Back to Journals » Cancer Management and Research » Volume 13

Information Needs of Breast Cancer Patients Attending Care at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital: A Descriptive Study

Authors Legese B, Addissie A, Gizaw M , Tigneh W, Yilma T

Received 17 June 2020

Accepted for publication 4 December 2020

Published 12 January 2021 Volume 2021:13 Pages 277—286

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S264526

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Antonella D'Anneo

Birhan Legese,1 Adamu Addissie,2 Muluken Gizaw,2 Wondemagegnhu Tigneh,3 Tesfa Yilma4

1Madawalabu University, College of Health Sciences, Department of Public Health, Goba, Ethiopia; 2Addis Ababa University, College of Health Sciences, School of Public Health, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 3Addis Ababa University, School of Medicine, Department of Oncology, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 4Ambo University, College of Health Sciences, Department of Medicine, Ambo, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Birhan Legese

Department of Public Health, Madawalabu University, College of Health Sciences, Goba, Ethiopia

Tel +251910796908

Email [email protected]

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to assess the information needs of women with breast cancer attending care at a major hospital in Ethiopia. It also aimed at describing the association of information needs with sociodemographic and clinical variables, preferred sources of information, and time to have it.

Patients and Methods: A hospital-based cross-sectional study was conducted on 375 women with breast cancer at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital. Data were collected by interview and Toronto information needs questionnaire for breast cancer which contains 52 items categorized under five domains was pretested, adopted, and used to address the information needs of patients. One way ANOVA was done to get an association of sociodemographic and clinical variables with information needs. All statistical analysis was performed using STATA (Version 14), and statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

Results: The total mean score for overall information needs among breast cancer patients was 238.7 (22.5) with a range scale of 156– 260. Among the five subscales information on disease and information on treatment were the most highly needed areas with a mean percentage of 94.8 and 93.7, respectively; and 254 (67%) of them preferred the information to come from health professionals. Diagnosing as stage IV (p=0.0005) and urban residence (0.02) was associated with less and high information needs, respectively.

Conclusion: The information needs of breast cancer patients were high. Determining what the patient’s needs are an important aspect of providing health care especially in cancer care. The healthcare system should include a way of information provision system for breast cancer patients based on their needs.

Keywords: breast cancer, information needs, Ethiopia

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer case among females in the world accounting for 1 in 4 cancer cases and is the most frequently diagnosed as well as the leading cause of death in many countries including the least developed countries.1,2

First data from a population-based cancer registry in Ethiopia showed that cancers of the breast are the first cancer cases in women, accounting for 31.5%.3 Most cancer is usually diagnosed in advanced stages at presentation and most of the patients were young with poor treatment outcomes.4,5

Having breast cancer is a traumatic experience for both patients and their families and is accompanied by a series of dramatic changes in life including disease-related physical pain or fatigue, and psychosocial problems. In addition, women with breast cancer experience specific emotional problems such as issues of fertility and child bearing; changes in body image related to treatments like losing hair and removed breast.6,7 This complex nature of the illness and its psychosocial impact along with the adverse effects of the treatment make them demand to develop a genuine relationship with health professionals and requires them to decide tough decision regarding their treatment, learn about their disease and coping mechanism.8,9 Consequently, they will encounter information needs during their disease and its management trajectory.8

Researches done in different countries of the world showed that patients with cancer have high information needs on a wide range of factors for many reasons.10–13 For its positive impact on their feelings and emotion, to control and understand their situation, to take an active part in their care, and to cope with their condition and fears were among the reasons for needing information as reported by patients.14 Moreover, ambiguities, uncertainties, fears, and anxiety came from lack of awareness or having insufficient information about the nature of disease, treatment, and prognosis could be the reason to have high information need.15,16 The commonest types of information needs of (breast) cancer patients comprised the disease aspect, treatment option, treatment side effects, physical pain and its management. It also contains information on sexuality, daily life and activities, emotional support, and others.12,13,15,17,18 In general, Prognosis, diagnosis, and treatment options were the top three cancer patients’ priorities of information according to a systematic review done by Tariman et al.10 Patients need for information persists throughout their journey from diagnosis to follow-up regardless of having undergone or finished active therapy.11–13,19 In spite of their high needs, cancer patients continuously reported high unmet needs of information and dissatisfaction with the availability or provision of information.20 A previous systematic review, for example, showed that there was a wide range of unmet needs existed among cancer patients including information needs on benefit and adverse effects of treatment modalities21 and limited health literacy, type of treatment, age, and language difference might be among factors associated with high unmet needs of information.21,22

