Back to Journals » Patient Preference and Adherence » Volume 10

Individual difficulties and resources – a qualitative analysis in patients with advanced lung cancer and their relatives

Authors Sparla A, Flach-Vorgang S, Villalobos M, Krug K , Kamradt M , Coulibaly K, Szecsenyi J, Thomas M, Gusset-Bährer S, Ose D

Received 15 April 2016

Accepted for publication 7 July 2016

Published 3 October 2016 Volume 2016:10 Pages 2021—2029

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S110667

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 3

Editor who approved publication: Dr Johnny Chen

Anika Sparla,1 Sebastian Flach-Vorgang,1 Matthias Villalobos,2 Katja Krug,1 Martina Kamradt,1 Kadiatou Coulibaly,1 Joachim Szecsenyi,1 Michael Thomas,2 Sinikka Gusset-Bährer,2 Dominik Ose1,3

1Department of General Practice and Health Services Research, Heidelberg University Hospital, 2Internistische Onkologie der Thoraxtumoren, Thoraxklinik im Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg, Translational Lung Research Center Heidelberg (TLRC-H), Member of the German Center for Lung Research, Heidelberg, Germany; 3University of Utah, Department of Population Health Sciences, Health System Innovation and Research, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

Purpose: Lung cancer is a disease with a high percentage of patients diagnosed in an advanced stage. In a situation of palliative treatment, both patients and their relatives experience diverse types of distress and burden. Little research has been done to identify the individual difficulties and resources for patients with advanced lung cancer and their relatives. Especially, standardized questionnaire-based exploration may not assess the specific distressing issues that pertain to each individual on a personal level. The purpose of this qualitative study is to explore and compare individual difficulties and resources for lung cancer patients and their relatives within the palliative care context.

Methods: Data were collected by qualitative interviews. A total of 18 participants, nine patients diagnosed with advanced lung cancer (International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition, diagnosis C-34, stage IV) starting or receiving palliative treatment and nine relatives, were interviewed. Data were interpreted through qualitative content analysis.

Results: We identified four main categories of difficulties: communication and conflicts, home and everyday life, thinking about cancer, and treatment trajectory. In general, difficulties were related to interpersonal relationships as well as to impact of chemotherapy. Family, professional caregivers, and social life were significant resources and offered support to both patients and relatives.

Conclusion: Results suggest that patient and relative education could reduce difficulties in several areas. Patients seem to struggle with the fear of not having any perspective in therapy. Relatives seem to experience helplessness regarding their partner’s deterioration and have to handle their own life and the care work simultaneously. The most important resource for both patients and relatives is their family. In addition, professional lung cancer nurses support relatives in an emotional and organizational way. Intense supportive care for relatives should be standardized.

Keywords: inoperable lung cancer, palliative care, difficulties, resources, health services research, qualitative research

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common types of cancers in both males and females worldwide and at the same time the most common cause of cancer death.1,2 It has the poorest 5-year survival rate of ~15% in the US and Europe.3,4

Within the particular context of advanced lung cancer, it is important to include both patients and their family caregivers into the palliative care plan.5–7 Particular context means among others a very poor prognosis of approximately <1 year, which leads to existential burden and psychological distress.8–12 A majority of research uses quantitative methods to assess physical, psychological, and existential burden and distress. In addition to distress, physical symptom burden is high and well studied.5,13,14 In a study conducted with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer patients, fatigue, loss of appetite, shortness of breath, cough, pain, and blood in sputum were identified as common symptoms, as these were experienced by a high percentage of patients.15 Level of severity and amount of symptoms may differ depending on palliative therapy.13,16

Besides, lung cancer is an illness that carries a stigma, especially because of the strong association with smoking, and induces a feeling of shame and guilt.17,18 Recent studies have explored the physical, psychological, spiritual, and social well-being within the trajectory of illness for both patients and their relatives, so that we know better when key points in time of care are reached.19,20

Specific needs of lung cancer patients and their relatives exist, for example, the need for medical professionals and supportive care.14,21 In addition to exploration of needs, researchers recently focused on barriers of the use of supportive care and mental health services.22,23 Hence, existing health care structures are currently a focus of interest and reevaluation, especially within the palliative context.24,25 Improvements for patients with lung cancer and their carers in terms of psychological care have already been identified.26,27

