Back to Journals » Psychology Research and Behavior Management » Volume 15

Individual Job Crafting and Supervisory Support: An Examination of Supervisor Attribution and Crafter Credibility

Authors Ji S

Received 28 April 2022

Accepted for publication 16 July 2022

Published 26 July 2022 Volume 2022:15 Pages 1853—1869

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S372639

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Igor Elman

Shunhong Ji

College of Business, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China

Correspondence: Shunhong Ji, College of Business, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, Shanghai, People’s Republic of China, Tel +86 156 0516 7360, Email [email protected]

Purpose: Drawing upon attribution theory, this study investigates the mediating role of supervisor-attributed motives in the relationship between employees’ job crafting and supervisory support, as well as the moderating effect of crafter credibility on leaders’ attributional process, which in turn determines leaders’ willingness to support.

Methods: A total of 264 employees and 61 supervising managers participated in the two-wave dyadic survey. To test our hypotheses, we performed the hierarchical regression and conducted bootstrapping analyses using Hayes PROCESS Model.

Results: Findings indicated that approach (avoidance) job crafting has a positive (negative) indirect relationship with supervisory via the supervisor’s prosocial motives (egoistic intentions) attribution. In addition, the crafter credibility strengthens (weakens) leaders’ positive (negative) attribution and support for approach (avoidance) job crafting, revealing a significant moderated mediation.

Conclusion: In summary, the present research advances our understanding of the social consequences of individual job crafting and explains the potential risks and rewards of individual job crafting by identifying supervisors’ differential attributions for this working behavior. In addition, it enhances the knowledge of the contingency of managers’ responses to employees’ job crafting by examining the moderating role of crafter credibility.

Keywords: approach job crafting, avoidance job crafting, prosocial motives attribution, egoistic intentions attribution, crafter credibility, supervisory support

Introduction

Job crafting, which refers to individuals’ actively shaping, molding, and changing their jobs and work,52,63 is increasingly key for organizations to survive dynamic environments and achieve sustainable development.44 Research on job crafting has shown positive effects of employees’ job crafting on person-job fit,54 individual attitudes and well-being,51,65 and adaptability.32 Despite these benefits, recent research has argued that job crafting, as an individualized and bottom-up job re-design, elicits different reactions and responses from managers owing to the status quo being challenged and the environment being changed.56 For instance, studies have suggested that supervisors do not always appreciate employees’ job crafting, and even have negative reactions to such self-initiatives if the activity is perceived as an image risk.34,50 Therefore, leaders’ response essentially depends on how they interpret the motivation for employees’ job crafting.

Research on how leaders perceive and attribute employees’ job crafting has become an important subject because leaders’ attributions directly influence their willingness to support, and, ultimately, determine whether the employee can undertake successful job crafting and achieve the expected goals.61 First and foremost, in an organization, monitoring and evaluating subordinates’ working behavior are part of managers’ responsibility. When individuals initiate changes to existing task procedures and work norms, it is essential for leaders to assess and decide whether to accept these job changes and adjustments.20 In addition, as stakeholders in the social context of employees’ job crafting, leaders not only master the resources (eg, information resources) that employees need to redesign their job,60 but also associate with other subjects, such as colleagues involved in employees’ job crafting and cross-departmental collaboration networks.59 Therefore, leaders’ attributions and support for employees’ job crafting play a vital role in the process. Exploring this topic can not only help better understand the outcomes of employees’ job crafting, but also enhance knowledge about the mechanism of others’ reactions to individual job-crafting behaviors in social contexts.

Unfortunately, research concerning how supervisors attribute employees’ job crafting is conspicuously absent from the literature. Previous studies have investigated managerial perceptions of the benefits and risks of employees’ job crafting through theoretical analysis or qualitative interviews.34,50 However, these studies did not conduct empirical investigations to examine the underlying reasons and mechanisms. To a large extent, this omission may be due to two issues: first, a lack of in-depth analysis of the concept of job crafting. According to the framework developed by Zhang and Parker, individual job crafting presents different behavioral orientations, including approach and avoidance job crafting.65 Approach job crafting and avoidance job crafting are conceptually distinct and, hence, will lead to leaders making differential attributions. To be specific, approach job crafting is proactive crafting behavior—effortful and directed toward improvement-based goals.8 Individuals create opportunities beneficial to the task and job by seeking challenges and resources, such as actively learning new skills to solve problems at work.33 Accordingly, approach job crafting may promote managers’ prosocial motivation attribution. Meanwhile, avoidance job crafting, defined as a prevention-oriented self-initiative, will result in managers’ egoistic intentions attribution. Because these crafting activities usually serve the purposes of evading, reducing, or eliminating part of one’s work,11 such as reducing hindering and social demands, supervisors are more likely to interpret this behavior as serving individuals’ own interest. An existing study has revealed supervisors’ responses to avoidance job crafting and proposed that approach job crafting would moderate the process. To extend the current research, we distinguish the differential effects of approach and avoidance job crafting on leaders’ response and explain the mechanism from the behavioral attribution view, which is more in line with the social context of job crafting.

In addition, attribution theory22 holds that the observer’s attribution will not only depend on what actors do but also on who they are.28 Current research has focused predominantly on the impact of job crafting behaviors: far too little attention has been paid to investigating the influence of the source factor, ie, job crafters. Moreover, extant studies examining the boundary conditions of others’ reactions to individual job crafting are centered on contextual factors, such as task context (eg, job autonomy and ambiguity) and social context (eg, interdependence and social support),13 ignoring the role of job crafter in the process. As one of the most prominent source variables, crafter credibility describes the trustworthiness and expertise of the employee who engages in job crafting,5,65 and has been demonstrated to positively influence the manager’s perception and evaluation of individuals’ proactive working behavior.62 Consequently, we propose that the beneficial effect of approach job crafting is more pronounced for employees with high credibility than for those who are less credible. At the same time, crafter credibility may also buffer the negative effect of avoidance job crafting.