Cancer patients mentioned different sources of information that they need such as leaflet, internet, and other non-medical personnel. But, the preferred sources for most of the patients were health professionals,12,23 and these findings emphasize the key role that healthcare providers could play in meeting the information needs of patients.12,24 A study done by Alananzeh et al, for instance, showed that patients wanted to have detailed information based on their situation about the state of the disease, treatment process, and the recovery journey preferably from their doctor. They also reported that they had less trust for the information that originates from the internet, and given written information about their disease from health providers was too scientific for them to understand.25

Different patients are likely to have different priorities in information needs according to their socio-demographic factors and clinical background. A study that was done on Chinese breast cancer patients, for example, indicated that patient’s religious beliefs, whether living alone or not, educational level, and time since diagnosis influenced their preferences for information needs.26 A systematic review by Tariman et al also showed that information connected to sexuality was the focus of younger patients, while older adults wanted information connected to self-care.10 Moreover, time since diagnosis, occupation, and physical condition were factors associated with information seeking and needs according to an original study done by Sainio et al.14 Additionally, a meta-analysis by Ankem also showed that age was significantly associated with information that younger cancer patients wanted more information compared with older patients.27

Understanding and meeting the information needs of breast cancer patients are critical in improving the quality of life of patients. It also lowers their levels of depression and anxiety,23,28 improves an individual’s coping and self-care mechanisms29 by making them active participants in the process of their healthcare management.22,27 It is also important to consider it as one of their rights that they deserve receiving appropriate information on their own illness and its subsequent treatment.16,30

Despite a gradual recognition as one of the public health concerns, cancer in Ethiopia continued to get low public health attention because of other health problems like communicable diseases.31 Studies reported that cancer in general and breast cancer in particular should be a public health concern for its high prevalence and most commonly diagnosed in young patients at late stage of the disease which was due to multiple factors related to an individual awareness and misconception about the disease and its treatment as well as factors related healthcare system such as inaccessible and poor quality health care32. The government drafted a five-year national cancer control plan for the period of 2016–2020 to reduce the burden of cancer through prevention, curing, or prolonging the life of cancer patients and ensuring the best possible quality of life for cancer survivors.33 However, researches showed that cancer patients in Ethiopia were continuously reporting a low level of quality of life, a high level of symptoms, and a large number of unmet needs like emotional support, respected care, financial support, and pain relief. The majority of the patients also reported that they were not satisfied with the current availability and provision of cancer-related information,34,35 and one in four breast cancer patients were depressed. Poor social support, severe pain, and type of treatment were among the factors that were associated with depression.36 Furthermore, previous researches revealed that the relation of breast cancer with body image is one of the reasons for patients to experience a worsening problem and to have a poor quality of life.6,7

Because treatment of breast cancer is complex and prolonged, it needs active involvement of patients themselves. It is known that treatment for breast cancer is prolonged and complex, it needs the active involvement of the patients themselves. Studies also indicated that patients with cancer need information to decide on their treatment, to prepare for the future, and to help them cope with their disease. Well informed and satisfied cancer patients are able to adhere to their treatment, cope with the illness, and have a better quality of life. Thus, the appropriate information should be given to them based on their needs and is one of the methods for quality care delivery in cancer care services. Hence, knowing the position of women towards receiving this information is necessary to give them tailored information. In Ethiopia, research regarding the information needs of breast cancer patients is limited. Hence, this study was intended to fill this gap.

Patients and Methods

Study Setting and Design

A hospital-based cross-sectional study was used from March to May 2017 at the oncology department of Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital (TASH). TASH is located in the capital city of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. It is the largest and maybe the only referral hospital serving people who come from all parts of the country. It has one CT and one MRI scanner. Treatments offered at its cancer center include anticancer drugs, surgery, and it is the only hospital to give radiotherapy in the country.

Sample Size Determination and Sampling Technique

The sample size was calculated using the formula for a single population proportion (z2p (1-p)/d2) taking proportion (p) of patients on chemotherapy who want information on chemotherapy and their management (63%)35 and 95% level of confidence. After adding a 10% none respondent rate, the final sample size becomes 394. The eligibility criteria were all pathologically confirmed breast cancer patients from inpatient and outpatient departments, who are above 18 years of age and who are on treatment in the study hospital during data collection time.

Patients who were not able to communicate due to severe physical fatigue or/and language barrier were excluded from the study.

Variables

Dependent variables

Information needs among female breast cancer patients and preferred source of information.

