Back to Journals » Clinical Epidemiology » Volume 10

Initiation of domiciliary care and nursing home admission following first hospitalization of heart failure patients: a nationwide cohort study

Authors Rørth R , Fosbøl EL, Kragholm K , Mogensen UM, Jhund PS , Petrie MC, Torp-Pedersen C, Gislason GH , McMurray JJV, Køber L , Kristensen SL

Received 6 February 2018

Accepted for publication 20 April 2018

Published 2 August 2018 Volume 2018:10 Pages 917—930

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S164795

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Henrik Sørensen

Rasmus Rørth,1 Emil L Fosbøl,1 Kristian Kragholm,2 Ulrik M Mogensen,1,3 Pardeep S Jhund,3 Mark C Petrie,3 Christian Torp-Pedersen,4 Gunnar H Gislason,5 John JV McMurray,3 Lars Køber,1 Søren L Kristensen1,3

1Department of Cardiology, Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; 2Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, Cardiovascular Research Centre, Aalborg University Hospital, Aalborg, Denmark; 3BHF Cardiovascular Research Centre, Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK; 4Department of Health, Science and Technology, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark; 5Department of Cardiology, Gentofte/Herlev University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark

Background: Heart failure (HF) has a major impact on a patient’s quality of life and functional status. This impact may be sufficiently profound to prevent independent living although how often this is the case is unknown. We examined the need for domiciliary assistance and admission to a nursing home following first HF hospitalization.

Methods: In nationwide Danish registries, we identified a cohort of patients discharged alive after a first-time HF hospitalization in the period 2008–2014 who were matched 1:5 with comparison subjects based on age and sex and followed for 5 years.

Results: We included 37,547 patients (69% men) discharged after a first-time HF-hospitalization and 187,735 comparison subjects. The 5-year incidence of initiation of domiciliary care was 24.1% [23.7%–24.6%] among HF patients and 9.2% [9.1%–9.4%] among the comparison cohort and yielded a corresponding adjusted HR of 2.02 [1.96–2.09]. Covariates associated with initiation of domiciliary support included older age (HR 1.08 [1.07–1.08] per 1 year increase in age), living alone (HR 2.09 [2.04–2.15]) and comorbidities. The 5-year incidence of nursing home admission was 3.9% [3.7%–4.0%] among HF patients and 1.7% [1.7%–1.8%] among the comparison cohort and this resulted in an adjusted HR of 1.91 [1.77–2.06]. Covariates associated with nursing home admission included older age (HR 1.10 [1.10–1.11]), living alone (HR 2.15 [2.02–2.28]) and history of stroke (HR 2.71 [2.53–2.90]).

Conclusion: Hospitalization for HF is associated with increased need for domiciliary support and nursing home admissions. Older age, living alone, and comorbidities were associated with higher risk of both outcomes.

Keywords: domiciliary care, nursing home admission, heart failure, epidemiology

Plain language summary

What is already known about this subject? One of the consequences of heart failure may be the inability to carry out activities of daily living and live independently. How often support for patients with heart failure is needed is unknown and it represents an important measure of the personal, family and societal burden of heart failure.

What does this study add? In our nationwide study, we demonstrate a markedly higher risk of future need for domiciliary support and nursing home admission in patients with heart failure, compared to age and sex matched comparison cohorts.

How might this impact on clinical practice? On a personal level, the need for domiciliary support and nursing home admission reflects a loss of autonomy and possible separation from a spouse or family that may cause low self-esteem and potentially depression and other mental health problems. The importance of a disease beyond the usual clinical parameters such as mortality and hospitalization are increasingly recognized in medicine and we believe that domiciliary care and nursing home admission could be used as additional quality metrics for evaluation of the care and disease trajectory of heart failure patients and as such provide a novel perspective on the consequences and impact of heart failure.