In the present research, building upon the attribution perspective,22 we build an integrative model to examine the mechanism underpinning supervisory support toward employees’ job crafting. We explain managers’ differential attributions for approach and avoidance job crafting, and clarify how such attributions will influence subsequent supervisory support. Further, to illuminate the role of job crafter’s characteristics in the judgment process, we explore the moderating effect of crafter credibility on supervisor-attributed motives for employees’ job crafting.

In summary, our research makes several contributions to the job crafting literature. To start with, shifting to the manager’s perspective, we advance our understanding of the social consequences of individual job crafting.56 Drawing on attribution theory, we offer a comprehensive view of supervisors’ reactions to employees’ job crafting. Second, by identifying supervisors’ differential attributions to approach and avoidance job crafting, we explain the mechanism of supervisors’ responses13 and describe the potential risks and rewards of individual job crafting in the social context. In addition, we enhance the knowledge of the contingency of managers’ responses to employees’ job crafting by revealing the moderating effect of crafter credibility. By doing so, we address the knowledge gap arising from that “while job-crafting outcomes and antecedents have often been studied, the studied mechanisms and boundary conditions are rather limited.”56 Finally, from a practical view, our work also offers insights for employees to engage in job crafting in an effective way,42 and provides implications for managers to find better ways to improve employees’ job crafting at work.

Theory Development and Hypotheses

Supervisor’s Perception of Individual Job Crafting

We direct our theoretical and empirical attention to the supervisor’s perspective because managers play a critical role in individual job crafting. They not only take the responsibility to monitor and evaluate employees’ proactive job redesign and adjustments at work, but can also influence the social context related to individual job crafting. Therefore, supervisors can be a bottleneck in employees’ pursuit of the goals of job crafting. If the manager fails to appreciate and support such activity, they will discourage employees from engaging in it. Because job crafting involves changing the existing work rules and challenging the current norms,65 it may be particularly susceptible to such cues from leaders given that it entails potential threats and risks.34,55

In line with attribution theory, when the actor’s behavior deviates from accepted norms and expectations, observers are inclined to offer explanations for these inconsistencies and deviations.22 Hence, when employees proactively make changes to certain aspects of their work via job crafting, supervisors will seek to generate attributions to explain the deviations that come with this behavior, namely prosocial motives or egoistic intentions.49 Taking different orientations of approach and avoidance job crafting into account,14 managers will create distinct perceptions and explanations of the actor’s behavior, thereby generating different attributions.

Prosocial Motives Attribution for Approach Job Crafting

Approach job crafting, defined as crafting activities in which individuals increase resources and challenge job demands to solve problems and achieve improvement-based goals,8 has been shown to be associated with positive individual and organizational outcomes. Using meta-analysis, scholars have found that approach job crafting significantly promoted employees’ learning and competence,65 work engagement,33 and job satisfaction.51 In addition, research has indicated its benefits to other coworkers. More specifically, using the diary study,43 Peeters et al revealed the direct crossover of approach job crafting from the focal employee to coworker. Bakker et al4 found a reciprocal relationship between dyad members’ (the actor and the coworker) approach job crafting. In the modeling process, the actor’s approach job crafting was positively associated with the coworker’s work engagement. Finally, employees’ approach job crafting has also been found to benefit organizations by enhancing individual organizational commitment51 and reducing turnover intention.51 Likewise, it is positively related to higher levels of task and contextual performance.

Considering these abovementioned positive impacts, supervisors are more likely to believe that the employee’s behavior is driven by concern for others and the organization19 and attribute strong prosocial motives to individual approach job crafting. As such, we expect:

Hypothesis 1: An employee’s approach job crafting is positively related to the supervisor’s prosocial motives attribution.

Research has suggested that supervisor-attributed motives for the employee’s behavior will influence the supervisor’s reactions to these employees.22 Specifically, the supervisor’s attribution of prosocial motives is positively related to their willingness to support.58 Based on the positive relationship between individual approach job crafting and prosocial motives attribution discussed above, we propose that the employee’s approach job crafting may have a positive effect on supervisory support via prosocial motives attribution. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2: An employee’s approach job crafting has a positive indirect relationship with supervisory support through the supervisor’s prosocial motives attribution.

Egoistic Intentions Attribution for Avoidance Job Crafting

Because of reducing hindering and social demands and systematic forms of work withdrawal,39,52 individual avoidance job crafting has been demonstrated to be negatively related to opportunities for growth and development65 and work engagement.51 Furthermore, this prevention-oriented crafting behavior may lead to detrimental effects on colleagues and the organization. For instance, evidence has shown that employees’ avoidance job crafting will lead to lower coworker work engagement4 and higher levels of workload and conflict.53 Additionally, due to reductions in the task and social boundaries at work, research has indicated employees’ avoidance job crafting is positively associated with turnover intentions51 and negatively associated with job performance.33

According to accepted workplace norms, employees are expected to engage in positive behaviors and contribute to the team.24 Observers will make negative attributions for behaviors that violate these norms. Thus, individual avoidance job crafting is especially likely to be regarded as serving the employee’s interests instead of the desire to benefit other people or the organization. Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 3: An employee’s avoidance job crafting is positively related to the supervisor’s egoistic intentions attribution.

Learning from the attributional processes of leaders in leader-member interactions,22 managers’ egoistic intentions attribution for subordinates’ behavior is negatively related to supervisory support.58 Because the employee’s avoidance job crafting positively relates to supervisor-attributed egoistic intentions, this attribution will, in turn, result in lower leaders’ support for the employee. Hence, we argue that egoistic intentions attribution mediates the indirect effect of avoidance job crafting on supervisory support. Altogether, we propose:

Hypothesis 4: An employee’s avoidance job crafting has a negative indirect relationship with supervisory support through the supervisor’s egoistic intentions attribution.