Independent Variables

Socio-demographic (Age, marital status, educational status, religion, occupation, residence), clinical factors (time since diagnosis, stage of the diseases, and type of therapy)

Data Collection Procedures

A structured questionnaire from literature was used for the assessment of socio-demographic data of the patients and clinical information. For the assessment of information needs, a pretested Toronto informational needs questionnaire for breast cancer (TINQ-BC) was used to measure the information needs of breast cancer patients.

Three skilled nurses for data collection and one supervisor were selected with previous experience in data collection and training was given on the data administration and collection techniques. The trained nurses administered the questionnaire via an interview for patients who gave their informed consent to participate in the study. Clinical variables were collected from their medical records and oncologist was consulted to clarify some medical terms in collecting data like the stage. Data from the patients themselves and from their medical card were collected after patients gave their informed consent.

The Toronto Informational Needs Questionnaire of Breast Cancer (TINQ-BC)

TINQ-BC was developed to assess specific informational needs of breast cancer populations, such as patients being treated by surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy.37–39 It was widely used in the world including African countries like Zambia40 and Egypt41,42 and it has the potential to assess the information needs of women with breast cancer on an international basis.43

The development and initial testing of the instrument was outlined by Galloway et al (1997) “To elicit women’s perception of their information needs related to their experience of breast cancer despite the ceiling effect of the instrument”.39 It was even applied effectively to other cancer patients such as prostate cancer.44

TINQ-BC contains 52 item scales, measuring the following five subscales of information needs, namely, diseases, treatment, physical, investigative tests, and psychosocial with a minimum score of 52 and a maximum of 260, the mean score to represent higher information needs is 200 and above.39

The Five Subscales of TINQ-BC

Treatment (16 Items)

Assess information needs about various treatments, how they work, performed, sensations that may be experienced, and possible side effects. Disease (9 items): assess information needs about nature, process, and prognosis of the disease.

Investigative Tests (8 Items)

Assess information needs about procedures used to assess the extent of disease, how, why they are done, and sensations that may be expected.

Physical (11 Items)

Assess information needs about the preventive, restorative, and maintenance care that may be needed as a result of the disease and treatments.

Psychosocial (8 Items)

Assess information needs about how to handle the patients’ or their families’ feelings.

Data Management and Analysis

To maintain data quality, the tool (TINQ-BC) was translated into Amharic and the Amharic version was again translated back to English by different individuals including language expert to check for consistency and equivalence of meaning. The translated Amharic version of the questionnaire was pre-tested on 20 patients prior to the actual data and simplicity, accuracy of responses, language clarity, and appropriateness of the tool was checked. Based on the finding of the pretest, the necessary corrections regarding language clarity and ease of administration were incorporated into the study tool. The investigators and language experts then found the tool to be applicable for the study population via interview. Hence, the tool was adopted to use it in this study for measuring the information needs of women with breast cancer after minor modification.

The data collection instruments were coded and data were checked and entered using EpiData version 3.1 and all statistical analysis was performed using STATA (Version 14), descriptive statistics were used to compute mean, frequency and percentage whereas one way ANOVA was used to examine if there was a mean difference between dependent and independent variables among the groups. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

Ethical Consideration

For maximum protection of the rights of patients, this study was conducted in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki and National research ethics guidelines. Permission to undertake the study was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of Addis Ababa University College of Health Sciences, School of public health. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study, the possible time the study could take, the confidentiality of the information, and the right not to participate or withdraw at any time. Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study prior to the beginning of data collection. Data were treated in strict confidentiality and there was no patient name in any form to protect patient privacy.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

The final sample size for obtaining data for this study was 394 and 375 of them were willing to participate making the response rate to be 95.17%. The majority (80.53%) of participants in the study were between the age of 20 and 51 with the median age of 40. Those who follow Orthodox Christianity were (70.70%). Urban dwellers were 303 (80.80%), and Addis Ababa is the living place for 167 (44.50%) of them. High school was the most frequently reported (29.90%) level of education. A large portion 280 (74.70%) of the women indicated that they are married and over half of them, ie, 212 (56.50) were housewives.

Clinical Characteristics of the Participants

The majority of the patients 160 (42.90%) were diagnosed as stage III and only below 5% of them were diagnosed as early as stage I. As high as 70% of the women had diagnosed within a period of 2 years. Most of the participants 244 (65.10%) who were on chemotherapy were also underwent surgery or took radiation treatments, 22.40% were on hormonal therapy. Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of patients.

|

Table 1 Clinical Characteristics of Breast Cancer Patients Attending Care at TASH, Addis Ababa Ethiopia, March–May 2017 (n=375) |

Descriptive Statistics of Information Needs Among Breast Cancer Patients

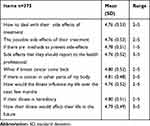

The TINQ-BC was used to assess the information needs of breast cancer patients using 52 items and 5 subscales. Mean score 200 and above for overall, 4 and above for subscale and single item rated as high information needs. Mean score above 4.75 was rated as extremely important for a single item.39

In this study, the total mean score for overall information needs among breast cancer patients was 238.7 (22.50) with a range scale of 156–260.

