Back to Journals » HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care » Volume 13

Incidence of Mortality and Its Predictors Among HIV Positive Adults on Antiretroviral Therapy in University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia

Authors Teshale AB , Tsegaye AT , Wolde HF

Received 31 October 2020

Accepted for publication 6 January 2021

Published 13 January 2021 Volume 2021:13 Pages 31—39

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S289794

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single anonymous peer review

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Bassel Sawaya

Achamyeleh Birhanu Teshale, Adino Tesfahun Tsegaye, Haileab Fekadu Wolde

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Institute of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia

Correspondence: Achamyeleh Birhanu Teshale Email [email protected]

Background: Despite the accessibility and higher coverage of antiretroviral therapy (ART), HIV/AIDS is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in low- and middle-income countries. Ethiopia also shares the high burden of HIV/AIDS-related morbidity and mortality. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the incidence of mortality and its predictors among adult HIV patients on ART in the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, northwest Ethiopia.

Patients and Methods: A retrospective follow-up study was conducted from January 2015 to January 2019 at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital. A total of 475 patients who were on follow-up in this Hospital were included. The Cox proportional hazard model was fitted to assess the predictors of mortality. Both crude and adjusted hazard ratio (AHR) with their 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated to show the strength of association. In multivariable analysis, variables with a P-value < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant predictors of mortality.

Results: In this study, a total of 45 (9.5%) patients died with an incidence rate of 5.3 [95% CI: 3.4– 7.1] per 100 person-years of observation. In the multivariable Cox regression analysis, the last known WHO stage III/IV [AHR= 15.02; 95% CI: 5.79– 38.92], being anemic at baseline [AHR = 2.21; 95% CI: 1.02– 4.78], and fair last known adherence level [AHR = 3.29; 95% CI: 1.39– 7.78] were found to be significant predictors of mortality.

Conclusion: In this study, the incidence of mortality was relatively high. The rate of mortality may be minimized by paying particular attention to individuals with advanced WHO stage, anemia at the baseline, and those with adherence problems.

Keywords: mortality, antiretroviral therapy, HIV/AIDS

Background

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) continues to be a major global public health issue with 37.9 million people living with HIV, by the end of 2018 and taking over 32 million lives to date.1 Even though Sustainable Development Goal 3 explicitly calls for the end of the HIV epidemic by 2030, still it is alarmingly increased thought out the globe.2

Despite the accessibility and higher coverage of antiretroviral therapy (ART) with around 24.5 million people take antiretroviral therapy in the world, HIV/AIDS is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa and other low and middle-income countries.1,3,4 Sub-Saharan African countries share the highest HIV epidemic with 75% of deaths and 65% of new infections in 2017 and 71% of people living with HIV.3,4 East and Southern Africa account for only 6.2% of the world’s population but the highest number of people (54%) living with HIV, about 800,000 new infections, and around 310,000 AIDS-related deaths are from these regions.5,6

The proportions of AIDS-related mortality vary between African countries ranging from 4.5% in Uganda to 29.7% in Tanzania.7–12 Ethiopia also shares the high burden of HIV/AIDS-related mortality ranging from 5.9% in Goba Hospital to 18% in the Oromia region.13–19

Prior studies revealed sociodemographic, clinical and treatment related factors such as age,20 sex,9,10,21 educational level,15,21 marital status,9,19 body mass index (BMI),12,18,19 opportunistic infections (OIs),18 world health organization (WHO) clinical stage,9,16–19 isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT),15,18 Hemoglobin (Hgb) level,9,12,19,21,22 functional status,16,17,19 CD4 count,9,16,19,22 disclosure status,17 and adherence20,22 are significantly associated with mortality in adult HIV/AIDS patients on ART.

Studies have reported both baseline socio-demographic and clinical factors as predictors of mortality among HIV patients after ART initiation. However, there is no updated information on these factors, which contribute to the mortality of adult HIV-infected patients after ART initiation, in the study area. Besides, some important variables such as disclosure status, the current adherence level, and caregiver status are not assessed by most of the previous studies. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the predictors of mortality among adult HIV patients on ART in the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, northwest Ethiopia. The findings of this study will provide empirical evidence for program planners, decision-makers, and ART program implementers at different levels by enabling them to access predictors of survival/mortality after the advancement of ART. Moreover, it will have paramount importance in providing baseline information that will assist in the development of a system for tracking adherence, improving quality of life, and survival.