The Moderating Effect of Crafter Credibility

Attribution theory further suggests that observers are more likely to consider multiple available cues (eg, the actor’s characteristics) in order to understand the cause of the event.28 Under this circumstance, supervisors’ attribution for employees’ job crafting will be affected by their perception of the job crafter.55 Credibility, one central dimension of individual characteristics, signals others’ perception of the legitimacy and trustworthiness of the employee’s working behavior.46 Because credibility is more in line with the social norms and supervisor’s expectations of subordinates, for example, strong expertise and high benevolence,5 it has been shown to be positively related to leaders’ perceived prosocial motives29 and more favorable evaluation of the employee.62 Based on this, we suggest that credibility will influence supervisors’ attribution for the employee’s job crafting, as well as subsequent supervisory support.

Specifically, crafter credibility strengthens the positive effect of individual approach job crafting on prosocial motives attribution. In essence, as available cues in forming judgment, crafter credibility explains the job crafter’s positive characteristics, aligning with the positive impact of approach job crafting. Drawing upon attribution theory,28 these two consistent sources of information augment each other in determining attributors’ explanations for actors’ intentions behind a behavior. Accordingly, approach job crafting from employees with high credibility will be attributed to higher prosocial motives. In contrast, crafter credibility will reduce leaders’ negative motivation attributed to individual avoidance job crafting. In the attribution process, positive cues inferred from crafter credibility are inconsistent with the potential negative impacts of avoidance job crafting. As a result, it is difficult for managers to create a coherent story of the reason for the employee’s avoidance job crafting. In this context, managers are likely to discount the inconsistent cues and minimize their egoistic intentions attribution for employees’ negative behaviors, given that crafter credibility is a more stable characteristic.25,28 Thus, supervisors will attribute lower egoistic intentions to individual avoidance job crafting when the job crafter has high credibility.

This interactive effect may have a profound impact on managers’ attribution for employees’ job crafting and results in different perceptions, thus influencing supervisory support. Therefore, we also suggest that the indirect effect of the employee’s job crafting on supervisory support via leaders’ distinct attributions is moderated by crafter credibility. Taking together, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 5: The crafter’s credibility strengthens (a) the positive relationship between approach job crafting and prosocial motives attribution, and (b) the positive indirect effect of approach job crafting on supervisory support via prosocial motives attribution. Hypothesis 6: The crafter’s credibility weakens (a) the positive relationship between avoidance job crafting and egoistic intentions attribution, and (b) the negative indirect effect of avoidance job crafting on supervisory support via egoistic intentions attribution.

Based on the hypotheses discussed above, we present our proposed research model in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1 The conceptual model of this study. |

Methods

Sample and Procedures

The survey was conducted at a large insurance company in eastern China. An insurance company is an ideal sample for our study because employees’ proactive behaviors and work redesign are expected in the insurance profession.38 Further, frequent communication and regular meetings within the sales team also ensure that supervisors are able to accurately observe and evaluate employees’ different job crafting behaviors. A randomized cluster sampling was used to select respondents from branches of the company at different sites. The inclusion criteria for participants included: first, respondents should be working in the company as a regular staff; second, clear dyadic relationships (ie, supervisors and subordinates) should exist; and third, respondents should have no cognitive impairment and be able to understand the questions in the survey. Thus, participants were employees and their supervising managers from different insurance sales teams. Their main job responsibility was to sell personal insurance plans and provide customers with insurance services. With the help of the Human Resources Department, we invited employees and their supervisors to participate in the online survey. We first briefed them on the purpose and procedures of our survey and then informed them of voluntary participation and ensured confidentiality. On average, the supervisor’s span of control was 4.61 people, ranging from three to six.

Our survey was conducted in two waves separated by approximately four weeks. At Time 1, we invited 323 employees to report their approach and avoidance job crafting behaviors at the workplace. We received 295 completed questionnaires (response rate = 91.33%). Then, we asked 70 supervisors of these 295 employee respondents to assess the subordinate’s credibility and past performance and rate their leader-member exchange (LMX) with the subordinate. We collected 264 matched questionnaires from 61 supervisors (response rate = 87.14%). At Time 2, we asked those 61 supervisors to report their perceived prosocial motives and egoistic intentions regarding employees’ job crafting as well as their willingness to support. All of these 61 supervisors responded to the questionnaires (response rate = 100%). Thus, the final sample consisted of 264 employees and 61 supervisors. Table 1 presents the demographics of the participants. For the employee sample, 51.52% were female and 60.61% were above 30 years of age. On average, 60.23% had been working in their current job for more than 3 years and 87.88% held a bachelor’s degree or above. Among the supervising managers, 47.54% were female and 80.33% were above 30 years old. Regarding work tenure and education level, 54.10% had been in work for more than five years and 91.80% held a bachelor’s degree or above.

|

Table 1 Demographic Data of Participants |

Measures

All survey materials in this study were presented in Chinese, consistent with the translation and back-translation procedures proposed by Brislin.7 All responses were made on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Approach Job Crafting

Employees were asked to report their approach job crafting by using a fifteen-item subscale of the job crafting scale developed by Tims et al.52 These items depict behaviors associated with increasing structural and social job resources and challenging job demands. A sample item is “I regularly take on extra tasks even though I do not receive extra salary for them”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.96.

Avoidance Job Crafting

We measured the employee’s avoidance job crafting with a six-item subscale of the job crafting scale developed by Tims et al.52 An example item is “I try to ensure that my work is emotionally less intense”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95.

Prosocial Motives Attribution

Following Grant’s research,19 supervisors were asked to report their attributed prosocial motives for the employee’s behavior with a four-item measure. An example item is “This employee wants to help others through his/her job crafting”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.87.

Egoistic Intentions Attribution

To measure supervisor-attributed egoistic intentions of the employee’s job crafting, we used a four-item scale from Urbach, Fay, and Lauche.59 A sample item is “This employee’s job crafting safeguards his/her own interests”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92.

Crafter Credibility

Supervisors assessed the crafter credibility using Ohanian’s five-item measure.40 An example item is “The employee is an expert in what he does”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92.

Supervisory Support

We rated the supervisor’s support for the job crafter using a 9-item scale from Greenhaus, Parasuraman, and Wormley.23 A sample item is “I will give the employee helpful feedback about his/her performance”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.94.