About 9 items scored mean above 4.75 (Table 2) including “If there is cancer anywhere else in my body” (M=4.81 with a scale of 2–5); “If the breast cancer will come back” (M=4.80 with a scale of 2–5); and “If there are ways to prevent treatment side effects” (M=4.79 with scale of 1–5).

|

Table 2 Information Needs Among Breast Cancer Patients Attending Care at TASH, Addis Ababa Ethiopia, March–May 2017. Items with Highest Score (>4.75) |

The minimum mean score, when compared to others, was “What to do if I become concerned about dying” (M=4.05 with scale 1–5) and “Where I can get help if I have problems feeling as attractive as I did before” (M=4.1 with a scale of 1–5).

There are five subscales that were scored from the Toronto information needs questionnaire of breast cancer. Because of unequal numbers of items in each subscale standardized mean score or percentage was used to identify the areas of highest information need between subscales.

Information Needs on Treatment

This subscale has 16 items to assess information needs about various cancer treatments, how they work, performed, sensations that may be experienced, and possible side effects.39 The overall mean of this subscale was (M=75 on a scale from 48 to 80) with standardized mean of 4.68 which rated between “very important to extremely important” with a mean percentage of 93.70%.

Information Needs on Disease

The disease subscale has 9 items to assess information need about the nature, process, and prognosis of the disease.39 In this study, it was rated between “very important and extremely important” with a standardized mean of 4.73 (M=42.6 on a scale of 23–45) and a mean percentage of 94.80%.

Information Needs on Investigative Test

This is an 8 item subscale to assess information needs about procedures used to assess the extent of disease, how, why they are done, and feelings that may be experienced.39 Information needs on investigative tests for this study were rated between “very important to extremely important” with mean of 4.50 (M=36 on a scale from 21 to 40) and percentage of 90.

Information Needs on Physical

The physical information needs subscale contains needs about the preventive, restorative, and maintenance care that may be needed as a result of the disease and treatments. It has 11 items.39 For the physical subscale, the standardized mean and its percentage were 4.59 and 90.80 (M=50.5 on a scale from 33 to 55), respectively. It was rated between “very important to extremely important”.

Information Needs on Psychosocial

Information needs about how to handle the patients’ or their families’ feelings assessed by an 8 item subscale for psychosocial information needs.39

It was itemized as “very important” (M=34.5 on a scale of 16 to 40) with a mean percentage of 88 and the standardized mean of this subscale was 4.3.

Relationship of Information Needs with Sociodemographic and Clinical Variables

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted between the mean score of information needs and demographic and clinical variables to detect if there significant differences in mean score of information needs among groups as a whole, and ratio mean square values (F) along with degrees of freedom and p value were used to report as the following.

Thus, the only differences between means revealed by ANOVA were living locations and stage at diagnosis. According to ANOVA, there was a significant mean difference of information needs among different living locations at the value of p<0.05 for urban, semi-urban and rural area [(F=2, 372) = 3.55, p= 0.02] and among disease stage [(F=3, 371)= 6.03, p=0.0005]. Pairwise comparison of means was performed using Tukey HSD test to determine which group is significantly different from others. It showed that mean score for urban residents was significantly different or higher (M=240.21, S.D.=21.61) than rural. But, the mean of semi-urban (M=232.75, S.D.=26.6) was not significantly different from urban and rural. Similarly, the mean score for information among stage IV patients (M=230.12, S.D.=23.1) was significantly different (lower) than stage II and III. But, the mean score (M=235.35, S.D.=26.6) of stage I was not significantly different from other.