Patients and Methods

Study Design, Study Area, and Period

A retrospective follow-up study was conducted from January 2015 to January 2019 at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Gondar, northwest Ethiopia. The Hospital is found in Gondar town, which is one of the historical cities in Ethiopia with an estimated population of 153,914. Gondar town is located 421 kilometers far from the capital city of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa with a traveling distance of 727 kilometers. The city is also 172 kilometers (traveling distance) far from the capital city of the Amhara region, Bahirdar. The hospital, which is a leading referral hospital in northwest Ethiopia, serves an estimated five million people. The ART service is one of the services given by this hospital and a review of the hospital’s medical records showed that more than 5500 patients are being on ART and more than 5200 of them are adults.

Source and Study Population

The source population was all adult patients on ART who are on follow-up in University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital and our study population were those adult HIV positive patients on ART during the study period. Those adults who had at least one follow-up visit were included in our study and those with unknown ART initiation and outcome date, patients who initiated treatment outside the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, and women who were pregnant were excluded from this study.

Sample Size and Sampling Procedure

The sample size was calculated using the Schoenfeld formula which is the preferred method of sample size determination for survival analysis.23 The calculation was based on the results found from a retrospective follow-up study conducted in the Somali region of Ethiopia,19 by considering three independent variables (marital status, WHO clinical stage, and BMI). Then the highest sample size was 475 with the number of expected events to be forty-seven (Table 1). Concerning the sampling technique, we employed a simple random sampling technique by using their medical registration number after taking it from the ART database, using a computer-generated random number.

|

Table 1 Sample Size Calculation |

Variables of the Study

The dependent variable was time from ART initiation to mortality (which was the event of interest). After searching of literatures, the independent variables included for our study were classified as sociodemographic, clinical, and treatment-related factors. The sociodemographic factors included were; age, sex, marital status, religion, educational status, occupation, household size, having caregiver, and disclosure status. Of the clinically and treatment-related factors; months on ART, baseline OIs, baseline BMI, baseline and last known WHO stages, baseline CD4 count, baseline Hgb level, history of ART treatment change, history of ART medication side effect, baseline IPT and CPT prophylaxis, baseline functional status, and last known adherence were incorporated as independent variables.

Operational Definition

Event: Time to the occurrence of mortality, which was recorded as the death of the patient in the follow-up chart.

Censoring: Those patients who were transferred to other institutions, lost from care, or still on follow-up at this hospital at the end of the study period.

Functional status: This is defined based on the national ART guideline as; working (capable of performing ordinary work inside or outside the home), ambulatory (capable of performing daily living activities), and bedridden (incapable of performing daily living activities).24

Adherence: This means adherence to ART drugs and is estimated using three levels; good when patient adherence level is as high as 95% (of 30 doses missed as low as 2 doses), fair when patient adherence level is 85–94% (of 30 doses missed as low as 3–4 doses), and poor when patient adherence level is as high as 84% (of 30 doses missed as low as 6 doses).24

ART side effect: Those patients who had at least one ART related adverse event such as nausea, fatigue, anemia, abdominal pain, or other adverse events since ART initiation and recorded in the follow-up chart.

Data Collection Procedure and Quality Assurance

We searched data collectors (a total of four physicians working at the ART clinic) and a supervisor (who was a medical doctor working at the ART clinic) after designing the data extraction sheet according to our study goals. The principal investigator trained the data collectors and supervisors about the data collection process. A pre-test using 5% of our sample was performed in a similar setting before the actual data collection and modifications were considered based on the pre-test result. The supervisor and principal investigator had undertaken frequent and timely supervision of data collectors. During data collection, the principal investigator and supervisor checked out the collected data for its completeness.