Control Variables

To offer a rigorous examination of our model, we controlled for several factors influencing supervisors’ evaluation of their subordinates’ job crafting. First, drawing on the research from Green et al,21 the employees’ demographic characteristics and background factors could influence leaders’ perceptions and evaluations of their working behaviors. Thus, we controlled for the impact of demographic variables (ie, gender, age, tenure, and education) in this study.57 Then, previous research has suggested that the LMX between the employee and the leader may affect managers’ responses to subordinates’ proactive behaviors at work and subsequent evaluation of the employee.27 Therefore, we controlled for supervisors’ LMX with the job crafter using Graen and Uhl-Bien’s seven-item scale.18 A sample item is “I would be personally inclined to use my power to help the employee solve problems in work”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.94. In addition, with the dyadic supervisor-employee study, Fong and her partners pointed out that employees’ past performance may influence supervisors’ responses to employees’ job crafting.16 Consequently, we also controlled for employees’ past performance by using a three-item scale from MacKenzie, Podsakoff, and Fetter.35 A sample item is “This employee is outstanding at his/her work”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

Common Method Bias Test

Although we employed a two-wave multi-source research design to minimize the influence of common method variance, the data at Time 2, including the moderator, mediators, and dependent variable, were all filled in by the supervisors themselves. Thus, it is essential to examine the possible methodological bias. Based on the Harman’s single-factor test,45 we found that the maximum factor loading of the unrotated common factors accounted for 31.42% of the variance, which did not exceed the 40% criterion and indicated no significant common method bias in our study.

Validity and Reliability

Prior to testing the hypotheses, we used Mplus 8.0 to conduct a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) to examine the convergent and discriminant validity of our measures.2 As shown in Table 2, the results indicated that the six-factor model fit the data better than any of the alternative models (χ2/df = 2.25, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.06, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.89). Then, following the recommendations of the research, we assessed the convergent validity by testing composite reliability (CR) and the average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct.17 According to the results in Table 3, all items’ standardized factor loadings were greater than 0.70, and the CR value of each variable was higher than 0.8. In addition, the AVE values for each construct exceeded the threshold value (0.50), suggesting good convergent validity of all variables in the study.

|

Table 2 Model Fit Results for Confirmatory Factor Analyses |

|

Table 3 Factor Loading and Convergent Validity |

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics and correlations for the study variables. As shown in Table 4, approach job crafting was positively associated with supervisor’s prosocial motives attribution (r = 0.50, p < 0.01) and supervisory support (r = 0.39, p < 0.01). Additionally, avoidance job crafting was positively related to supervisor’s egoistic intentions attribution (r = 0.53, p < 0.01) but negatively related to supervisory support (r = –0.37, p < 0.01). Furthermore, supervisor’s prosocial motives attribution was significantly and positively related to supervisory support (r = 0.63, p < 0.01), while egoistic intentions attribution was negatively related to supervisory support (r = −0.42, p < 0.01). Next, we conducted hierarchical multiple regressions to examine the direct effects proposed in Hypothesis 1 and 3. Moreover, we utilized Hayes’s PROCESS macro to test the indirect effects (Hypothesis 2 and 4) and moderating and conditional effects (Hypothesis 5 and 6), respectively.

|

Table 4 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Variables |

Hypothesis Testing

Tests of Direct Effects

Using SPSS 23.0, we performed hierarchical multiple regressions to examine the impact of employees’ job crafting on supervisor-attributed motives. Results in Table 5 showed that approach job crafting positively related to the supervisor’s prosocial motives attribution (b = 0.54, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 1. In addition, the hierarchical regression result indicated a significant positive association between avoidance job crafting and egoistic intentions attribution (b = 0.50, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 3.

|

Table 5 Results of the Hierarchical Regressions |

Tests of Indirect Effects

The PROCESS macro, based on bootstrapping analyses, can effectively test multiple mediation effects, moderation effects, moderated mediation effects, and mediated moderation effects. In addition, it can examine mediation and moderation models with control variables.26 Thus, we utilized PROCESS macro to test the indirect effects as well as the moderating and conditional effects in our study.

On the basis of Hayes’s PROCESS macro (Model 4),26 we examined the mediation effect and found a significant indirect effect of approach job crafting on supervisory support via prosocial motives attribution (b = 0.28, 95% CI = [0.20, 0.37]). Meanwhile, the direct effect of approach job crafting on supervisory support was not significant (b = 0.10, 95% CI = [–0.01, 0.22]), which is consistent with the hierarchical regression result in Table 5 (M5). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported and the indirect effect was a full mediation. Similarly, avoidance job crafting has a negative indirect association with supervisory support through the supervisor’s egoistic intentions attribution (b = –0.11, 95% CI = [–0.16, –0.06]). Moreover, consistent with the result in Table 5 (M10), the direct effect of avoidance job crafting on supervisory support was also significant (b = –0.14, 95% CI = [–0.24, –0.05]). Thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported and the indirect effect was a partial mediation.

Tests of Moderating and Conditional Effects

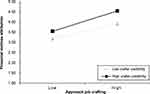

To investigate the moderating role of crafter credibility on supervisors’ attribution and support, we grand-mean centered all independent variables.1 Results of moderating effect analysis based on PROCESS macro (Model 1) showed that crafter credibility significantly moderated the relationship between approach job crafting and prosocial motives attribution (b = 0.14, p < 0.01). A graph illustrating this interaction is shown in Figure 2. Then, the simple slope tests revealed that the effect of approach job crafting on prosocial motives attribution was significant and positive at high levels of crafter credibility (+1 SD) (b = 0.50, p < 0.01) but significantly weaker at low levels of crafter credibility (–1 SD) (b = 0.23, p < 0.01). Furthermore, using PROCESS macro (Model 7), we analyzed the conditional effect and found that crafter credibility significantly moderated the indirect effect of approach job crafting on supervisory support via prosocial motives attribution (Index = 0.07, 95% CI = [0.04, 0.10]). Table 6 showed that there were significant differences in mediating effects at different levels of crafter credibility. Therefore, Hypothesis 5 was supported. With the same method, we confirmed the moderating effect of crafter credibility on the association between avoidance job crafting and egoistic intentions attribution (b = –0.13, p < 0.01). As presented in Figure 3, a test of simple slopes suggested that the relationship between avoidance job crafting and egoistic intentions attribution was significant and positive at low levels of crafter credibility (–1 SD) (b = 0.30, p < 0.01), but not significant at high levels of crafter credibility (+1 SD) (b = 0.05, p > 0.05). Moreover, results of conditional effect analysis indicated that crafter credibility significantly moderated the indirect effect of avoidance job crafting on supervisory support via egoistic intentions attribution (Index = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.04]). Each mediation at different levels of crafter credibility is displayed in Table 6. Thus, Hypothesis 6 was supported.