However, little research has been done to identify individual difficulties and resources for patients with advanced lung cancer and their relatives.28–30

Especially, individual distressing issues may not be assessed by standardized questionnaire-based exploration.31 Furthermore, it is unclear whether existing findings are transferable to other cultural groups.30 These two aspects are important within the context of health services research and its increased relevance due to growing interest in reevaluation and improving the network for providing health care, since multiprofessional teams all over the world should be aware of the patients’ and their relatives’ individual situations.32 In particular, doctors breaking the news of a lung cancer diagnosis need to have insight into the patients’ background to develop a streamlined service tailored as far as possible.33

In order to explore this background further, we focus on individual difficulties and resources for both patients and their relatives. We evaluate and compare their situations and identify practical approaches in the range of palliative medicine.

Methods

Study design

The “Thoraxklinik” (Hospital for Thoracic diseases at the University of Heidelberg) is one of the largest lung cancer centers in Germany, receiving >1,000 newly diagnosed patients each year, 50% in metastatic stage and thus in need for palliative care. A qualitative study named “Aims of health care and individual quality of life for patients with limited prognosis” was started in cooperation with the Department of General Practice and Health Services Research (University Hospital Heidelberg) to improve palliative care in continuity. A qualitative, exploratory study design was chosen to allow intensive exploration and comparison of individual experiences and needs of both patients and relatives. The following general research question that is relevant for this study is explored within this analysis:

Which difficulties and resources for patients and relatives can be identified – where might health care find potential for an improved individual quality of life for both patients and relatives?

Ethical approval was given by the ethics committee of the University Hospital Heidelberg (S-589/2014). All participants gave their written informed consent, and their pseudonymization and confidentiality were ensured throughout the study.

Study sample

All patients with International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition diagnosis C-34, stage IV, and their relatives were potential participants for this study. Further eligibility criteria were 18 years of age or older, absence of acute psychiatric illness as well as of moderate to severe form of dementia, and constricted ability to communicate. Patients were recruited from the Thoraxklinik Heidelberg’s patient master data. Almost all were receiving palliative chemotherapy and were asked for their interest in study participation by a lung cancer specialist. As they were often accompanied by relatives, relatives were asked at the same time. Potential participants were given detailed information about the study before consenting to take part. Next time they came to the hospital, they gave informed consent before having the interview.

Data collection

Semi-structured, pilot-tested interview guides built the ground for conducting interviews with patients and relatives. Themes and questions of these interview guides were based on theoretical considerations, expert discussions, and an extensive literature review in relation to the burdensome nature of the disease, including physical and psychological burden. There was the possibility to ask open questions allowing participants to explore newly arising issues, so that the principle of both theory-driven and open qualitative research was taken into account. It was planned to conduct at most 32 interviews, 16 with patients and 16 with relatives, but only if saturation of data was not reached before. The duration of the interviews ranged from 30 minutes to 90 minutes. The interviews with patients and relatives were conducted separately to minimize response bias by experienced researchers and doctoral candidates from the Department of Health Service Research, in a private room in the hospital. All interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

The material, transcribed texts of patients’ and relatives’ interviews, including pseudonymization, was fundamental for the approach to qualitative content analysis, according to Mayring, used in this study.34,35 The software ATLAS.ti (version 7.5) permitted to edit and analyze the texts in a structured way. A search grid (category system) was formed, on the one hand, based on the interview guides and, on the other hand, adapted during the process if the data showed new or additional information that did not fit into the category system yet. This represents the approach of both deductive and inductive development and application of categories.35 While analyzing the first interviews step by step, the research team (two doctoral candidates in medicine, one health services researcher, and one psychologist) developed a system of categories and subcategories that were clearly defined and linked with representative examples from the original texts. We started using the deductive categories and subcategories based on the semi-structured interview guide. In the course of our analysis, a majority of subcategories and categories were developed inductively, according to the focus of this article. Within our multiprofessional research team, all aspects were discussed and further modified until a consensus of the final category system was achieved. Then, we analyzed as many interviews until saturation of data was reached, that is, there was no additional information gained.

