidural needle with close patient observation is a safe means of initiating labor analgesia in a timely manner, though it should be recognized that the present investigation was not sufficiently powered to study safety outcomes.

Conclusion

Our comparison of initiating labor analgesia with injection of epidural medication through the needle versus the catheter did not find any significant differences in onset of analgesia from the time of injection, quality of analgesia, or level of sensory blockade. We did not, however, find an increased incidence of side effects or complications when dosing through the epidural needle. Previous reports have also failed to demonstrate complications with this technique.3,5–7 Given the safety and the theoretical benefit, future investigations where analgesic onset is measured from the time of epidural space location rather than from the time of epidural medication injection, or where larger volumes of epidural medication are administered may be worthwhile.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge Vedat O. Yildiz, MS (Center for Biostatistics, Department of Biomedical Informatics, Columbus, OH, USA) for assistance with study design and statistical analysis.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Anim-Somuah M, Smyth RM, Jones L. Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD000331. | ||

Paech MJ. The King Edward Memorial Hospital 1,000 mother survey of methods of pain relief in labour. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1991;19(3):393–399. | ||

Gambling D, Berkowitz J, Farrell TR, Pue A, Shay D. A randomized controlled comparison of epidural analgesia and combined spinal-epidural analgesia in a private practice setting: pain scores during first and second stages of labor and at delivery. Anesth Analg. 2013;116(3):636–643. | ||

Attanasio L, Kozhimannil KB, Jou J, McPherson ME, Camann W. Women’s experiences with neuraxial labor analgesia in the listening to mothers II survey: a content analysis of open-ended responses. Anesth Analg. 2015;121(4):974–980. | ||

Cesur M, Alici HA, Erdem AF, Silbir F, Yuksek MS. Administration of local anesthetic through the epidural needle before catheter insertion improves the quality of anesthesia and reduces catheter related complications. Anesth Analg. 2005;101(5):1501–1505. | ||

Husain FJ, Herman NL, Karuparthy VR, Knape KG, Downing JW. A comparison of catheter vs needle injection of local anesthetic for induction of epidural anesthesia for cesarean section. Int J Obstet Anesth.1997;6(2):101–106. | ||

Yun MJ, Kim YC, Lim YJ, et al. The differential flow of epidural local anaesthetic via needle or catheter: a prospective randomized double-blind study. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2004;32(3):377–382. | ||

Omote K, Namiki A, Iwasaki H. Epidural administration and analgesic spread: comparison of injection with catheters and needles. J Anesth. 1992;6(3):289–293. | ||

Asato F, Goto F. Radiographic findings of unilateral epidural block. Anesth Analg. 1996;83(5):519–522. | ||

Hogan Q. Epidural catheter tip position and distribution of injectate evaluated by computed tomography. Anesthesiology. 1999;90(4):964–970. | ||

Mhyre JM, Greenfield ML, Tsen LC, Polley LS. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials that evaluate strategies to avoid epidural vein cannulation during obstetric epidural catheter placement. Anesth Analg. 2009;108(4):1232–1242. | ||

Okutomi T, Hoka S. Epidural saline solution prior to local anaesthetic produces differential nerve block. Can J Anaesth. 1998;45(11):1091–1093. | ||

Sviggum HP, Yacoubian S, Liu X, Tsen LC. The effect of bupivacaine with fentanyl temperature on initiation and maintenance of labor epidural analgesia: a randomized controlled study. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2015;24(1):15–21. | ||

George RB, Habib AS, Allen TK, Muir HA. Brief report: a randomized controlled trial of Synera versus lidocaine for epidural needle insertion in labouring parturients. Can J Anaesth. 2008;55(3):168–171. | ||

Carvalho B, Fuller A, Brummel C, Cohen SE. Local infiltration of epinephrine-containing lidocaine with bicarbonate reduces superficial bleeding and pain during labor epidural catheter insertion: a randomized trial. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2007;16(2):116–121. | ||

Pan PH, Bogard TD, Owen MD. Incidence and characteristics of failures in obstetric neuraxial analgesia and anesthesia: a retrospective analysis of 19,259 deliveries. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2004;13(4):227–233. | ||

Groden J, Gonzalez-Fiol A, Aaronson J, Sachs A, Smiley R. Catheter failure rates and time course with epidural versus combined spinal-epidural analgesia in labor. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2016;26:4–7. | ||

Booth JM, Pan JC, Ross VH, Russell GB, Harris LC, Pan PH. Combined spinal epidural technique for labor analgesia does not delay recognition of epidural catheter failures: a single-center retrospective cohort survival analysis. Anesthesiology. 2016;125(3):516–524. | ||

Riley ET, Hamilton CL, Ratner EF, Cohen SE. A comparison of the 24-gauge Sprotte and Gertie Marx spinal needles for combined spinal-epidural analgesia during labor. Anesthesiology. 2002;97(3):574–577. | ||

Van de Velde M, Vercauteren M, Vandermeersch E. Fetal heart rate abnormalities after regional analgesia for labor pain: the effect of intrathecal opioids. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2001;26(3):257–262. | ||

Mardirosoff C, Dumont L, Boulvain M, Tramèr MR. Fetal bradycardia due to intrathecal opioids for labour analgesia: a systematic review. BJOG. 2002;109(3):274–281. | ||

Abrão KC, Francisco RP, Miyadahira S, Cicarelli DD, Zugaib M. Elevation of uterine basal tone and fetal heart rate abnormalities after labor analgesia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):41–47. | ||

Cook TM, Counsell D, Wildsmith JA; Royal College of Anaesthetists Third National Audit Project. Major complications of central neuraxial block: report on the Third National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102(2):179–190. | ||

Gaiser RR, McHugh M, Cheek TG, Gutsche BB. Predicting prolonged fetal heart rate deceleration following intrathecal fentanyl/bupivacaine. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2005;14(3):208–211. | ||

Norris MC, Fogel ST, Dalman H, Borrenpohl S, Hoppe W, Riley A. Labor epidural analgesia without an intravascular “test dose”. Anesthesiology.1998;88(6):1495–1501. |

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2017 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.