|

Table 6 Results of the Conditional Effect |

|

Figure 2 Moderating effect of crafter credibility on the relationship between approach job crafting and prosocial motives attribution. |

|

Figure 3 Moderating effect of crafter credibility on the relationship between avoidance job crafting and egoistic intentions attribution. |

Supplemental Analysis

To check the robustness of our findings, we further conducted the data analysis on the latent level and comprehensively tested the hypothesized model using the SEM in Mplus 8.0. Results supported all hypotheses in the study and showed no significant difference under different methods.

Discussion

Prior studies have noted that supervisors may have different responses to employees’ job crafting behaviors.34,50 Despite the important role of leaders in evaluating and supporting job crafting,55 there remains a paucity of evidence on the mechanism and boundary condition of managerial reactions, especially on how managers interpret the motivation for employee’s job crafting. This study extends the literature by investigating how supervisors make attributions for different job crafting behaviors. Further, we examined the moderating effect of crafter credibility, a vital source factor, on leaders’ attributional process.

To answer the research question, we built on attribution theory to propose that supervisors would generate distinct attributions to approach and avoidance job crafting, which are in turn related to supervisory support. Besides, we explored the boundary condition of leaders’ attribution and demonstrated how crafter credibility affected each pathway. In summary, the empirical results supported our hypotheses. We found that leaders attributed prosocial motives to approach job crafting and offer higher level of support. Moreover, prosocial motives attribution fully mediated the effect of approach job crafting on supervisory support, which further revealed the dominant pathway of prosocial motives attribution. It suggested that managers supported employees’ approach job crafting primarily because they regarded employees’ seeking job challenges and resources as serving the interests of the organization, while avoidance job crafting lead to supervisors’ egoistic intentions attribution and lower level of support. More importantly, the partial mediation effect indicated other potential mediating mechanisms explaining supervisory support for employees’ avoidance job crafting, in addition to the attributional pathway (ie, egoistic intentions attribution) in this study: for instance, leaders perceived destructiveness of avoidance job crafting or leaders’ negative emotion caused by this avoidance-oriented crafting behavior.10,16

In addition, beyond examining the influence of job crafting content highlighted in previous literature, we also found significant moderating effect of crafter credibility on leaders’ attribution. Results showed that crafter credibility strengthened the positive relationship between approach job crafting and prosocial motives attribution but weakened the positive relationship between avoidance job crafting and egoistic intentions attribution. We also found that crafter credibility significantly influenced the indirect effects. The positive indirect effect of approach job crafting on supervisory support via prosocial motives attribution was strengthened when the employee had high crafter credibility. Furthermore, the negative indirect effect of avoidance job crafting on supervisory support via egoistic intentions attribution was weakened when the employee had high crafter credibility. These results suggest that crafter credibility, as a positive source factor, could enhance the benefits of approach job crafting and reduce the burdens of avoidance job crafting in the attributional process. The findings provide new insights into the literature by uncovering the impact of job crafter’s characteristics on managerial reactions to job crafting behaviors. We discuss the theoretical contributions and practical implications below.

Theoretical Contributions

The primary contribution of this paper is to investigate the consequences of individual job crafting from the manager’s perspective, which can extend the current theoretical framework of job crafting in the social context.55 Compared with the individual-level and team-level outcomes of job crafting, how leaders respond to individual job crafting has received scant attention in the literature. Considering the changes and impacts employees’ job crafting brings to the organization,56 we examine the relationship between employees’ job crafting and supervisory support. Our research will further develop this literature by encouraging more future work to explore the impacts of job crafting from the view of other stakeholders.

Second, our research contributes to a more thorough understanding of why managers support or reject employees’ job crafting. Drawing on the attribution theory, we clarify that approach and avoidance job crafting lead to distinct supervisor-attributed motives, thereby influencing supervisors’ willingness to support. While prior research differentiates the outcomes of approach and avoidance job crafting,65 we further empirically explain different outcomes resulting from observers’ distinct perceptions of these two crafting behaviors. Based on the attributional process, our findings advance more reflections on others’ reactions to job crafting and more nuanced distinctions between different forms of individual job crafting. For instance, the difference in the mediating effects suggested that it is essential to conduct more studies to investigate the mechanisms underlying leaders’ response to avoidance job crafting. Compared with the full mediation effect of prosocial motives attribution on the relationship between approach job crafting and supervisory support, the partial mediation effect indicated that avoidance job crafting will influence supervisory support via other potential pathways. In general, the mechanisms explaining avoidance job crafting are more differentiated and complex than those clarifying approach job crafting. Additionally, avoidance job crafting may have positive effects on work-home enrichment and work engagement.48 In current research, a concrete theoretical framework to help us draw precise conclusions is lacking. Therefore, our findings will encourage more in-depth exploration of mediating mechanisms and advance the understanding of the concept and types of job crafting.

Third, the present research can also contribute to the development of the work goal literature, especially the investigation of work avoidance goals. Given the similarities between avoidance job crafting and work avoidance goals,15 the theoretical perspective of our study can be applied to examine work avoidance goals. Specifically, the current work avoidance goal literature focuses on distinguishing between the concepts of achievement goals and work avoidance goals, including structure, antecedents, and outcomes.30 However, most of these studies analyze the differences between concepts from the perspective of the actors themselves, ignoring the role of other stakeholders. Furthermore, learning from the mediating mechanisms and boundary conditions in our study, we propose to explore the mechanisms of the work avoidance goal’s outcomes and what factors influence this process, which will not only offer a comprehensive picture of work avoidance goal’s nomological network, but also help us to gain a clearer distinction between work avoidance goal and achievement goals.