Introduction

The prognosis for patients with heart failure (HF) has significantly improved during the last 30 years due to the introduction of beneficial pharmacological treatments and cardiac devices.1 Thus, an increasing part of the population, and particularly elderly people are living longer with HF. However, because HF causes limiting symptoms on exertion and impaired functional status, patients may not be able to carry out activities of daily living and manage independently at home.2 Domiciliary support such as help with shopping, meal preparation, personal care and cleaning and, in extreme cases, institutional care such as admission to a nursing home may be needed. How often these types of support for patients with HF are initiated is unknown yet they reflect an important measure of the personal, family and societal burden of HF.3 At a personal level, loss of autonomy and possible separation from a spouse or family not only causes loss of self-esteem but also unhappiness, loneliness, and potentially depression and other mental health problems. Even the need for domiciliary support in the community can lead to loss of independence, self-esteem, and issues in relation to privacy. To further evaluate these important but under-researched consequences of HF, we conducted a nationwide study in Denmark using cross-linkage of health and administrative registries.

Methods

Data sources

By use of a unique personal identification number assigned to all residents in Denmark, linkage of nationwide registries at an individual level is possible.4 Danish nationwide registries hold information on sociodemographic characteristics, including marital status, as well as information on all hospitalizations since 1978 and all prescribed medication since 1995.5,6 Data on nursing home admissions have been collected since 1994 and data on domiciliary care in the community has been documented since 2008.7 The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency and data are available from Statistics Denmark upon application for researchers located in Denmark. Register-based studies in which individuals cannot be identified do not require ethical approval in Denmark.

Study population and baseline variables

The study population was identified among patients with a first ever HF hospitalization in the period from 2008 to 2014. Patients were required to have a primary or a secondary discharge diagnosis of HF and to be alive at discharge. Patients with a HF hospitalization before 2008 were excluded, as were patients and comparison subjects who had received domiciliary care or were living in a nursing home prior to study inclusion. Each patient entered the study on their date of discharge and was individually matched with five comparison subjects from the general population based on age and sex. All comparison subjects had to be born in the same year and were included from the same date as their matched patient. Five comparison subjects were used to minimize the bias introduced with the matching. Both groups were followed until an outcome of interest occurred, death, for a maximum of 5 years or until end of study (December 31, 2015). Comorbidities were identified by hospital discharge codes in a 10-year period prior to first HF hospitalization. Diabetes mellitus was additionally identified by at least one filled prescription for a glucose lowering drug in the 6 months prior to the first HF hospitalization. Ongoing use of medication was defined by at least one filled prescription of the drug in the preceding 6 months or 7 days after being discharged but was not included in the adjusted Cox regression analyses. To assess whether it was merely the hospitalization in itself and not necessarily the diagnosis of HF which explained the associations with the outcomes of interest, we conducted two sensitivity analyses in an attempt to identify potential detection bias associated with hospitalizations in general: first, we included patients diagnosed with HF in an outpatient clinic, with no previous hospitalization for HF, rather than at time of first hospitalization and compared them to comparison subjects from the general population and, secondly, we used an active comparison group of patients undergoing knee replacement, as these patients are hospitalized and there is a focus on their ability to manage at home after discharge.

Outcome measures

The outcomes of interest were initiation of domiciliary care and admission to a nursing home. Domiciliary care was defined as help given if there are assignments in the home that the citizen can no longer do themselves. In Denmark, domiciliary care covers three main areas: 1) personal care, including bathing, dressing, and eating; 2) practical help such as shopping, cleaning, and doing laundry; and 3) food service.8 Residents in Denmark can freely choose between municipal and private care providers. Therefore, we used information from meetings between residents and municipal staff where the need for domiciliary care is decided, i.e., before the resident decides whether to use private or municipal care providers, limiting the potential bias. Nursing home is defined as an institution where citizens live if they can no longer take care of themselves.