Data Processing and Analysis

The data were entered into EpiData version 3.1 software and exported into STATA version 14 software. Descriptive statistics including tables and graphs were done to describe the characteristics of the study participants. The Log rank test and Kaplan–Meier survival curve were done to assess whether there was a survival difference between the categories of each independent variable. Cox proportional hazard model was fitted and the overall model fitness was checked by plotting Nelson-Aalen cumulative hazard with Cox-Snell residual. The proportional hazard assumption was checked by interacting each covariate with time and using the Schoenfeld residual test. Those variables with a p-value of <0.20 in the bivariable analysis were eligible for multivariable cox regression analysis. Both crude and adjusted hazard ratio with their 95% Confidence interval was calculated to show the strength of association. In multivariable analysis, variables with a P-value of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Sociodemographic, Clinical and Treatment-Related Characteristics of Respondents

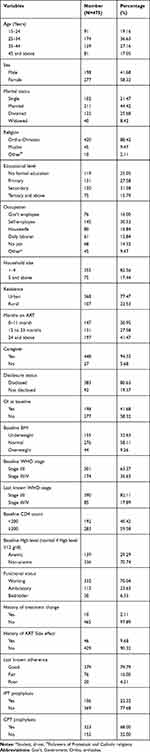

In this study, we used a total sample of 475 adult HIV patients who were on ART. The majority (36.63%) of the respondents were in the age group 25 to 34 and 58.32% of participants were females. Of 475 respondents, 44.42% and 88.42% of respondents were married and followers of orthodox Christian religion respectively. About one-third of respondents had secondary education and 30.53% of respondents were self-employed. The majority (94.32%) of respondents had a caregiver and 80.63% of patients disclosed their HIV status to at least one individual irrespective of the relationship with that person. Regarding baseline BMI, 58.11% of individuals had a normal BMI (18.5–24.99 kg/m2). Looking at the baseline and last known WHO stage, the majority, 63.37%, and 82.11% of respondents, were at their I/II WHO clinical staging respectively. Among the study participants, 58.32% of them had no OIs at baseline. Most (70.74%) of respondents had normal baseline Hgb level and more than two-thirds (70.04%) had working functional status at baseline. Regarding OIs prophylaxis at baseline, only 22.32% of respondents took IPT and about 68.00% of respondents took CPT (Table 2).

|

Table 2 Sociodemographic, Clinical, and Treatment-Related Characteristics of Respondents |

Incidence of Death

During the four years follow-up period, of the 475 respondents, 90 (18.9%) were lost to follow-up, 45 (9.5%) have died, 26 (5.5%) were transferred out to another facility, and 314 (66.1%) of respondents were still on care/active until the last censoring date. The overall mortality rate in this study, during the 846.271 total analysis time/person-years of observation, was 5.3 [95% CI: 3.4–7.1] per 100 person-years of observation.

Log Rank Test and Kaplan–Meier Survival Curve (Comparison of the Survival Probability)

From the Log rank test, there was a significant difference between age category (P=0.004), religion (p=0.028), baseline WHO stage (P<0.00), last known WHO stage (P<0.001), baseline CD4 count (p<0.001), baseline Hgb level (p<0.001), baseline OI (p=0.003), baseline functional status (p<0.001), last known adherence (p<0.001), and history of ART side effect (p=0.023). From the Kaplan–Meier survivor estimate, being 45 and above age group, being a follower of the Muslim religion, being in the baseline and the last known WHO stage III/IV, ambulatory and bedridden functional status, fair last known adherence, lower Hgb level, having OI at baseline, lower CD4 count at baseline, and having a history of ART side effect had lower survival rate/were at higher risk of death.

Proportional Hazard Assumption and Model Fitness

The p-value of the Schoenfeld residual test was insignificant (p>0.05) and there was no evidence for violation of the null-hypothesis. We also test the proportional hazard assumption by interacting with each covariate with time and the result revealed an insignificant p-value for all covariates. The model fitness was checked by plotting Nelson-Aalen cumulative hazard with Cox-Snell residual and the Cox-Snell residual is almost in line with the Nelson-Aalen cumulative hazard.