Results

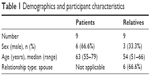

From March until July 2015, 18 interviews with a total of nine patients and nine relatives were conducted. The patients’ age ranged between 55 years and 79 years (median 63 years) and the relatives’ age ranged between 51 years and 66 years (median 54 years) (Table 1).

| Table 1 Demographics and participant characteristics |

Difficulties and fields of problems

We identified four main categories: “communication and conflicts”, “home and everyday life”, “thinking about cancer”, and “treatment trajectory”. Often difficulties were related not only to interpersonal relationships but also to patient-related aspects, such as physical weakness that led, for example, to limited self-supply and life at home. Generally, we found a similar amount of individual problems in patients and relatives (Table 2). Each subcategory is described respectively for the patients’ aspects, followed by the relatives’ aspects.

| Table 2 Difficulties and fields of problems |

Communication and conflicts

In some cases, patients struggled with their life as a smoker. They were not sure if smoking was a mistake and reported a permanent preoccupation with this topic. Accusation by family members was experienced as an additional burden.

On the other hand, patients experienced avoidance by their family concerning talking about deterioration or death, which probably hindered them to be prepared for it in the future.

We don’t talk about dying at all. I’m not even allowed to come up with it, they will immediately say “Father (well) […] it goes on”. [Pat. 3]

Relatives found it difficult to cope with opinions and advices from others. They saw their own negative mood founded by others’ predications about the patient’s limited lifetime and did not want to hear further opinions anymore. Another perspective was represented by the impression that everyone who knew about the diagnosis tried to give advice in order to help patient and relative, which then led to an information overflow. As a result, this was refused as well by not talking about the illness or by not taking the advices anymore.

[…] When it is disclosed in your family or social life, everyone comes up with 1,000 tips and then you first have to say: “Hey guys, thanks a lot, but information overflow.” I stopped this completely […]. [Rel. 5]

Conflicts between patients and relatives arose out of different ideas about therapy, for example, the different importance of alternative medicine and disagreement concerning the choice of the general practitioner. It became apparent that patients were often confident about the general practitioner they were used to, while their partners rather felt unhappy, for example, if they did not have sympathy for or confidence in him/her.

[…] In fact at home it comes to quarrel, she says I’ll finally have to choose another general practitioner, I say I feel to be in good hands. [Pat. 8]

Least social isolation represented a subcategory, which was mentioned only by relatives: some relatives experienced a withdrawal of friends since diagnosis that led to regret and lack of understanding, another difficulty they had to handle.

But there are friends, aren’t there? Yes, not many, some are afraid I guess, I don’t even know, since my husband became ill, contact was interrupted. [Rel. 1]

Home and everyday life

The impact of chemotherapy in general, but weakness in particular, was an important factor influencing the patients’ everyday life. Patients were highly affected by the lack of physical power as they were tired and not able to perform certain activities anymore, such as sports. Physical weakness also affected their possibility of caring for themselves at home.

Relatives witnessed the physical weakness and impact of chemotherapy on the patients. Often, they felt helpless regarding their partner and sometimes they were not able to understand why patients had such big problems with eating and appetite.

It became apparent that next to physical weakness, patients had to handle mood swings as a symptom of psychological weakness.

It depends on your state, you know? If you feel miserable you’re also more irritable. [Pat. 5]

Patients’ psychological weakness was realized by relatives too, but they rarely talked about their own emotions. In this regard, mood swings influenced the mood of relatives as well, as they were aware of situations where patients became extremely stressed and how their behavior was then, for example, after having received chemotherapy.

Which situation means horror in particular? In fact the day of chemotherapy, […] then he suffers from strong headache, becomes aggressive in parts, yeah, these mood swings. [Rel. 3]

In case of advanced deterioration due to illness, patients were confronted with the care of nursing services. They found it difficult to accept because it stood for further worsening.

It became apparent that relatives saw that patients had problems to accept a nursing service and the fact of being dependent from others in general. However, they appreciated it.

The following two findings were mentioned by patients only:

Another difficult aspect was represented by “getting along alone”. While some patients struggled with the doctor’s advice not to live alone anymore as they wished to live at home, other patients feared the time alone facing their problems, waiting for their partners to return from work. Furthermore, there were financial problems patients had to think about. This sometimes led to a kind of pressure to get well again, for example, if the house was not yet payed and lower pensions due to early retirement would not be high enough to settle debts.

[…] In case of early retirement, it would be very difficult to keep the house and to compensate a loss of the practice when she becomes ill, that wouldn’t work, for sure. So there is a certain pressure to get well again. [Pat. 8]

The following two findings were mentioned by relatives only:

A further difficulty was represented by the fact that relatives had to manage their own life, for example, their job or other plans at the same time. At least, poor health presented another difficulty along with caring for the patient.

Thinking about cancer

It was evident that worry about deterioration was a permanent topic within the patients’ thinking. Particularly at times after having received chemotherapy and waiting for the next results of follow-up, it was hard to bear the fear of not having a perspective in therapy anymore.

Relatives worried about deterioration while waiting for the results of follow-up, too. This even led to somatic symptoms for both patients and relatives, for example, abdominal pain.

Another difficulty in thinking about cancer was the experience with others who suffered from lung cancer and died. Patients became aware of their own physical worsening and felt depressed as a consequence.

He fought for four years. When he worked before, he had twice of my figure – and in the end … the same as I now. – He was simply used up. – And this dragged me down for a few days. [Pat. 8]

Besides, some relatives thought about earlier deaths within the family and realized that they feared the loss of their partner.

The following two findings were mentioned by relatives only:

Uncertainty about the responsibility concerning care for the patient at life’s end led to difficulties with a decision. Few relatives were not sure if they were obliged to accompany the patient till he/she dies, for example, if there did not exist an affectionate relationship.

On the other hand I think, I can’t let her go alone, after all the time close together. I really don’t know how to handle it. [Rel. 2]

At least, the immediate temporal sequence of receiving bad news represented another difficulty to relatives. They stressed that it was hard to handle diagnosis and the following diagnostic findings within a few months.

Treatment trajectory

Both patients and relatives brought up the difficulties of long waiting hours while receiving chemotherapy and of the discontinuity of attachment figures. While long waiting hours especially led to worsening of psychological weakness, discontinuity of the doctors raised upset. Both patients and relatives doubted whether the quality of treatment could be sustainable in this situation.

20 people, caring for one patient, they’re not able to know all the time what should, or what might be allowed […] [Rel. 7]

Resources and support

Resources and support led to an easier way of handling cancer as well as to a better situation of care. We identified three categories, “family”, “professional caregivers”, and “social life” that were of significance and gave support to both patients and relatives (Table 3). Each subcategory is described respectively for patients’ aspects, followed by the relatives’ aspects.

| Table 3 Resources and support |

Family

Patients commonly emphasized the meaning of family in several ways. On the one hand, family members encouraged patients, and on the other hand, they were simply there for them.

Relatives saw an increase of consideration within their families in general.

Closeness to family, especially to their partners, meant much to patients, too. It became apparent that some patients appreciated the possibility to join their partner at the hospital.

She [wife] is happy if it’s possible to stay nearby and I’m happy for her to stay nearby, this was like a blessing for the week now. [Pat. 1]

According to that, relatives realized the patients need for closeness and complied with it.

Further, family members attended patients’ therapy, for example, in paying attention to take medicine. Children supported the patient and his/her partner in an organizational way by attending the house or flat. Relatives also appreciated the support and given comfort of their family.

In contrast, they were aware of their own part, which was to support the patient.

Professional caregivers

Patients appreciated the dedication of the palliative care unit nursing services. It became apparent that especially their prompt accessibility was important, for example, in case of managing the possibility for one patient’s spouse to stay together in the palliative care unit. Furthermore, relatives had another perspective of nursing services and support. Some experienced that nurses came to them and were interested in the relatives’ worries, which meant much to them. They were also relieved to get some information about care in general, in case they had not gained experience with this topic yet.

One of them [nurse] today: ‘You know there are nursing services, [they are] acquirable day and night.’ […] you’re not informed about these topics, especially if you haven’t had it in your family yet. [Rel. 1]

Patients also appreciated the option to talk to psychologists.

In parallel, relatives considered talking to a psychologist within the hospital, guessing that he or she was more professional in terms of oncology than maybe their own psychologist was able to be.