Statistics

Baseline characteristics for HF patients and the comparison cohort were described by use of proportions for categorical variables and medians/quartiles for continuous variables. Cumulative incidence curves for initiation of domiciliary care and nursing home admission, with death as a competing risk, were estimated using the Aalen-Johansen method and differences between patients and the comparison cohort were compared using Gray’s test.9,10 These methods were used in order not to overestimate the risks in the presence of competing risk of death. We also used cause-specific Cox regression to compare the risk of initiation of domiciliary care and nursing home admission between patients and the comparison cohort. The Cox regression analyses were adjusted for age, sex, marital status, calendar year, and comorbidities (ischemic heart disease, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, cancer, chronic kidney disease, COPD, diabetes, and stroke). Adjusted variables were chosen before any analyses were done and were based on clinical relevance and known prognostic importance in HF. Medications for HF were not included in the model to eliminate confounding by indication. The variables sex, age, calendar year, and marital status were tested for interactions with first HF hospitalization in relation to both outcomes and, unless stated otherwise, found absent. Interactions between marital status and first HF hospitalization on both outcomes were furthermore tested separately for men and women. Interactions were significant if they yielded a P-value below 0.01. Log (–log(survival)) curves were used to evaluate the proportional hazard assumption. The assumption of linearity for age was tested by including a variable of age squared.

The SAS statistical software package, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R, version 3.3.2 (R development Core Team) were used for all analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 37,547 patients with a first HF hospitalization between 2008 and 2014 and no prior domiciliary care or nursing home admission was identified. Baseline characteristics of the patients and the comparison cohort are shown in Table 1. HF patients had more comorbidity, higher use of cardiovascular pharmacotherapy, and were more likely to be living alone than their comparison subjects.

Initiation of domiciliary care

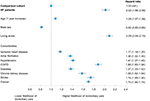

HF patients had a higher 5-year risk of receiving domiciliary care than the comparison cohort (24.1% [23.7%–24.6%] versus 9.2% [9.1%–9.4%]); Figure 1. The competing risk of death was 21.5% [21.1%–21.9%] among HF patients and 6.0% [5.9%–6.1%] in the comparison cohort; Table 2. The median time to initiation of domiciliary care was of 152 days (Q1–Q3 24–623) for HF patients and 646 (Q1–Q3 298–1115) days for the comparison cohort. This yielded an unadjusted HR of 3.44 [3.35–3.53] and an adjusted HR of 2.02 [1.96–2.09], Figure 2. The increased risk associated with being a HF patient did not differ between men and women (men: HR 2.03 [1.93–2.13] and women: HR 2.03 [1.95–2.11]). Factors associated with initiation of domiciliary support included older age (HR 1.08 [1.07–1.08] per 1 year increase in age), living alone (HR 2.09 [2.04–2.15]), and comorbidities; Figure 2. Living alone was associated with a greater need for domiciliary care in both women and men (women: HR=1.98 [1.90–2.06]; men: HR=2.22 [2.15–2.30]; P for interaction=0.03). In sensitivity analyses using patients diagnosed with HF in outpatient clinics, we found that domiciliary care was initiated in a higher proportion of patients than comparison subjects: 18.9% [18.4%–19.3%] versus 9.3% [9.1%–9.4%], respectively; Figure S1. The competing risk of death was higher among HF patients diagnosed in outpatient clinics than in the comparison cohort (14.1% [13.7%–14.5%] versus 8.0 [7.8%–8.1%], respectively). In the adjusted analysis, HF outpatients had a higher risk of receiving domiciliary care than comparison subjects (HR=1.66 [1.58–1.73]). In analyses of HF patients compared with patients undergoing knee replacement we found that domiciliary care was more frequent among HF patients (18.6% [18.2%–19.0%] versus 9.7% [9.4%–10.4%]); Figure S2. In adjusted analyses, HF patients had a higher risk of receiving domiciliary care than patients with knee replacement (HR=2.25 [2.15–2.36]).

| Figure 1 Cumulative incidence of domiciliary care initiation with death as a competing risk among HF patients and the comparison cohort. Abbreviation: HF, heart failure. |

| Figure 2 Multivariable cox regression model of factors associated with initiation of domiciliary care among HF patients and the comparison cohort. Abbreviation: HF, heart failure. |