Predictors of Mortality (Cox Regression Modeling)

In the bivariable analysis variables such as educational status, residence, months on ART, having caregiver, disclosure status, baseline BMI, treatment change, baseline INH prophylaxis, and type of ART regimen had p-value >0.20 and were not eligible for the multivariable analysis. In the multivariable analysis last known/current WHO stage, baseline Hgb level, and last known/current adherence level were found to be significant predictors of mortality (p<0.05). The hazard of mortality in patients with their last known WHO stage III/IV was 15.02 [AHR = 15.02; 95% CI: 5.79–38.92] times higher as compared with respondents with their last known WHO stage I/II. Respondents who were anemic (Hgb level<12 g/L) at baseline had 2.21 [AHR = 2.21; 95% CI: 1.02–4.78] times the higher hazard of mortality as compared to their counterparts. Moreover, respondents with fair adherence level had 3.29 [AHR = 3.29; 95% CI: 1.39–7.78] times higher hazard of mortality as compared to those who had working functional status (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Multivariable Cox Regression Model for Assessing Predictors of Mortality Among HIV-Positive Adult Patients with ART |

Discussion

The mortality of HIV patients on ART is a major issue and still needs a great deal of attention. Therefore, this study was aimed to assess the incidence and predictors of mortality in HIV patients who are on ART follow-up at University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, northwest Ethiopia.

In this study, the incidence rate of mortality was 5.3 per 100 person-years of observations and this is in concordance with studies done in Somali region-Ethiopia,19 and Jimma University Specialized Hospital, southwest Ethiopia.20 Our finding was higher than the different studies done in Ethiopia.13,16,17,25,26 This may be due to the difference in the study environment in which high patient flow occurs in this setting. In turn, this results in increased mortality due to medication discontinuation and the occurrence of complications. Moreover, it was lower than a study done in Cameroon.27 This could be due to the socio-cultural difference, study time, as well as the prospective nature of a study carried out in Cameroon.

This study also identified current/last known WHO clinical stage, current/last known adherence level, and baseline Hgb level as important predictors of mortality among HIV patients who are on ART follow-up in this Hospital.

Consistent with different studies conducted in different countries,14,22,28,29 in this study, we found that patients with advanced last known WHO stage (stage III/IV) had higher hazards of death as compared with those whose last known WHO stage was I/II. This might be because infections are the leading causes of death, notably opportunistic infections such as tuberculosis is the main causes of death in HIV patients.29,30 The other plausible explanation might be, because having an advanced WHO stage indicates a patient is in an immunosuppressed state, the virus is easily multiplied with increased HIV/AIDS-related severity and the patient will end up with death.

Medication/ART drug adherence is very crucial to get the full benefit of antiretroviral drugs and in this study participants with fair adherence were at higher risk of death as compared with those who had good adherence. This is supported by previous studies conducted in Ethiopia.20–22 This might be because a low level of adherence affects the successful long-term virologic suppressibility of ART drugs and finally results in virial multiplication as well as resistance to ART drugs and increases the patient’s vulnerability for opportunistic infections and death.31

Moreover, our study at hand revealed that baseline hemoglobin level is an important predictor of mortality. Being anemic at baseline were associated with a higher hazard of mortality as compared with their counterpart. This is in line with different studies conducted across different countries and regions.9,12,19,21,22 This might be because the incidence of anemia is mostly increased with the progression of HIV disease, indicating the highest immune suppression in respondents with anemia which makes them vulnerable for OIs and finally death.32,33 The other possible explanation will be respondents with anemia might have devastating complications while taking their medications and immune suppression which all results in complications to the extent of death.

The results of this study will have critical input for policymakers and program planners in designing appropriate interventions. Besides, results obtained from this study will be helpful for health care professionals working in the ART clinic. Additionally, the study provides insights into further interventional, qualitative, as well as prospective studies.

This study had both strengths and limitations. Since it is a retrospective follow-up study it has the advantage of showing temporal relationships between independent variables and the outcome variable. But some important variables such as viral load and behavioral factors were not found in the record (due to the secondary nature of the data). The other limitation of this study was since the assessment of mortality was based on the mere record of physicians in the chart, we are not sure whether the cause of death was HIV related or not and patients who were lost from follow-up might not be traced appropriately for their current living status and this might result in underestimation of mortality. Furthermore, to estimate predictors, we have used too many covariates or parameters and this can affect the power to detect associations.