Finally, we offer novel insights into the current literature by discussing the conditions under which individuals engaging in job crafting are more likely to obtain the supervisor’s support. Our findings indicate that crafter credibility could help the job crafter to enhance the positive impacts of approach job crafting and buffer the negative influences of avoidance job crafting, thus improving the supervisor’s support. On one hand, the moderating effect in this study will be beneficial to explaining the inconsistent conclusions in prior studies. For example, crafter credibility may illustrate why individual approach job crafting sometimes fails to bring expected supervisory support and positive evaluation. On the other hand, by integrating the crafter credibility into the attributional process, we extend our knowledge about leaders’ assessment of employees’ job crafting and encourage more research to study the boundary condition of individual job crafting’s consequences. More importantly, beyond the social context and job characteristics factors analyzed as moderators in the literature, we enrich the theoretical framework of job crafting by demonstrating the role of job crafter’s characteristics, which yield an effective combination of job crafters and evaluators.65

Practical Implications

Our findings have principal implications for both managers and employees. First, from the perspective of the leader, the results imply that it is important for them to monitor employees’ job crafting at the workplace. Owing to different orientations of job crafting, leaders ought to enhance the positive effects of approach job crafting and mitigate the potential negative impacts of avoidance job crafting.16 To achieve this goal, it is vital to identify the focus of evaluating employees’ work-redesign behaviors in the human resource management practices, for example, updating the performance evaluation criteria based on the organizational strategy.41,65 The practice will not only help leaders to better understand the emphasis of managing subordinates’ proactivity, but also enable them to actively guide employees to enhance their approach job crafting and reduce avoidance job crafting. Ultimately, it will promote the development of the organization. In addition to performance appraisal, another effective intervention is training. On the one hand, it’s beneficial for supervisors to promote their interactions with subordinates through the training. Consequently, leaders are more likely to know employees’ crafting behaviors and evaluate whether these job crafting activities are useful or harmful for others and the organization.47 On the other hand, with the help of the training, leaders can develop employees’ awareness of their different job crafting activities’ influences. In this way, it contributes to a positive job crafting climate.

For employees, our research provides insights into engaging in job crafting activities in an effective way. Managers’ perceptions and attributions not only depend on what employees do but also on who they are. Therefore, employees should first take into account the content of job crafting and endeavor to seek a balance between individual needs and organizational developments. For example, they can engage in regular conversations with managers (eg, formal and informal communications) in order to align their job crafting better with the organization’s goals.9 More importantly, the results suggest that high crafter credibility can strengthen managers’ positive perceptions of approach job crafting and weaken the negative perceptions of avoidance job crafting. Therefore, job crafters should pay more attention to improving their credibility. For instance, they can participate in learnings and training (eg, on-the-job training or employee development plan) to enhance expertise and enrich job crafting experiences to gain more trustworthiness.40 Based on these efforts, job crafters can earn managers’ positive evaluation and support, thereby facilitating successful job crafting.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The present research is subject to several limitations that suggest directions for future work. First, the present study focused on analyzing cognitive pathways and did not check other alternative mechanisms, which researchers can examine in the future. Specifically, research on leaders’ responses points out several mediation mechanisms, such as cognitive, affective, and behavioral mechanisms. Mayer et al37 illustrated the cognitive and affective mechanisms underpinning leaders’ assessments of employees’ proactive behaviors. Xu et al64 emphasized the important role of managers’ emotional state in evaluating employees’ speaking up. Thus, based on different mechanisms, there is abundant room for further progress in explaining leaders’ responses to employees’ job crafting.

Another limitation is that we did not test the influence of the interaction between approach and avoidance job crafting on our results. Previous research suggests that the detrimental impact of avoidance job crafting decreases when job crafters combine it with approach job crafting.36 Further, employees would normally engage in both approach and avoidance job crafting in their work. Although it is not the focus of our research to examine job crafting profiles, it would be interesting to examine this issue in greater depth, which can offer a valuable extension of the concept of job crafting.

Third, going beyond the actor’s behavior and characteristics, future work is required to examine other potential moderators. Building on attribution theory, the observer’s characteristics and contextual factors can also influence the attributional process. For example, the leader’s openness12 and sense of power58 have been demonstrated significantly affect managers’ judgment of subordinates’ proactivity. In addition, prior studies have indicated that the power distance climate in the organization31 can influence others’ perceptions of employees’ self-initiative. Therefore, in future investigations, we encourage scholars to examine additional moderators to depict a full picture of this attributional process.

Fourth, given the changes and dynamics of supervisor-subordinate interaction and employees’ job crafting,3 we encourage future research to contribute to this literature by investigating the evolution of leaders’ attributional process. Beyond the longitudinal research design in our study, more rigorous studies, like multi-wave research with multi-source data, are needed to explain the causal effect. For instance, we suggest that scholars can benefit from utilizing the experience sampling method6 to examine the reciprocal relationships between job crafting and supervisory support and clarify the incremental impact of specific job crafting behavior on leaders’ attribution.

Lastly, our theoretical model could be further enriched by conducting studies across a broader range of industries and geographic areas. Although we test our model with a two-wave multi-source study in a large insurance company, the survey data from a single type of company in eastern China may limit the generalizability of our findings. For instance, our findings may differ in other industries with different demands for employees’ job crafting, or national culture may influence leaders’ attribution for employees’ job crafting. To extend the generalizability of this work, we encourage researchers to test our model with samples from a wider range of industries and regions.