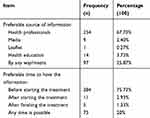

Preferable Source and Time to Have Information

Regarding the preferable source of information, 254 (67%) of participants want health professionals, ie, Doctors and nurses to be their primary source of information, whereas, 97 (25.87%) of them want to have it by any means as shown in Table 3. Similarly, 284 (75.73%) of the participants mentioned that the appropriate time to have information is before starting the treatment and 75 (20%) of them mentioned having information at any time is the right time.

|

Table 3 Preferable Source and Time of Information Among Breast Cancer Patients Attending Care at TASH Addis Ababa Ethiopia, March–May 2017 (n=375) |

Discussion

It is common for breast cancer patients to experience physical, social, sexual, and psychological (including anxiety and depression) problems.6,7,8,7,45 Studies showed that having timely and appropriate information helps breast cancer patients to involve in an informed decision of their treatment process, learn about the disease, and control their life and coping mechanism. It also improves their quality of life and lowers their anxiety and depression. Thus, understanding and meeting the information needs of breast cancer patients are critical in patient-centered and quality cancer care.22,23,27–29 Despite a report of poor quality of life, high depression state, and unmet information needs,34–36 there is limited evidence in Ethiopia that showed the information needs of breast cancer patients. But it is known that identification of the level of information needs in breast cancer patients receiving care help to give tailored cancer quality care. This study assessed the information needs of breast cancer patients using TINQ-BC. Additionally, associated factors, preferred sources, and time were also assessed.

The information needs of breast cancer patients in this study was high which is consistent with many previous studies.10–13,19,26 The total mean for overall information needs was 238.7 (22.50) with a mean score of 4.59 which was rated as high need. This is higher than the finding of Yi et al43 which brought a mean total score of 203 (mean score= 3.91); Graydon et al39 which reported a mean total score of 214 (mean score=4.11) and Harrison et al found a mean total score of 207 (mean score=3.98).37 The difference might be due to the low health literacy level of patients and limited access to information. It could also be for the fact that health institutions are the only sources of health information for most patients in Ethiopia.

Breast cancer patients want different types of information including disease features, treatment option and side effects, sexuality, psychosocial, and prognosis.12,13,15–17,26

In this study, information on disease was the highest needed area followed by treatment which is consistent with many previous findings that used the same tool.13,17,37,39,43 Similarly, the only study in our country on the information needs among all types of cancer patients by Mekuria et al also came up with the finding that the majority of patients need information on disease followed by treatment.45 However, Mamushi et al,40 Sayed et al,42 and Mohamed et al41 found that the most needed area was information on investigative tests, treatment, and physical, respectively. “If there is cancer anywhere else in my body”, “if the breast cancer will come back” and “if my illness is hereditary” were the top 3 items with the highest mean score from disease-related questions. The finding of the first two items is congruent with previous studies,13,37,39,40 and this could show that breast cancer patients are more concerned and worried about the future (metastasize and recurrence of disease). In addition, breast cancer patients had high information if the illness is hereditary and this could indicate those patients may worry about the future of their family especially offspring. This impression could be supported by research done on the Psychosocial impact of breast cancer in Omani female patients by Al-Azri et al that the majority of patients were concerned about the possibility of their daughters inheriting the disease.46 In the treatment domain, the possible side effects, how to deal with, how to report, and ways of prevention were areas of highest information need. This finding is expected which highlights the importance of determining concerns on treatment effects. Compared with other domains, information need on psychosocial was the lowest needed area which is similar with other previous studies.13,37,39,40 But the value was still higher that may not mean do not need it, rather their priority may be shifted to other areas due to the possibility of high unmet needs on topics that they perceived as urgent.

Some sociodemographic factors like age, living location, education, and clinical factors like the stage and time since diagnosis may influence the level of information needs among breast cancer patients. This study failed to detect significant differences unlike other studies that found a significant difference in information needs among age group,10,11,27,39,41 educational level, and treatment type.11,41 The difference in this study may be due to the high proportion of young age and similar educational level that the majority of the participants were below the age of 50 and at high school and elementary level.

There was a significant (p<0.05) difference in information needs based on their living location and disease stage. Breast cancer patients living in the urban areas had more information needs compared with those who live in a rural area. This is similar to the previous study by Mohamed et al.41 The reason for this could be due to that patients living in urban area are exposed to a certain access like technologies or other sources compared with rural area so that they could understand having information is necessary and would help them. Association between disease stage and information needs is inconsistent in different researches. For instance, a study done by Yi et al and Seah et al found a significant difference in information needs among patients in different disease stages.43,47 On the other hand, Ankem et al found that there was no association between information needs and cancer stage.27 In this study, we found that patients with an advanced stage of cancer (stage IV) showed less information needs compared with other stages. This is different from a previous study done by Seah et al that reported patients with advanced breast cancer had high information needs.47 These significant differences of information between these groups could be explained by the fact that breast cancer patients with an advanced stage of cancer are at high risk for depression45 that they experience depressive emotional feelings like loss of interest, emptiness, and hopelessness. Another explanation could be that wanting less or avoiding any information related to their situation could be one way of their coping style. Avoidance of various factors including social and behavioral disengagement is one of the coping strategies that breast cancer patients use.48,49

Participants of this study also chose their preferred sources of information and most (67.7%) of them would like to have information that comes through health professionals. This is similar to the study of Mekuria et al that doctors and nurses were the preferred sources of cancer patients35 and other studies also showed that the preferred source of information for breast cancer patients was health professionals.12,23 This finding is expected in a country like Ethiopia where other options such as the internet and other media are limited even if they try to look for another source. As high as 25.7% of patients also mentioned that they are ready to get information by any means that may highlight all they want is information.

The appropriate time to have information cited by most (75.73%) was before starting the treatment and any time was cited by 20% of them and this finding is similar to a review done by Li et al that found most patients want information before treatment to get time to think and make an informed decision.17

The practical implication of the findings of this study is highlighting the necessity of understanding and integrating the expressed needs of breast cancer patients in the delivery of cancer care in order to improve the quality of care. To deliver integrated and comprehensive care, cancer care professionals should acknowledge that cancer patients could suffer from various types of problems and could be in need of information during their illness trajectory.23,28 In this study, we found that extremely high information needs existed among breast cancer patients, especially concerning about the possibility of cancer spreading to other parts of the body, heritability, recurrence, and treatment side effect preferably before treatment.

Thus, the cancer treatment center should take these concerns into consideration to satisfy the needs of patients by informing them about the state and behavior of their illness, and about the process of its management before the starting of the treatment. Appreciating giving information based on patients’ needs could help patients in improving their quality of life, adhering to their treatment, coping mechanism and anxiety and depression is important.

In addition, the preferred sources of information for most patients were health professionals. Health professionals should understand this and should play an important role in providing women with the necessary time and resources to assist them in making informed and satisfying decisions. However, according to a research, satisfaction with the information given depends on the quality of the relationship between professionals who give the information and patients. Therefore, establishments of professional-patient relationships should be taken into consideration during practice for useful, understandable, quick, efficient, and continuous information exchange.9

Coping strategy or attitude is one of the factors which determine patients’ preferences for information. At some point in their illness path, some patients may prefer to avoid disease-related information.50 In the current study, stage IV showed less information needs compared with others. This could be a sign of psychological morbidity and poor quality of life because studies showed that women with advanced breast cancer are prone to psychological distress and poor quality of life.45 The level of distress and poor quality of life are associated with avoidant coping strategy.51 Hence, great attention should be given to this group of patients that screening, understanding, and addressing the possible factors that are associated with their low information needs during their treatment period is needed.

Limitations of This Study

This study contains limitations in that it was a cross-sectional study preventing a clear separation among people in different illness periods. Thus, it may hinder the possibility of detecting changes in information needs of breast cancer patients throughout the disease progression from the first detection of the case to the final outcome due to the fact that it is not a longitudinal study.

It was also a single-institution study and may, therefore, not represent the reality of patients of other institutions or those who stayed at home. So, generalization is difficult.

Conclusion

Patients attending care at TASH presented higher overall information needs. They reported high needs for information on each domain and on disease recurrence, heritability, and treatment side effect. Breast cancer patients should get information about their illness along with the full range of treatment options and side effects if possible by health professionals. There should be enough discussion and conversation time with the patient to accommodate the patient’s feelings, desires, and needs to provide tailored information and care.

Patients diagnosed as stage IV has less information needs when compared to others. Patients living in urban areas have more needs for information than patients living in a rural area. Thus, evaluating and addressing the possible reasons for having less information needs is necessary.

Acknowledgments

This research was done for academic purpose with the fund from Addis Ababa University. The full thesis was uploaded and it is available online.52

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest for this work.

References

1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi:10.3322/caac.21492

2. Organization. WH. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. Geneva, Switzerland; 2014.

3. Timotewos G, Solomon A, Mathewos A, et al. First data from a population based cancer registry in Ethiopia. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;53:93–98. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2018.01.008

4. Sm A. Trends of breast cancer in Ethiopia. Int J Cancer Res Mol Mech. 2016;2(1):1.

5. Dagne S, Abate SM, Tigeneh W, Engidawork E. Assessment of breast cancer treatment outcome at tikur anbessa specialized hospital adult oncology unit, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Eur J Oncol Pharm. 2019;2(2):e13. doi:10.1097/OP9.0000000000000013

6. Iddrisu M, Aziato L, Dedey F. Psychological and physical effects of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment on young Ghanaian women: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):353. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02760-4

7. Ghaemi SZKZ, Tahmasebi S, Akrami M, Heydari ST. Conflicts women with breast cancer face with: a qualitative study. Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(1):27–36. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_272_18

8. Chua GP, Tan HK, Gandhi M. What information do cancer patients want and how well are their needs being met? Ecancermedicalscience. 2018;12:873. doi:10.3332/ecancer.2018.873

9. Bilodeau K, Dubois S, Pepin J. Interprofessional patient-centred practice in oncology teams: utopia or reality? J Interprof Care. 2015;29(2):106–112. doi:10.3109/13561820.2014.942838

10. Tariman JD, Doorenbos A, Schepp KG, Singhal S, Berry DL. Information needs priorities in patients diagnosed with cancer: a systematic review. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2014;5(2):115–122.