At least, patients were happy to have a physician as attachment figure within the hospital. Both patients and relatives were thankful in case of standing to benefit from the general practitioner. It became apparent that his or her support in the form of organization of appointments was very important for relatives in particular.

[…] Then we ended up at this lady and I have to admit her medical attendance was optimal, she tried everything within human power before, to get the diagnostic findings as fast as possible. [Rel. 9]

Social life

Patients were aware of the support of friends, for example, sports club friends, which was very important for them. Relatives also benefited from their social life and contacts. Especially, openness was important for them, both toward friends and neighbors.

Some patients sought to take part in sports activities as they did before diagnosis, for example, swimming. Relatives appreciated the possibility of special cancer sports classes, as they often wanted to help to improve the patients’ constitution. In case of commiseration through colleagues, patients felt to be needed, and this led to thankfulness and happiness.

[…] I was very pleased, the colleagues wrote me a card […]. This […] points to me that I’m still wanted in my position. [Pat. 8]

While some relatives still worked and were thankful that colleagues were amicable and afforded a flexible work plan (so that they were able to keep appointments together with the patient), some already received pension and were glad about this because they did not need to arrange work next to the care for the patient.

Discussion

The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore and compare individual difficulties and resources for patients and their relatives within the palliative care context. Our study allowed an intensive and individual examination from the participants’ view. For this study, we focused on two topics, which were regularly brought up by patients and relatives: difficulties and resources within the context of handling the advanced illness.

We were able to detect a high consent between our qualitative findings and findings in previous studies that used quantitative mixed methods and qualitative approaches to put out aspects of resources, psychological burden, existential burden, symptom burden, and distress.12,30,31 However, there were some issues in our study that seemed to be newly discovered:

Resource for relatives: Pension and flexible work plan.

Difficulties for relatives: Listen to opinions and advices, poor health, uncertainty about the responsibility concerning care for the patient at life’s end, immediate temporal sequence of receiving bad news.

Difficulties for patients: Getting along alone, financial aspects led to pressure to get well again.

Difficulties for both: Thoughts about deaths of others, conflicts concerning alternative medicine, and the choice of a general practitioner.

Hence, we are able to acknowledge that individual distressing issues may not be assessed by standardized questionnaires and may also vary between qualitative studies’ findings.31

Our results converge with prior research, where family, friends, and health care professionals are identified as most important resources for people living with cancer. On the one hand, families play a key role in providing care and support.30,36 On the other hand, social support is known as one of the most important resources in adapting to cancer in general.37 Especially in case of advanced lung cancer, patients and their relatives rely on family and friends for support in managing emotions and physical symptoms – they also benefit from interactions with health care professionals.30,38 The fact that both our study and an independent qualitative study by Mosher et al (in another country and cultural background) found a resource in lung cancer nurses not only for patients but also for relatives strengthens the relatives’ need for intense supportive care in particular.39 Hence, we emphasize the requirement for early palliative care for caregivers of patients with advanced cancer.40

Researchers found a multiplicity of factors that lead to distress in patients with advanced lung cancer and their relatives.9,12,20,31,39,41 In the context of everyday life, weakness and fatigue are cancer-related symptoms that have impact on quality of life and on the ability to carry out normal activities.15,29 Fatigue even remained the symptom causing the greatest distress in advanced lung cancer patients.42

In our study, patients suffered from physical weakness, too. They were not able to be as active as before their diagnosis, for example, concerning the performance of tasks of daily life, which even led to desperation. These results also converge with the findings of Chochinov et al,12 as they state functional limitations as problematic for terminal ill cancer patients.

In addition to that we found the difficulty to admit end-of-life care in terms of outpatient nursing service from the patients’ side. Berterö et al stated that patients had a hard time admitting to themselves that they were seriously ill after receiving a diagnosis of inoperable lung cancer.17 According to that, Chochinov et al assessed existential well-being by a psychometrically sound measure.12 In this study, patients experienced, for example, the feeling of not having control and of being a burden to others. Thus, we see an analogy concerning qualitative findings and quantitative measured aspects.