Conclusion

The present research extends the job crafting literature by examining the consequences of individual job crafting behaviors from the leader’s perspective. Additionally, it has significant implications for the development of research themes related to individual working behaviors. As a chief gatekeeper, managers may offer differential responses to individual job crafting. They are more likely to attribute prosocial motives to approach job crafting and egoistic intentions to avoidance job crafting, which will influence subsequent supervisory support. We also advance the existing theoretical framework by revealing the role of the job crafter in the pathway of supervisors’ attribution for specific job crafting. We found that crafter credibility could strengthen the positive relationship between approach job crafting and prosocial motives attribution but weaken the positive relationship between avoidance job crafting and egoistic intentions attribution, thereby prompting supervisory support. We encourage future research to explore the outcomes of different job crafting behaviors in the social context and the mediating mechanisms and boundary conditions of leaders’ reactions.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the author.

Ethical Statement

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Shanghai University of Finance and Economics and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Before the survey started, we introduced the purpose of our survey to all participants and informed them of voluntary participation and ensured confidentiality, which is used only for this research. After obtaining the participant’s consent, we then began the investigation and distributed the questionnaire to them.

Funding

The research underpinning this paper has received funding from Shanghai University of Finance and Economics (Grant/Award Numbers: CXJJ-2021-396).

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991.

2. Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull. 1988;103(3):411–423. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

3. Bakker AB, Oerlemans WGM. Daily job crafting and momentary work engagement: a self-determination and self-regulation perspective. J Vocat Behav. 2019;112:417–430. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2018.12.005

4. Bakker AB, Rodríguez-Muñoz A, Sanz Vergel AI. Modelling job crafting behaviors: implications for work engagement. Hum Relat. 2016;69(1):169–189. doi:10.1177/0018726715581690

5. Beatty MJ, Kruger MW. The effects of heckling on speaker credibility and attitude change. Commun Q. 2009;26(2):46–50. doi:10.1080/01463377809369293

6. Bolger N, Laurenceau JP. Intensive Longitudinal Methods: An Introduction to Diary and Experience Sampling Research. New York: Guilford Press; 2013.

7. Brislin RW. The wording and translation of research instruments. In: Lonner WJ, Berry JW, editors. Field Methods in Cross-Cultural Research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1986:137–164.

8. Bruning PF, Campion MA. A role-resource approach-avoidance model of job crafting: a multimethod integration and extension of job crafting theory. Acad Manage J. 2018;61(2):499–522. doi:10.5465/amj.2015.0604

9. Brykman KM, Raver JL. To speak up effectively or often? The effects of voice quality and voice frequency on peers’ and managers’ evaluations. J Organ Behav. 2021;42(4):504–526. doi:10.1002/job.2509

10. Burris ER. The risks and rewards of speaking up: managerial responses to employee voice. Acad Manage J. 2012;55(4):851–875. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.0562

11. Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Halbesleben JR. Productive and counterproductive job crafting: a daily diary study. J Occup Health Psychol. 2015;20(4):457–469. doi:10.1037/a0039002

12. Detert JR, Burris E. Leadership behavior and employee voice: is the door really open? Acad Manage J. 2007;50(4):869–884. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.26279183

13. Dierdorff EC, Jensen JM. Crafting in context: exploring when job crafting is dysfunctional for performance effectiveness. J Appl Psychol. 2018;103(5):463–477. doi:10.1037/apl0000295

14. Elliot AJ. The hierarchical model of approach-avoidance motivation. Motiv Emot. 2006;30(2):111–116. doi:10.1007/s11031-006-9028-7

15. Elliot AJ, McGregor HA, Gable S. Achievement goals, study strategies, and exam performance: a mediational analysis. J Educ Psychol. 1999;91(3):549–563. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.91.3.549

16. Fong CYM, Tims M, Khapova SN, Beijer S. Supervisor reactions to avoidance job crafting: the role of political skill and approach job crafting. Appl Psychol. 2021;70(3):1209–1241. doi:10.1111/apps.12273

17. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Market Res. 1981;18(1):39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104

18. Graen GB, Uhl-Bien M. Relationship-based approach to leadership: development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadersh Q. 1995;6(2):219–247. doi:10.1016/1048-9843(95)90036-5

19. Grant AM. Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(1):48–58. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.48

20. Grant AM, Parker S, Collins C. Getting credit for proactive behavior: supervisor reactions depend on what you value and how you feel. Pers Psychol. 2009;62(1):31–55. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.01128.x

21. Green SG, Anderson SE, Shivers SL. Demographic and organizational influences on leader–member exchange and related work attitudes. Organ Behav Hum Dec. 1996;66(2):203–214. doi:10.1006/obhd.1996.0049

22. Green SG, Mitchell TR. Attributional processes of leaders in leader-member interactions. Organ Behav Hum Perf. 1979;23(3):429–458. doi:10.1016/0030-5073(79)90008-4

23. Greenhaus JH, Parasuraman S, Wormley WM. Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Acad Manage J. 1990;33(1):64–86.

24. Griffin RW, Lopez YP. “Bad Behavior” in organizations: a review and typology for future research. J Manag. 2016;31(6):988–1005.

25. Hampson SE. When is an inconsistency not an inconsistency? Trait reconciliation in personality description and impression formation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(1):102–117. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.102

26. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach.

27. Huang X, Xu E, Huang L, Liu W. Nonlinear consequences of promotive and prohibitive voice for managers’ responses: the roles of voice frequency and LMX. J Appl Psychol. 2018;103(10):1101–1120. doi:10.1037/apl0000326

28. Kelley HH. The processes of causal attribution. Am Psychol. 1973;28(2):107–128. doi:10.1037/h0034225

29. Kelley HH, Michela JL. Attribution theory and research. Annu Rev Psychol. 1980;31(1):457–501. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.31.020180.002325

30. King RB, McInerney DM. The work avoidance goal construct: examining its structure, antecedents, and consequences. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2104;39(1):42–58. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2013.12.002

31. Kirkman BL, Chen G, Farh J-L, Chen ZX, Lowe KB. Individual power distance orientation and follower reactions to transformational leaders: a cross-level, cross-cultural examination. Acad Manage J. 2009;52(4):744–764. doi:10.5465/amj.2009.43669971

32. Lee JY, Lee Y. Job crafting and performance: literature review and implications for human resource development. Hum Resour Dev Rev. 2018;17(3):277–313. doi:10.1177/1534484318788269

33. Lichtenthaler PW, Fischbach A. A meta-analysis on promotion- and prevention-focused job crafting. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2019;28(1):30–50. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2018.1527767

34. Lyons P. The crafting of jobs and individual differences. J Bus Psychol. 2008;23(1–2):25–36. doi:10.1007/s10869-008-9080-2

35. MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff PM, Fetter R. Organizational citizenship behavior and objective productivity as determinants of managerial evaluations of salespersons’ performance. Organ Behav Hum Dec. 1991;50(1):123–150. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90037-T

36. Mäkikangas A. Job crafting profiles and work engagement: a person-centered approach. J Vocat Behav. 2018;106:101–111. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2018.01.001

37. Mayer DM, Ong M, Sonenshein S, Ashford SJ. The money or the morals? When moral language is more effective for selling social issues. J Appl Psychol. 2019;104(8):1058–1076. doi:10.1037/apl0000388

38. McClean EJ, Martin SR, Emich KJ, Woodruff CT. The social consequences of voice: an examination of voice type and gender on status and subsequent leader emergence. Acad Manage J. 2018;61(5):1869–1891. doi:10.5465/amj.2016.0148

39. Nielsen K, Abildgaard JS. The development and validation of a job crafting measure for use with blue-collar workers. Work Stress. 2012;26(4):365–384. doi:10.1080/02678373.2012.733543

40. Ohanian R. Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. J Advert. 1990;19(3):39–52. doi:10.1080/00913367.1990.10673191

41. Olson EM, Slater SF. The balanced scorecard, competitive strategy, and performance. Bus Horiz. 2002;45(3):11–16. doi:10.1016/S0007-6813(02)00198-2

42. Parker SK, Wang Y, Liao J. When is proactivity wise? A review of factors that influence the individual outcomes of proactive behavior. Annu Rev Organ Psych. 2019;6:221–248. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012218-015302

43. Peeters MC, Arts R, Demerouti E. The crossover of job crafting between coworkers and its relationship with adaptivity. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2016;25(6):819–832. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2016.1160891

44. Petrou P, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB. Crafting the change: the role of employee job crafting behaviors for successful organizational change. J Manag. 2016;44(5):1766–1792.

45. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

46. Posner RA. Social norms and the law: an economic approach. Am Econ Rev. 1997;87(2):365–369.

47. Radstaak M, Hennes A. Leader-member exchange fosters work engagement: the mediating role of job crafting. SA J Ind Psychol. 2017;43(1):1–11. doi:10.4102/sajip.v43i0.1458

48. Rastogi M, Chaudhary R. Job crafting and work‐family enrichment: the role of positive intrinsic work engagement. Pers Rev. 2018;47(3):651–674. doi:10.1108/PR-03-2017-0065

49. Rioux SM, Penner LA. The causes of organizational citizenship behavior: a motivational analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2001;86(6):1306–1314. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.6.1306

50. Rogiers P, Stobbeleir KD, Viaene S. Stretch yourself: benefits and burdens of job crafting that goes beyond the job. Acad Manage Discov. 2021;7(3):367–380. doi:10.5465/amd.2019.0093

51. Rudolph CW, Katz IM, Lavigne KN, Zacher H. Job crafting: a meta-analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. J Vocat Behav. 2017;102:112–138. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2017.05.008

52. Tims M, Bakker AB, Derks D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J Vocat Behav. 2012;80(1):173–186. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

53. Tims M, Bakker AB, Derks D. Examining job crafting from an interpersonal perspective: is employee job crafting related to the well-being of colleagues? Appl Psychol. 2015;64(4):727–753. doi:10.1111/apps.12043

54. Tims M, Derks D, Bakker AB. Job crafting and its relationships with person–job fit and meaningfulness: a three-wave study. J Vocat Behav. 2016;92:44–53.

55. Tims M, Parker SK. How coworkers attribute, react to, and shape job crafting. Organ Psychol Rev. 2020;10(1):29–54.

56. Tims M, Twemlow M, Fong CYM. A state-of-the-art overview of job-crafting research: current trends and future research directions. Career Dev Int. 2022;27(1):54–78. doi:10.1108/CDI-08-2021-0216

57. Turban DB, Jones AP. Supervisor-subordinate similarity: types, effects, and mechanisms. J Appl Psychol. 1988;73(2):228–234. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.73.2.228

58. Urbach T, Fay D. Leader member exchange in leaders’ support for voice: good relationships matter in situations of power threat. Appl Psychol. 2021;70(2):674–708. doi:10.1111/apps.12245

59. Urbach T, Fay D, Lauche K. Who will be on my side? The role of peers’ achievement motivation in the evaluation of innovative ideas. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2016;25(4):540–560. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2016.1176558

60. Wang H-J, Demerouti E, Le Blanc P. Transformational leadership, adaptability, and job crafting: the moderating role of organizational identification. J Vocat Behav. 2017;100:185–195. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2017.03.009

61. Wang HJ, Demerouti E, Bakker AB. A review of job-crafting research: the role of leader behaviors in cultivating successful job crafters. In: Parker SK, Bindl UK, editors. Proactivity at Work: Making Things Happen in Organizations. New York, USA: Routledge; 2016:77–104.

62. Whiting SW, Maynes TD, Podsakoff NP, Podsakoff PM. Effects of message, source, and context on evaluations of employee voice behavior. J Appl Psychol. 2012;97(1):159–182. doi:10.1037/a0024871

63. Wrzesniewsk A, Dutton JE. Crafting a job- Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad Manage Rev. 2001;26(2):179–201. doi:10.2307/259118

64. Xu E, Huang X, Ouyang K, Liu W, Hu S. Tactics of speaking up: the roles of issue importance, perceived managerial openness, and managers’ positive mood. Hum Resour Manage. 2020;59(3):255–269. doi:10.1002/hrm.21992

65. Zhang F, Parker SK. Reorienting job crafting research: a hierarchical structure of job crafting concepts and integrative review. J Organ Behav. 2019;40(2):126–146. doi:10.1002/job.2332

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2022 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.