Conclusion

In this study, the incidence rate of mortality was relatively high. Being having advanced current WHO stage, fair current adherence level, and being anemic at baseline had higher hazards of death. Policymakers, as well as governmental and non-governmental organizations, should pay more attention to patients with advanced WHO stage, comorbidities such as anemia, and adherence issues to decrease the incidence of mortality.

Abbreviations

AHR, Adjusted Hazard Ratio; ART, Antiretroviral Therapy; BMI, Body Mass Index; CI, Confidence Interval; CPT, Cotrimoxazole Preventive Therapy; CHR, Crude Hazard Ratio; Hgb, Hemoglobin; HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus; IPT, Isoniazid Preventive Therapy; OIs, Opportunistic Infections; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

All result-based data are available within the manuscript and anyone can contact the corresponding author for further issues.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was conducted under the Declaration of Helsinki and ethical approval was received from the University of Gondar Institutional Review Board. Since this study was based on used secondary data from patient charts, we got a waiver for informed consent. The data collection tool did not include names and other personal identifiers to keep confidentiality.

Acknowledgment

The authors extended their special thanks to data collectors, supervisor, chart room workers, and ART data managers, for their tireless support.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

There is no funding to report.

Disclosure

The authors state they do not have competing interests.

References

1. World health organization. Global health sector strategy on HIV, 2016–2021; 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids.

2. United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. General Assembley 70 session; 2015.

3. Roth GA, Abate D, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1736–1788.

4. James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–1858.

5. AVERT. HIV and Aids in East and Southern Africa Regional Overview; 2019. Available from: https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/overview.

6. UNAIDS. UNAIDS DATA 2019. 2019.

7. Hassan RHA, Abdelaal AA, Mohammed HA, Elbashir MA, Khalid KB. Survival and mortality analysis for HIV patients in Khartoum State, Sudan 2017. World J Public Health. 2018;3(4):118.

8. MacPherson P, Moshabela M, Martinson N, Pronyk P. Mortality and loss to follow-up among HAART initiators in rural South Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103(6):588–593. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.10.001

9. Gunda DW, Nkandala I, Kilonzo SB, Kilangi BB, Mpondo BC. Prevalence and risk factors of mortality among adult HIV patients initiating ART in rural setting of HIV care and treatment services in North Western Tanzania: a retrospective cohort study. J Sex Transm Dis. 2017;2017:7075601. doi:10.1155/2017/7075601

10. Poka-Mayap V, Pefura-Yone EW, Kengne AP, Kuaban C. Mortality and its determinants among patients infected with HIV-1 on antiretroviral therapy in a referral centre in Yaounde, Cameroon: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(7):e003210. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003210

11. Rubaihayo J, Tumwesigye NM, Konde-Lule J, et al. Trends and predictors of mortality among HIV positive patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. Infect Dis Rep. 2015;7(3). doi:10.4081/idr.2015.5967.

12. Johannessen A, Naman E, Ngowi BJ, et al. Predictors of mortality in HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy in a rural hospital in Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8(1):52. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-8-52

13. Setegn T, Takele A, Gizaw T, Nigatu D, Haile D. Predictors of mortality among adult antiretroviral therapy users in southeastern Ethiopia: retrospective cohort study. AIDS Res Treat. 2015;2015:1–8. doi:10.1155/2015/148769

14. Tadege M. Time to death predictors of HIV/AIDS infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):1–6. doi:10.1186/s13104-018-3863-y

15. Tsegaye AT, Alemu W, Ayele TA. Incidence and determinants of mortality among adult HIV infected patients on second-line antiretroviral treatment in Amhara region, Ethiopia: a retrospective follow up study. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;33. doi:10.11604/pamj.2019.33.89.16626

16. Biadgilign S, Reda A, Digaffe T. Predictors of mortality among HIV infected patients taking antiretroviral treatment in Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. AIDS Res Ther. 2012;9:15. doi:10.1186/1742-6405-9-15