Hence, we think that end-of-life care should be addressed in an open way to find an individual solution for the whole family. As end-of-life discussions are associated with less aggressive medical care near death and earlier hospice referrals and at the same time not associated with higher rates of major depression disorder or more worry in patients, openness seems to be a reasonable way on the whole.43

According to this, the team should be aware of the difficulty that sometimes it comes to avoidance concerning talking about dying within some families, a finding that has been identified in other studies.30,44 In contrast, it could be stated that symptomatic patients tended to report avoiding negative emotions.30 Thus, avoidance may be used by patients as well as relatives.

Stigma, triggered by the strong association of lung cancer and smoking in connection with the feeling of shame and guilt, could be found again within our subcategory “accusation”.17,18 We think that this aspect contributes furthermore to high psychological burden in some patients.

Our results converge with the results of Mosher et al, who found time-consuming efforts to manage the patient’s emotional reactions to the illness and coordinating the patient’s medical care as key challenges of family caregivers in coping with their family member’s advanced lung cancer.39 In our study, relatives found it difficult to experience patients’ mood swings in a situation of receiving palliative chemotherapy.

Another difficulty we found was the negative influence of advices of others on the mood of relatives. We think it would be important to consider these topics within the psycho-oncological care. Further, we found helplessness in relatives, especially within the context of the patient’s loss of appetite. It is known that assessing adequate nutrition is one of the most challenging problems for nurses, their patients, and patient’s families.45 Everyone should be given detailed information about cachexia to prevent overreactions that may lead to conflicts within the families.

Dealing with fears about disease spreading is identified as an unmet need of patients with lung cancer and also found to be a main component of distress for both patients and partners.14,41 Concerning our subcategory “worry about deterioration”, we furthermore identified the fear of not having any perspective in therapy as a difficulty for patients and relatives, and we think it should be scrutinized in a critical way. It is stated that both patient and carer may have another idea about palliative treatment and its aims in contrast to current evidence.46–48

Finally, we found difficulties within treatment trajectory. Patients and relatives criticized long waiting hours within the hospital as an additional burden, as well as the discontinuity of doctors due to rotation plan. Recent studies found hospital stays as a distressing concern (iatrogenic distress: lack of continuity in doctors and nurses), as well as a lack of support while waiting for test results and start of treatment.31,49 Given the situation of various forms of burden due to the illness, it should be a purpose to reduce these difficulties within the hospital. Patients and relatives should have the possibility to profit from individual and continuous care, which is absolutely essential regarding the sensitive issues they have to discuss with the multiprofessional team.

Conclusion

Our findings can contribute to important information concerning the individual situation of patient and carer within a palliative care unit and a focus on care based on the model of early palliative care.

In general, difficulties arise out of the impact of palliative cancer-specific therapy as well as out of interpersonal relationships. Patients seem to struggle with their weakness, mood swings, and the fear of not having any perspective in therapy. Relatives seem to experience helplessness regarding their partner’s deterioration and have to handle their own life in parallel to caring. Results suggest that patient and relative education could reduce difficulties in several areas.

The most important resource for both patients and relatives is their family. Besides, professional lung cancer nurses support relatives in an emotional and organizational way.

Implications for praxis

Several aspects within our findings report psychological burden for both patients and relatives. Hence, improvements in terms of the use of palliative care services and the use of mental health services are important. Further research should find out in particular how these improvements could be reached.

We should make patients and relatives aware of the bandwidth of reactions they might get from the part of family members and the social surrounding on communicating the diagnosis. Information about therapy and their impact on the patients’ physical and psychological health should always be given in an honest way, to prevent the fear of not having any more options. There are several individual difficulties patients and relatives have to face, and therefore, a continuing counseling should be offered to both of them. Further research is needed to explore if continuity of attachment figures within the hospital can lead to patients’ and relatives’ satisfaction and may lead to an improved quality of life.

End-of-life care remains a difficult topic because patients and relatives may not always be prepared to talk about it. Physicians should be educated in particular to be able to talk about this topic in an open way, so that an individual solution for each family can be found. Helplessness of relatives should be identified of importance for multiprofessional team comparably to the patients’ fears and symptom burden. There should be an awareness that families may not be used to palliative care and the possibilities of support offered in the space of their home. An early evaluation of these circumstances should be standardized in a palliative care unit, so that especially families with a lack of knowledge and resources can be identified and supported from diagnosis onward.

Strengths and limitations

As patients with advanced lung cancer and their relatives experience psychological, physical, and existential burden after diagnosis and during palliative treatment, it is essential to involve them early in reevaluation of treatment in order to sustain their individual quality of life. Consequently, exploring their difficulties and resources to handle cancer was an important step to gain an overarching comprehension of their individual situation within the existing health care structure. The study was conducted by a multiprofessional team of researchers (medicine, health services research, psychology) providing for a broad perspective during design and analysis stages.

Though, the findings must be interpreted with caution as one limitation of the study was that interviewers varied. Despite the semi-structured interview guide that was used, there may be different focuses, also due to the potential to ask open questions.

Another limitation of this study is represented by the fact that there was a high amount of subcategories so that it was not realizable to give one quote for each subcategory within the limited size of this article. Readers may consider reading the Supplementary materials to gain a detailed insight into the quotes.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global Cancer Statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(2):74–108. | ||

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5–29. | ||

Dela Cruz CS, Tanoue LT, Matthay RA. Lung cancer: epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clin Chest Med. 2011;32(4):605–644. | ||

de Angelis R, Sant M, Coleman MP, et al; EUROCARE-5 Working Group. Cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007 by country and age: results of EUROCARE-5 – a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(1):23–34. | ||

Oechsle K, Goerth K, Bokemeyer C, Mehnert A. Symptom burden in palliative care patients: perspectives of patients, their family caregivers, and their attending physicians. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(7):1955–1962. | ||

World Health Organization. WHO | WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Accessed November 27, 2015. | ||

Hui D, de La Cruz M, Mori M, et al. Concepts and definitions for “supportive care,” “best supportive care,” “palliative care,” and “hospice care” in the published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(3):659–685. | ||

Yates P, Schofield P, Zhao I, Currow D. Supportive and palliative care for lung cancer patients. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5(5):S623–S628. | ||

Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10(1):19–28. | ||

Morita T, Kawa M, Honke Y, et al. Existential concerns of terminally ill cancer patients receiving specialized palliative care in Japan. Supportive Care Cancer. 2004;12(2):137–140. | ||

Prasse A, Waller C, Passlick B, Müller-Quernheim J. Lungenkrebs aus Sicht der Inneren Medizin und Chirurgie [Lung cancer from internal medicine and surgery point of view]. Radiologe. 2010;50(8):662–668. German. | ||

Chochinov HM, Hassard T, McClement S, et al. The landscape of distress in the terminally ill. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(5):641–649. | ||

Wang XS, Shi Q, Williams LA, et al. Prospective study of patient-reported symptom burden in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer undergoing proton or photon chemoradiation therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(5):832–838. | ||

Liao Y-C, Liao W-Y, Shun S-C, Yu C-J, Yang P-C, Lai Y-H. Symptoms, psychological distress, and supportive care needs in lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(11):1743–1751. | ||

Iyer S, Roughley A, Rider A, Taylor-Stokes G. The symptom burden of non-small cell lung cancer in the USA: a real-world cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(1):181–187. | ||

Wang XS, Fairclough DL, Liao Z, et al. Longitudinal study of the relationship between chemoradiation therapy for non-small-cell lung cancer and patient symptoms. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(27):4485–4491. | ||

Berterö C, Vanhanen M, Appelin G. Receiving a diagnosis of inoperable lung cancer: patients’ perspectives of how it affects their life situation and quality of life. Acta Oncol. 2008;47(5):862–869. | ||

Chapple A, Ziebland S, McPherson A. Stigma, shame, and blame experienced by patients with lung cancer: qualitative study. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1470. | ||

Murray SA, Kendall M, Grant E, Boyd K, Barclay S, Sheikh A. Patterns of social, psychological, and spiritual decline toward the end of life in lung cancer and heart failure. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(4):393–402. | ||

Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Grant L, Highet G, Sheikh A. Archetypal trajectories of social, psychological, and spiritual wellbeing and distress in family care givers of patients with lung cancer: secondary analysis of serial qualitative interviews. BMJ. 2010;340:c2581. | ||

Northouse L, Williams A-L, Given B, McCorkle R. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1227–1234. | ||

Frankel ES, Evans TL, Burgess J, et al. Supportive/palliative care use among patients with lung cancer: rates and barriers. ASCO Mtg Abstr. 2011;29(15 suppl):e19608. | ||