Nursing home admission

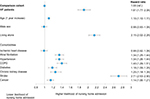

During up to 5 years of follow-up (median time: 1237 days; Q1–Q3: 615–1825 days), the risk of nursing home admission was 3.9% [3.7%–4.0%] among HF patients and 1.7% [1.7%–1.8%] in the comparison cohort; Figure 3. The competing risk of death was almost fourfold higher among HF patients than in the comparison cohort (31.8% [31.3%–32.3%] versus 8.4% [8.3%–8.5%]); Table 2. HF patients had a median time to nursing home admission of 464 days (Q1–Q3 135–997) whereas comparison subjects had a median time of 917 days (Q1–Q3 470–1330). Unadjusted analysis yielded a HR of 2.74 (95% CI 2.58–2.92). In the adjusted analysis, the risk of nursing home admission remained higher among HF patients compared with the comparison cohort (HR 1.91 [1.77–2.06]; Figure 4). Other factors associated with nursing home admission included older age, living alone and all comorbidities, except ischemic heart disease (Figure 4). In women, the HR for nursing home admission for HF patients, compared with comparison subjects, was 2.24 [1.99–2.52], whereas the HR among men was 1.71 [1.55–1.89]. Living alone was associated with a higher risk of nursing home admission both for women and men (women: HR=2.02 [1.83–2.23]; men: HR=2.25 [2.08–2.43]; P for interaction=0.07). In a cohort of patients diagnosed with HF in an outpatient clinic the risk of nursing home admission was higher among HF patients than among comparison subjects (2.7% [2.6%–2.9%] versus 1.4% [1.3%–1.5%]); Figure S3. The competing risk of death was 21.0% [20.5%–21.4%] among HF patients and 10.0 [9.8%–10.2%] in the comparison cohort. Adjusted analyses of HF outpatients, compared with comparison subjects, yielded a HR of 1.58 [1.41–1.76] for nursing home admission. When comparing HF patients, with patients undergoing knee replacement we found that HF patients had a higher risk of nursing home admission (2.2% [2.1%–2.4%] versus 0.6% [0.6%–0.7%]); Figure S4. This increased risk for patients with HF persisted in adjusted analyses (HR=4.45 [3.79–5.22]).

| Figure 3 Cumulative incidence of nursing home admission with death as a competing risk among HF patients and the comparison cohort. Abbreviation: HF, heart failure. |

| Figure 4 Multivariable cox regression model of factors associated with nursing home admission among HF patients and the comparison cohort. Abbreviation: HF, heart failure. |

Discussion

We found that HF patients were twice as likely as a comparison cohort from the general population to receive domiciliary care or be admitted to a nursing home. Although the absolute rate of nursing home admission was relatively low (approximately 1 in 25 patients admitted over 5 years), around 1 in 4 patients received domiciliary support, highlighting the likely impact of HF on functional status and the ability to live independently. Factors associated with nursing home admission included older age, living alone, and comorbidities, particularly prior stroke. These factors were also associated with provision of domiciliary care, along with female sex.

Living with HF is characterized by symptoms of exertion, principally breathlessness and fatigue, which tend to worsen over time and may significantly limit functional capacity and the ability to carry out the activities of daily living. Disease progression also leads to hospitalization because of worsening symptoms and premature death. The decision to initiate domiciliary care, or to admit a patient to a nursing home, is based, in part, on an evaluation of the individual’s functional status, which may depend solely on the severity of HF but also on the impact of other illnesses. In this respect, it was notable that comorbidity was associated with need for domiciliary and nursing home care, suggesting that the cumulative burden of disease is important. Other factors such as cognitive function, mental health, and support from a spouse or family must also be considered. Here it was notable that living alone was also associated with the need for domiciliary and nursing home care, emphasizing the key role of spousal support for patients with HF. Our finding that men were less likely to receive domiciliary care, irrespective of having HF or not, might have a related explanation in that more men are likely to have a healthy spouse to look after them as women live longer than men. Women with HF also live longer than men with HF and women have more symptoms, which means they may be more likely than men to need domiciliary care or nursing home admission.11–13

Although we showed a doubling of the need for domiciliary and nursing home care among HF patients relative to a comparison cohort from the general population, it is important to keep in mind that the absolute risk of nursing home admission was very low and that death was a major competing risk. The uneven distribution of the competing risk of death between HF patients and the comparison cohort might have led to an underestimation of the real difference between the two groups. However, the absolute risk of domiciliary care initiation was considerable and demonstrates in a new way the burden of HF on patients and society.