11. Mistry A, Wilson S, Priestman T, Damery S, Haque M. How do the information needs of cancer patients differ at different stages of the cancer journey? A cross sectional survey. JRSM Short Rep. 2010;1(4):30.

12. Rutten LJ, Arora NK, Bakos AD, Aziz N, Rowland J. Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: a systematic review of research (1980–2003). Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57(3):250–261. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2004.06.006

13. Sheehy EM, Lehane E, Quinn E, Livingstone V, Redmond HP, Corrigan MA. Information needs of patients with breast cancer at years one, three, and five after diagnosis. Clin Breast Cancer. 2018;18(6):e1269–e1275. doi:10.1016/j.clbc.2018.06.007

14. Carita Sainio C, Eriksson E. Keeping cancer patients informed: a challenge for nursing. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2003;7(1):39–49. doi:10.1054/ejon.2002.0218

15. Khoshnood Z, Dehghan M, Iranmanesh S, Rayyani M. Informational needs of patients with cancer: a qualitative content analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019;20(2):557–562. doi:10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.2.557

16. Kimiafar K, Sarbaz M, Shahid Sales S, Esmaeili M, Javame Ghazvini Z. Breast cancer patients’ information needs and information-seeking behavior in a developing country. Breast. 2016;28:156–160. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2016.05.011

17. Li J, Luo X, Cao Q, Lin Y, Xu Y, Li Q. Communication needs of cancer patients and/or caregivers: a critical literature review. J Oncol. 2020;2020:7432849. doi:10.1155/2020/7432849

18. Holzapfel LCHJT. Identification of the information needs concerning the physical symptoms of patients with breast cancer. F W. 2016;11:1.

19. Shea-Budgell MA, Kostaras X, Myhill KP, Hagen NA. Information needs and sources of information for patients during cancer follow-up. Current Oncol. 2014;21(4):165–173. doi:10.3747/co.21.1932

20. Halbach SM, Ernstmann N, Kowalski C, et al. Unmet information needs and limited health literacy in newly diagnosed breast cancer patients over the course of cancer treatment. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(9):1511–1518. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2016.06.028

21. Wang T, Molassiotis A, Chung BPM, Tan JY. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17(1):96. doi:10.1186/s12904-018-0346-9

22. Kowalski C, Lee SY, Ansmann L

23. Kugbey N, Meyer-Weitz A, Oppong Asante K. Access to health information, health literacy and health-related quality of life among women living with breast cancer: depression and anxiety as mediators. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(7):1357–1363. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2019.02.014

24. McWilliam CL, Brown JB, Stewart M. Breast cancer patients’ experiences of patient–doctor communication: a working relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;39(2–3):191. doi:10.1016/S0738-3991(99)00040-3

25. Alananzeh IM, Kwok C, Ramjan L, Levesque JV, Everett B. Information needs of Arab cancer survivors and caregivers: a mixed methods study. Collegian. 2019;26(1):40–48. doi:10.1016/j.colegn.2018.03.001

26. So WW, Bei AY, Lai MT, Choi KC, Li PC. Factors in the prioritization of information needs among Hong Kong Chinese breast cancer patients. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2015;2(3):176. doi:10.4103/2347-5625.163620

27. Ankem K. Factors influencing information needs among cancer patients: a meta analysis. Libr Inf Sci Res. 2006;28(1):7–23. doi:10.1016/j.lisr.2005.11.003

28. Husson O, Mols F, van de Poll-franse LV. The relation between information provision and health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(4):761–772. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdq413

29. Uysal N, Toprak FU, Kutlutsurkan S, Erenel AS. Symptoms experienced and information needs of women receiving chemotherapy. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2018;5(2):178–183. doi:10.4103/apjon.apjon_69_17

30. Vall Casas A, Rodríguez Parada C. Concepción “Patients’ right to information: a review of the regulatory and ethical framework”. BiD. 2008;21.

31. Tigeneh W, Molla A, Abreha A, Assefa M. Pattern of cancer in tikur anbessa specialized hospital oncology center in Ethiopia from 1998 to 2010. Int J Cancer Res Mol Mech. 2015;1(1).

32. Gebremariam A, Addissie A, Worku A, Assefa M, Kantelhardt EJ, Jemal A. Perspectives of patients, family members, and health care providers on late diagnosis of breast cancer in Ethiopia: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0220769. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0220769

33. Federal Ministry of Health Ethiopia. Disease prevention and control directorate. National cancer control plan. 2016–2020. Available from: https://www.iccpportal.org/sites/default/files/plans/NCCP%20Ethiopia%20Final%20261015.pdf.

34. Aberaraw R, Boka A, Teshome R, Yeshambel A. Social networks and quality of life among female breast cancer patients at tikur anbessa specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia 2019. BMC Women’s Health. 2020;20(1):50. doi:10.1186/s12905-020-00908-8

35. Mekuria AB, Erku DA, Belachew SA. Preferred information sources and needs of cancer patients on disease symptoms and management: a cross-sectional study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1991–1997. doi:10.2147/PPA.S116463

36. Wondimagegnehu A, Abebe W, Abraha A, Teferra S. Depression and social support among breast cancer patients in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):836. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-6007-4

37. Harrison DE, Galloway S, Graydon JE, Palmer-Wickham S, Rich-van der Bij L. Information needs and preference for information of women with breast cancer over a first course of radiation therapy. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;38:217–225. doi:10.1016/S0738-3991(99)00009-9

38. Lee YM, Francis K, Walker J, Lee SM. What are the information needs of Chinese breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy? Eur J Oncol. 2004;8(3):224–233.

39. Galloway S, Graydon J, Harrison D, et al. Informational needs of women with a recent diagnosis of breast cancer: development and initial testing of a tool. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:1175–1183. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.19970251175.x

40. Namushi LB. Patricia katowa mukwato information needs of breast cancer patients at cancer diseases hospital, Lusaka, Zambia. Adv Breast Cancer Res. 2020;9:34–53. doi:10.4236/abcr.2020.92004

41. Mohamed LA, El-Sebaee HA. Comparison of informational needs among newly diagnosed breast cancer women undergoing different surgical treatment modalities. J Biol Agric Healthcare. 2013;3(13):73–84.

42. Sayed SS, Abo Zead SE, Ali GA. Informational needs among women with newly diagnosed breast cancer: suggested nursing guidelines. Assiut Sci Nurs J. 2017;5(12):117–125.

43. Yi M, Cho J, Noh DY, Song MR, Lee JL, Juon HS. Informational needs of Korean women with breast cancer: cross-cultural adaptation of the toronto informational needs questionnaire of breast cancer. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2007;1(3):176–186. doi:10.1016/S1976-1317(08)60020-1

44. Hazel RM, Templton VEC. Adaptation of an instrument to measure the informational needs of men with prostate cancer. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35(3):357–364. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01883.x

45. Tsaras K, Papathanasiou IV, Mitsi D, et al. Assessment of depression and anxiety in breast cancer patients: prevalence and associated factors. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19(6):1661–1669.

46. Al-Azri M, Al-Awisi H, Al-Rasbi S, et al. Psychosocial impact of breast cancer diagnosis among omani women. Oman Med J. 2014;29(6):437–444. doi:10.5001/omj.2014.115

47. Seah DS, Lin NU, Curley C, Weiner EP, Partridge AH. Informational needs and the quality of life of patients in their first year after metastatic breast cancer diagnosis. J Community Support Oncol. 2014;12(10):347–354. doi:10.12788/jcso.0077

48. Kraemer LM, Stanton AL, Meyerowitz BE, Rowland JH, Ganz PA. A longitudinal examination of couples’ coping strategies as predictors of adjustment to breast cancer. J Fam Psychol. 2011;25(6):963–972.

49. Lashbrook MP, Valery PC, Knott V, Kirshbaum MN, Bernardes CM. Coping strategies used by breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors: a literature review. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41(5):E23–E39. doi:10.1097/NCC.0000000000000528

50. Leydon GM, Boulton M, Moynihan C, et al. Cancer patients’ information needs and information seeking behaviour: in depth interview study. BMJ. 2000;320(7239):909–913. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7239.909

51. Kershaw T, Northouse L, Kritpracha C, Schafenacker A, Mood D. Coping strategies and quality of life in women with advanced breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psychol Health. 2007;19(2):139–155. doi:10.1080/08870440310001652687

52. Birhan Legese AAea, 2017. Available at information needs of breast cancer patients attending care at tikur anbessa specialized hospital, Addis Ababa Ethiopia. 2017.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.