Mosher CE, Winger JG, Hanna N, et al. Barriers to mental health service use and preferences for addressing emotional concerns among lung cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2014;23(7):812–819. | ||

Temel Jennifer S, Greer Joseph A, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742. | ||

Sun V, Grant M, Koczywas M, et al. Effectiveness of an interdisciplinary palliative care intervention for family caregivers in lung cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(20):3737–3745. | ||

van den Hurk DG, Schellekens MP, Molema J, Speckens AE, van der Drift MA. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for lung cancer patients and their partners: results of a mixed methods pilot study. Palliat Med. 2015;29(7):652–660. | ||

Ryan PJ, Howell V, Jones J, Hardy EJ. Lung cancer, caring for the caregivers. A qualitative study of providing pro-active social support targeted to the carers of patients with lung cancer. Palliat Med. 2008;22(3):233–238. | ||

Persson C, Sundin K. Being in the situation of a significant other to a person with inoperable lung cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(5):380–388. | ||

Sarna L. Women with lung cancer: impact on quality of life. Qual Life Res. 1993;2(1):13–22. | ||

Mosher CE, Ott MA, Hanna N, Jalal SI, Champion VL. Coping with physical and psychological symptoms: a qualitative study of advanced lung cancer patients and their family caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(7):2053–2060. | ||

Tishelman C, Lövgren M, Broberger E, Hamberg K, Sprangers MAG. Are the most distressing concerns of patients with inoperable lung cancer adequately assessed? A mixed-methods analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(11):1942–1949. | ||

Lohr KN, Steinwachs DM. Health services research: an evolving definition of the field. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(1):15–17. | ||

Yardley SJ, Davis CL, Sheldon F. Receiving a diagnosis of lung cancer: patients’ interpretations, perceptions and perspectives. Palliat Med. 2001;15:379–386. | ||

Mayring P. Qualitative inhaltsanalyse [Qualitative content analysis]. Forum Qual Soz. 2000;1(2):1–10. German. | ||

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. | ||

Given BA, Given CW, Kozachik S. Family support in advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51(4):213–231. | ||

Mehnert A, Lehmann C, Cao P, Koch U. Die Erfassung psychosozialer Belastungen und Ressourcen in der Onkologie – Ein Literaturüberblick zu Screeningmethoden und Entwicklungstrends [Identification of psychosocial burden and resources in oncology – a literature review of screening methods and trends]. Psychother Psych Med. 2006;56:462–479. German. | ||

Maguire P, Pitceathly C. Improving the psychological care of cancer patients and their relatives. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55(5):469–474. | ||

Mosher CE, Jaynes HA, Hanna N, Ostroff JS. Distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients: an examination of psychosocial and practical challenges. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(2):431–437. | ||

Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD, et al. Benefits of early versus delayed palliative care to informal family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: outcomes from the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(13):1446–1452. | ||

Haun MW, Sklenarova H, Villalobos M, et al. Depression, anxiety and disease-related distress in couples affected by advanced lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2014;86(2):274–280. | ||

Tishelman C, Petersson L-M, Degner LF, Sprangers MAG. Symptom prevalence, intensity, and distress in patients with inoperable lung cancer in relation to time of death. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(34):5381–5389. | ||

Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–1673. | ||

Badr H, Taylor CLC. Social constraints and spousal communication in lung cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15(8):673–683. | ||

Del Ferraro C, Grant M, Koczywas M, Dorr-Uyemura LA. Management of anorexia-cachexia in late stage lung cancer patients. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2012;14(6):397–402. | ||

Burns CM, Broom DH, Smith WT, Dear K, Craft PS. Fluctuating awareness of treatment goals among patients and their caregivers: a longitudinal study of a dynamic process. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(2):187–196. | ||

Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2319–2326. | ||

Mitera G, Zhang L, Sahgal A, et al. A survey of expectations and understanding of palliative radiotherapy from patients with advanced cancer. Clin Oncol. 2012;24(2):134–138. | ||

Murray SA, Boyd K, Kendall M, Worth A, Benton TF, Clausen H. Dying of lung cancer or cardiac failure: prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers in the community. Br Med J. 2002;325(7370):929. |

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2016 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.