One potential concern about this interpretation might be that the occurrence of hospital admission may have unmasked patients’ inability to cope at home or that some other factor related to hospitalization, rather than HF per se, accounted for our findings. However, in our sensitivity analyses, we found that patients diagnosed with HF in outpatient clinics, were more likely than comparison subjects to need domiciliary and nursing home care (Figures S1 and S3), and similarly when we compared HF patients with patients hospitalized in order to undergo knee replacement, HF patients had a higher risk of subsequent need for domiciliary and nursing home care (Figures S2 and S4). However, to undergo knee replacement surgery, patients are required to have a certain level of physical fitness which may have confounded these analyses.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of our study lies in the completeness of data, i.e., except for those who emigrated from Denmark (less than 1% of the study population) we have complete follow-up on all included persons. We have a nationwide unselected cohort of patients with a first hospitalization for HF and a comparison cohort followed in real-life settings. Our study has several limitations. The observational nature of the study means that we report associations that may not be causal. The influence of unmeasured clinical parameters, including important comorbidities such as dementia, and other unidentified confounders cannot be excluded and thus our comparison cohorts might differ in aspects not accounted for in our analyses. We did not have access to some clinically important information on patients such as left ventricular function and New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class. Data on hours and kind of domiciliary care as well as time in nursing home is not sufficiently registered and thus not available to study. This means that the outcome of need for care may cover a wide spectrum of care needs. Information on all use of private care services might not be captured in our analyses and could potentially bias our results. Our findings were based on the Danish health care and social systems and therefore may not be applicable to other countries.

Conclusion

Patients with a first-ever hospitalization for HF had a significantly higher risk of initiation of domiciliary care and nursing home admission than a comparison cohort from the general population. Older age, living alone, and comorbidities were associated with a higher risk of these types of care. Domiciliary care and nursing home admission could be additional quality metrics for the care of HF patients and as such provide a novel perspective on the consequences and impact of HF.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Sacks CA, Jarcho JA, Curfman GD. Paradigm shifts in heart-failure therapy – a timeline. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):989–991.

Dunlay SM, Manemann SM, Chamberlain AM, et al. Activities of daily living and outcomes in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8(2):261–267.

Wenger NK. Quality of life: can it and should it be assessed in patients with heart failure? Cardiology. 1989;76:391–398.

Thygesen LC, Daasnes C, Thaulow I, Brønnum-Hansen H. Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7 Suppl):12–16.

Hjollund NH, Larsen FB, Andersen JH. Register-based follow-up of social benefits and other transfer payments: accuracy and degree of completeness in a Danish interdepartmental administrative database compared with a population-based survey. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35(5):497–502.

Schmidt M, Schmidt SA, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449–490.

Jacobsen A. Imputering af borgere på plejehjem/-bolig [Imputation of citizens living in nursing homes/supported accomodation]. Danmarks Stat [Statistics Denmark].[in Danish]. www.dst.dk/ext/velfaerd/Imputering. 2014.

Aeldresagen [webpage on the Internet]. Available from: https://www.aeldresagen.dk/viden-og-raadgivning/hjaelp-og-stoette/hjemmehjaelp. Accessed January, 2018.

Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Statist. 1988;16(3):1141–1154.

Aalen OO, Johansen S. An empirical transition matrix for non-homogeneous Markov chains based on censored observations. Scand J Statist. 1978;5(3):141–150.

Lund LH, Mancini D. Heart failure in women. Med Clin North Am. 2004;88:1321–1345, xii.

Gottlieb SS, Khatta M, Friedmann E, et al. The influence of age, gender, and race on the prevalence of depression in heart failure patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(9):1542–1549.

Levy D, Kenchaiah S, Larson MG, et al. Long-term trends in the incidence of and survival with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1397–1402.

Supplementary materials

| Figure S2 Cumulative incidence of domiciliary care initiation with death as a competing risk among HF patients compared with patients undergoing knee replacement. Abbreviation: HF, heart failure. |

| Figure S4 Cumulative incidence of nursing home admission with death as a competing risk among HF patients compared with patients undergoing knee replacement. Abbreviation: HF, heart failure. |

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2018 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.