17. Tachbele E, Ameni G. Survival and predictors of mortality among human immunodeficiency virus patients on anti-retroviral treatment at Jinka Hospital, South Omo, Ethiopia: a six years retrospective cohort study. Epidemiol Health. 2016;38:e2016049. doi:10.4178/epih.e2016049

18. Misgina KH, Weldu MG, Gebremariam TH, et al. Predictors of mortality among adult people living with HIV/AIDS on antiretroviral therapy at Suhul Hospital, Tigrai, Northern Ethiopia: a retrospective follow-up study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2019;38(1):37. doi:10.1186/s41043-019-0194-0

19. Damtew B, Mengistie B, Alemayehu T. Survival and determinants of mortality in adult HIV/Aids patients initiating antiretroviral therapy in Somali Region, Eastern Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;22(1). doi:10.11604/pamj.2015.22.138.4352

20. Seyoum D, Degryse J-M, Kifle YG, et al. Risk factors for mortality among adult HIV/AIDS patients following antiretroviral therapy in Southwestern Ethiopia: an assessment through survival models. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(3):296. doi:10.3390/ijerph14030296

21. Kidane Tadesse FH, Hiruy N. Predictors of mortality among patients enrolled on antiretroviral therapy in Aksum hospital, northern Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(1).

22. Biset Ayalew M. Mortality and its predictors among HIV infected patients taking antiretroviral treatment in Ethiopia: a systematic review. AIDS Res Treat. 2017;2017:1–10. doi:10.1155/2017/5415298

23. Schoenfeld DA. Sample-size formula for the proportional-hazards regression model. Biometrics. 1983;39(2):499–503. doi:10.2307/2531021

24. Participant Manual. National comprehensive HIV prevention, care and treatment training for health care providers; 2018.

25. Eticha EM, Gemeda AB. Predictors of mortality among adult patients enrolled on antiretroviral therapy in Hiwotfana specialized University Hospital, Eastern Ethiopia: retrospective cohort study. J HIV Clin Sci Res. 2018;5(1):007–11.

26. Hailemariam S, Tenkolu G, Tadese H, Vata P. Determinants of survival in HIV patients: a retrospective study of Dilla University hospital HIV cohort. Int J Virol AIDS. 2016;3(2):023. doi:10.23937/2469-567X/1510023

27. Rougemont M, Stoll BE, Elia N, Ngang P. Antiretroviral treatment adherence and its determinants in Sub-Saharan Africa: a prospective study at Yaounde Central Hospital, Cameroon. AIDS Res Ther. 2009;6(1):21. doi:10.1186/1742-6405-6-21

28. Gheibi Z, Shayan Z, Joulaei H, Fararouei M, Beheshti S, Shokoohi M. Determinants of AIDS and non-AIDS related mortality among people living with HIV in Shiraz, southern Iran: a 20-year retrospective follow-up study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):1–11. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4676-x

29. Lartey M, Asante-Quashie A, Essel A, Kenu E, Ganu V, Neequaye A. Causes of death in hospitalized HIV patients in the early anti-retroviral therapy era. Ghana Med J. 2015;49(1):7–11. doi:10.4314/gmj.v49i1.2

30. Gezae KE, Abebe HT, Gebretsadik LG-E, Gebremeskel AK Predictors of accelerated mortality of Tb/Hiv Co-infected patients on art in Mekelle, Ethiopia: an 8 years retrospective follow-up study.

31. Walsh JC, Pozniak AL, Nelson MR, Mandalia S, Gazzard BG. Virologic rebound on HAART in the context of low treatment adherence is associated with a low prevalence of antiretroviral drug resistance. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(3):278–287. doi:10.1097/00126334-200207010-00003

32. Obirikorang C, Issahaku RG, Osakunor DNM, Osei-Yeboah J. Anaemia and iron homeostasis in a cohort of HIV-infected patients: a cross-sectional study in Ghana. AIDS Res Treat. 2016;2016:1–8. doi:10.1155/2016/1623094

33. Masaisa F, Gahutu JB, Mukiibi J, Delanghe J, Philippé J. Anemia in human immunodeficiency virus–infected and uninfected women in Rwanda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84(3):456–460. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0519

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.

© 2021 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution - Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License.

By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms.